Name

Saint Thaddeus/Qara Kilisa/Tātāvūs سن طادئوس/قره کلیسا/طاطاووس

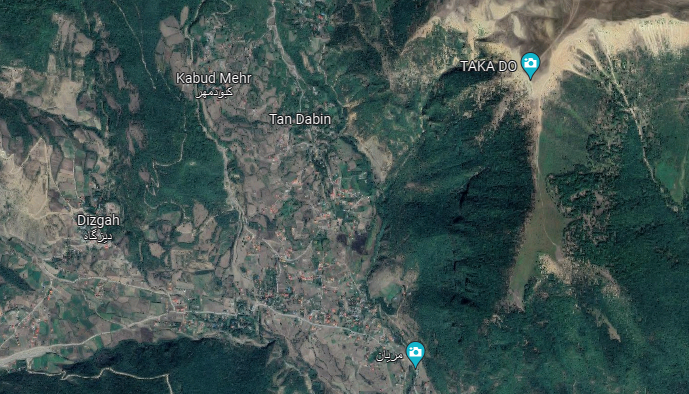

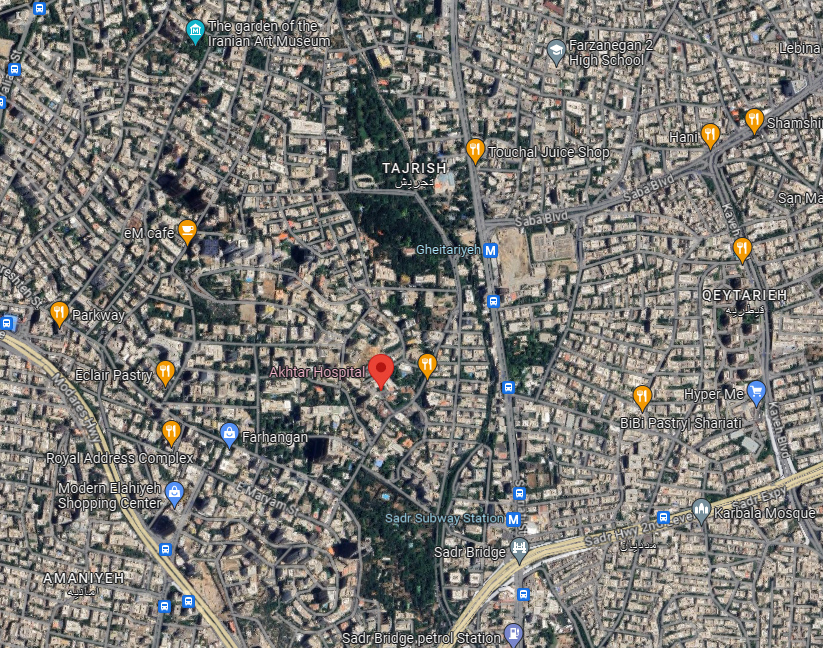

Map

Historical Period

Islamic, Medieval

History and description

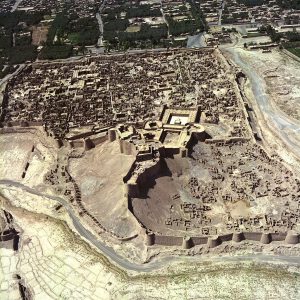

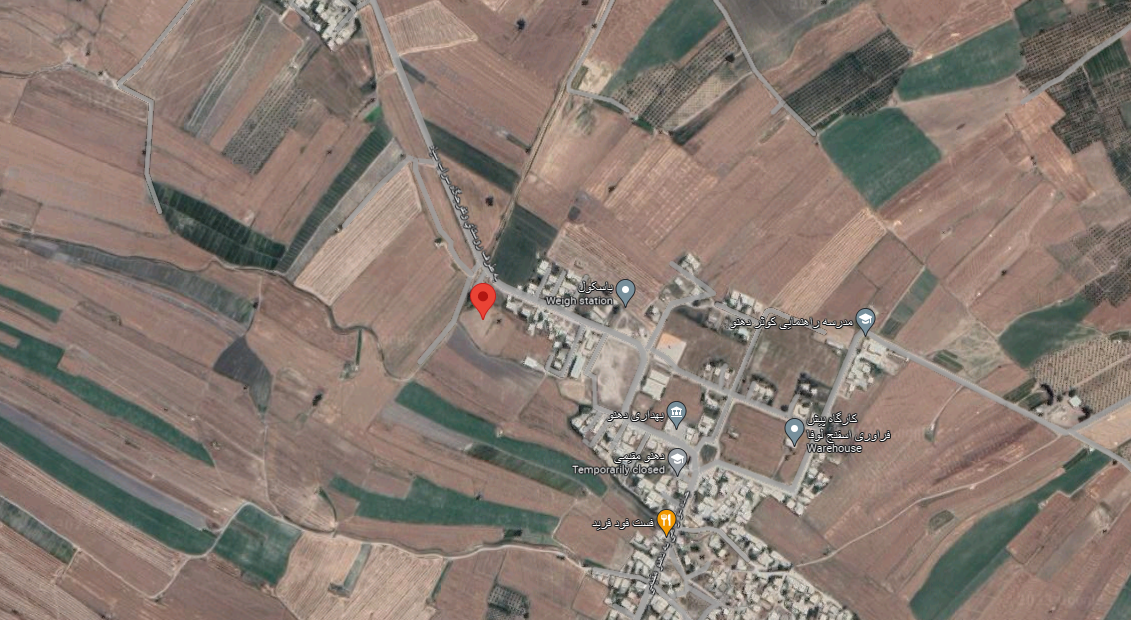

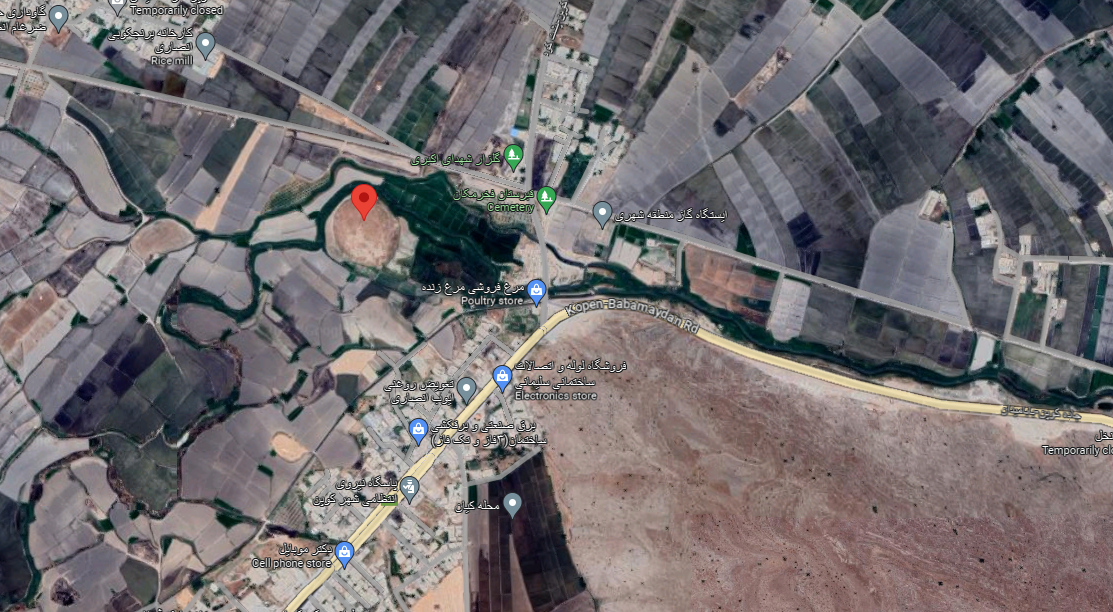

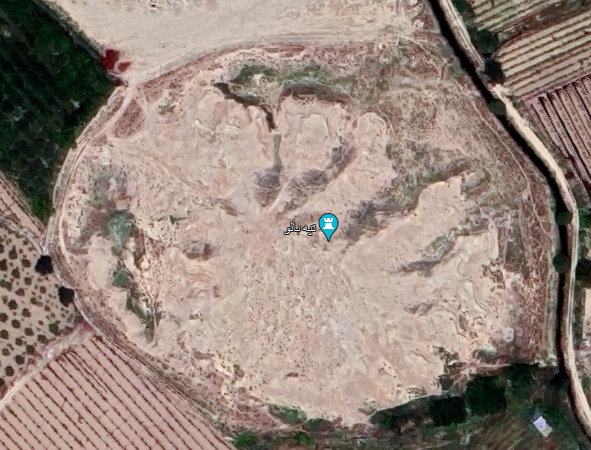

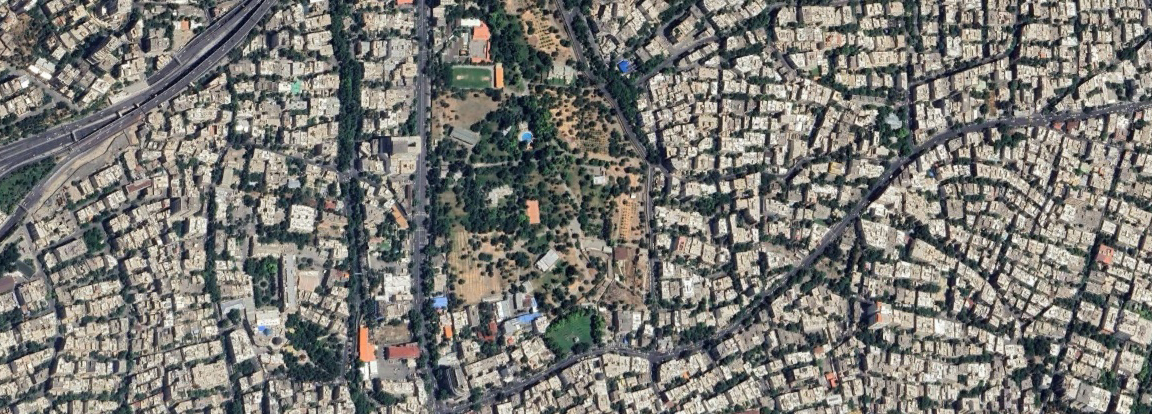

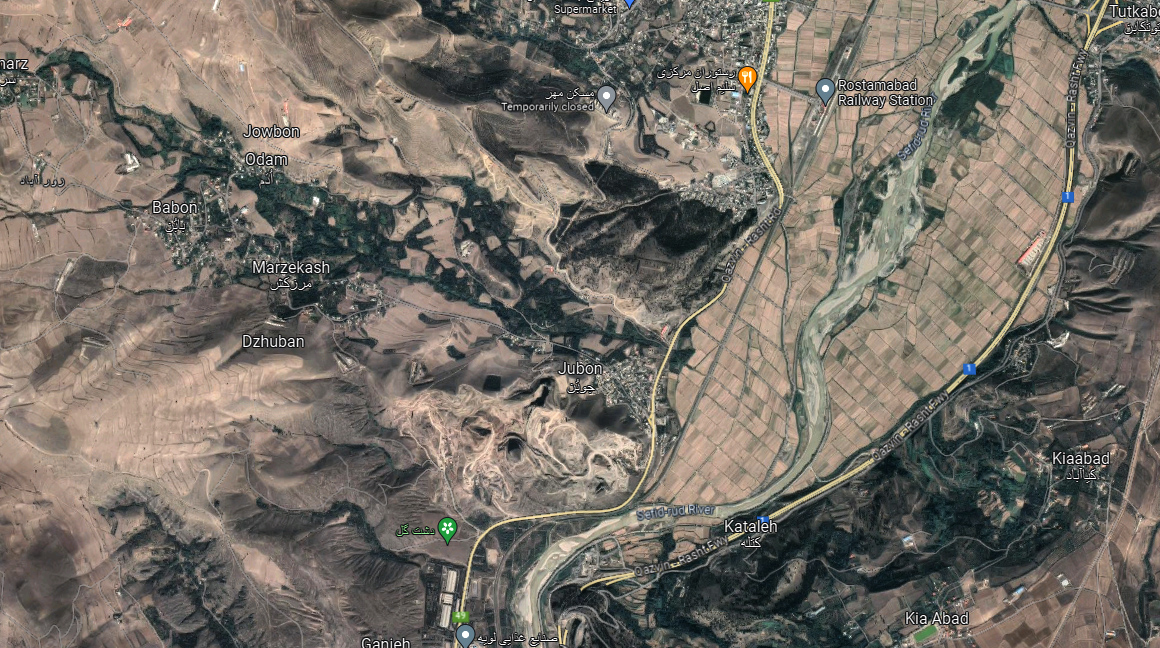

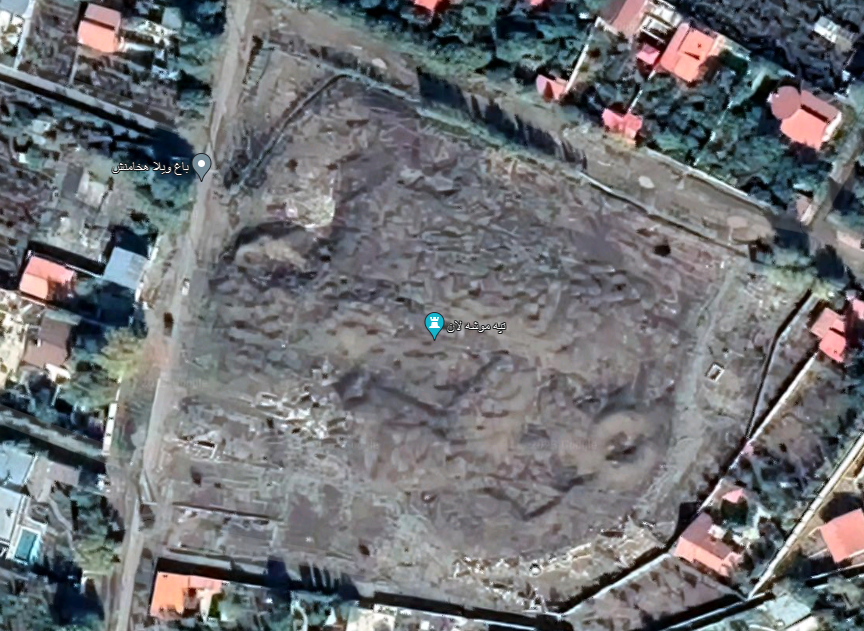

The St. Thaddeus Monastery lies 12 km southeast of the town of Maku, perched at an altitude of 2200 m above sea level. The monastery of St. Thaddeus was built on top of an outcrop, at the foot of which flows a watercourse, separating the monastic compound from its surroundings (fig. 1). The