Sāleh Dāvoodصالح داوود

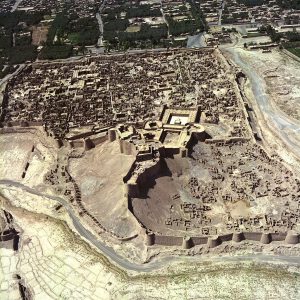

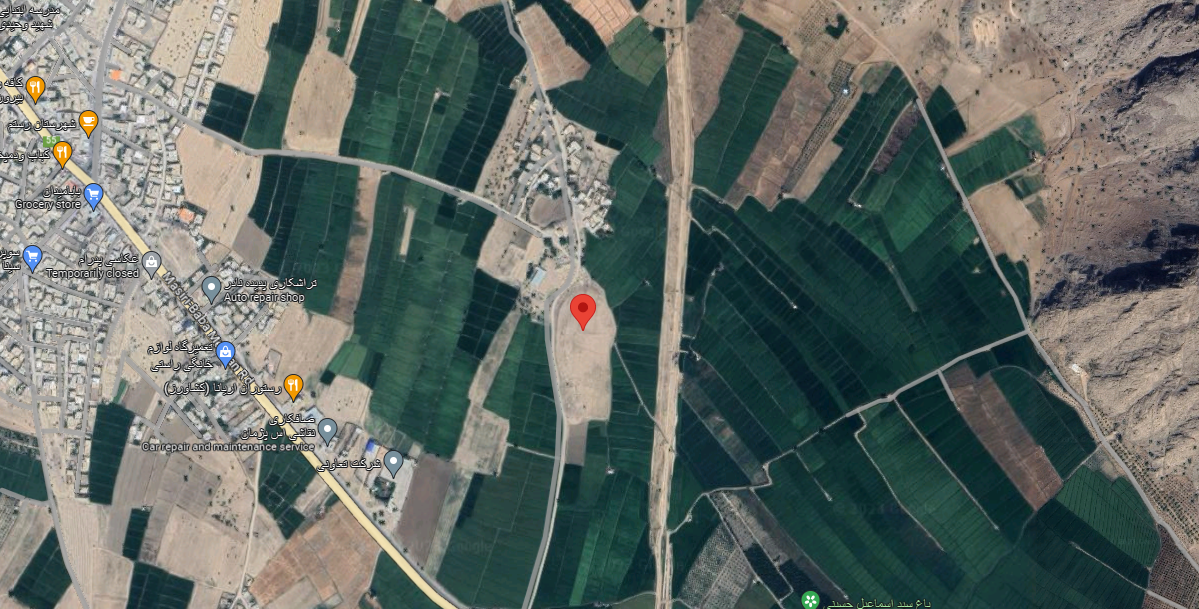

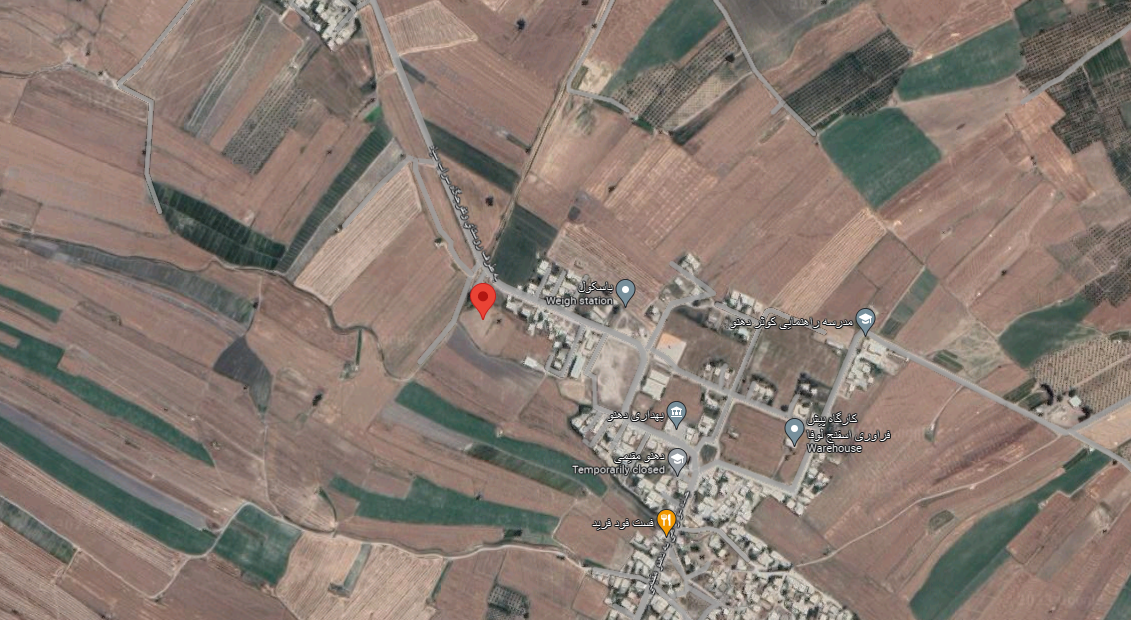

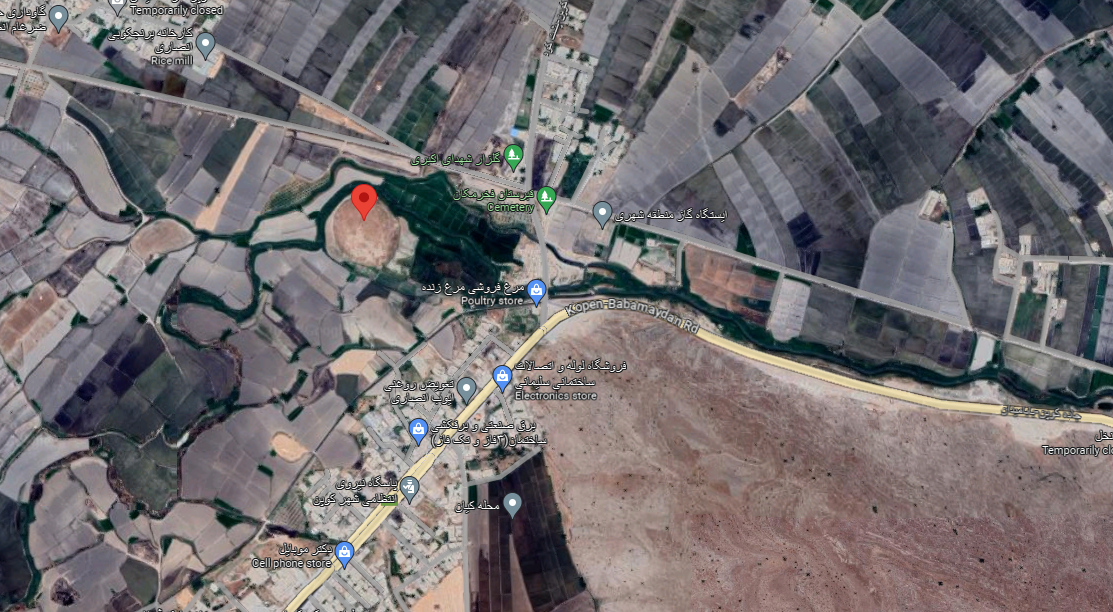

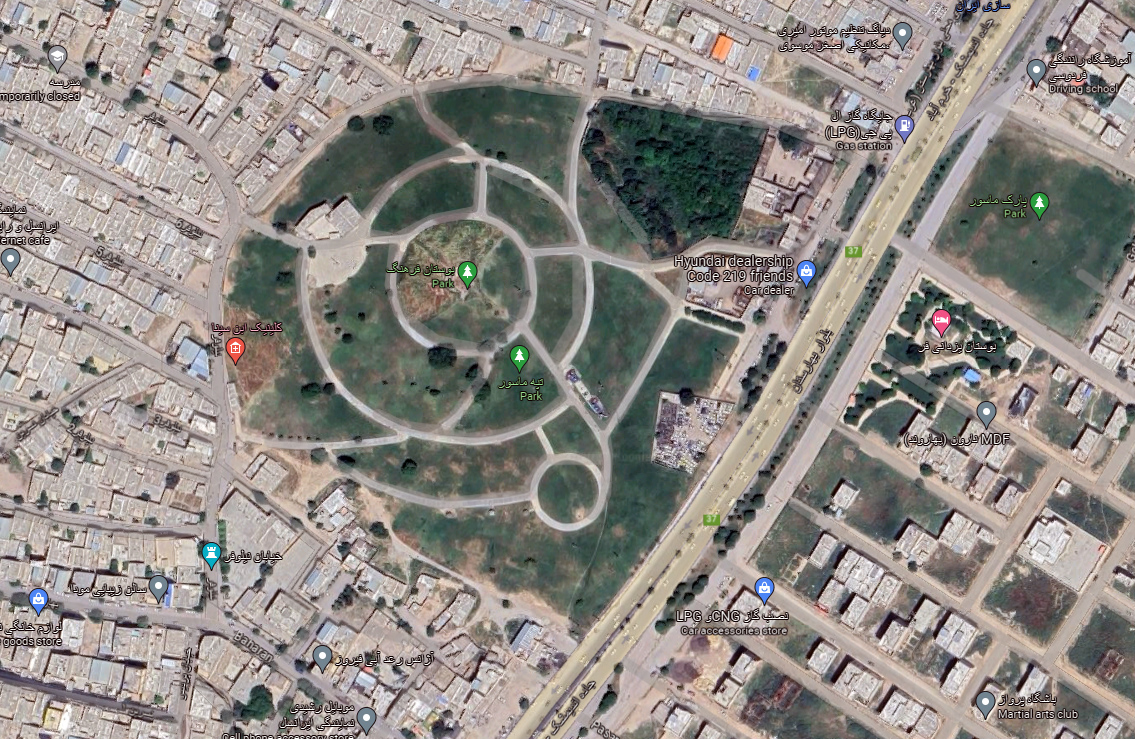

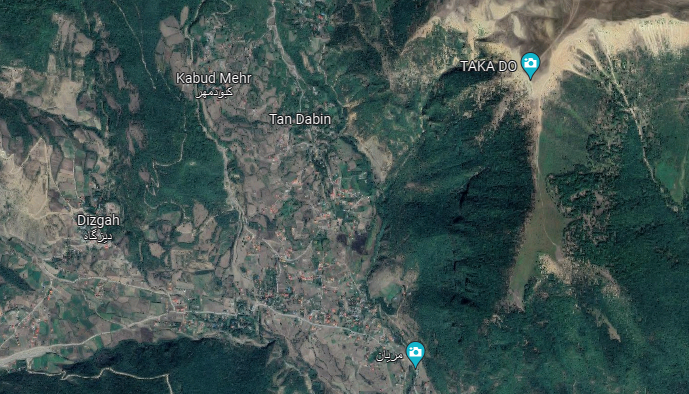

