Name

Dārābgird دارابگرد

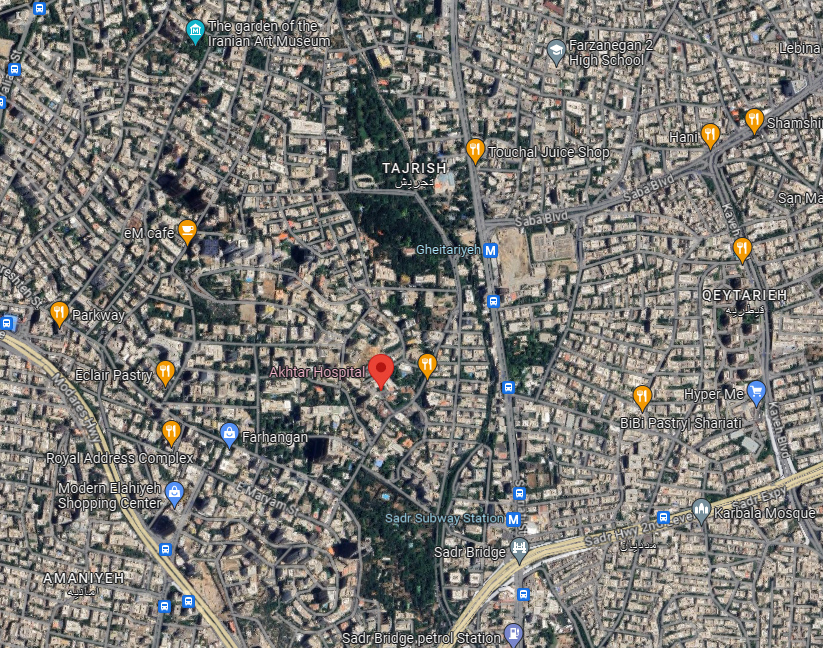

Map

Historical Period

Achaemenid, Parthian, Sasanian, Islamic

History and description

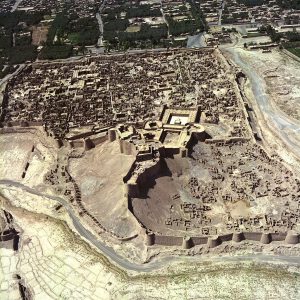

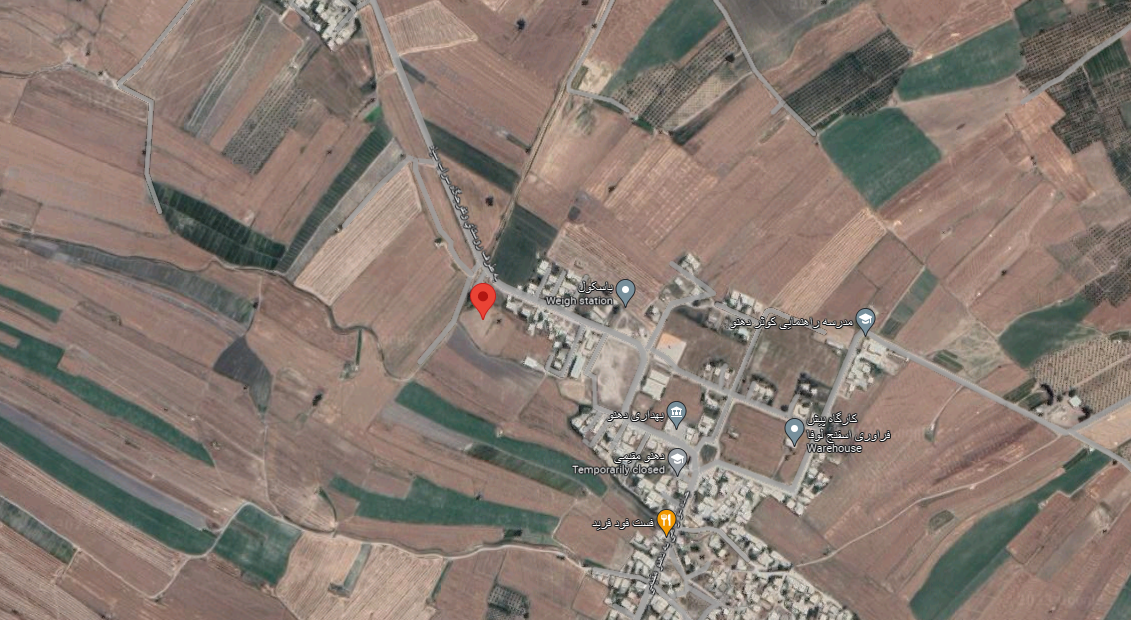

Dārābgird is an early Sasanian town in eastern Fārs, from where Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanian Empire, (r. 224–242 A.D.) began his vocation as its argbed (military commander or citadel chief). It is therefore not surprising that Dārābgird (fig. 1) may have served as a prototype for Ardashir Khwarrah or the round city of Firūzābād that became the seat of Ardashir even before he established the Sasanian Empire in 224 A.D. Tabari attributes its foundation to Darā, son of Bahman, who is probably Darius the Achaemenid (The History of al-Tabari, 693). Ibn Balkhi, the presumed author of the Farsnāmā confirms the name of the founder and describes the site as follows: (Le Strange, Description of the Province of Fars in Persia; Le Strange and Nicholson, The Fārsnāmā of Ibnu’l-Balkhi):

This city was founded by Darā, son of Bahman. It was built circular as though the line of circumference had been drawn with compasses. A strong fortress stood in the centre of the town, surrounded by a ditch kept full of water, and the fortress had four gates. But now the town lies all in ruins, and nought remains except the wall and the ditch. The climate here is that of the hot region, and there are date-palms. The streams of running water are of bad quality. A kind of bitumen [mūmiyā] is found [near Dārābjird] at a place up in the mountain, which bubbles up and falls drop by drop. Also there is a rock-salt found in these parts which is of seven colours where it comes to the surface of the ground.

