Qal’eh Zohāk/Qal’eh Zahāk, Nārin Qal’ehقلعه زهاک، نارین قلعه

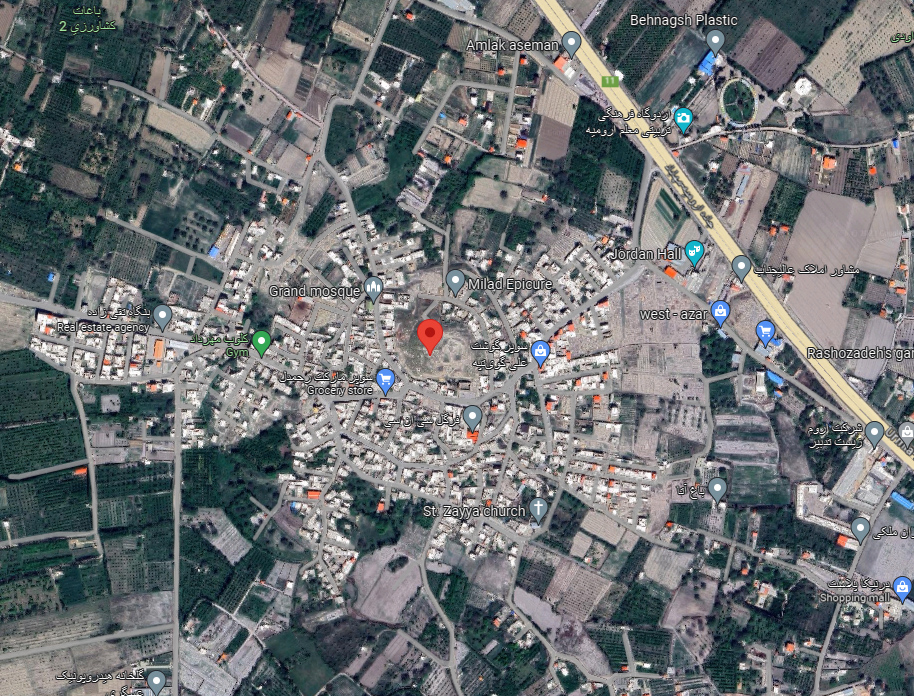

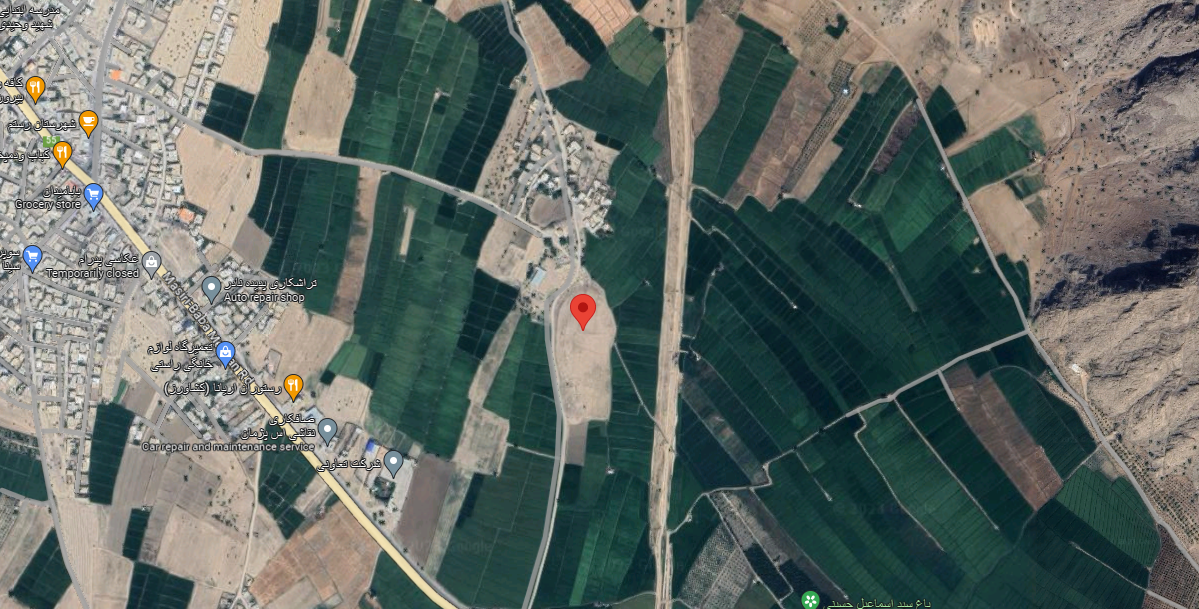

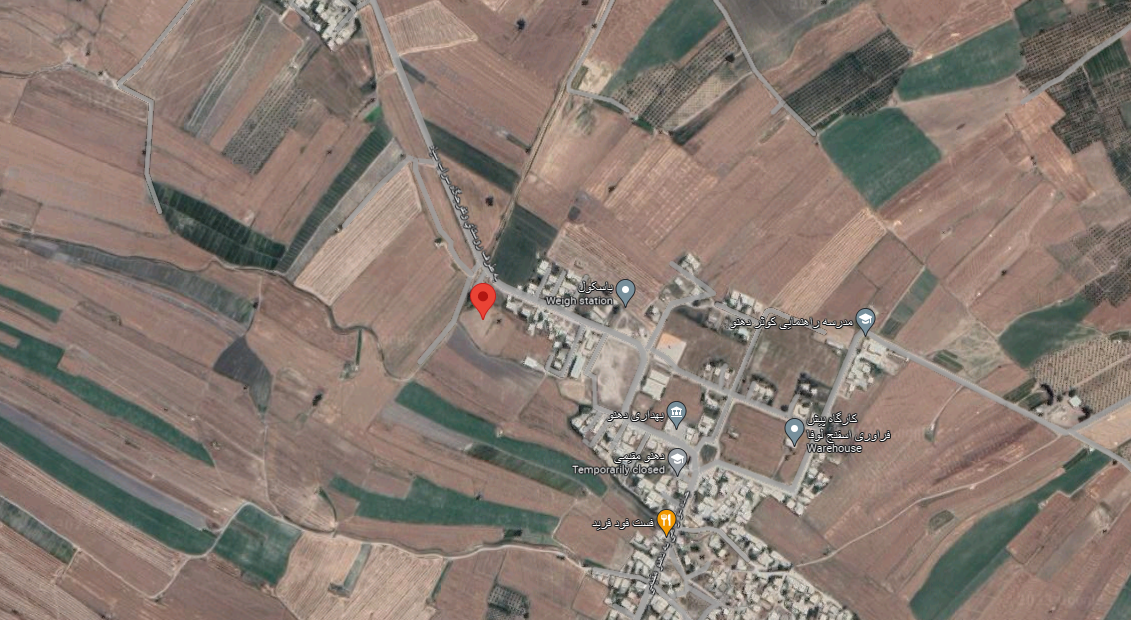

