Name

Bardak Siāh, Borāzjān بردک سیاه، برازجان

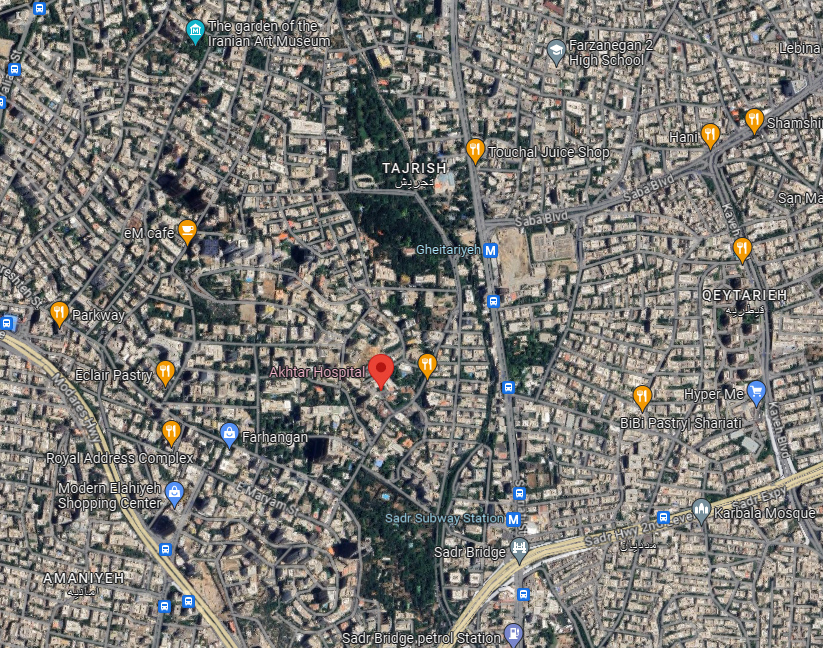

Map

Historical Period

Achaemenid

History and description:

