Radkan East Towerمیل رادکان شرقی

Location: The Radkan East Tower is located 74 kilometers north of Mashhad, in northeastern Iran, Razavi Khorasan Province.

36°46’34.3″N 59°01’53.7″E

Mil-e Radkan

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

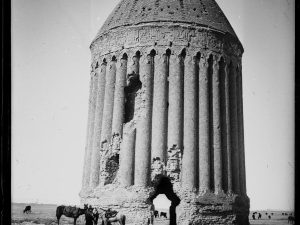

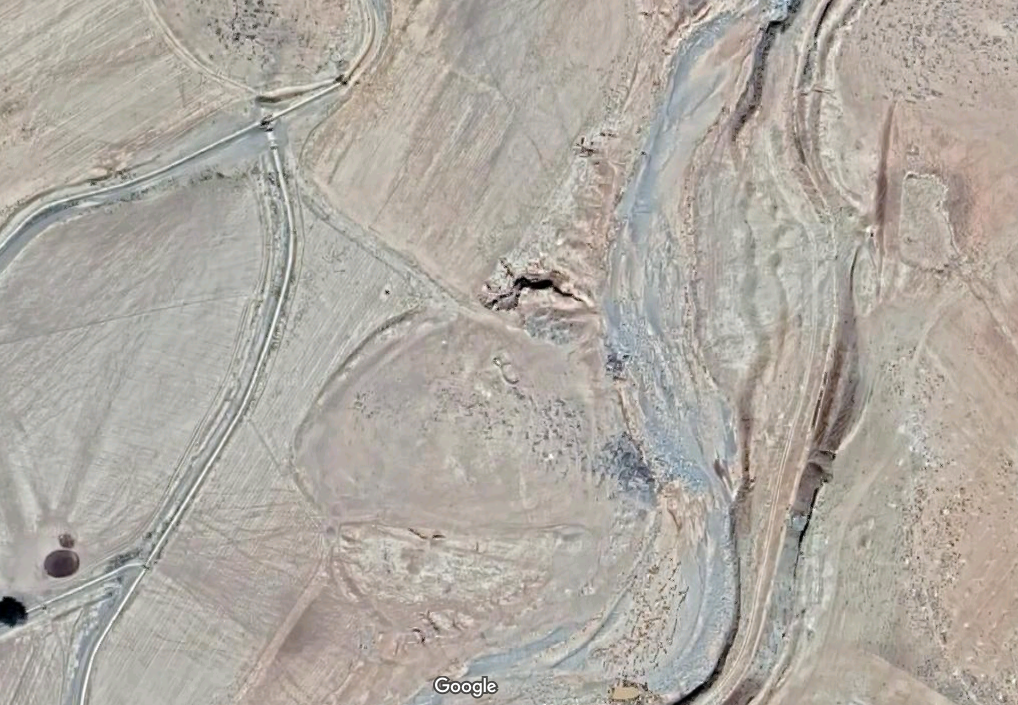

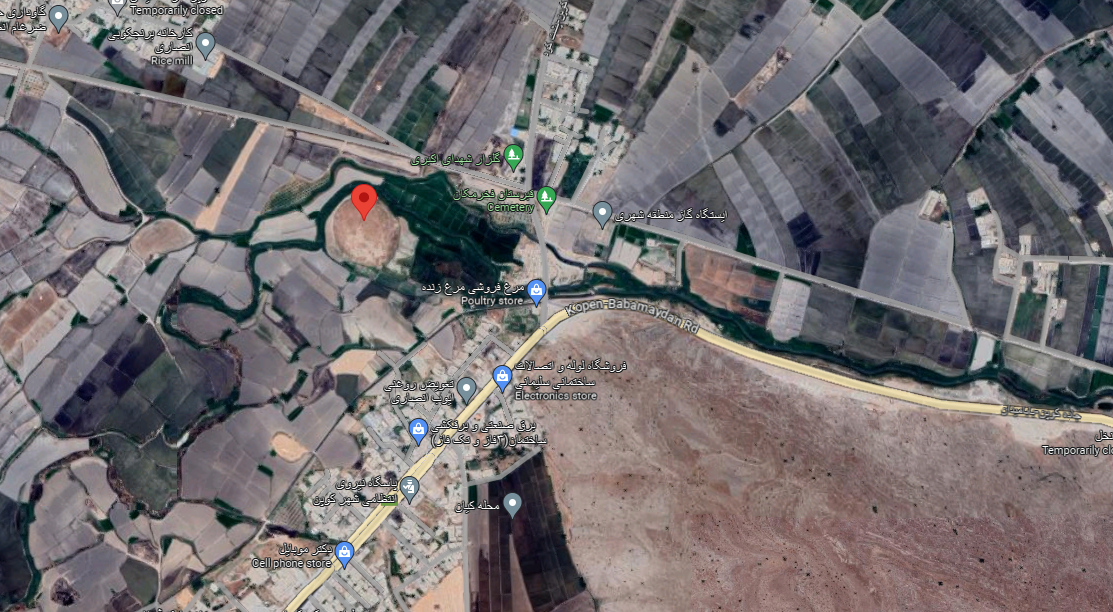

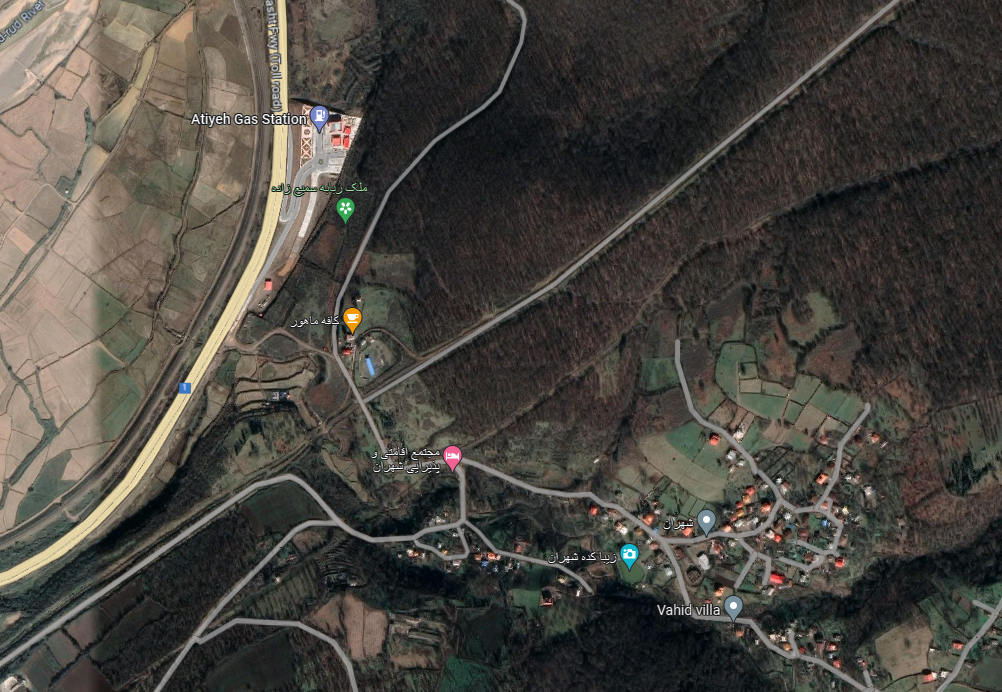

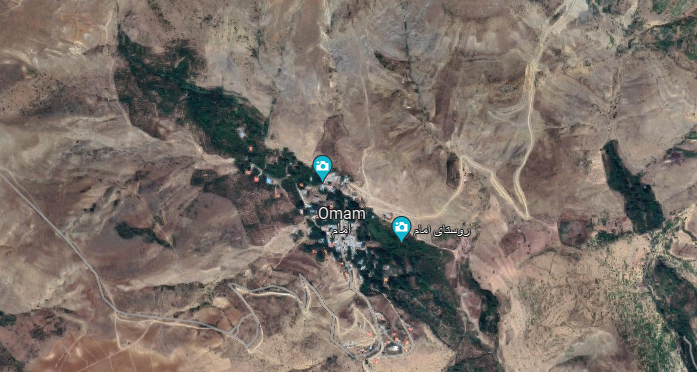

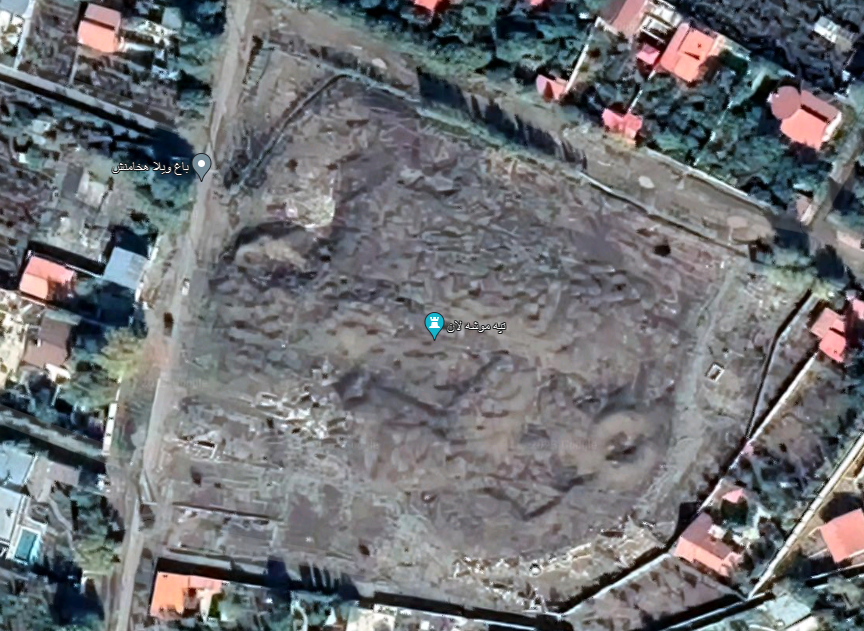

The Rādkan East tower lies 75 km north of Mashhad and 26 kilometers northwest of Chenārān (fig. 1). The tower was in the middle of a vast meadow (ōlang), as mentioned by Juwaini in his Tarikh-e Jahān-Gōshā. The Rādkān meadow stretched for kilometers in length and width, but over the centuries, it was divided into farmlands, reducing its size. Gradually, the meadow’s surface shrank, and what remains is now known as Chaman-e Gāv Bāgh. Fortunately, half of this meadow was endowed by one of the prominent Iranian philanthropists and scholars of the past century, Hossein Malek, to the Malek National Library; the endowment has since saved part of the old meadow. Historically, Ōlang-e Rādkān served as a place to breed and care for royal horses. Several rulers, particularly the Mongol Ilkhāns, traveled to Rādkān for leisure and to inspect their army’s horses. They would stay there to fatten the horses and enjoy the surroundings.

