Sang-e Chakhmaqسنگ چخماق

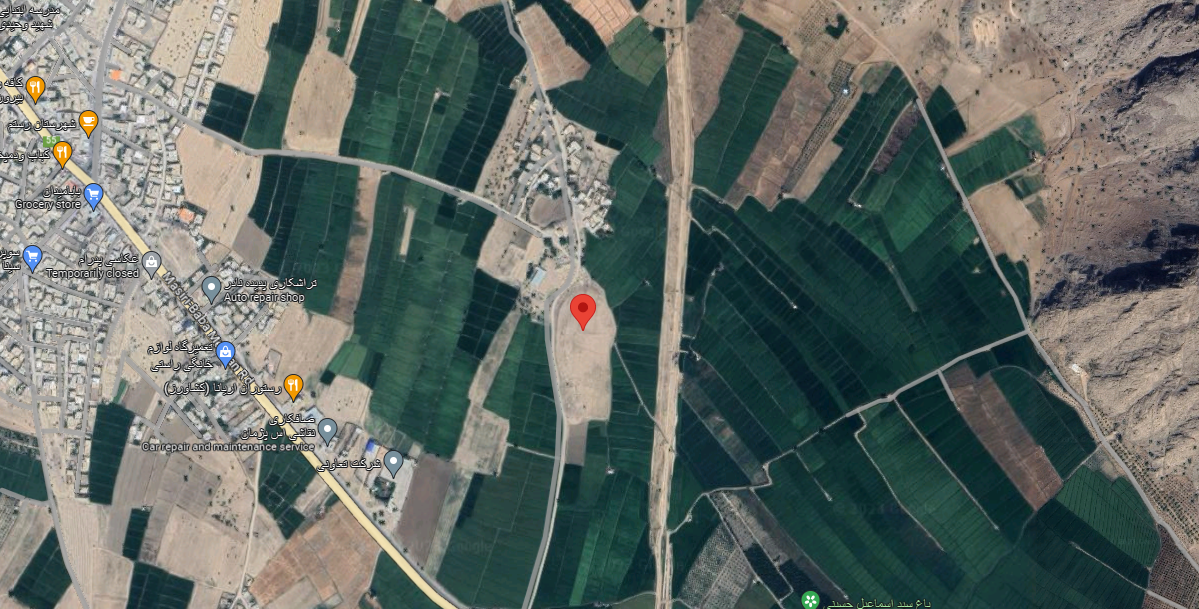

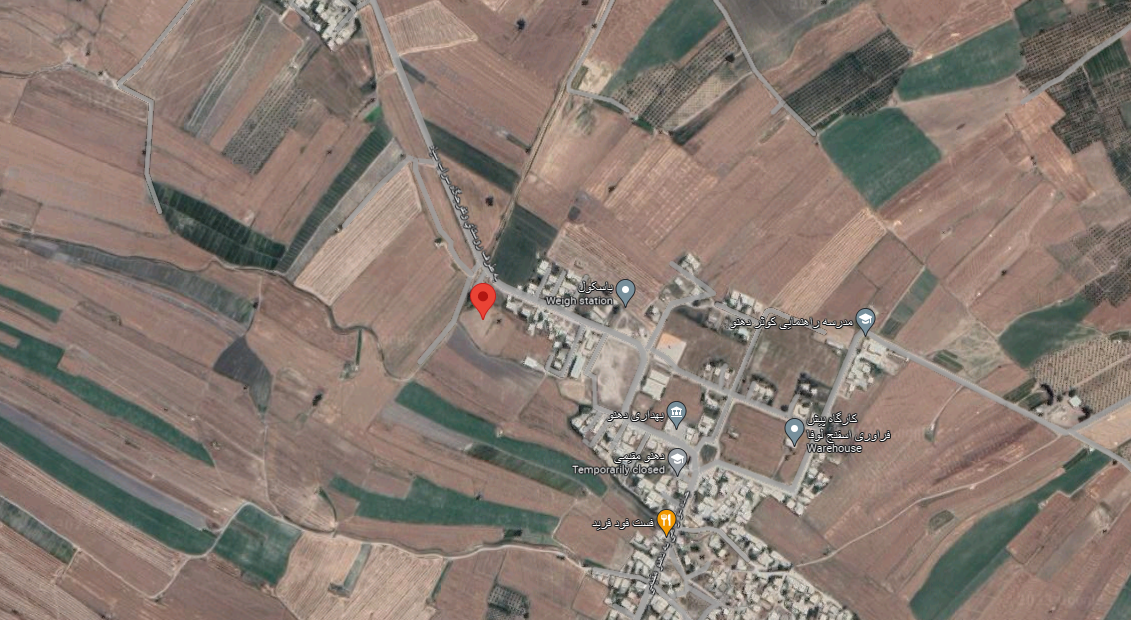

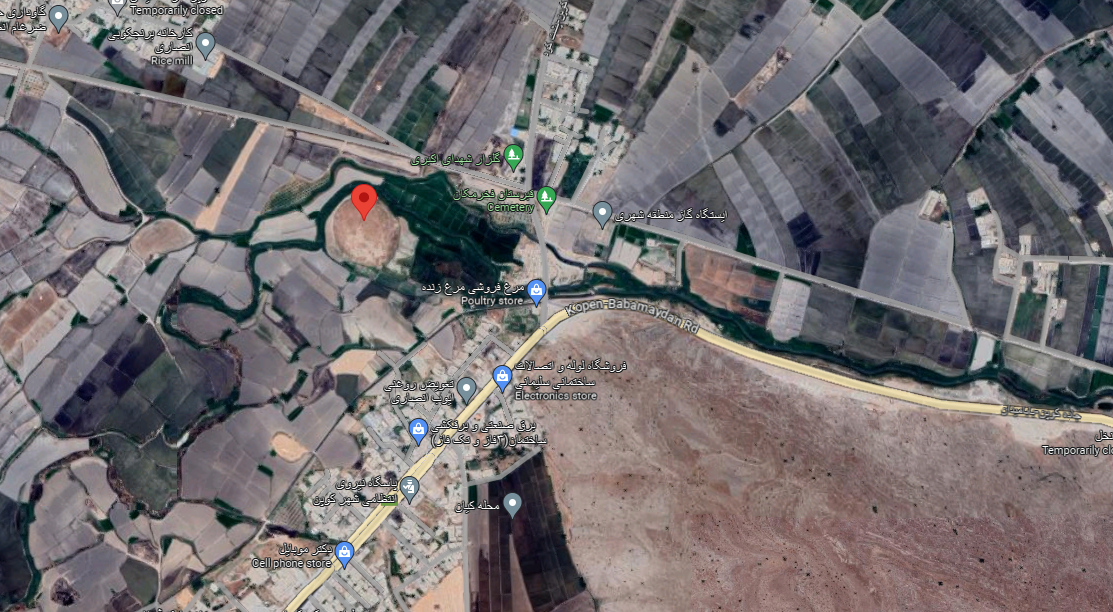

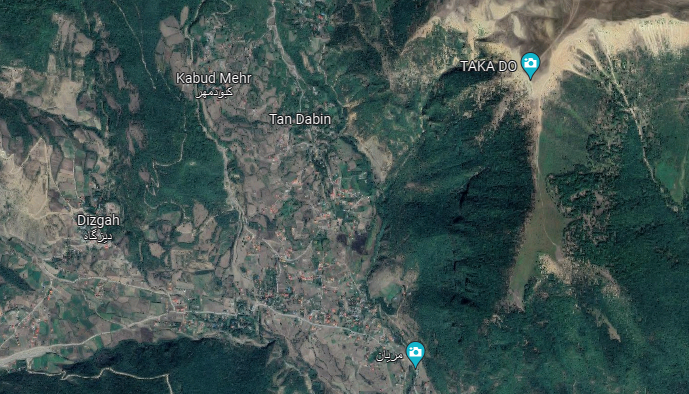