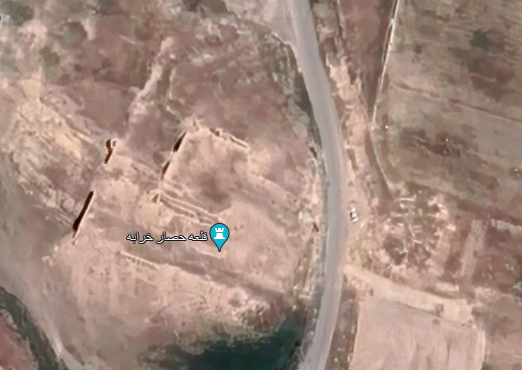

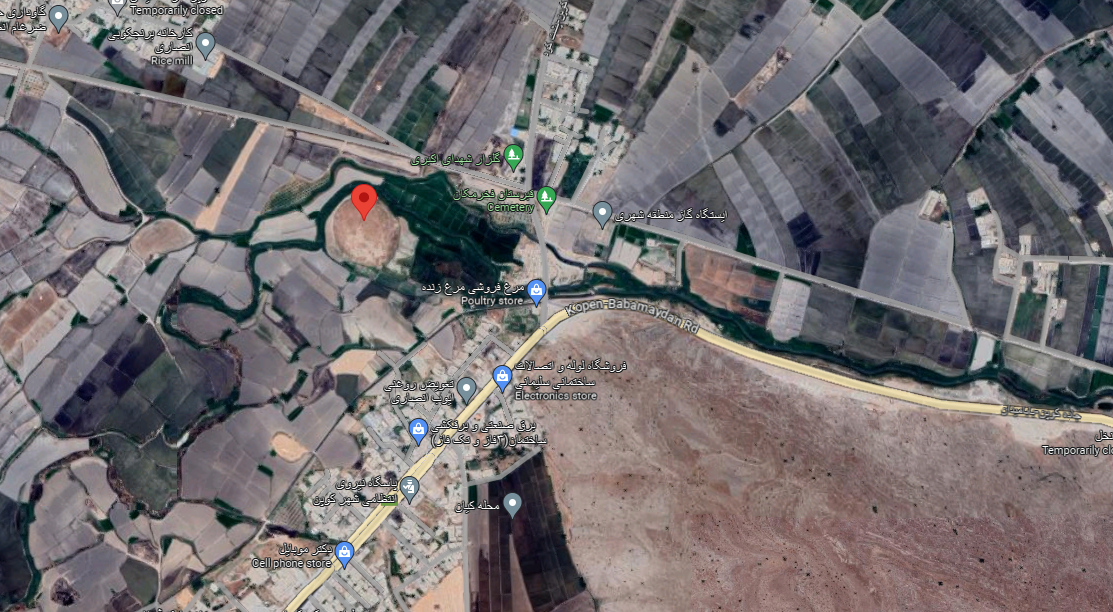

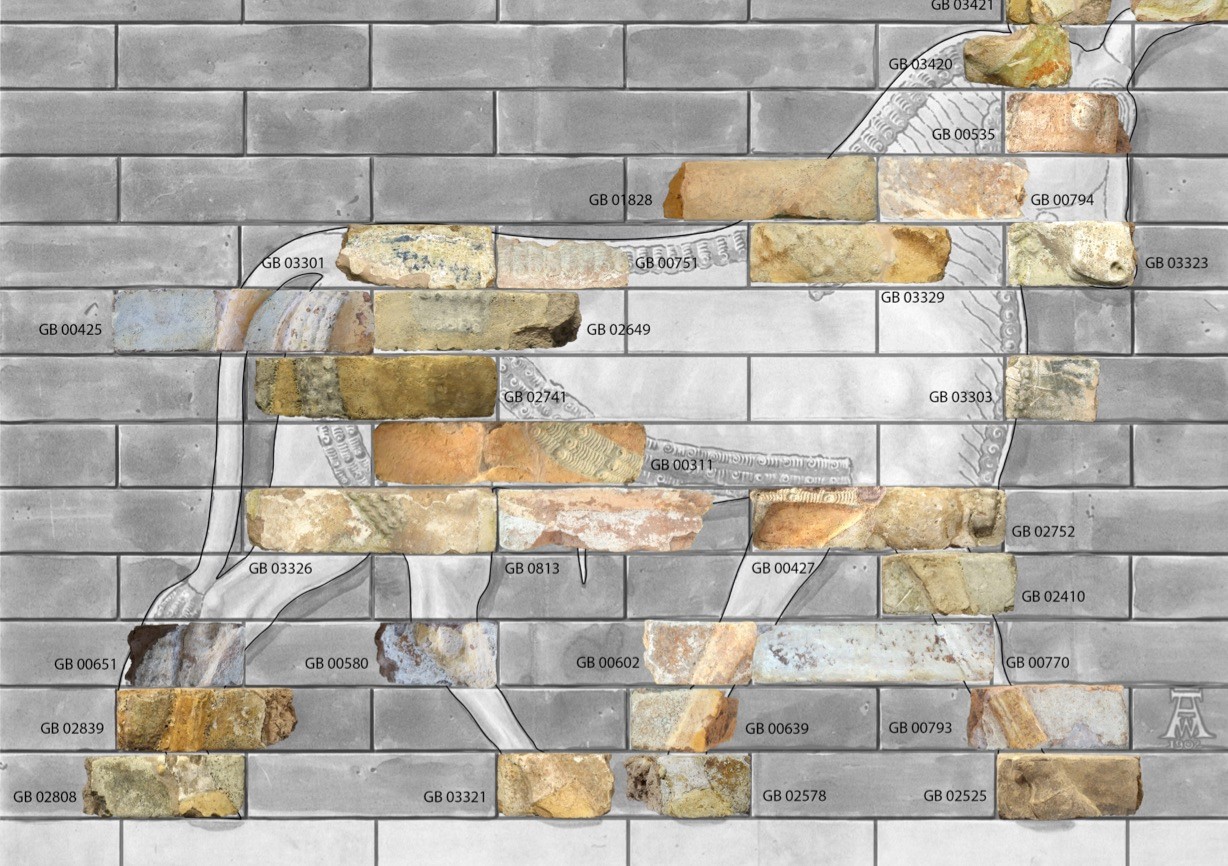

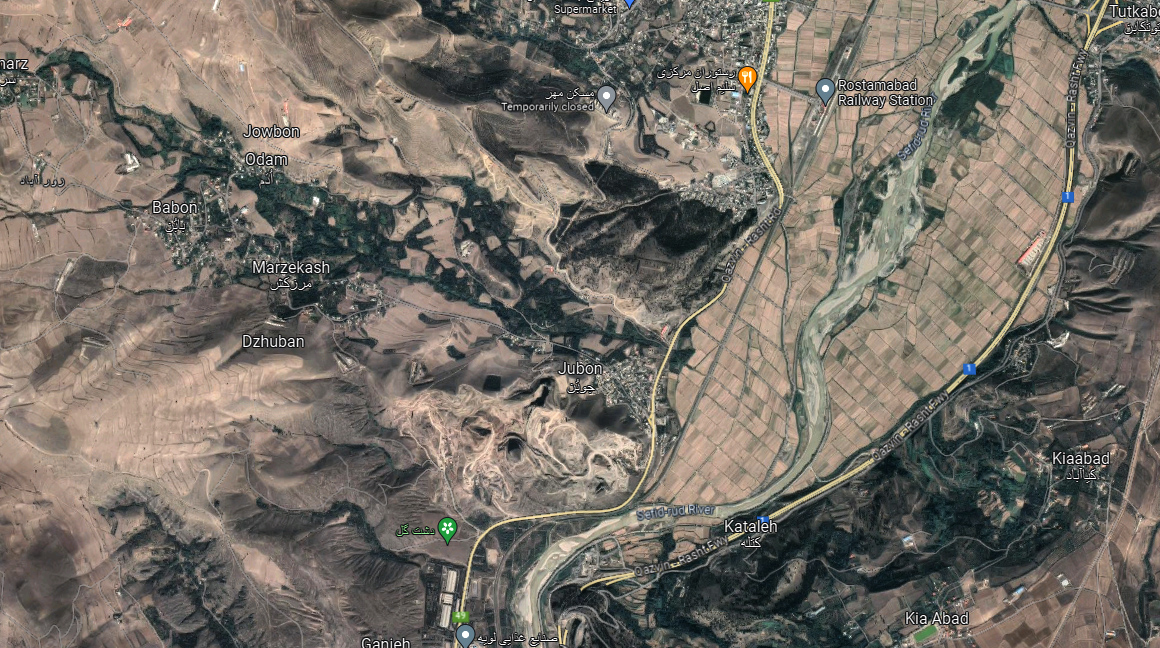

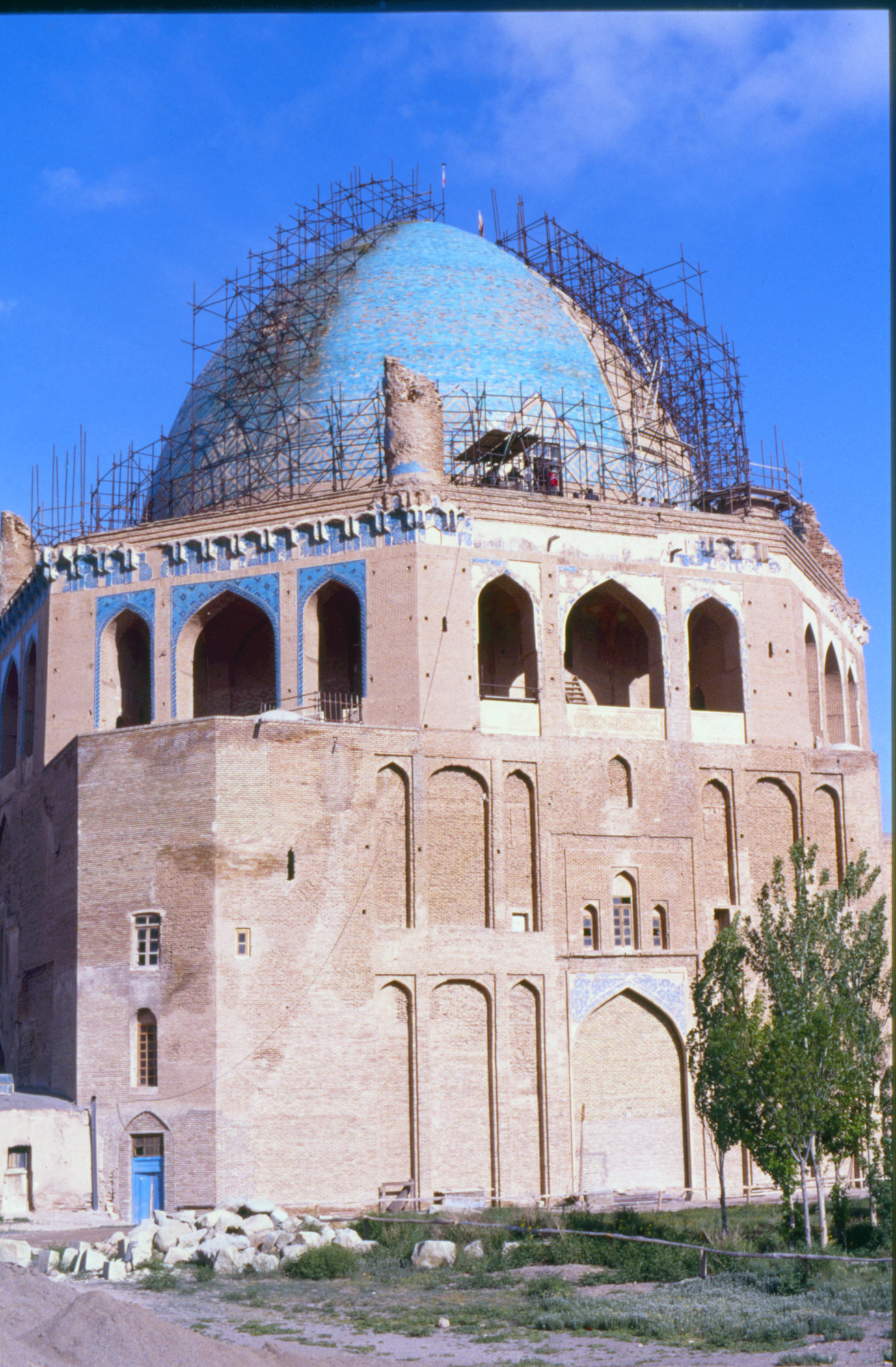

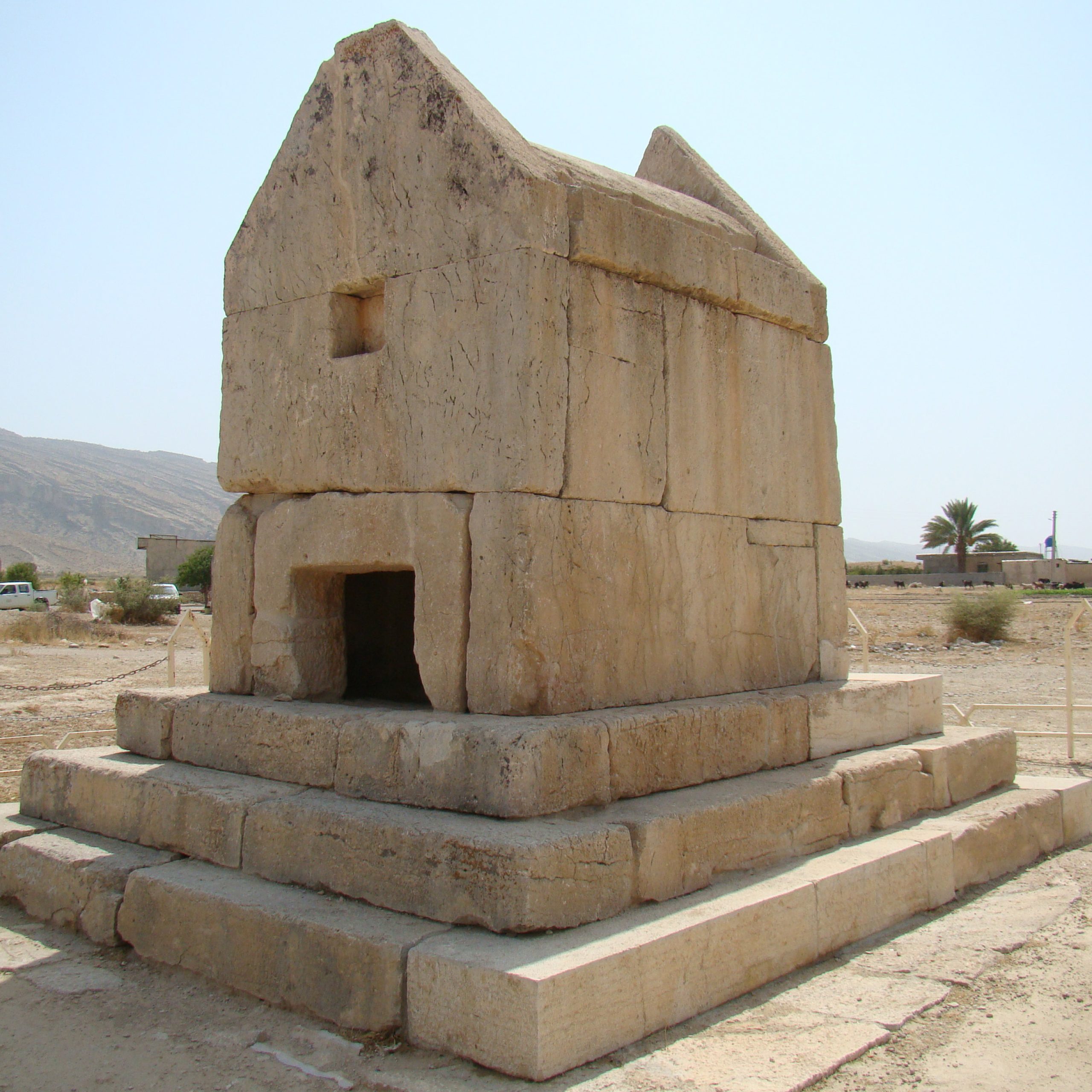

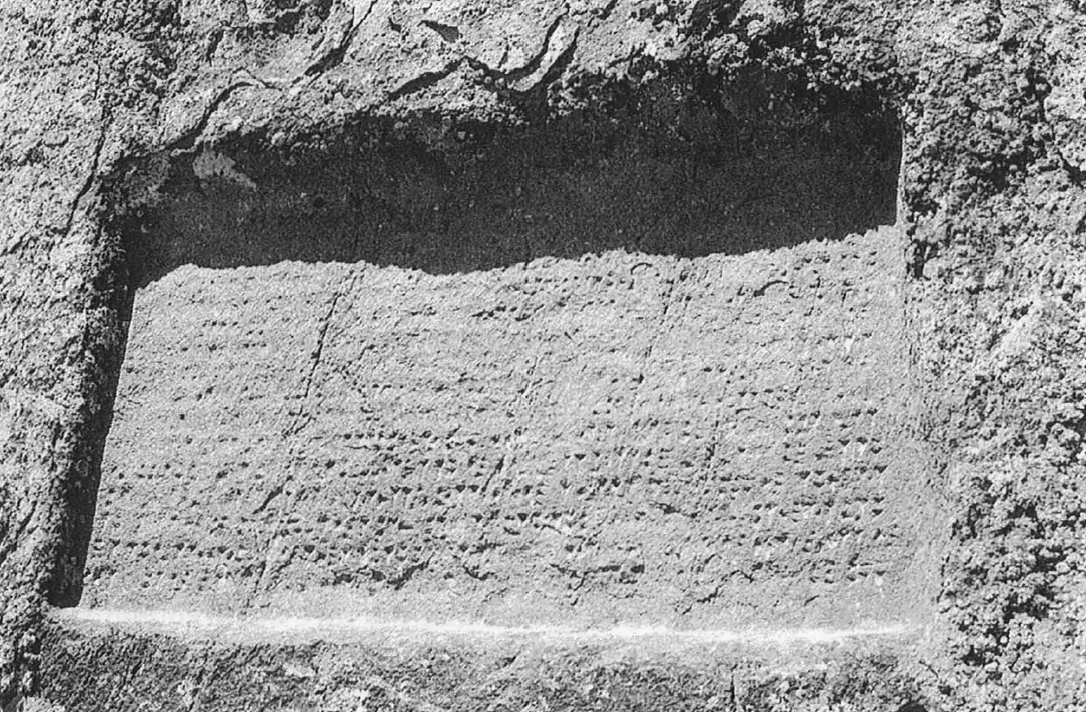

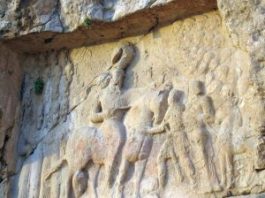

The account of Ardashir’s association with Dārābjird was documented by Tabari (The History of al-Tabari, 815-816). The rock-relief (fig. 2) is located 7 km to the northeast of Dārābgird. The relief, 9.18 x 5.43 m, depicts a victory scene of Shapur I over Roman emperors. The identification of the king is debated. Some interpret the relief as a lesser-known victory of Ardashir in his early years, c. 230, while others see it as an early representation of Shapur I’s triumph in his Roman campaigns. All the tenth-century authors wrote that Dārābgird was a prosperous city that outlived the Sasanian Empire. Muqqadasi refers to its “good products” like mats, rugs, textiles of various qualities, nuts, dates, and spices, as well as its gardens, particularly its palm trees, wells, and yakhchāls (ice houses), along with its bitumen mine (Ahsan al taqāsim, p. 422). Istakhri describes the city as having a strong city wall and moat where an abundance of shrubs and ivies made it difficult to traverse. He mentions the city’s four gates and a mountain at the center, resembling a “large dome.” Istakhri also notes the town’s unhealthy conditions, and Stein interprets it as “a result of malaria bred by the great fosse with its stagnant water” (Masālik va mamālik, p. 110). Dārābgird is referred to in Firdowsi’s Shahnama when King Darab commended the building of the city and its round wall. In the fourteenth century, the city seems to be in ruin (The Geographical Part of Nuzahat-al-Qulūb, p. 138).

