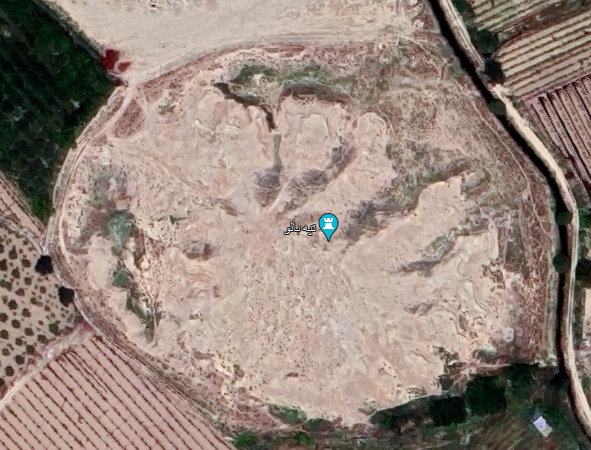

Tōmb-e Bōtتمب بت

Location: The region of Mohr, the Province of Fars

27°44’16.34″N 52°39’7.44″E

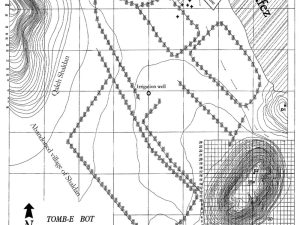

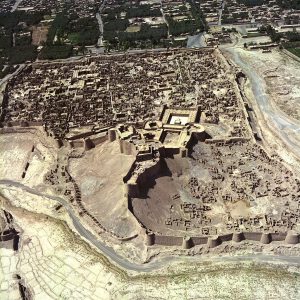

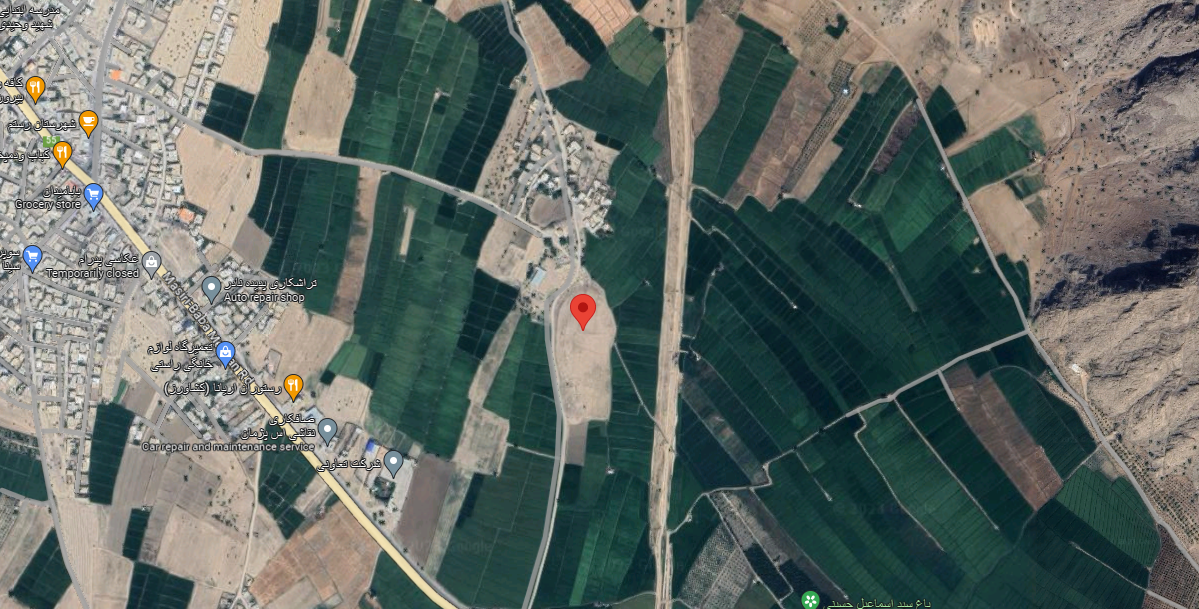

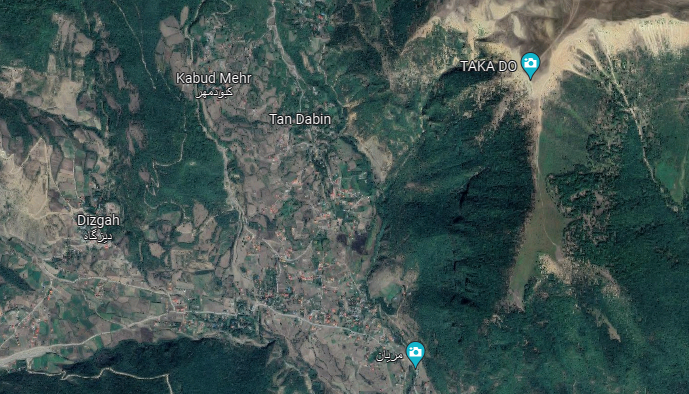

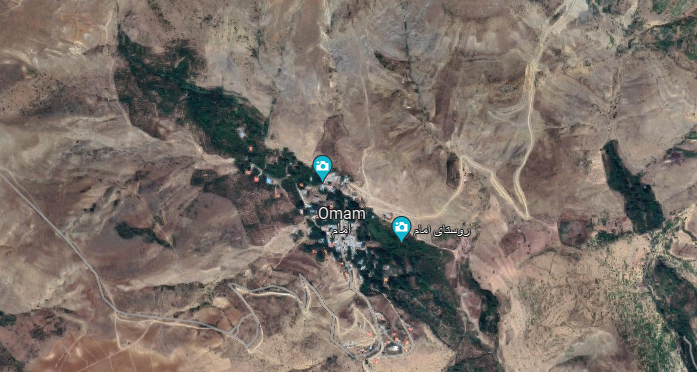

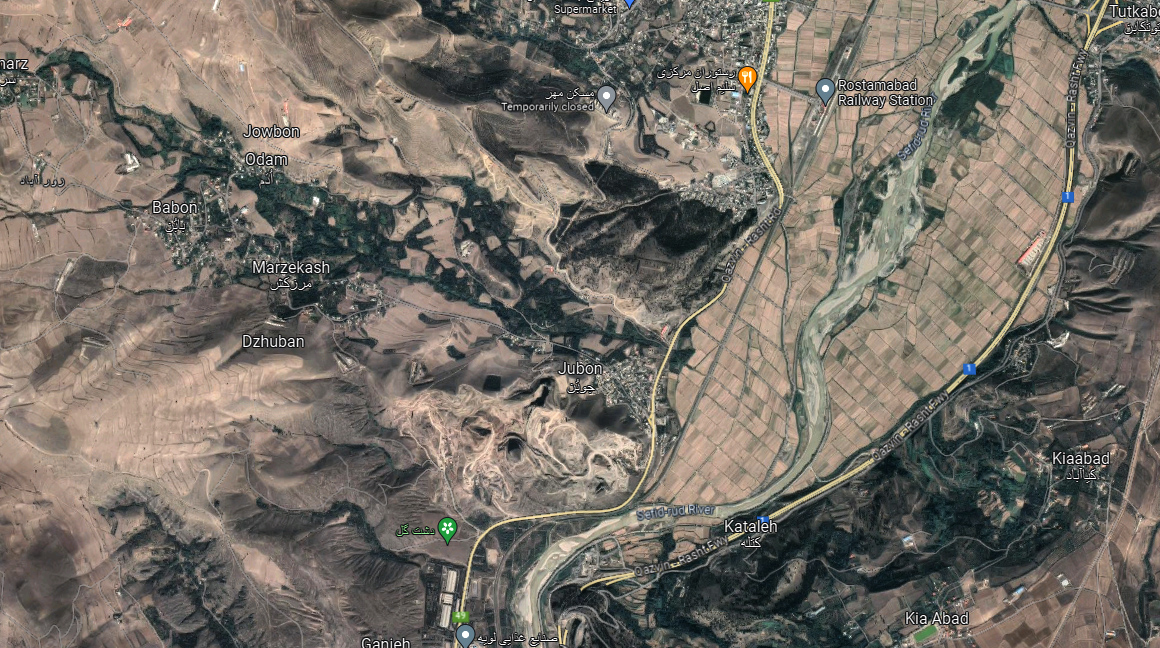

Situated in the valley of the Mehran River, some 40 km north of the port of Sirāf, Tōmb-e Bōt lies at the northern extremity of a defile that stretches for 120 km northwest-southeast and is approximately 10 km wide, at an elevation of 500 meters above sea level.

Location:

Historical Period:

Post-Achaemenid to Late Parthian (c. 300 B.C. – 224 A.D.)

History and Description:

The site does not figure in any ancient or medieval sources. The region, however, is mentioned in Fārsnāme-ye Nāseri as part of the Gallehdār District where, despite the existence of a seasonal river, water was scarce and the inhabitants relied on dry farming and limited livestock (Fasa’i, Fārsnāme-ye Nāseri, vol. 2, p. 1457). Because of its proximity to the coast of the Persian Gulf, the region seems to be a refuge for petty kings and minor rulers who continued to rule over the country in the years that followed the demise of the Achaemenid Empire. As early as 1911, the British traveler and officer, Arnāold Wilson, crossed the hinterland behind the coast and wrote (Wilson, S. W. Persia, p. 184):

Each valley was a social unit with its own leaders and headman, its own reserves of grain and its own ancient traditions. Civilization here is of extreme antiquity. Almost every valley has its mounds, probably older than Babylon, its own pre-Islamic rock tombs and inscriptions and its own bit of paved roads, inherited probably from Sasanian times.

As Donald Whitcomb rightly points out, the ruins encountered in the region “rarely measures up to this romantic account,” but they are testimonies to the extensive archaeological remains and the complex patterns of social organization and economic history of the country (Whitcomb, “Archaeological Surveys in the Highlands Behind Siraf,” p. 97).

