Takht-e Sōleymān/Atūr Gūshnasp/Shiz/Ganzak/Saturiq/Suqurluqتخت سلیمان/آذزگشنسب/ شیز/گنزک//ستوریق/سوقورلوق

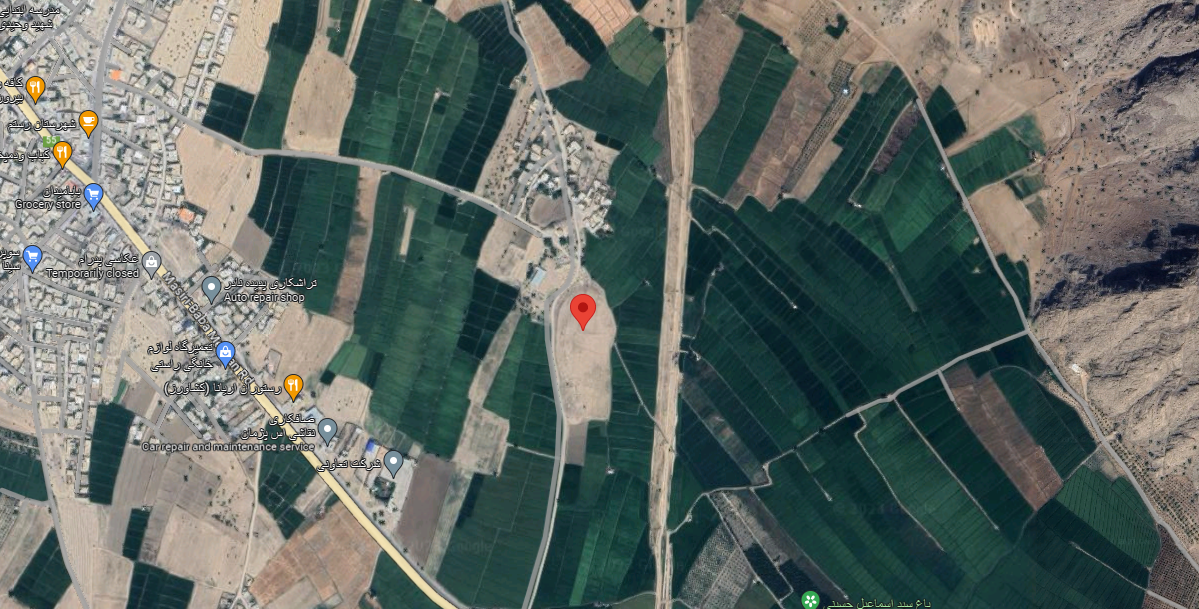

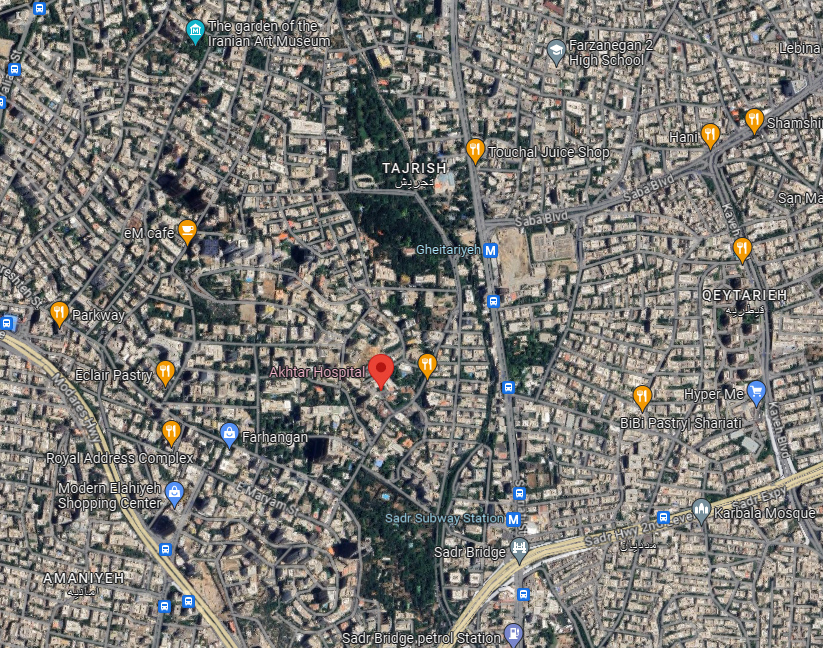

Location: The Sasanian fire temple at Takht-e Sōleymān is located in the mountains of northwestern Iran, West Azarbaijan Province

36°36’14.99″N 47°14’5.70″E

Location:

Historical Period:

Achaemenid, Parthian, Sasanian, Islamic/Mongol/Ilkhānid

History and Description:

