Robāt Māhiرباط ماهی

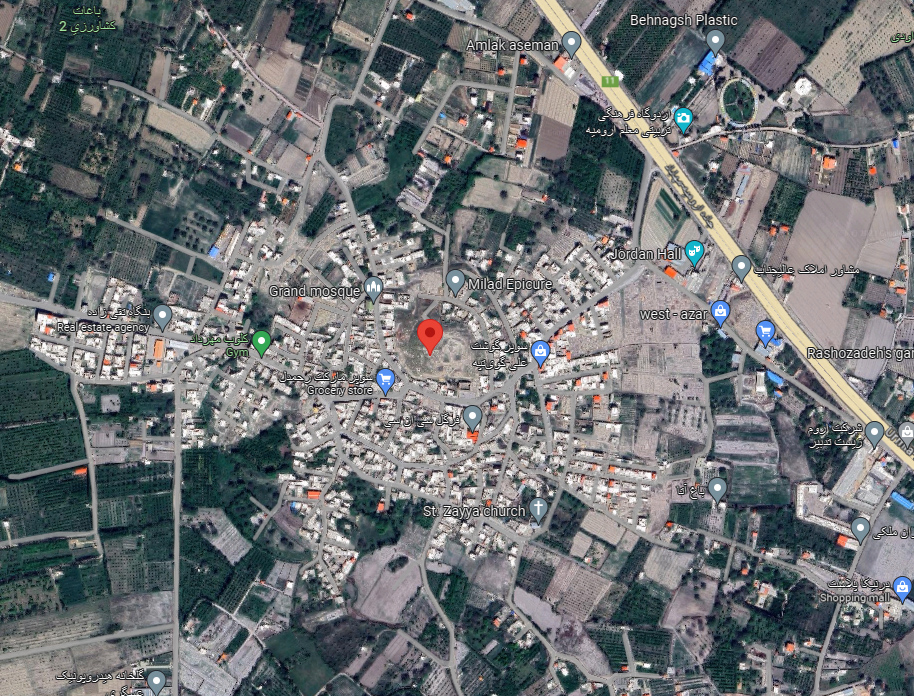

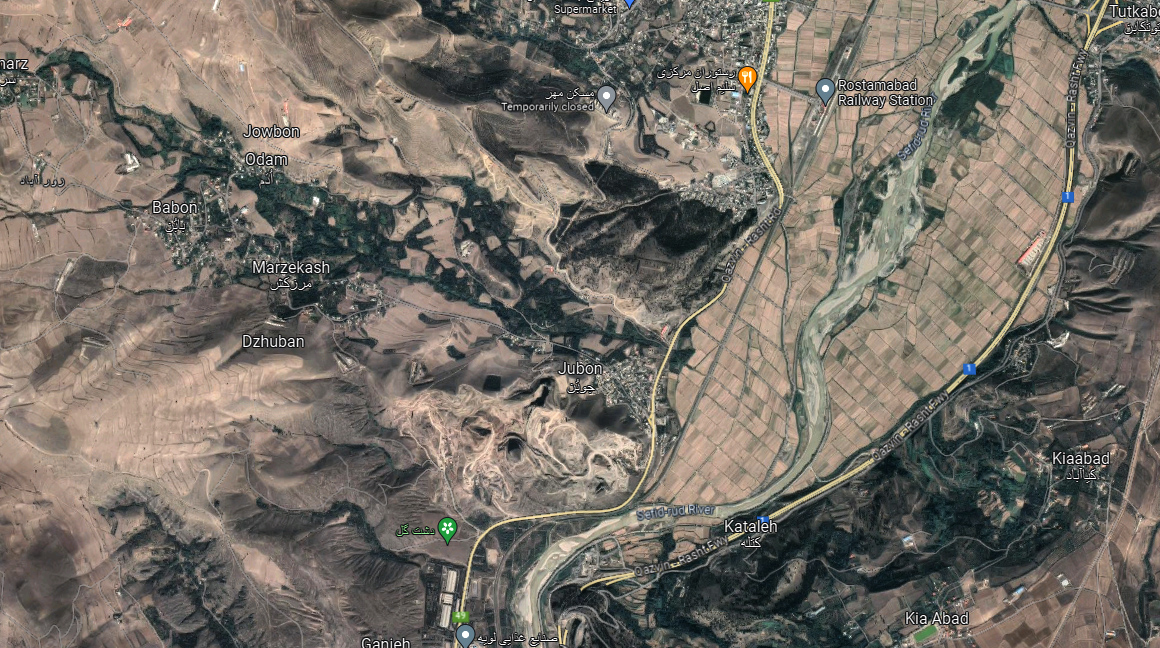

Location: Robāt-e Māhi is 60 km east of Mashhad in northeastern Iran, Razavi Khorasan Province.

