Name

Bīshāpūr بیشاپور

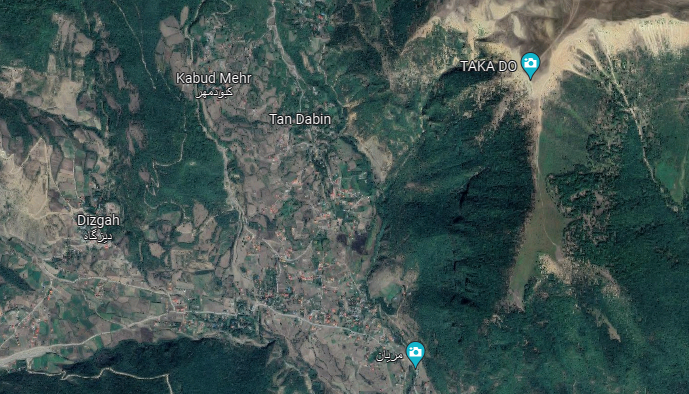

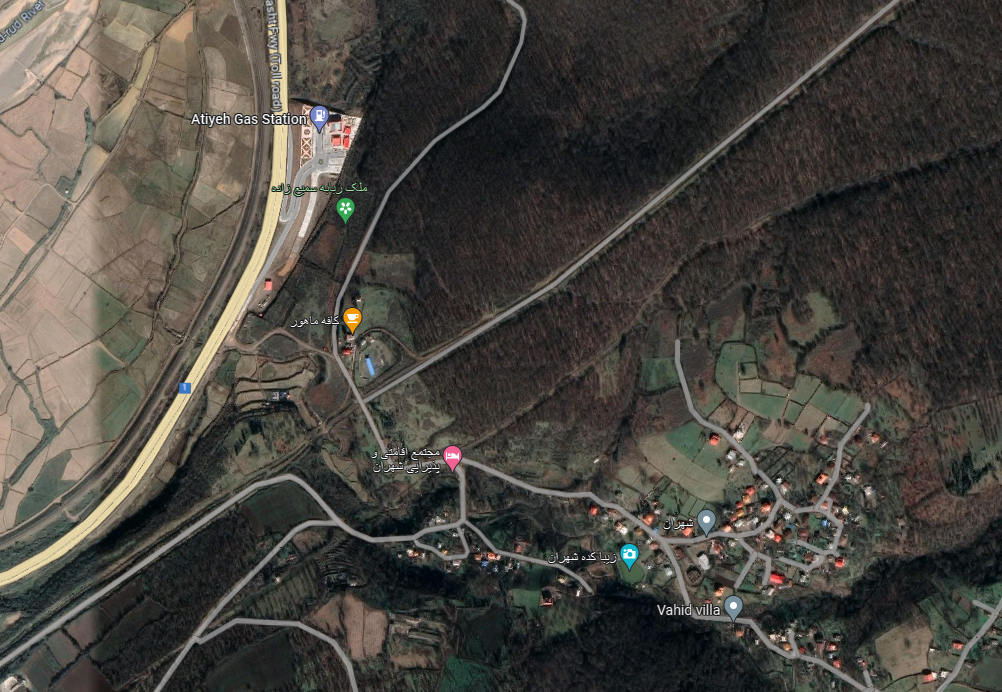

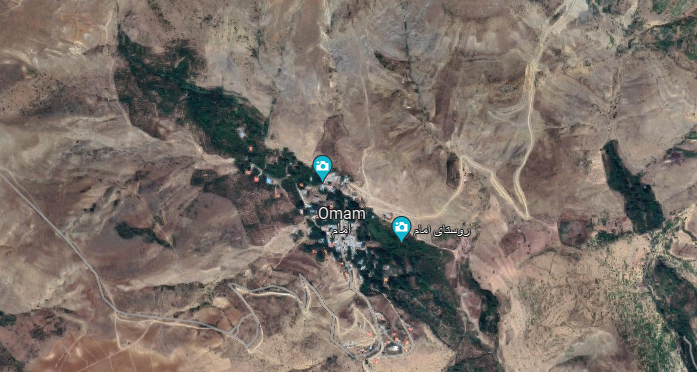

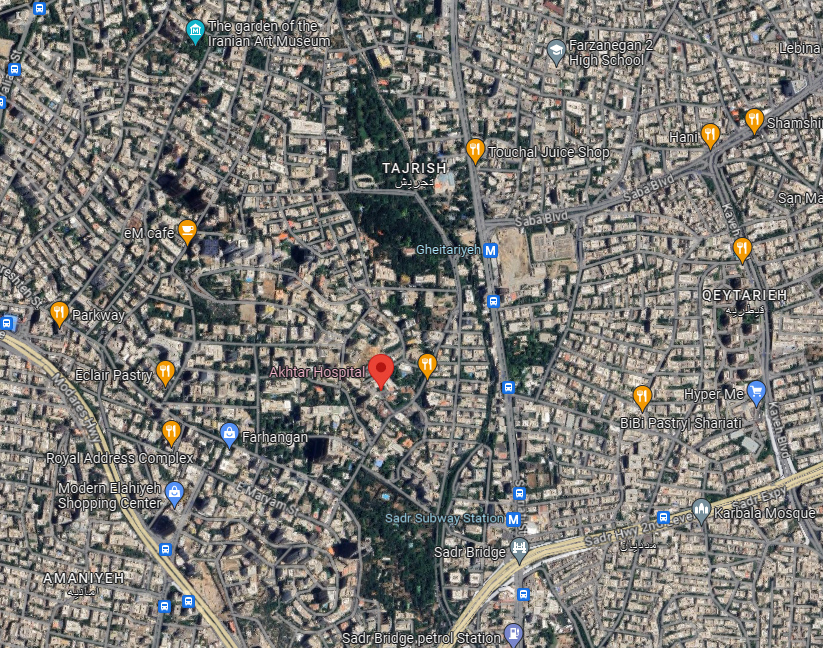

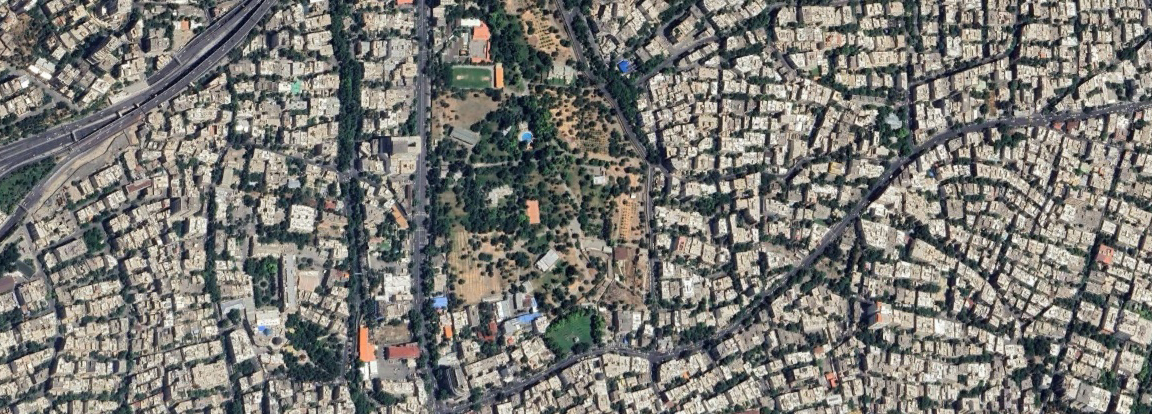

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian/Early Islamic

History and description

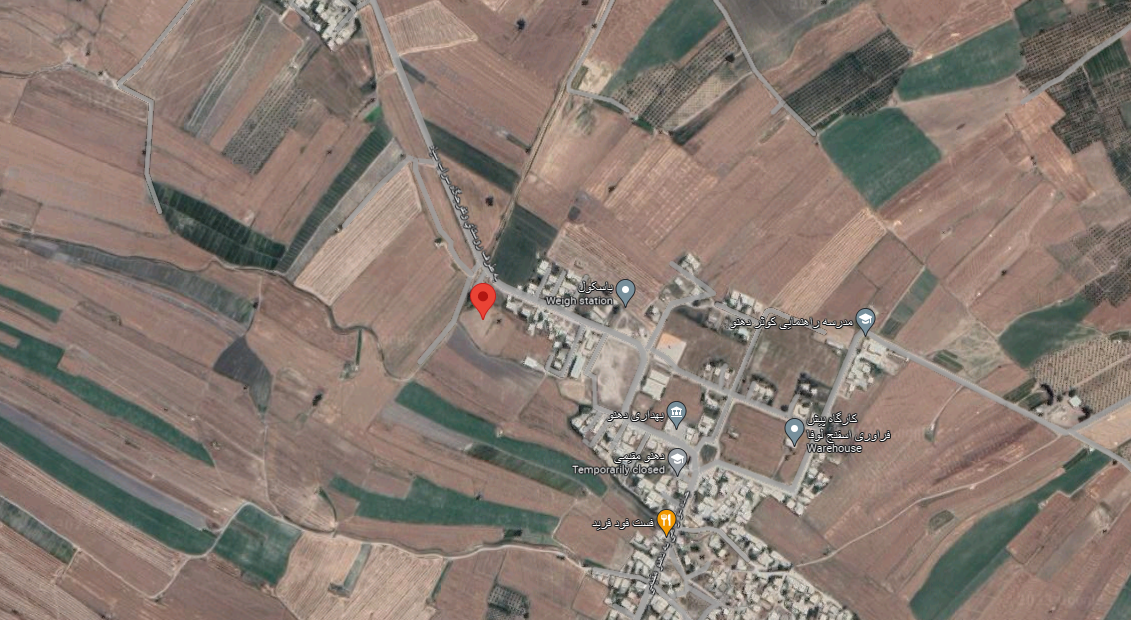

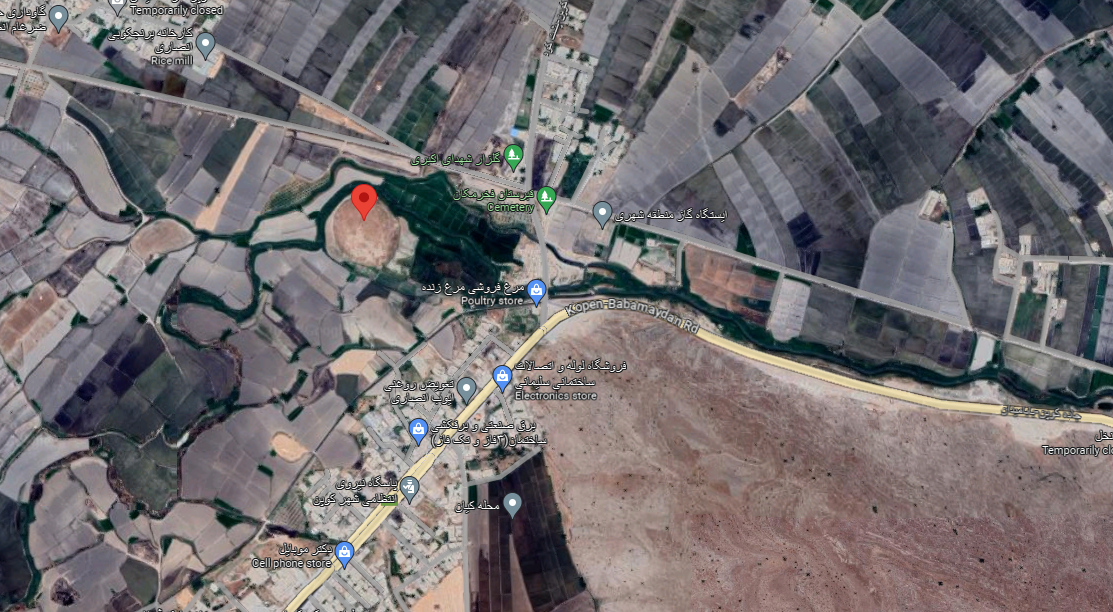

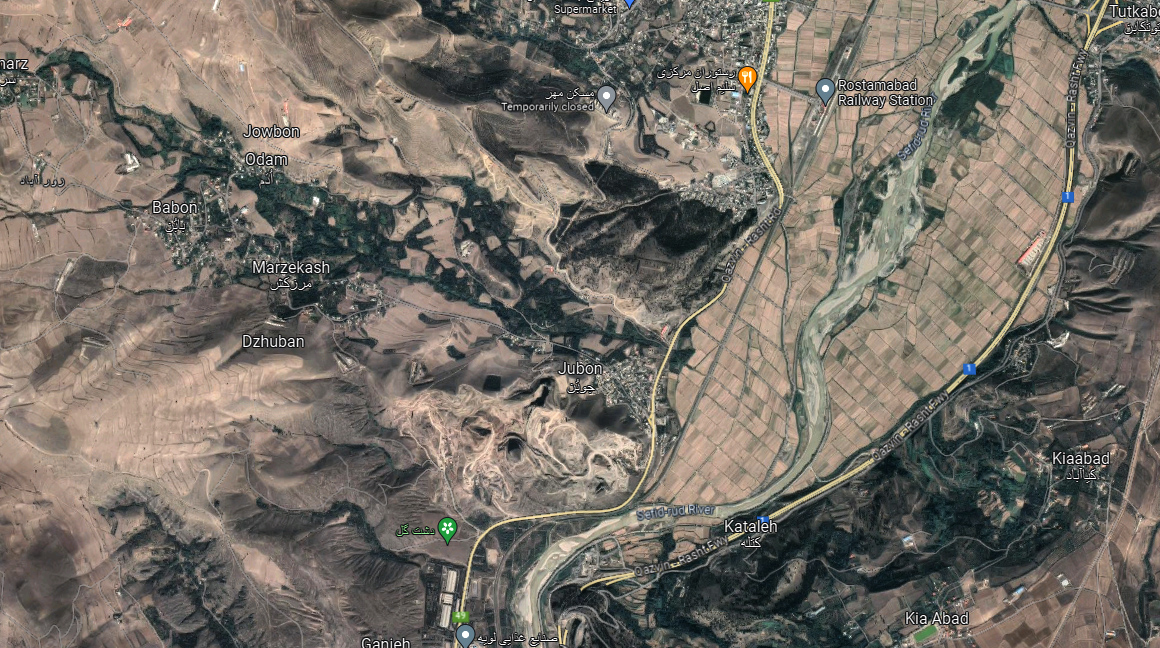

The archaeological site of Bīshāpūr lies on the left or south bank of the River Shāpūr that flows in the direction of Bushehr, protecting the city’s perimeter from the north/northwest. The site and its environs lie in the northern extremity of a valley that broadens out to the south towards Kazerun. The whole area is dotted with seasonal and perennial watercourses as well as springs such as Cheshmeyeh Sāsān in Tang-e Chowgān, Cheshme-ye pā-ye Qal’eh Dōkhtar (the Spring at the foot of Qal’eh Dōkhtar) near the eastern corner of the rectangular city fed by a subterranean canal derived from the Shāpūr River, and finally Cheshme-ye Sarāb-e Dōkhtarūn at about 3 km south of the city on the slope of Mount Shāpūr. Here where the water emerges, ruins of a square structure in stone were excavated revealing the existence of a sanctuary possibly dedicated to the Goddess of Water, Anahita. Bīshāpūr was registered on the List of the National Historic Monuments of Iran with number 339 as early as the 1950s. Bīshāpūr was inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO as a serial cultural property that includes eight Sasanian sites in Fars in 2018 (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1568).

