Name

Saint Stepanos/Qizil Vank/Qizil Kelisa سن استپانوس/قزل وانک/قزل کلیسا

Map

Historical Period

Islamic, Medieval

History and description

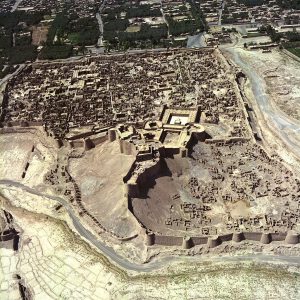

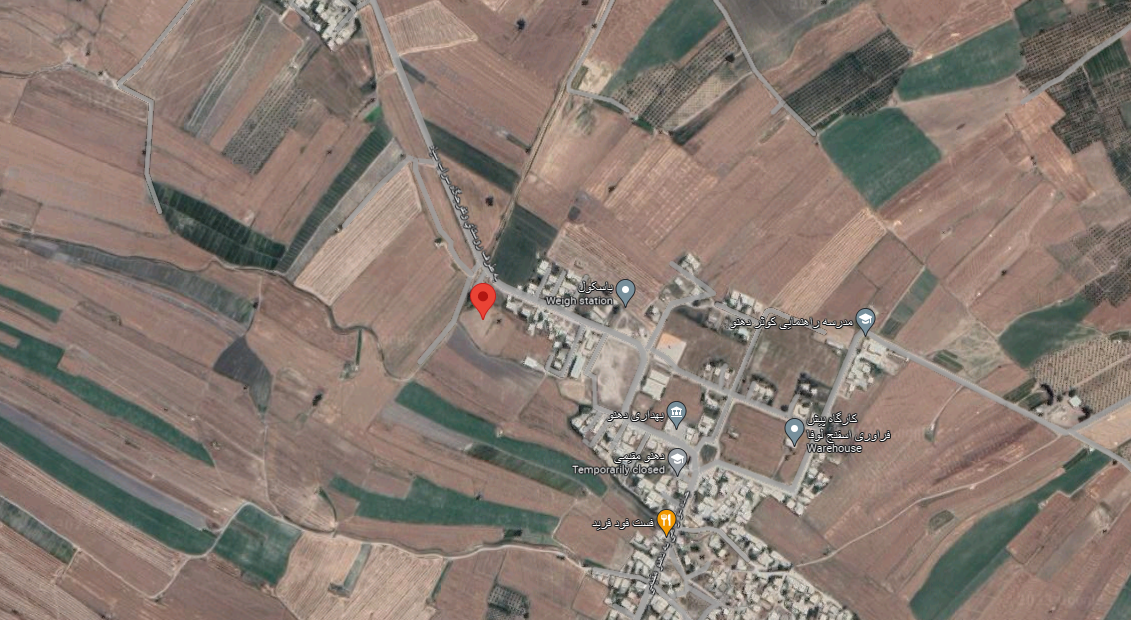

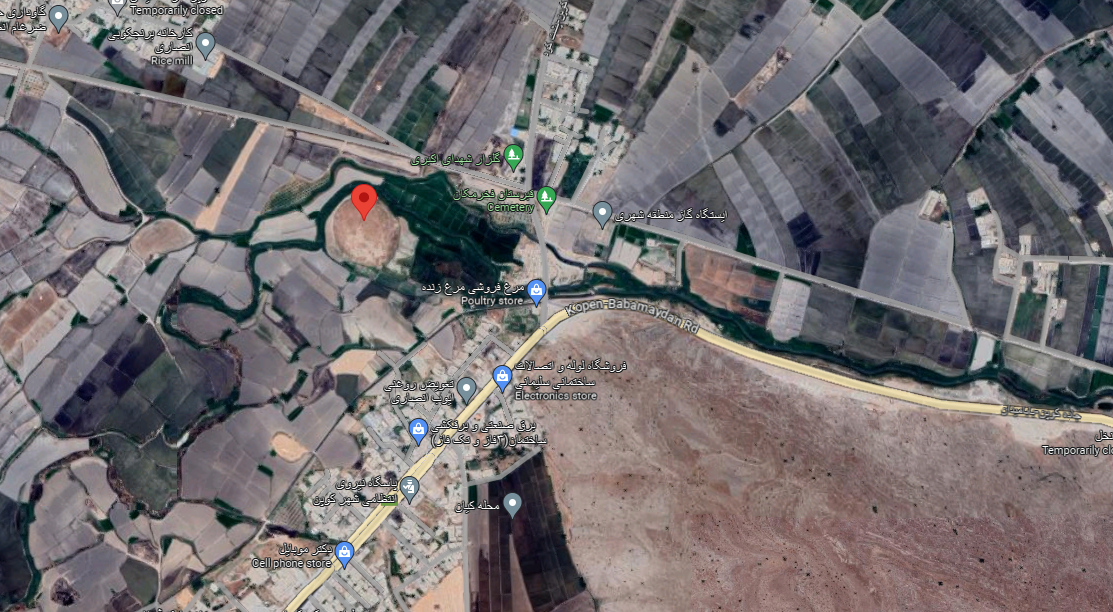

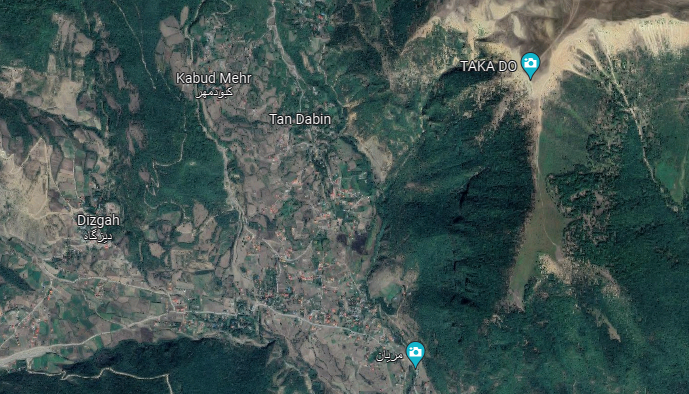