36°04’32.4″N 60°21’06.9″E

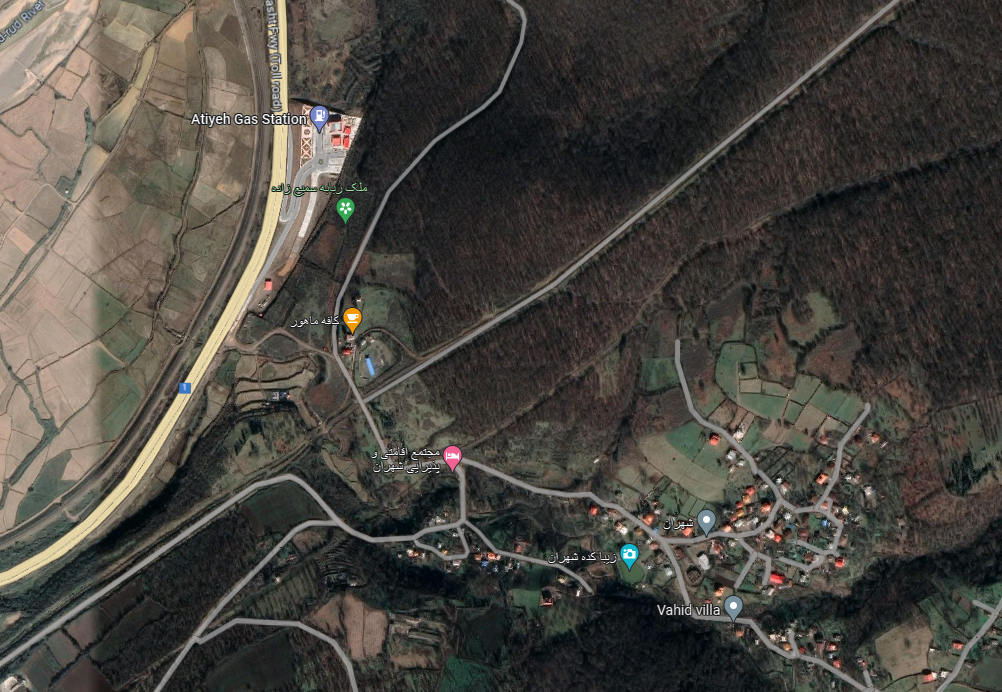

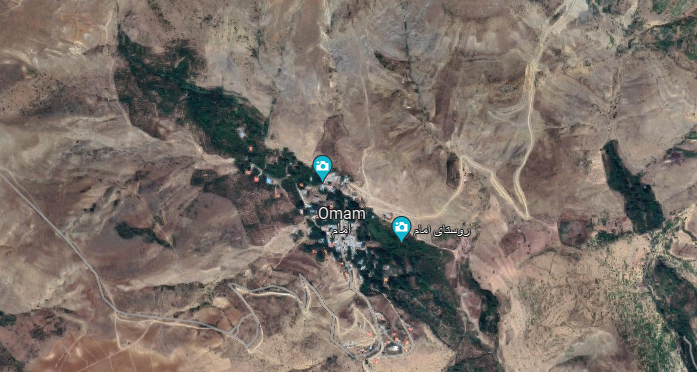

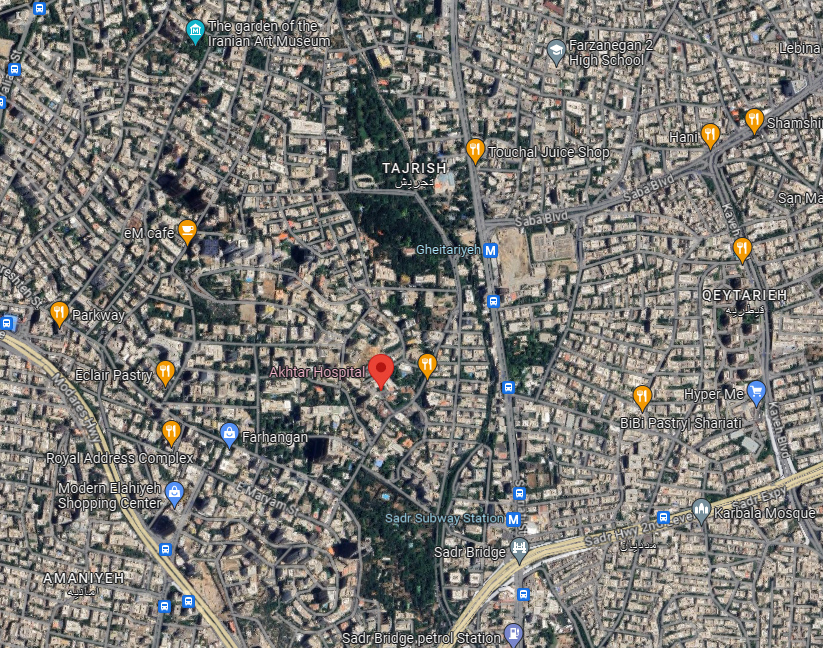

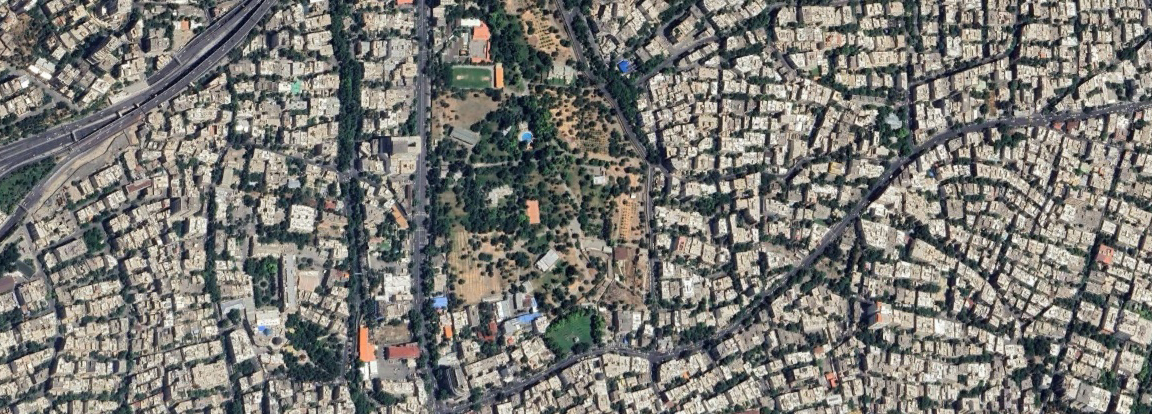

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

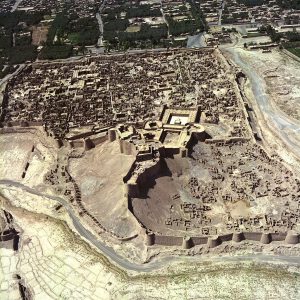

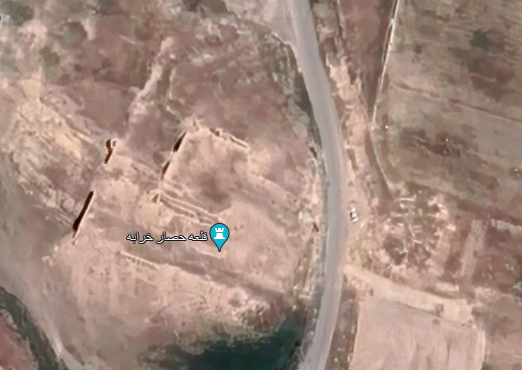

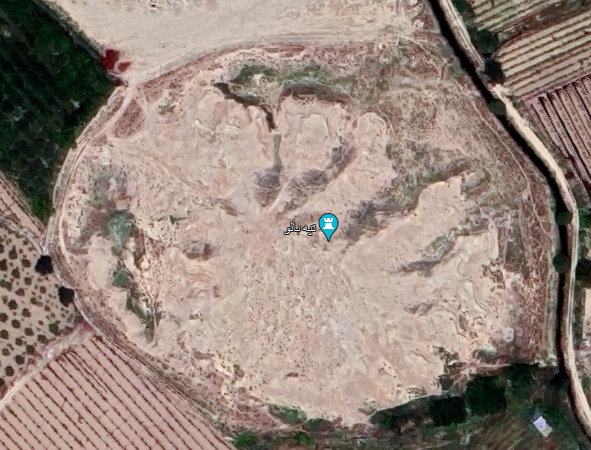