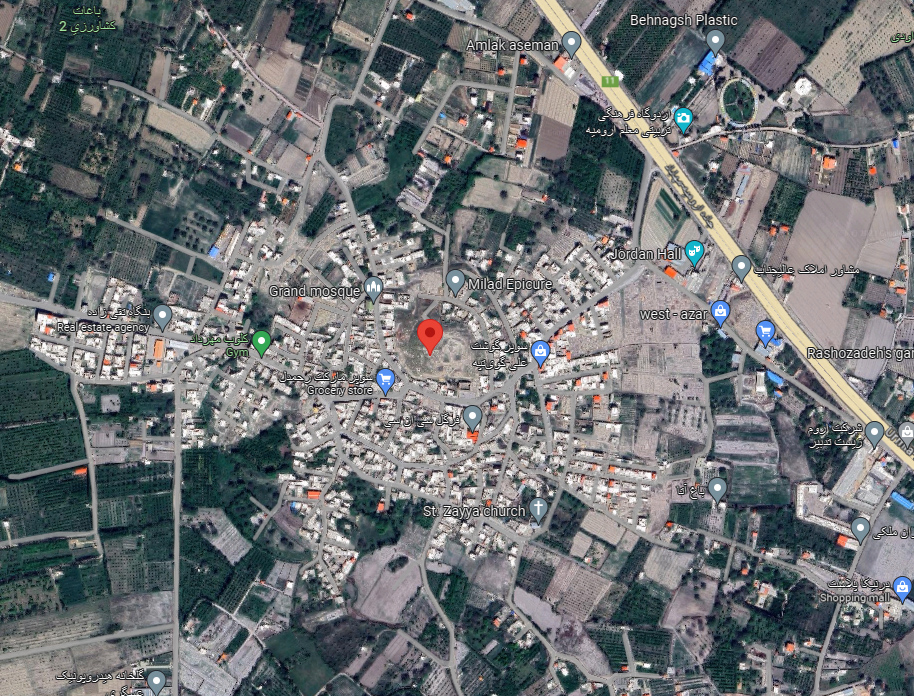

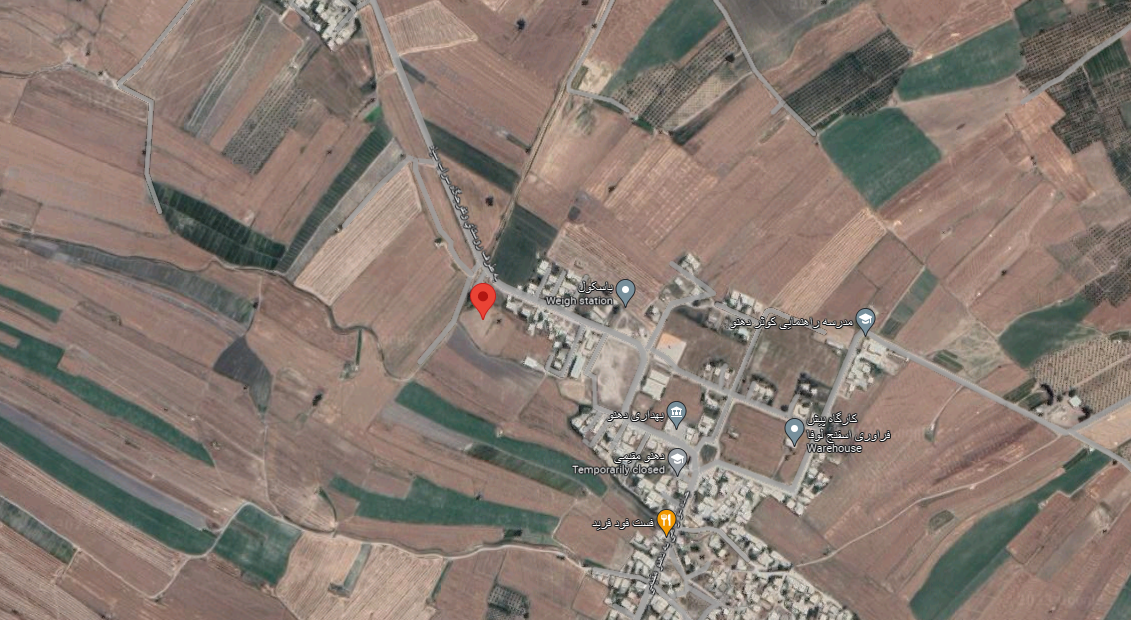

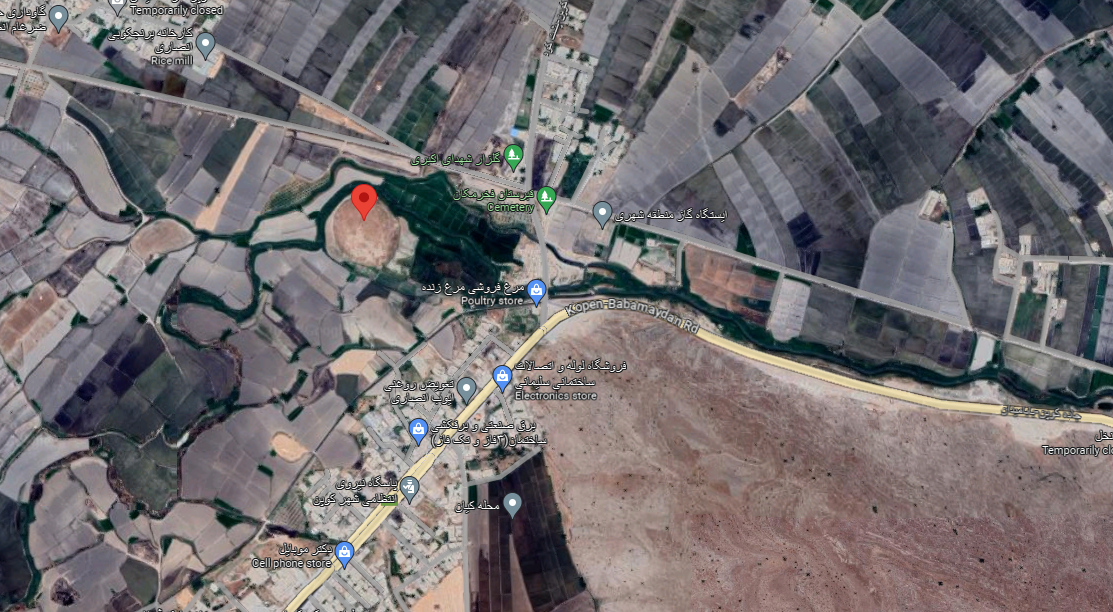

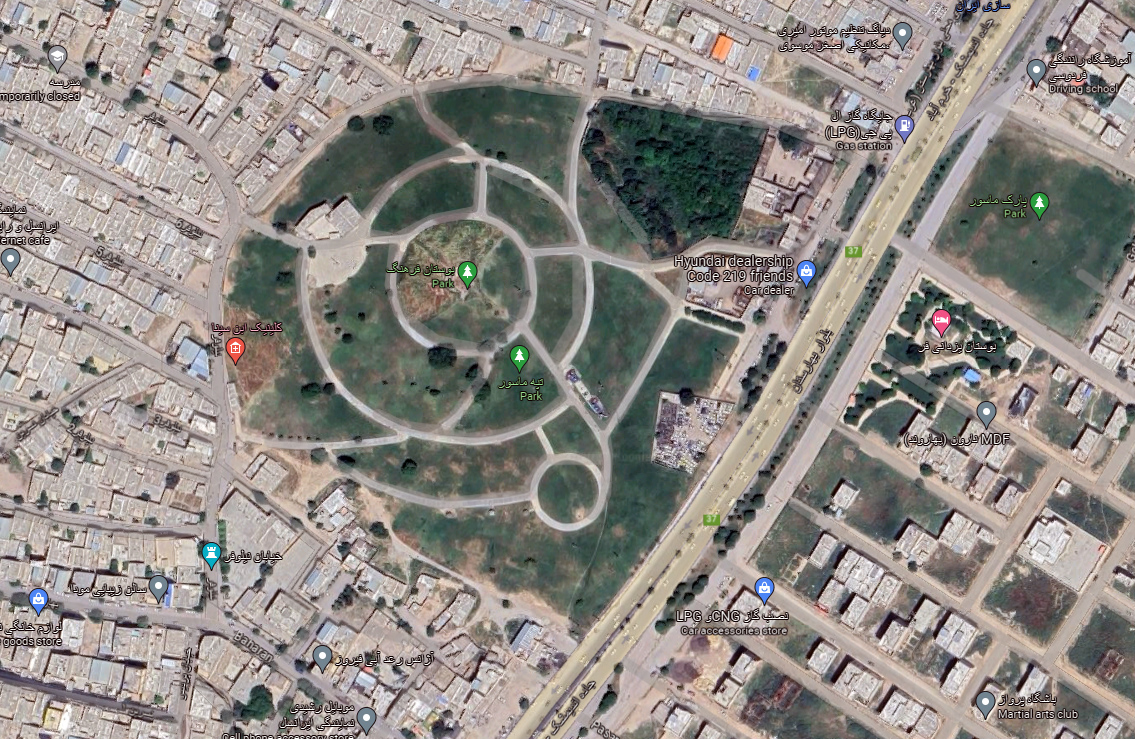

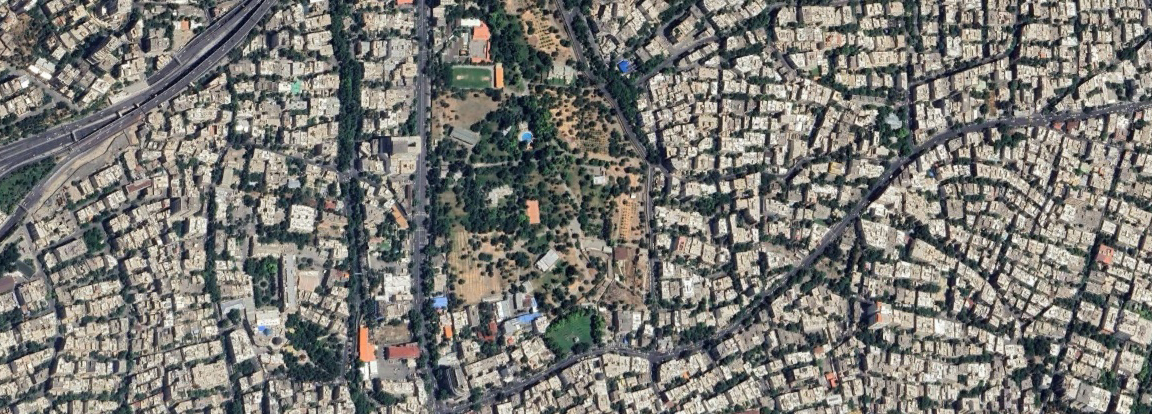

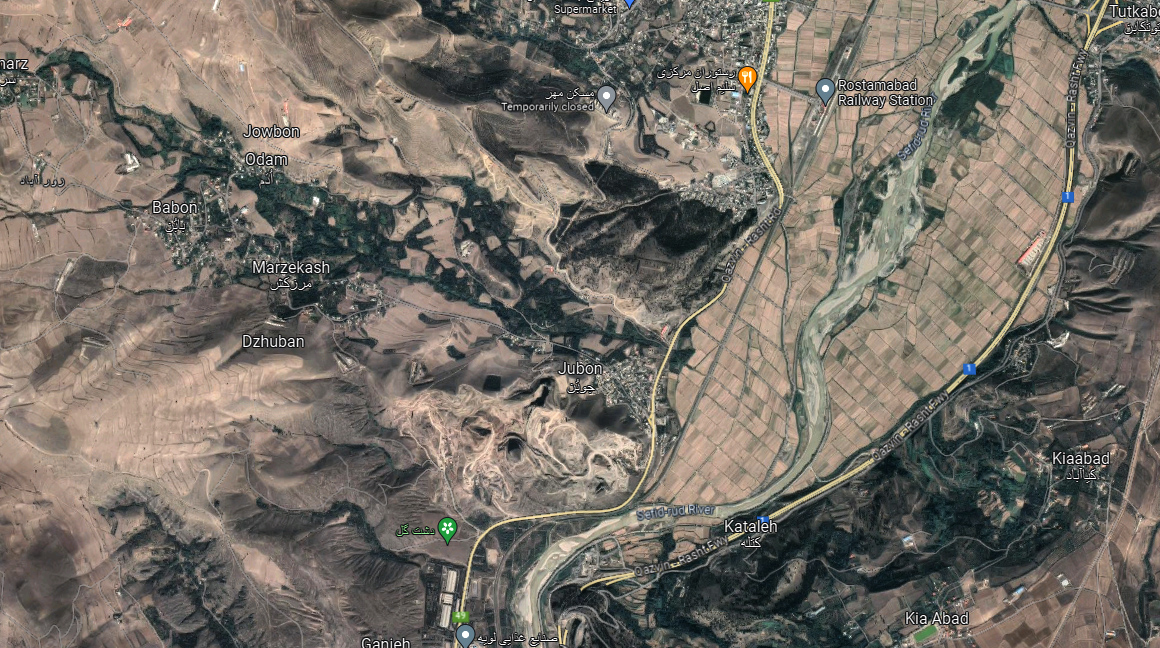

Bardak-e Siāh lies 2 km north of the village of Dorūdgāh in the Borāzjān plain. The area is referred to under the names Taḫmâka/Tamūkkan/Taocê/Tūz/Tūj/Tūzag/Tawwaj. The toponyms are different variations of a single geographical name. During the Achaemenid period, the toponym Taḫmâka/Tamūkkan/Taocê is found in three types of texts: late Babylonian sources, the Persepolis Fortification Archive (PFA), and Greek sources, with minor variations among them. The toponym refers to a coastal region that was an Achaemenid majestic center and thanks to the archaeology, we are aware of three palatial monuments in the Borāzjān delta called Bardak-e Siāh, Charkhāb, and Sang-e Siāh. As a confirmation, the Persepolis Fortification Archive (PFA) records thousand of workers and skilled artisans from Egypt, Lycia, Cappadocia, and Skudria who were active in the building programs in Borāzjān. It is uncertain whether the toponym Taḫmâka/Tamūkkan/Taocê refers to the entire plain or one of the Achaemenid structures in the area. Esmail Yaghmaee, the excavator of Bardak-e Siāh, suggests that the site is the location of ancient Tamūkkan mentioned in the PFA.