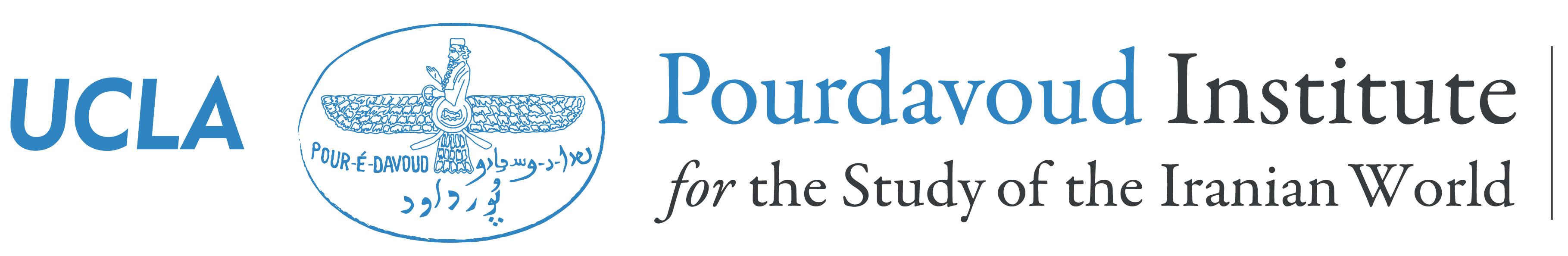

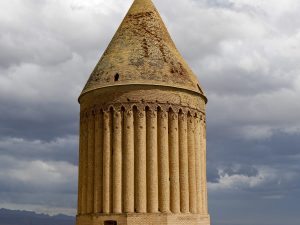

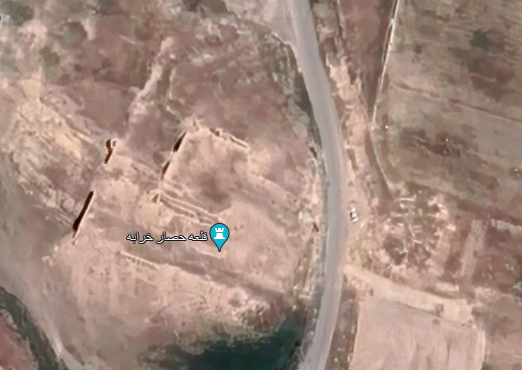

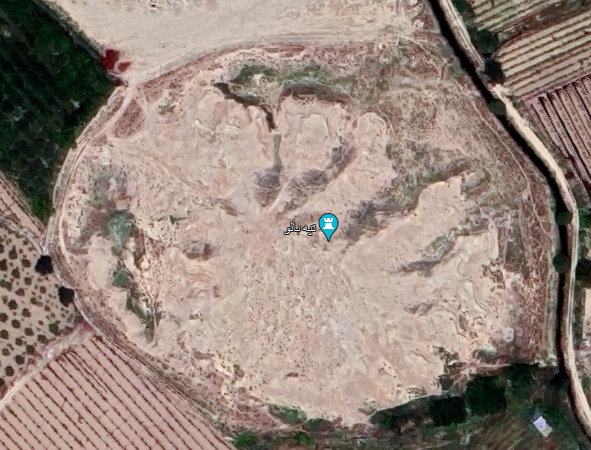

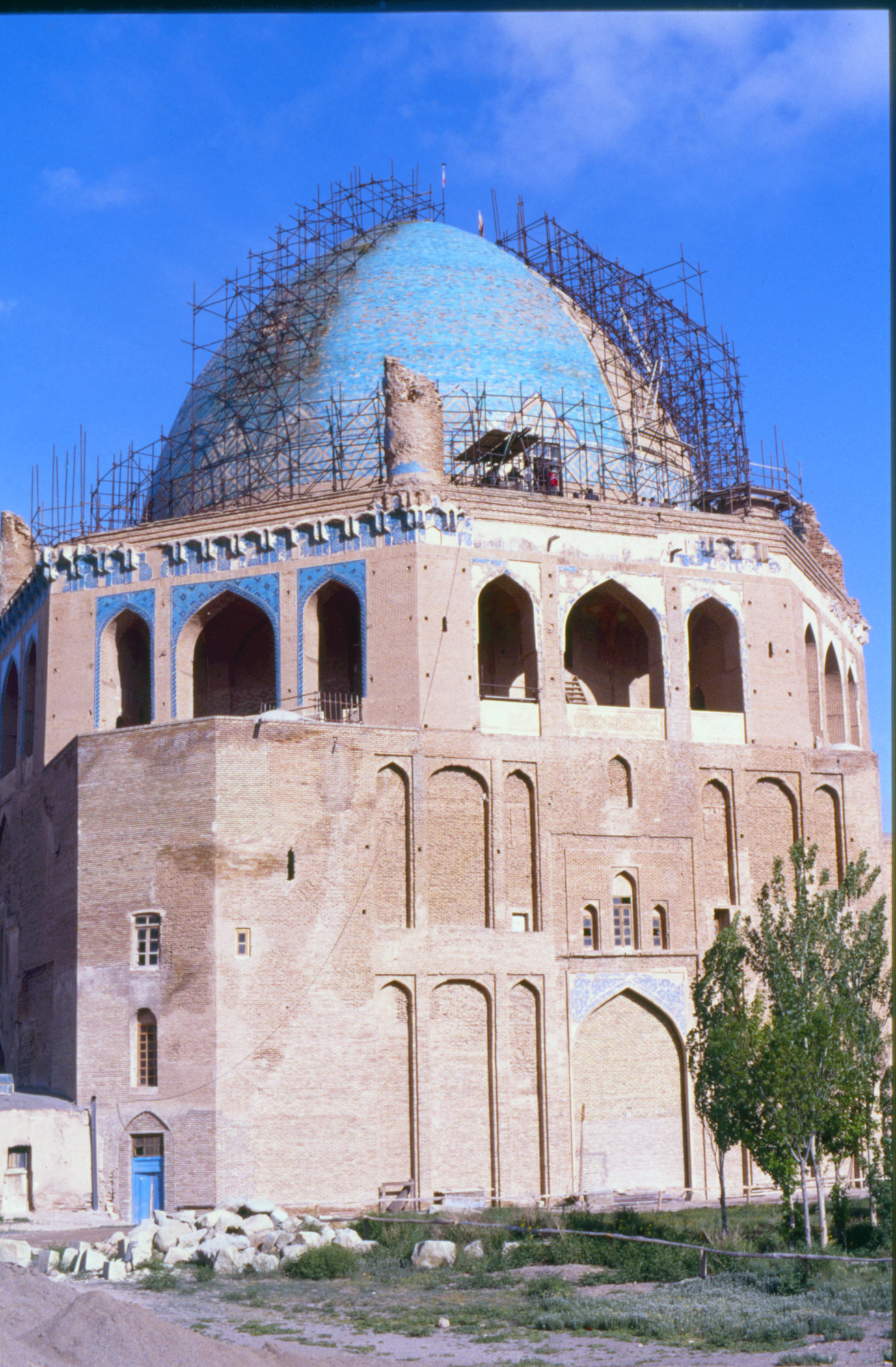

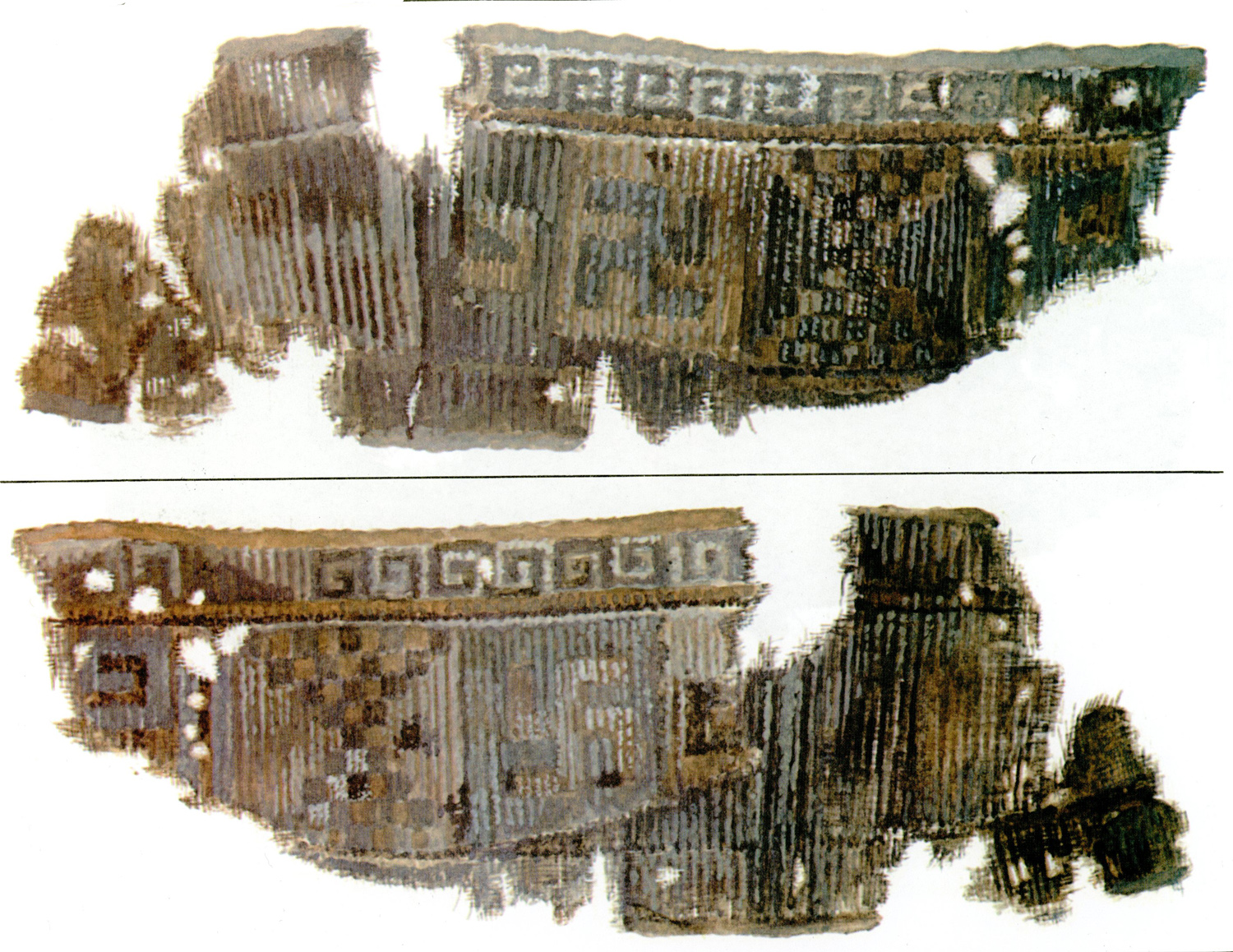

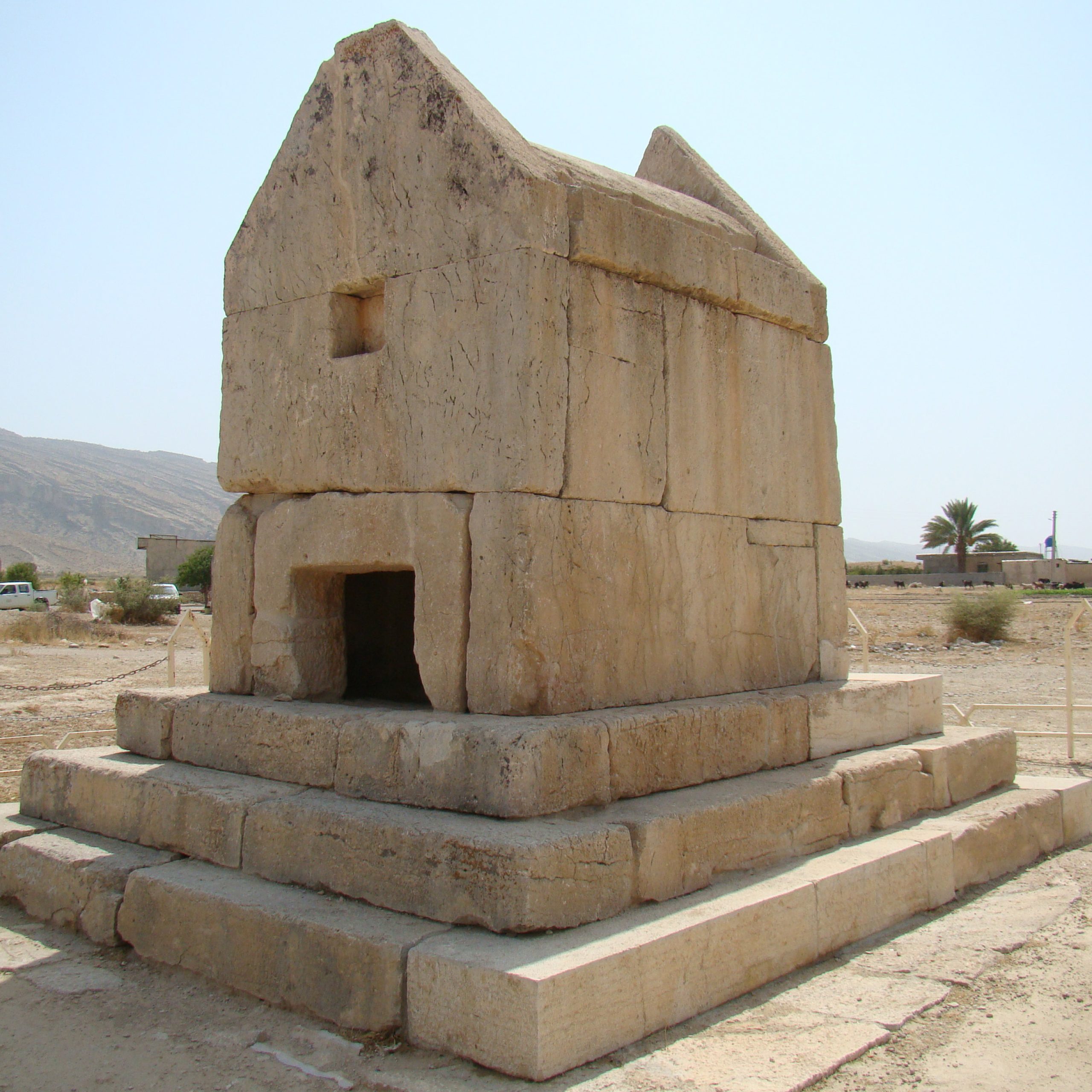

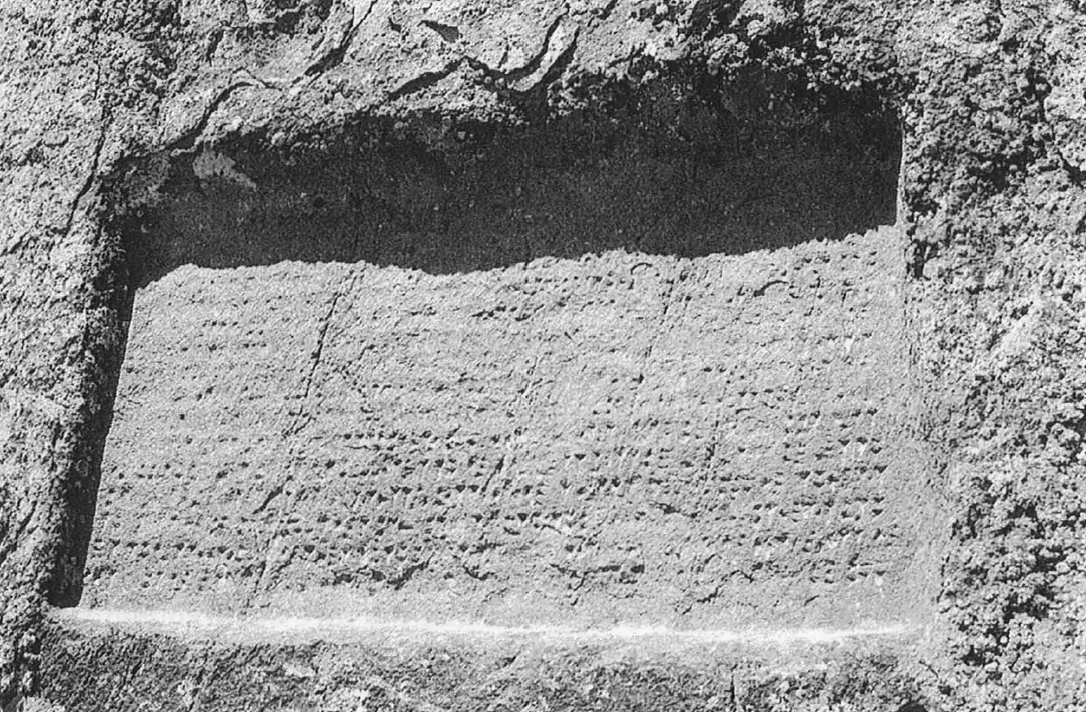

Built in fired brick, the tower is 22 m high, with an internal diameter of 14 m. and an external diameter of 20 m. The Rādkān tower has a cylindrical body and a conical dome. The exterior of the structure is 12-sided up to a height of 3 meters, above which it transitions to 36 semi-columned flutes up to an inscribed band below the conical dome (fig. 2). There are two opposing entrances on the east and west sides of the tower. The interior is octagonal up to the height of the roof. The walls are plastered and unadorned. A formerly sealed, now exposed inter-mural spiral staircase—revealed through an external wall opening above the base—leads up to the inner base of the roof. High on the cylindrical section, just beneath the cornice of the conical superstructure, runs a band bearing an inscription in square Kufic script (fig. 3). The large letters are formed from inlaid and interconnected stucco panels, once covered with a blue glaze. Although the inscription had previously been observed and studied, the preservation state of the inscription offers very little possibility for a clear reading.