complex comprises the monastic compound and five chapels built in its vicinity. The site includes two adjacent cemeteries, one known as the public cemetery and the other as the spiritual cemetery.

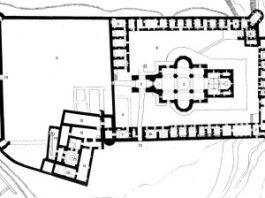

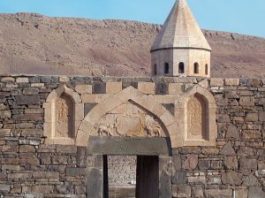

The enclosed monastic complex comprises two spacious courtyards (fig. 2). The main gate, initially 2.50 m wide on the west side, was later reduced to 1.50 m. Adorned with a pointed arch, ornamental motifs, and two khatchkars (tombstone crosses) set into the masonry (fig. 3), the entrance provides access to the outer or first courtyard (44.50 x 49.50 m). In the southeast corner of this courtyard, a set of rooms is designated for the storage of agricultural products. Additionally, there are rooms designed for oil production, a small-scale windmill, an oven, and a fountain. Beyond the southwest wall in this section, there are remnants of walls lining a descending channel, leading to a likely artificial pond used as a water trough for livestock. This courtyard likely served as an open space for pilgrims, as well as for storage and maintenance purposes.

A small door placed on the west wall leads to the second courtyard (about 38.50 x 52 m), surrounded by monks’ living and working rooms, the abbot's quarters, the refectory, the kitchen, and facilities. These rooms, constructed from roughly shaped stone, open towards the courtyard for natural light. The northeastern corner features two semicircular towers, while a substantial tower in the southeast corner provides a vantage point overlooking the valley to the east.

