Taq-e Garāطاق گرا

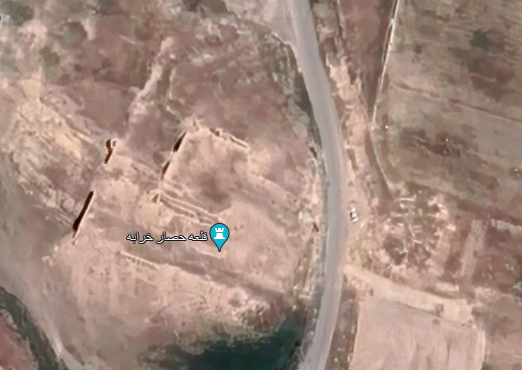

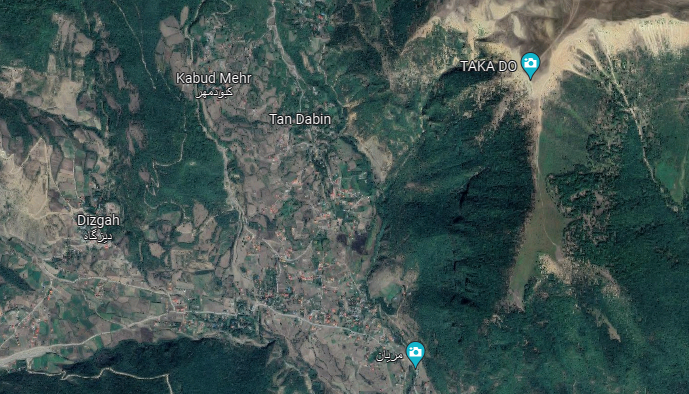

Location: Taq-e Garā is a stone monument, 17 km east of Sarpol-e Zohāb, in western Iran, Kermanshah Province.