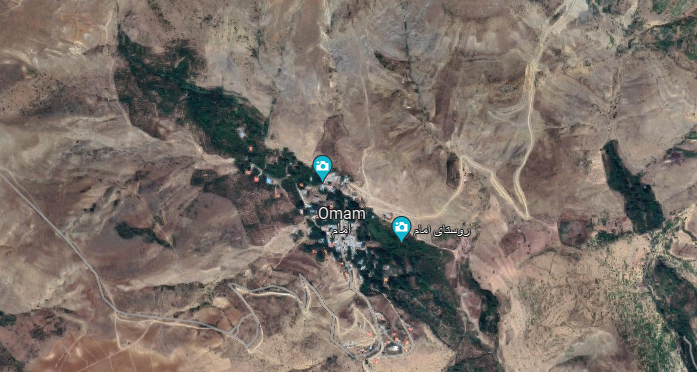

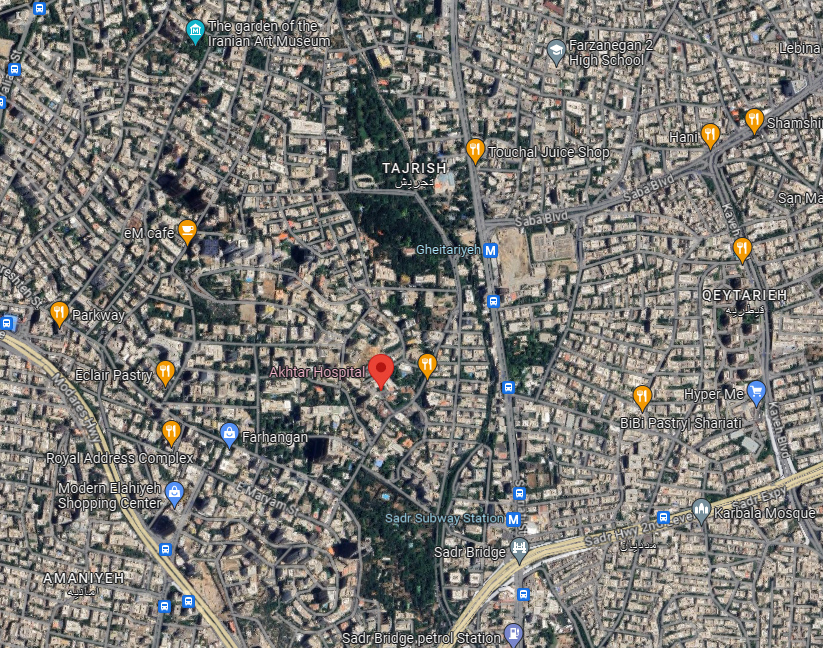

Location: Sāleh Dāvood is located 25 km southwest of Dezful, in southwestern Iran, Khuzestan Province.

32°21’7.89″N 48° 8’29.20″E

Location:

Historical Period:

Parthian / Elymaean (150 B.C. – 224 A.D.)

History and Description:

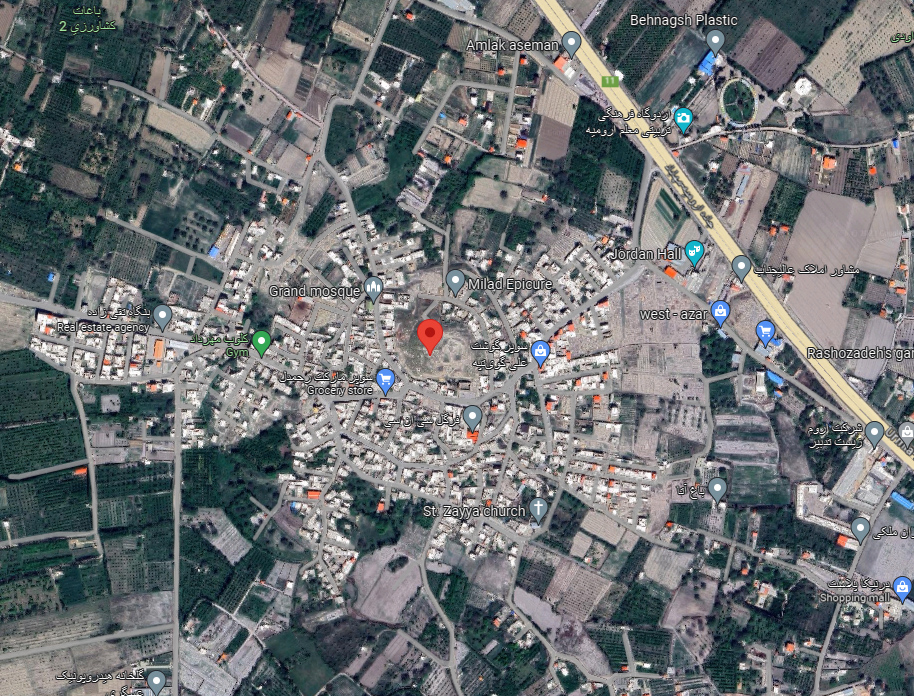

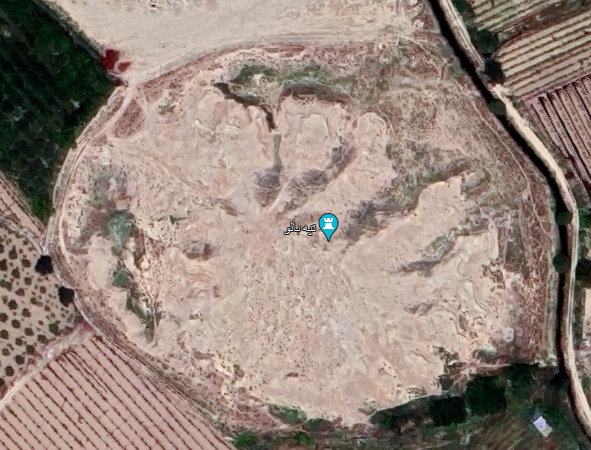

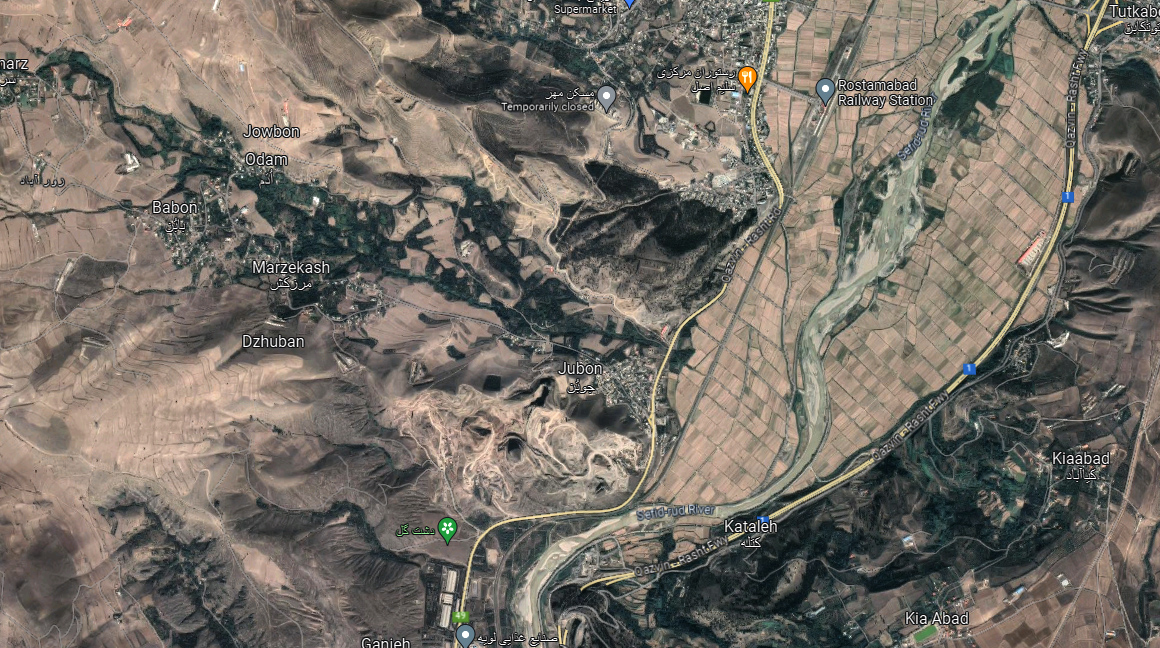

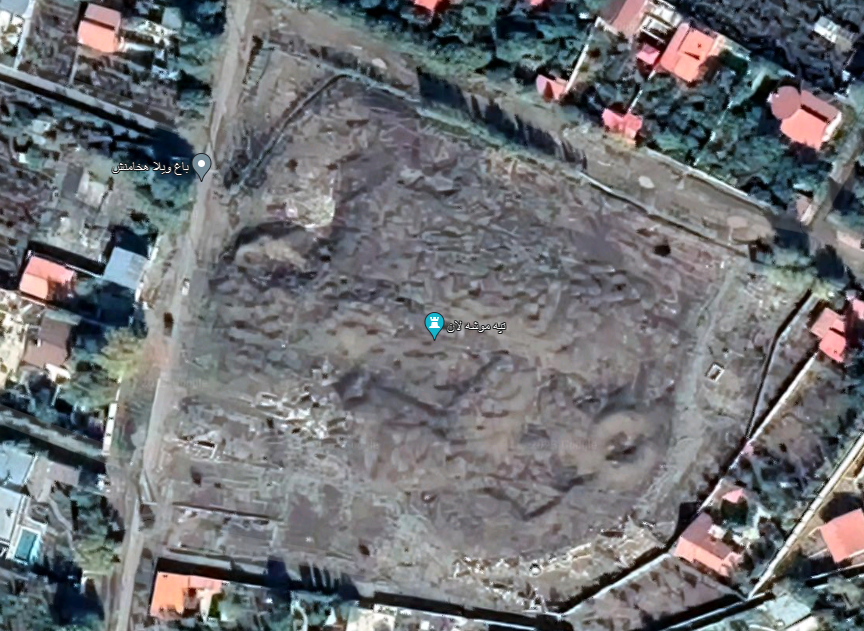

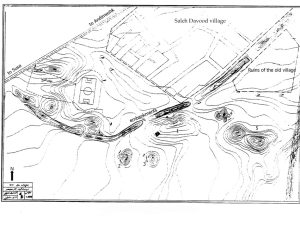

The village of Sāleh Dāvood lies on the west bank of the Karkheh River, 1.5 km northeast of the Sasanian site of Eyvān-e Karkheh, and 25 km southwest of Dezful. On the eastern edge of the village, there is a flat top mound (200 x 110 x 4 m), which has been used as the cemetery of the present-day village. It seems that the archaeological site consisted of a series of low but extended mounds (fig. 1). Iraqi forces occupied the small village of Sāleh Dāvood in 1980, during the Iran-Iraq war, and they cut trenches and built an embankment 10 m wide and 4 m high. Typical Parthian-Elymaean potsherds, fragments of bricks, and large jars are still visible at Sāleh Dāvood.

Fig. 1. Topographic map of Sāleh Dāvood (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 294, fig. 4).

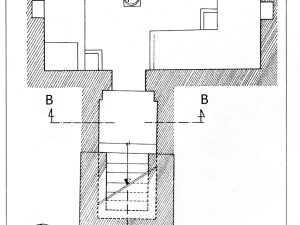

Fig. 2. Tomb 1 (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 300, fig. 6).