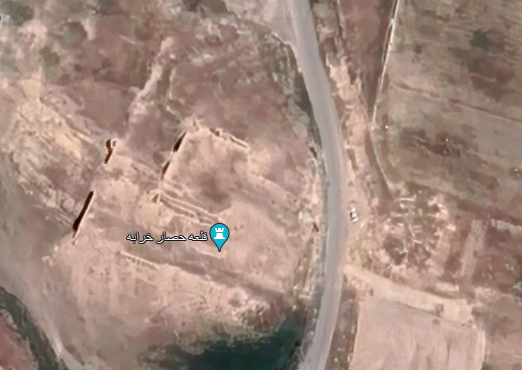

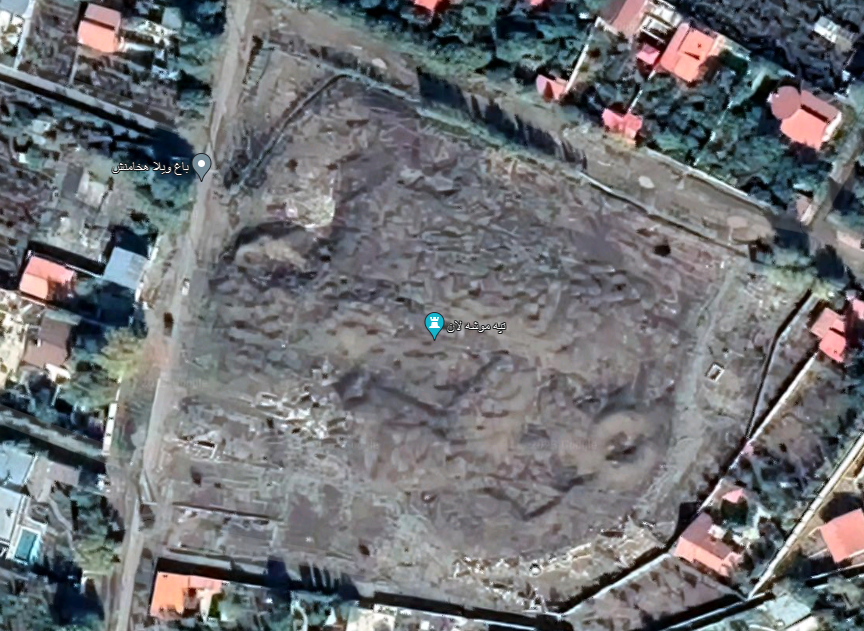

The remains are located a few hundred meters to the north of the abandoned village of Shaldān or Shaldūn that once had a small fortress known as Qal’eh Shaldān. Tōmb-e Bōt means “mound of idols”, and indeed the name refers to an archaeological mound with fragmentary architectural vestiges and sculptures. Tōmb-e Bōt covers a total area of 5 to 7 hectares together with the adjoining, at least, three mounds to the east and southwest of a field where farming activities in the past two decades yielded sculptured fragments (fig. 1, fig. 2). The aforementioned field receives its water from a nearby well, which provides potable water. Because of its arable soil, the territory sustains a small community of farmers to live there throughout the year.

Archaeological Exploration:

In the winter of 1932-33, Aurel Stein traveled in the region and surveyed sites around the village of Gallehdār (Stein, Archaeological Reconnaissances, pp. 212-214). Had he gone 7 km further north he might have seen the fragments at Tomb-e Bot. It is also possible that the stone fragments were discovered after Stein visited the region. Another group of 21 sites was registered during a later survey program by Heinz Gaube (Gaube, “Im Hinterland von Siraf,” pp. 142-166). Finally, in the 1999-2000 fieldwork season, Alireza Askari Chaverdi identified 43 more sites, raising the number of recorded sites in the area to 76 (Askari Chaverdi and Azarnoush, “Survey of Archaeological Sites of the Persian Gulf Hinterland: Lāmerd and Mohr, Fars,”). The remains at Tōmb-e Bōt were discovered during an archaeological survey conducted by the author on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research between 1998 and 2000 (Askari Chaverdi, “Fars after Darius III”; “Recent Post-Achaemenid Finds from Southern Fars, Iran,”).