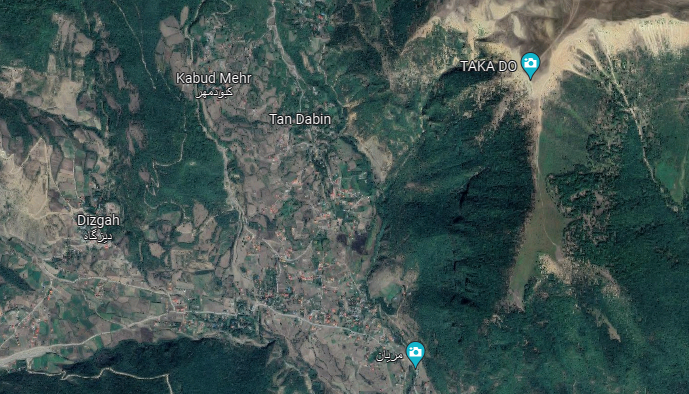

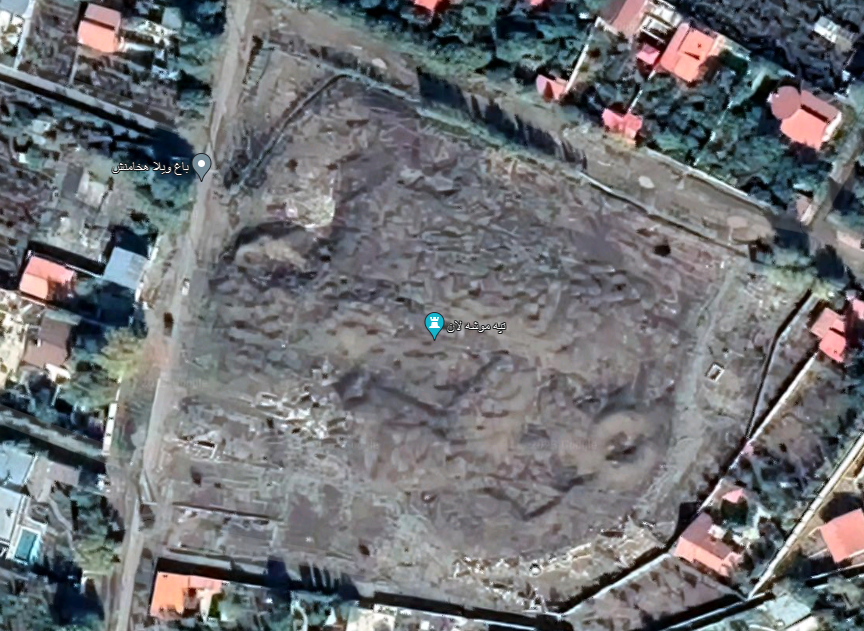

Rōbāt-e Mahi is located on the edge of the Kashfarūd plain, approximately 65 km east of Mashhad and about 4 kilometers from the present-day Mashhad-Sarakhs road. The caravanserai was once part of a chain of lodgings that accommodated travelers and their merchandise on the historical route from Tus to Merv. The ruins of Rōbāt-e Māhi (fig. 1) is located along the east-west route that bypasses Mashhad, extending from Neyshabur through Sangbast and Chāhak—where a rectangular area of ruins to the north of the road likely marks the site of a former caravan station—toward Rōbāt Sharaf, Sarakhs, and Merv. Rōbāt-e Māhi lies north of the Kashaf Rud, next to the remains of an older building of similar function.