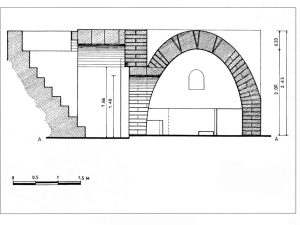

Fig. 3. Section of the underground tomb showing the stairway and the vaulted chamber (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 301, fig. 7)

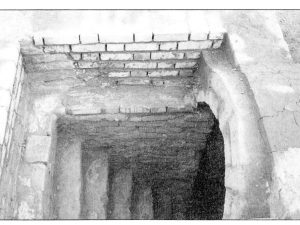

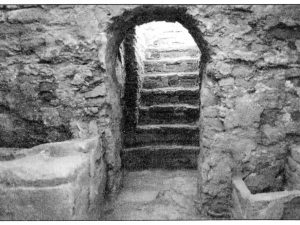

Fig. 4. Entrance to the tomb with the stairway leading down to the vaulted tomb chamber. Note that the upper courses of bricks have been restored (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 297, pl. 10).

Fig. 5. Part of the vaulted stairway (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 300, pl. 15)

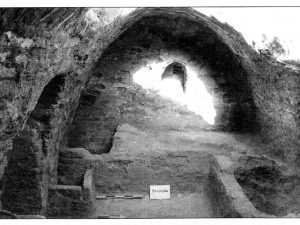

Fig. 6. Entrance and its vaulted hallway as seen from the tomb chamber (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 297, pl. 11)

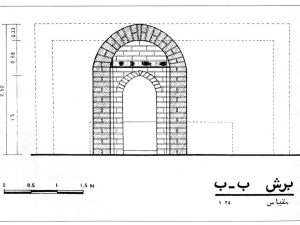

Fig. 7. Section of the vaulted doorway (after Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 301, fig. 8)

Fig. 8. The subterranean tomb with its parabolic vault. The receptacles were broken by clandestine diggers (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 298, pl. 12).

