Sardisسارد

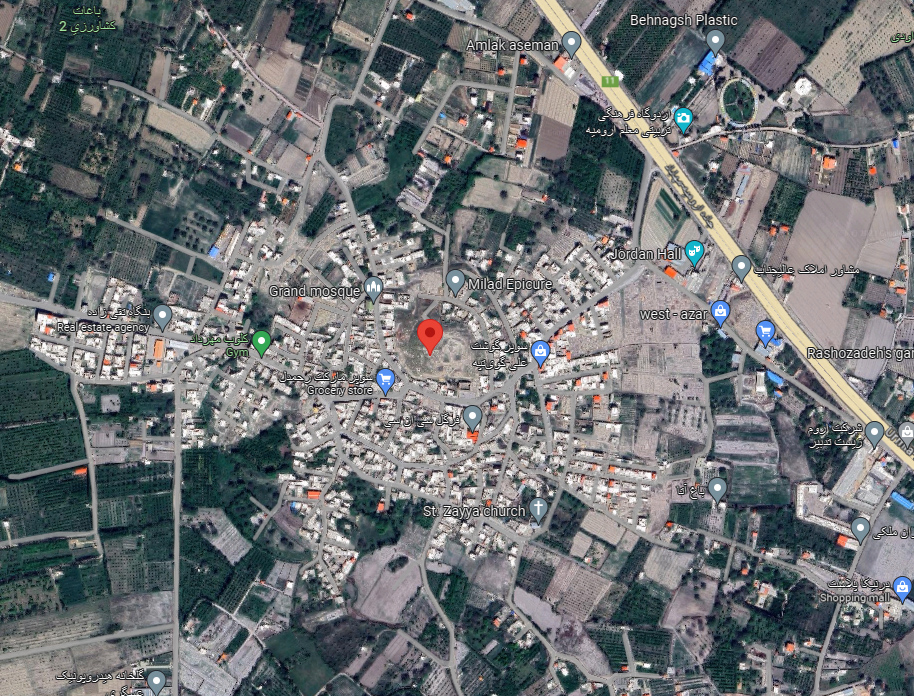

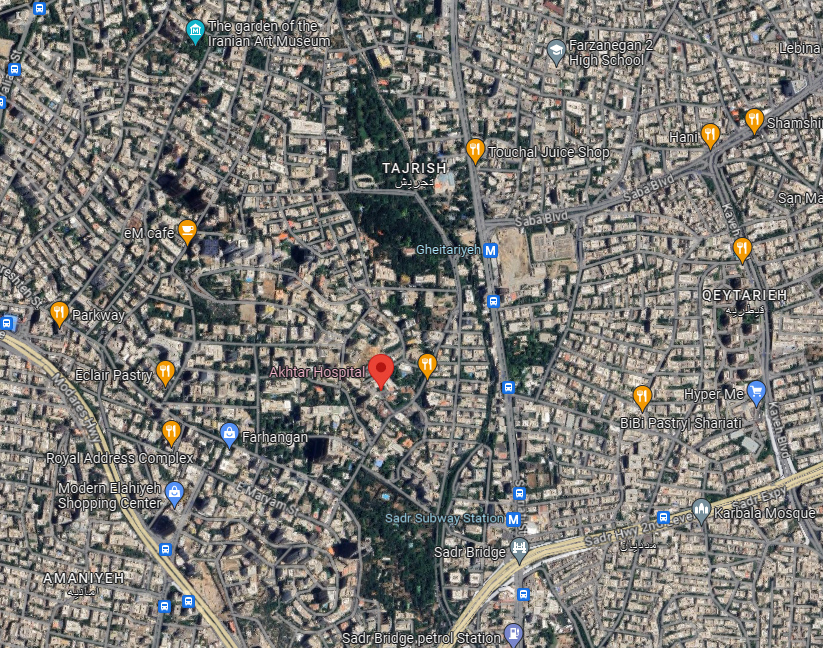

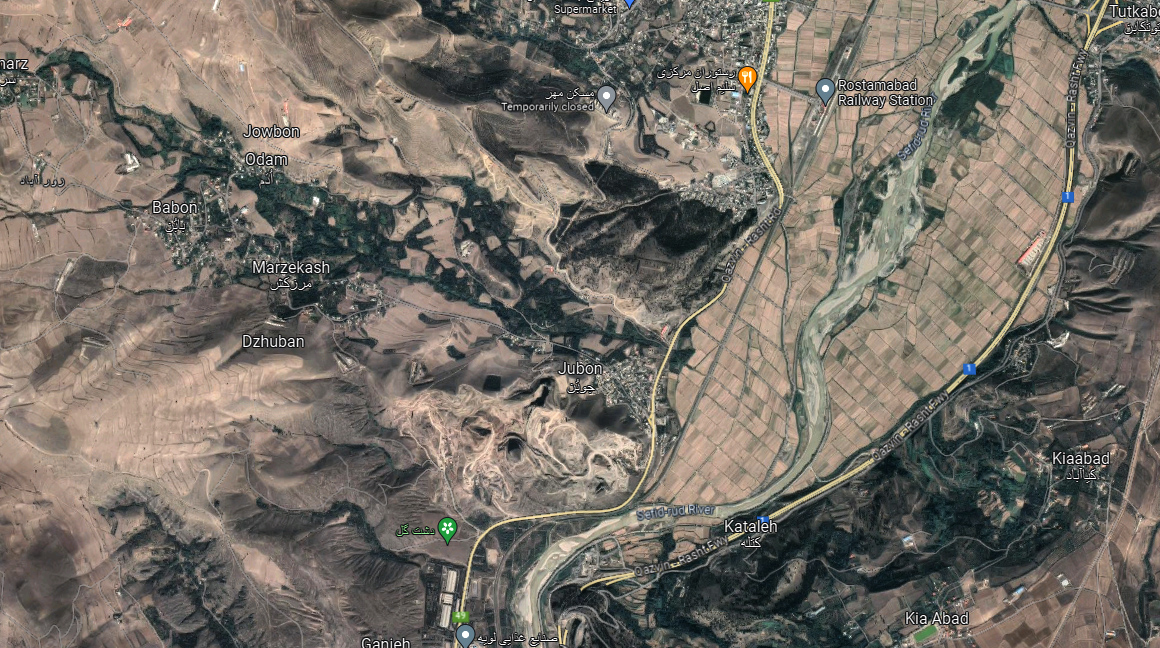

Location: The ruins of Sardis are located near the modern village of Sart in Manisa district, western Turkey.