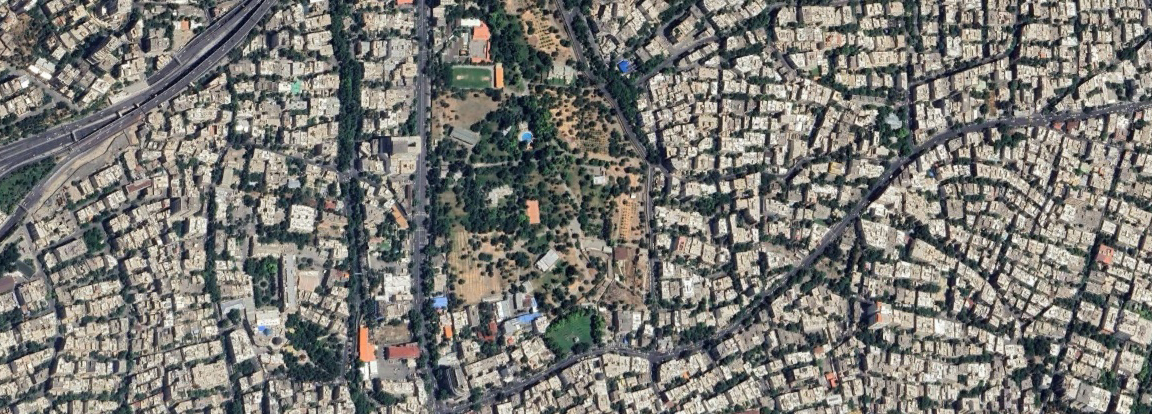

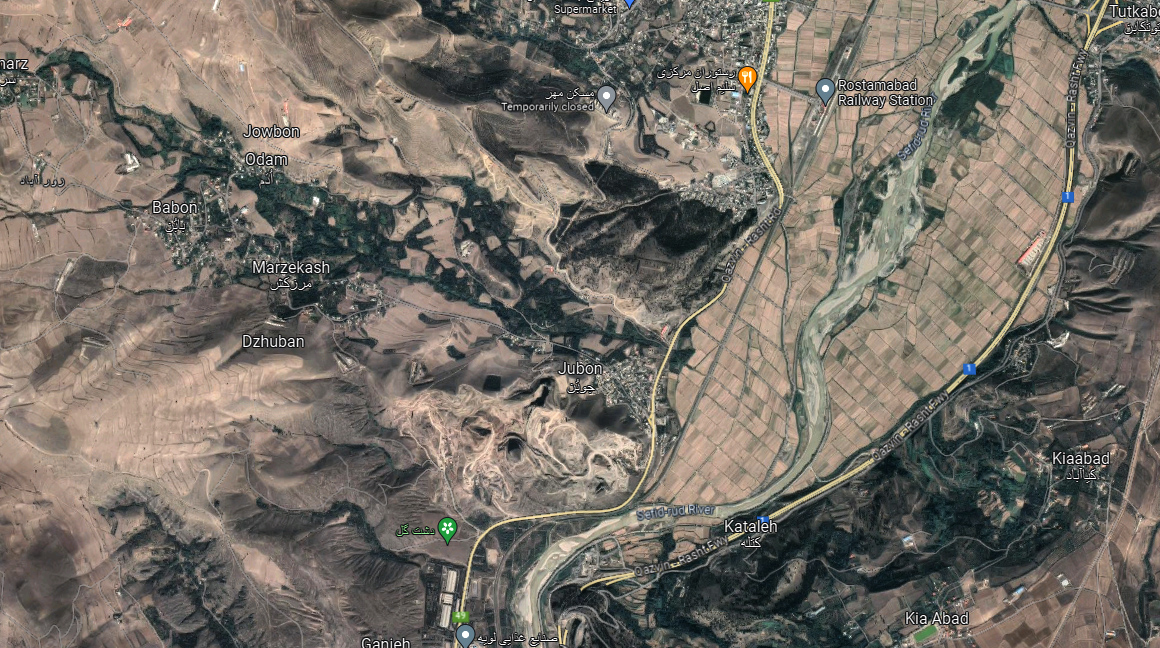

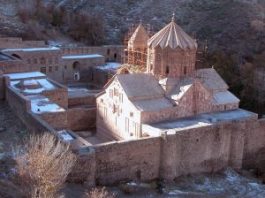

The St. Stepanos monastery is 15 km west of Jūlfa, 230 km northwest of Tabriz. The monastery is located at the end of a gorge that connects the Nakhjevan and Jūlfa plains, on the south side of the Araxes River (fig. 1). In the past, the monastery was also called the Maghart Monastery, named after the hill on which it was built; alternatively, it was known as the Dareshāmb Monastery, taking its name from a now-ruined village 3 km away at the confluence of the Ok-Tchai, a tributary of the Araxes.