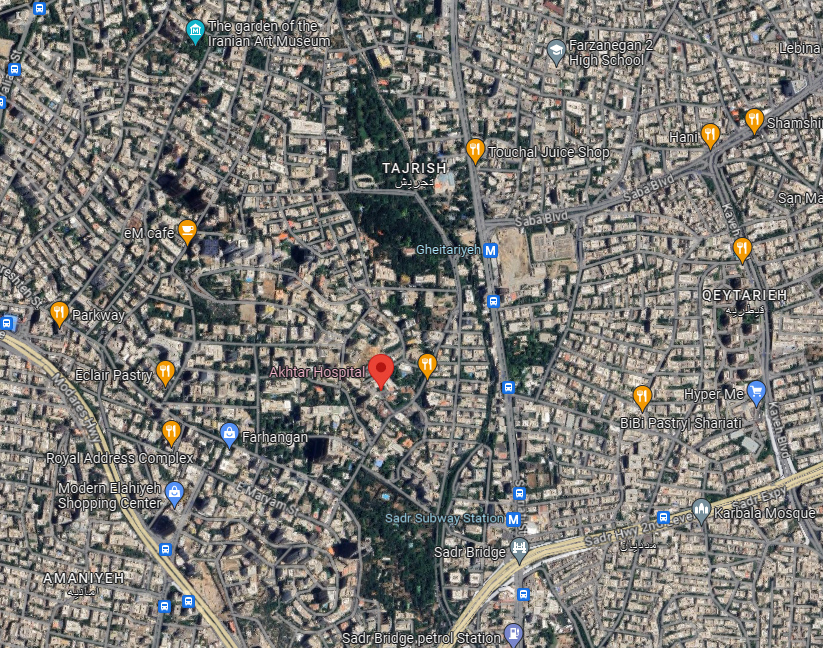

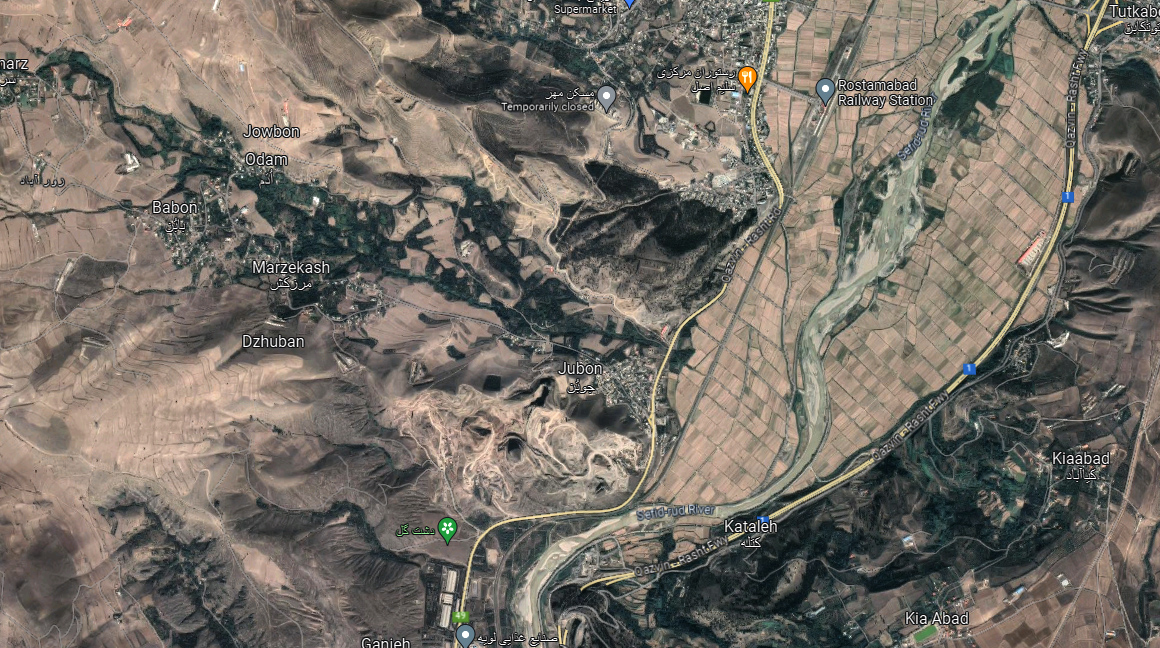

Location: Tepe Sang-e Chakhmaq is 7 km north of Shahrud, Semnan Province.