34°25’54.6″N 46°01’02.9″E

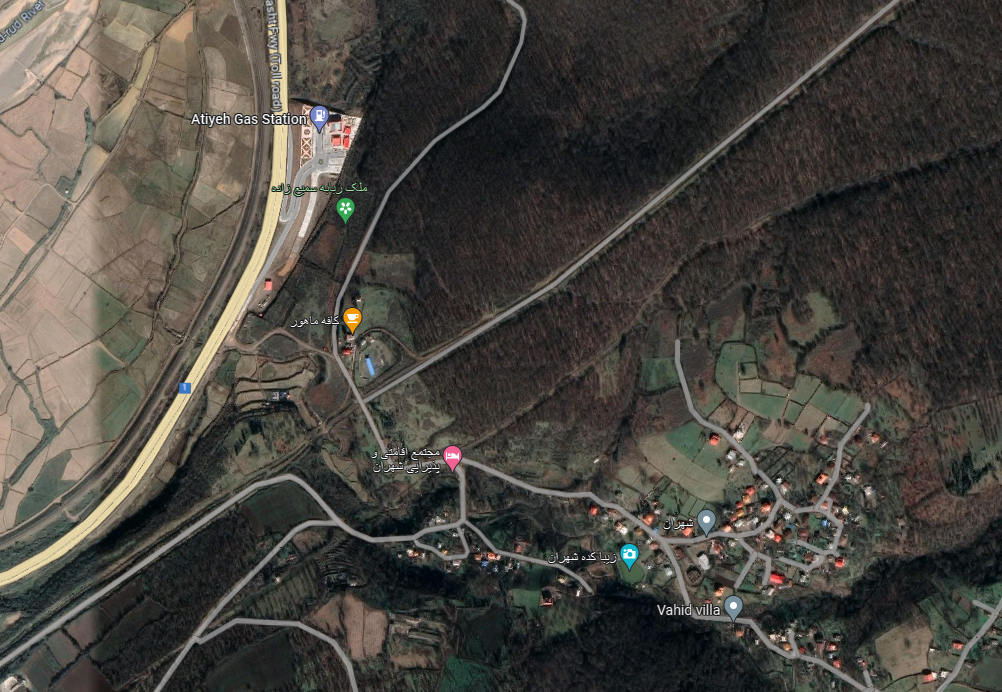

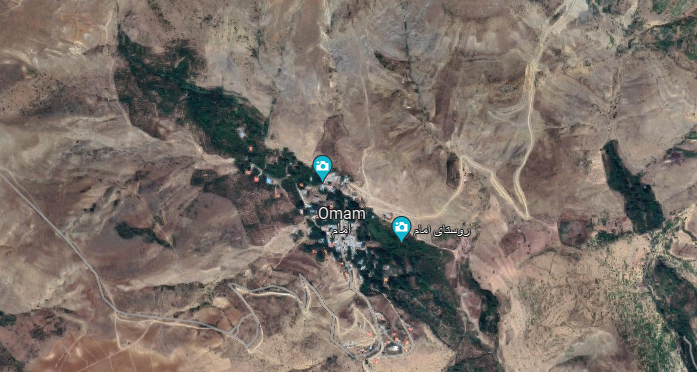

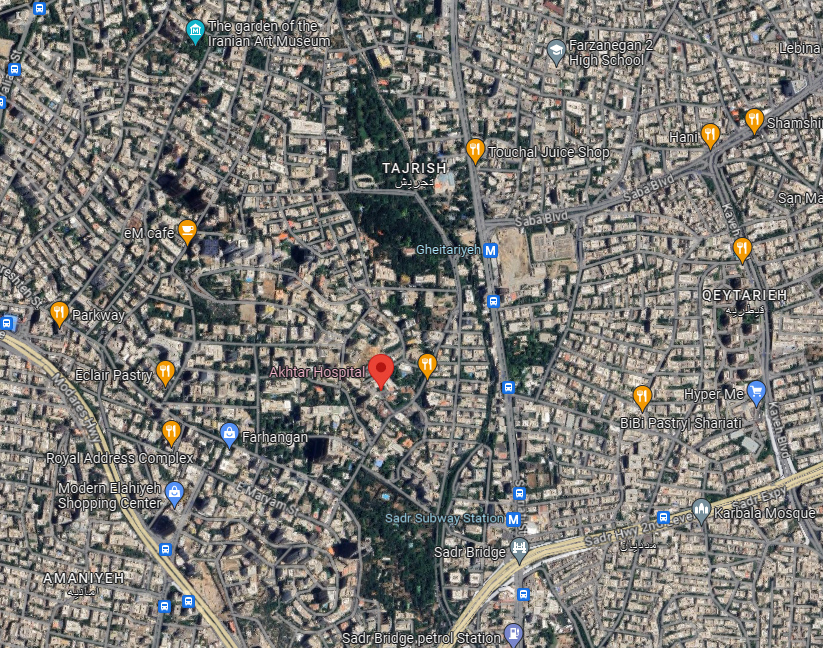

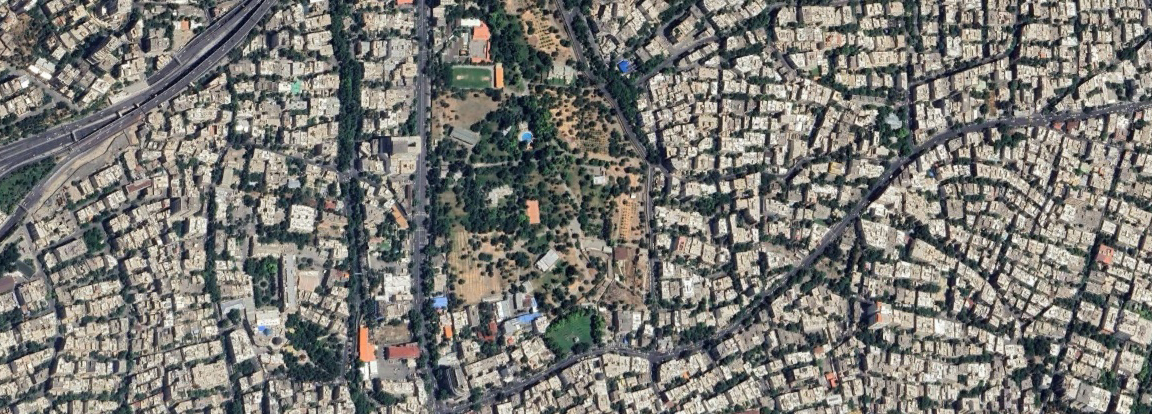

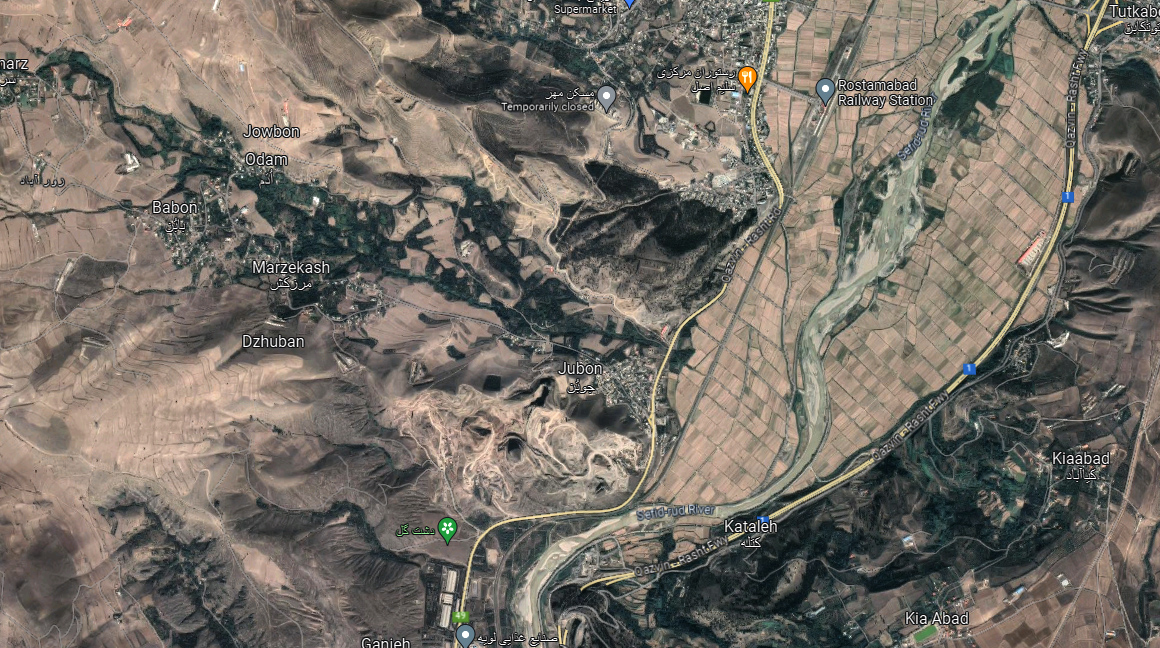

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian

History and description

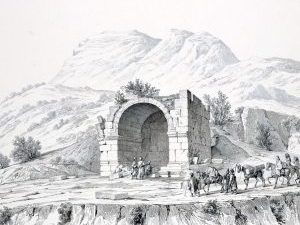

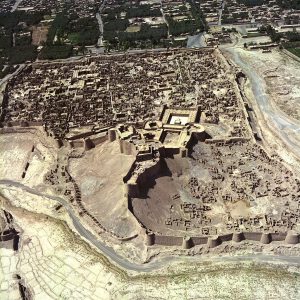

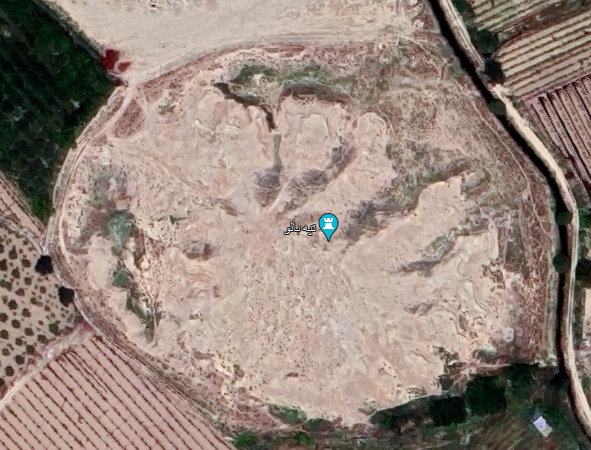

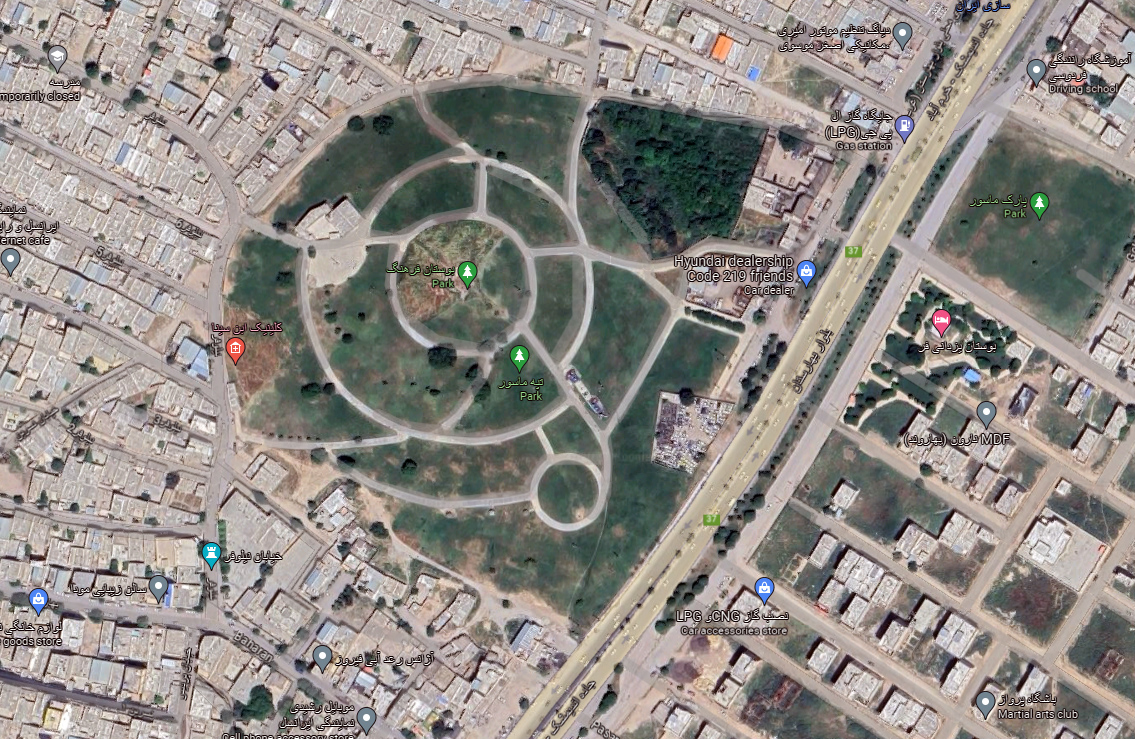

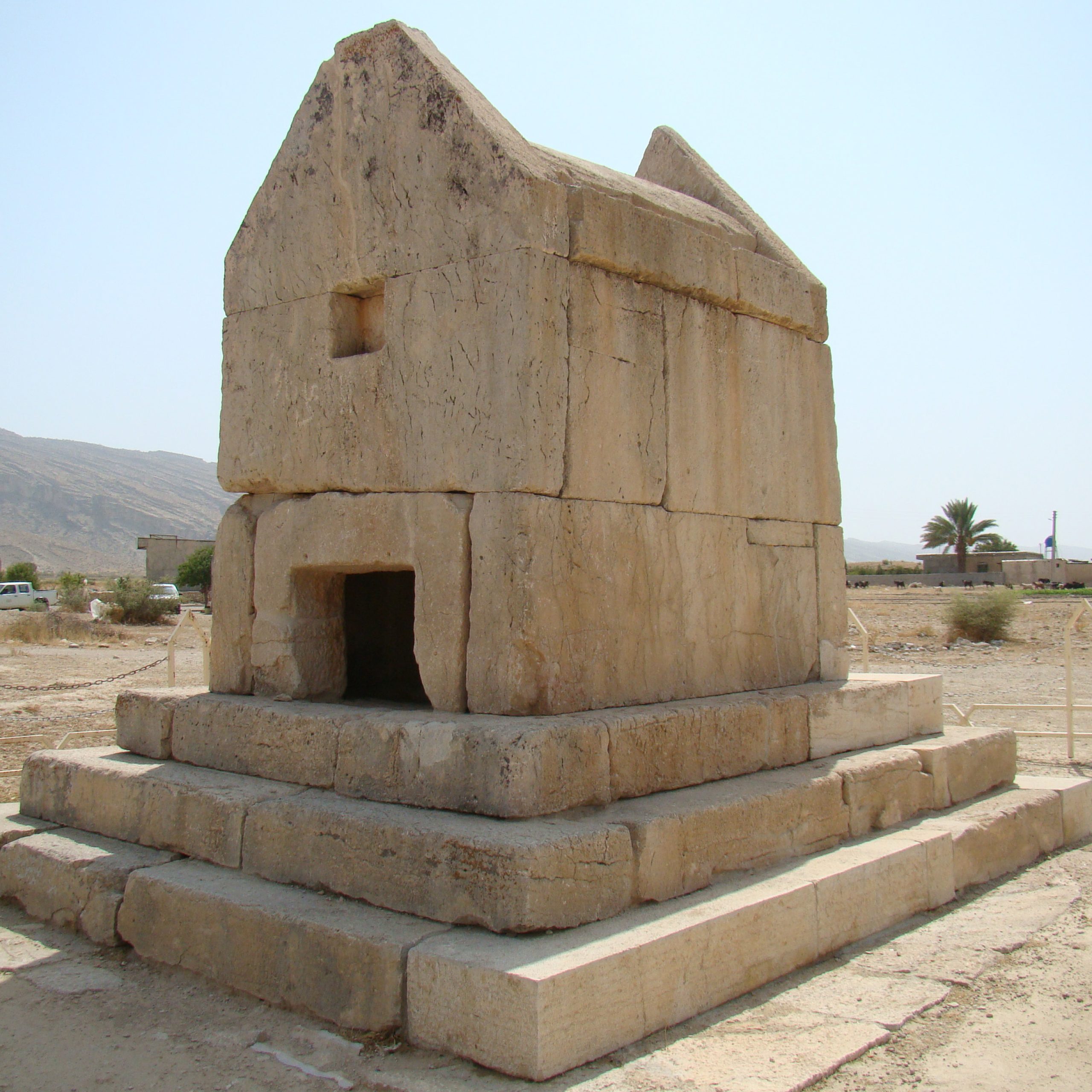