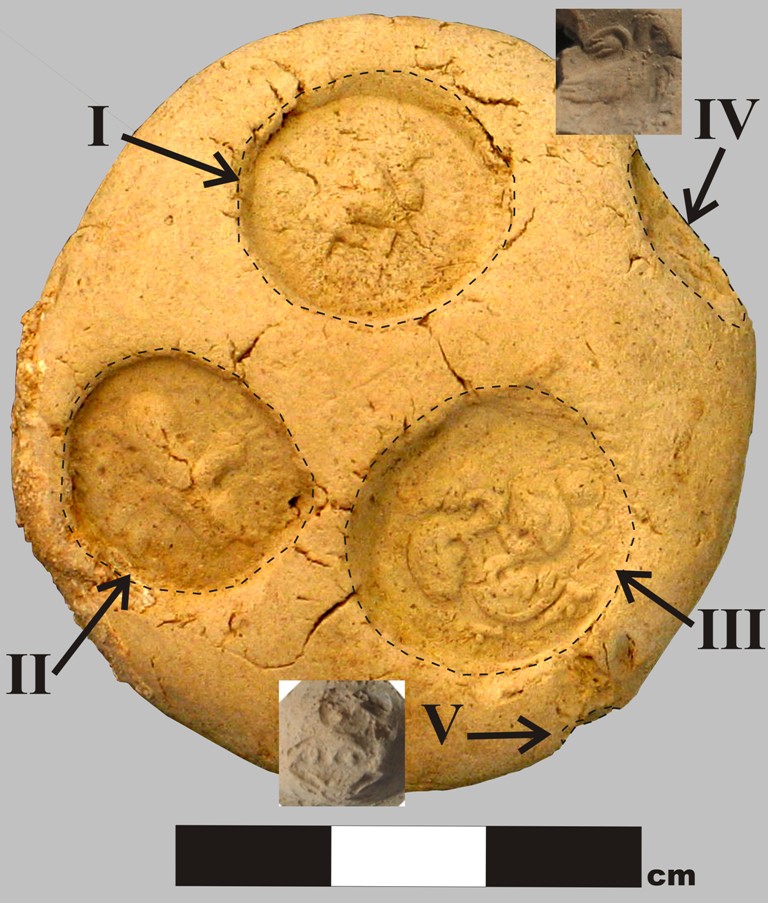

Bīshāpūr in the Sasanian period (266-640 A.D.): The original name of the site in Middle Persian is Bay Shāpūr that means Lord Shāpūr (Sundermann, “Studien zur kirchengeschichtlichen Literatur der iranischen Manichäer II,” pp. 294-295; for a full discussion of the name, see also Keall, “Bīšāpūr,”). The name figures on Sasanian coins and clay impressions (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, pp. 11-12). Roman Ghirshman gives a substantial account of the history of Bishapur in the first volume of his final excavation report (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, pp. 9-20).

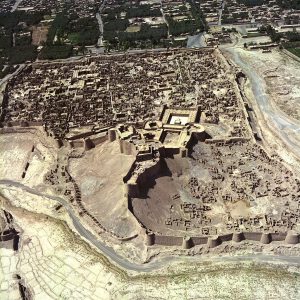

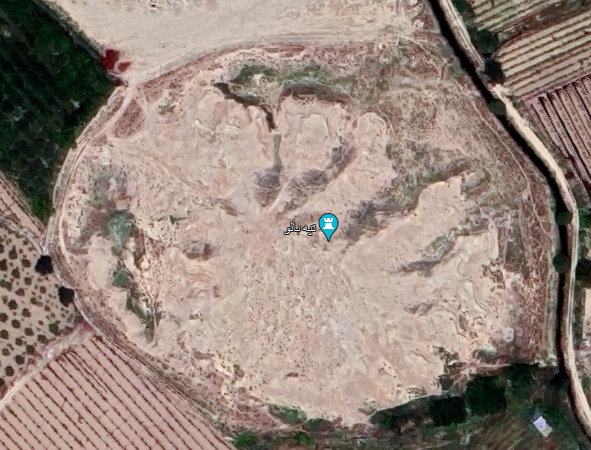

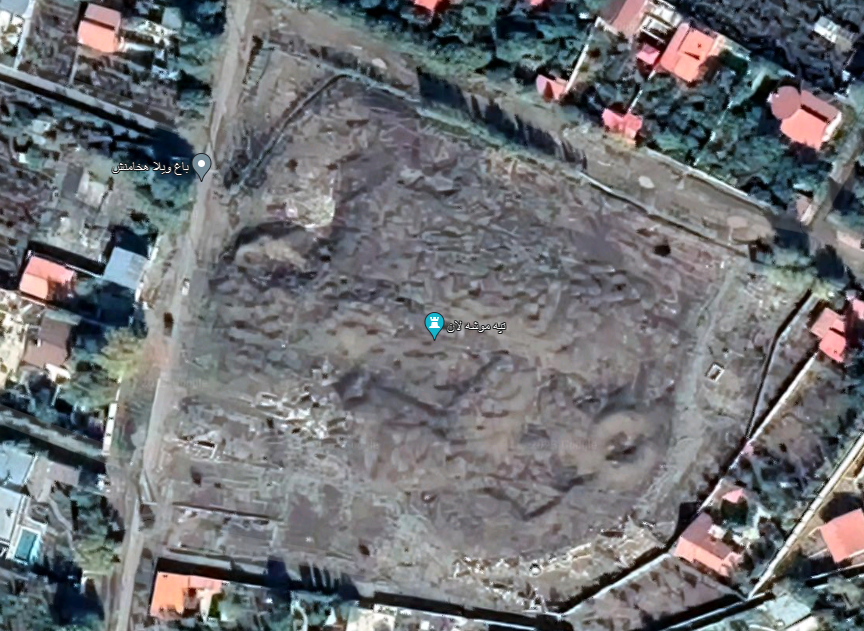

Bīshāpūr is a new foundation of Shāpūr I (240-271). After his victories over the Romans, between 244 and 263, Shapur I took a large number of prisoners who were later employed in various construction projects in Fars and Khuzestan. Unlike the round cities of Gūr and Dārāb, the layout of Bīshāpūr is Hippodamian or geometric with a system of grids, used in the Seleucid city planning (fig. 1). The rectangular divisions of the city are still visible on the surface. It seems that Sasanian Bīshāpūr was not a densely populated city as the ruined edifices and houses are scattered in the middle of gardens and flourished throughout the third and fourth centuries. The city enjoyed a prominent situation for centuries after the demise of the Sasanians as Bīshāpūr was the seat of a local governor until 502 H./1108 A.D. when Abu Sa’id Shabānkāreh, a local dynast from eastern Fars, destroyed the city and moved its population to Kāzerūn (for medieval sources, see Le Strange, The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate, pp. 262-263).

The city was probably founded late in the reign of Shāpūr I, around 266, after the third victory over the Romans (see below). Bīshāpūr is mentioned only in two sources dating from the reign of Shāpūr I: in the monumental inscription discovered in the excavation of the site and a passage from Mani’s autobiography.