36°29’59.9″N 55°00’05.0″E

Map

Historical Period

Neolithic

History and description

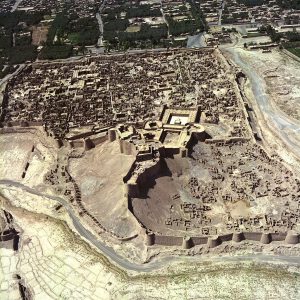

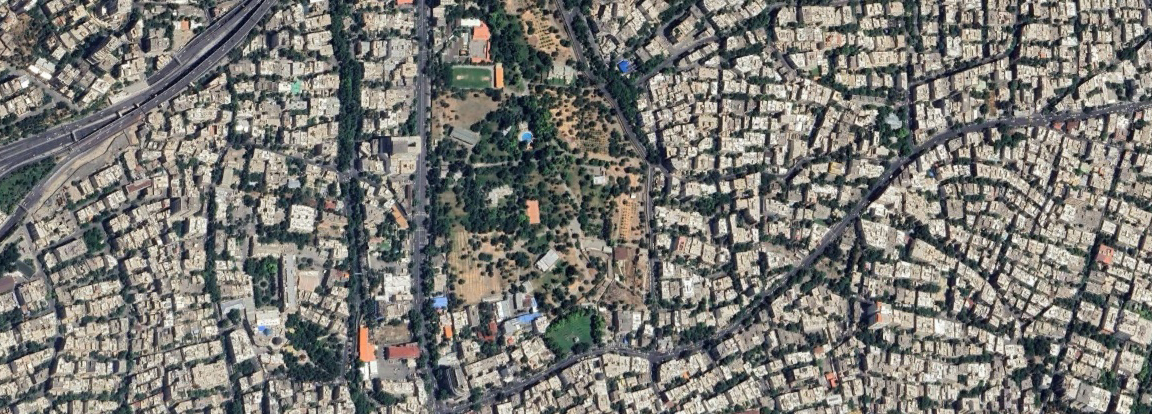

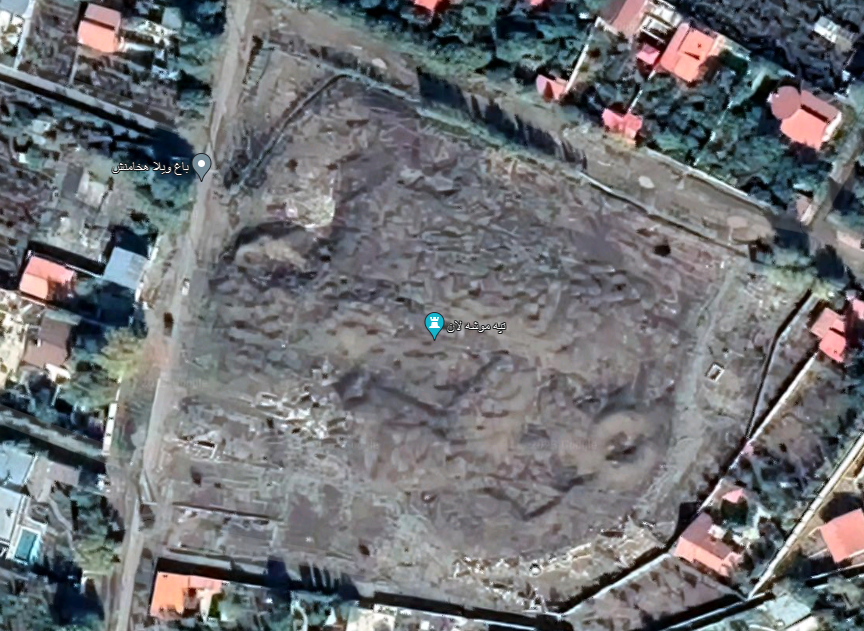

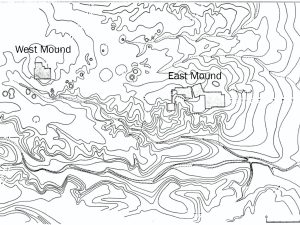

Tepe Sang-e Chakhmaq is located 7 km north of Shahroud and 1 km north of the historical town of Bastam in Semnan Province, northeast Iran. Tepe Sang-e Chakhmaq, literally meaning the Mound of Firestones, consists of two adjacent mounds, the West Mound and the East Mound, spaced approximately 100 meters apart (fig. 1). At an elevation of 1418 above sea level at the southern end of Bastam’s small plain, Sang-e Chakhmaq overlooks the Shāhvār peak (3945 m above sea level), which is the highest peak in the eastern Alborz Mountains. Like many other prehistoric sites in the Shāhrūd region, Sang-e Chakhmaq sits at the far end of an alluvial plain, adjacent to a dry drainage channel which, according to local knowledge, once had flowing water until a few decades ago.

The West Mound of Sang-e Chakhmaq, covering an area of 0.4 hectares and standing at a height of approximately 3 meters, is a pre/proto-ceramic Neolithic site dating to circa 7100-6700/6600 B.C. The excavation results revealed five levels for the site’s sequence based on architectural remains, labeled I-V from top to bottom (fig. 2). Houses were constructed from sun-dried mud bricks and pisé (a mixture of hard-packed clay and straw), some with finely plastered gypsum floors. The plaster-floored rooms were typically divided into three sections distinguished by varying floor levels and featured raised hearths and mud-brick platforms. A handful of sherds, (four pieces from the Japanese excavations and two pieces from the 2009 sounding) attest to the incipient stage of pottery making at the site, making it one of the few sites on the Iranian Plateau with such evidence. Therefore, the West Mound might be considered a Proto-Ceramic Neolithic site.