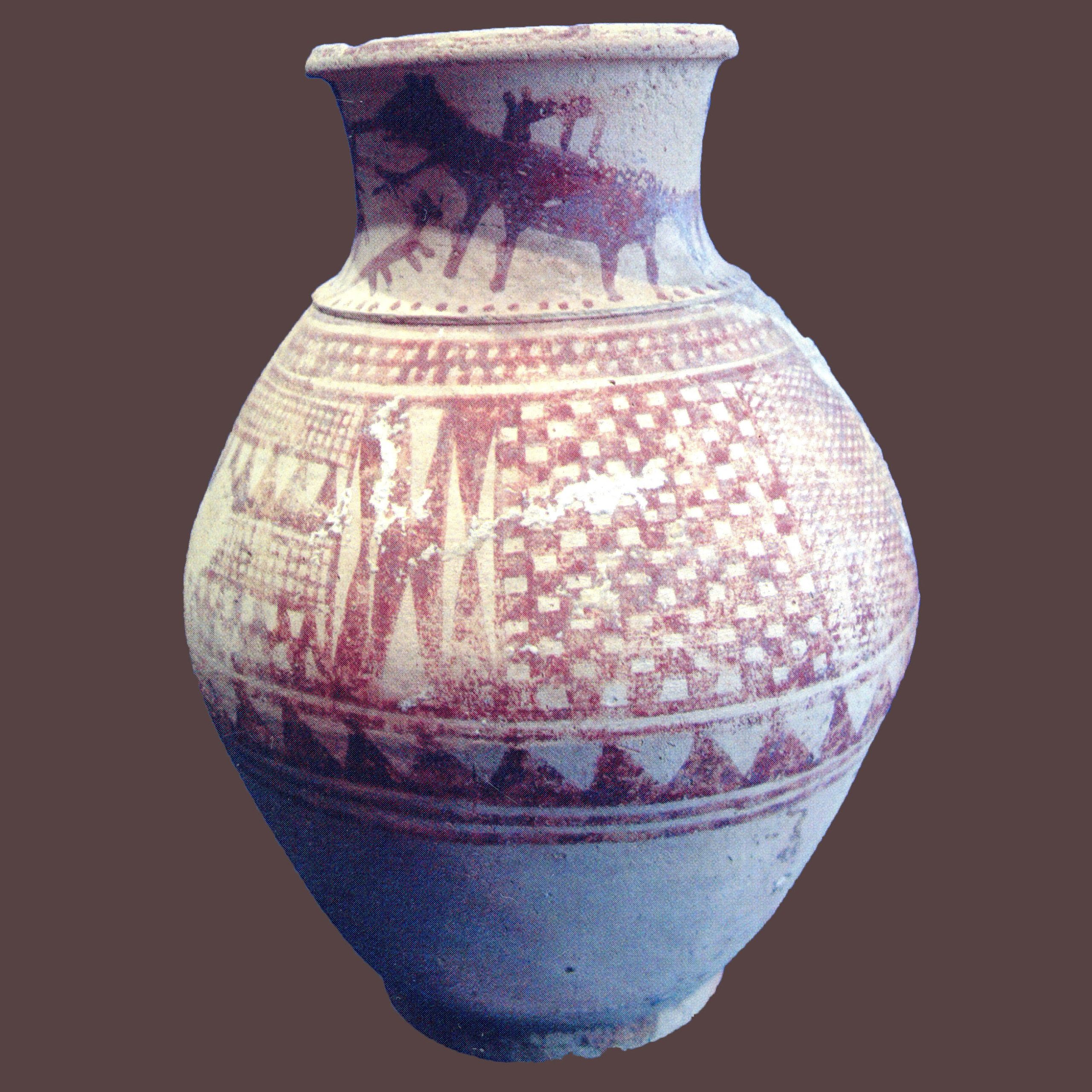

Results from the surface survey of the southeast area of Tōmb-e Bōt suggest a long sequence of settlement for the site, with the most significant phase dating to the 2nd century A.D. What has become apparent largely from the analysis of surface pottery assemblage and fragmented artworks are that the site’s heyday was during the late Arsacid/early Sasanian period, most probably at the time of the independent dynasts of Fars known as the Persis kings (Askari Chaverdi, “Post-Achaemenid Legacy of the Persian Gulf Hinterland,” pp. 144-146).

The remains at Tōmb-e Bōt recall Achaemenid art, but a closer look reveals that it lacks the most characteristic feature of the Persian court art such as high-quality materials, final finishing, and overall plastic sophistication visible on monumental artworks at Pasargadae and Persepolis, for example. Not even a single object in the assemblage reflects the fineness, meticulousness, and proportionality of Achaemenid sculpture. The typological similarities between the Tōmb-e Bōt findings and the Achaemenid remains at Persepolis are evocative of the local artist’s passionate attempt to imitate the earlier masterpieces. However, the material, dimensions and particularly the stone cutting technique are inferior. At Tōmb-e Bōt we see a decadent Achaemenid style and a general reliance on low-quality stones. Furthermore, motifs and decorative elements such as petals and buds decorating the double-protome capitals were all rendered in a local style. The revival of Achaemenid artistic styles, — albeit in a depreciated form — in the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries A.D. in southern Fars has raised multiple questions, some of which are related to the rise of the Sasanian Empire in the early 3rd century. Perhaps, the reuse and imitation of Achaemenid artistic traditions in a remote and relatively sheltered locality in the hinterland of the Persian Gulf was part of the local rulers’ efforts to consolidate national identity and to retain the territorial integrity and cultural homogeneity in the region.