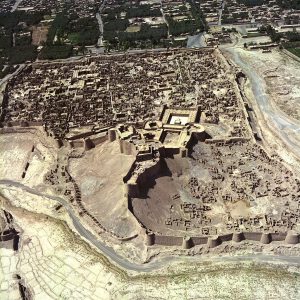

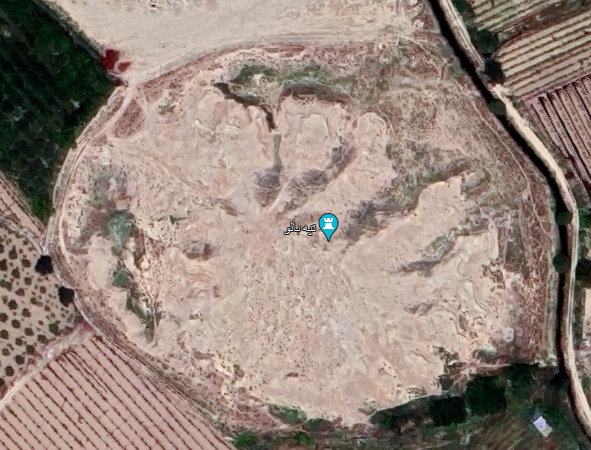

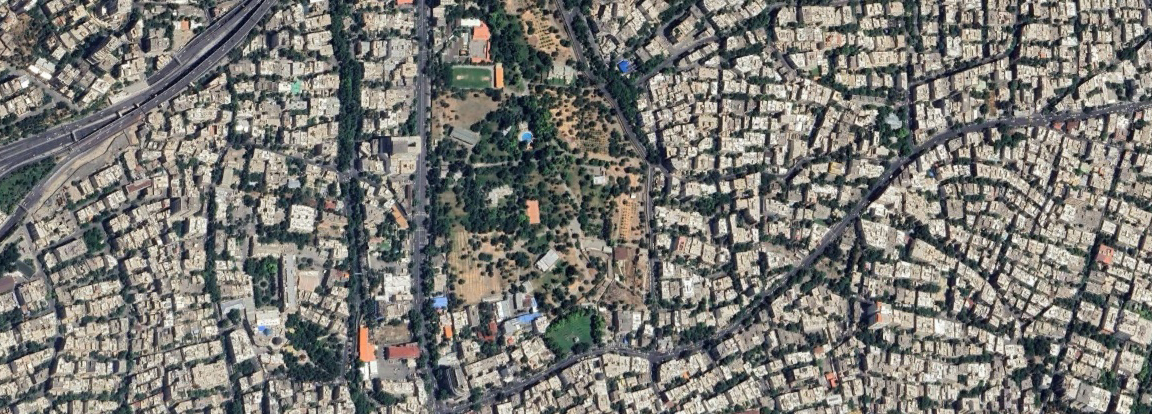

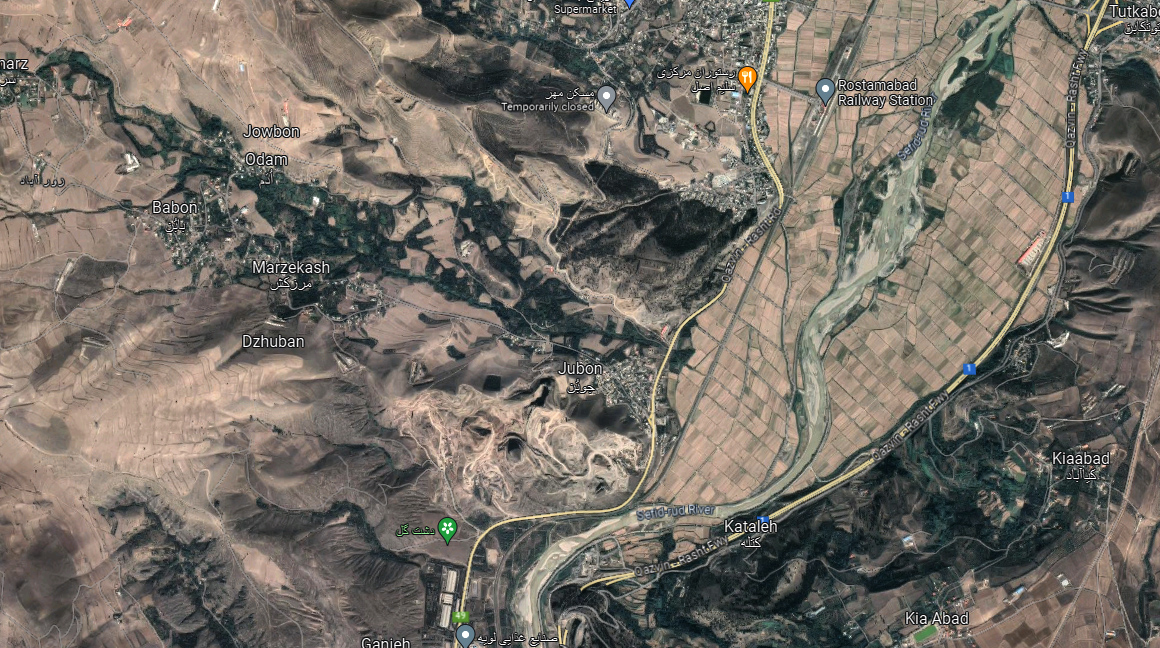

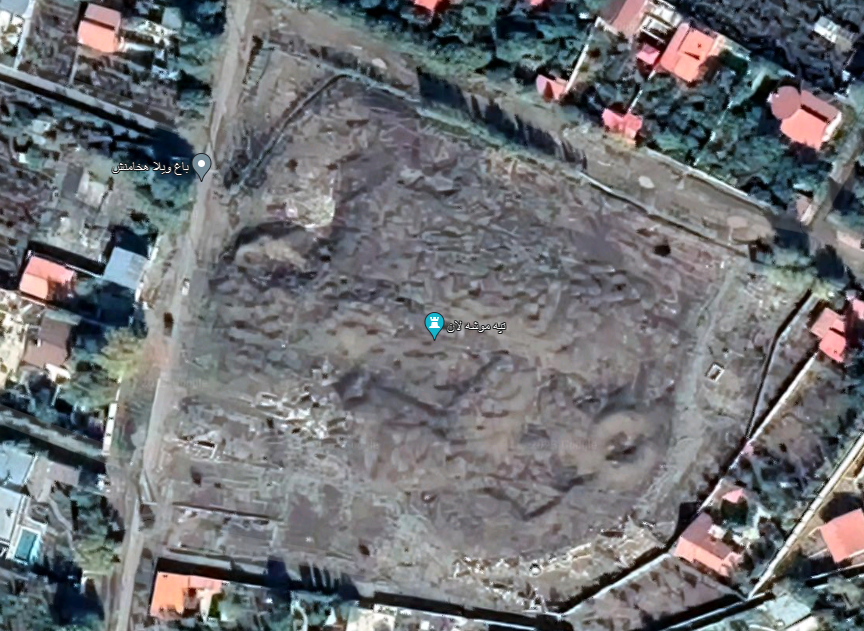

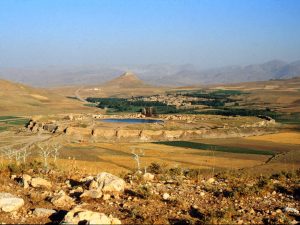

Located some 40 km north/northeast of the town of Takāb, at an altitude of 2500 m above sea level, Takht-e Sōleymān is surrounded by high mountains exceeding 3000 m in elevation. The World Heritage site of Takht-e Sōleymān lies on an outcrop of limestone, 60 m above the surrounding plain, which is built up as a result of the overflowing of calcareous water from an artesian source (fig. 1). In the course of millennia, the source has formed a deep thermal lake of 80 m in diameter from which water has continuously flowed. The 20° Celsius water is sulfurous and undrinkable but it contains lime, which is essential for agriculture. The water has made a number of stone channels and irrigates cultivated fields in the surrounding plain, one of which has taken the name of azhdehā (dragon) because of its sinuous shape and is believed to be petrified by Prophet Solomon. In spite of legends associated with the ruins around the lake, archaeological finds have revealed that Takht-e Sōleymān is the site of the royal fire temple of the Sasanian Empire known as Atūr-Gūshnasp (the Fire of Stallion) /the Fire of Knights attested on excavated inscribed seal impressions found at the site. Other toponyms have been associated with the site: Phrāatā/Phrāaspā, Verā, Ganzaka/Gazaka, Thebarmais, Ğanza/Ğaznak, and Šiz/Shiz (for a survey of the primary sources and toponyms, see Jackson, Persia. Past and Present, pp. 132-142; Minorsky, “Roman and Byzantine Campaigns in Atropatene,” pp. 254-263; Tardieu, “Les gisements miniers de l'Azerbayjān méridional,” pp. 257-258; an impressive list of the primary sources for Takht-e Sōleymān is given in Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, pp. 309-325, and pp. 339-357, for a discussion on the toponyms). Sebeos, an Armenian bishop and historian of the seventh century, associated the site with Všnasp/Gūshnasp/Atūr-Gūshnasp. While the place name Šiz/Shiz, known from Islamic and medieval sources, is confirmed to be the site of Takht-e Sōleymān, the toponym Ganza or Ganzak of Byzantine, Armenian, and Syriac sources refers to another site possibly in the region of Marāgheh (Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, p. 350; Boyce, “Ganzak,” Encyclopedia Iranica). Medieval, Islamic sources such as Tabari, Yāqut, Mas’udi, and Qazvini refer to the site as Shiz, and Abū-Dūlaf Mis’ar ibn Muhalhel, writing in the tenth century, gives the best medieval account of the ruins in which he describes the fire temple (see Minorsky, Abu Dulaf Mis’ar ibn Muhalhil’s Travels in Iran, pp. 31-32):

The walls of this town [Shīz] encircles the lake which is bottomless. I sounded it to a depth of 14,000 cubits odd and the plumb did not come to rest. Its area is about one jarib hāshimi and when its waters have moistened the earth the latter immediately solidifies to stone. Seven canals come out of the lake and each of them feeds a mill and comes out under the walls. In Shīz there is a greatly respected fire-temple from which the fires of the Magians are kindled both in the East and in the West. On the summit of its cupola, there is a silver crescent which forms its talisman. Both amirs and usurpers wished to remove it but did not succeed. And another wonder of this temple is that the hearth has been burning for 700 years and no ashes are found in it, whereas the fire has not ceased to burn for an hour. This town was built by Hurmuz b. Khusrān-Shīr b. Bahrām of stones and lime. By this temple, there are tall porticoes and awe-inspiring buildings.

In the thirteenth century, Hamdollah Mostowfi recorded the site’s name as Satūriq as he wrote (The Geographical Part of Nuzhat-al-Qolūb, p. 69):

In the Anjarud district is a city which the Mongols call Saturiq: it stands on the summit of a hill and it was originally founded by King Kay Khusraw the Kayānian. In this town there is a great palace, in the court of which a spring gushes forth into a large tank, that is like a small lake for size, and no boatman has been able to plumb its depth. Two streams of water, each in power sufficient to turn a mill, continually flow away from this tank: but if they be dammed back the water in the tank no wise increases in level; and when the stoppage is removed the water again runs away as before: being at no season more or less in volume. This is a wonderful fact. This palace was restored by Abaqā Khān the Mongol, and in the neighbourhood there are excellent pasture grounds.

Satūriq is probably a corruption of Sūqūrlūq, a Turko-Mongol name, the etymology of which is still unclear. Scholars of Turko-Mongol studies such as Louis Bazin and John Andrew Boyle, exploring the etymology of the word in length, have not been able to reach a conclusive answer. Both Bazin and Boyle write that the name is originally Turkish, meaning “place of marmots” (Bazin, “Note sur le turc suġur (soġur?) “marmotte”; Boyle, “Sites and localities connected with the history of the Mongol Empire,” p. 79, note. 31). Tomoko Masuya gives a long discussion on the etymology of Sūqūrlūq, taking account of all the pertaining Western interpretations as well as Chinese sources (Masuya, The Ilkhanid Phase of Takht-i Sulaiman, pt. 1, pp. 77-86). However, there is yet another possibility. If we read the word as sū-qūrlūq instead of sūqūrlūq, then the meaning changes. Sūqūrlūq consists of “سو” (water) and “قورلوق” (build). This could then become “water build” or the “building by the water”, which could be referring to structures beside the lake. Alternatively, taking “قورلوق” as the “place for fire” (like Perso-Turkish qorkhānā), it would then become “the fire adjacent to the water”. The latter makes more sense (for a discussion, Jafari, “Takht-e Sōleymān yā Sūqūrlūq,” p. 34, whose proposed etymology does not seem to be convincing either). The name Sūqūrlūq is first seen in a contemporary source, Jām’e al-Tavārikh by Rashid al-Din, written in the 13th century. Sūqūrlūq was still in use in the Timurid period as Hafez Abrū refers to it in his Zobadat al-Tavārikh written in 810/1407. Therefore, the ruins took the name Takht-e Suleiman (Throne of Solomon) likely after the complete abandonment of the site. Despite the fact that a number of scholars such as Vladimir Minorsky and Muhammad Qazvini believe this name to be a later invention of popular imagination (Safavid or later), the attribution of ancient ruins to Solomon had a much longer presence in Iranian history as evidenced by Achaemenid ruins in Fars (Sarfaraz, Takht-e Sōleymān, p. 14; Mousavi, Rāhnamā-ye Takht-e Sōleymān). The oldest text referring to the site as Takht-e Sōleymān is the sixteenth-century history book, Lōbb al-Tavārikh, in which the author, Amir Yahyā Qazvini, mentions the place where Shah Ismail spent some time camping and hunting in the summer of 910/1504. The name appears also in Mirza Mōhammad Tāher Vahid Qazvini’s sixteenth-century book, Tārikh-e Jahān Ārā-ye Abbāsi. (Jafari, “Takht-e Soleymān ya Sūqūrlūq,” pp. 84-85). Indeed, the name Takht-e Sōleymān (Throne of Solomon) with other adjacent structures attributed to Solomon such as Zendan-e Sōleymān (Solomon’s Prison), Taviley-e Sōleymān (Solomon’s Stables), and Takht-e Belqeys (Belqey’s or Queen of Sheba’s Throne) appeared sometime between 1407 (the date of the last mention of Soqūrlūq) and 1504; the latter date is the earliest reference to Takht-e Sōleymān associated with the ruins (Huff, “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica). Regarding the name, Robert Ker Porter recounts a curious story at the time of his visit to the ruins (Ker Porter, Travels, vol. 2, p. 561):

The hill and the lake, and the ruins before us, our guide ascribed to King Solomon the Wise, the great comptroller of all the natural, and half the spiritual world ! But on my telling my Sian Kala mehmandar, that Solomon of Judea had nothing to do with building towns in Persia, he then said, “the founder of this city must have been Shah Sulieman, the fifteenth caliph. And the reason he gave was, that he had himself seen a grant of some villages in the neighbourhood, to which that sovereign's seals were prefixed ; one bearing his name, and the other something like a sun and moon. How far this may be true, I cannot vouch.