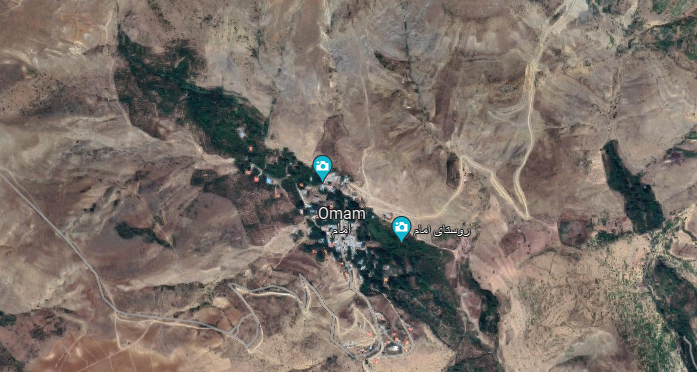

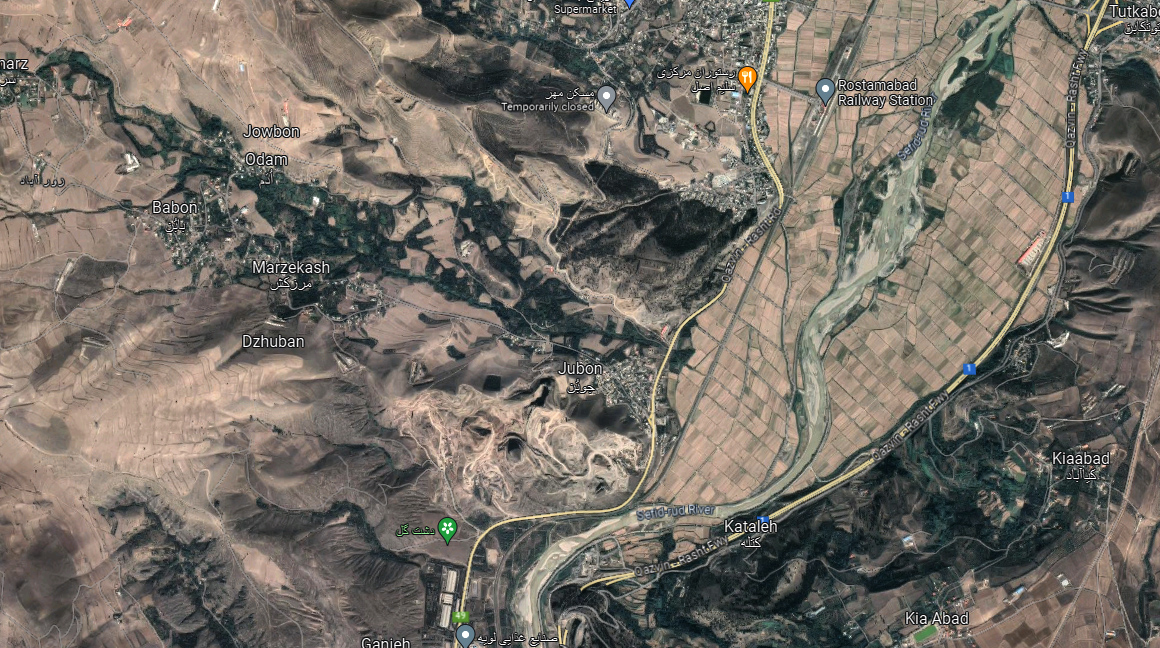

Location: Qal’eh Zohāk is located 65 km west of Miyāneh, in northwestern Iran, East Azarbaijan Province.

37°23’9.02″N 47°10’5.98″E

Location:

Historical Period:

Parthian – Sasanian (100 B.C. – 651 A.D.)

History and Description:

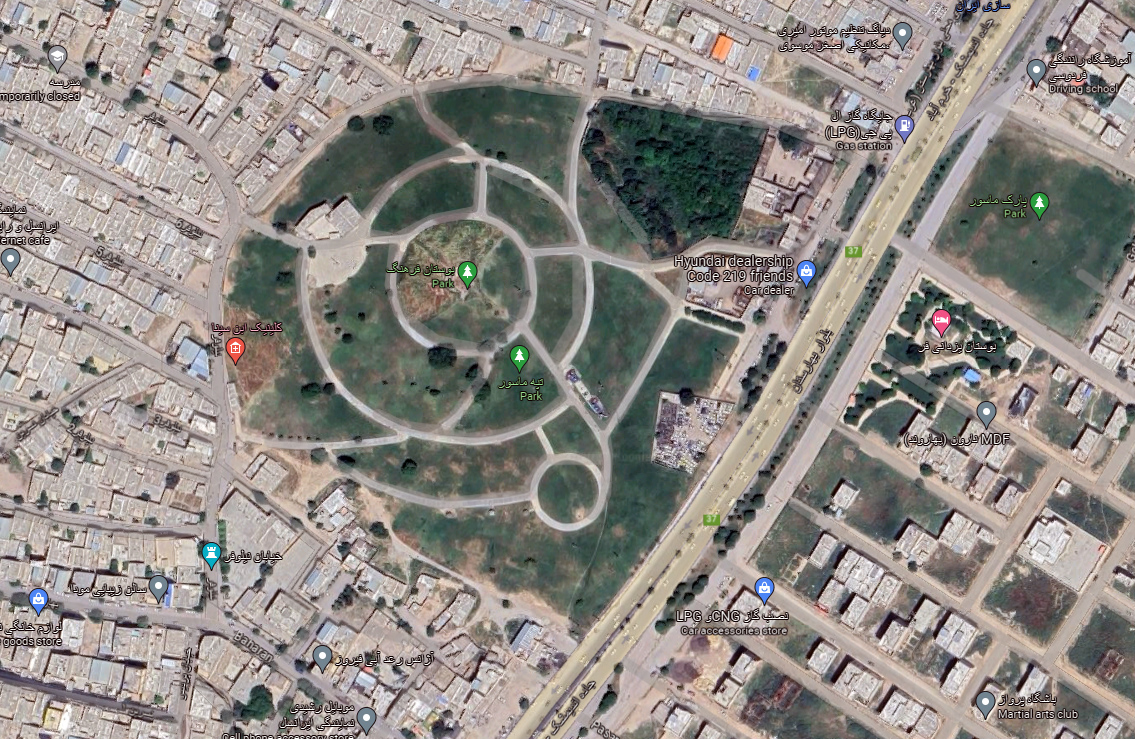

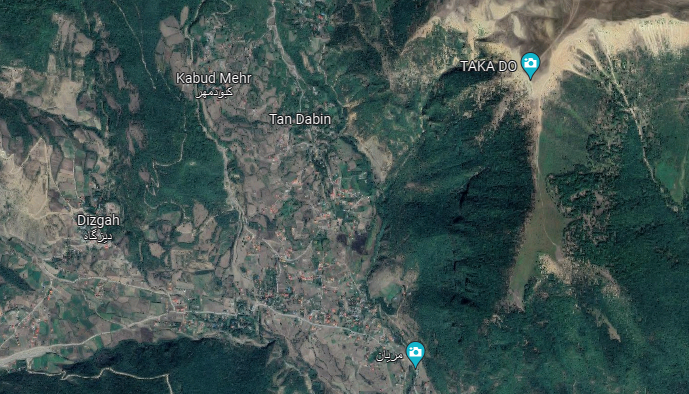

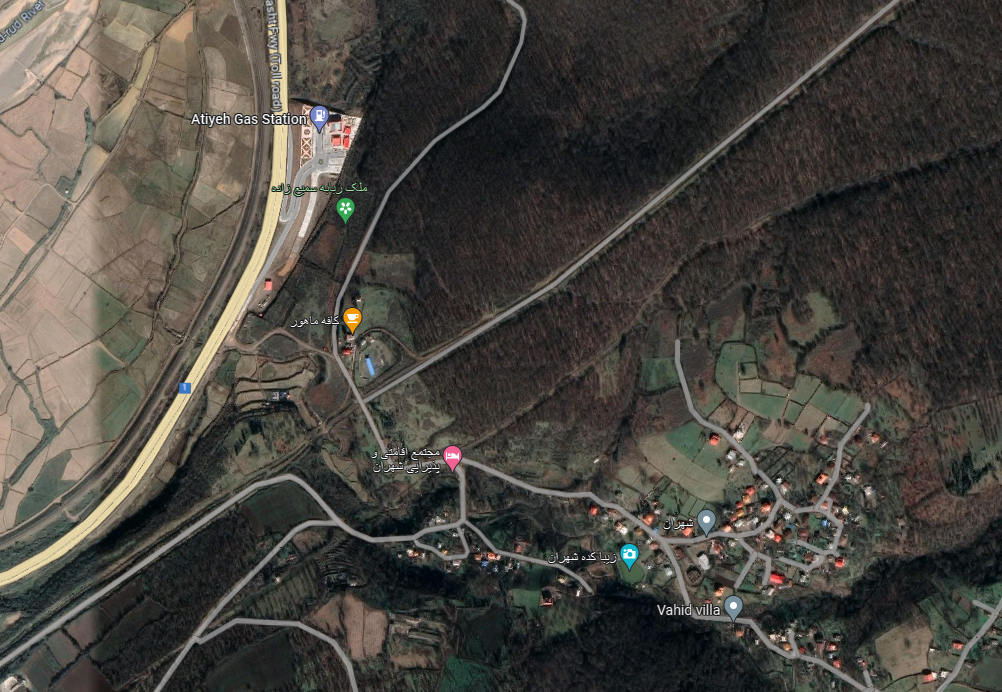

Qal’eh Zohāk is located between Miyāneh and Marāgheh. About 65 km west of Miyāneh, at Siāh Chamān, on the main road Miāneh-Tabriz, a bifurcation leads to the town of Hashtrūd (formerly Sareskand) 21 km to the south. After driving 16 km to the south/southwest, one reaches the Khorāsānak railroad station. From the station, a 2-hour march leads the visitor to the top of the site. The only historical mention of the site is in Ptolemy’s Geography, based on which Vladimir Minorsky identified Qal’eh Zohāk with Phānaspa (Minorsky, “Roman and Byzantine Campaigns in Atropatene,” p. 262, footnote 1). Qal’eh Zohāk is the only large fortress in the region between Zanjān and Marāgheh. It could be the best candidate for the site of Phānaspa and its geographical situation supports such a claim.