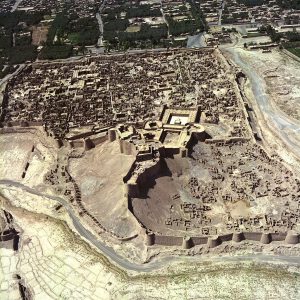

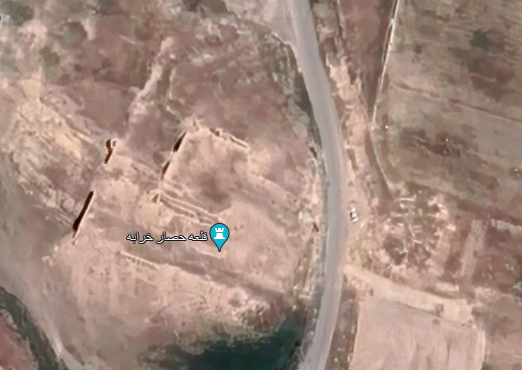

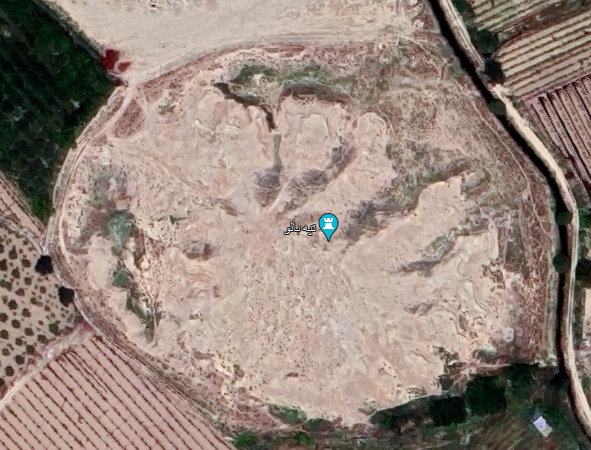

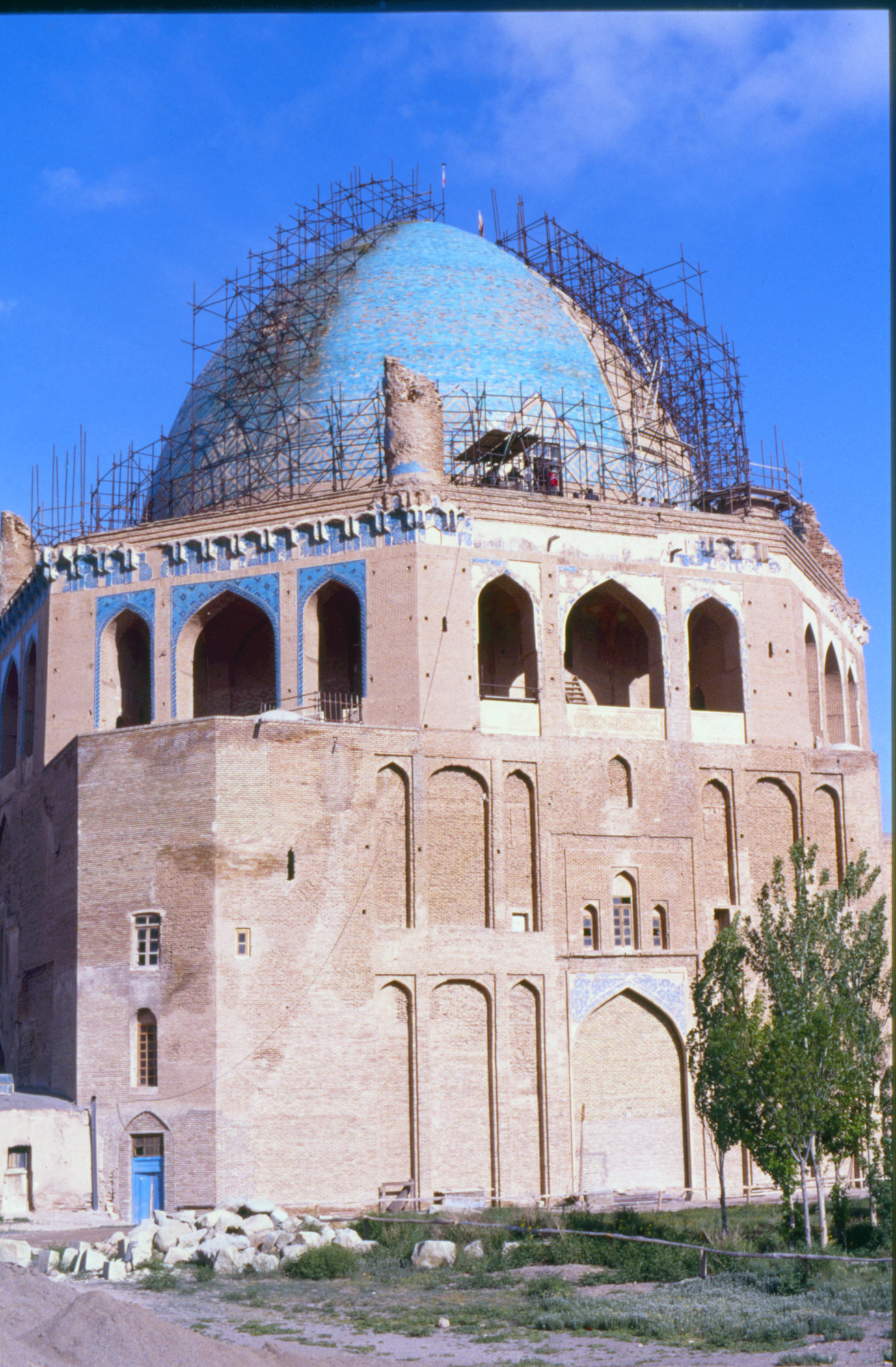

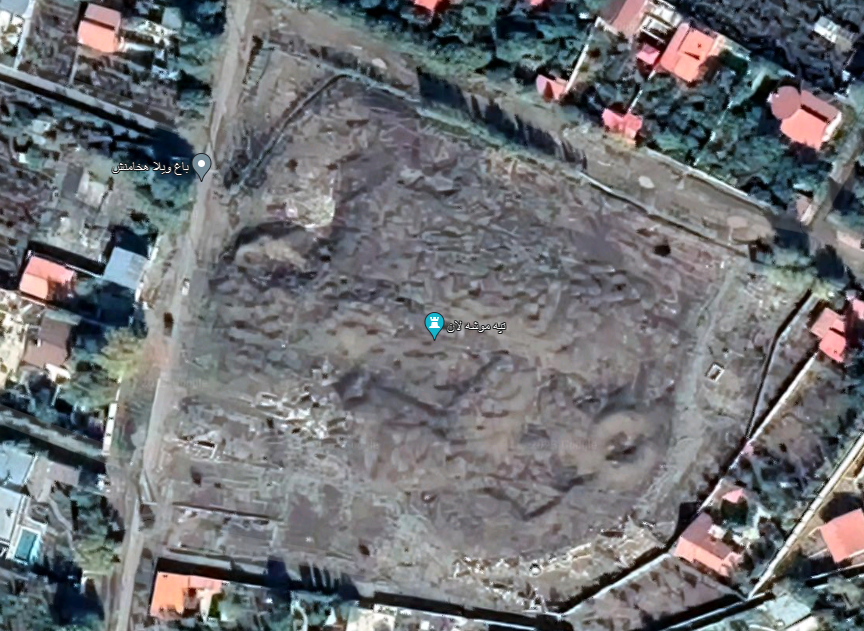

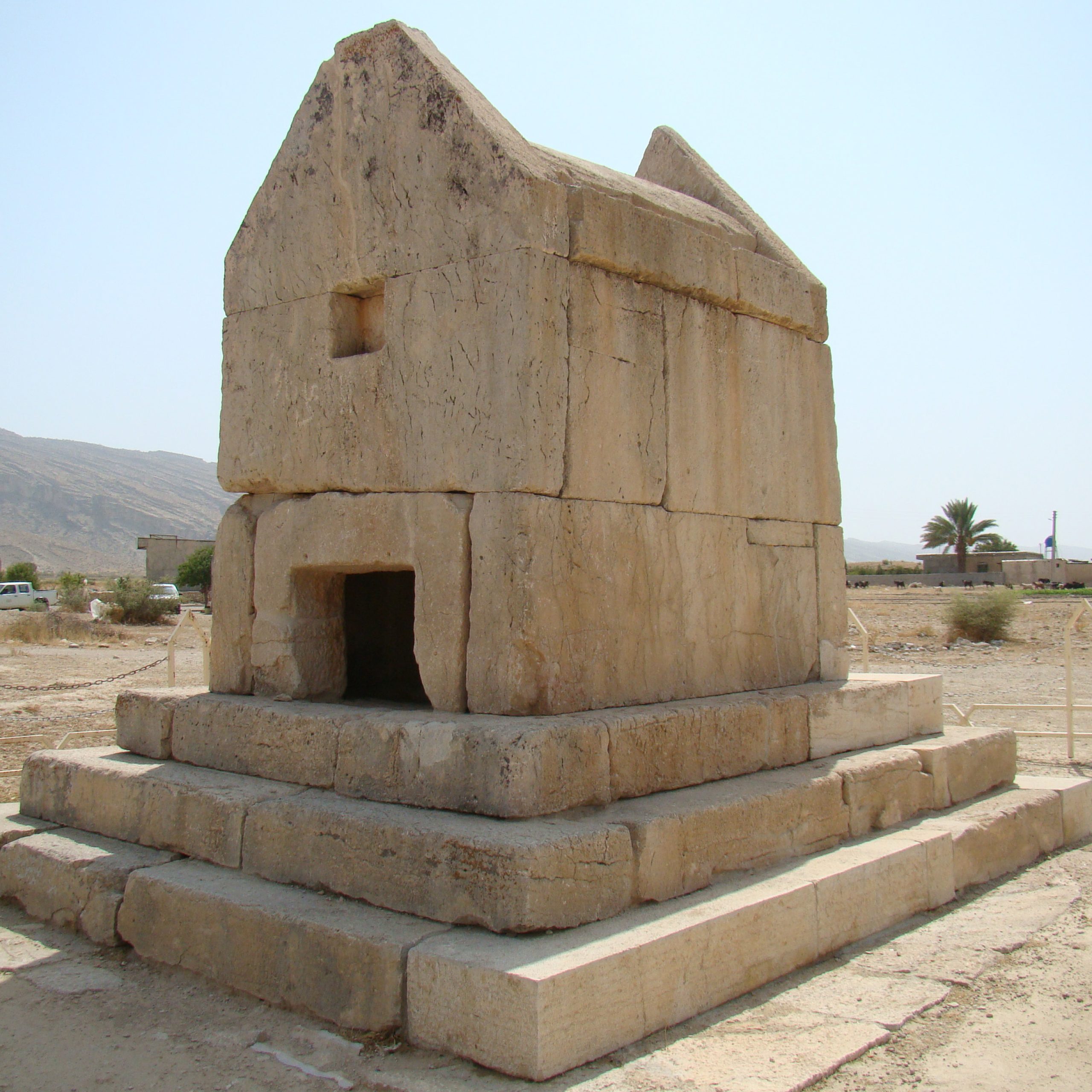

Two parts of the monument have so far been uncovered: the main hall and parts of the southern portico. The main excavated building is a columned hall, 22 x 18.5 m, covering an area of 403 square meters (fig. 1). The hall has 24 columns, of which the column bases in stone have survived; the shafts and capitals were probably in perishable wood (fig. 2). The column bases, 80 cm high, consist of three parts, from bottom to top: a black section, two white sections, and a white grooved torus that measures 84 cm in diameter and 18 cm in height. The main hall is accessed using four paved doorways. To the south of the main hall, there is an L-shaped columned portico (fig. 3); as the excavation of this area is incomplete, future exploration may change the plan of the portico. Near the southern doorway, a fragmentary relief in black stone was found (see below). The excavation of the structure was left unfinished, so the entirety of its plan is currently unknown. The excavator suggested two different dates for the monument; he assumed that the monument was built during the reign of Cyrus I while the relief (below) was made during the reign of Darius I. There is no evidence of column shafts, floor, and ceiling; the excavator, however, observed traces of a pale green plaster. The site is situated in a palm grove and suffers from poor drainage of the ground.

Archaeological Exploration

Two seasons of excavations were carried out at Bardak Siāh by Esmail Yaghmaee on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research in the winter of 1977 and in 2004-2005. A geophysical survey was later carried out by Kourosh Mohammadkhani in 2014.