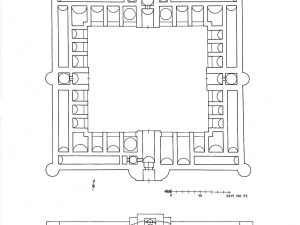

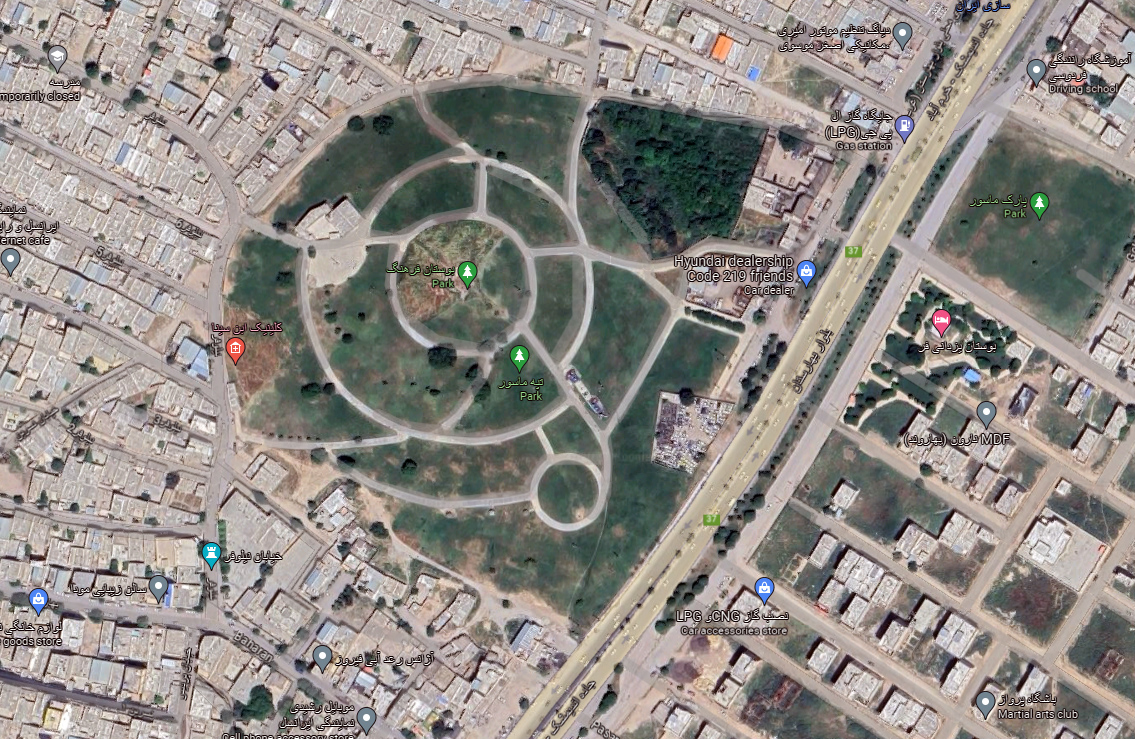

The caravanserai measures 66.50 x 63.40 m encompassing a courtyard that measures 41.20 x 36.40 m (fig. 2). There are four eyvāns, round corner and curtain towers, and a projecting portal structure. It is unclear whether there were arcades surrounding the courtyard. The building follows a square layout, constructed primarily of brick and plaster. On the south side is the main entrance flanked by two semi-cylindrical towers opens onto a four-eyvān courtyard with rooms and chambers arranged around it, and stables situated behind the chambers. The entire caravanserai complex is enclosed by a tall, thick wall reinforced with cylindrical towers. The entrances to the individual rooms, especially the elongated rooms along the outer walls, are no longer clearly identifiable.

In addition to older architectural remains east of the caravanserai, other structures are found around it. On a hill overlooking the caravanserai and the road, there is a tower that appears to have served as a watchtower or road marker. Near the caravanserai, remnants of a large cistern (āb-anbār) also survive.

Either this caravanserai or the nearby ruins near present-day Chāha (also known as Chāhak or Sāhak) is associated with the story of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna’s reward to Ferdowsi. According to Nezami Arūzi, the reward reached Tus after Ferdowsi’s death, and the poet’s daughter refused to accept it. Sultan Mahmud then assigned Khwaja Abu Bakr ibn Ishaq Karami—who had been appointed head of Nishapur by the Sultan—to use the reward money for the restoration of the Chāh-e caravanserai along the Nishapur-to-Marv route.