The main issue regarding the dating of the monument lies in the fact that the date of the inscription is damaged. Its stylistic features suggest it was written after 1200 A.D. In the first thorough study of the inscription, Max van Berchem proposed a date of 602 H. /1205 or 1206. Ernst Herzfeld, rejecting the early dating of the text, argued that the tower served as the mausoleum of Amir Arghūn, who was stationed at Rādkān and died there in 1274 A.D. Herzfeld dates the monument to 680 H. /1281 or 1282. Amir Arghūn’s association with Rādkān is mentioned in contemporary sources such as Tarikh-e Benakati, Tarikh-e Jahan-Gōshā, and Jam’eh al-Tavarikh. The inscription is written primarily in Persian. Art historian Sheila Blair believed she could discern the name “Amir Abdallah,” an otherwise unknown ruler of Rādkān. However, a more precise transcription during the restoration work in 1968 revealed part of the name “Arghūn.” Based on this, Abdolhamid Mowlavi interpreted the inscription as referring to “Amir Adel Argh[ūn]. ” The inscription also mentions the name of the tower’s builder as a certain Abu Bakr Zangi Herawi.

The Iranian writer and scholar, Manouchehr Arian, believes that the Rādkān Tower is the same as the Zadak Tower attributed to Khwaja Nasir al-Din al-Tusi—a structure with astronomical functions that was built in the year 600 H. for calendar calculation. His claim is based on field research, calculations, and the writings of Hafez Abru. According to Hafez Abru Khwaja Nasir built a tower in the village of Zadak with twelve windows. During each new moon, the moon could be seen through one of the windows of the tower.

Archaeological Exploration

Archaeological exploration:

In modern times, the Rādkān tower was first mentioned briefly by the British traveler James Baillie Fraser, who observed it from a distance in March 1822. In June 1848, Xavier Hommaire de Hell, the French traveler, examined the tower and inscription. Without describing the monument, he copied the inscription under the dome, which he published in the supplemental Atlas of his travel account. A reproduction of Hommaire de Hell’s drawing can be found in Henri-René d’Allemagne’s travel book (see bibliography). Then, in 1876, George Campbell Napier, a British Army officer, visited the tower and identified the Kufic inscription under the dome, noting that it was “much defaced, especially on the north side, where it must be illegible.” Another British traveler, Edmond O’Donovan—mistaking it for the “primitive form of a mosque”—gives a long description of the ruined tower in 1881In 1884, Mohammad Hasan Khan Etemad al-Saltaneh, a prominent Iranian writer and high-ranking official of the Qajar era, considered the structure to be the tomb of a notable of the Daylamid dynasty. Etemad al-Slataneh mentions that the bones of a “hairy elephant” (or mammoth) had been discovered at Rādkān, along with the animal’s teeth, which were reportedly presented to the Shah. He then entrusted them to his French physician, Dr. Tholozan, in whose library in Tehran they were said to have been kept. The rest of the story is given by Colonel Charles Edward Yate of the British Army, who visited Rādkān in 1884 (Yate, Khurasan and Sistan, p. 365):

I inquired about this, and Muhammad Ibrahim Khan sent a man to show me the place where the bones were found. The man took me down a walled lane by the side of a small nullah through the gardens at the south of the town, and described to us how some forty or forty-five years before, when a boy of ten or twelve years of age, he and two others were returning home from some village out in the valley when they saw a great bone sticking out from a hollow in the ground that had been washed out by a flood of water… They carried the bones to Radkhan, where they soon broke up, and the pieces were dispersed and lost. Nothing was preserved but two teeth, … The man described the skull, which he said was perfect when first taken out, and he declared, and stuck to it, that it had one horn which came out of the middle of the top of the head.

The identification of the tower seems to preoccupy Yate as he continues:

Whether it was constructed as a mausoleum or what, it is impossible to say. One tradition ascribes it to Sultan Sanjar. Another idea is that it was built by Alp Arslan (1063), who held a great assembly of all his nobles, governors, and chiefs at Radkhan to announce the appointment of his son, Malik Shah, as his heir-apparent. A third report is that it is the mausoleum of Amir Arghun Agha, a Mongol noble, who was sent to Khurasan by Uktai Khan, the son of Changiz Khan, to repair the damage done by his father. Arghun Agha made Radkhan his headquarters and died in 1274.