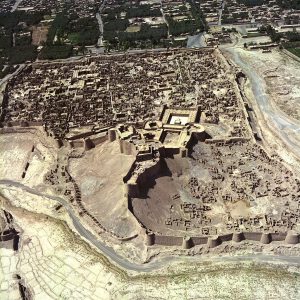

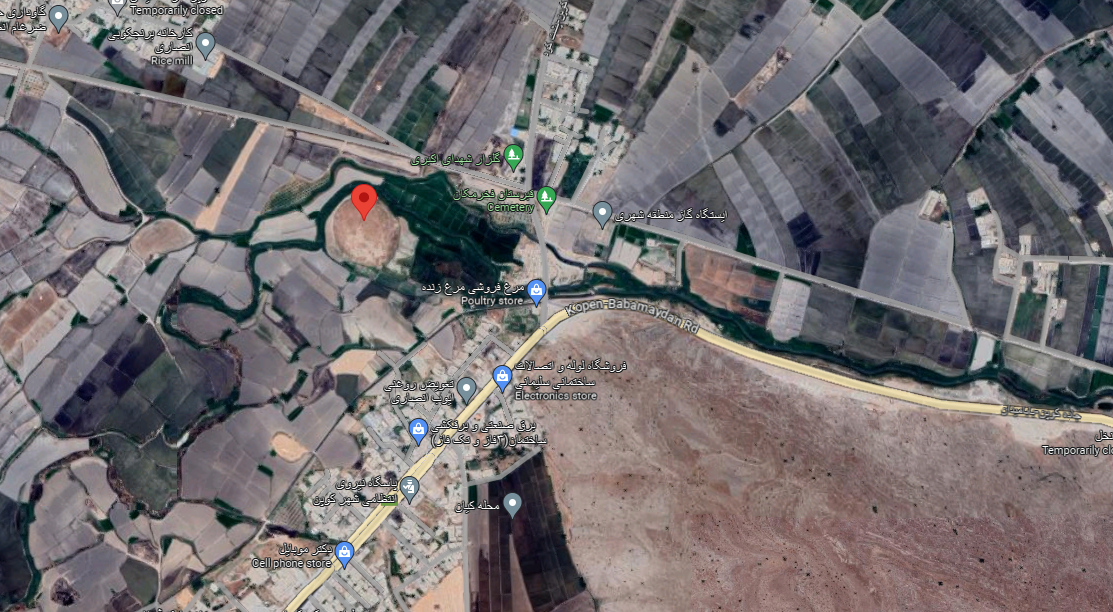

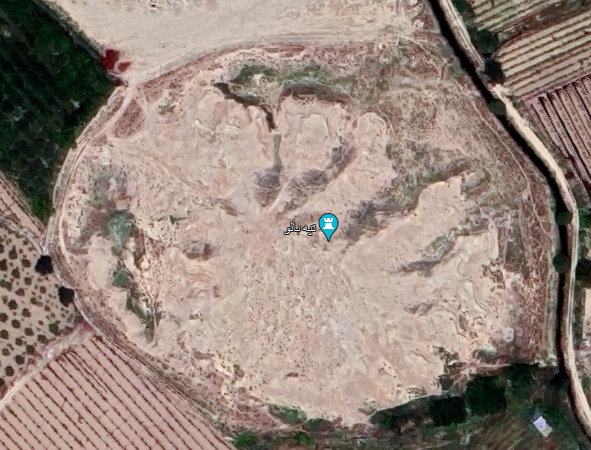

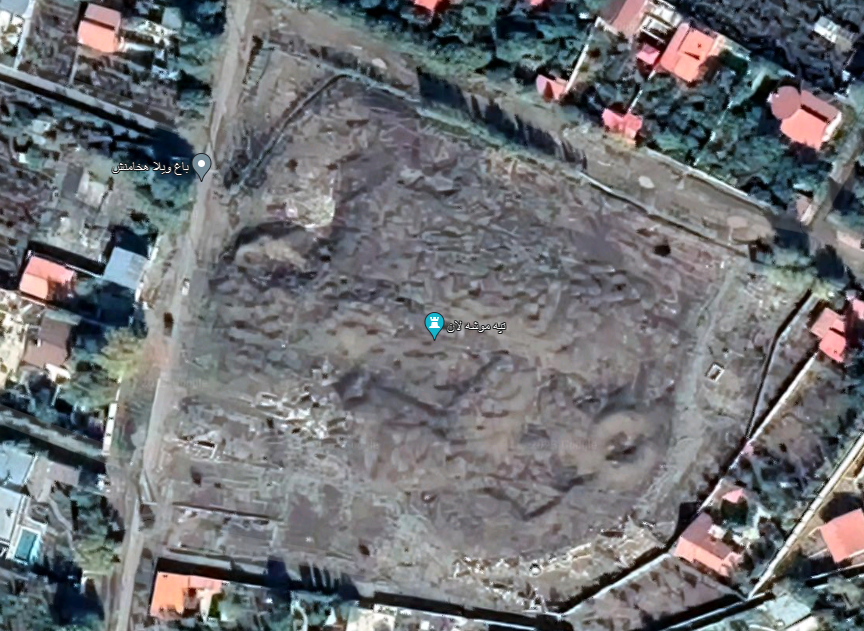

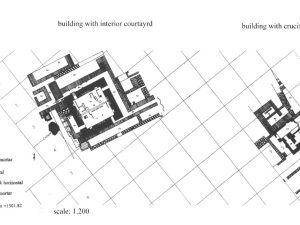

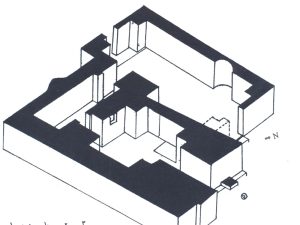

The ruins of Qal'eh Zohāk lie on a promontory (fig.1). The two perennial rivers, the Qarānqū and the Shūrchāy, encircling the promontory, form a well-defended peninsula. The layout of the site consists of two hills and a connecting saddle. The total expanse of the occupied area is about 1 km north-south. A massive fortress in the south built on the slope of the mountain protects the site (fig.2) To the north of the fort, lie the ruins of a settlement. Another series of walls separates this area from the relatively densely built northern sector where three groups of structures have so far been explored.