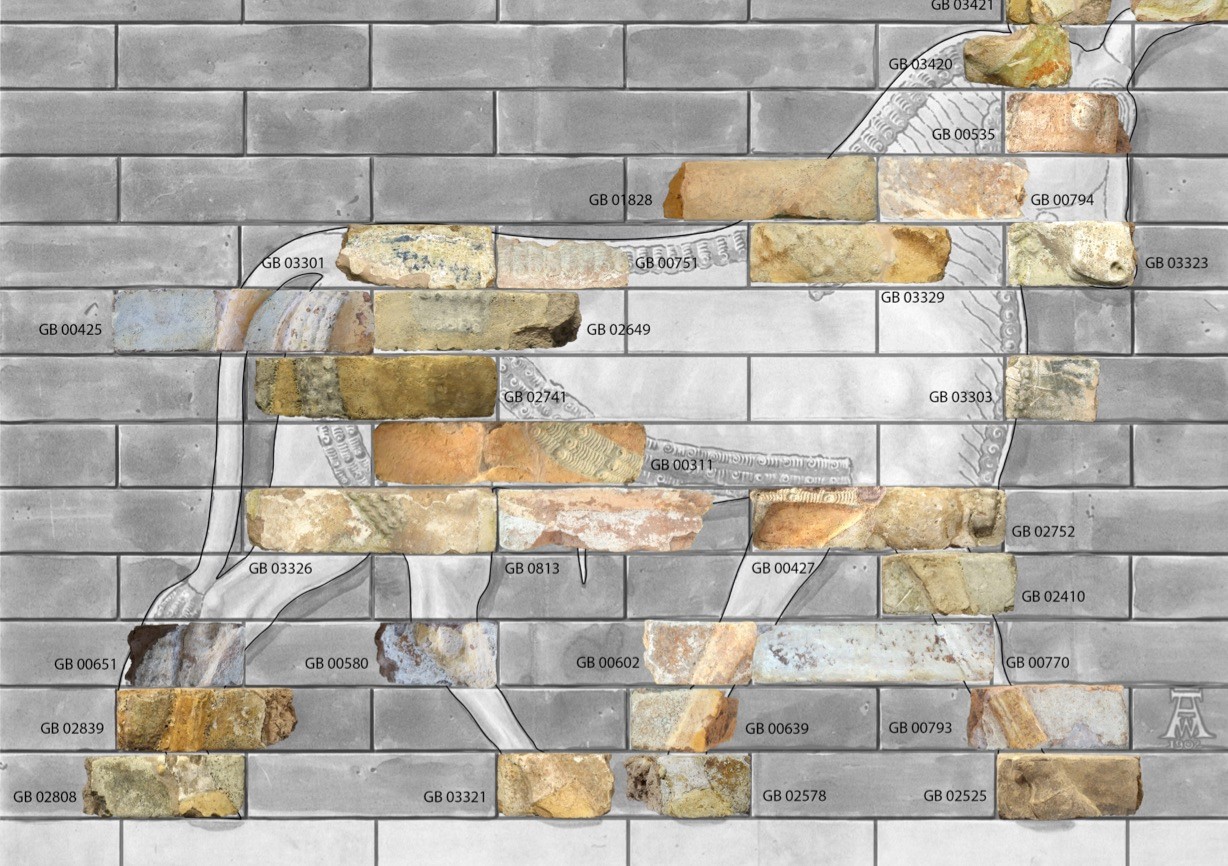

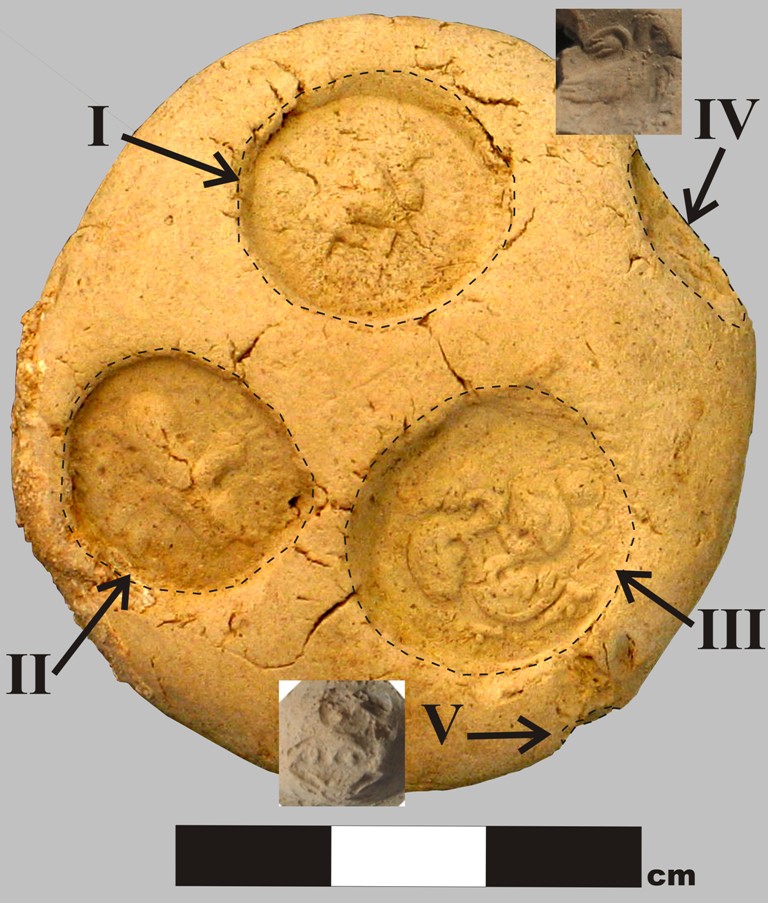

The lithic industry of the West Mound is primarily characterized by roughly shaped bladelets and blades, with a limited presence of backed bladelets, drills, geometric tools, end scrapers, and cores. Light brown chert, gray flint, and chalcedony were the preferred materials, although a few artifacts made of obsidian were also recovered. Obsidian, an exotic raw material, was utilized from the earliest phase of occupation and remained in use throughout the site's sequence. Analyses indicate that the obsidian from the West Mound was sourced from the Bingöl B and Bingöl A volcanic regions in eastern Anatolia. Additionally, a substantial number of clay figurines, primarily depicting animals and humans, were recovered from the ash-rich deposits of the West Mound (fig. 3).

Bioarchaeological studies of plant and animal remains from the West Mound suggest that the inhabitants consumed a wide range of domesticated species (including wheat, barley, and goats) and wild species (especially gazelles). Thus far, the WM of Sang-e Chakhmaq and the site of Rouyan located approximately 13 kilometers farther south represent the earliest Neolithic occupations in northeastern Iran. The presence of domesticated species, sophisticated architecture, and Anatolian obsidian at the West Mound all indicate that the Neolithic way of life was introduced into the northeastern Iranian Plateau around the turn of the 8th millennium B.C.