Henri René D’Allemagne, who traveled in the region in the early years of the twentieth century, writes about the tower as follows (Du Khorassan au pays des Backhtiaris III, p. 70):

Cette tour, dénommée Mil-i-Radkan, est de forme conique et sa construction remonte à la conquête de la Perse par les Arabes. Les murs extérieurs sont complètement ondulés et semblent être formés de nombreuses colonnes cannelées qui seraient Presque jointives. Ce monument est couronné par un immense foit conique, au-dessous duquel se développe une gigantesque inscription en caractères coufiques tracés à l’aide de briques émaillées bleues. Originairement l’intérieur de la tour était divisé en trois étages aujourd’hui effondrés.

In 1908, while traveling in northern Khorasan in the autumn of 1908, Major Percy Sykes visited Mil-e Rādkān and, among many accounts identifying the tomb’s owner, he preferred the one, “according to which it is the tomb of Arghun, termed Argawan by the Persians, who was closely connected with Khorasan and has given his name to one of the natural portals of Kalat-i-Nadiri.”

A more comprehensive study of the monument was conducted in 1911, when Austrian art historian and traveler Ernst Diez visited Khorasan. Diez provided a detailed description of the ruined tower, and the analysis of its inscription, entrusted to Max van Berchem, has since remained a foundational source for the study of the monument. In the years leading up to World War I, Henry Viollet, the French art historian and traveler, captured the first clear photographs of the tower (fig. 4). In 1922, Ernst Herzfeld visited the Rādkān tower and published a detailed study of its inscription, identifying it as the tomb of Amir Arghūn Aghā. Robert Byron, who visited the tower in 1934, took photographs and recorded the monument as follows (Byron, Road to Oxiana, p. 239):

…a massive cylindrical gravetower with a conical roof, ninety feet high, and dating from the thirteenth century. The outside wall consists of columns two feet thick, which touch one another. Their brickwork, rusty red in colour, is arranged in tweed patterns, which give the building a sort of shine, as of a well-groomed horse. Unlike the Gumbad-i-Kabus, this tower has a staircase in the thickness of the wall.

In 1968, the Khorasan branch of the Ministry of Culture and Arts undertook major restoration work on the tower. The project was led by Yaghub Danesh-Doust, a talented Iranian architect of historical monuments.

Bibliography

Arian, M., Negāhi digar be borjhā, Tehran, 1384/2005, pp. 12-14.

Blair, Sh. S., “The Madrasa at Zuzan: Islamic Architecture in Eastern Iran on the Eve of the Mongol Invasions,” Muqarnas, vol. 3, 1985, pp. 87 and 90, note 91.

Byron, R., Road to Oxiana, London, 1937, p. 239.

Etemad-al-Saltaneh, M. H., Matl’a al-Shams, vol. 1, Tehran, 1301 H/1884, reprint 1362 /1983, pp. 175-176.

D’Allemagne, H. R., Du Khorassan au pays des Backhtiaris. Trois mois de voyage en Perse, Paris, 1911, vol. 3, pp. 69-70.

Diez, E., Die Churasaniche Baudenmäler, Berlin, 1911, pp. 43-46, 107-109, pls. 6-8

Fraser, J. B., Narrative of A Journey into Khorasan, in the Years 1821 and 1825, London, 1925, p. 552.

Herzfeld, E., “Die Gumbadh-i ʿAlawiyyān und die Baukunst der Ilkhane im Iran,” in Ajab Nama. A Volume of Oriental Studies Presented to Edward G. Browne on His 60th Birthday (7 February 1922), edited by T. W. Arnold and R. A. Nicholson, Cambridge, 1922, pp. 192-193.

Hommaire de Hell, X., Voyage en Turquie et en Perse exécuté par ordre du gouvernement français, vol. 3, Paris, 1856, pp. 297 and 301; Atlas, plate LXXXV.

Mowlavi, A., “Gūrābe-ye Amir Arghūn Aghā,” in Majmūm’eh maqālāt-e nakhostin kongere-ye tahqiqāt-e irani, edited by M. Sotudeh, vol. 3, Tehran, 1354/1974, pp. 65-92.

Napier, G. C., “Extracts from a Diary of a Tour in Khorassan, and Notes on the Eastern Alburz Tract,” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 46, 1876, p. 84.

O’Donovan, E., The Merve Oasis, vol. 2, London, 1882, pp. 22-24.

Sykes, P. M., “The Sixth Journey in Persia,” The Geographical Journal, vol. 37, No. 1, January 1911, p. 2.

Wilber, D. N., The Architecture of Islamic Iran: The Il Khanid Period, New York, 1969, pp. 116-117.