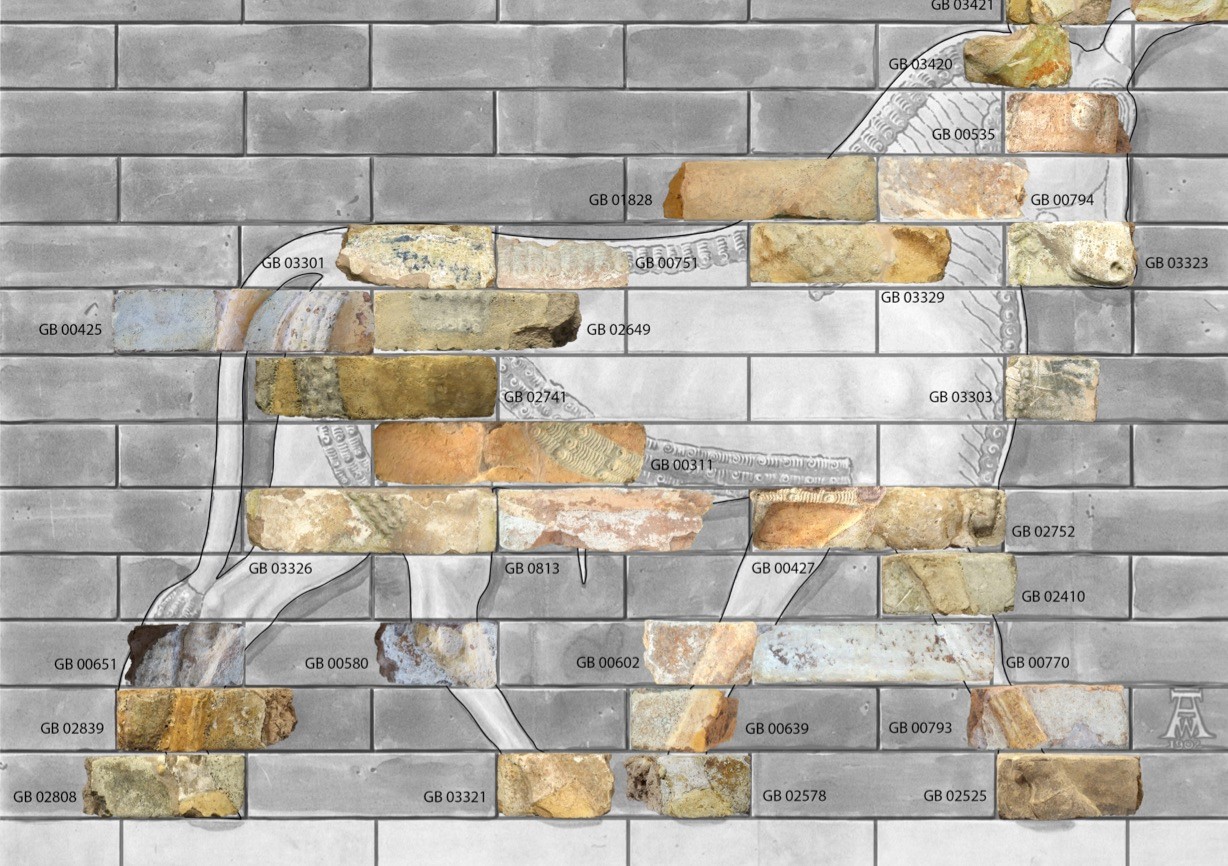

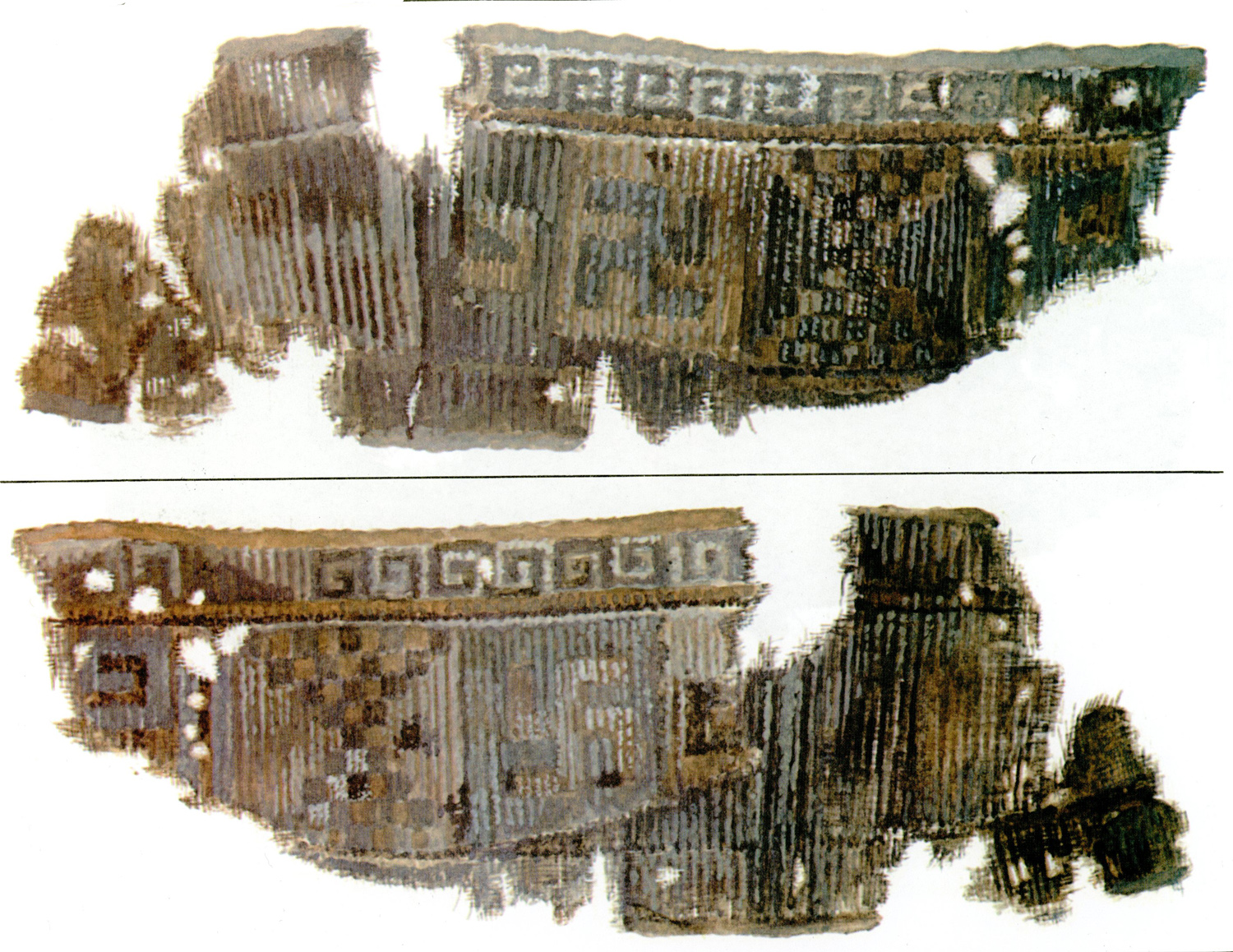

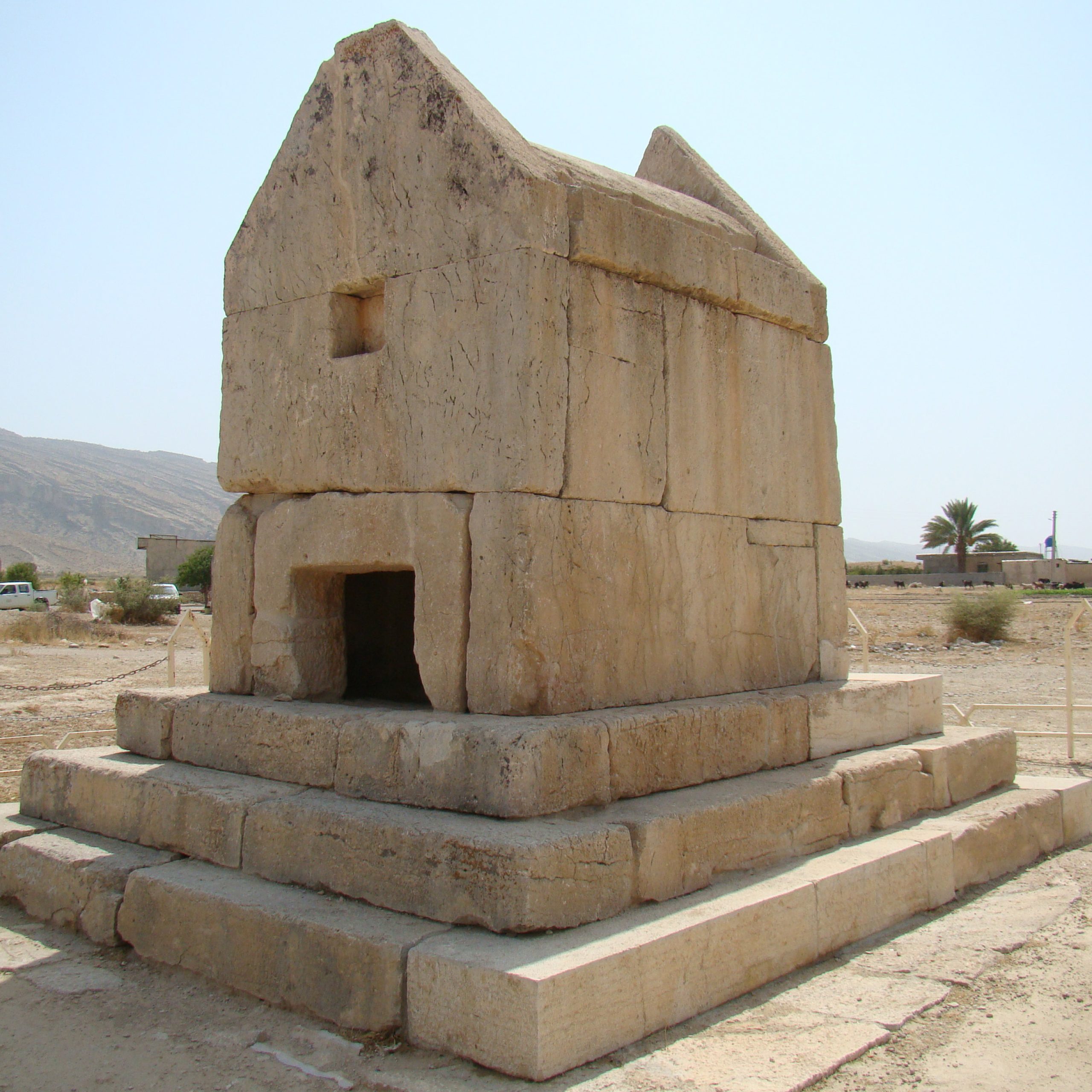

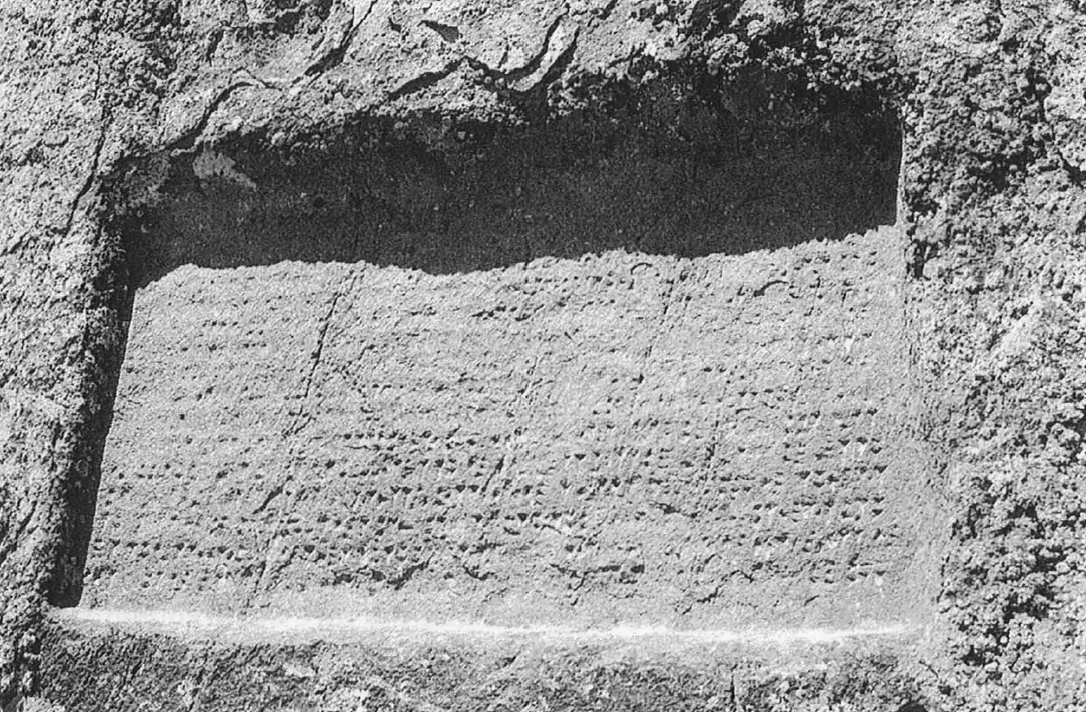

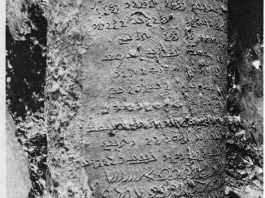

Regarding the monumental inscription (figs. 2 and 3), Ghirshman reports that the monument still had its two columns intact at the time when the city was definitively abandoned in the twelfth century (Ghirshman, “Inscription du monument de Châpour Ier,” p. 123). This corroborates the accounts of tenth-century historians such as Istakhri and Muqqadasi (see below). After the fall of the Sassanian dynasty, a new district was formed in this place, the monument was embedded in the multiple constructions which leaned against it. The inscription, 158 cm long, 87 cm wide, bears 16 lines in Sasanian Pahlavi and 12 lines in Arsacid Pahlavi (fig. 4). The inscription’s author is a certain Apasay, a native of Harrān (in Syria) and the city’s governor, who was in charge of the construction projects. The inscription mentions two columns that flanked a statue of the king, commemorating Shāpūr’s visit to his new foundation. Apasay who had raised this monument of his own money offered it to the sovereign who, satisfied, gave “gold and silver, servants, gardens, and lands.” The visit dates to the 24th year of Shāpūr I’s reign (for the full text of the inscription and discussion, see Ghirshman, “Inscription du monument de Châpour Ier,” pp. 125-126). Confronting several Sasanian and medieval sources, including Arthur Christensen’s interpretation of the inscription and medieval texts, Ghirshman dates the monument to 266 because it “allows a better understanding of the style of the monument as well as the letter N engraved on