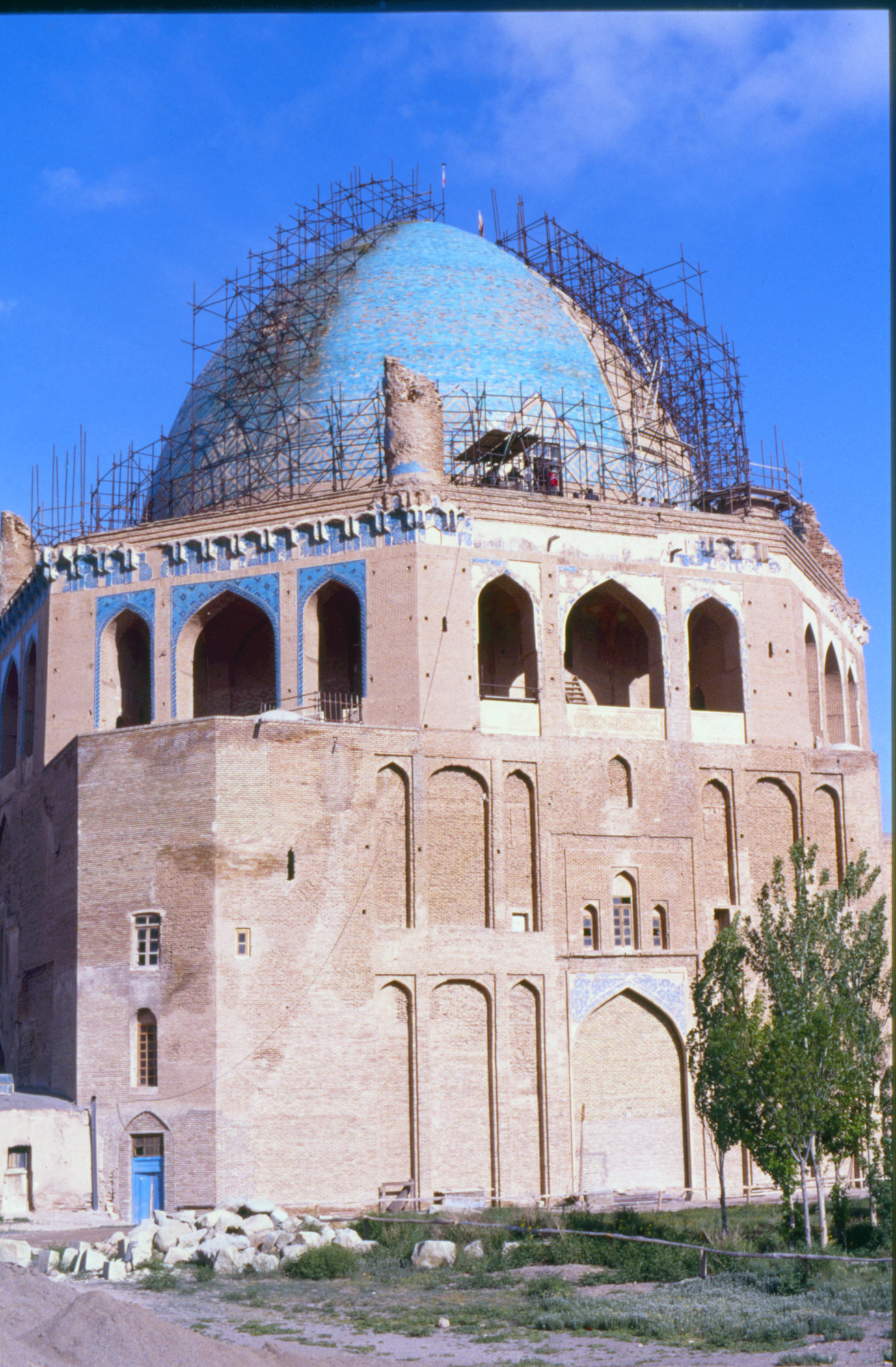

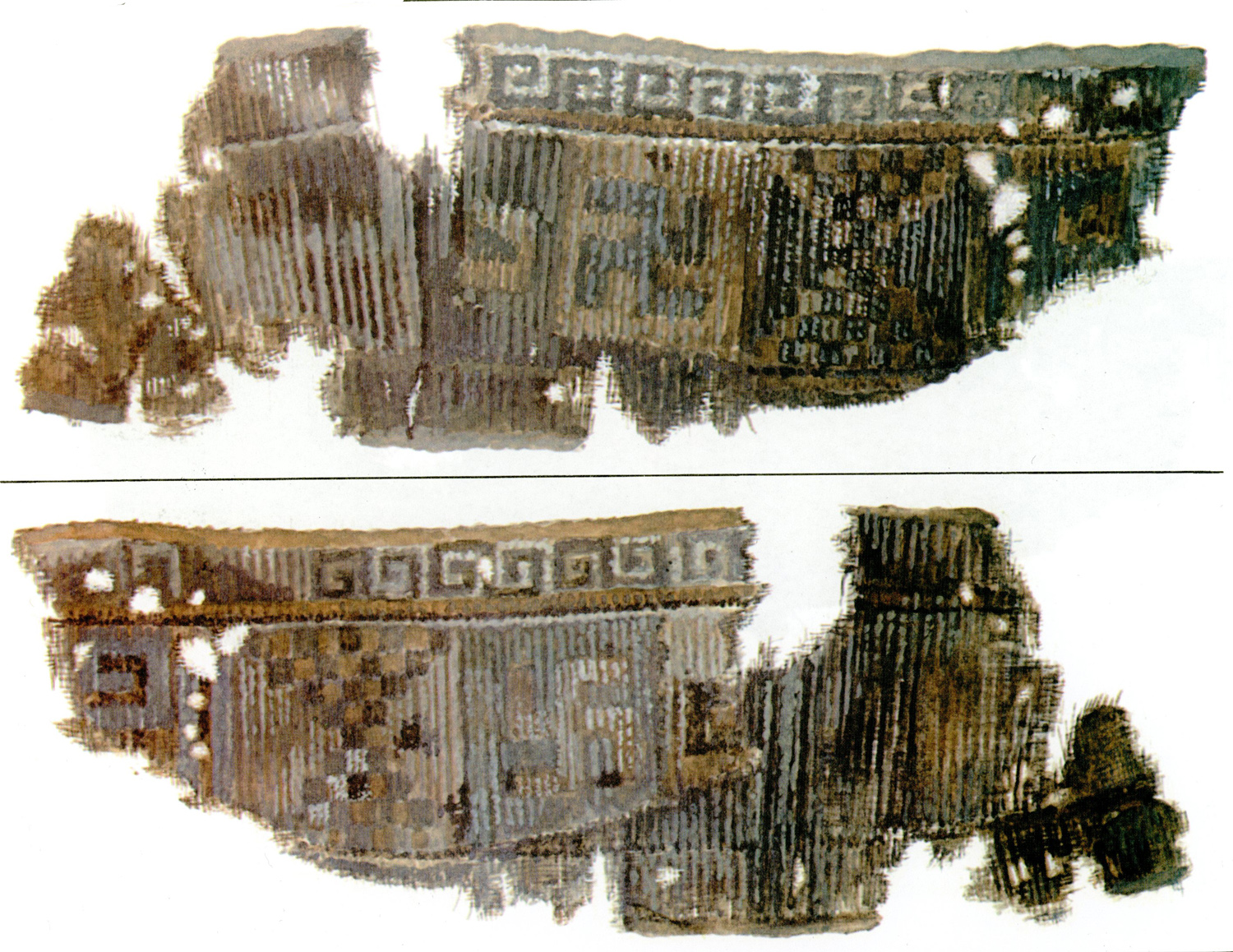

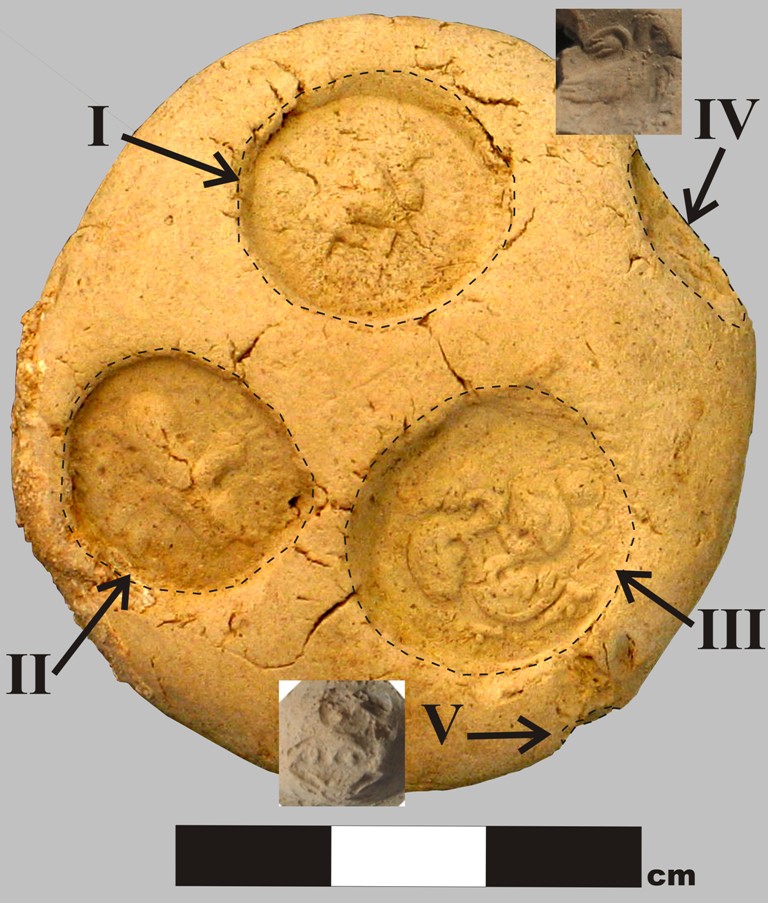

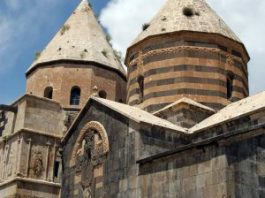

At the heart of this courtyard stands the church (fig. 4), which has undergone numerous changes, including destruction, rebuilding, restoration, and enlargement over time. The entrance is marked by a long inscription in both Persian and Armenian, praising the reconstruction of the church between 1811 and 1820. The church is built on a Greek cross layout. Its length is 34 m; its width ranges from 15 m to 23 m. The church includes three main parts: a grand, decorated but unfinished bell tower, reminiscent of Sasanian chāhār-tāqs (fig. 5), the White Church, and the sanctuary and apse referred to as the Black Church. The White church was attached to the small ancient church in the 19th century. Four pillars support the four vaults, on which rests the dome, whose drum is pierced with twelve windows (fig. 6). The dome is 18.20 m high. The interior is reminiscent of Romanesque architecture in Europe. The entire outer walls of the White Church are decorated with bas-reliefs. The iconographic repertoire used for the decoration of the façade has been derived from both Iranian and Christian sources.