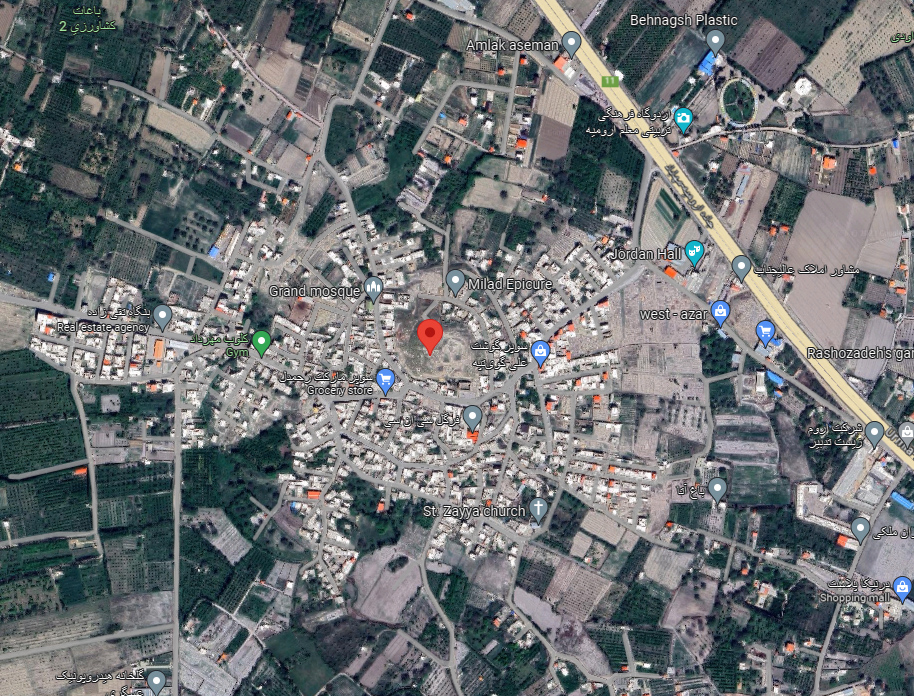

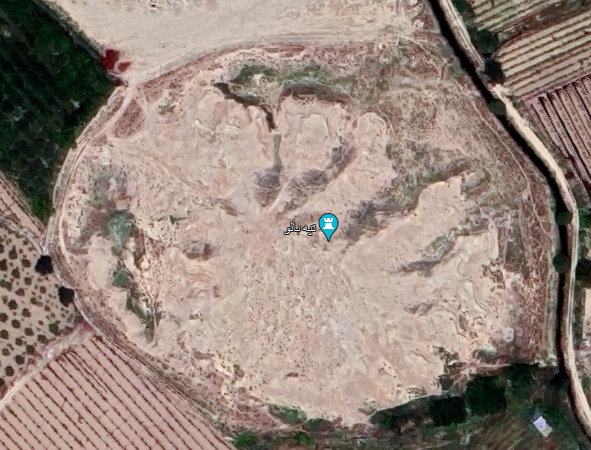

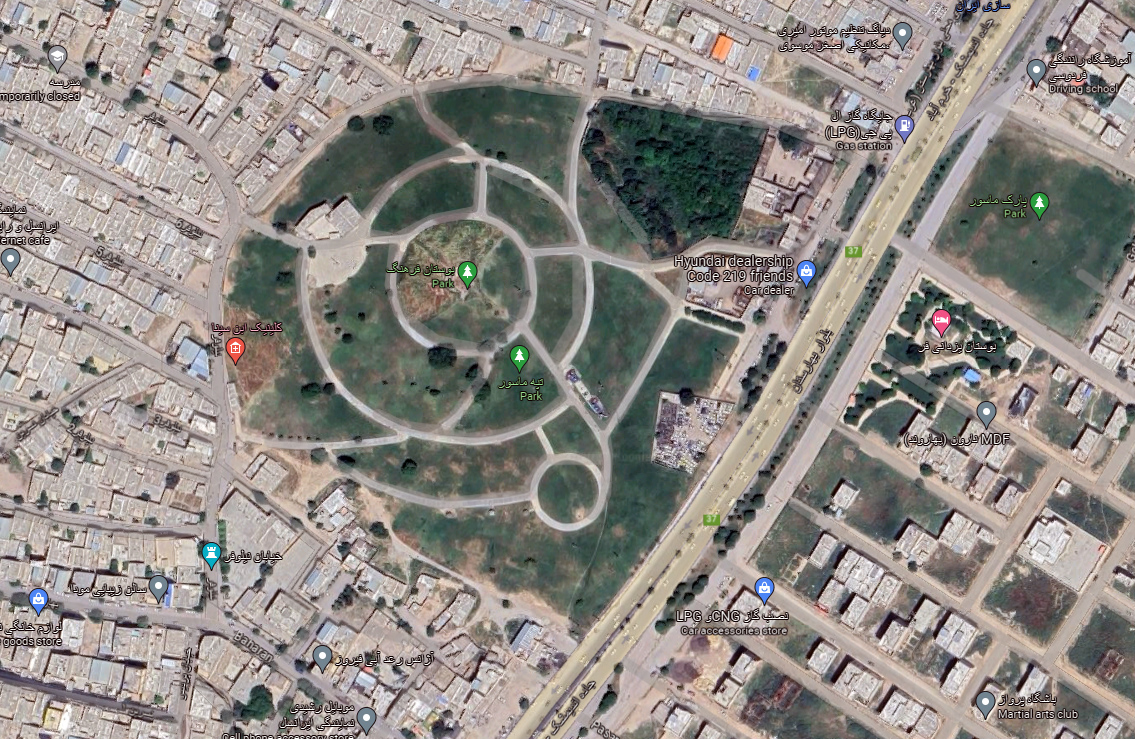

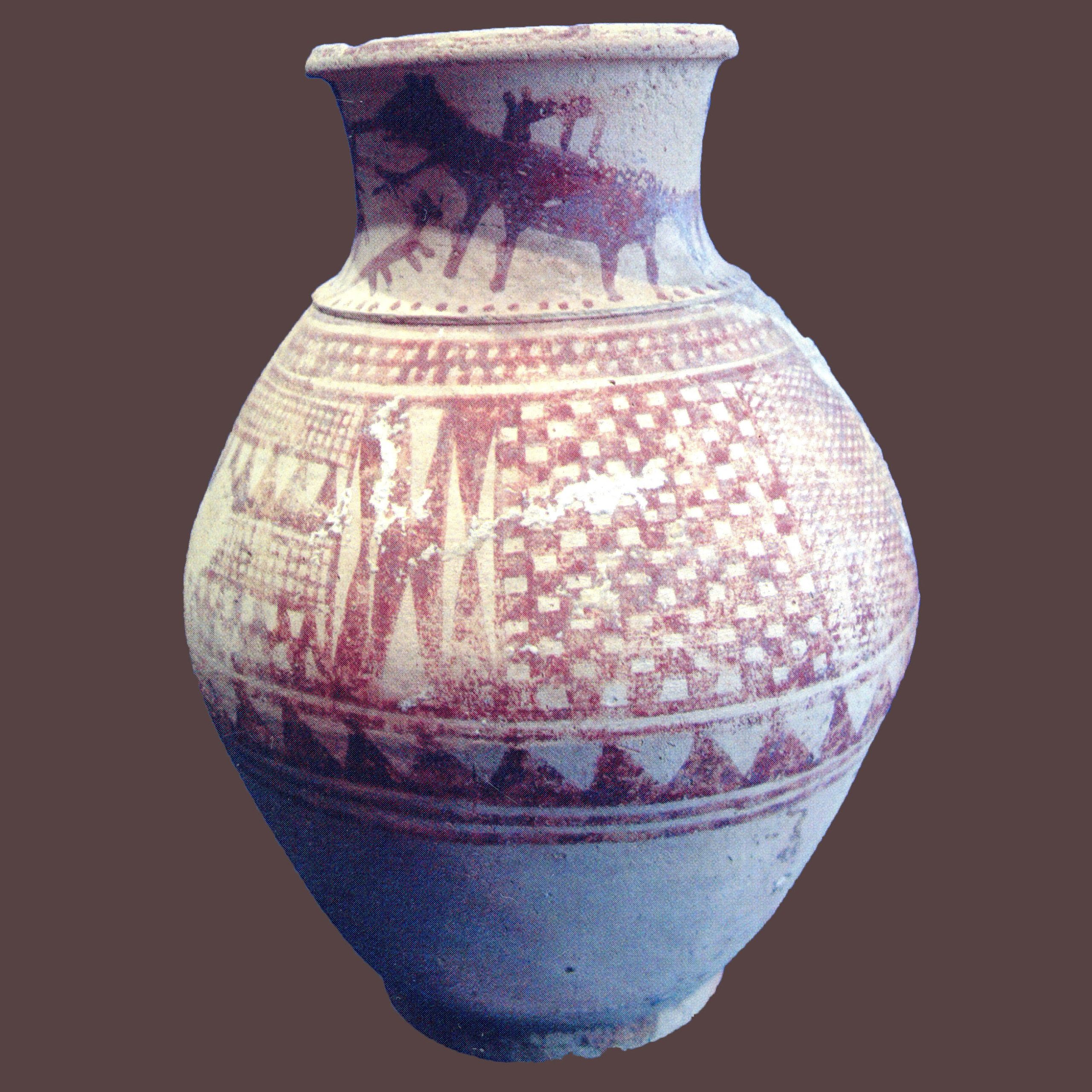

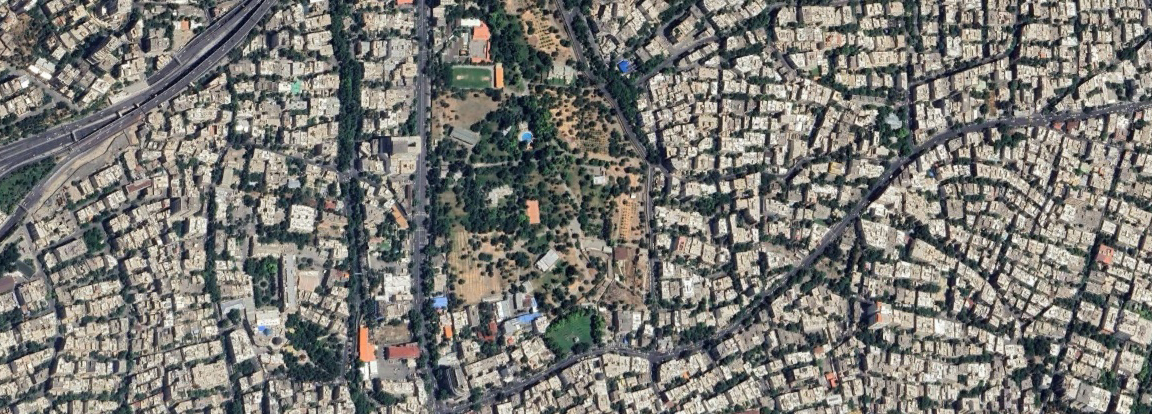

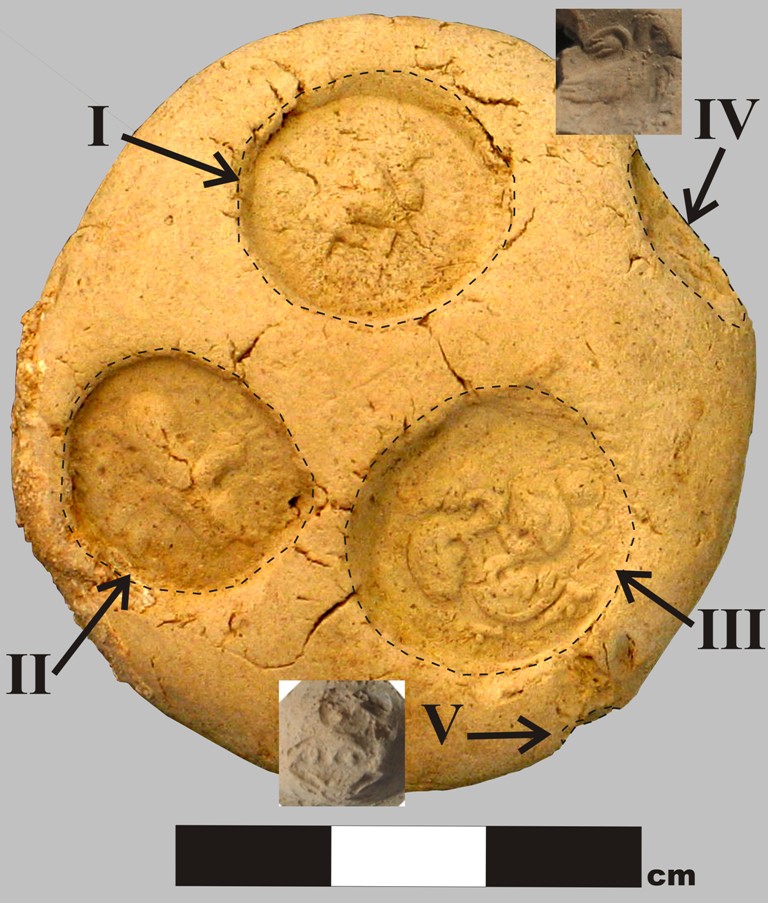

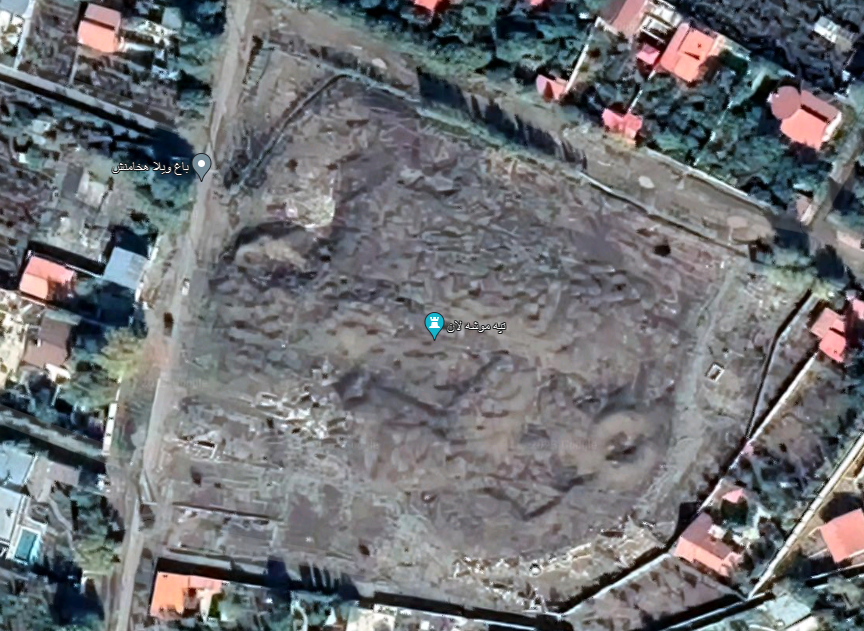

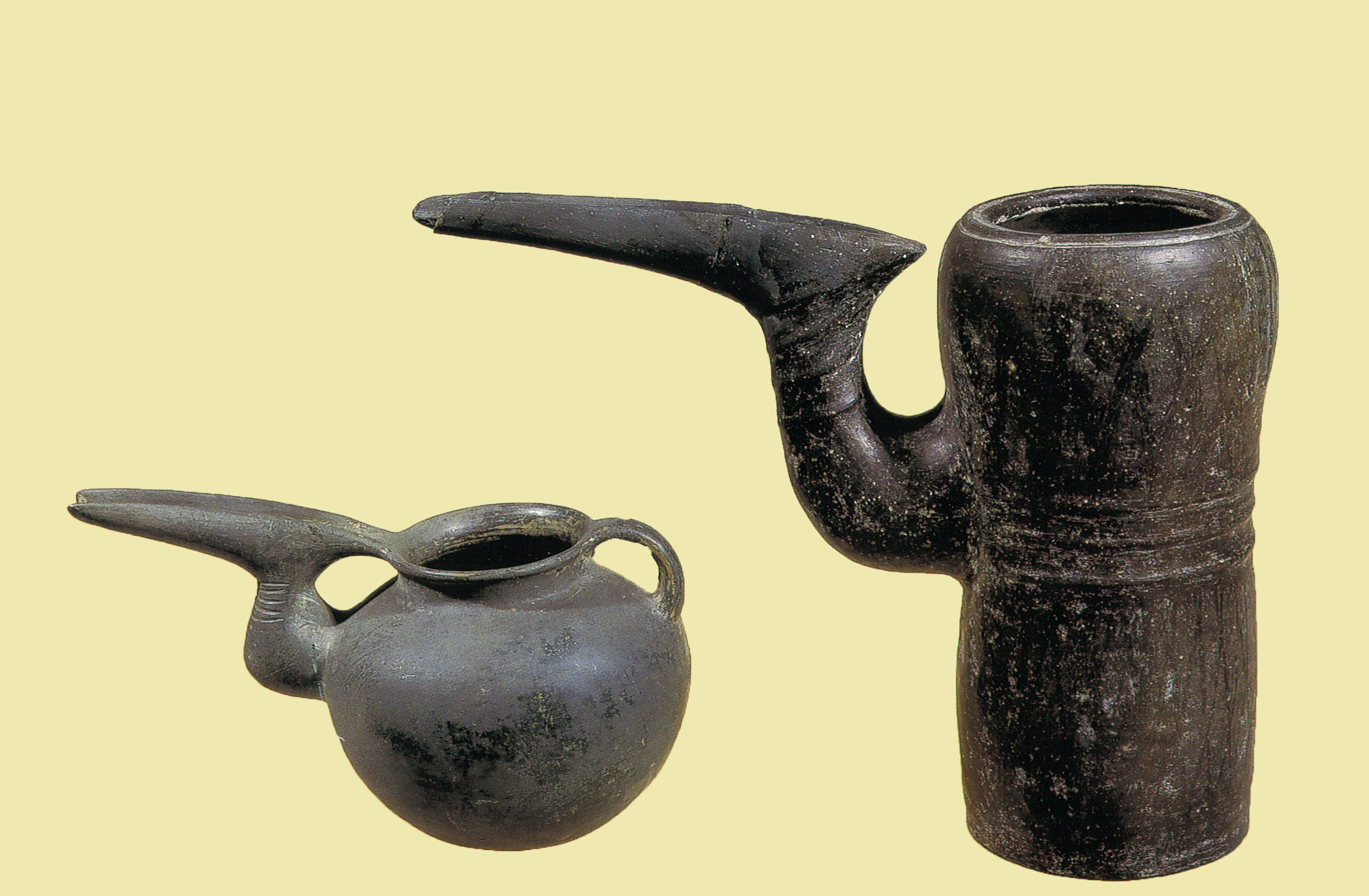

The town is surrounded by a circular mud-brick and stone wall about 1,900 m in diameter (fig. 3). Though circular, the wall is irregular and not as precise as the wall of Ardashir Khwarrah. As Huff rightly notes, the four gates do not align along perpendicular axes, and the scanty ruins within the city do not exhibit a radial or concentric street layout like the one at Ardashir Khwarrah. Near the north gate, remains of a water system supply, probably an aqueduct, are visible. The city center consists of a rocky outcrop featuring three peaks of varying sizes. At the highest peak, approximately 85 meters in height, lie the remains of an unexcavated citadel or arg largely built in mud-brick, which underwent enlargement and reinforcement at least three times. Several fortresses of Sasanian date