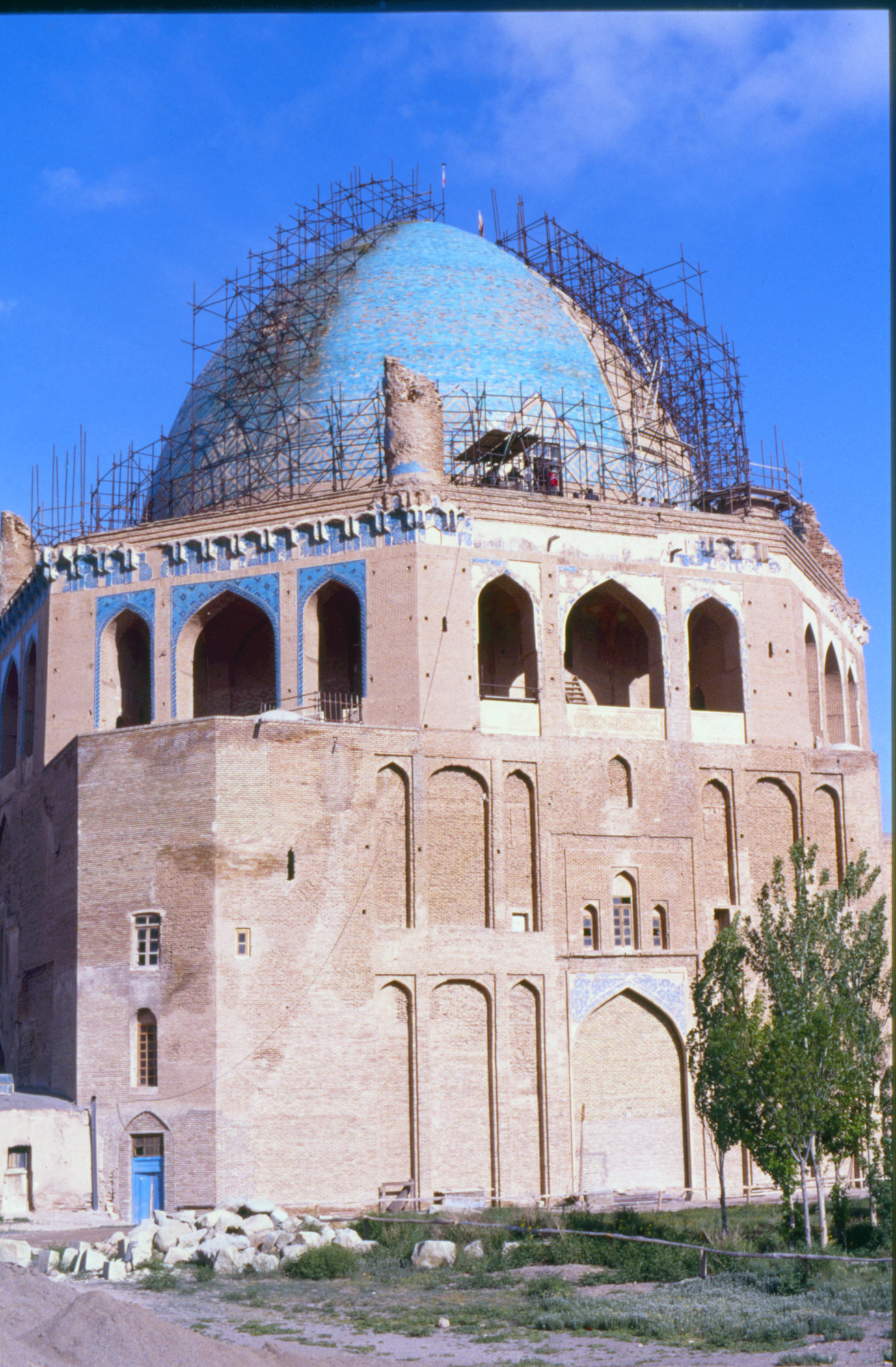