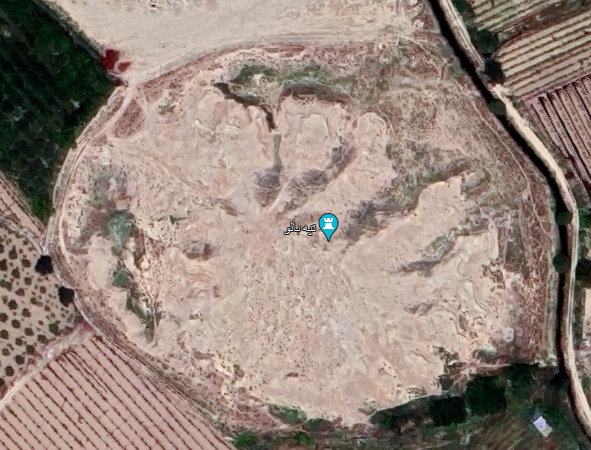

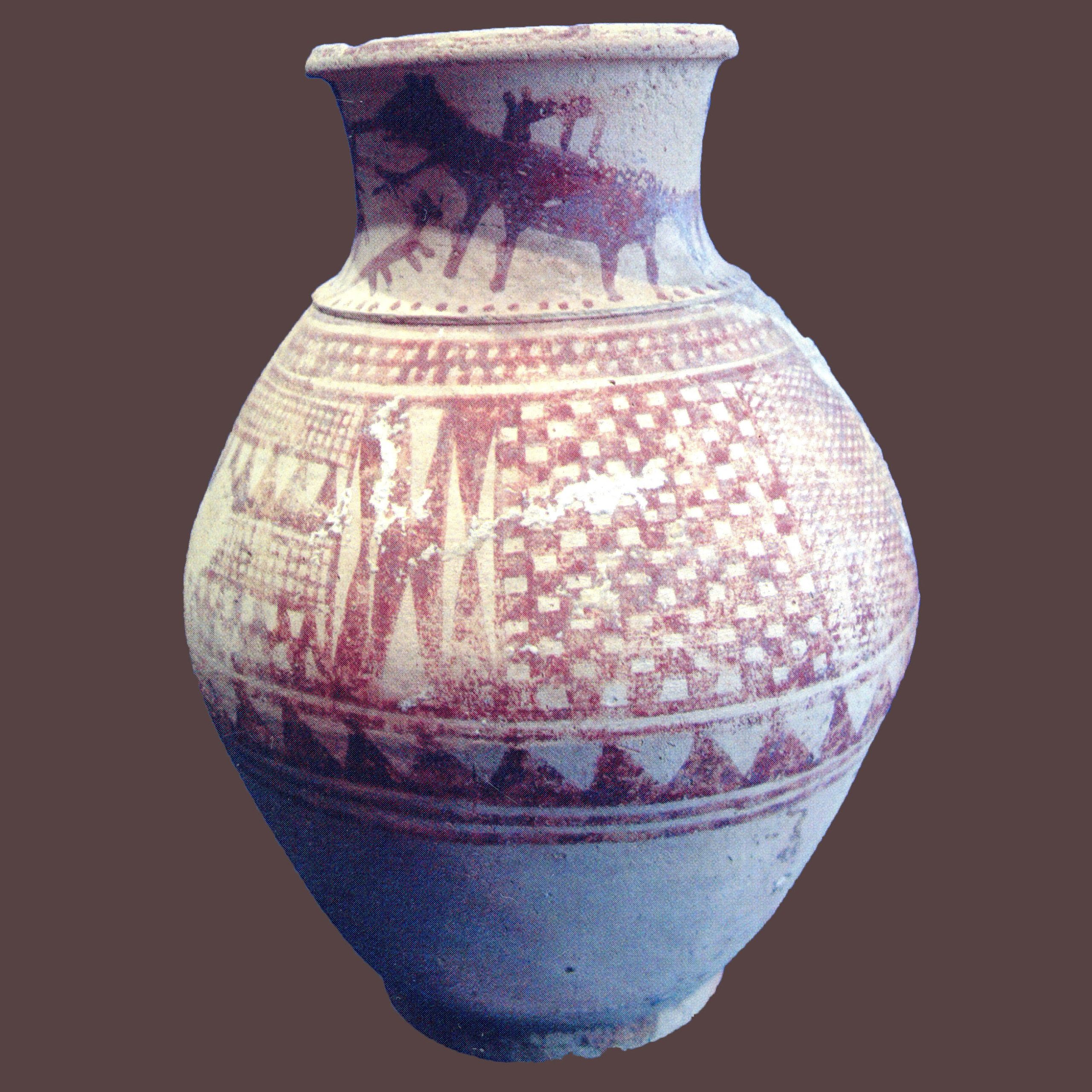

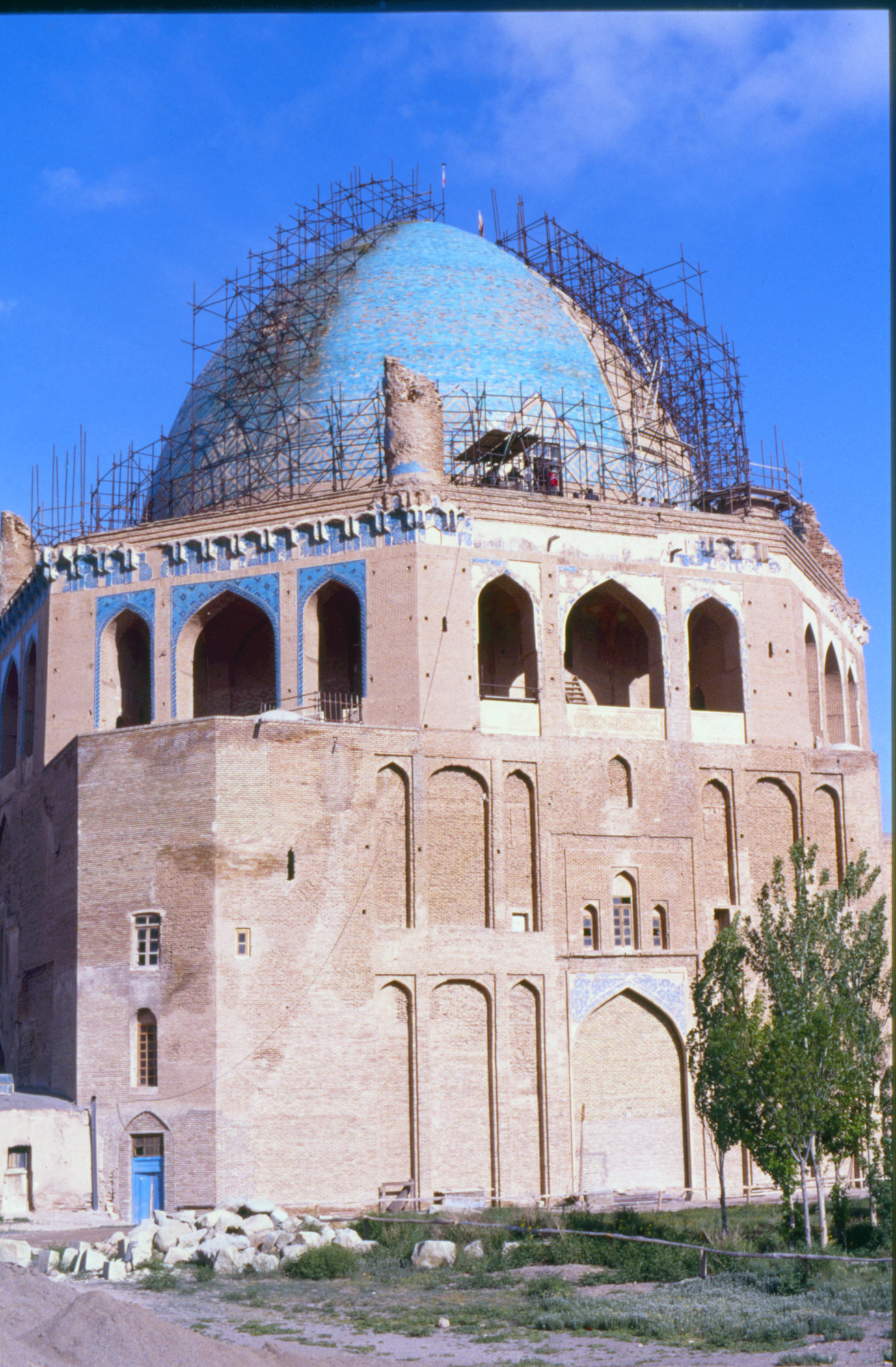

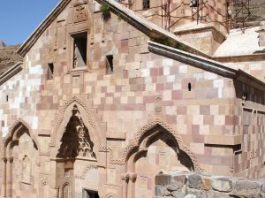

The monastery is built on terraces. It has a roughly rectangular plan, measuring 71 x 48 m (fig. 2). The material predominantly used for the construction of the monastery is a local red stone, hence the name of Qizil Kilisa (Red Church) given to it. The monastery is fortified with thick stone walls and circular and semicircular towers. The main entrance (fig. 3) set in a recess in the west wall is decorated with stalactites or muqarnases in the Saljuk style above the door and two side niches; there are inscriptions in Armenian and in Persian, the most important of which is the dedication plaque of Abbas Mirza in 1246/1826. There is a secondary entrance giving access to the cemetery that is located 100 m to the north on the mountain slope. The layout shows two distinct parts with a median sector. The northern area includes the main church and the small church, the southern area is occupied mostly with monks' cells, a refectory, and other auxiliary rooms organized around a courtyard.