38°29’18.0″N 28°02’25.0″E

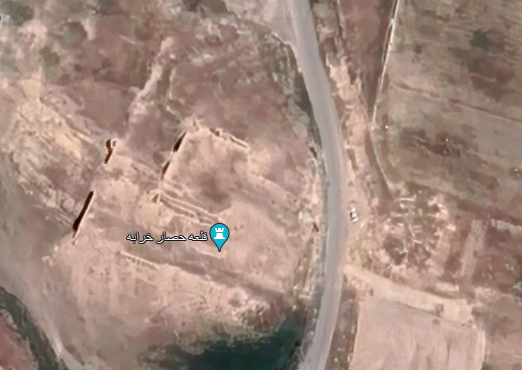

Map

Historical Period

Iron Age, Achaemenid

History and description

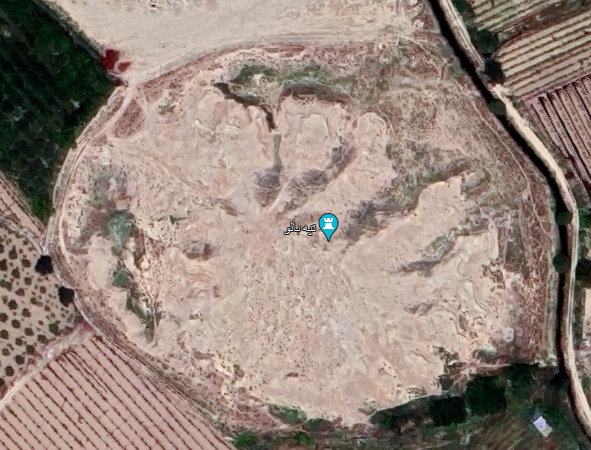

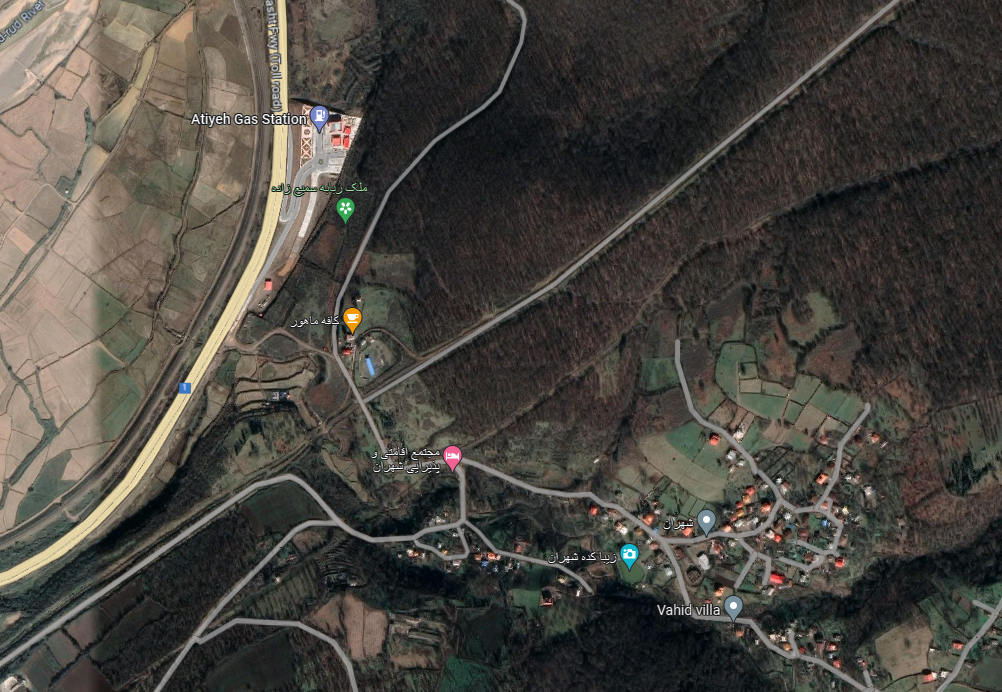

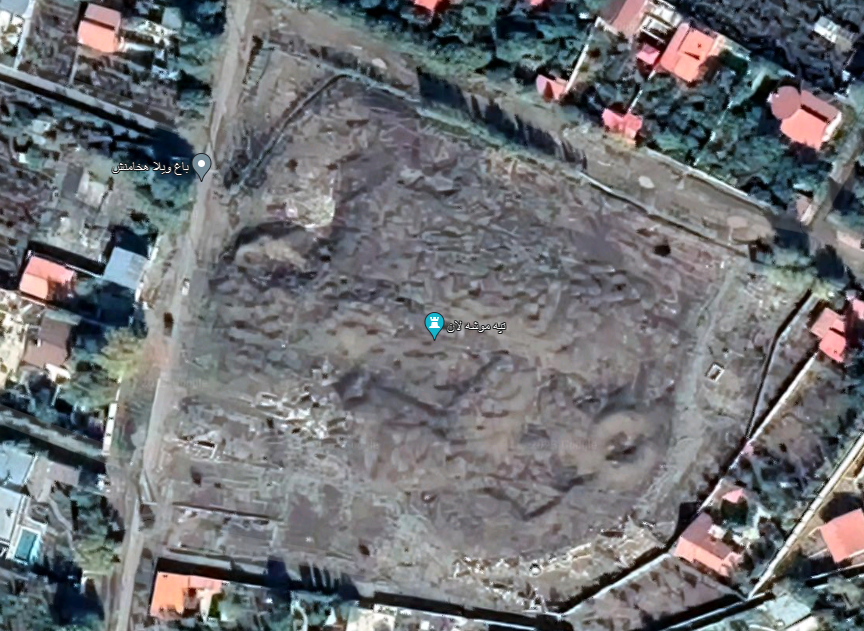

The ruins of Sardis are scattered over a vast area south of the present-day village of Sart, about 75 km from modern Izmir in western Turkey (fig. 1). Sardis was an important site, and its history spans from the Bronze Age to the Ottoman period. It served as the capital of the Lydian Empire during the late Iron Age period and was renowned for its abundant natural resources, particularly gold. According to Greek and Roman mythology, Sardis gold was believed to have been founded by King Midas of Phrygia washing away the Golden Touch in the Pactolus River.

In 547 B.C., Sardis fell to the newly established Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great. This event is recounted in Greek and Roman historical accounts, notably Herodotus' Histories, Book 1. According to Herodotus, the fall of Sardis occurred due to a misinterpretation by Croesus, the Lydian king, who consulted the Oracle of Delphi to determine whether he should march against the Persians following Cyrus' conquest of Media. The Oracle's response was cryptic, stating that if Croesus did so, he would destroy a great empire—a prophecy that ultimately came true for Lydia itself. Recent archaeological excavations have shed light on this event, revealing destruction layers that align with this historical period.

The Achaemenid Persian period (547–334 B.C.) marks a significant chapter in Sardis' history, as the city transitioned from an imperial capital to a satrapy—a provincial administrative center within the Achaemenid Empire—linked by the Royal Road to Susa. This era brought substantial changes to the city, though the archaeological record from this period is relatively limited compared to other periods.