Finds

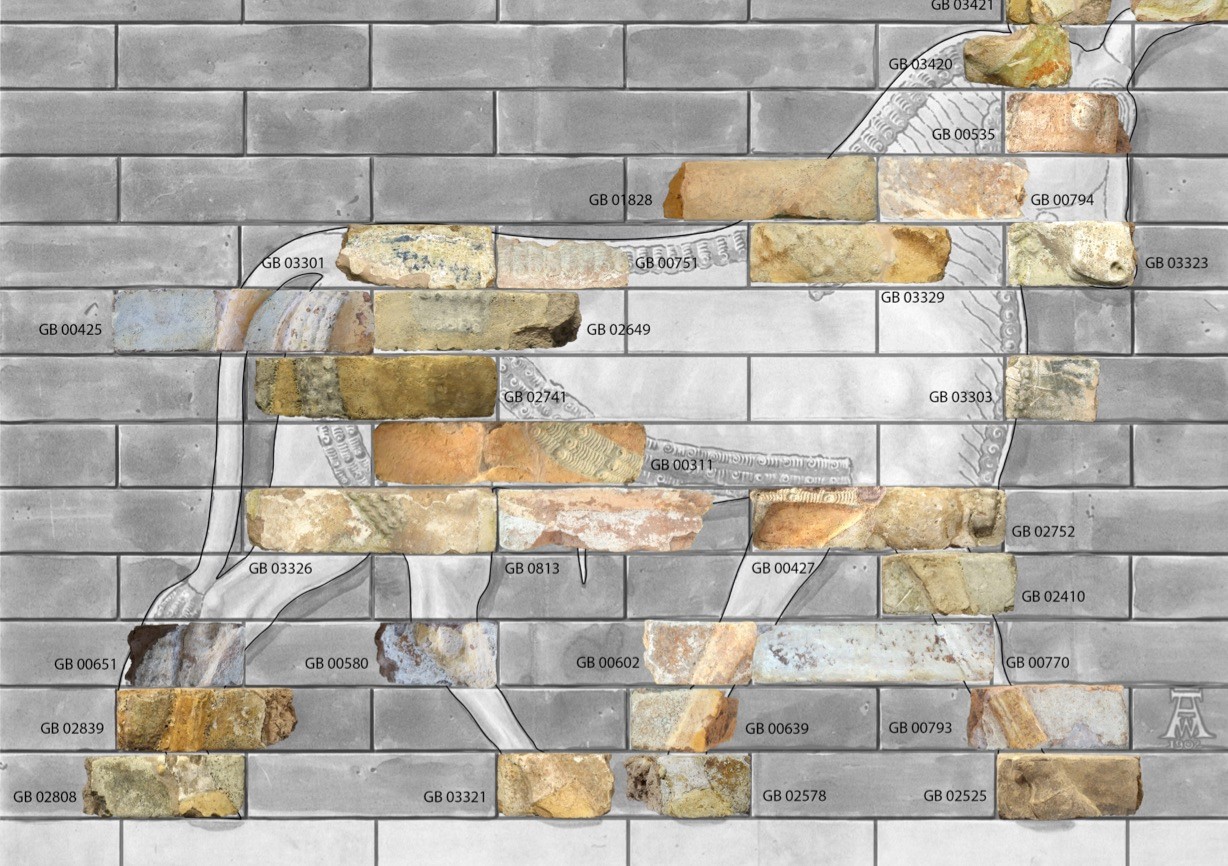

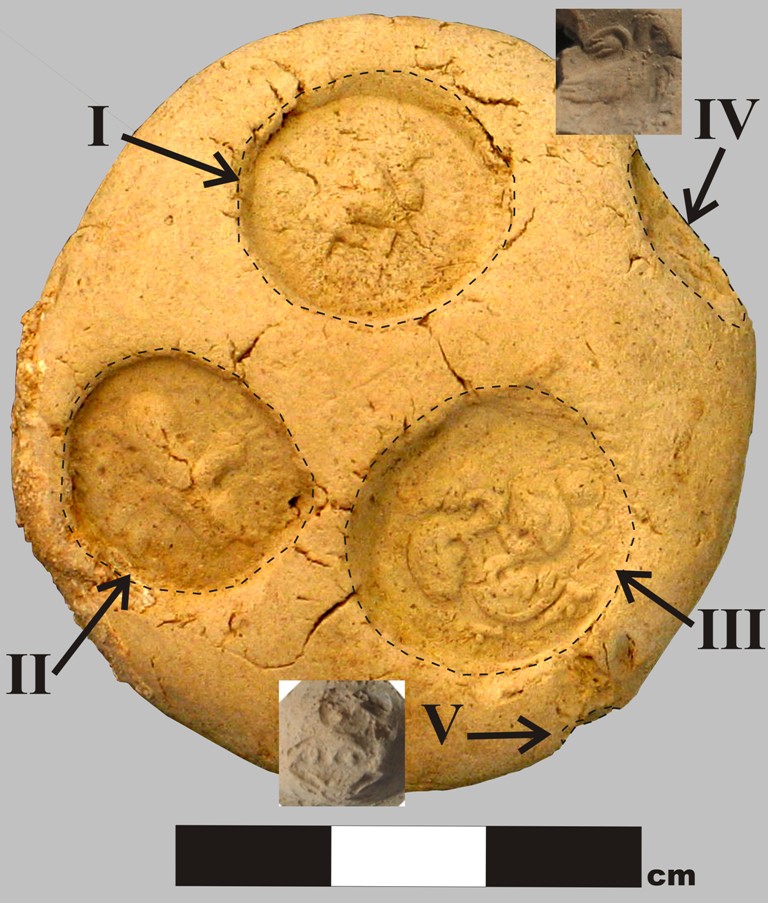

Excavated finds consist of fragments of stone sculptures, plaques of precious metal, pottery, bones, and inscribed fragments in stone. The most important discovery is, indeed, a large decorated fragment in black stone of a bas-relief. The fragment, 153 cm high and 55 cm wide, was found on its left side near the southern doorway of the main hall (Yaghmaei, Kākh-e Bardak Siāh, pp. 89-90). The surviving bas-relief depicts the head of a king with a parasol entering or exiting the palace (figs. 4 and 5). The style is Persepolitan and this led the excavator to conclude that there was a pair of such decorated jambs on either side of the south doorway representing King Darius I.

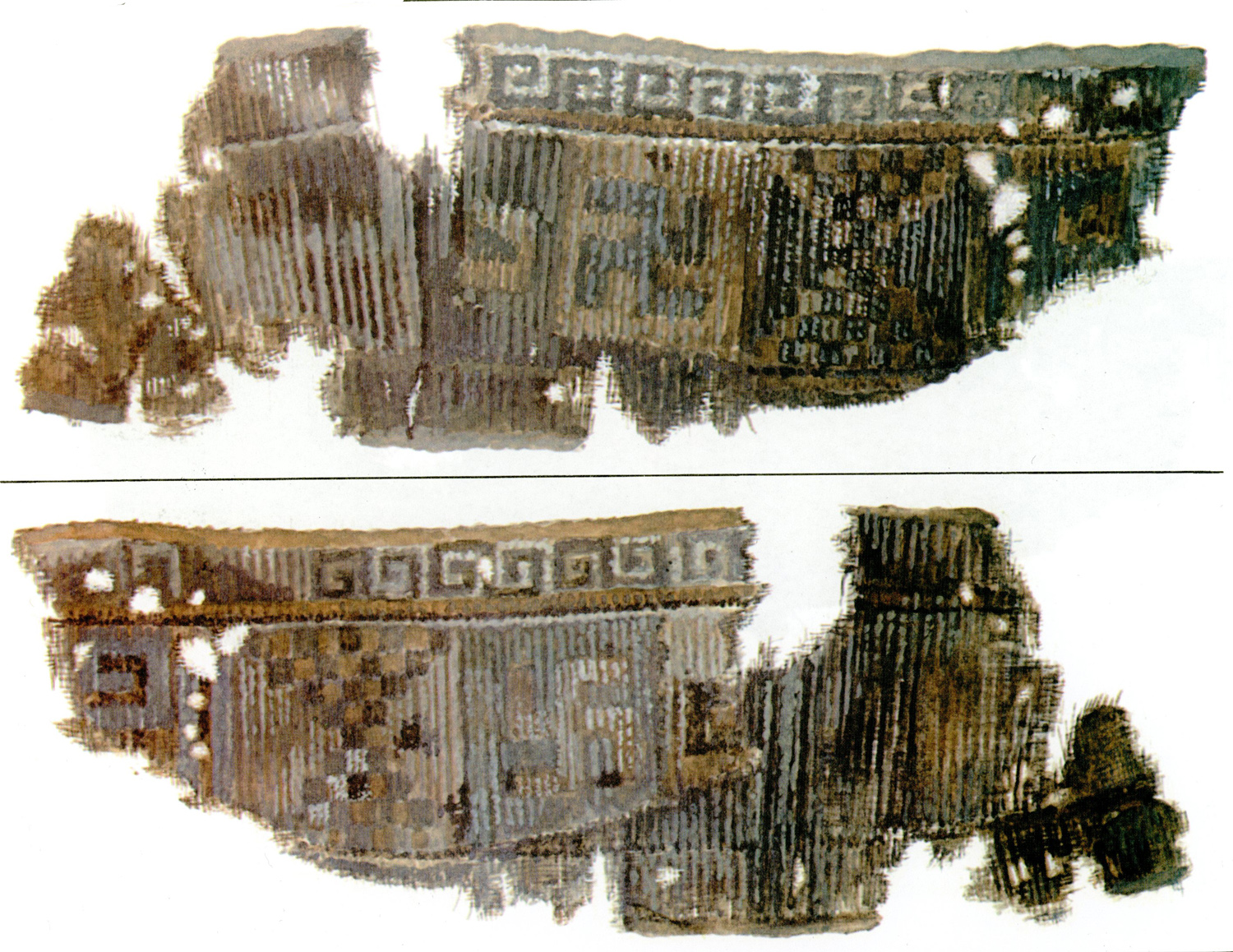

A total of 3100 grams of gold plaques was found in the excavation of the main hall (Yaghmaei, Kākh-e Bardak Siāh, pp. 74-75); the plaques had been folded and concealed near one of the best-preserved column bases – base K (figs. 6 and 7). Yaghamaei speculates the plaques were used as decorations for the hall or to cover bas-reliefs on the walls before being folded and hidden under the column base by the Macedonians, who never had a chance to retrieve them. (Yaghmaei, Kākh-e Bardak Siāh, p. 317).