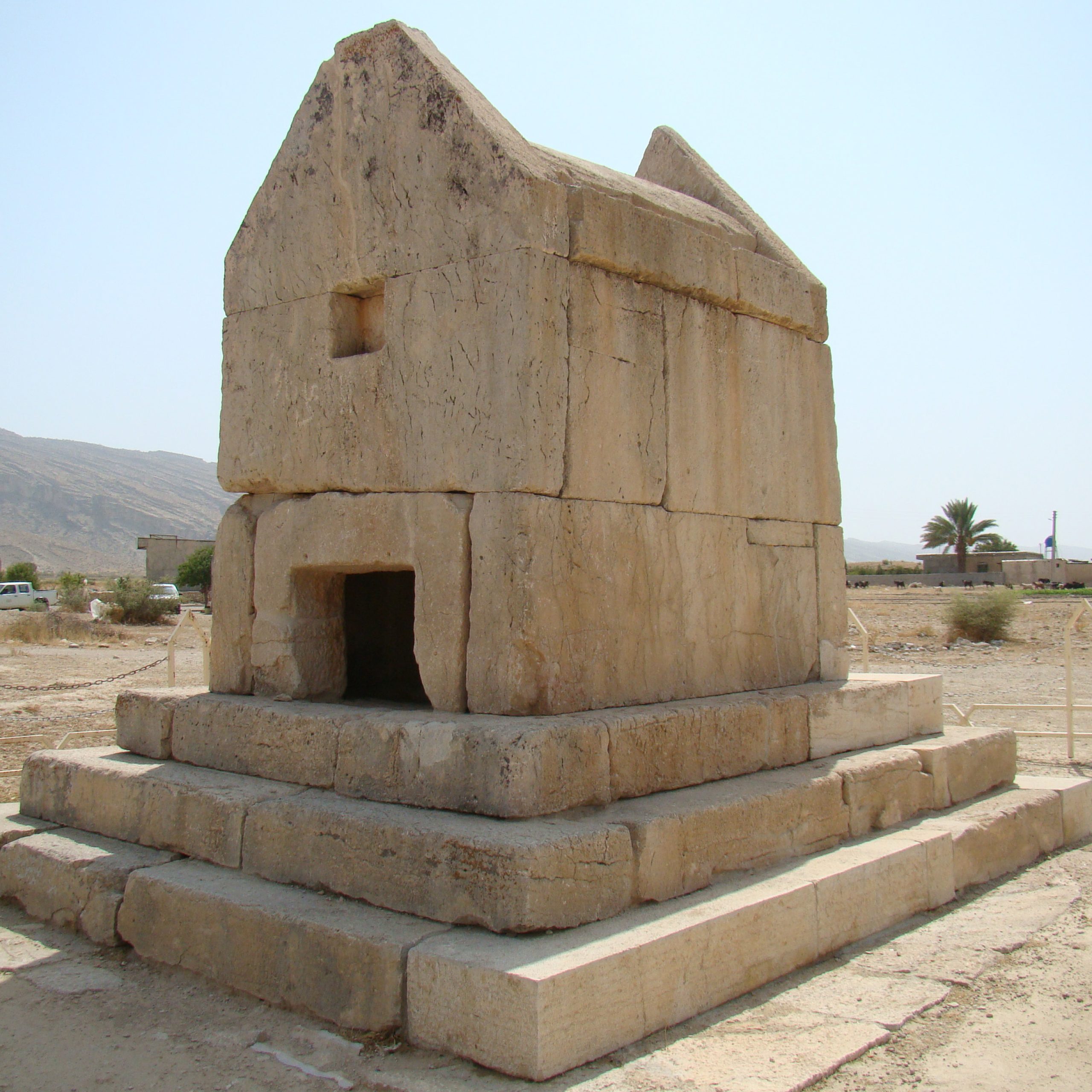

The Black church now constitutes the sanctuary of the St. Thaddeus church (fig. 7). It is flanked by side chapels and the adjacent cross-shaped hall is crowned by a dome rising above the crossing. These two architectural elements form the original church, characterized externally by a rectangular plan and distinguished from the newer section by the blackish-gray color of its stones. It is these dark stones that have earned the building the name Qara Kilisa (Black Church). The layout of this surviving part of the Black church, which lacks its original nave and narthex, resembles the common plan type of Armenian churches from the 9th to the 13th century. Notably, the resemblance to the church of Achot III of Ani, dating from the 10th century, may suggest that the ancient part of St. Thaddeus (destroyed in 1319) had likely been built during the same period. An inscription in Armenian has the date of 1329 for the reconstruction of the church.

In keeping with Armenian tradition, this specific location was selected because Saint Thaddeus erected the earliest church upon the ruins of a temple, some parts of which are still thought to remain, forming the foundation of the old section. Thaddeus was martyred in 66 A.D. by the order of King Sanatruk of Armenia. Moses of Khorenatsi, the Armenian historian writing in the fifth century, recounts that Saint Thaddeus, one of the Twelve Apostles, was invited by King Abgar of Armenia. But Abgar’s successor, Sanadruk, returned to paganism and ordered Thaddeus’ assassination. Thaddeus’ body was then laid to rest at the present-day site of the monastery. The conversion of Armenia to Christianity, achieved in 301 A.D. by St. Gregory the Illuminator, is linked to the legend. St. Gregory supposedly erected the first church on Thaddeus’ tomb in 239 A.D. The monastery’s founding date remains unknown, with no reference to the Thaddeus legend in its remains.

Historical documents referring to the Council of Karin (Erzerum) in the year 633 highlight Archbishop Tiratour from the Artaz region (Maku), likely associated with the St. Thaddeus monastery. These records affirm the church’s well-maintained condition and the continued operation of the monastery during that period. Later, the relics of St. Thaddeus and Princess Sandokht were mentioned in the manuscript of Haysmavourk dated 771. Some 10th-century texts refer to the monastery’s location between two major religious centers of Etchmiadzin and Aghtāmār.