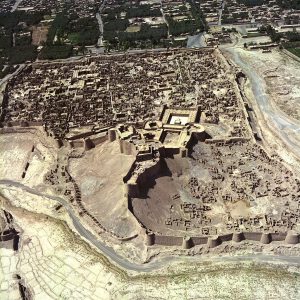

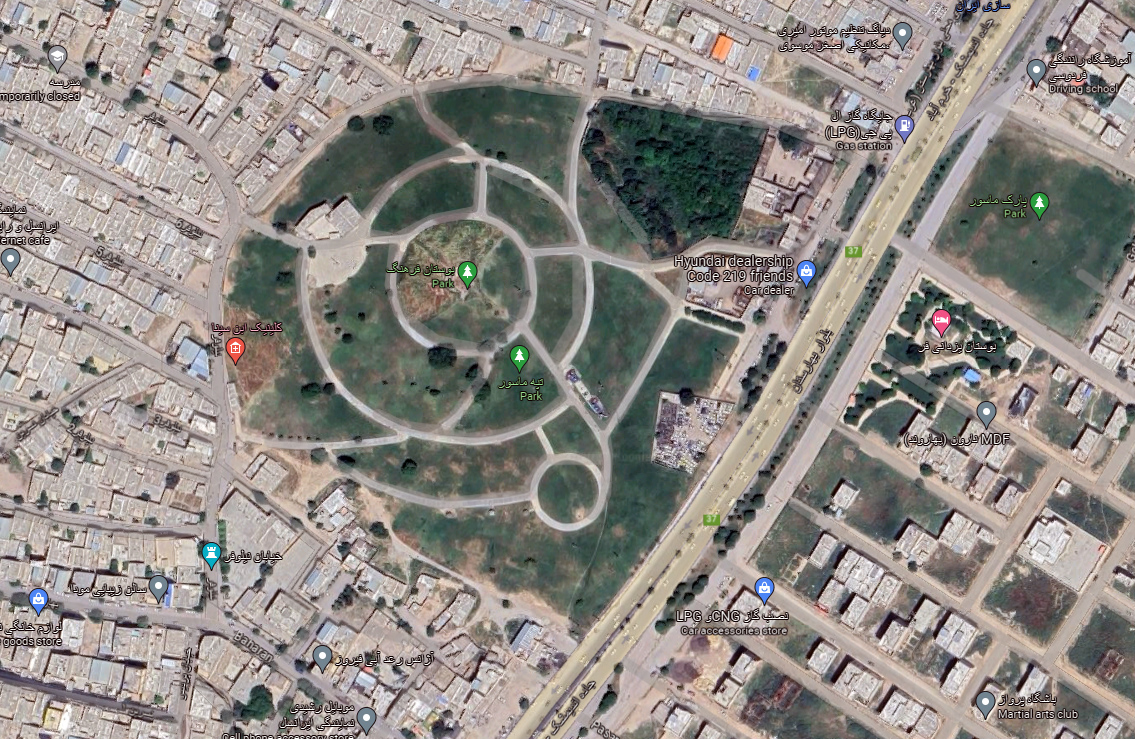

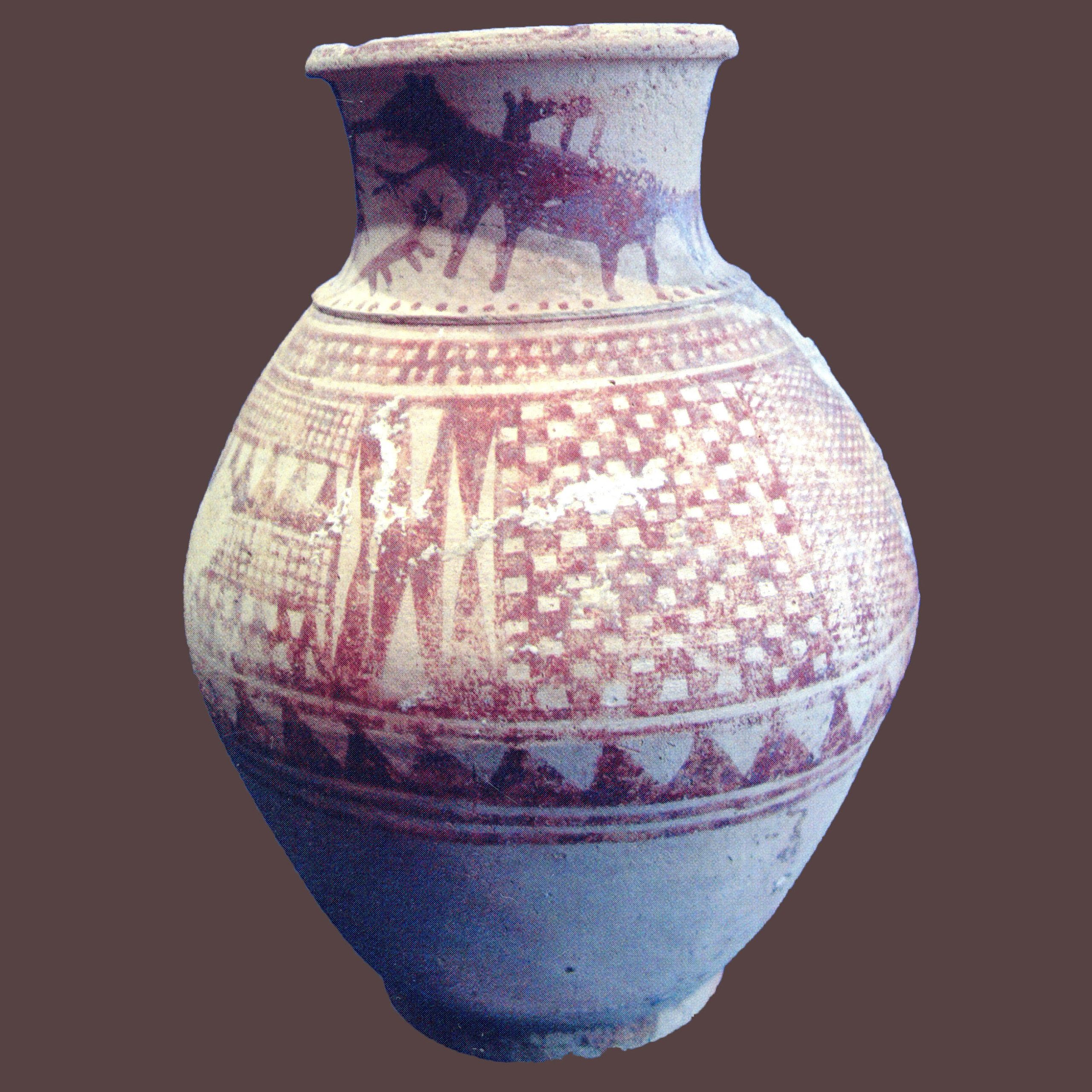

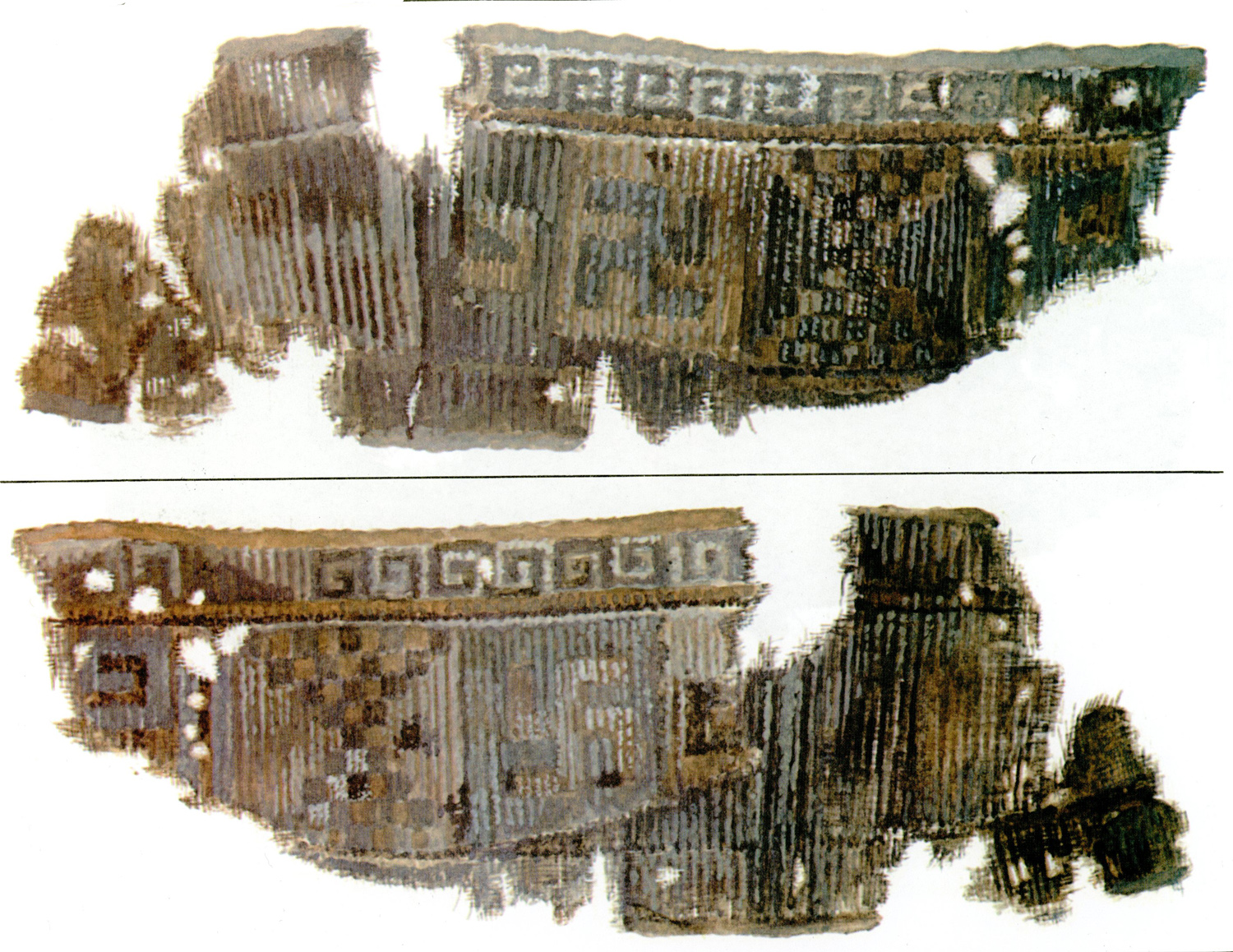

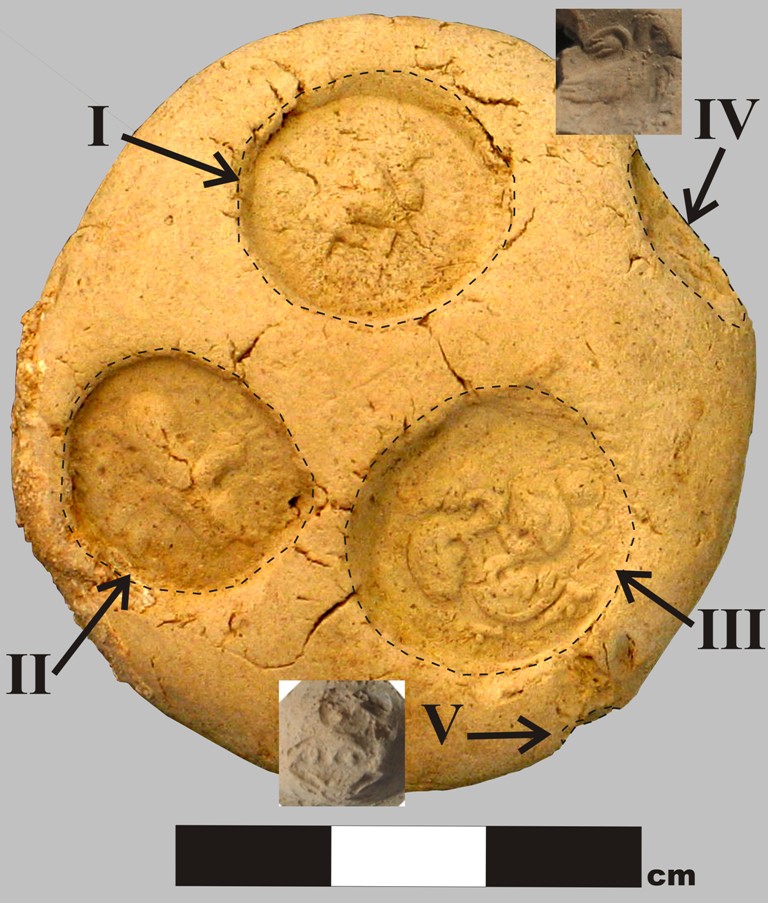

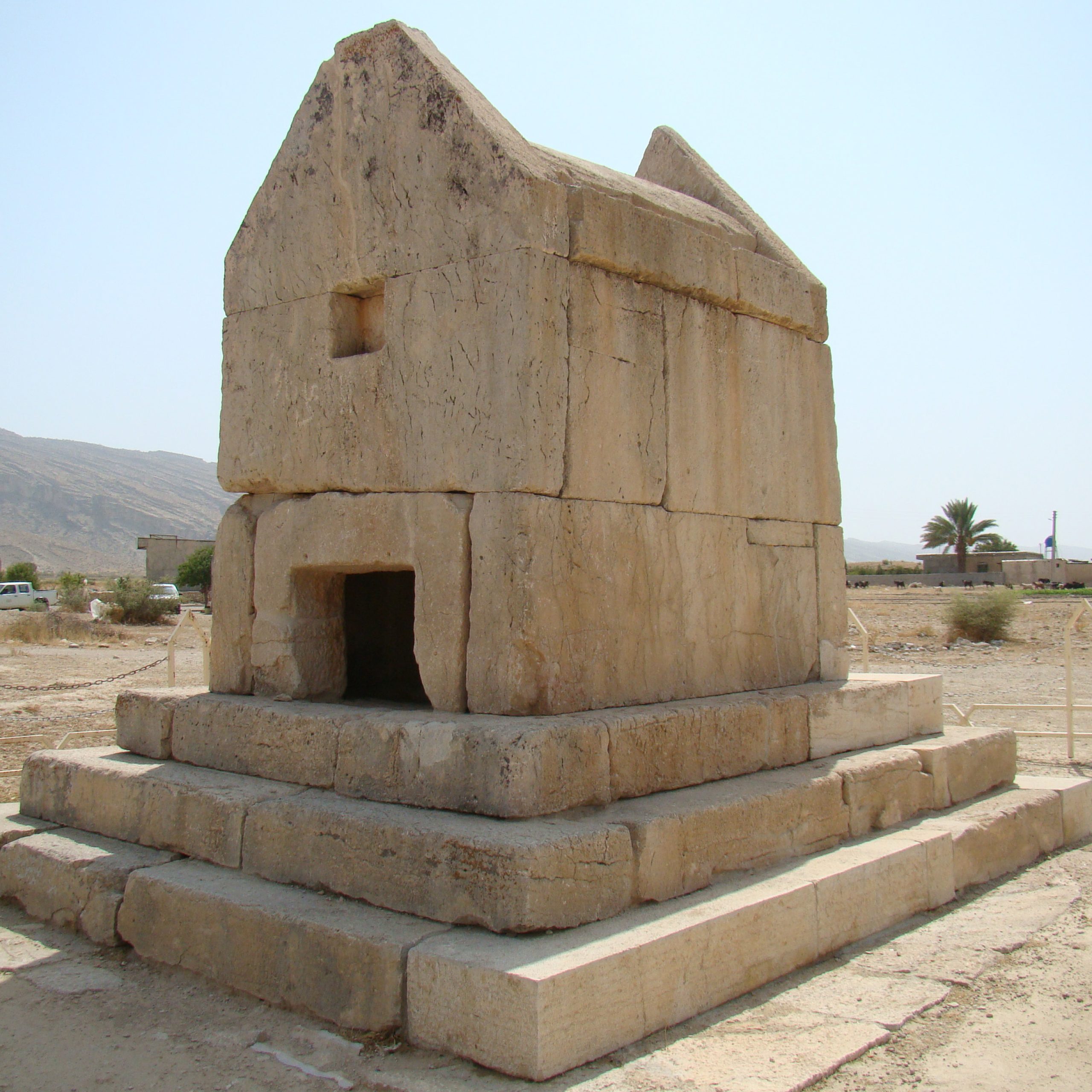

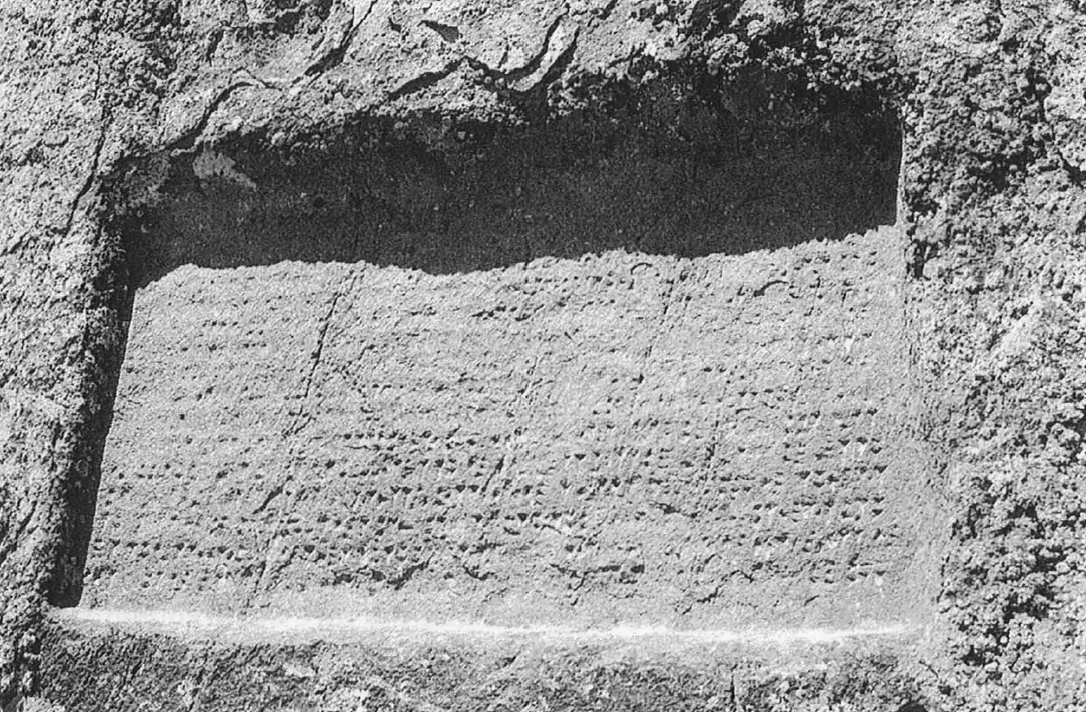

While literary sources emphasize the strategic significance of Sardis during the Persian period, archaeological evidence presents a more nuanced picture. The city center within the walls—once the heart of Lydian Sardis—appears to have been largely uninhabited during this time, with few archaeological materials discovered. The Persian rule may have resulted in the relocation of the inhabitants to other areas. Life outside the city walls continued with evidence of crafts and religious activities, such as bronze working and the worship of Cybele, the mother goddess, near the Pactolus River. Additionally, many tombs in the broader Sardis area date to this period, with the Butler excavations of the cemeteries revealing remarkable examples of Achaemenid jewelry and vessels see below). One of the most famous of these is the so-called Pyramid Tomb (fig. 2), which resembles the Tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae, Iran. The evidence indicates that Sardis underwent a complex transformation during the Achaemenid period. While the city remained an important center, it also adapted to its new role within the Persian Empire. Further archaeological exploration is essential to fully understand this chapter in Sardis's history.