Finds:

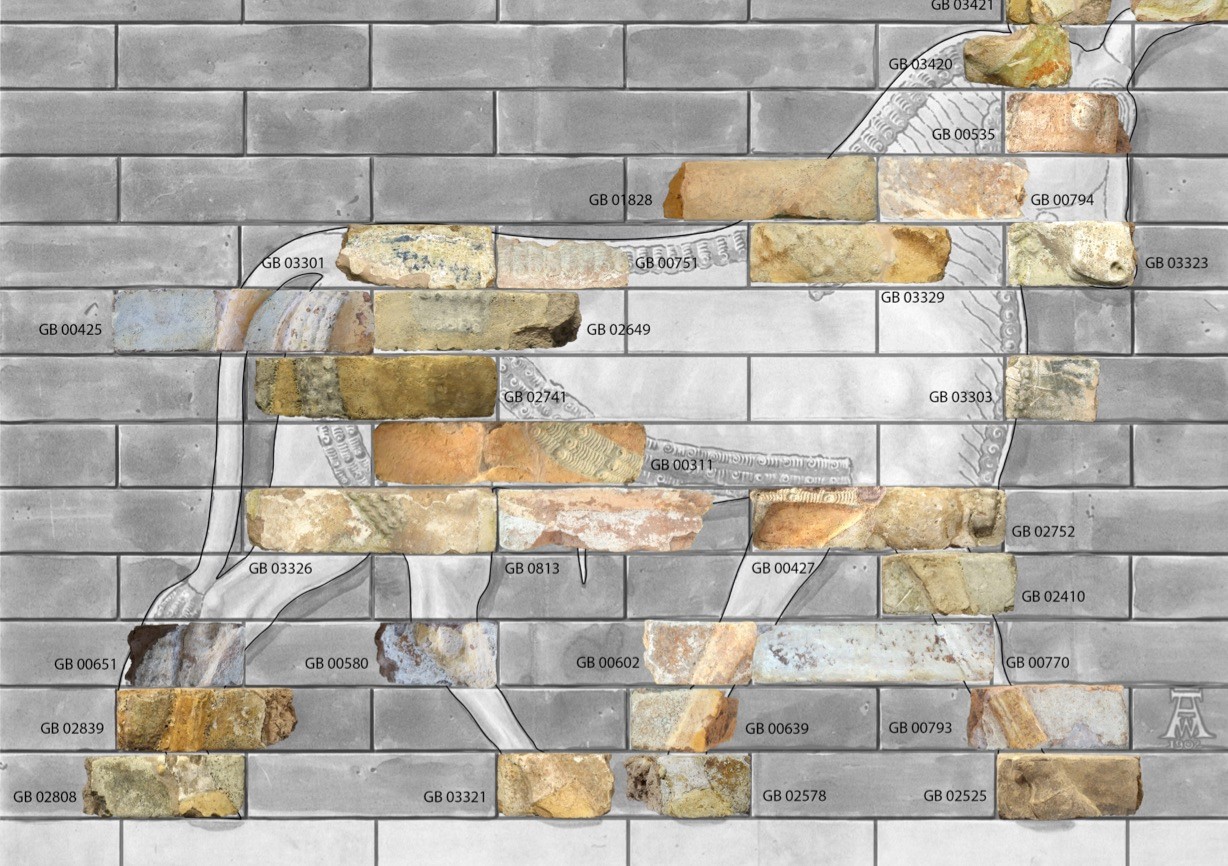

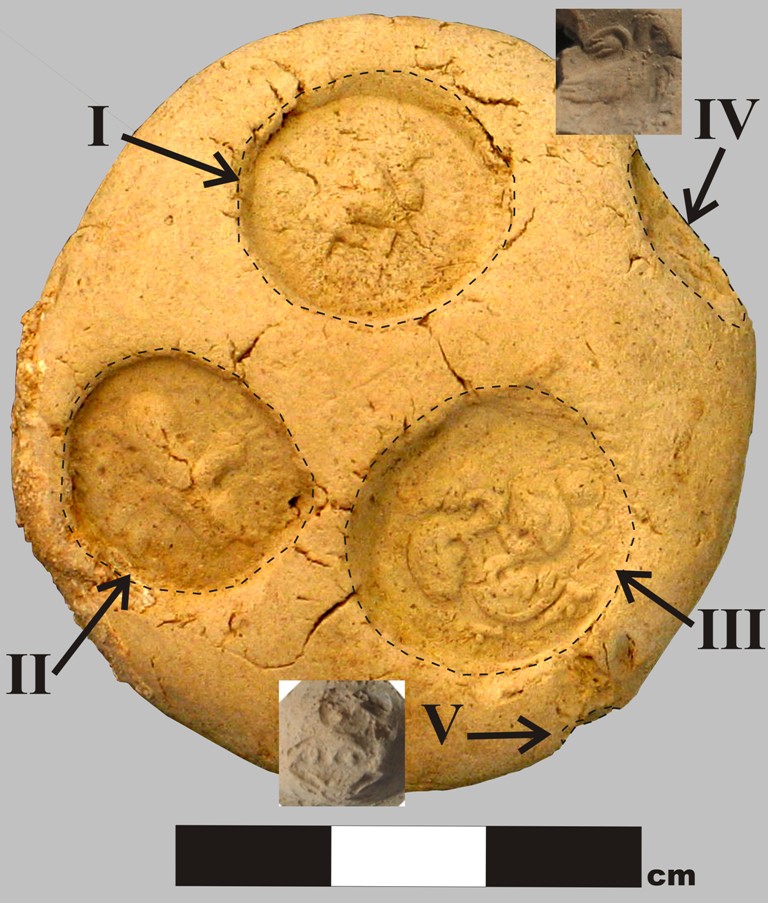

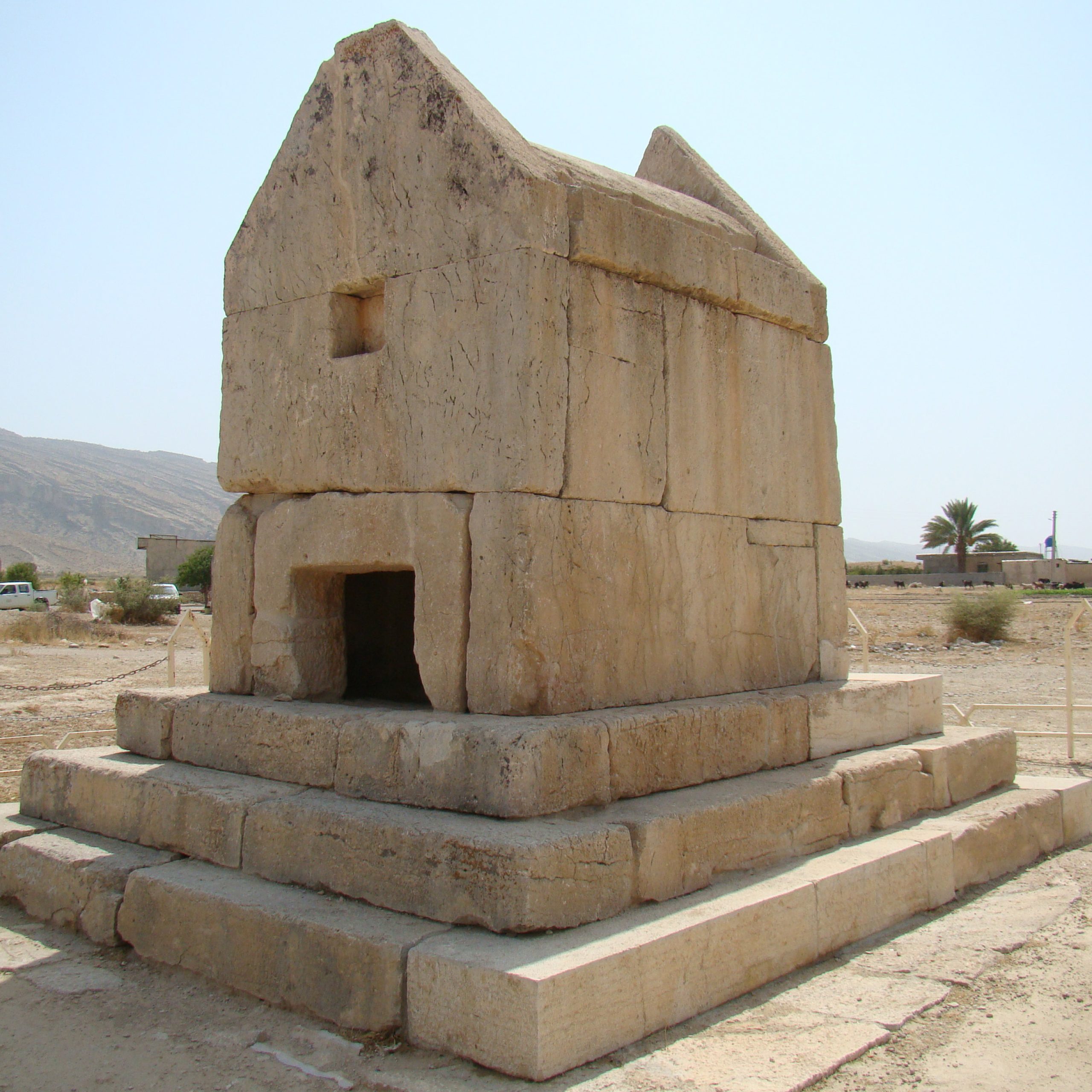

The finds consist of architectural elements, including three cubic capitals with volutes, three capitals with addorsed animal protomes, a fragmented stone human bust, and double-protomes.