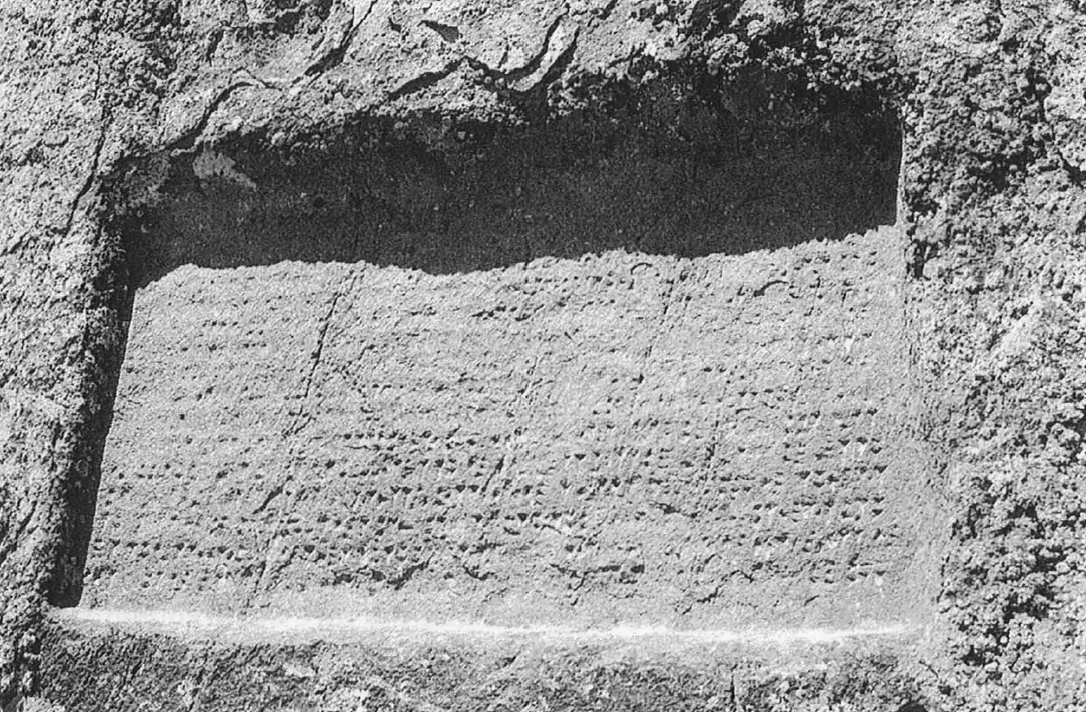

Three fragmentary inscribed stones were also discovered in the ruins of the main hall (fig. 8). The longest is just a short line in Babylonian (Yaghmaei, Kakh-e Bardak Siāh, pp. 115-119).

Fragmentary sculptures found at Bardak Siāh show that there were decorated areas with bas-reliefs (Yaghmaei, Kākh-e Bardak Siāh, pp. 95-113).