Takht-e Sōleymān before the Sasanians: The earliest occupation at the site, discovered in the 1968 campaign, was a humble agglomeration of houses in mud-brick with intramural graves in an area that became later the West Fire Temple complex (Naumann, Huff, Schnyder, “Takht-i Suleiman: Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1965-1973,”, pp. 138-140; Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, pp. 30-34, fig. 12-13; Huff, “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica). The settlement had rectangular houses in mud-brick with foundations and lower courses built of irregular pieces of rock in herringbone patterns. The mud-brick structures and tombs have been dated to the fifth century B.C. based on finds such as beads, pottery, and bronze objects (Rudolf and Elisabeth Naumann, Takht-i Suleiman, p. 24). Traces of canals show that the inhabitants of the Achaemenid period hamlet at Takht-e Sōleymān made use of the lake’s water for agriculture purposes. Several graves, containing twenty-six skeletal remains of this period, were found in the excavated sector (Kniebel, Paläodontologische Untersuchung der Skelettfunde vom Takht-i Suleiman, pp. 17-23). The settlement was abandoned after a few generations. Dog skeletons were found in the graves, with two individually buried dog skeletons (Naumann, Huff, Schnyder, “Takht-i Suleiman: Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1965-1973,” p. 140).

The layer superposing the Achaemenid settlement yielded Parthian potsherds known as Clinky or Cinnamon Ware. The stratum in which such ceramics were found was beaten and leveled down several times. No significant structure appeared in the excavation of this area (Naumann, Huff, Schnyder, “Takht-i Suleiman: Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1965-1973,” p. 140). Scant remains of a poorly preserved fortification discovered along the northern edge of the lake have been dated to the Parthian period. It consists of the foundation of a semi-circular bastion and its flanked walls excavated under the great Sasanian eyvān (Huff, “Takht-i Suleiman,” p. 293). Given the scant remains of a Parthian occupation, the identification of Takht-e Sōleymān with Parthian Phrāaspa that Anthony besieged in 36 B.C. can no longer be held in the light of Minorsky’s study of the toponyms and geographical history of the region and German excavations at the site (see discussions in Minorsky, “Roman and Byzantine campaigns in Atropatene, pp. 258-263, who places it in the vicinity of Marāgheh; Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuereheiligtümer, pp. 339-341). The fortified complex with its palace, fire temple, and adjacent buildings hardly left any space for such densely populated towns (Phrāaspā or Ganzak) as had been suggested by early travelers and visitors to Takht-e Sōleymān. As early as 1905, Alexander Friedrich von Stahl, the German geologist serving as the Post-Master General of the Persian Telegraph Company from 1893 to 1933, rightly wrote that the site could not be the place of a large city because of its geographical situation (Stahl, “Reisen in Zentral und Westpersien,” p. 32):

Nichts deutet darauf hin, daß hier einst eine größere Stadt stand, denn außer den Ruinen innerhalb der fast runden ca 1500m im Umfang messenden Festimgsmauer, in deren Mitte sich der runde See befindet, ist in der ganzen Umgebung keine Spur von Ruinen vorhanden, und der alte, versinterte Aquädukt, der im S von Tacht-i-Suleiman das kleine Tal kreuzt, hatte jedenfalls den Zweck gehabt, früher dagewesene Gartenanlagen zu bewässern. Auch die Lage mitten im Gebirge, abseits von allen größeren Verbindungswegen, ist durchaus für eine größere Stadtanlage ungünstig, wie auch das Klima hier im Winter recht rauh sein muß.

Ruins of the Atūr Gūshnasp fire temple: The extra-regional importance of Takht-e Sōleymān began with the construction of a spacious, regular mud-brick complex on the north side of the lake, probably in the fifth century. In the fifth century, a mud-brick wall on a stone foundation, 12 m thick, with semi-circular towers enclosed the structures belonging to an early sanctuary or fire temple that was built in the northern sector of the site. Silver coins of Theodosius II (402 - 450 AD) and Peroz (457 - 484 AD) suggest a fifth-century date for that early establishment at the site. The mud-brick complex underwent multiple alterations and extensions; in some areas, it was used in the masonry of the later stone structures. Given the uninterrupted transition from mud-brick structures to stone masonry, preserving the same layout and floors, it is quite possible that the mud-brick construction was an early fire temple (Huff, “Takht-i Suleiman,” p. 293). The discovery of copper coins from the reign of Kavād I (r. 499-531) above the ruins of the mud-brick walls reveals that the monumental transformation of the site must have taken place in the latter part of Kavad’s reign and must have been carried out under his son, Khosrow I Anūshiravān (r. 531-579). According to German excavators of the site, Rudolf Naumann and Dietrich Huff, the event that might have impacted the architectural transformation at the site was the suppression of the Mazdakid revolt in 528. Apparently, during the revolt, mud-brick buildings were either not repaired or had suffered from riots and civil conflicts. Later, Khosrow I moved the sacred fire from Shiz to the site of Takht-e Sōleymān.

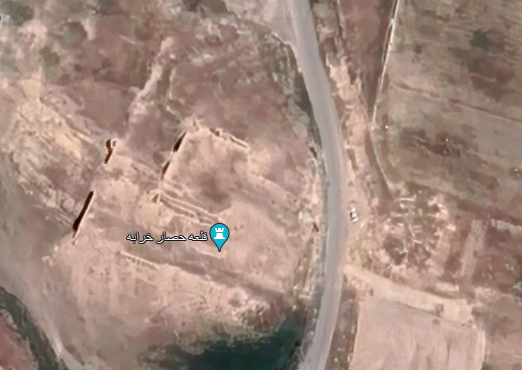

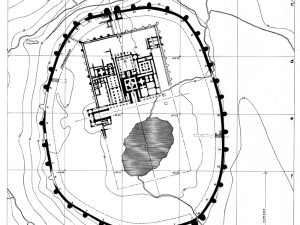

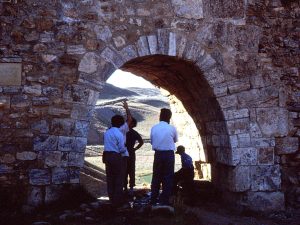

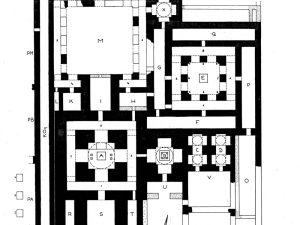

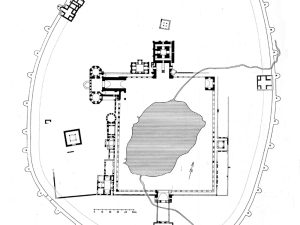

The new constructions lasted for about 100 years and were all built to the north of the lake (fig. 2). A strong wall of rubble masonry and ashlar blocks reinforced with 38 semi-circular towers protected the whole compound (fig. 3). The area within this oval sacred city had two main gates, one in the north and the other in the southeast. The excavation of the northern gate showed that it replaced an older gate in mud-brick and recent investigations at the foot of the gate yielded a collection of inscribed seal impressions, the study of which has not been yet published. During the 1970 excavation campaign, substantial restoration work was carried out at the southeastern gate of the perimeter wall (figs. 4, 5, 6) and at the fire temple complex under the direction of Mahmoud Mousavi on behalf of the Iranian Office of the Restoration and Conservation of Historical Monuments (Huff, "Survey of Excavations 1969-70," p. 181). Both gates seem to be 3 m wide and 6.30 m high, flanked by massive, crenelated semi-circular towers 11 m high.

Inside the fortified oval, there are three separate built areas: a large square, 160 x 160 m, enclosing two fire temple complexes; a second square approximately the same size as the first one, encircling the lake; a large building, probably a palace with eyvān at the juncture of the two squares; and buildings of the Ilkhanid period along the western edge of the lake.

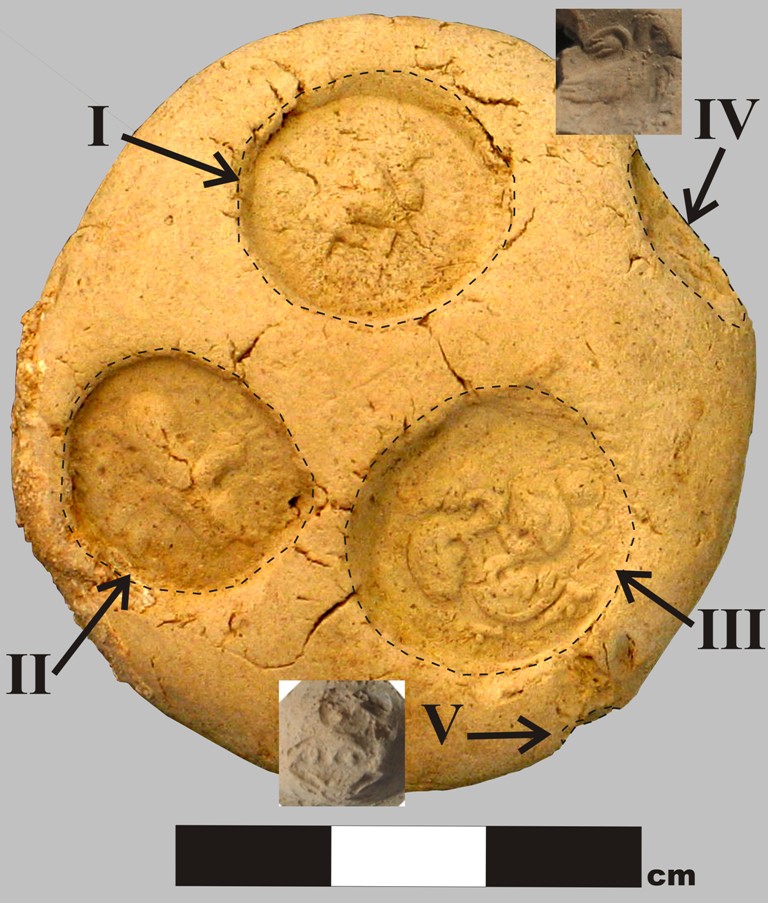

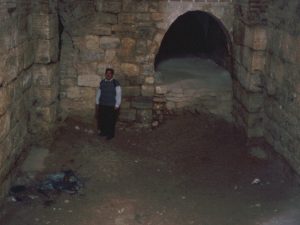

The Sasanian palace built on the northwestern corner of the lake consists of a large eyvān 8 m wide, 20 m deep, and 12 m high (figs. 7, 8). The entrance to the palace was through an antechamber from the south (figs. 9 and 10). The Sasanian eyvān was later modified and redecorated in the Ilkhanid period. The eyvān's southern pier collapsed sometime after the 1940s. For the conservation of the only surviving northern pier, scaffolding was set up in 1971-72. Traces of the base of a vaulted hall on the opposite side of the lake suggest the existence of an eastern eyvān in the Sasanian period.

