Firuzabad/Qal’eh Dōkhtarفیروزاباد/قلعه دختر

Location: Qal’eh Dōkhtar is a Sasanian castle in central Fars, southern Iran, Fars Province.

28°55’15.0″N 52°31’48.0″E

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian

History and descripton

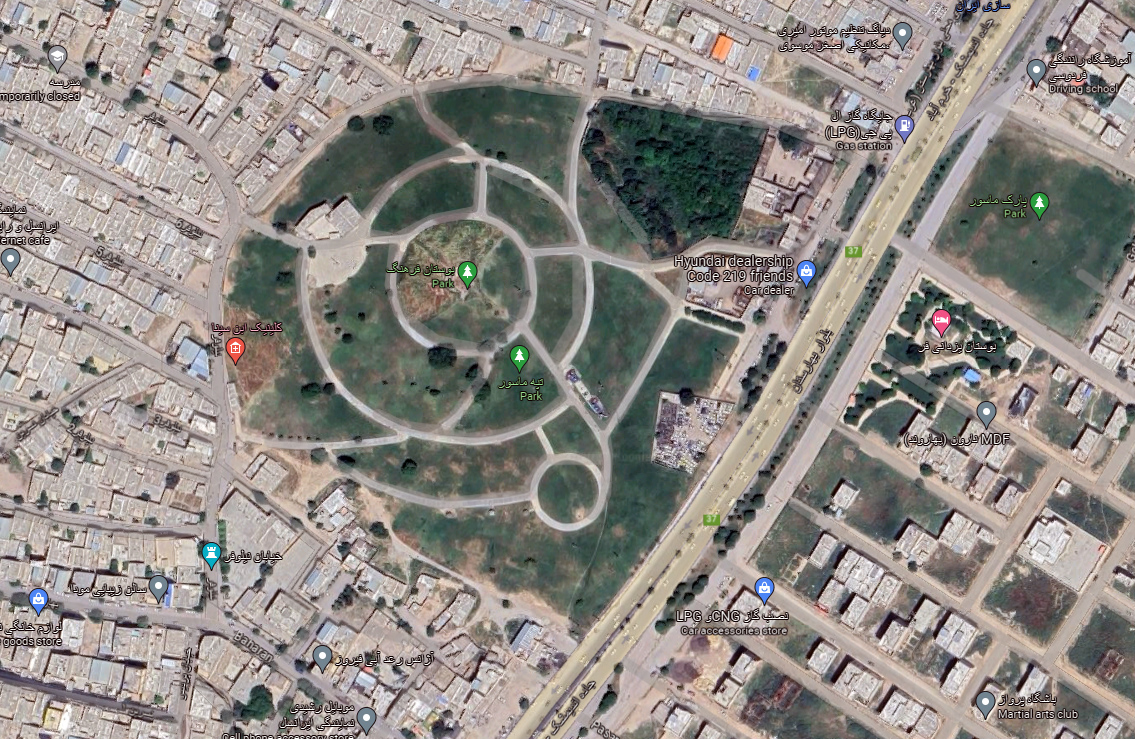

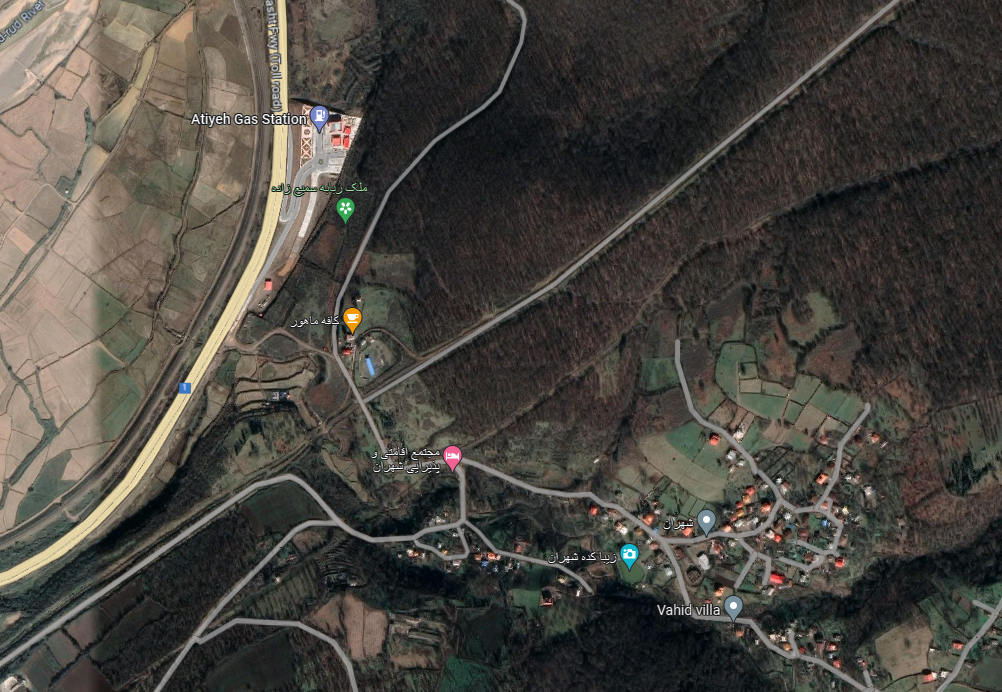

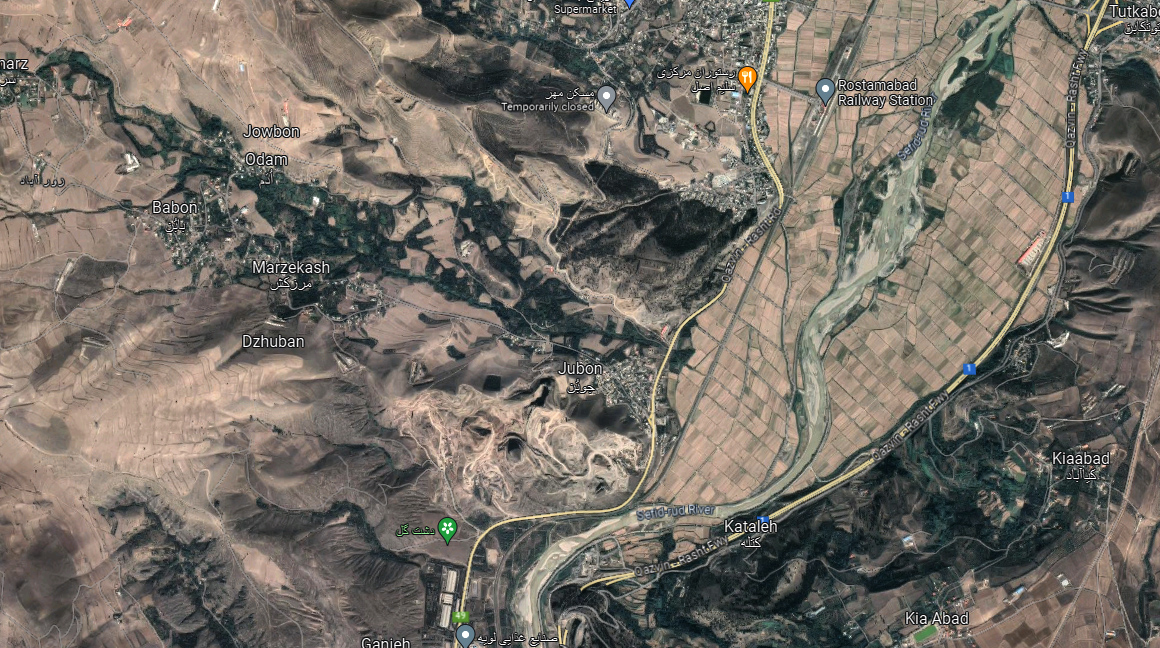

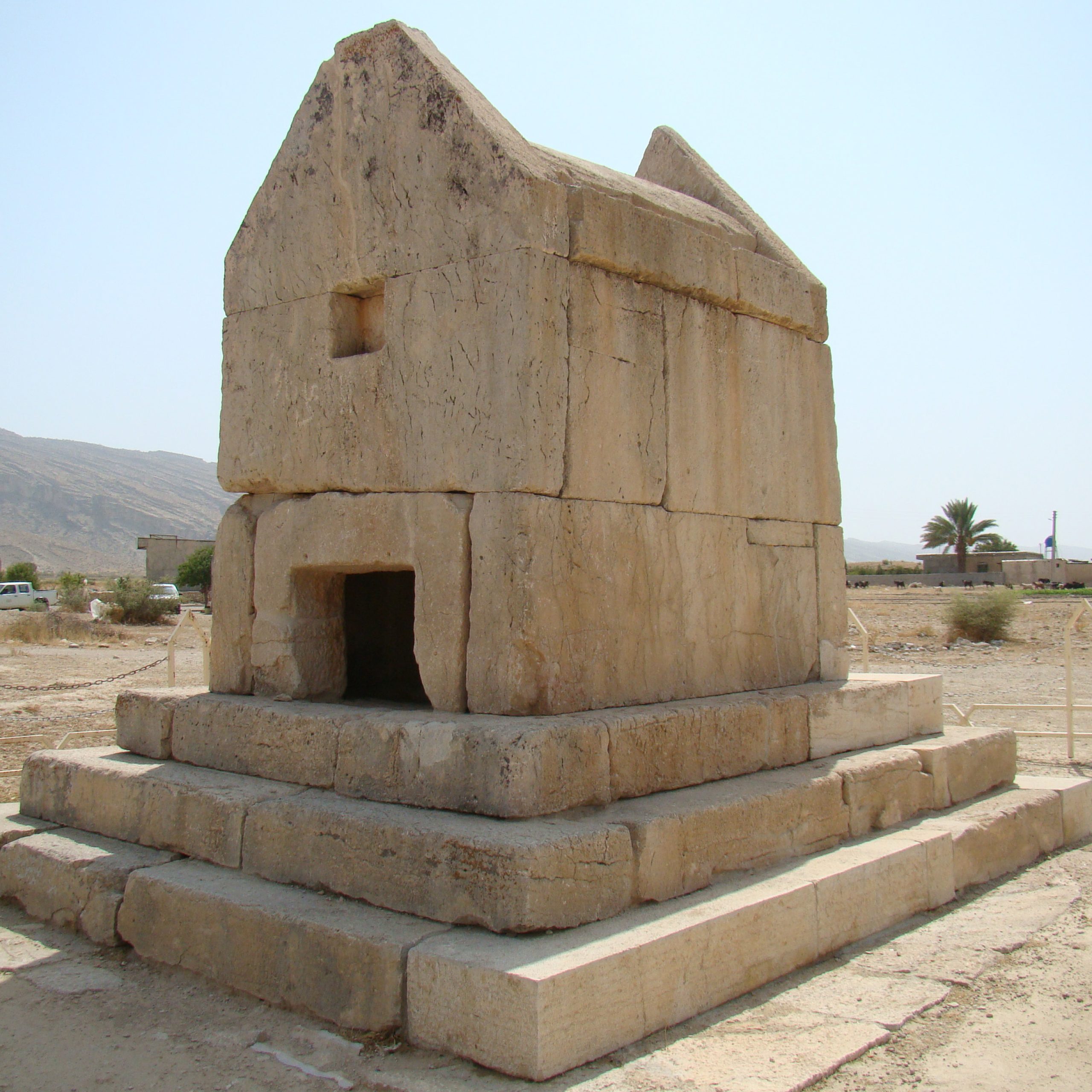

Located to the north of the Firuzabad plain, the Tangāb gorge, alongside its eponymous river, serves as the sole conduit connecting central Fars to the southern plains of the province. Within proximity of each other in the gorge, there are several significant monuments from the early Sasanian era. Traveling from the north, there is the watchtower known as Naqarreh-Khanneh, followed by the renowned Qal’eh Dōkhtar, a formidable fortress that commands the valley and its environs. Furthermore, a kilometer to the south, there is a rock relief depicting the investiture of Ardashir I on the right bank of the river, and remains of a stone bridge, constructed on the orders of the early Sasanian minister, Mehr Narseh, according to a nearby inscription. Finally, at another kilometer to the south, there is the largest and most dramatic Sasanian rock-relief with an 18-meter panel featuring the horse battle between Ardashir and Sasanian knights against Artabanus V and his cavalry.