or later are located in the surrounding mountains, protecting the round city. The majority of the surface pottery seems to be of Parthian or Sasanian date. Some of the shapes and surface treatments resemble those found at Qal’eh Dokhtar in Firūzabad, indicating an association with the early Sasanian period. Based on the ceramic finds, the main occupation at Dārābgird ended before the Ilkhanid period, c. 1250.

Archaeological Exploration

In modern times, it was Sir William Ouseley who brought the ruins of Dārābgird to the attention of Western scholars during his trip in 1811. Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste, who traveled in Iran between 1849 and 1850, published the first plan of the site. Their plan shows eight gates, with four strategically positioned at the cardinal points, and the remaining four evenly spaced between them. They also recorded and mapped the remains of an aqueduct or water supply system near the northern gateway. In the 1890s, Forsat Shirazi visited the ruins and described the site and its whereabouts. He published an engraving of the round city with a series of tents or temporary buildings near its center. Sir Aurel Stein’s thorough study of the ruins in 1934 marked a turning point in the archaeological exploration of Dārābgird. He gave a detailed description of the ruined city with the help of both historical accounts and his observations. He published a topographic plan of the round city, which has since been the most accurate plan of Dārābgird. In 2003, Peter H. Morgan conducted a survey at Dārābgird on behalf of the British Institute of Persian Studies. The site was the object of further surveys in 2009 by Sasan Seyedein, then an archaeology student at the University of Tehran.

Bibliography

Flandin, E. and P. Coste, Voyages en Perse, vol. 1, pl. 33.

Forsat Shirazi, M. N., Āsār-e Ajam, Bombay, 1314 H./1896, pp. 92-95, pl. 7 (for Dārābgird and the bas-relief).

Ghirshman, R., Bichapour, vol. 1, Paris, 1971, pp. 91-106 (for the bas-relief of Shapur).

Hermann, G., “The Darābgird Relief – Ardashir or Shapur?,” Iran, vol. 7, 1969, pp. 63-88.

Hinz, W., Altirasniche Funde und Forshungen, Berlin, 1969, pp. 145-171 (for the bas-relief of Shapur).