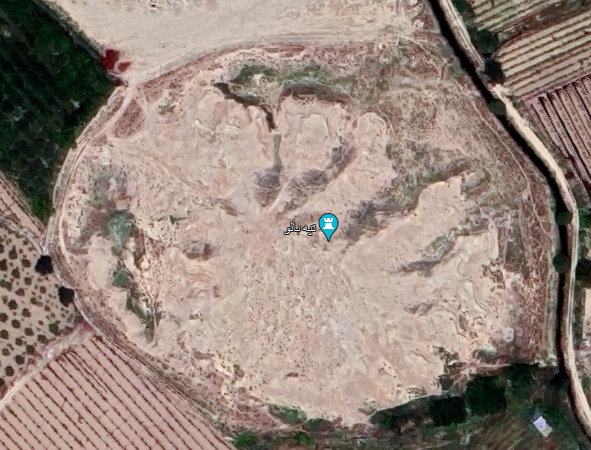

The East Mound of Sang-e Chakhmaq is an oval-shaped mound approximately 4 meters high, containing over 5 meters of archaeological deposits (fig. 4). Based on the excavations by a Japanese team, the archaeological sequence is divided into six levels, labeled I to VI, from top to bottom, based on architectural remains (fig. 5). The architecture of the East Mound exhibits noticeable differences from that of the West Mound. Instead of the tripartite buildings with gypsum floors characteristic of West Mound architecture, the East Mound revealed remains of multi-room buildings with somewhat irregular plans.