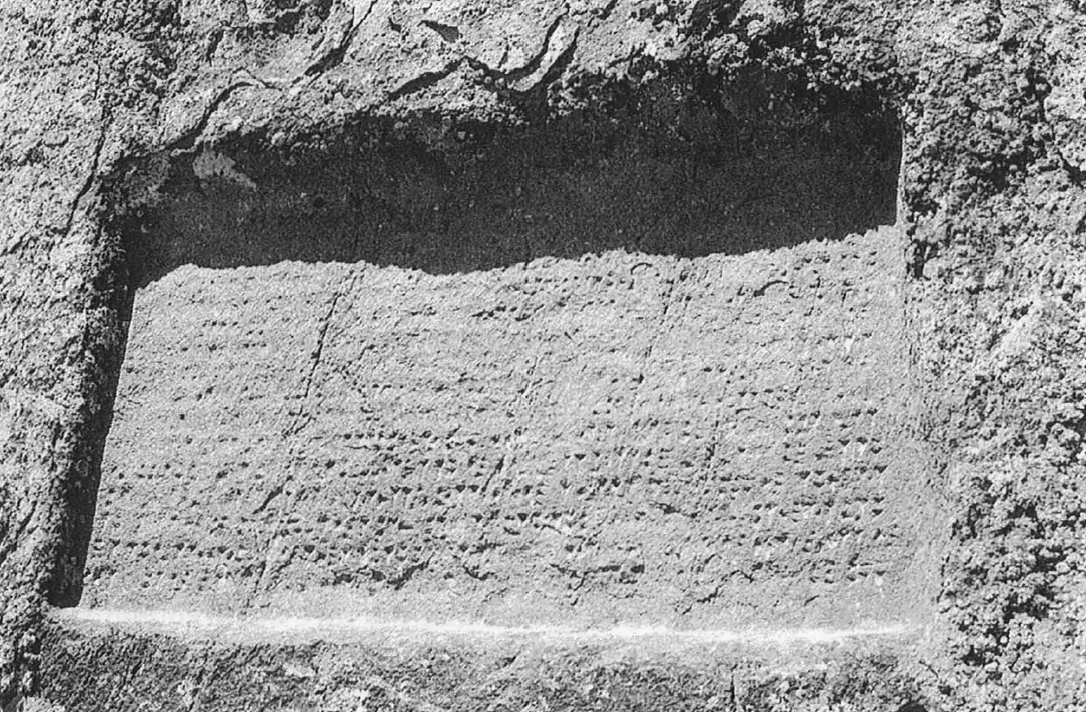

The northern square includes two unequal sectors separated by a straight corridor. The main fire temple complex (fig. 11), built on the north-south axis of the layout, could be reached from both the southeastern gate reserved for the king and from the northern entrance used by pilgrims. The south entrance takes the shape of a deep eyvān (S) in the middle of which lies a podium of polished blocks of stone with stairs (fig. 12). Beyond the south eyvān is a large chāhar-tāq (A), which, according to Huff, was the main place for the sacred fire; it is, indeed, the largest domed hall in the complex measuring 8 m on each side with a cupola 14 m high. Adjacent to this hall, there is a small cruciform, domed hall with a central basin set up on the brick floor of the hall (fig. 13). Kurt Erdmann believed that this was the room for keeping the sacred fire and from which the sacred fire was carried into the large domed hall for official ceremonies. Based on quantities of ashes found in the basin, Huff rightly suggests that the basin was the place to collect the “ashes of the sacred fire to be distributed to the faithful, a tradition which still exists in contemporary fire temples.” (Huff, “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica). The northern approach to the fire temple includes a porch (N) and an archive room (Z) for scribes where 250 bullae with 1200 seal impressions of about 800 different seals were found (Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, pp. 69-70). The temple court (M), 20 x 20 m, bordered by arcades, was possibly a gathering area for priests and pilgrims, which led to the main sanctuary through a vaulted corridor (I). Remains of humble mud-brick structures on the west side of the vaulted corridor might have included a depository room where pilgrims could leave their offerings; a number of votive plaques of gold, silver, and bronze were found there. The eastern sector of the complex was occupied by a small cruciform room (X) where traces of a stone fire altar were found, and a square building with an inner courtyard and pillars (E) which has been interpreted as a depot or treasury. Finally, there is a group of small squared and domed rooms (C and D) where some Sasanian coins were found, which included niches that might have housed royal treasures.

The West Complex, separated from the main fire temple by the north-south corridor (KO1), was a second fire temple with its own subsidiary structures. The West Complex consists of two rectangular pillared halls with round pillars in stone and fired bricks (fig. 14), leading to a cruciform chamber at the northern end of the Complex, where traces of a fire altar were found. The domed, cruciform building (PG) with the rest of the western sector buildings served as service and banquet rooms as a great number of potsherds and organic materials were retrieved in that area. Rudolf Naumann points to a similarity of the West Complex to the pillared hall at Tepe Mil (Naumann, “Tepe Mill, ein Sassanidischer Palast,” pp. 76-77).

The fire temple of Atūr-Gūshnasp fell at the time of the invasion of a Byzantine army led by Heraclius who sacked the temple in A.D. 626 (for the mention of the event in primary sources, see Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, p. 318; and Huff, “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica).

Takht-e Suleiman after the Sasanians: No trace of any immediate re-occupation of the sacred site has so far been found. The demise of the Sasanians brought a long period of oblivion to the ruined fire temple of Atūr-Gūshnasp, the original name of which must have been forgotten in the meantime. Abū Dūlaf’s description of the place infers that the fire was still burning and respected in the tenth century, but archaeological excavations hardly support that. Instead, the site seems to be re-occupied by a series of modest structures that can be dated, based on ceramic finds, to the 10th to 12th centuries. The lush vegetation and beautiful environment of Takht-e Sōleymān attracted Mongol Ilkhāns of Persia, in particular, Abāqā Khan (1234-1282), to restore the Sasanian palace and build a number of structures along the western edge of the lake for his summer sojourn (fig. 15). The Mongols, who were fundamentally horse-riding nomadic people, were attracted by places that could offer sufficient pasturage for their cavalry horses and Takht-e Sōleymān and its region offered plenty of meadowlands.