Fig. 9. The tomb chamber with mud-brick beds and receptacles (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 298, pl. 13)

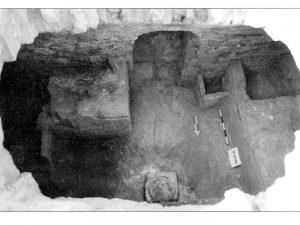

Fig. 10. View of the tomb chamber from above (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 299, pl. 14)

Fig. 11. One of the jar burials found at Saleh Davood (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 295, pl. 8)

Archaeological Exploration:

Mehdi Rahbar conducted rescue excavations at Sāleh Dāvood on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research in the winter of 2009.

Soundings and stratigraphy: Rahbar opened two soundings, one at the eastern extremity of the main mound, the other on the western edge of it. The opening of the first sounding was to determine the stratigraphy of the site; the trench reached the sterile soil at a depth of 4.10 m. Ceramic finds from the stratigraphic sounding show that the mound was exclusively occupied in the Parthian period, most probably in the first century A.D. The second sounding yielded remains of a structure (platform?) in burnt brick, approximately 3 x 2 m.

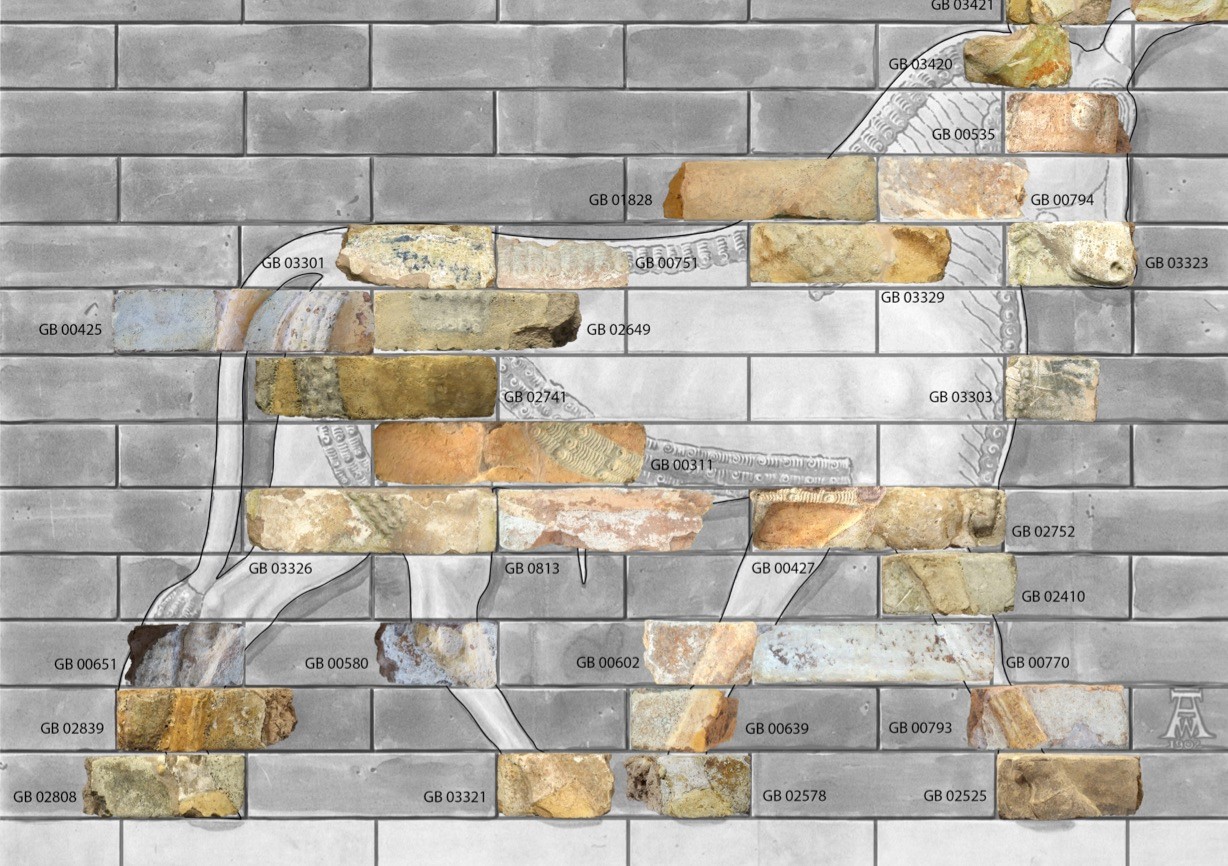

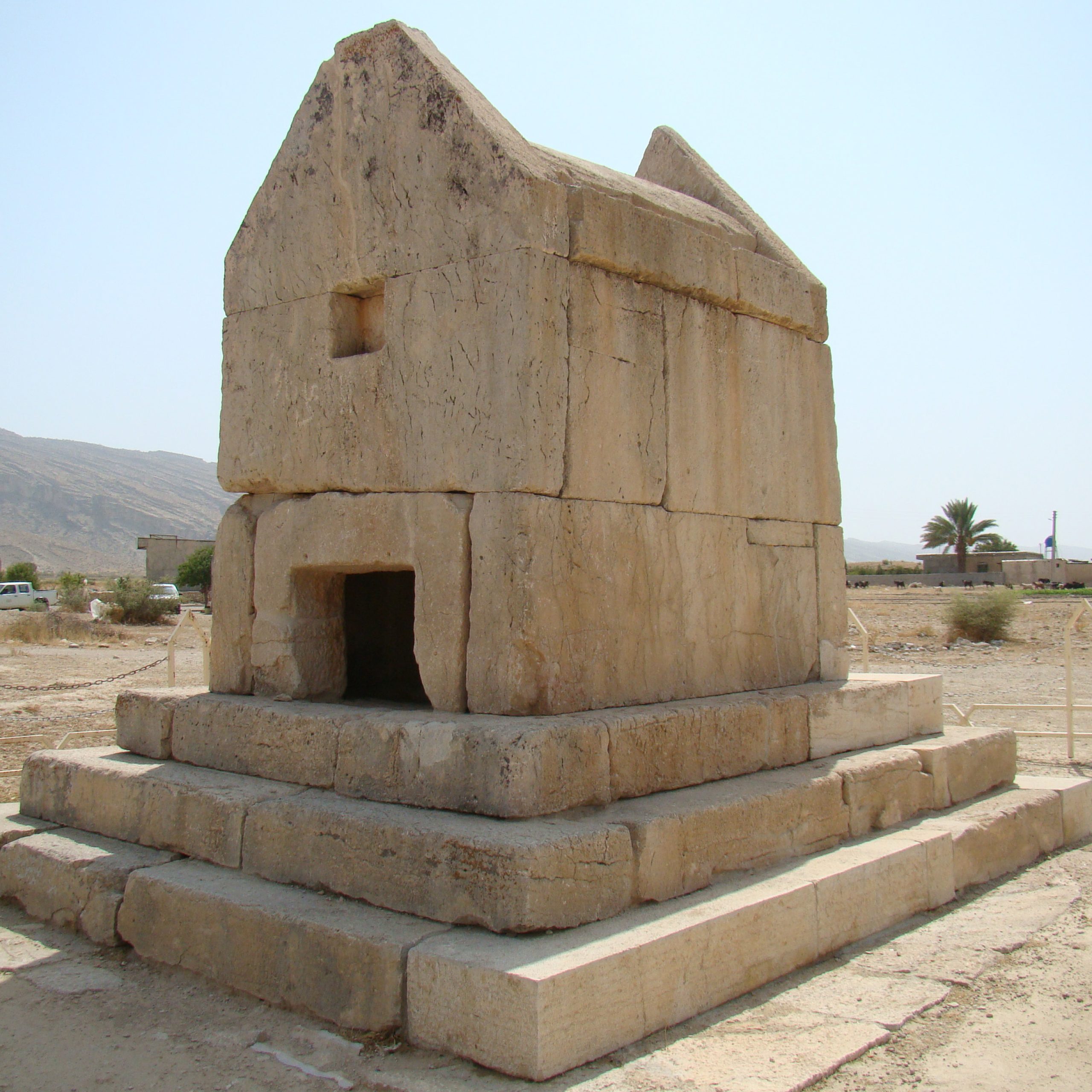

Underground tomb: A large underground, vaulted tomb (4.20 x 2.30 m) was uncovered in the excavation of the main mound. The tomb is made of two areas: a staircase and the tomb chamber (figs. 2, 3). The tomb is in burnt brick with mortar used as binding. The actual entrance and the vaulted hallway were carefully sealed with stone slabs (fig. 4). Nine steps leading to a short, vaulted hallway of more than 2 m long contrived access (figs. 5, 6, 7). A total of ten burials and grave goods were inside the tomb. A semi-parabolic vault 2.20 m high covers the main hall equipped with mud-brick platforms or beds (fig. 8). Due to the humidity in the soil, the skeletal remains were not preserved. Besides, five mud-brick receptacles (which Rahbar calls ossuaries) were identified inside the tomb (figs. 9, 10). According to the excavator, the ten identified burials were all secondary internments. The majority of skeletons were either disintegrated due to the soil humidity or disturbed and broken because of clandestine excavations.