a step which is a signature of the artist who executed it. All this confirms the historical information, according to which Roman prisoners, including some weavers of textiles, were settled at Bīshāpūr, where, aside from building projects, silk and textile workshops flourished (Ghirshman, “Inscription du monument de Châpour Ier,” p. 127; Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, pp. 12-13).

The second source is a Manichaean text in Coptic found in Egypt. The text relates the biography of Mani, including a passage concerning Shāpūr I as follows: “King Shāpūr came to Persia. He arrived in the city of Beh-Shāpūr. A disease subjugated his body; he found himself in great danger. He reached the end of his life. King Shāpūr died and left this world. King Hormizd rose and was crowned in his place” (Polotzky, Manichaïsche Homilien, p. 42; the relevant passage is quoted in Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, pp. 10-11). Ghirshman thinks that the passage reveals Shāpūr I’s attachment to his city, to where he returned to spend his last days. The sequence of the bas-reliefs in Tang-e Chowgān suggests that the city’s golden age lasted, at least, until the reign of Shāpūr II to whom has been attributed the latest bas-relief (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, p. 9; Vanden Berghe, Reliefs rupestres de l’Irān ancien, pp. 88-89). The city seems to have prospered and Fars became an “ecclesiastic province” in 438 with Bīshāpūr as the seat of the province’s (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 1, p. 10), a fact that reveals the concentration of Nestorian Christians at the site; however, no trace of a Christian building has so far been discovered in excavations.