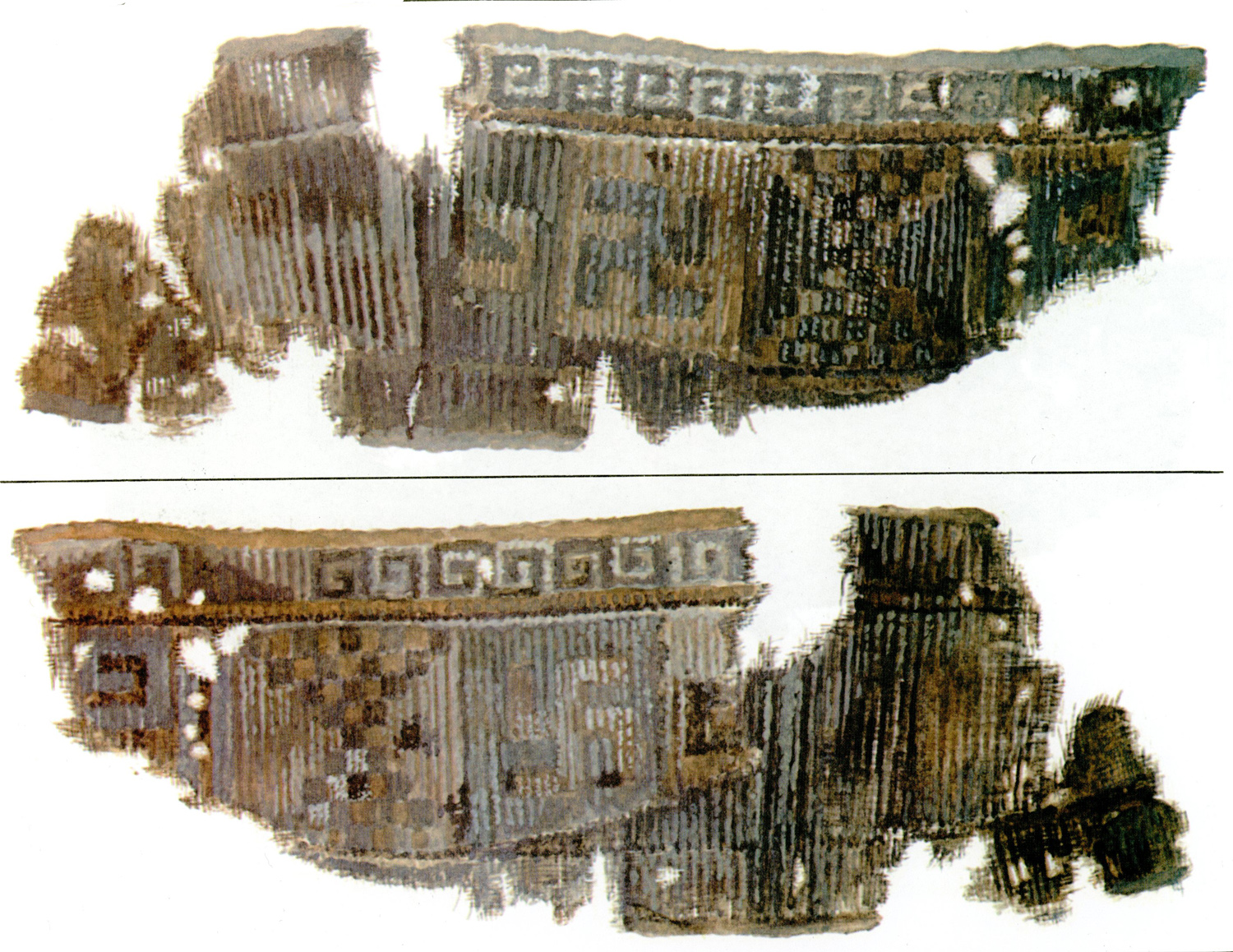

The Sasanian palace with its eyvān was restored and redecorated with glazed tiles depicting anthropomorphic and geometric motifs. The Ilkhān’s architects altered the west end of the palace by adding a large square hall with a wooden roof and two lateral octagonal rooms, each with eight deep recesses or niches surrounding a domed area (figs. 16 and 17). The rooms differ in their design and content. The North Octagon was equipped with benches along the walls and wide windows providing a splendid view of the valley; the South Octagon possibly accommodated bedrooms for the inhabitants or guests of the palace (Huff, “The Ilkhanid palace at Takht-i Sulayman,” p. 104). The interior of the South Octagon was decorated with colorful glazed tiles depicting human figures, and animals. Moreover, a large number of tiles bear poems and they were all manufactured in Kashan (for an art-historical study of the tiles, see Masuya, The Ilkhanid Phase of Takht-i Sulaiman, vol. 1, ch. 4, pp. 224-561; for the inscribed tiles with Persian poems, see Ghouchani, Ash’ār-e farsi-ye kāshihā-ye Takh-e Sōleyman). Some tiles depict figures of dragons and phoenixes; others show riders playing chōwgān (polo). The excavated remains suggest that the squinches in the niches of the South Octagon were decorated with stucco muqarnas (Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, p. 93; Harb, Ilkhanidische Stalaktitgewölbe, pp. 19-42 ). The restoration/remodeling of the Sasanian palace with its great eyvān had been in progress since 1271 as indicated on inscribed wall tiles. As Huff suggests, “three years later in 1274 Abāqā’s grandson Ghāzān was brought there at the age of three to be raised by the Great Lady Būlūghān Khātūn, Abāqā’s favorite wife, at which date the palace must have been fully functional” (Huff, “The Ilkhanid Palace at Takht-i Sulayman,” p. 97).

The plan of the Ilkhanid summer palace approximately follows that of the Sasanian building. A series of arcades bordered the lake; the main fire temple complex to the north of the lake was transformed into a spacious audience hall. The ruins of the fire temple were used as a substructure for a large throne room with a dome. A large square, four-columned hall of approximately 12 m, a ruined mosque, and small houses are the remains of the Ilkhanid construction activities in this sector of the site. With the abandonment of the site after the Sasanian period, the water channels of the spring were no longer maintained; the lake’s water overflowed and deposited thick layers of sediment on its edges. As a result, the surface around the lake, particularly on the north side, raised up about 1.5 m. between the seventh and thirteenth centuries. Because of this difference in height, the Ilkhanid throne room was reached by means of a freestanding staircase placed on the axis of the former south eyvān of the fire temple complex, the ruins of which were demolished to make room for a larger, monumental eyvān with a span of 17 m. On the west side of the lake, a large, square four-columned hall, 20.5 x 20.5 m, was erected; the hall, built in stone, was most probably covered with a cupola (fig. 18). Donald Wilber erroneously thought these four-columned halls were of Parthian date (Wilber, “The Parthian structures at Takht-i-Sulayman,”); later investigations have shown that both structures were built in during the Ilkhanid occupation of the site (Naumann, Huff, Kleiss, “Takht-i Suleiman und Zendan-i Suleiman,” pp. 713-716; Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, pp. 97-102). In the area to the north of the main fire temple, Yussef Moradi uncovered another smaller, four-columned hall that has been dated to the late fourteenth century or to a period after the abandonment of the site by the Ilkhans (Moradi, “Baznegari dar kārbari va gāhnegāri-ye banā-ye chāhārsotuni shomāl atashkadeh-ye Takht-e Sōleymān,” pp. 159-164).

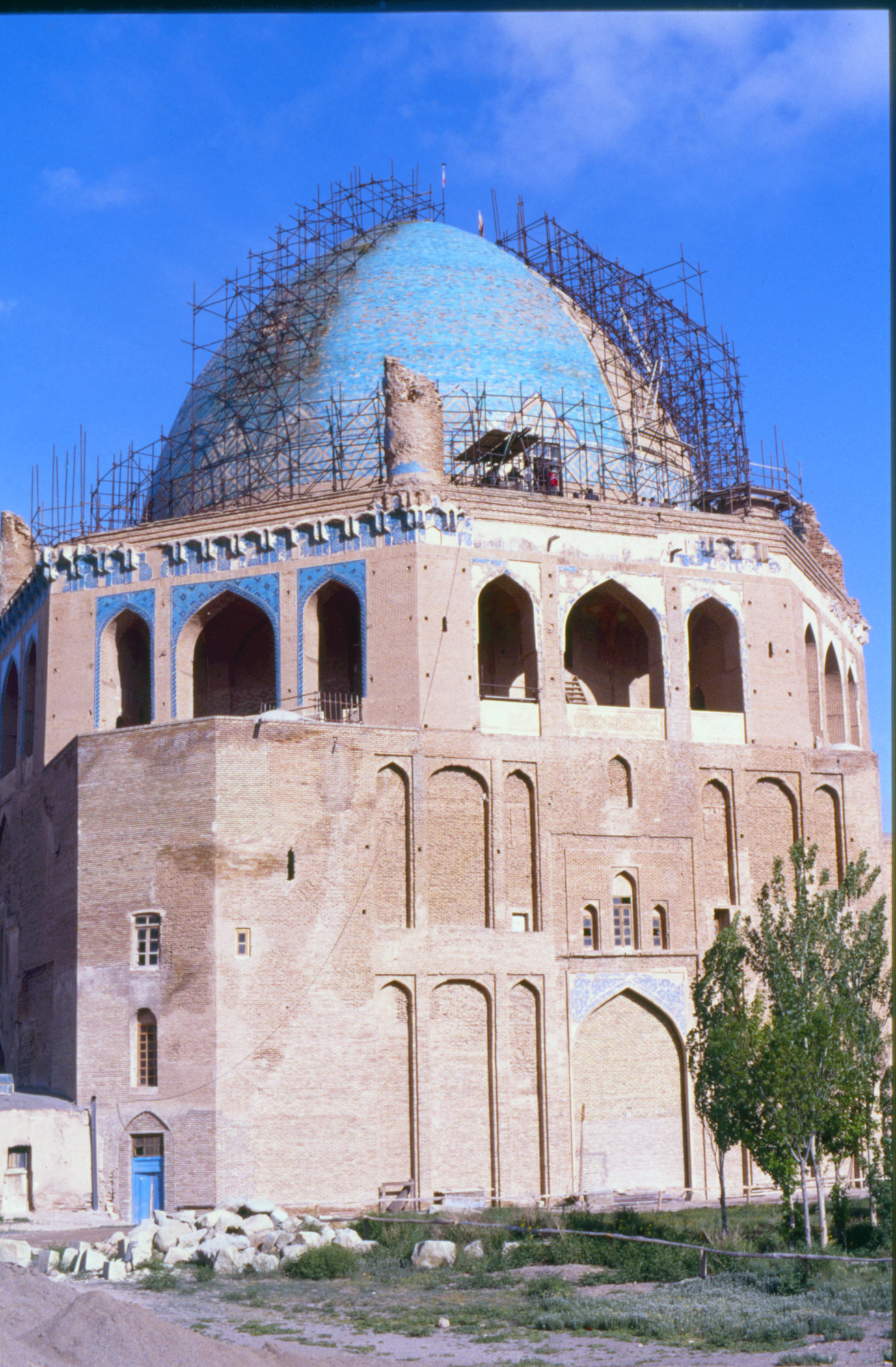

The Ilkhanid Sūqūrlūq had a large gate in the south, for the construction of which the Ilkhān’s architects had to construct a ramp outside the fortified wall. They removed the second bastion to the left of the Sasanian southeast gate in order to broaden access through the new gate. The inner façade of the south gate, now completely destroyed, has been carefully studied and documented. Beyond the gate was an inner room that opened onto an oblong forecourt, 23.5 x 30 m; a second forecourt, 14 x 24 m, connected the entire passageway to the palace area by means of a large eyvān overlooking the lake. The ultimate abandonment of the site took place after the decline of the Ilkhans of Persia, in the fourteenth century. One of the last Ilkhans, Üljāïtū (r. 1304-1316), known as Sultan Mohammad Khōdābandeh after his conversion to Islam, was attached more to his newly founded magnificent mausoleum at Sulātniyeh (150 km east of Takht-e Sōleyman), which offered excellent pasture lands. Sūqūrlūq was gradually forgotten. Almost a hundred years later, the name Takht-e Sōleymān appears for the first time as a place where Shah Ismail spent some time camping and hunting three times, in 910/1504, 911/1505, and 918/1512, (Ja’fari, “Takht-e Sōleymān yā Sūqūrlūq,” pp. 84-85, 87). Later Safavid kings do not seem to have shown any interest in visiting the ruins, particularly after the change of capital from Tabriz to Isfahan by Shah Abbas I.