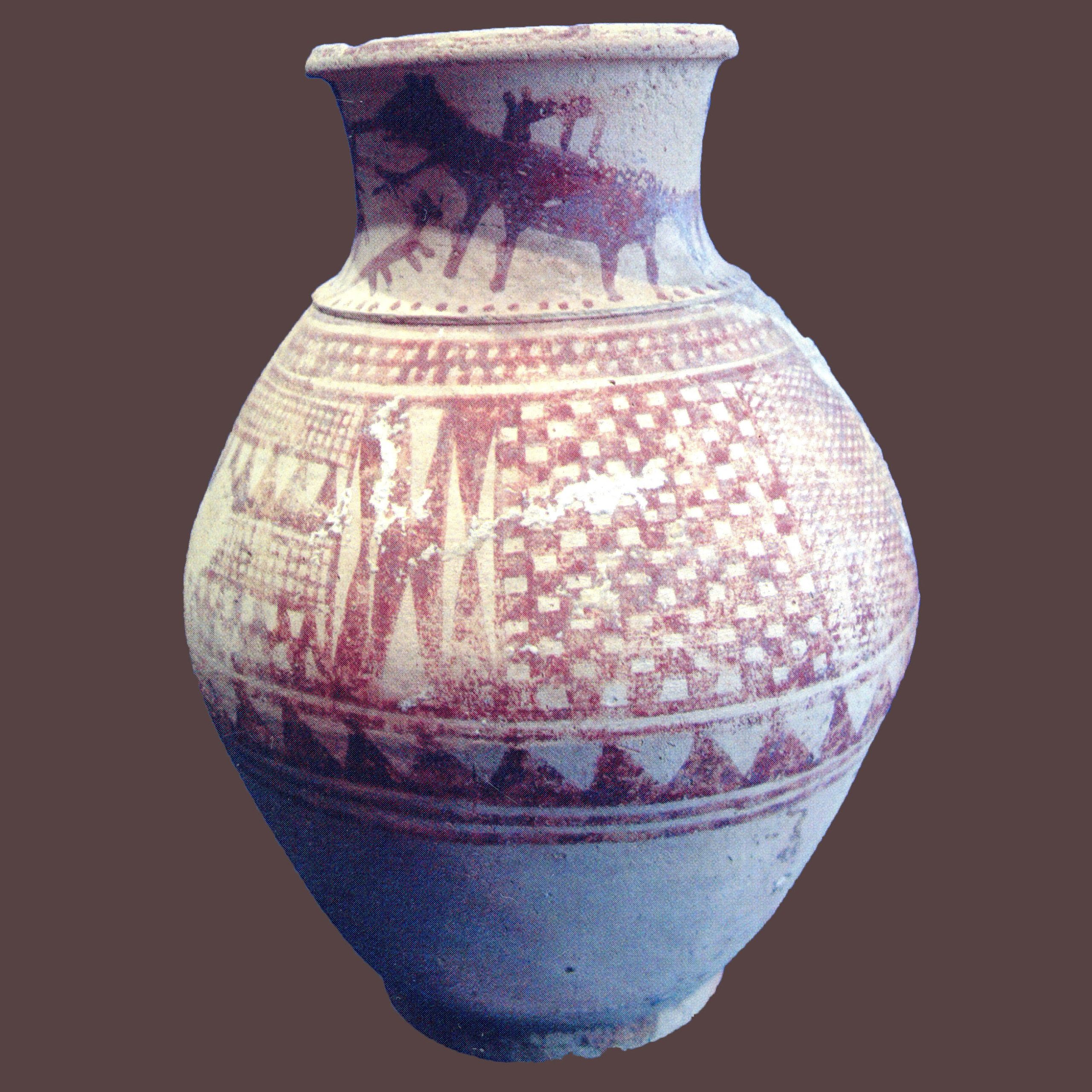

Jar burials: Two tall jars containing human skeletal remains were uncovered within a mud-brick structure (fig. 11). The first jar (jar 108), 132 x 40 cm, enclosed the skeleton of a 15-year-old boy; grave goods consist of a copper ring, the oxidized iron blade of a knife, and a ceramic tripod. The second burial (jar 109) was made of two jars put together to meet the length of the dead (195 cm).

Finds:

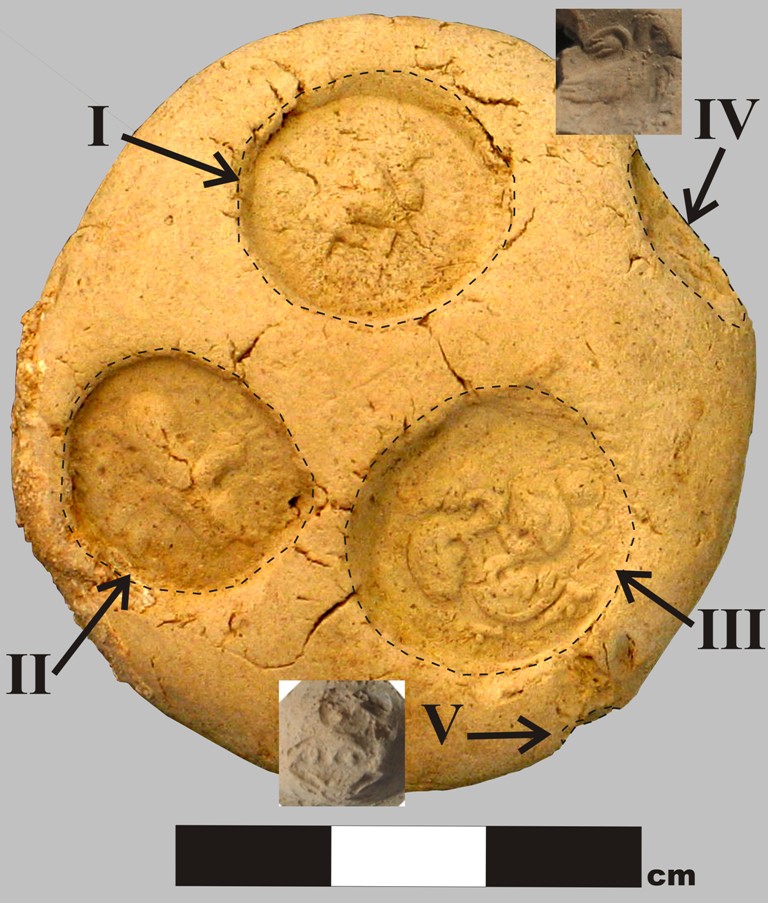

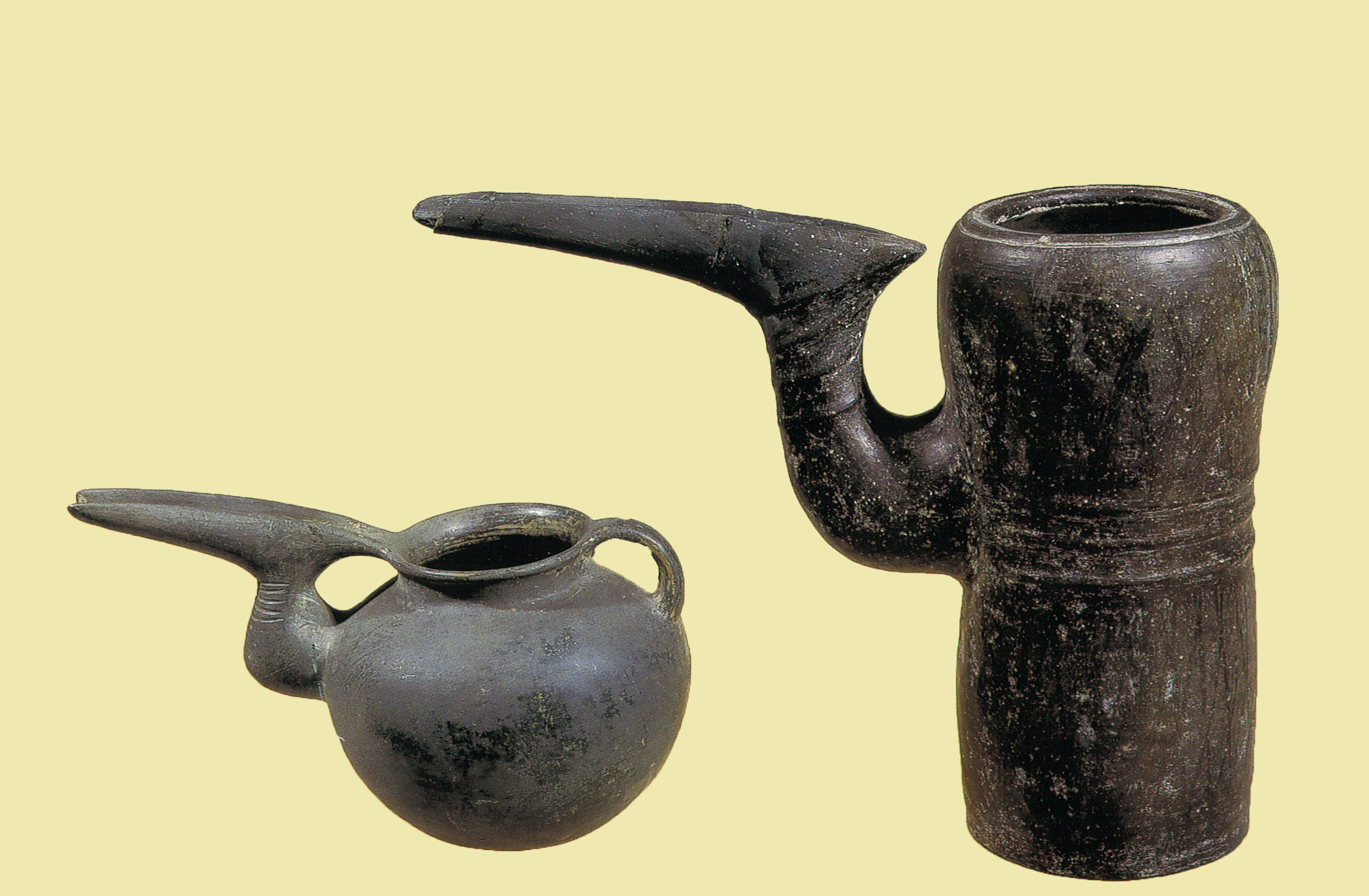

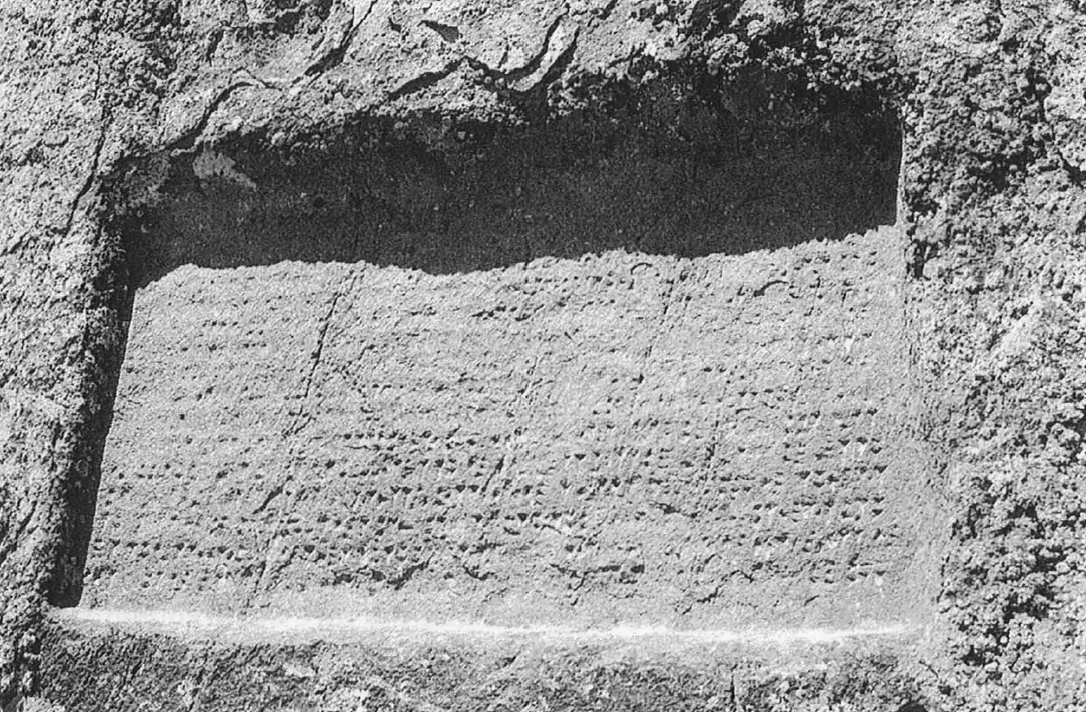

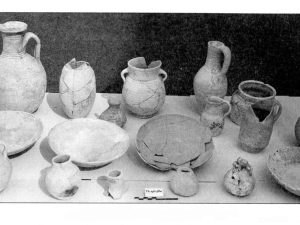

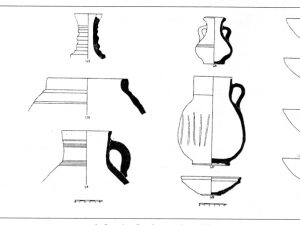

Stone seals and gems with intaglios were retrieved bearing Hellenized figures, including one that depicts a naked man holding a staff and a bag; the excavator identified the figure as that of Hermes, the messenger deity and a guide of travelers. The tomb contained a large number of stone beads forming bracelets; grinding stones, and copper coins (fig. 12) with the effigy of a king; the coins date from the reign of Orodes I (80-90 BC) to the reign of Orodes III (4-5 A.D.). Ceramic finds (fig. 13, fig. 14) are abundant in the tomb: typical Parthian glazed ceramics, Clinky Ware, lumps, and fragmentary figurines in terracotta. Some of the potsherds bear impressions depicting birds and geometric motifs.

12. Coins found in the tomb chamber (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 308, pl. 24)

13. Ceramic vessels found in the tomb chamber (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 310, pl. 28)

14. Drawing of ceramic finds from Saleh Davood (Rahbar, “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” p. 310, fig. 11)

Bibliography

Rahbar, M., “Ārāmgāh-e zirzamini-ye elymā’i dar Sāleh Dāvood,” Nāmvarnāmeh. Papers in Honour of Massoud Azarnoush, H. Fahimi and K. Alizadeh (eds.), Tehran, 1391 H.S./2012, pp. 289-314.