Karimian, H., and S. Seyedein, “A Preliminary Survey at the Circular City of Darabgird, Iran,” Antiquity, issue 324, vol. 84, 2010, pp. 1-5.

Karimian, H., and S. Seyedein, “Iranian Cities after the Collapse of Sasanian Kingdom: A Case Study of Darabgird,” International Journal of Humanities, vol. 18/2, 2011, pp. 51-62.

Morgan, P., “Some Remarks on a Preliminary Survey in Eastern Fars,” Iran, vol. 41, pp. 323-338.

Ouseley, W., Travels in Various Countries of the East, vol. 2, London, 1821 (pp. 129-136, pls. 33 and 35).

Schmidt, E. F., Persepolis, vol. 3, Chicago, 1970, pp. 127-128 (for the rock-relief of Shapur).

Shahbazi, A. Sh., “Some Remarks on the Sasanian relief at Darangird”, Summaries of Papers to be delivered at the Sixth International Congress of Iranian Art and Archaeology, Oxford, 1972, p. 76.

Stein, A., “An Archaeological Tour in the Ancient Persis,” Iraq, vol. 3, 1936, pp. 192-196 (for Dārābgird).

Trümpelmann, L. Das Sasanidische Felsrelief von Dārāb, Berlin, Iranische Denkmäler, vol. 6, Berlin, 1975.

Vanden Berghe, L., Reliefs rupestres de l’Iran ancien, Brussels, pp. 72-73, 129-130, pl. 22 (for the Dārābgird relief).

DOWNLOAD AS PDF

DOWNLOAD AS PDF