Bīshāpūr after the Sasanians (640-900 A.D.): Bīshāpūr fell into the hands of Arab conquerors in 23 or 24 H./ 643 or 644 as given by Balāzūri (Futūh al-Buldān, p. 388) and not in 16 H./637 as erroneously indicated by V. F. Bücher (“Shāpūr,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st edition, 1927), and repeated by Ghirshman (Bîchâpour, vol. 1, p. 14), and Bosworth, who copied entirely Bücher’s entry article (“Shāpūr,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, new edition, 1997). We know that the Muslim conquest of Fars did not begin before the capture of Tawwaj (south of Borāzjān) in 19 H./640 (Balāzūri, Futūh al-Buldān, pp. 386-387; Tabari, History of al-Tabari, pp. 65; for a discussion, see Hinds, “The First Arab Conquests in Fārs,” p. 214). Tabari mentions Bīshāpūr on the occasion of the resistance of Shahrak, the marzbān of Fars, against the Muslim army (Tabari, History of al-Tabari, pp. 69-70). The region witnessed a series of rebellions against the Muslim conquerors, during which cities such as Bīshāpūr and Istakhr suffered. Bīshāpūr, however, seems to be still inhabited in the tenth century. Both Istakhri and Muqqadasi have left comprehensive accounts of the city and its ruins (for a comprehensive survey of medieval sources, see Schwarz, Iran im Mittelalter, pp. 30-33). Istakhri writes that King Shāpūr founded Bīshāpūr and that the city was as large as Istakhr, but it was in better shape and showed more prosperity. For the construction of the houses, one uses the same material as in Istakhr, also here as there, there is unhealthy air, whereas outside the city the air is healthy. The city has a wall and no suburb. Istakhri mentions two fire temples, which were among the most respected and especially revered fire temples of Fars, one at the Shāpūr gate and the other at the Sasan gate (Istakhri, Masālik va Mamālik, p. 110). Other medieval sources such as Ibn Balkhi’s Fārsnama or those recounted in Fārsnāme-ye Nāseri and Āsār-e Ajam attribute the foundation of the city to Tahmures, a mythical king of Persia, its destruction to Alexander, and its rebuilding to Shāpūr, son of Ardashir (The Farsnama of Ibnu’l-Balkhi, p. 142). In the fourteenth century, Hamdōllah Mostowfi, who frequently copies Ibn Balkhi’s Fārsnama, calls it Bishāvūr as he writes (The Geographical Part of the Nuzhat-al-Qulūb, p. 126):

It was founded by Ṭahmūrath the Demon-binder and named Dindilā... Alexander the Great, when he conquered Fars, laid it in ruins, and king Shāpur I rebuilt it all anew, calling it Bishāpur after his own name; but originally this was Band-i-Shāpur (Sapor's building), which in the lapse of time and by the coalescing of the letters became Bishāvūr. The climate is hot; for to the north the city is shut in, by which cause too it is damp. Its water is from the great river which has taken its name from the town. The crops grown here are corn, rice, dates, oranges, shaddocks, lemons, with all other kinds of good fruits of the hot region, which same sell here for a small price; so that those coming and going are perpetually eating of the same. Various sweet-smelling flowers too abound, such as water-lilies, violets, jasmine and narcissus; and silk too is produced. The people are of the Shafi'ite sect. Some distance outside Bishāvur there is seen the statue of a man in black stone, standing in a temple, and above life size. Some say it is a talisman, others assert that this was once a living man whom God Most High turned to stone. The kings in those parts hold it in much honour and veneration, making visitations to the same, and anointing it with unguents.

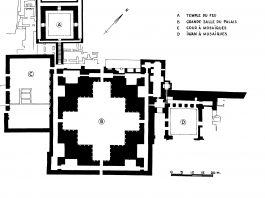

The ruins: The royal city with its perimeter of some 5 km covers an area of 230 hectares and was protected on the north side by a fortress on the slope of the mountain, at the entrance of a gorge known as Tang-e Chowgān. A massive wall with its semi-circular towers 10 m wide protected the city on all sides. Sasanian Bīshāpūr consisted of a number of prominent buildings in the northern sector of the city. The description follows Ghirshman’s nomenclature of the buildings as marked in his final reports and plans (fig. 5).

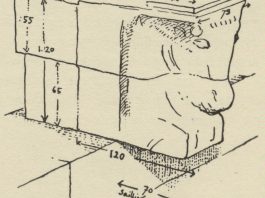

Building A: The square, semi-subterranean structure that had initially been interpreted as a fire temple is now considered a temple of Anahita, goddess of water. The masonry is a combination of Sasanian and Roman methods of construction; the inner wall is in rubble masonry and mortar while the outer one is in finely dressed blocks of stones put together without mortar. A vaulted stairway of 25 steps leads to a square 14-meter courtyard paved with stones (figs. 6 and 7). The courtyard lies 14 m below the surrounding area (fig. 8). The northwest wall that is preserved to a height of 14 m has preserved parts of its protruding sculptures (figs. 9 and 10). Here are fragments of two protruding sculptures in the shape of kneeling bulls imitating Achaemenid column capitals (fig. 11). Ghirshman found two other similar sculptures in the rubble at the foot of the southeast wall. Ghirshman thought that these four projecting sculptures, which were opposite each other two by two, had probably served as support for the beams of the roof. Based on the presence of a layer of ash that covered the excavated material inside the room, Ghirshman thought that the roof was made of wooden beams (Ghirshman and Salles, “Chapour: rapport préliminaire de la première campagne de fouilles,” p. 119). On each side of this courtyard, which may have been a roofed sanctuary, is an entrance to interior vaulted corridors equipped with water channels (fig. 12). The building was known as an Atashkadeh as early as the 19th century (Ouseley, Travels, vol. 1, p. 280). Ghirshman who partially explored the building insisted that it was a fire temple (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 2, p. 11). However, later excavations led by A. Sarfaraz showed that the building with its associated water channels and the central pool was an unroofed temple of Anahita (Sarfaraz, Chaychi Amirkhiz, and Sa'idi, Shahr-e Bāstāni-ye Bīshāpūr, pp. 234-247; see counter-arguments by Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, p. 150). The building displays the plan of a square sanctuary and ambulatory known in the Parthian period from sites such as Hatra and Nisa. The circulation and division of water were regulated through perforated stone filters placed at intervals. The channels provided water for a large pool (11 x 10 m) in the courtyard thus completing the cycle of the sacred water (fig. 13).