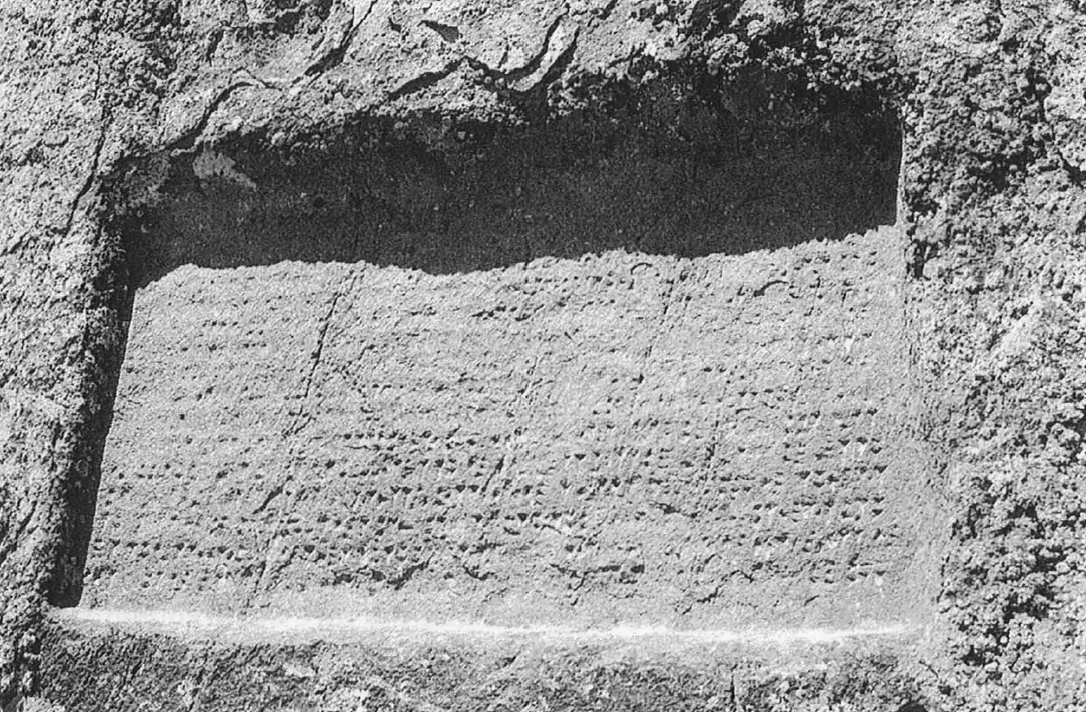

Archaeological Exploration

The name Robāt-e Māhi appears at least once in the 8th century AH/14th century in Hamd-Allāh Mostawfī’s Nuzhat al-Qulub (p. 175), in reference to the itinerary from Nishapur to Sarakhs.Naser al-Din Shah’s brother, Prince Rokn al-Dowla visited the caravanserai in 1299 AH/1882 and referred to the Kufic inscriptions at the site, noting that they were already illegible at that time. Rokn al-Dawla writes that the laymen’s beliefs is that (pp. 62, 71), that the founder of the caravanserai was one of the sisters of Goharshad, the philanthropist wife of Shāhrokh, the Timurid ruler, named Māhī. According to such a belief, the founder of the bridge over the Kashafrud River also known as the Khātūn Bridge was thought to be another of her sisters, named Khātūn. One of the prince’s accompanying offcials, Mohammad Hossein Mohandes, described Robāt-e Māhi as a highly significant ruined structure made of gypsum and brick in his 1311 AH/1893 report. It has been suggested that Robāt-e Māhi was built by a certain Abu’l-Hasan Mohammad ibn Ḥasan Māh, from whom the name Māhi is derived. Ibn Ḥawqal, writing in the latter half of the tenth century, mentions him as a benevolent wealthy man who constructed many caravanserais across Khorasan and Transoxiana.