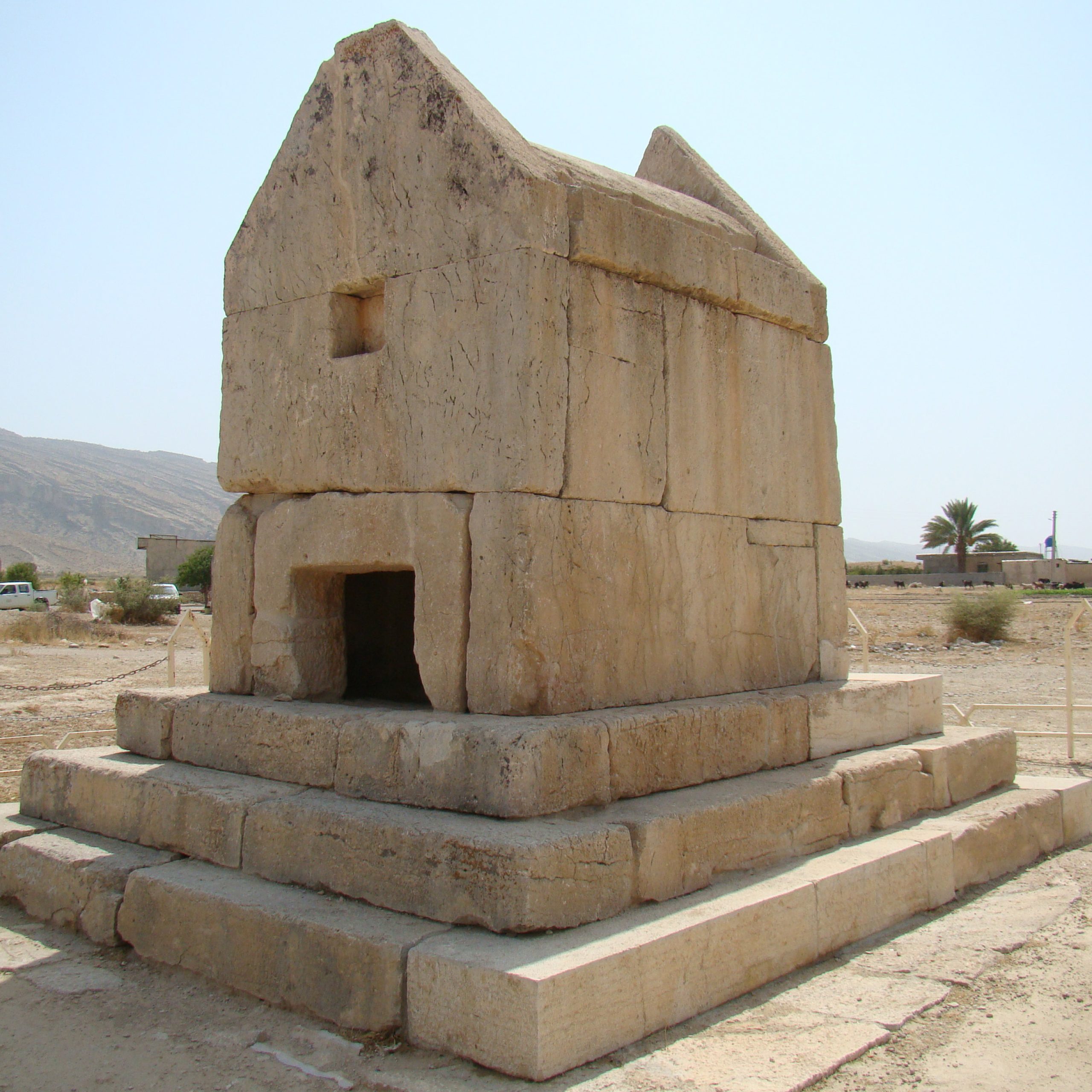

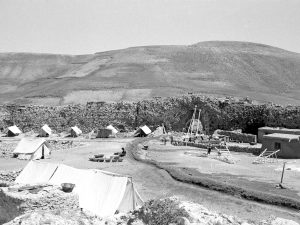

Fig. 1. Takht-e Sōleymān. General view of the site from the east in 1990. In the background the carter of the mount known as the Zendan-e Solymān is visible (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 2. The plan of Takht-e Sōleymān in the Sasanian period (after Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, plate 2)

Fig. 3. Takht-e Sōleymān. The Sasanian wall of the site. The outer shell is in ashlar blocks set in header and strecher while the inner shell, visible at the place of one of the ruined semi-circular towers (at left), is in rubble masonry (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 4. Restoration of the southeastern gate with the German Archaeological mission’s tents in 1970 (photo: M. Mousavi)

Fig. 5. The southeastern gate before restoration in the summer of 1970 (photo: M. Mousavi)

Fig. 6. The southeastern gate after restoration, September 1994 (photo A. Mousavi)

Fig. 7. View of the surviving northern pier of the Great eyvān (the Western eyvān) in 1970 (photo M. Mousavi)

Fig. 8. View of the Great eyvān (the Western eyvān) from the south in 1994 (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 9. Vaulted hall WF adjacent to the Great eyvān in 1998. At the end of the hall is the entrance to vaulted hall WD (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 10. Vaulted corridor WB adjacent to the Great eyvān in 1998 (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 11. Takht-e Sōleymān. The main fire temple complex (after Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, fig. 24).

Fig. 12. Remains of the south eyvān of the fire temple complex in 1994. The group of people right is standing on the floor of the Sasanian period, some 70 cm below. The whole area had been concealed under a thick layer of limestone deposit left by repeated overflooding of the lake (photo: A, Mousavi)

Fig. 13. The brick basin that once kept the sacred fire or contained its ashes (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 14. The pillared hall in the West complex in 1998 (photo: A. Mousavi)

Fig. 15. The plan of Takht-e Sōleymān in the Ilkhanid period (after Naumann, Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman, plate 3)

Fig. 16. Excavation of Ilkhanid remains to the south of the Great eyvān in 1970 (photo: M. Mousavi)

Fig. 17. Excavation of the north octagon near the Great eyvān in 1970 (photo: M. Mousavi)

Fig. 18. One of the column bases in the four columned hall of the Ilkhanid period. Mahmoud Mousavi (right) and Aziz Asheghi (left), August 1970 (photo: M. Mousavi)

Archaeological Exploration:

Medieval travelers and geographers described the site as early as the 10th century (for a list of primary sources, see Schippmann, Die iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, pp. 318-325).

Robert Ker Porter, the British traveler, rediscovered the site in his travels in Iran in August 1818. Ker Porter recorded the impression of his visit as follows (Ker Porter, Travels, vol. 2, p. 557):

It [Takht-e Sōleymān] stands near the foot of a long line of mountains, where, at the base of one of them, rises an extensive elevation of rather an oval form ; and on the smmit of that minor hill the chief part of the city has formerly been erected. The remains of walls and towers still extend along its brow. They are built of hewn stone, and towards the south, and eastern faces of the rock, are yet very lofty. The towers are all solid, and stand at unusually short distances from each other. Four gates lead into the place; each formed by a small circular arch, flanked by massive turrets. No writing, nor remnant of a tablet is perceptible on any of them; a date, therefore, cannot be traced that way ; but from the style of these gate-ways and their whole connecting line of defence, I should assign the character of this city’s military architecture to an age much anterior to many of the ruins within the walls. In the very centre of this embattled hill, lies a small oval lake of most singular appearance, and which the people declare to be unfathomable in the middle. Its length is sixty yards, its breadth thirty. The water, from its great depth and clearness, presents a surface of the most beautiful emerald green.

Ker Porter goes on to describe the petrifying characteristic of the water that had left solid deposits in the course of time. He rightly concludes that “the whole hill, in the centre of which the lake now lies, was originally, and by the action of ages, the offspring of this very water…” (Travels, vol. 2, p. 558). His passionate account of the ruins betrays his difficulties in putting them in an accurate historical context.

Later, Henry Creswick Rawlinson visited the ruins in November 1838. Rawlinson’s visit and his writings on the site and its identification are noteworthy here. In his 1840 article, he presents a thorough description of the ruins and indicates his idea about the identification of the site as Median Ecbatana (“Notes on a Journey from Tabríz,” pp. 46-47):

The first view of the ruins of Takht i-Soleïmán is certainly striking… From a distance they present to view a grey hoary mass of crumbling walls and buildings, encircling a small piece of water of the deepest azure, and bounded by a strong line of wall supported by numerous bastions. A nearer inspection shows the ruins, perhaps, to less advantage; but I confess, to me it was fraught with much interest, for at every step, I met with fresh evidence to confirm me in the belief that I now beheld the great capital of Media.

Rawlinson is the first visitor of the site to have recognized the ruined remains of the Sasanian fire temple situated to the north of the lake (“Notes on a Journey from Tabríz,” p. 51):

There is one particular mass however, situated on the northern side of the square which demands more attention. Porter considered it to be a ruined hammam, or bath, which scarcely deserves notice; but, after a minute examination, I see no reason to doubt its representing the ancient Fire Temple of the province of Azerbijan, which, before the rise of Islam, is known to have been one of the most holy places in Persia. The obscure history of the temple I shall endeavor to illustrate in the memoir, and here, therefore, confine myself to a description of the ruin…Amid the mass of crumbling rubbish it was not very easy at first to ascertain the original design of the building; but after some trouble I succeeded: the temple has been a square edifice of 55 feet.