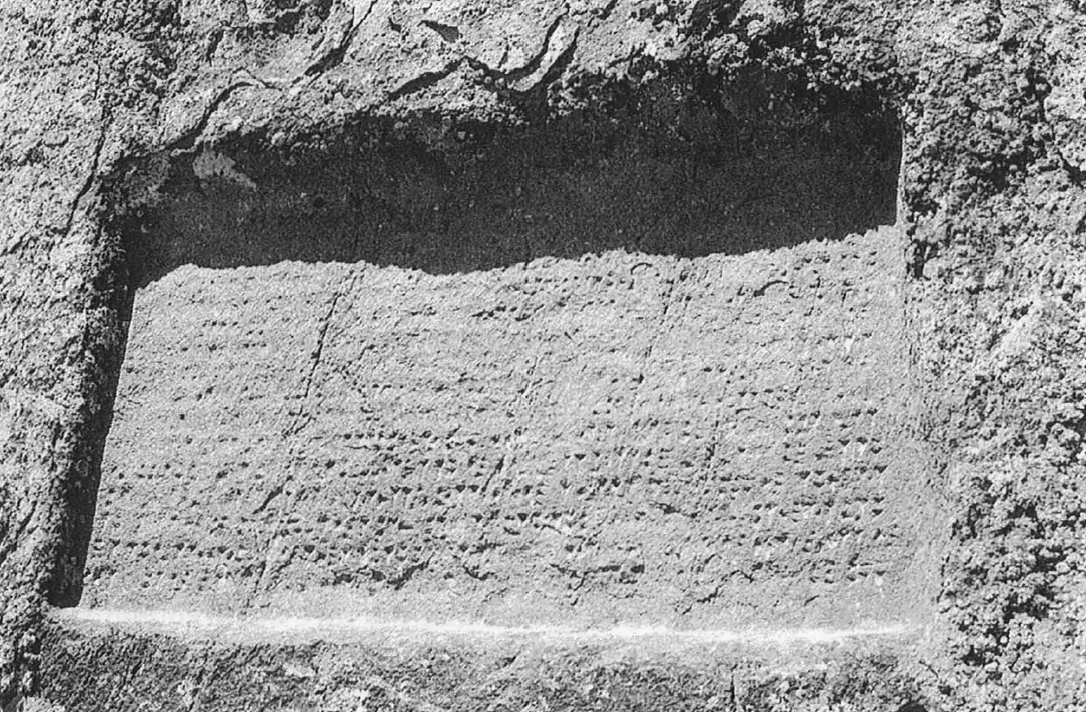

The Mongols invaded the area in 1242, sacking the monastery. Under the rule of the first Ilkhān of Persia, Hūlagū (1256-1265), support for Christians and Armenians prevailed. Hūlagū’s wife, Doghuz-Khātun, who had converted to Christianity, favored the Armenians, resulting in the restorations and tax exemptions for the St. Thaddeus monastery. Despite a generally auspicious policy during the Ilkhāns’ rule, records from Arghūn’s reign (1284-1291) reveal that the monastery was occasionally plundered. A powerful earthquake in 1319 caused severe damage, resulting in the death of seventy-five monks. Bishop Zachariah organized the reconstruction of the church, completed in 730/1329, using white stone for some parts to contrast with the original black stone. Not much is known of the original church’s layout, but some scholars suggest the new church may have been modeled after Etchmiadzin. An Armenian inscription on the north wall commemorates the monastery’s restoration.

A significant historical account from that 14th century comes from Clavijo, the ambassador of the king of Spain, who traveled in the Maku region during Timūr’s invasion. He reports that Timūr chose to spare this particular region and the monastery of St. Thaddeus.

In the late 15th century, a decree issued by Abōlmozaffar Rōstam Bahādōr, a ruler of the Aq-Qūyūnlū dynasty in northwestern Iran, addressed a conflict between Zachariah, the bishop of St. Thaddeus, and the archbishop of Armenians in Etchmiadzin. The document forbade the archbishop from interfering in the daily affairs of the St. Thaddeus monastery. Zachariah continued as the bishop until 1511 and later ascended to the position of archbishop of Armenians, maintaining this role until 1520.

In the early 16th century, during the advent of the Safavid dynasty, Shah Ismail and his successor, Tahmasp, supported the Armenians in northwestern Persia. Shah Tahmasp issued a decree safeguarding the St. Thaddeus monastery and its lands. In 1604, Shah Abbas, in conflict with the Ottoman Empire, depopulated the area between the two empires, forcing many Armenians to relocate to Isfahan in southern Iran. Although there is no direct record of the St. Thaddeus monastery’s evacuation, records show that the bishop initiated restorations in 1650, suggesting possible damage during the forced evacuation in the Turko-Persian wars of the early 17th century.

Sparse 18th-century records suggest the monastery was well-maintained. Nader Shah’s 1155 H./1734 decree affirmed the monastery’s land integrity. In the late 18th century, Aqā-Muhammad Khan, founder of the Qajar dynasty, invaded Georgia, leading to the plunder of Armenian monasteries, including St. Thaddeus, in 1787. In the early 19th century, the Russian Empire’s expansion into the Caucasus targeted eastern Armenia as a key military objective. St. Thaddeus monastery is mentioned again in the context of Russo-Persian wars (1804-1813, 1826-1828). The first description of the monastery in nineteenth-century Western travel books is by Colonel William Monteith of the Madras Engineers who briefly mentions the monastery. He arrived in Persia in 1810 as part of a British contingent assisting and training the Persian army against Russia. Monteith passed through Azarbaijan and visited St. Thaddeus likely in 1817. Monteith writes that the St. Thaddeus monastery was one of the largest in the region and that the Armenian community was under the protection and patronage of Crown Prince Abbas Mirza.