The situation of Taq-e Garā (fig. 1) is significant in that it marks the pass leading to Sarpol-e Zohāb where the are ruins of a Sasanian settlement. As Ernst Herzfeld rightly noted, it marks exactly the entrance to the Zagros Gates (fig. 2). Taq-e Garā is a parallelepiped construction in the form of an isolated eyvān. The stone monument is 11.7 m high and 7.85 m wide. The arched area forming the eyvān is approximately 5.5 m high and 4.25 m wide with a depth of 3 m. The top of the monument is decorated with crenelated pieces much the same as in other contemporary structures like Taq-e Bostān. Taq-e Garā was built on the side of the old road going to Sarpol-e Zohab and Qasr-e Shirin in the west. No inscription identifies the monument but its masonry and location suggest a construction date in the Sasanian period.

Archaeological Exploration

Taq-e Garā located on the main road connecting the Iranian Plateau to Mesopotamia has been visited by several Western explorers. Henry Rawlinson who traveled through the pass in 1836 describes it as follows:

By the geographers the pass is called 'Akabah-i-Holwán (the defile of Holwán), and among the Kurds, Gardanahi-Táki-Girráh (the pass of Táki- Girráh). The Táki-Girráh, which signifies ‘the arch holding the road' is a solitary arch of solid masonry, built of immense blocks of white marble which is met with on the ascent of the mountain; it is apparently very ancient, and the name and position suggest the idea of a toll-house for the transit duty upon merchandise crossing the Median frontier; it nearly assimilates, however, in situation to Mádaristán, which is described by the orientals [sic] as one of the palaces of Bahrám Gor; and it may possibly therefore have formed a part of it; it would also seem to denote the spot where Antiochus erected the body of the rebel Molon upon a cross.