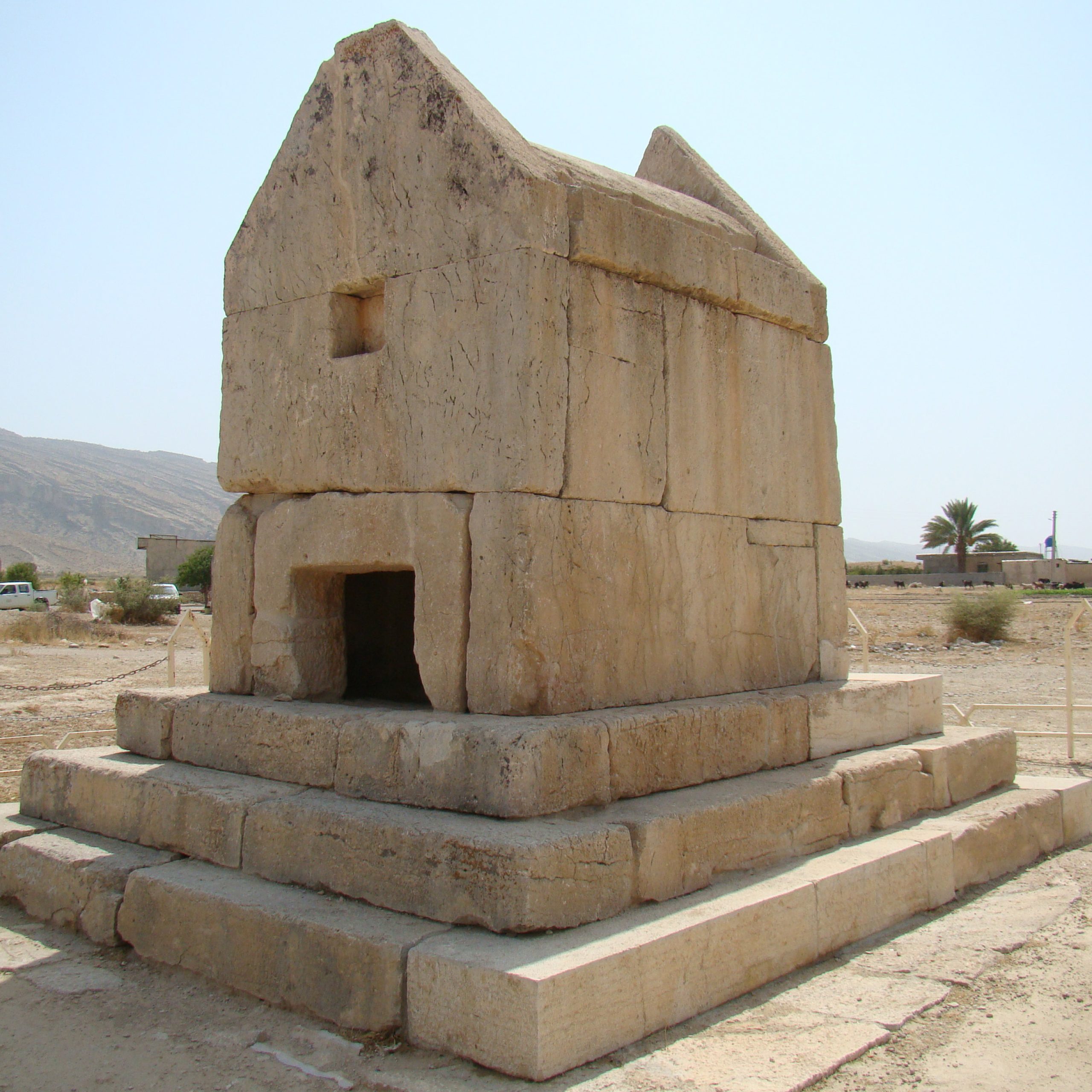

The northern wing is accessed through a bell tower. The main church is built at the center with a small church behind it along the north wall. The main church is 22.37 x 15.35 m. Its central dome stands on a 16-sided drum crowned by an “umbrella” roof (figs. 4-5). Half columns at the corners of the drum caped with dragon-shaped capitals. Bas-reliefs of apostles, saints, and seraphim, as well as crosses, stars, and birds, are added to decorate the drum. The interior has a cruciform plan with three polygonal apses. The north room on the ground floor served as the baptistery. In another room is a chapel, housing a model sarcophagus known as the Tomb of the Thousands. According to Armenian monastic tradition, the sarcophagus was intended to hold the relics of the thousand followers of Vartan, the Armenian hero who perished in the Battle of Avāvir in 451.

The small church (fig. 6), dedicated to Apostles Peter and Paul, includes a room known under the popular name of Ojāq-e Danial (Danial’s hearth /foyer) in Persian texts.

The main church’s west façade is decorated (fig. 7) with figures of the Virgin and Child, the Crucifixion, the Annunciation, the Resurrection, and a scene depicting the Stoning of St. Stepanos.

The south wing is organized around a courtyard and is surrounded by service rooms and other structures (fig. 8). On the east side, there is a passageway leading to the outside. The monks’ cells are located on the south side, facing west. On the south side of this wing, the abbot’s residence has its eyvān that opens onto the cloister. Adjacent to it is a reception hall with two storeys, facing the abbot’s residence. Moving south from this section, there is the monastery’s largest room which probably served as a refectory. Outside the monastery’s wall are stables and a water mill.

Stepanos (Stefan or Stephen), known as Nakhāvegā or the First Martyr, was one of the Seven to receive baptism from the Apostles. The saint set out to spread Christianity in the East; he was persecuted, stoned, and martyred in the whereabouts of the present-day monastery.