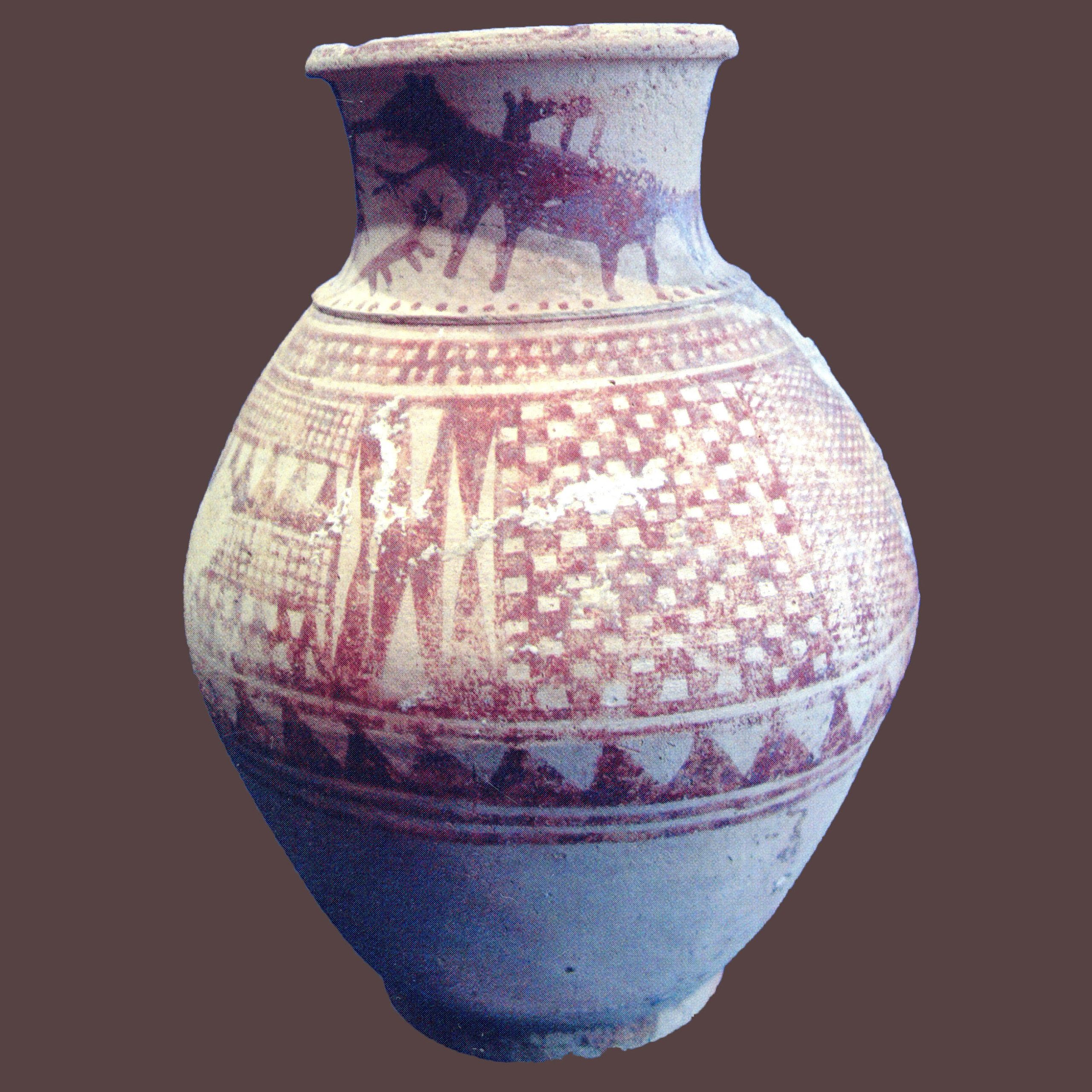

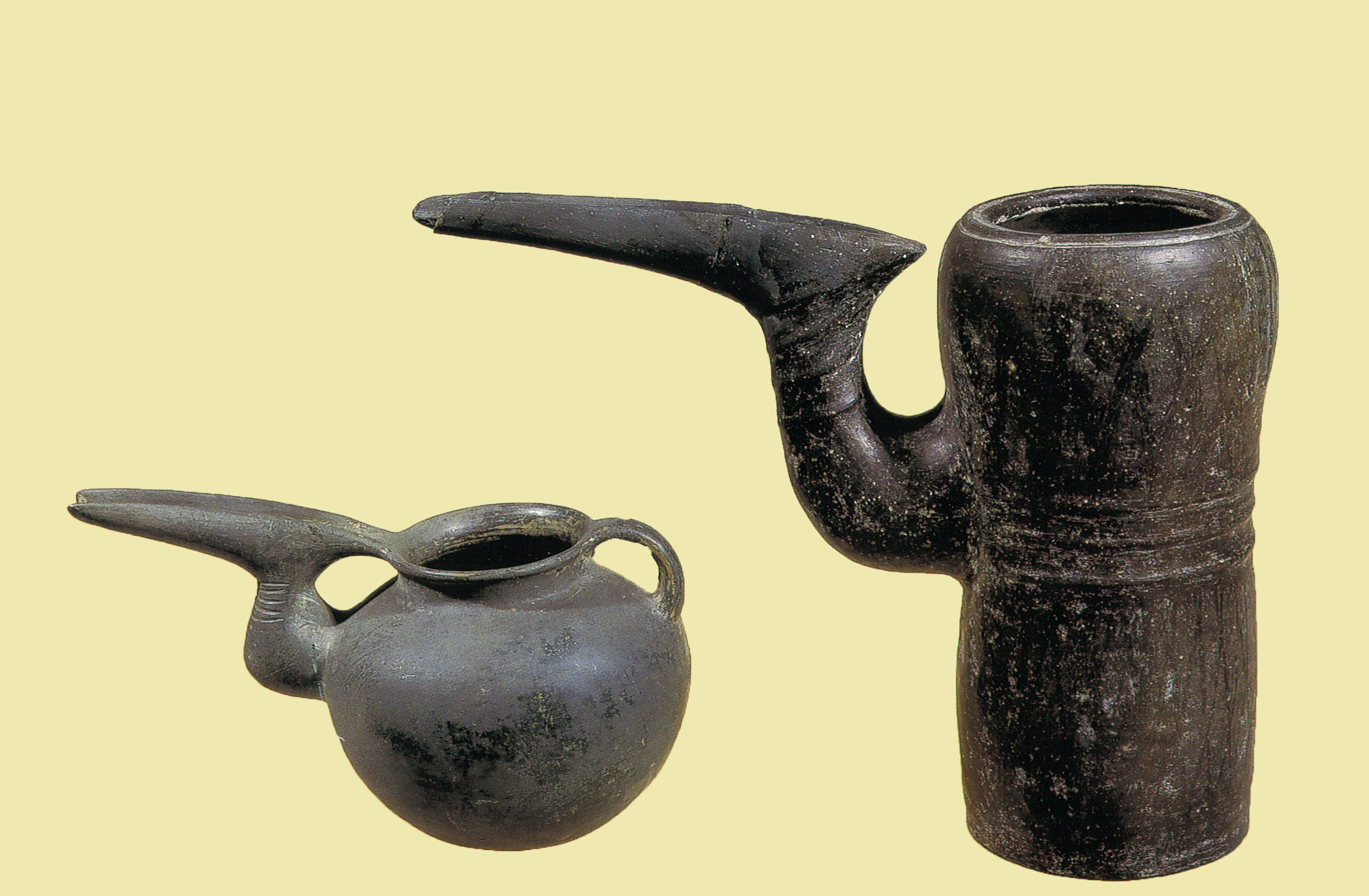

Achaemenid potsherds resemble those found in the Pasargadae excavations (Yaghmaei, Kākh-e Bardak Siāh, pp. 154-164).

Bibliography

Ebrahimi, N., “Gozāresh-e kāvosh-hā-ye bāstānshenāsi-ye dar mohit-e peirāmuni-ye kākh-hā-ye hakhāmaneshi-ye Charkhāb, Sang-e Siyāh va Bardak-e Siyāh dar Borāzjān bar asās-e natāyej-e barresi-hā-ye geophizik,” Gozāresh-hā-ye hevdahomin gerdehamāee-ye sālāne-ye bāstānshenāsi-ye Irān, vol. 17/1, R. Shirazi and Sh. Hurshid (eds.), Tehran, 1398/2019. pp. 30-37 (in Persian).

Henkelman, W. F. M., “From Gabae to Taoce: The Geography of the Central Administrative Province,” P. Briant, W.F.M. Henkelman, M.W. Stolper (eds.), L’archive des Fortifications de Persépolis. État des questions et perspectives de recherches. Persika 12, Paris, 2008, pp. 303-316.

Karimian, H., A. A. Sarfaraz, N. Ebrahimi, “Bāz-yābi-ye kākh-hā-ye hakhāmaneshi dar Borāzjān bā etekā be dāde-hā-ye bāstānshenāsi”, Bāgh-e Nazar, vol. 14, 1389/2010, pp. 45-58 (in Persian).

Karimian, H., A. A. Sarfaraz, and N. Ebrahimi, “Persian Splendour: Ancient Palaces in Iran,” Current World Archaeology, vol. 49, 2011, pp. 42-49.

Potts, D.T., “They Went to Tamukkan: Some Observations on Bushehr, Borazjan and Overland Travel Between the Persian Gulf and the Achaemenid Capitals. Parseh,” Journal of Archaeological Studies, vol. 6, 2022, 14-38.

Tolini, G., “Les travailleurs babyloniens et le palais de Taokè,” ARTA 2008.002.

Yaghmaee, E. and S. Imeni, Sang-e Siyāh, kākhi ke digar nist: kāvosh-hā-ye bāstānshenāsi dar Dashtestān, Borāzjān, roustā-ye Jatut, Tehran, Karnamak publication, 1400/2022 (In Persian with English abstract).

Yaghmaee, E., “Excavations in Dashtestan (Borazjan, Iran) (Abstract)”, J. Curtis and St John Simpson (eds.), The World of Achaemenid Persia History: Art and Society in Iran and the Ancient Near East, Proceedings of a conference at the British Museum 29th September–1st October 2005, 2010, p. 317.

Yaghmaee, E., “Yāfte-hā-ye hāsel az kāvosh-hā-ye mohavateh-ye Dorūdgāh-e kākh-e Bardak-e Siyāh, Būshehr”, Gozide’i az yāfteha-ye pazhūheshā-ye bāstānshenasi-ye Iran dar sāl-e 1394, 2017, pp. 87-94 (in Persian with an English abstract).

Yaghmaei, E., Kākh-e Bardak Siāh. Dashtestān, Borāzjān, Tehran, 1397/2018 (in Persian with an abstract in English).

Zehbari, Z., “The Borazjan Monuments: A Synthesis of Past and Recent Works,” ARTA 2020.002. http://www.achemenet.com/pdf/arta/ARTA_2020_002_Zehbari.pdf .

Zehbari, Z. “On the Participation of Egyptian Artists in Achaemenid Art”, C. W. Hess and F. Manuelli (eds.), Bridging the Gap: Disciplines, Times, and spaces in Dialogue, Sessions 1, 2, and 5 from the Conference Broadening Horizons 6 Held at the Freie Universität Berlin, 24–28 June 2019, 2021, pp. 59- 79. https://www.archaeopress.com/Archaeopress/Products/9781803270944).

DOWNLOAD AS PDF

DOWNLOAD AS PDF