In his “Memoir on the Site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” Rawlinson discusses in length all the available sources pertaining to the historical geography of the region. His principal goal is to identify the situation of the ancient capital of Media Atropatene, Ecbatana. For this, he proceeds with the “connexion of the early Arabes with the Byzantines; to trace up afterwards the fortunes of the city through the flourishing ages of the Roman and Greek empires: and thus finally arrive at the dark period of the Median dynasty, where fable is intermixed with history, and glimmerings of truth can only be elicited by careful and minute examination” (“Memoir on the Site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” p. 65). For Rawlinson, there are two Ecbatanas, one in southern Media (possibly at Hamadan), and the other in the north, which he identifies as Ecbatana of Deioces or the Ganzaca of the Sasanians or the Shiz of the Arabs. Once the connection is established, he is convinced that the site represents the ancient capital city of the Medes (“Memoir on the site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” p. 128):

I believe the mound of Takhti-Soleïmán to have been first surrounded with defences by the Median Dejoces, and the area within the walls, which was amply sufficient for the noblest palace that kingly splendour could devise, to have been reserved by him for his exclusive residence. The great mass of the city, as Herodotus declares, was in the plain below, and this distinction between the palace and the city was preserved as long as the place continued to be inhabited.

Later historical studies and archaeological research have disapproved of Rawlinson’s identification of the site with the capital of the Medes, of which one can refer to Etienne Quatremère’s Mémoire sur la ville d’Ecbatane in Mémoires de l'Institut de France, vol. 19, 1851, pp. 419-456, as well as Avraham Williams Jackson who, in his 1909 visit, gives an excellent overview of the ruins complemented by Middle Persian sources in connection with the fire temple (Persia. Past and Present, ch. XI, pp. 124-143).

In 1937, Arthur Upham Pope and Donald N. Wilber reached the site and carried out a photographic survey of the ruins on behalf of the American Institute for Iranian Art and Archaeology. They erroneously suggested that Takht-e Sōleymān was the site of Parthian Phrāaspa mentioned in Roman sources narrating Marcus Antonius’ Parthian War, 33-40 B.C. They concluded that (Pope, “Preliminary Report on Takht-i-Suayman,” p. 89):

With our present knowledge, the history of the citadel cannot be traced to a period preceding Antony. The Institute's expedition reports that the oldest architectural remains are Parthian… And that the Atur-Gushnasp Fire Temple was to be sought elsewhere… On the other hand, the famous fire of Adhargushnasp, "the fire of the stallion," described in the great Bundahish and frequently mentioned elsewhere, is ascribed by tradition to very ancient times, and its name, or corruptions thereof, is mentioned in direct association with Shiz… However, the Iranian tradition (in contrast with that of the Arabs) is consistent in associating the sacred fire with the immediate vicinity of Lake Urmiya, and, indeed, Firdawsi's own account would refer to that region rather than the region of Takht-i-Sulayman, so that, for the present, no definitive localization of the fire at the Takht can be made.

In the years preceding the beginning of archaeological excavations at Takht-e Sōleymān, Lars-Ivar Ringbom, the Finnish art historian, wrote extensively on the identification of the site as the place where the Chalice of the Holy Grail was kept after the sack of Jerusalem in 614 by Khosrow II. Ringbom believed that the imagery of a seventh-century silver salver (now in the Hermitage Museum) depicted the capture of the Castle of the Magi in Shiz. He discusses in length that the celebrated Takht-e Taqdis of King Khosrow II was at Takht-e Sōleymān (Ringbom, Paradisus Terrestris, pp. 320-323, 373, fig. 192; pp. 442-443 of the English abstract). In his Graltempel und Paradies, he discusses another plate in bronze (in the Berlin Museum) with the depiction of Khosrow’s throne or Takht-e Taqdis at Shiz (Graltempel und Paradies, p. 52, fig. 15; reproduced in R. and E. Naumann, Takht-e Suleiman, pp. 22-23, figs. 8-9; for a general discussion on the identification of the Grail Castle, see Matthews, The Grail. Quest for the Eternal, pp. 20-31). For Ringbom, the bronze plate in Berlin represents the temple around the sacred lake, the symbol of Anahita, whose worship was connected to the cult of fire (Graltempel und Paradies, p. 288). Rudolf Naumann seems to be of the same opinion as he writes (R. and E. Naumann, Takht-i Suleiman, p. 22):

Welche Bedeutung der See im zoroastrischen Feuerkult hatte, geh aus den literarischen Quellen über Shiz leider nicht hervor. Es ist nicht ausgeschlossen, dass hier die Zendan-Überlieferung eine ausschlaggebende Rolle spielte. Hier wie dort lag das Wasser im Zentrum. Eng verbunden mit dem Feuerkult war tatsächlich die Verehrung der Anahita, der Göttin der himmlischen Wasser; im Avesta ist, Ardvi Sura anahita eine Quelle, die auf dem mythischen Berg Hukairja entspringt. Wenn sich diese Sage auch auf den gesamten Weltkreis bezieht, so mag man zunächst im Zendan, später auf dem Berg in Shiz ein Abbild dieser sagenhaften Weltlandschaft gesehen haben. Und wenn im, Bundahishn (Weltentstehungsgeschichte der Parsen) gesagt wird, aus einem kleinen Hügel habe sich der Weltberg herausgebildet, so erinnert dies an das Wachsen von Zendan und Takht durch das kalkhaltige Wasser.

Archaeological excavations began under Hans Henning von der Osten and Rudolf Naumann on behalf of the German Archaeological Institute in 1959 and continued until 1978 (See bibliography. A recent review of the German Archaeological Institute excavations is published in Helwing and Rehmipour, Tehran 50. Ein halbes Jahrhundert deutsche Archäologen in Iran, pp. 92-91; Huff, “Tacht-e Solaiman,” in Tehran 50. Ein halbes Jahrhundert deutsche Archäologen in Iran, pp. 140-145). The results revealed that the site was the royal fire temple of the Sasanian Empire known as Atūr Gūshnasp or the Fire of the Stallion and that the location of Parthian Phrāaspa was to be sought elsewhere. Between 2002 and 2006, Yusef Moradi resumed the excavations at Takht-e Sōleymān on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research. Moradi’s excavations in the area of the north gate of the site yielded some 1300 clay bullae, the full results of which are yet to be published (Moradi, “Gozāresh-e moqadmāti-ye nakhostin fasl az dowr-e sevvom-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenāsi dar Takht-e Sōleymān,”; Amanollahi, “Morūri bar pishin-ye tārikhi, farhangi, pajūheshi-ye Takht-e Sōleymān,” pp. 12-13).

Finds:

Architectural remains of the Sasanian and Ilkhanid periods.

Fifth century B.C. tombs of the Achaemenid period with skeletal remains.

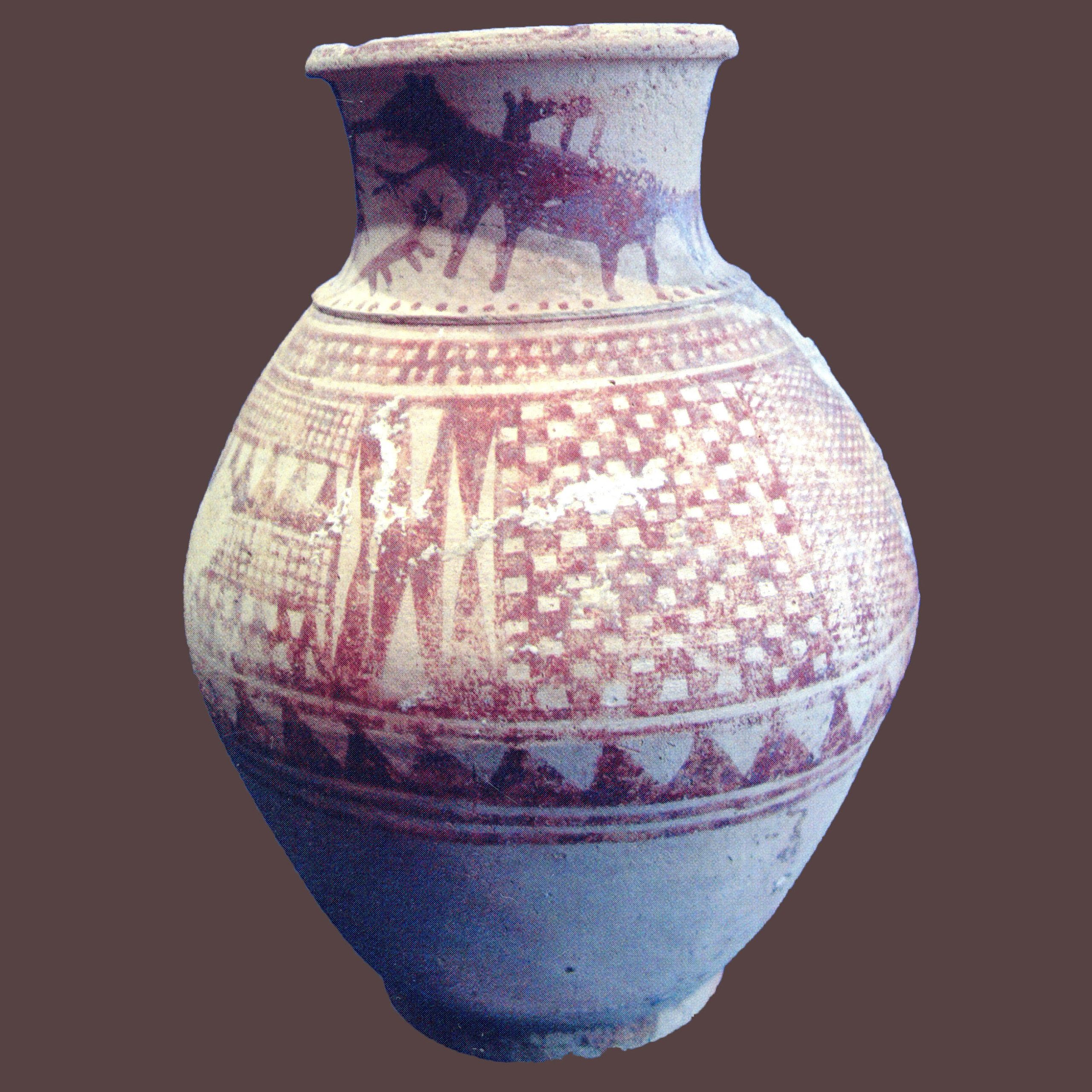

Parthian Clinky or Cinnamon Ware.