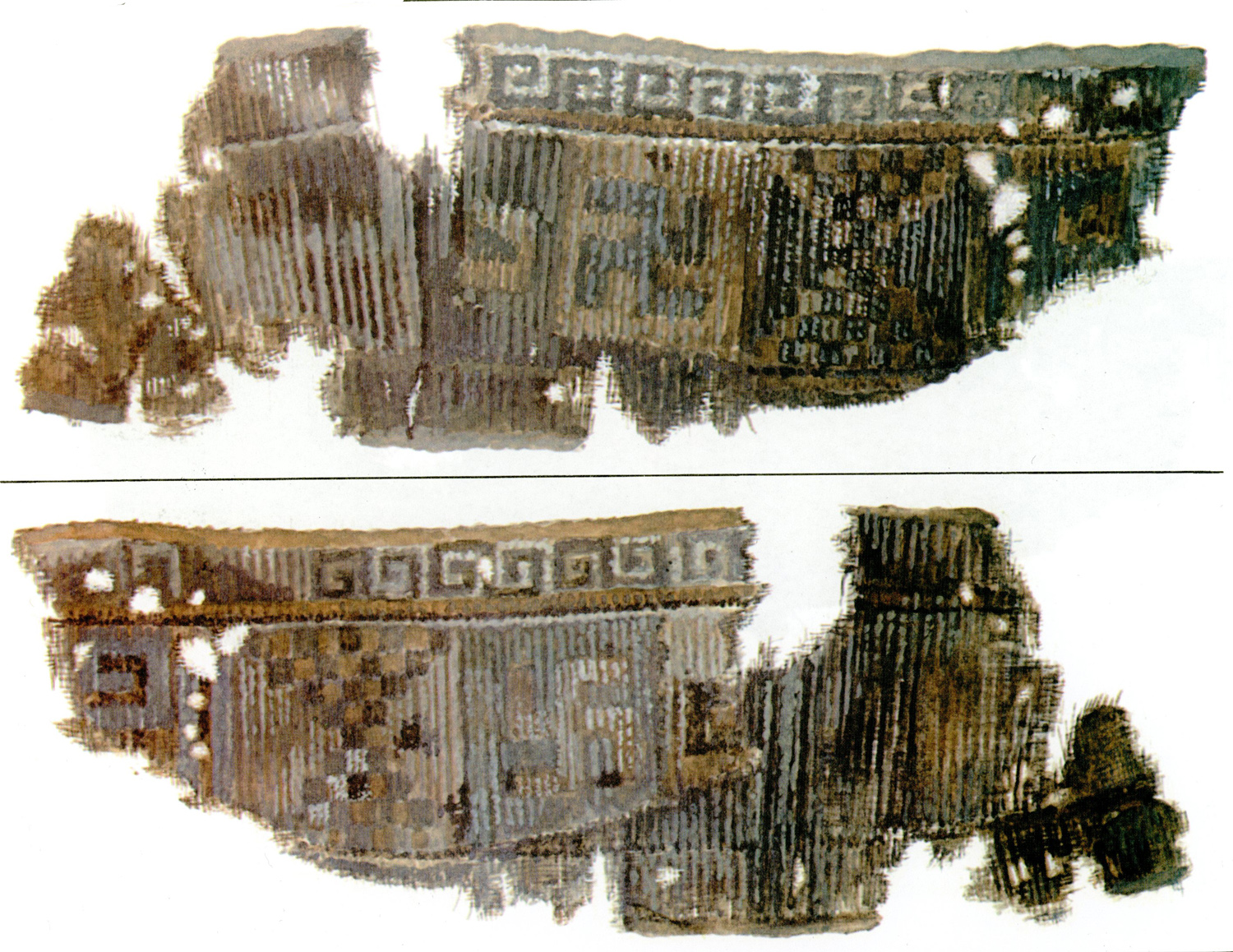

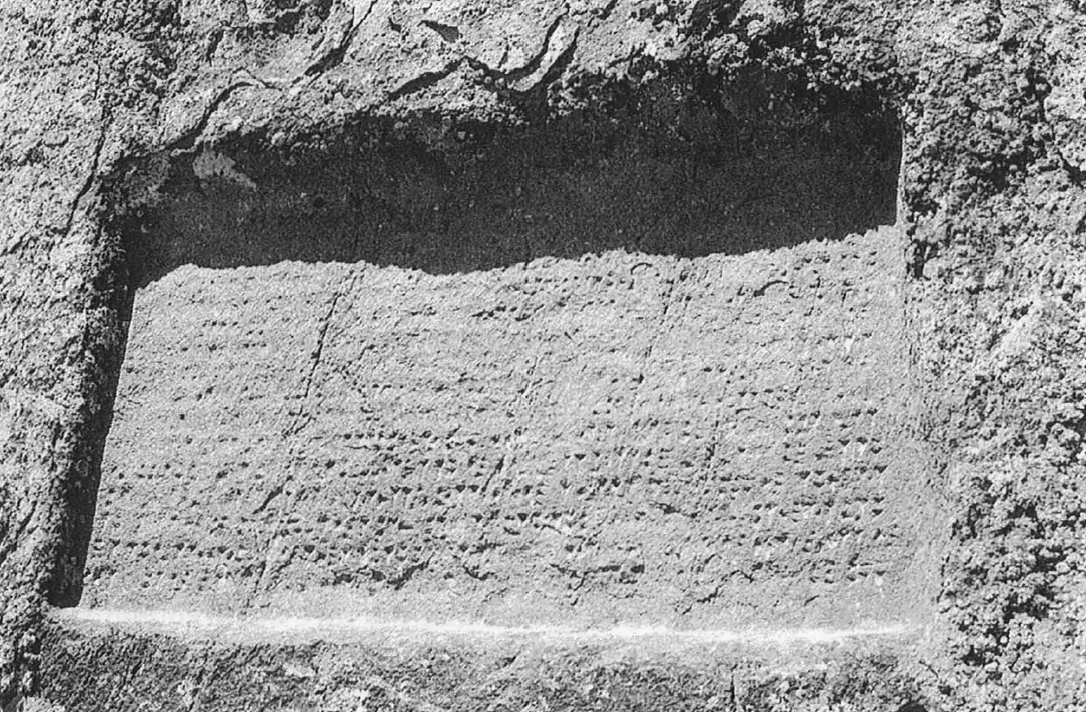

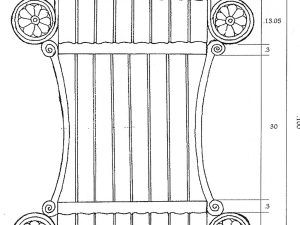

Cubic capitals with volutes: All four sides of these rectangular cuboids were embellished with multiple volutes (fig. 3, fig. 4). The better preserved of these column capitals (capital 1) is 1.10 m high and consists of three sections, lower, middle and upper (fig. 5, fig. 6).

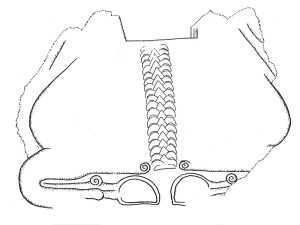

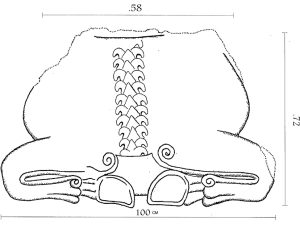

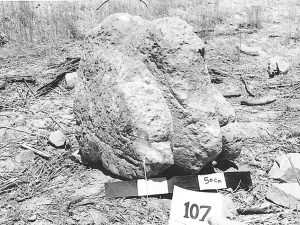

Animal protomes capitals (fig. 7, fig. 8, fig. 9, fig. 10): Two capitals are formed by a pair of addorsed kneeling animals; the heads of animals are missing, and only one side of each capital remains intact. Due to these damages, it is difficult to measure the accurate dimensions, but the extant portion of Capital 1 is 90 cm high, 107 cm long and 52 cm wide. Column 2 survives to a length of 82 cm, a width of 33 cm and a height of 72 cm. Moreover, there are two broken eagle heads in limestone with wide, long beaks and prominent head and neck which might have been parts of these animal protomes (fig. 11).

Human-Headed Bull Capital (fig. 12, fig. 13): This largely damaged sculpture represents a kneeling fantastic creature with a human head and an animal bust. The extant fragments are 66 cm high and measure 6 × 41 cm in the lower part.

Human bust (fig. 14, fig. 15): The fragment of a human bust of white limestone sculpted in full-face has survived to a height of 27 cm; it weighs 9.100 kg. Despite damages, the fat face with chubby cheeks and protruding eyes are still discernible. Though the top of the head is broken, the extant parts appear to suggest that there was originally a crown or diadem (Askari Chaverdi, “A Stone human bust from Tomb-e Bot, Fārs, Iran,” p. 69).

Fig. 3. Voluted section of a column capital (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 4. Voluted section of a column capital (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 5. Voluted section of a column capital (photo: A. Askari-Chaverdi)