Archaeological Exploration

Systematic archaeological exploration of Sardis began in 1910-1914 and 1922 under the leadership of Howard Crosby Butler. His team made significant discoveries, including the Temple of Artemis and numerous Lydian and Persian tombs. Unfortunately, political instability and Butler's untimely death cut the excavations short in 1922.

Over three decades later, in 1958, a new expedition sponsored by Harvard and Cornell Universities, led by George M. A. Hanfmann, resumed the work. This ongoing program has seen continued leadership by Crawford H. Greenewalt (1976-2007) and currently, Nicholas Cahill. Their research focuses on intriguing aspects of Sardis' past, including the Lydian palace complex, the Sanctuary of Artemis, and the city's transformation during the Persian period.

Excavating Sardis is a complex and time-consuming task due to its layered history. The city boasts settlements from the Bronze Age through the Ottoman period. Despite over 60 years of continuous excavation, only a small portion of Sardis has been revealed, leaving many captivating mysteries waiting to be unearthed.

Bibliography

Bruce, W. “Life Outside the Walls Before the Seleucids,” in Spear-Won Land: Sardis from the King’s Peace to the Peace of Apamea (Wisconsin Studies in Classics), edited by A. Berlin and P. J. Kosmin, Madison, Wisconsin, 2019, pp. 44–49.

Cahill, N. D., “Sardeis’te Pers Tahribi / The Persian Sack of Sardis,” in Lidyalılar ve Dünyaları / The Lydians and Their World (Yapı Kredi Kültür yayınları 3055), edited by N. D. Cahill, İstanbul, 2010, pp. 339–361.

Cahill, N. D., “Sardis in the Persian Era,” Actual Archaeology: Persians in Anatolia, vol. 6, 2013, pp. 55–65.

Cahill, N. D., “The Satrapy of Lydia,” in Persler Anadolu’da: Kudret ve Görkem / The Persians: Power and Glory in Anatolia (Anadolu Uygarlıkları Serisi = Anatolian Civilizations Series 6), edited by K. Iren, Ç. Karaöz, and Ö. Kasar, Istanbul, 2017, pp. 308–329.

Cahill, N. D., “Inside Out: Sardis in the Achaemenid and Lysimachean Periods,” in Spear-Won Land: Sardis from the King’s Peace to the Peace of Apamea (Wisconsin Studies in Classics), edited by A. Berlin and P. J. Kosmin, Madison, Wisconsin, 2019, pp. 11–36.

Cahill, N. D., “Recent Fieldwork at Sardis,” in The Archaeology of Anatolia, Volume III: Recent Discoveries (2017-2018), edited by S. R. Steadman and G. McMahon, 2019, pp. 122–138.

Cahill, N. D., “The Lydian Palaces at Sardis in the Light of New Research,” Türk Arkeoloji ve Etnografya Dergisi, 2023, pp. 11–41.

Cahill, N. D. et al., “A New Find of Croeseid Coins from Sardis,” Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Forthcoming.

Cahill, N. D., and J. H. Kroll, “New Archaic Coin Finds at Sardis,” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 109, 2005, pp. 589–617.

Dusinberre, E. R. M., Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2003.

Greenewalt, C. H., “When a Mighty Empire Was Destroyed: The Common Man at the Fall of Sardis, ca. 546 B. C.,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 136, 2003, pp. 247–271.

Greenewalt, Jr., C. H., “Sardis in the Age of Xenophon,” Pallas. Revue d’études antiques, No. 43, 1995, pp. 125–145.

Michels, C., “Cyrus’ II Campaigns Against the Medes and the Lydians,” in Herodot und das Persische Weltreich =: Herodotus and the Persian Empire: Akten des 3. Internationalen Kolloquiums zum Thema “Vorderasien im Spannungsfeld klassischer und altorientalischer Überlieferungen,” Innsbruck, 24.-28. November 2008 (Classica et Orientalia 3), edited by R. Rollinger, B. Truschnegg, and R. Bichler, Wiesbaden, 211, pp. 690–704.

Mierse, W. E., “The Persian Period,” in Sardis from Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, 1958-1975, ed. G. M. A. Hanfmann and W. E. Mierse, Cambridge, Mass. and London, 1983, pp. 100–108.

Ratté, C. J., “The Pyramid Tomb at Sardis,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen, vol. 42, 1992, pp. 135–161.

Stronach, D., “The Building Program of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and the Date of the Fall of Sardis,” in Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross-Cultural Encounters, edited by S. M. R. Darbandi and A. Zournatzi, Athens, 2008, pp. 149–173.