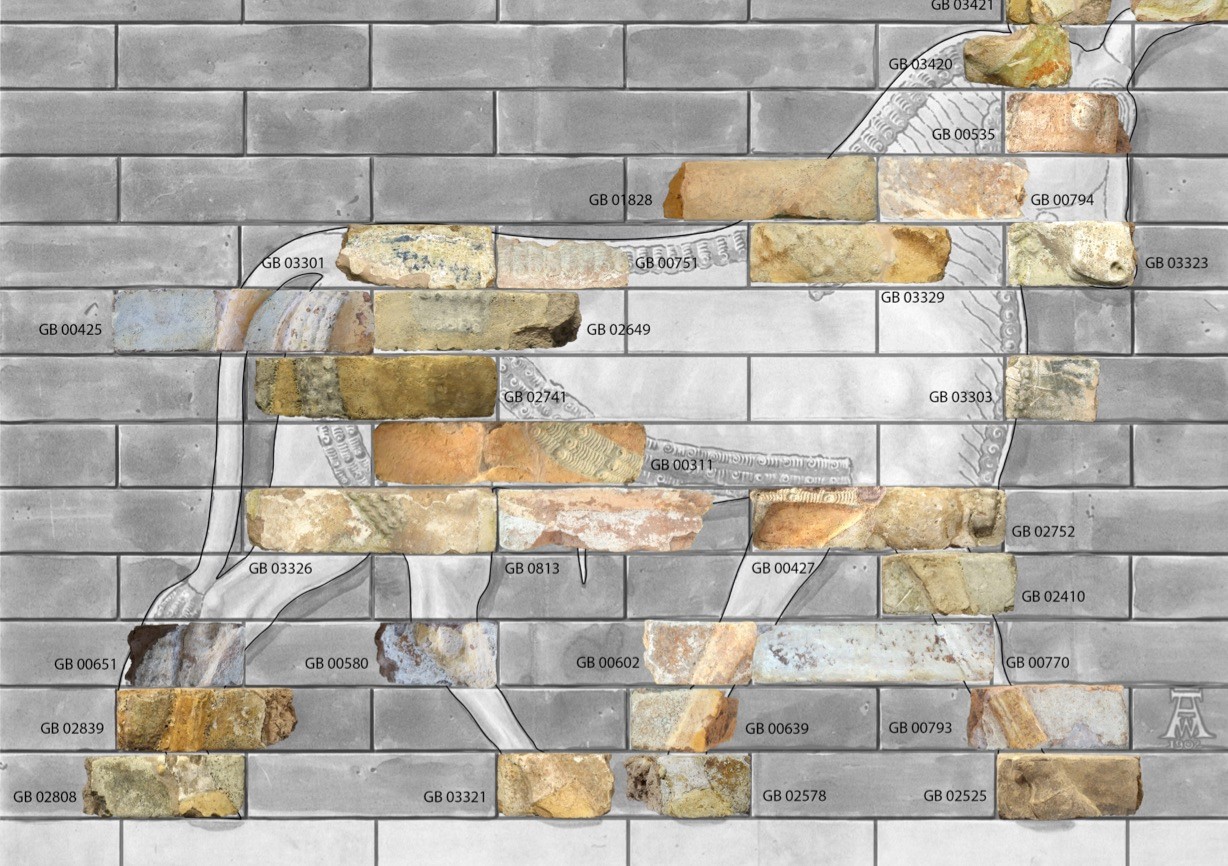

Sasanian structures in stone and rubble masonry; Seal impressions or bullae with Middle Persian texts and animal motifs; gold sheets with the human figure; Sasanian silver coins; Byzantine coins.

12-13th century kilns; glazed tiles, glazed and molded tiles depicting anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs, bearing inscriptions in Persian (often poems); the majority of tiles was produced in Kashan and brought to Takht-e Sōleymān; glazed ceramics such as the so-called Garrus Ware with inscriptions in kufic; ceramic flasks decorated with floral and animal motifs; clay molds for making figurines, calligraphic tiles with the name of religious personalities such as Ali.

Bibliography:

Main excavation reports and studies are in Huff, “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica, at Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, © Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. The following bibliography includes those publications which have been referred to in the text.

Amanollahi, H., “Morūri bar pishine-ye tārikhi, farhangi, pajūheshi-ye Takht-e Soleymān,” Asar, No. 69, 1394 /2015, pp. 1-18.

Bazin, L., “Note sur le turc suġur (soġur?) « marmotte »,” Jornal asiatique, vol. 272, Nos. 3-4, 1984, pp. 284-286.

Boyle, A. J., “Sites and Localities Connected with the History of the Mongol Empire,” Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Mongolists, Ulan Batur, 1972, reprinted in The Mongol World Empire: 1206-1370, Vorarium Reprints, London, 1977, ch. XVI, pp. 75-79.

Hamdullah Mostowfi, The Geographical Part of Nuzhat-al-Qolub composed by Hamd-Allāh Mustawfī of Qazwīn in 740 (1340), translated by G. Le Strange, Gibb Memorial Series, vol. XXIII 2, London, 1919.

Harb, U., Ilkhanidische Stalaktitgewölbe: Beiträge zu Entwurf und Bautechnik, Berlin, 1978.

Helwing, B. and P. Rahemipour (eds.), Tehran 50. Ein halbes Jahrhundert deutsche Archäologen in Iran, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Eurasien-Abteilung, Berlin, 2011.

Huff, D., “Takht-i Suleiman,” Archiv für Orientforschung, 29/30, 1983/1984, pp. 293-295.

Huff, D., “The Ilkhanid palace at Takht-i Sulayman: excavation results,” Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, L. Komaroff (ed.), Leiden and Boston, 2006, pp. 94-110, color plates 5-6, figs. 11-22.

Huff, D., “Tacht-e Solaiman,” in Tehran 50. Ein halbes Jahrhundert deutsche Archäologen in Iran, B. Helwing and P. Rahemipour (eds.), Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Eurasien-Abteilung, Berlin, 2011, pp. 140-145.

Huff, D., “Taḵt-e Solaymān,” Encyclopedia Iranica, at Encyclopaedia Iranica Online.

Ja’fari, Q., “Takht-e Soleymān yā Sūqūrlūq dar zamān-e moqol va ba’d az ān,”Vahid, No. 215, Shahrivar 1356/ Aug.-Sept. 1977, pp. 34-36.

Ja’fari, Q., “Takht-e Sōleymān yā Sūqūrlūq dar zamān-e moqol va ba’d az ān,” Vahid, Nos. 219-220, Āban 1356/ Oct-Nov. 1977, pp. 34-36.

Kniebel, C., Paläodontologische Untersuchung der Skelettfunde vom Takht-i Suleiman, Dissertation, Freien Universität Berlin, 1986.

Matthews, J., The Grail: Quest for the Eternal, London, 1981.

Masuya, T.,The Ilkhanid Phase of Takht-i Sulaiman, part 1, unpublished dissertation, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, 1997.

Minorsky, V., Abu Dulaf Mis’ar ibn Muhalhil’s Travels in Iran, Cairo, 1955.

Moradi, Y., “Gozāresh-e moqadmāti-ye nakhostin fasl az dowr-e sevvom-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenāsi dar Takht-e Sōleymān,” Nāme-ye Pajuheshgāh, No. 2, 1383 /2004, pp. 91-106.

Moradi, Y., “Baznegari dar kārbari va gāhnegāri-ye banā-ye chāhārsotuni shomāl atashkadeh-ye Takht-e Sōleymān,” Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, vol. 50, 2012, pp. 156-166.

Mousavi, M., Rāhnamā-ye Takht-e Sōleymān, Urmia, 1370/1991.

Naumann, R., D. Huff, W. Kleiss, “Takht-i Suleiman und Zendan-i Suleiman. Vorlaufger Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in den Jahren 1963 und 1964”, Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1965-66, pp. 619-802.

Naumann, R., D. Huff, R. Schnyder, “Takht-i Suleiman: Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1965-1973,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1975, pp. 109-204.

Naumann R., Die Ruinen von Tacht-e Suleiman und Zendan-e Suleiman und Umgebung, Berlin, 1977.

Ringbom, L. I., Graltempel und Paradies. Beziehungen zwischen Iran und Europa im Mittelalter, Stockholm, 1951.

Ringbom, L. I., Paradisus Terrestris. Myt, Bild och Verklighet, Helsinki, 1958.

Stahl, A.F., “Reisen in Zentral-und-Westpersien,” Petermanns Mitteilungen, vol. 51, 1905, pp. 4-12.

Schippman, K., Die Iranischen Fuerheiligtümer, Berlin, 1971, pp. 307-357.

Tardieu, M., “Les gisements miniers de l'Azerbayjān méridional (Région de Taxt-e Soleymān) et la localisation de Gazaka,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute, vol. 12, 1998, pp. 249–268.

Sarfaraz, A. A., Takht-e Suleiman, 1347/1968, Tabriz.

Von der Osten, H. H., R. Naumann, Takht-i-Suleiman: Vorläufiger Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1959, Teheraner Forschungen 1, Berlin, 1961.

Wilber, D. N., “The Parthian Structures at Takht-i-Sulayman,” Antiquity, vol. 12, 1938, pp. 389-410.

Williams Jackson, A. V., Persia. Past and Present, London, 1906.