The monastery of St. Stepanos was, for a long time, the cultural center of the Armenians, where religious figures, calligraphers, painters, writers, and historians were pensioned. Several illuminated manuscripts produced or copied at St. Stepanos are now preserved in special collections libraries in Yerevan or Venice. The founding date of the monastery is uncertain, though most scholars suggest an origin in the seventh century. The oldest known document referring to the monastery dates to the year 649. Later, Armenian historical records indicate that in 976, Archbishop Khachik, the religious leader of Armenians, appointed Bishop Babgen to oversee the monastery. With the support of Ashūt Baghradūni, the ruler of Armenia, Bishop Babgen constructed a church at the site of the monastery site, possibly replacing the earlier St. Stepanos church. In 981, records indicate that Heripsimeh, the ruler’s daughter, acquired the village of Astāpāt and generously endowed the monastery with the village and its lands. The first recorded restoration work dates back to Ashut Baghraduni’s reign in 991. The monastery suffered during the Saljuk period, particularly during Alp Arsalan’s march against the Byzantines in 1150. The Mongol Ilkhāns of Persia adopted a favorable policy towards the Armenian population in their territories. In 1330, Ilkhān Abu-Said issued an order to establish and safeguard the boundaries of the monastery. In 1381, the St. Stepanos monastery was mentioned in the Narek manuscript as a prosperous cultural center.

Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid kingdom, took on a favorable policy towards the Armenians. He issued a decree forbidding any violation of the monastery and its lands. In 1604, during his war against the Ottomans, Shah Abbas decided to evacuate the region situated between the two empires, adopting a scorched land strategy. It seems that the St. Stepanos monastery like many other religious places in the region, had to be evacuated, though there are no records regarding its situation. After the war, in 1655, Hagup Jūyghatsi, the bishop of St. Stepanos, carried out renovations at the monastery. Furthermore, records indicate that between 1682 and 1691, repairs were regularly made to the monastery’s structures. It was during this time that Jean-Baptist Tavernier, the French traveler, visited and stayed at the St. Stepanos monastery. Tavernier gave a vivid account of the monastery, part of it reads as follows:

St. Stephen is a Covent built not above 30 Years ago. It stands upon the Mountains, in a barren place, and of difficult access. But the reason why the Armenians chose that place before any other, is because that St. Bartholomew and St. Matthew retir'd thither in the time of their Persecution. They add, that St. Matthew did a Miracle in that place: for that there being no Water there before, he only strook his Stick upon the Ground, and presently there arose a Spring. This Spring is about half a quarter of a League from the Covent, under a Vault with a good Door to it, to keep the Water from being wasted. The Armenians go to visit this Spring in great Devotion, having laid the Water into the Covent with Pipes. They also say, that in this place they found several Relics which St. Bartholomew and St. Matthew left there, to which they add a great many others; among the rest a Cross, made of the Basin wherein Christ wash'd his Disciples Feet: In the middle of the Cross is a white Stone, which, as they report, if you lay upon a Sick person, will turn black if the person be likely to dye; and recover its former whiteness after the death of the party. A Jaw-Bone of St. Stephen the Martyr. The Scull of St. Matthew. A Bone of the Neck, and a Bone of the Finger of St. John Baptist. A Hand of St. Gregory, who was the Disciple of Dionysius the Areopagite. A little Box, wherein they keep a great number of pieces of Bones, which they believe to be the Relics of the Seventy-Two Disciples.

Ali Khan Vali, the governor of the Urmia region in the 19th century, mentions that Danial’s bones were kept within a confined space in this part of the monastery. It is not clear if the bones belonged to Daniel, the Biblical figure, or they were remains of a certain St. Daniel, a native of Syria in the fifth century. Thanks to the efforts of Shahryar Adle, the box containing the bones was eventually rediscovered hidden in the upper storey of the church, between the cupola and the vaulted roof in 2004. The remains were transferred to the Armenian Diocese in Tabriz.