In recent times, the ruins of Robāt-e Māhi were visited and studied by Mohammad Yusef Kiani and Wolfram Kleiss in the 1980s.

Bibliography

Golbon, M., “Namāy-i az Sarakhs dar dowre-ye Qājar,” Barresihā-ye Tārikhi, No. 48, 1352/1973, p. 139.

Golbon, M. Safarname-ye Rokn al-Dowla, Tehran, 1356/1977, pp. 70-71.

Golchin Arefi, M., “Rōbāt-e Mahi,” Dāneshnāme-ye Jahān-e Eslām/Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, vol. 19, 1393/2014.

Kiani, M. Y., “Kārvānsarāhā-ye jādde-ye abrisham (ostān-e Khorāsān, ostān-e Kermānshāh),” Majmū’eh maqālāt-e kongere-ye tārikh-e me’māri va shahrsāzi-ye Iran, 7-12 esfand 1374, Arg-e Bam, Kerman, vol. 3, Tehran, 1375/1996, p. 610.

Kleiss, W., Karawanenbauten in Iran, vol. 6, Materialien zur Iranischen Archäologie 8, Berlin, 2001, pp. 40-41.

Kiani, M. Y. and W. Kleiss, Iranian Caravanserais, vol. 3, Tehran, 1994, p. 377.

Labbaf Khaniki, R., M. Bakhatiari Shahri, and B. Ne’mati, Kārvānsarāhā-ye Khorāsān, Tehran, 1393/2014, pp. 336-337.

Mostowfi, Hamdullah, The Geographical Part of the Nuzhat-al-qulūb, composed by Hamd-Allāh Mustawfī of Qazwīn in 740 (1340), translated by Guy Le Strange, E. J W. Gibb Memorial series 23, Leyden-London, 1919, p.

Author: Ali Mousavi

Originally published: May 6, 2025

Last updated: June 3, 2025