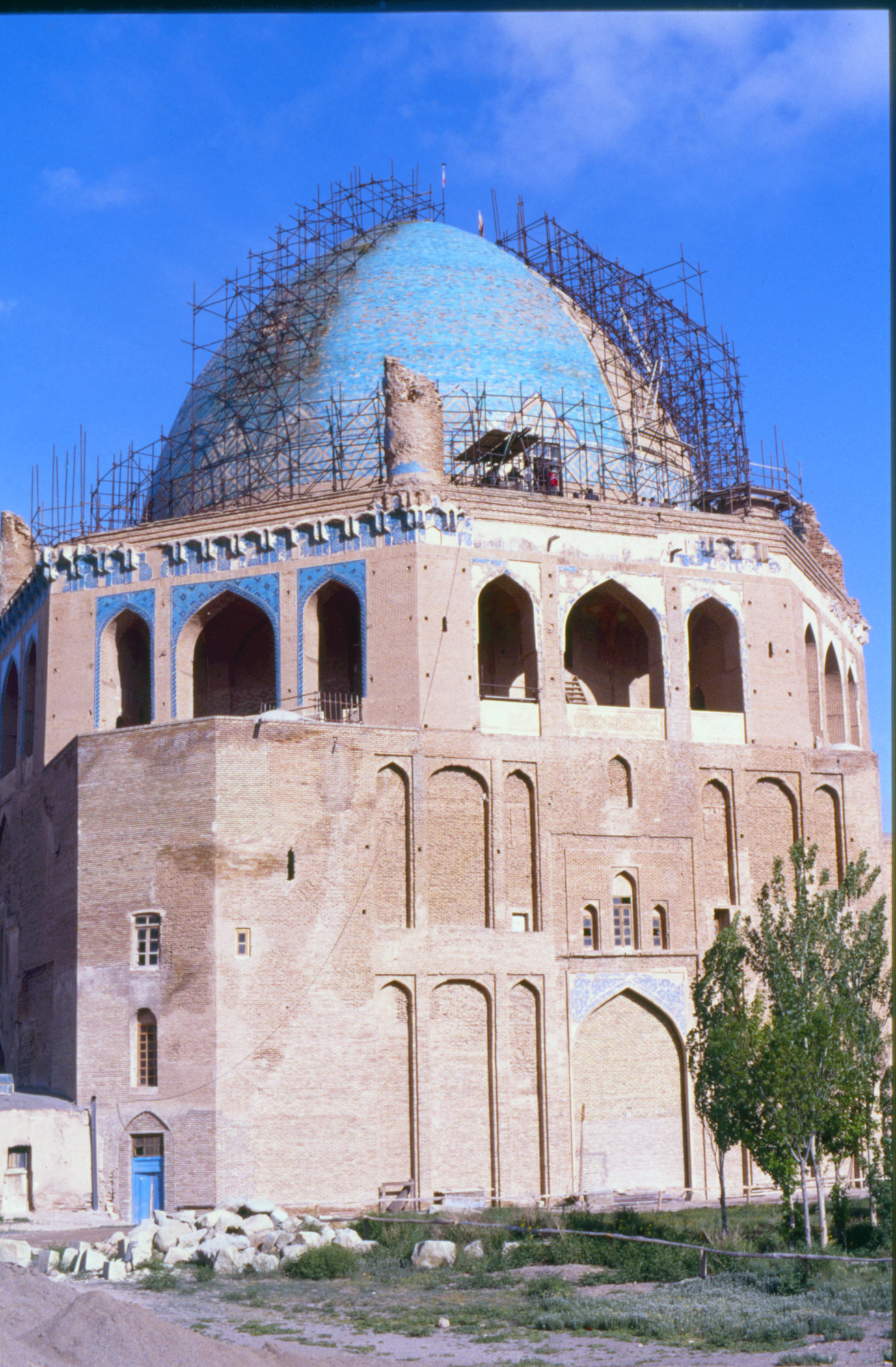

Building B: A cruciform building of 800 square meters is the largest Sasanian building at the site and amongst the largest domed halls of pre-Islamic Iran (fig. 14). The entire building was made of rubble masonry. The hall is a square building, 22 x 22 m, flanked on either side by four eyvān (iwān) 9 x 7 m, displaying a typical Sasanian building with a four-eyvān plan or chāhār-taq. Ghirshman proposed a technically improbable cupola 25 m high for the building as he wrote (Ghirshman, Bîchâpour, vol. 2, p. 20):

La salle centrale du triple iwan, large de près de 15 mètres, ne pouvait être couverte ni à l’aide de cintres, ni à l’aide d’arcs armés de roseaux. De fait, son mur Sud-Ouest, le mieux conservé, montre clairement par son mouvement vers l’intérieur qu’il passait sans transition visible à la voûte semi-elliptique ou parabolique par un avancement vers l’intérieur de la salle de chaque nouvelle rangée de pierres superposées.

The interior of the cruciform hall was decorated with wall paintings and sixty-four stucco ornamented niches. The edges of the eyvāns had been covered with mosaics combining Iranian and Roman motifs. The mosaic bands were later covered with plaster, probably in the Islamic period. According to Ghirshman (Bîchâpour, vol. 2, p. 11) and Sarfaraz (Shahr-e Bāstāni-ye Bīshāpūr, pp. 207-209 ), this domed hall was a palace or an audience hall while Huff thinks that it was an elaborate type of Ardashir’s fire temple at Firuzābād. Huff makes a detailed analogy between the monument known as Takht Neshin at Firuzabad and the large, cruciform hall at Bīshāpūr. There is a surprising similarity between the closed interior floor plans of Takht-e Neshin and the cruciform hall at Bīshāpūr surrounded by corridors that are designed differently and partially expanded to rooms. He convincingly argues that the cruciform hall at Bīshāpūr was a sanctuary or fire temple (Huff, “Der Takht-i Nishin in Firuzabad,” pp. 530-532; “Architecture sassanide,” p. 54). Adjacent to the cruciform hall is a domed subterranean chāhār-tāq, the relation of which with the rest of the complex is not clear.

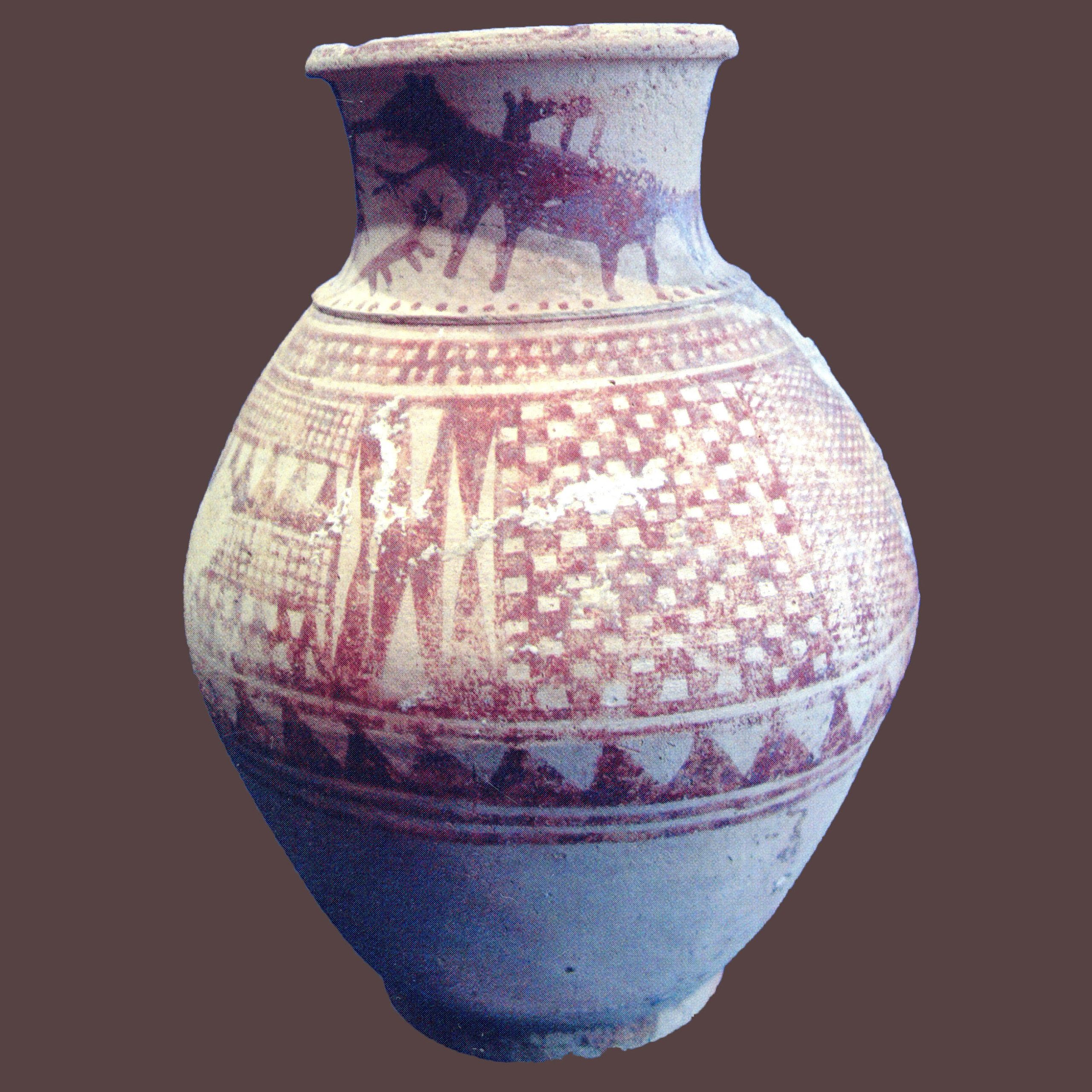

Building C: A large rectangular building (34 x 40 m) on the northwest side of the cruciform hall is known as the Hall of Mosaics (the Cour à mosaiques in Ghirshman's plan) where nine fragmentary mosaic panels were discovered. Sarfaraz’s further excavations revealed that the walls of the Hall were decorated with niches covered with painted stuccos similar to those in the cruciform hall. According to Ghirshman who excavated the building, the Hall changed in the late Sasanian/early Islamic period. Architectural finds and numismatic evidence substantiate the reoccupation of this building in the late seventh and early eighth centuries. Ghirshman attests that some of the discovered stuccos resemble those from Samara.