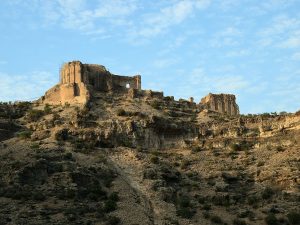

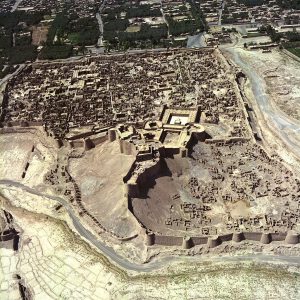

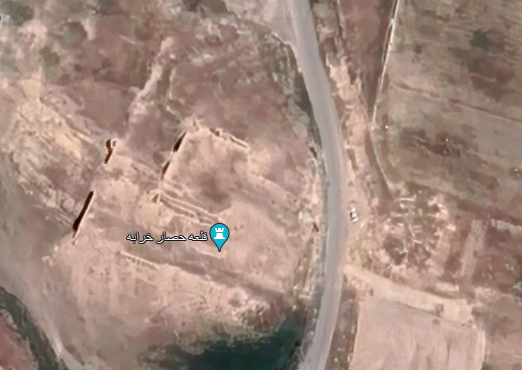

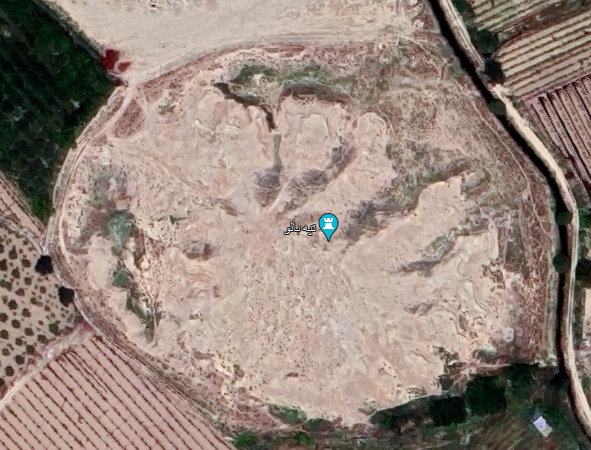

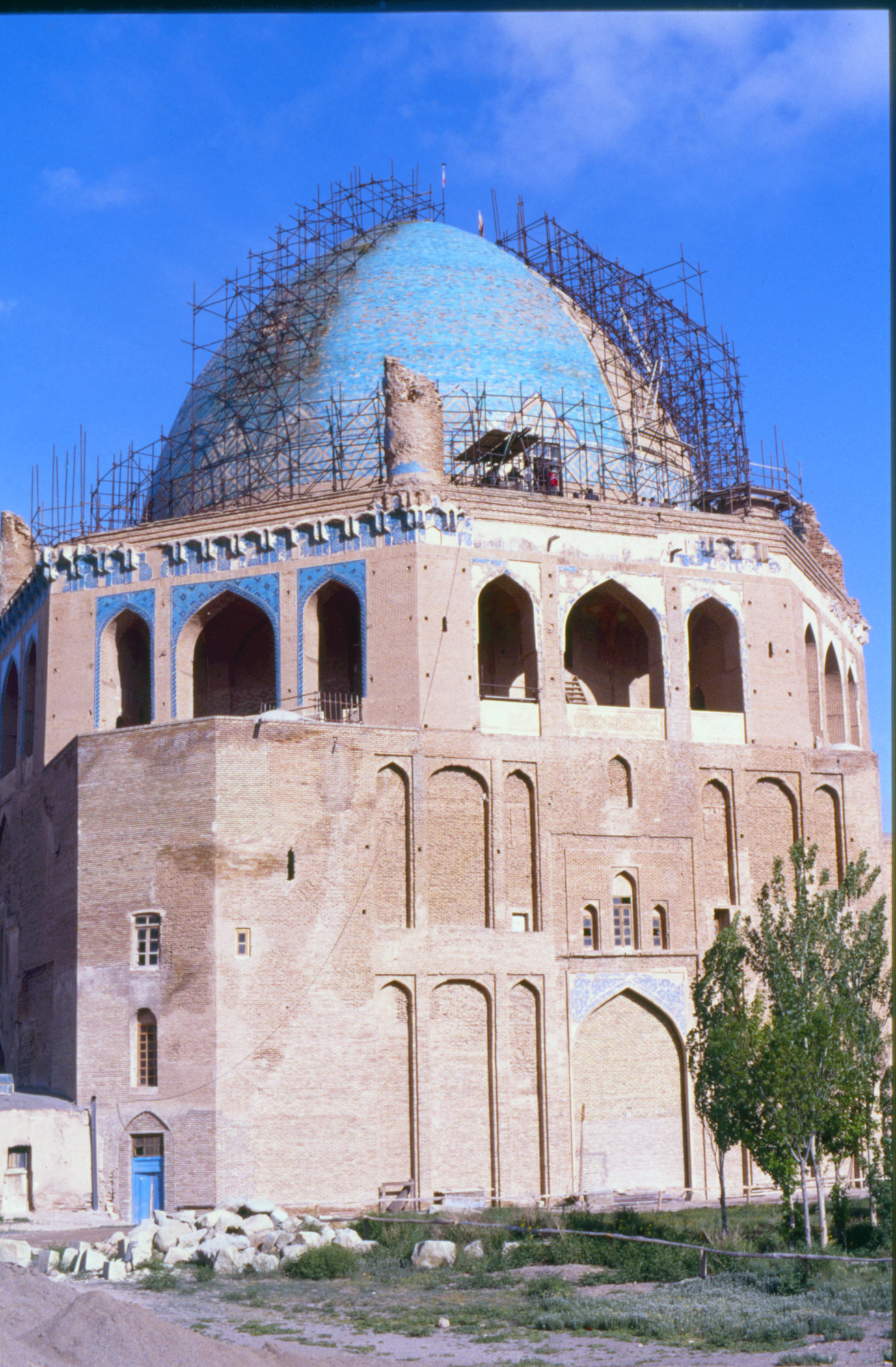

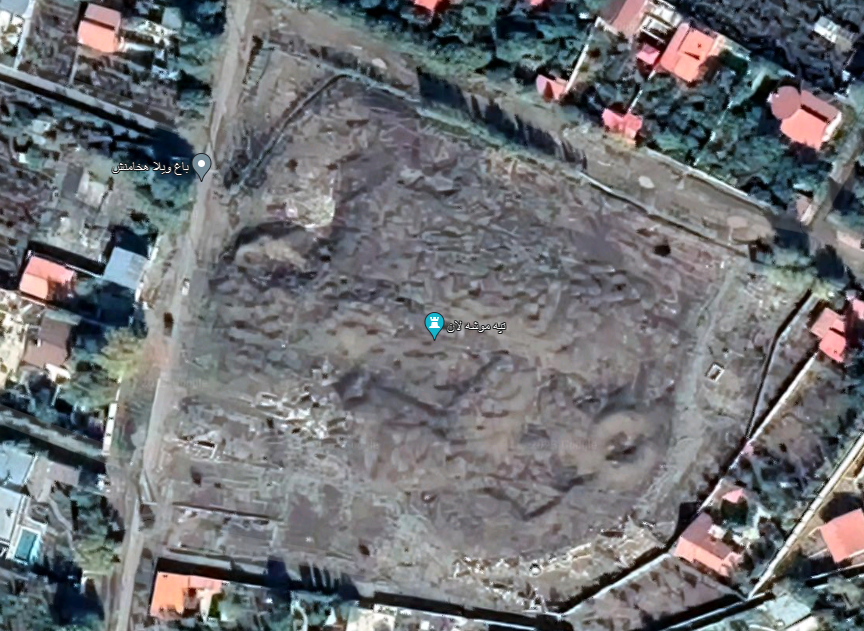

Qal’eh Dōkhtar (fig. 1) is an expansive stronghold that houses a palace constructed by Ardashir I before his pivotal triumph over the final Parthian monarch in the year 224 A.D. The castle is perched on a rocky spur some 150 m above the Tangāb River meandering course, commanding the principal gateway to the plain of Firuzabad from central Fars. Ardashir’s builders capitalized on the natural topography of the spur to ensure the castle’s security and its dominant position over the road leading to the plain of Firuzabad (fig. 2). The mountain's steep northern and southern flanks are lined with rubble stone walls, punctuated by occasional fortifications built on prominent outcrops. Qal’eh Dōkhtar castle consists of a sequence of outer defenses encircling a solidly constructed inner fortification with semi-circular bastions. The castle’s main gate was located in a protected corner at the very edge of the cliff on the south side not far from the Palace or the king’s residence. The Palace, made of rubble stones, is an impressive rectangular building, 125 x 35 m. The Palace follows the steep slope of the mountain’s crest and consists of three terraces. The lower terrace is occupied by a long vaulted hallway leading to the middle terrace designed in the form of an eyvān. The upper terrace is where the large domed hall stands. The domed hall was entered through a monumental eyvān 23 x 14 m. The Palace’s walls in rubble masonry were all plastered. The castle’s water supply was ensured through two shafts. To the north, a rectangular shaft was cut out down at the outermost point of the rampart, likely connecting to a tunnel that joined the shaft to the riverbed. A similar structure is found on the southern side.

Archaeological Exploration

Due to its challenging accessibility, perched on the steep cliffs of a rocky plateau, Qal’eh Dokhtar appeared in the travel accounts of the 19th century but remained unvisited until the 1920s. The first known illustration of the castle was published in 1895 by Forsat Shirazi in his Asār-e Ajam, who rightly attributes the fortress to Ardashir Ist. Ernst Herzfeld's 1923 visit to Qal’eh Dokhtar marked a turning point in the archaeological exploration of the castle. During his visit, Herzfeld made a sketch plan of the ruins, although it was never made public. He was the first scholar to identify the dungeon-like rotunda topped by a dome and draw parallels between the stucco ornamentation on the castle’s walls and that found in the nearby Palace of Ardashir. Nearly ten years later, Sir Aurel Stein visited Qal’eh Dokhtar and produced the first comprehensive sketch plan of the ruins along with a description of the castle. The site was the object of detailed topographic surveys between 1966 and 1972 by Dietrich Huff on behalf of the German Archeological Institute. Between 1975 and 1977, Huff carried out excavations in preparation for a UNESCO restoration program on behalf of the Iranian Department of Conservation of Archeological Sites and National Monuments. Qal’eh Dōkhtar was finally inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO as part of the Sasanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars in 2018.