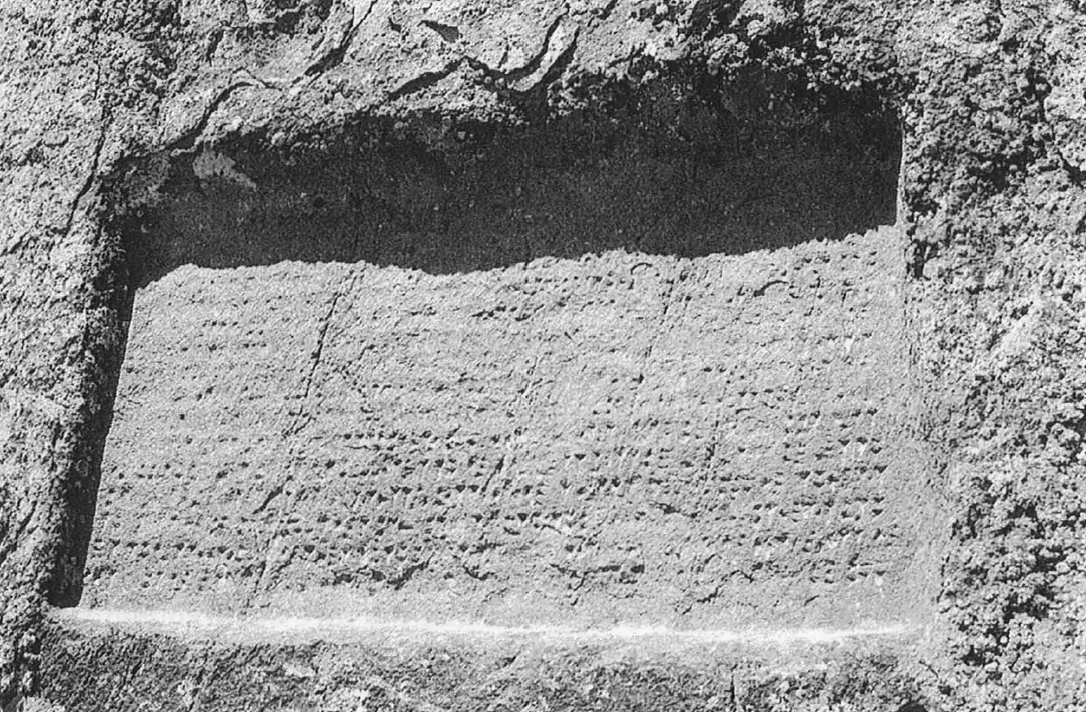

Information about St. Stepanos becomes scarce following the decline of the Safavids in the early 18th century. The most noteworthy reference to the monastery occurred much later, in 1826, during the Russo-Persian wars. An inscription, commissioned by Crown Prince Abbas Mirza, was placed on the entrance, stating that the prince acquired the monastery’s land (part of the adjacent village of Darresham) and donated it to the monastery. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, the monastery underwent multiple repairs and gained recognition as a National Monument of Iran in 1955.

Archaeological Exploration

During the 1960s, Wolfram Kleiss from the German Archaeological Institute conducted a survey of the monastery and published the first plan of its structures. Careful study of the monument was undertaken by Hartmut Hofrichter in 1971 in the framework of his doctoral dissertation at the University of Aachen. In 1977, with the support of the Armenian community, significant restoration work was performed at the St. Stepanos monastery sponsored by Iran’s National Office of Protection and Restoration of Historical Monuments. Thanks to the efforts of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization and Shahryar Adle, the St. Stepanos monastery was inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO in 2008.

Bibliography

Hofrichter, H., “Das Kloster Sdepannos Nachawega in der Iranischen Provinz Aserbaidschan,” Revue des Études arméniennes, nouvelle série, vol. 9, 1972, pp. 193-239.

Hofrichter, H., “The St. Stephen Monastery,” St. Stephanos, Documents of Armenian Architecture, vol. 20, Milan, 1989, pp. 5-9, 48-65.

Karang, A. and J. Torabi Tabatabai, “Kelisāy-e San Stepanos,” Barressihā-ye Tārikhi, vol. 9, No. 1, 1353/1974, pp. 1-20.

Kleiss, W., “Das armenische Kloster des Heiligen Stephanos in Iranisch-Azerbaidjan,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen, vol. 18, 1968, pp. 270-285.

Tavernier, J.-B., The Six Travels of John Baptista Tavernier, London, 1678, pp. 17-18.

Uluhogian, G., “Votive Inscriptions at the Monastery of St. Stephen the Protomartyr,” St. Stephanos, Documents of Armenian Architecture, vol. 20, Milan, 1989, pp. 10-17.

DOWNLOAD AS PDF

DOWNLOAD AS PDF