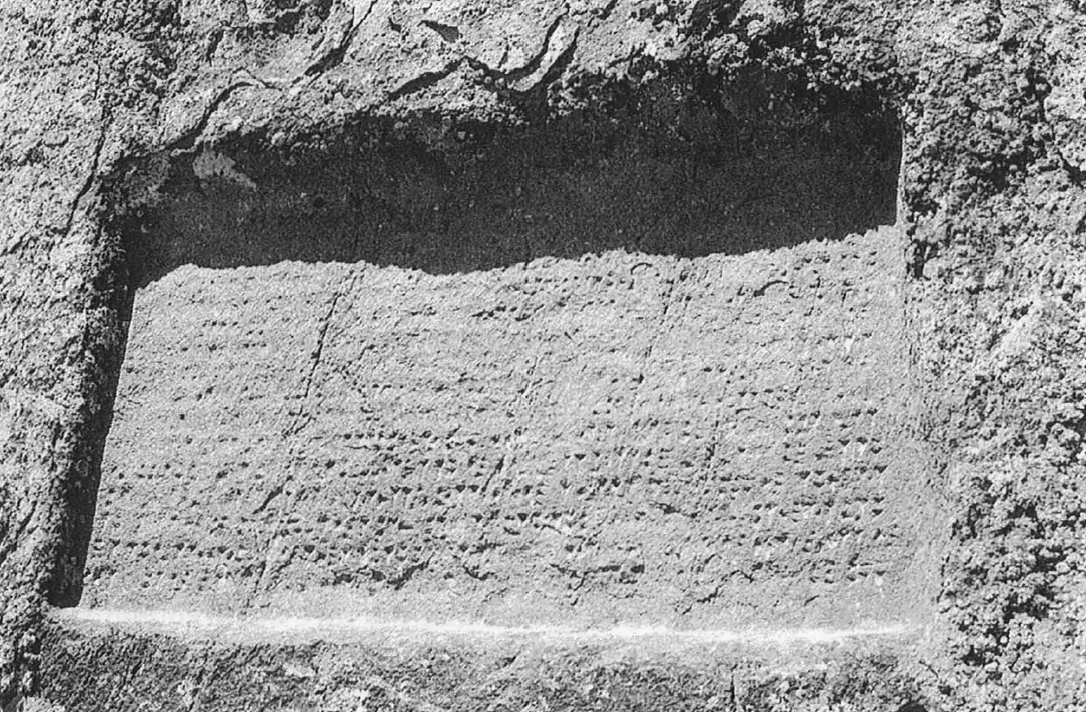

In their visual survey of Iranian monuments in the 1840s, Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste described the Taq-e Garā and published its first views, including accurate measurements of the monument (fig. 3).

Jacques de Morgan, mistakenly naming the monument Takht-i Ghirra, describes it and conjectures that the statue of the king who constructed the monument might have been positioned beneath the vaulted area (inside the eyvān). He wrote that the monument was in very poor condition; its cornice had fallen. He added that in the debris lying on the ground, one could still find the elements for its reconstruction. He admired the monument’s masonry as being finely crafted. De Morgan took the first photograph of Taq-e Garā showing its deplorable state of conservation in the 1890s (fig. 4).

The thorough study of the monument is by Ernst Herzfeld who visited it in 1905. He described the location of the ruined building first in his Reisebericht and rightly realized that Taq-e Garā marked exactly the entrance to the Zagros Gates, as referred to in Classical sources. Herzfeld also wrote on the meaning of the name Taq-e Garā, thus conforming to Rawlinson’s expression of the “arch holding the road.” His photographs of the Taq were published in the seminal book on Iranian rock-reliefs, Iranische Felsereliefs, co-authored by Friedrich Sarre and published in 1910.

In December of 1970, Tāq-e Garā was visited and surveyed by Wolfram Kleiss and Hubertus von Gall on behalf of the German Archaeological Institute. Kleiss is the first archaeologist to observe and record the adjacent remains on the south side of the old road; the remains are likely traces of a stone quarry and excavations for the construction of the monument (see Von Gall, pp. 222-225).

The serious fieldwork on Taq-e Garā was launched in 1971 as part of a restoration project led by Seyfollah Kambakhsh Fard on behalf of the National Office for the Restoration and Protection of Historical Monuments of Iran. Kambaksh Fard’s excavations in the vicinity of the ruined building yielded numerous fallen fragments, including crenelated pieces that once adorned the monument’s top.

Bibliography

De Morgan, J., Mission scientifique en Perse, vol. 4, part 2, Paris, pp. 337-339, figs. 204-205, pl. 39.

Flandin, E. and P. Coste, Voyage en Perse, text, pp. 172-173; plates, vol. 4, pp. 214-215.

Herzfeld, E., “Eine Reise durch Luristān, Arabistān, und Fārs,” Petermanns Mitteilungen, vol. 53, 1907, p. 54.

Kambakhsh Fard, S., Ma’bad-e Anahita, Kangāvar, Tehran, 1374 H/1996, pp. 341-370.

Sarre, F. and E. Herzfeld, Iranische Felsereliefs, Berlin, 1910, pp. 232-235.

Rawlinson, H. C., “Notes on a March from Zoháb,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 9, 1839, p. 34.

Von Gall, H., “Entwicklung des Thrones in Iran,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 4, 1971, pp. 222-225, figs. 4-6.