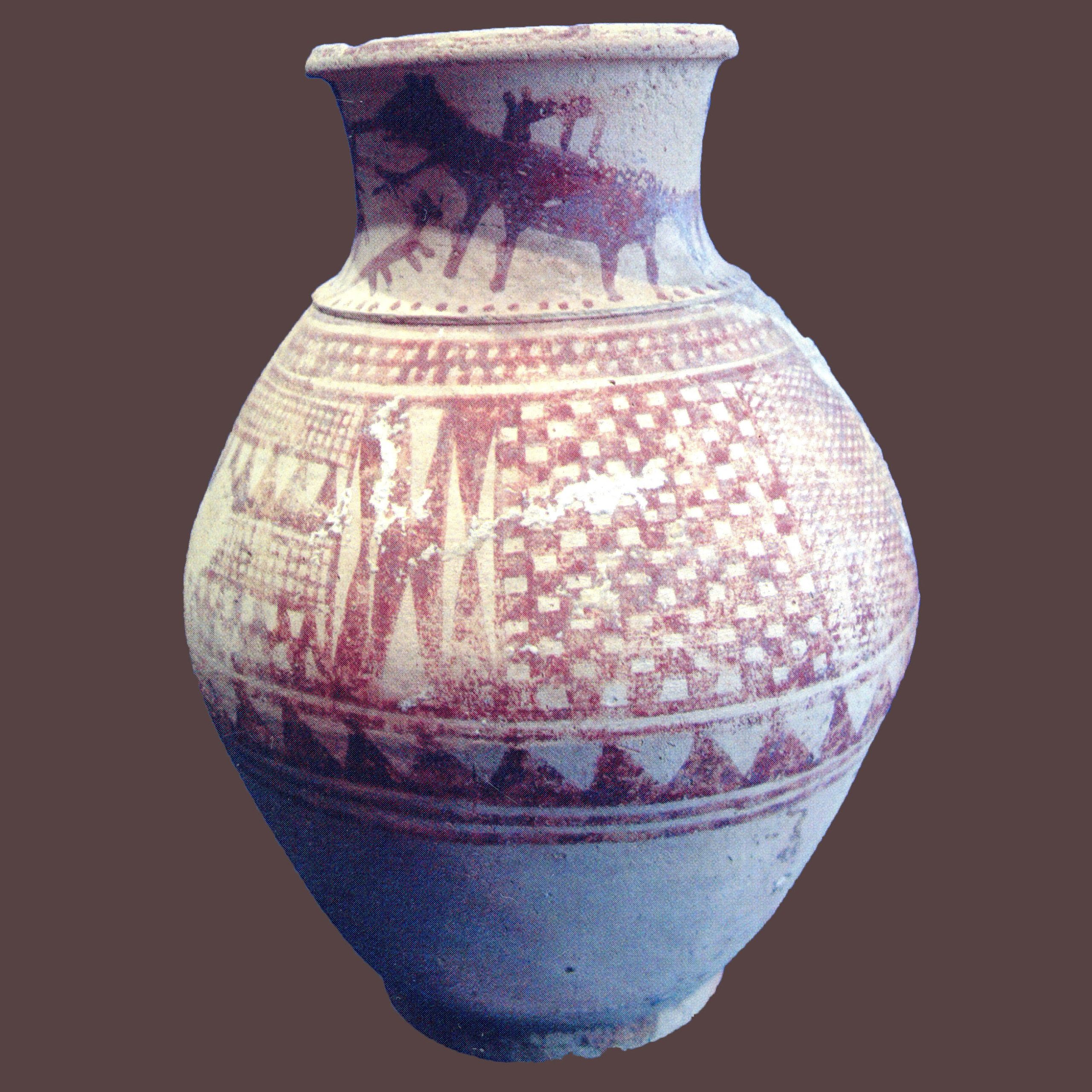

Finds

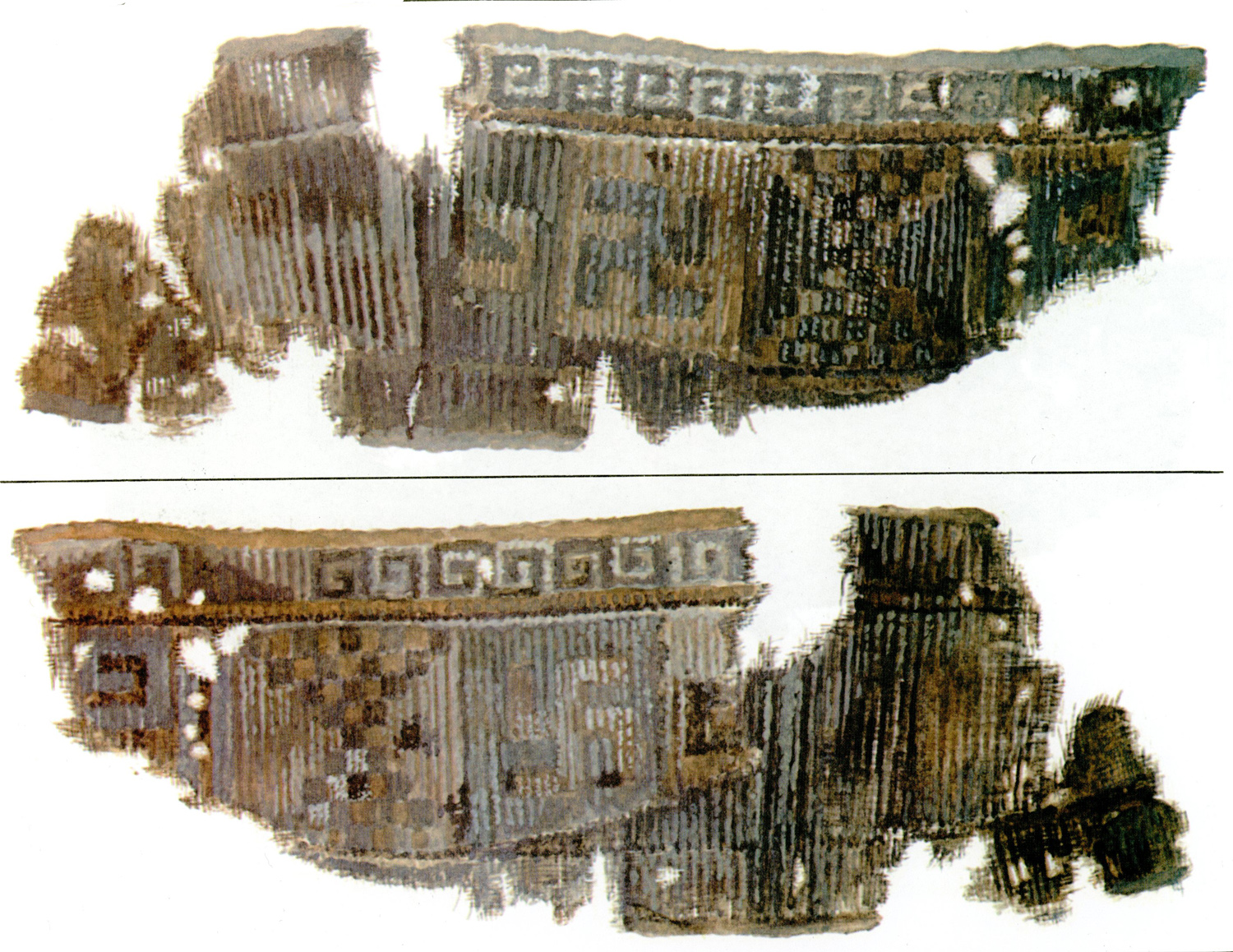

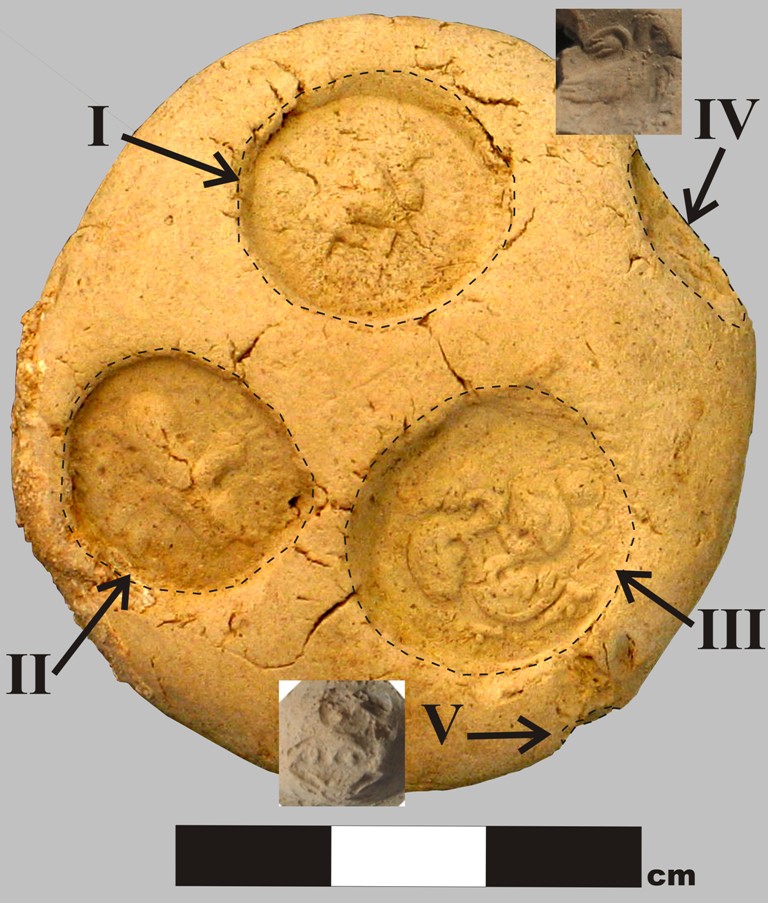

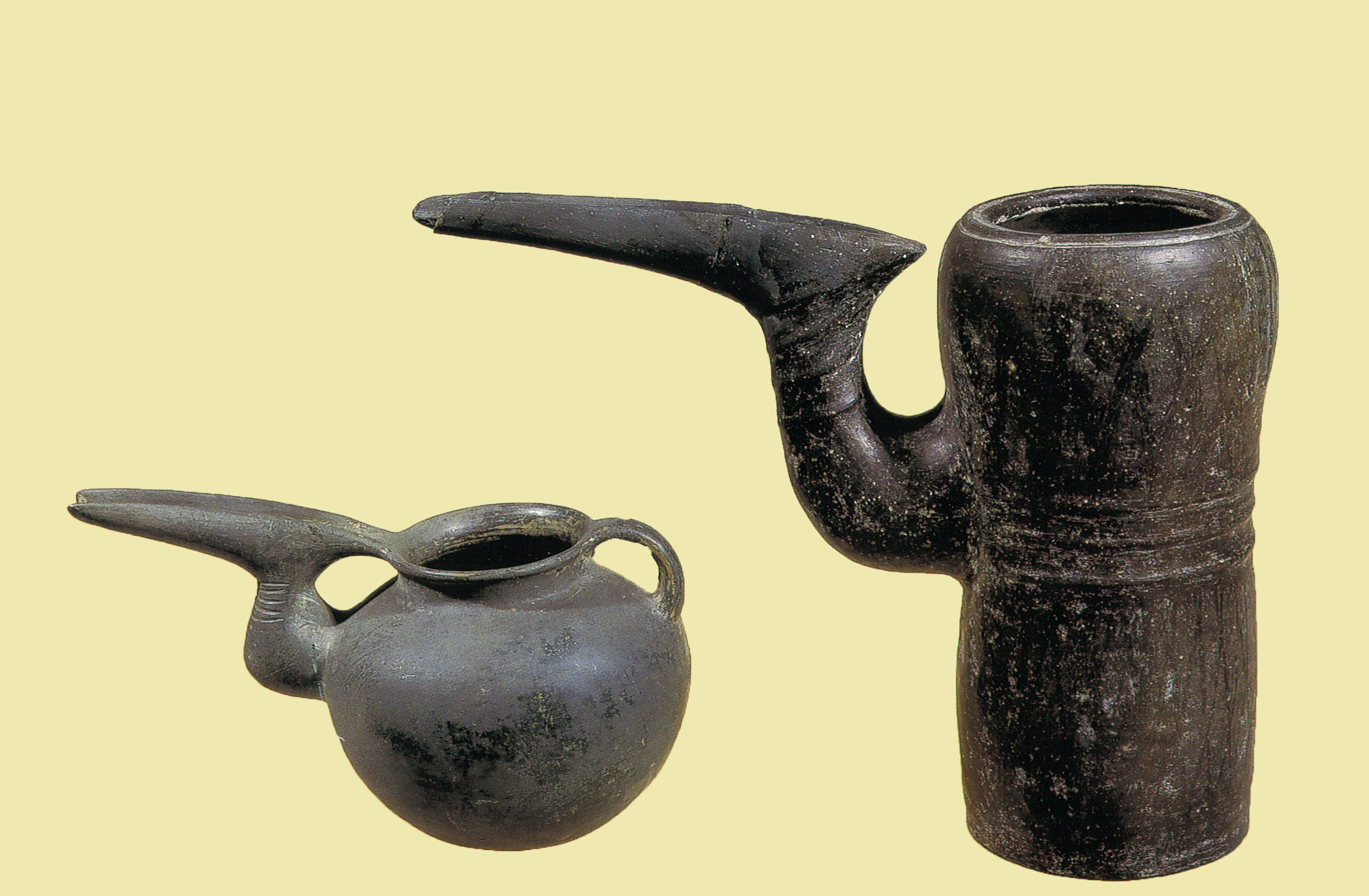

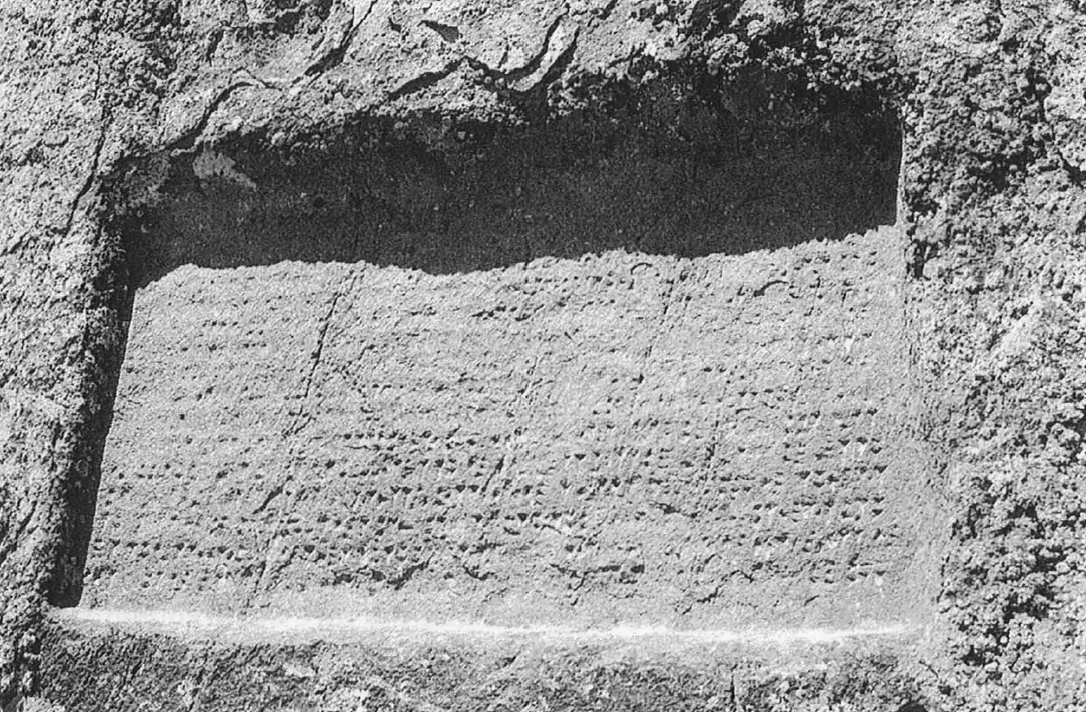

The excavations yielded a small number of finds such as fragmentary stucco decorations and mouldings, typical Sasanian ceramics, a few arrowheads in iron, silver and copper coins, inscribed potsherds or ostraca in Middle Persian.

Bibliography

Byron, R., “Note on the Qal’a-i Dukhtar at Firuzabad,” Bulletin of the American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology, vol. 7, 1934, pp. 3-6.

Forsat al-Dowleh Shirazi, Seyed Mohammad-Nasir, Āsār-e Ajam, Bombay, 1895.

Herzfeld, E., Archaeological History of Iran, London, 1935, p. 95, pl. 14.

Huff, D., “Qal’a-ye Dukhtar bei Firuzabad,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 4, 1971, pp. 127-71.

Huff, D., “An Archaeological Survey in the Area of Firūzābād, Fārs, in 1972,” Proceedings of the IInd Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, Tehran, 29th October-1st November 1973, edited by F. Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1974, pp. 155-179.

Huff, D., “Qal’a-ye Dukhtar, Fīrūzābād,” Iran, vol. 15, p. 172.

Huff, D. and Ph. Gignoux, “Ausgrabungen auf Qal’a-ye Dukhtar bei Firuzabad 1976,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 11, 1978, pp. 117-50.

Stein, A., “An Archaeological Tour in the Ancient Persis,” Iraq, vol. 3, No. 2, 1936, pp. 123-126, plans 3-4.