Fig. 6. Drawing of the voluted section of a column capital (drawing: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 7. Bull-headed double-protome capital (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 8. Drawing of a bull-headed double-protome capital (drawing: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Bull-headed double-protome capital (photo: A. Askarai Chaverdi)

Fig. 10. Drawing of a bull-headed capital (drawing: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 11. Fragment of an eagle-headed capital (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 12. A human-headed double-protome capital (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 13. Drawing of the human-headed capital (drawing: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 14. Head of a human bust (photo: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Fig. 15. Drawing of the head of a human bust (drawing: A. Askari Chaverdi)

Bibliography:

Askari Chaverdi, A., “Fars after Darius III: New Evidence from an Archaeological Site in Lāmerd, Fars,” Bastānshenāsi va Tārikh, vol. 13, 1378/1999, pp. 66-72,

Askari Chaverdi, A., “Recent Post-Achaemenid Finds from Southern Fars, Iran,” Iran, vol. 40, 2002, pp. 277-278.

Askari Chaverdi, A., “ Post-Achaemenid Legacy of the Persian Gulf Hinterland,” Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia, vol. 23, 2017, pp 127-150.

Askari chaverdi, A., “A stone human bust from Tōmb-e Bōt, Fars, Iran,” Parthica, vol. 18, 2016, pp. 65-71.

Askari Chaverdi, A. and M. Azarnoush, “Survey of archaeological sites of the Persian Gulf hinterland: Lamerd and Mohr, Fars,” Bāstānshenāsi va Tārikh, No. 18, 2004, 1-18.

Gaube, H., “Im Hinterland von Siraf. Das Tal von Galledar/Fal und seine Nachbargebiete,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 13, 1980, pp. 149-166.

Stein, A., Archaeological Reconnaissance in North- Western India and south- Eastern Iran, New York, 1937, pp. 213-234.

Wilson, A. T., S. W. Persia: Letters and Diary of a Young Political Officer, 1907-1914, London, 1942.