Crown Prince Abbas Mirza, leading Persian forces against Russia, recognized the importance of a supportive Armenian population. He sponsored the restoration of Armenian churches, in northwestern Iran. In 1810, Archbishop Simeon Bsnūni, aided by Persian government funds, conducted extensive restoration at the St. Thaddeus monastery. The White Church, a significant part of the monument, constructed in the style of earlier buildings, dates from this period. An inscription by Abbas Mirza, commemorating the restoration in verse, was placed at the church’s main entrance in 1229 H./1814 (fig. 8). During the Qajar rule (1779-1924), the monastery of St. Thaddeus experienced a relatively favorable policy. For instance, in 1878, Naser al-Din Shah issued an order directing a portion of taxes from the region’s villages to be allocated for the maintenance of St. Thaddeus.

The Armenian churches in Iran have long been dismissed in early Western studies on Armenian art and architecture. It was the Austrian art historian, Josef Strzygowski, who first mentioned the St. Thaddeus monastery in his general survey of Armenian architecture. He noted that the monastery housed the members of the German Christlicher Hilfbund in Orient in 1897. This coincides with the time when the first known photograph of the monastery was taken and published in the journal Der christliche Orient (see bibliography). Hans Fischer of the German aid mission to Armenians left a vivid description of the monastery and its setting in the last years of the nineteenth century. He writes that the Armenians of northwestern Iran could live peacefully and safely under the protection of the Prince of Maku. He goes on to recount that the “father of this prince had no children. He then made a pilgrimage to the monastery of St. Thaddeus, and not long after, a son was born to him,” who became the ruler of the land. The mission decided to rent the monastery which was the residence of an Armenian abbot along with its deacon and dependents.

In the early 20th century, amid turmoil, war, and revolutions, the St. Thaddeus monastery served as a resistance center for Armenian revolutionaries from 1903-1908. Upon the return of the region's population to their lands in 1918, the monastery was reported to be in good condition. In 1930, during the Soviet takeover of Armenia, there was a proposal to move the seat of the Catholicos from Etchmiadzin to St. Thaddeus. However, in 1946, following the repatriation of Armenians to Soviet Armenia, the monastery area was abandoned until the retreat of the Red Army from northwestern Iran. Gradually, the St. Thaddeus monastery regained its glory and became the site of an annual summer celebration for the Armenian population. Every July, believers embark on a three-day pilgrimage to the St. Thaddeus Apostle Monastery in northwestern Iran. This sacred journey honors two distinguished saints: St. Thaddeus, a pioneering apostle in the propagation of Christianity, and St. Sandokht, the inaugural female Christian martyr. The celebration has been inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Archaeological Exploration

In the late 19th century, Vartaped Khatchik Dadian, a minister from Etchmiadzin, studied the Maku region, visited St. Thaddeus, and documented inscriptions at the site. Yervand Frangian, a teacher at the Armenian school of Tabriz, reported on the state of St. Thaddeus in 1903. Haig Adjamian conducted a detailed assessment of the monastery in 1959/60. The first comprehensive architectural study, featuring accurate plans, drawings, and photographs, was published by Wolfram Kleiss from the German Archaeological Institute in Tehran in 1967. Subsequent thorough restoration work at St. Thaddeus began in 1969 under the auspices of the National Office of the Restoration and Preservation of Historical Monuments of Iran. In the years 2006 and 2007, the St. Thaddeus Monastery was registered on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.

Bibliography

Adjamian, H., Sourb Tadei Vank, [The Monastery of St. Thaddeus] Tehran, 1349/1970 (in Armenian).

Fischer, H., “Das Kloster des hl. Thäddaus,” Der Christliche Orient, Berlin, 1897, pp. 497, 510-513.

Haghnazarian, A., Das Armenisches Thaddäuskloster in der Provinz Westaserbaidjan in Iran, Aachen, 1973.

Hakopian E., Sourb Thadei Vank [The Monastery of St. Thaddeus], Tehran, 1999 (in Armenian).

Hovian, A., “Qara Kelisa”, Barresihā-ye Tārikhi, vol. 2, No. 5, 1346/1967, pp. 195-210.

Kleiss, W., “Das Kloster des Heiligen Thaddäus (Kara-Kilise) in Iranisch-Azerbaidjian”, Instanbuler Mitteilungen, vol. 17, 1967, pp. 291-305.

Kleiss, W., “Le monastère arménien de Saint Thaddée en Azerbaidjian (Iran)”, Archéologia, No. 19, 1967, pp. 72-75.

Kleiss, W., H. Seyhoun, Kh. Ter Ghrighourian, and A. Haghazarian, St. Thadei’ Vank, Documents of Armenian Architecture, vol. 4, Milan, 1971.

Monteith, Col. W., “Journal of a Tour through Azarbayjan and the Shores of the Caspian”, Journal of Royal Geographical Society, vol. 3, 1833, p. 49.

Strzykowski, J., Die Baukunst der Armenier und Europa, vol. 2, Vienna, 1918, pp. 651-653.

Van Esbroeck, M., “Le rois Sanatrouck et l’apôtre Thaddée,” Revue des Études arméniennes, nouvelle série, vol. 9, 1972, pp. 241-283.

DOWNLOAD AS PDF

DOWNLOAD AS PDF