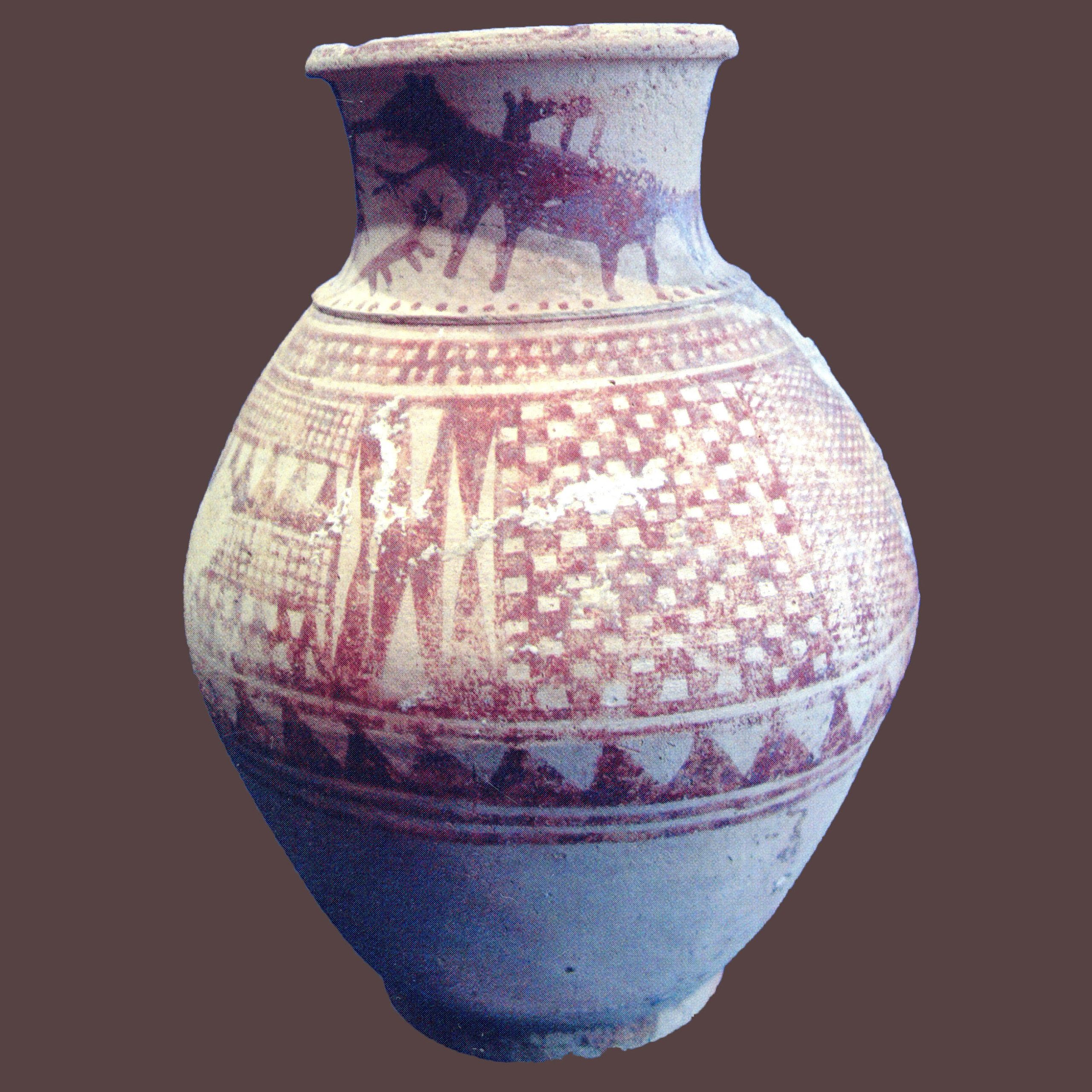

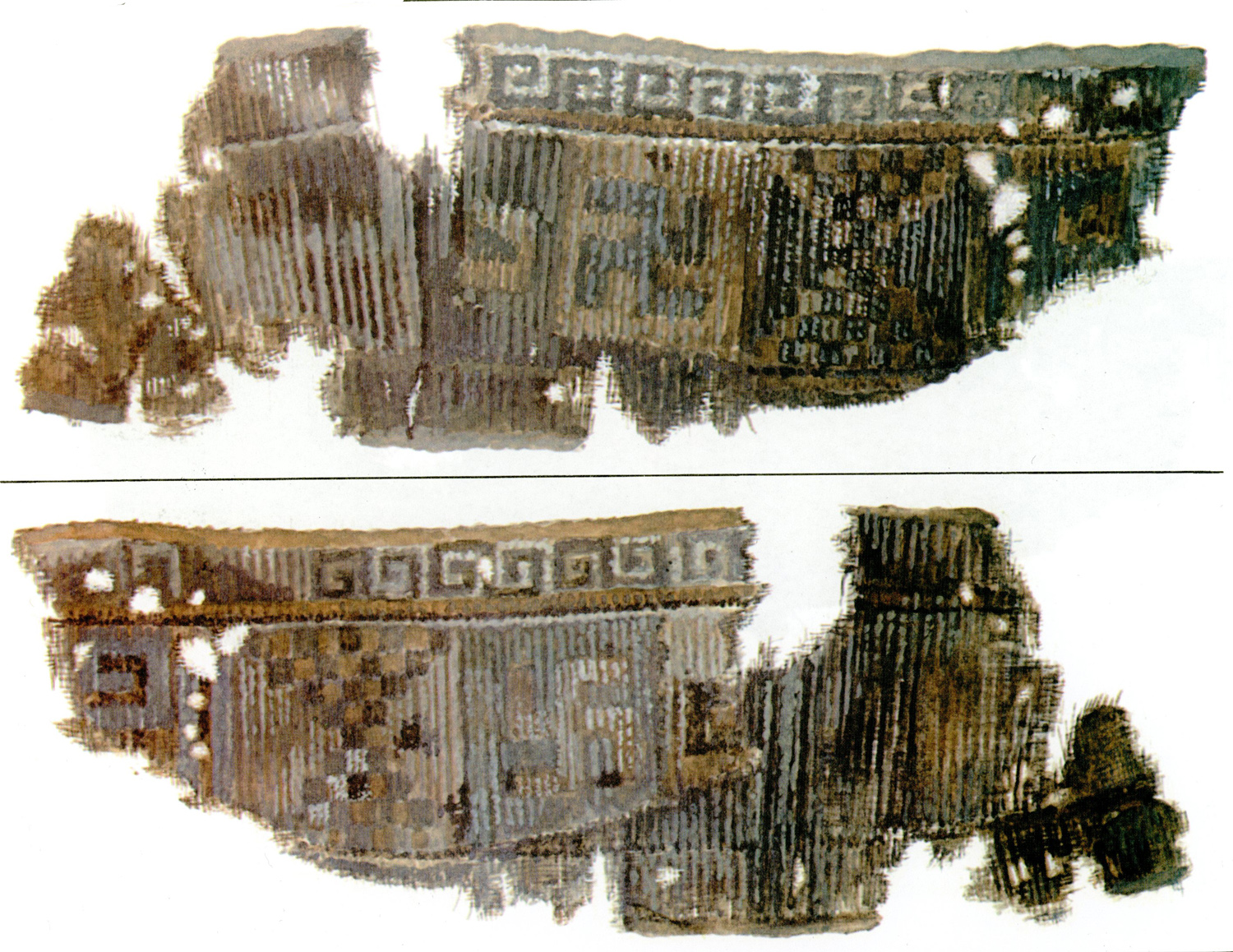

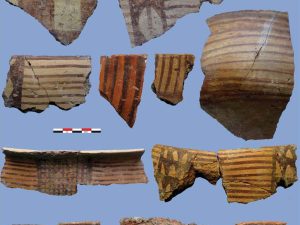

From the earliest level, the East Mound produced a wealth of ceramic corpus (fig. 6). The ceramic of the East Mound is handmade, almost exclusively tempered with chopped straw or other plant materials. The ceramics of the East Mound are essentially painted, showing various linear and geometric designs. Wavy lines were predominant in the lower levels. Other common motifs include chequerboards, triangles, and lozenges rendered in multiple combinations. The favored colors for painting were brown, reddish-brown, or, red, with rare examples of black, applied on usually a tan surface.

By introducing and utilizing a greater variety of plant and animal species, such as free-threshing wheat, sheep, and cattle, the subsistence economy of the East Mound inhabitants was more diverse than that of the West Mound. This economy was further supplemented by the hunting of wild species, particularly gazelles and onagers.

According to the available radiocarbon dates, the occupation of the East Mound (approximately 6300/6200-5300 B.C.) commenced nearly half a millennium after the occupation of the West Mound came to an end. Evidence of this occupational gap has recently been well documented at the site of Rouyan, on the southern outskirts of the city of Shahroud, which shows a continuous occupation from around 7000 B.C. to probably after 5000 B.C.