Building D: A building with triple eyvān was excavated in the southeastern sector of the cruciform hall (fig. 15). The excavation of the square central hall of this eyvān revealed eighteen mosaic panels that once decorated the edges of its walls. It is unclear whether the entire floor was covered with mosaics (figs. 16).

The commemorative columns: Two commemorative columns were erected on the east-west axis of the city, close to the eastern gate of the city (figs. 2, 3, 4). Ghirshman’s excavations revealed that the columns were at the center of a stone platform of ashlar masonry, 6.50 x 3.20 m. The columns, 6.5 m high, are placed 75 cm apart. One of the columns bears a Middle Persian inscription in the name of a certain scribe named Apsāy, commemorating the erection of the king’s statue in 266.

The mosque: The ruins of a small mosque (12 x 12 m) with a peristyle courtyard and four eyvāns were explored in the middle of the site (fig. 17). The building seems to be an important mosque with inscribed column bases, bearing Koranic texts, and stuccos. Sarfaraz proposes a mid-tenth century date (Shahr-e Bāstāni-ye Bīshāpūr, p. 306).

The Governor’s Residence: The ruins of a large, rectangular building, 250 x 150 m, stand in the southern sector of the city, the excavation of which by Mohammad Mehryar showed that it was an important building, possibly the governor’s residence or palace, which underwent subsequent changes and alteration to become a mosque.

Archaeological Exploration

The majority of European travelers who visited the site were attracted by the rock-reliefs in the Tang-e Chowgan. With the exception of Ouseley, Flandin and Coste, none has described the ruins (for example, see Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 2, pp. 206-220). David Talbot Rice and Gerald Reitlinger carried out the first thorough archaeological survey of the site in 1931 (Rice, “The City of Shāpūr,”). Roman Ghirshman and Georges Salles conducted five seasons of excavations at Bīshāpūr intermittently between 1935 and 1941 on behalf of the Louvre Museum. Ghirshman focused on Sasanian remains and uncovered the most prominent architectural vestiges such as the Great cruciform building, the mosaic halls, and part of the adjacent subterranean temple, in the northern sector of the site. Aside from preliminary reports (for a complete list, see Vanden Berghe, Bibliographie analytique, pp. 74-75), Ghirshman’s final reports are published in 1956 and 1971 (see bibliography). Ali Akbar Sarfaraz carried out excavations for ten seasons between 1968 and 1978, first on behalf of the Archaeological Department of the Ministry of Culture and Arts and later on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research (see bibliography). He completed the excavation of the subterranean temple and the building named Valerian’s Palace, uncovered sections of the royal city’s wall, and discovered a new Sasanian relief in Tang-e Chowagān. The excavations resumed later under Mohammad Mehryar on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research from 1995 to 2004. Mehryar explored the southern sector of the town occupied during the early Islamic period, the partial report of which was published in 1999 (see bibliography).

Finds

Stone architecture with ashlar masonry; rubble masonry; inscribed structures such as commemorative columns; mosaics with human figures; stucco panels; sculptures; coins; wall paintings. Early Islamic plain and decorated ceramics.

Bibliography

Balāzūri, A. ib. Y., Futūh al-Buldān. Liber expugnationis regionum, ed. M. J. de Goeje, Leiden 1866.

Bosworth, C. E., “Shāpūr,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edition, 1997.

Bücher, V.F., “Shāpūr,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st edition, 1927.

Curzon, G. N., Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 2, London, 1892.

Fasāi, Mirza Hasan., Fārsnāme-ye Nāseri, vol. 2, reprint 1367/1998, pp.

Flandin, E. and P. Coste, Voyage en Perse, vol. 1, Paris, 1843-54.

Ghirshman, R. and G. Salles, "Rapport préliminaire de la première campagne de fouilles (Automne 1935 -Printemps 1936)," Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 10, No. 3, 1936, pp. 117-122.

Ghirshman, R., “Inscription du monument de Châpour Ier à Châpour,” Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 10, No. 3, 1936, pp. 123-129, pl. XLIV.

Ghirshman, R., “Les fouilles de Châpour, Iran (deuxième campagne, décembre 1936 – avril 1937),” Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 12, No. 1, 1938, pp. 12-19, pl. IX-XIV.

Ghirshman, R., Bîchâpour, vol. 1, Paris, 1971.

Ghirshman, R., Bîchâpour, vol. 2, Paris, 1956.

Hinds, M., “The First Arab Conquests in Fārs,” Iran, vol. 22, 1984, pp. 39-53.

Huff, D., “Der Takht-i Nishin in Firuzabad,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1972, pp. 517-540.

Huff, D., “Architecture sassanide,” Splendeur des Sassanides, exhibition catalogue, Bruxelles, 1993, pp. 45-61.

Ibn Balkhi, The Farsnama of Ibnu’l-Balkhi, edited by G. Le Strange and Le Strange, G. and R. A. Nicholson, E. J. W. Gibb Memorial, New Series 1, Cambridge, 1921.

Istakhri, M., Masālik va Mamālik, edited by I. Afshar, Tehran, 1340/1961.

Keall, E., “Bīšāpūr,” Encyclopedia Iranica, vol. IV, Fasc. 3, 1989, pp. 287-289.

Mehryar, M., “Pishine-ye pajūheshhā va kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenāsi dar Bishapūr,” Proceedings of the Second Congress of the History of Iranian Architecture and Urbanism, Bam, Kerman, April 14-18, 1999, vol. 2, Tehran, 1378/1999, pp. 11-71.

Mehryar, M., “Simā-ye shahr-e Bīshāpūr dar dowrān-e eslāmi,” Proceedings of the Second Congress of the History of Iranian Architecture and Urbanism, Bam, Kerman, April 14-18, 1999, vol. 3, Tehran, 1378 / 1999, pp. 11-138.

Mostowfi, Hamdōllah, The Geographical Part of Nuzhat-al-Qulūb composed by Hamd-Allah Mustawfi of Qazwin in 740 (1340), translated end edited by G. Le Strange, E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Series, vol. XXIII.2, London, 1919.

Ouseley, W., Travels, vol. 1, London, 1891.

Rice, D. T., “The City of Shāpūr,” Ars Islamica, vol. 2, 1935, pp. 174-188.

Sarfaraz, A., “Bīshāpūr. Shahr-e bozorg-e sāsāni,” Bāstānchenāsi va Honar-e Iran, vol. 2, 1348/1969, pp. 69-74.

Sarfaraz, A., “Bīshāpūr,” Excavation Report, Iran, vol. 8, 1970, p. 178.

Sarfaraz, A., A. Chaychi Amirkhiz, M. Sai’di, Shahr-e Bāstāni-ye Bīshāpūr, Tehran, 1393/2014.

Salles, G., and R. Ghirshman, “Chapour: rapport préliminaire de la première campagne de fouilles (automne 1935- printemps 1936),” Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 117-122, pls. XXXIX-XLIII.

Salles, G., “Nouvelles documents sur les fouilles de Châpour,” Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 13, Nos. 3-4, 1942, pp. 93-100.

Von Gall, H., “Die Mosaiken von Bishapur,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 4, 1971, pp. 193-205, pls. 31-35.

Schippmann, K., Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, Berlin, 1971, pp. 142-153.

Sundermann, W., “Studien zur kirchengeschichtlichen Literatur der iranischen Manichäer II,” Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 13/2, 1986, pp. 239-317.

Tabari, M., History of al-Tabari, translated by C. E. Bosworth, New York, 1999.

Vanden Berghe, L., Bibliographie analytique de l’archéologie de l’Iran ancien, Leiden, 1979.

DOWNLOAD AS PDF

DOWNLOAD AS PDF