Fig. 1. The topographic plan of Sang-e Chakhmaq with the two mounds (image: Masuda, “Excavation at Tappeh Sang-e Caxmaq,” Archiv für Orientforschung, fig. 1).

Fig. 2. . The north and west walls of the stratigraphic trench at the West Mound.

Fig. 3. A selection of clay figurines from the West Mound.

Fig. 4. The stratigraphic trench at the East Mound.

Fig. 5. The stratigraphic trench at the East Mound.

Fig. 6. A selection of typical Chakhmaq Neolithic ceramics from the East Mound.

Archaeological Exploration

Sang-e Chakhmaq was discovered by the Japanese archaeologist, Seiichi Masuda, in 1969, and was excavated over four seasons between 1971 and 1977. Despite being one of the largest Neolithic site excavations in Iran, covering approximately 1800 square meters, Masuda's work at Sang-e Chakhmaq largely remained unpublished. The site was reinvestigated by Kourosh Roustaei on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, in 2009 .

Finds

Excavated finds consist of typical Neolithic sherds of northeastern Iran, human and animal figurines in clay; blades in obsidian.

Bibliography

Fuller, D., “Charred remains from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq, and a Consideration of Early Wheat Diversity on the Eastern Margins of the Fertile Crescent,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 33-36.

Furusato, S., “Figurines of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by A. Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 23-26.

Hisada, K., “Geologic Setting of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10 - 11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 1-4.

Kurosawa, M., “Mineralogical study of pottery from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 19-22.

Mashkour, M. et al., “Neolithisation of Eastern Iran: New Insights Through the Study of the Faunal Remains of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 27-32.

Masuda, S., “Excavations at Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in Proceedings of the First Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran 1972, edited by Firouz Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1972, 2 pages and 11 figures (published in fascicules).

Masuda, S., “Excavations at Tappeh Sang-e Čaxmāq,” in Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Symposium of Archaeological Research in Iran, 1973, edited by Firouz Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1974, pp. 23-33.

Masuda, S., “Report of the Archaeological Investigations at Šahrud, 1975, in Proceedings of the 4th Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran 1975, edited by Firouz Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1976, pp. 63-70.

Masuda, S., Tappeh Sang-i Chaxmaq, Tokyo, 1977 (in Japanese).

Masuda, S., “Excavation at Tappeh Sang-e Caxmaq,” Archiv für Orientforschung, vol. XXXI, 1984, pp. 209-212.

Masuda, S., T. Gotō, T. Iwasaki, H. Kamuro, S. Furusato, J. Ikeda, A. Tagaya, M. Minami, and A. Tsuneki, “Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq: Investigations of a Neolithic Site in Northeastern Iran,” in The Neolithisation of Iran: The Formation of New Societies, edited by Roger Matthews and Hasan Fazeli Nashli, Oxford and Oakville, 2013, pp. 201-240.

Miyauchi, Y., “Children at Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 43-46.

Nakamura, T., “Radiocarbon Dating of Charcoal Remains Excavated from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 9-12.

Pichon, F. et al., “Harvesting Cereals at Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and the Introduction of Farming in Northeastern Iran during the Neolithic,” Plos One, vol. 18(8): e0290537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0290537

Roustaei, K., “Stratigraphic Soundings at Sang-e Chakhmaq Tappehs, Shahroud, Iran; April- June 2009,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 47-49.

Roustaei, K., M. Mashkour and M. Tengberg, “Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and the beginning of the Neolithic in north-east Iran,” Antiquity, vol. 89 (345), 2015, pp. 573-595.

Roustaei, K., “An Emerging Picture of the Neolithic of Northeast Iran,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 51, 2016, pp. 21-55.

Roustaei, K. and B. Gratuze, “Eastward Expansion of the Neolithic from the Zagros: Obsidian Provenience from Sang-e Chakhmaq, a Late 8th-Early 7th Millennia BCE Neolithic Site in Northeast Iran,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, vol. 29, 2020, pp. 1-10.

Roustaei, K. and H. Rezvani, “New Evidence of Two Transitions in the Neolithic Sequence of Northeastern Iran”, Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 84/4, 2021, pp. 252-261.

Tagaya, A., “Human remains from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 39-42.

Tangberg, M., “First Archaeobotanical Results from the 2009 Soundings at Sang-e Chakhmaq East and West Mounds,” ,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 51-53.

Tano, K., “Vegetation of the Chakhmaq site based on charcoal identification,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 37-38.

Thornton, Ch. P., “Sang-e Chakhmaq,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, Brill, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_10684

Tsuneki, A., “The Site of Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 5-8.

Tsuneki, A., “Pottery and Other Objects from Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq,” in The First Farming Village in Northeast Iran and Turan: Tappeh Sang-e Chakhmaq and Beyond, University of Tsukuba, February 10-11, 2014, Program and Abstracts, edited by Akira Tsuneki, Tsukuba, 2014, pp. 13-18.