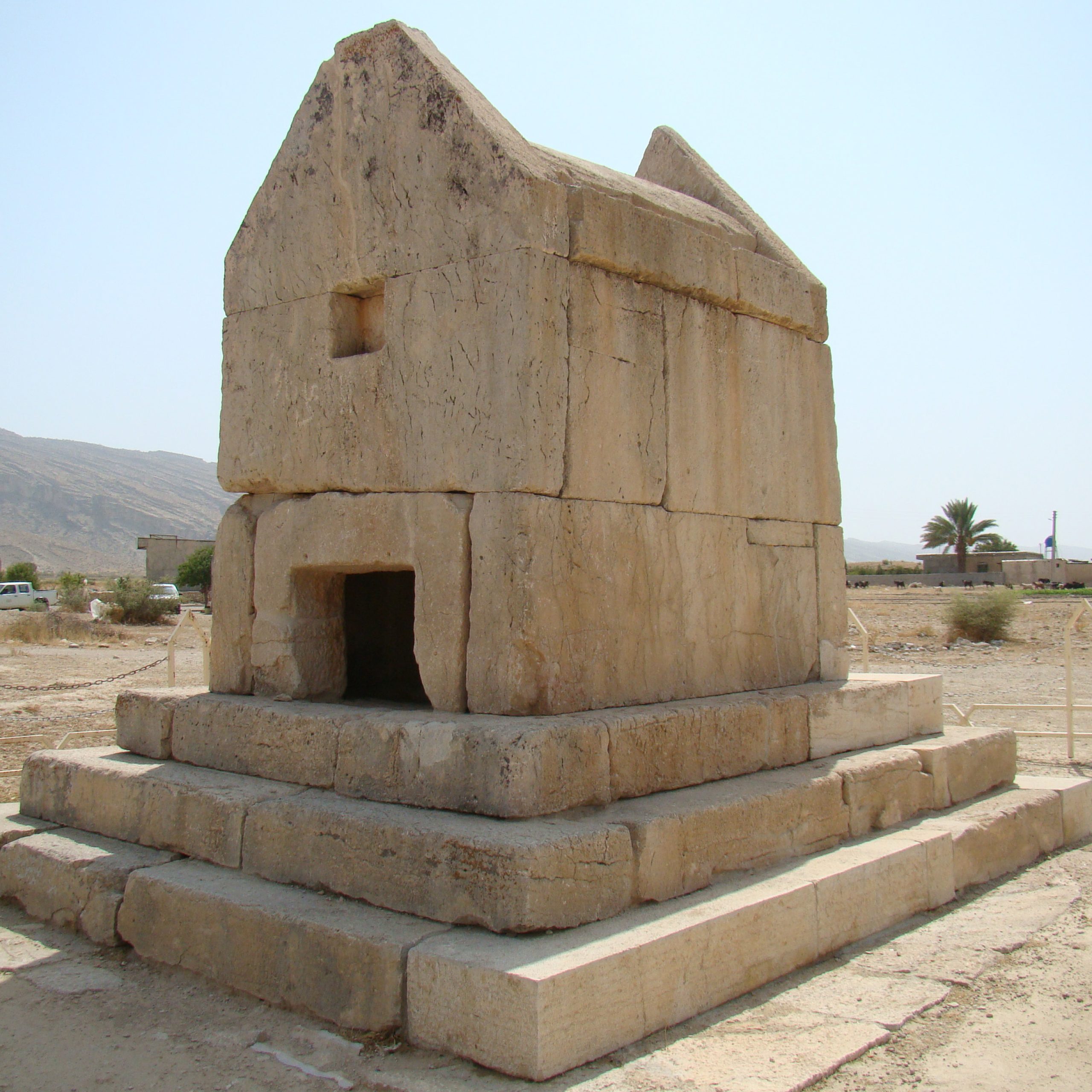

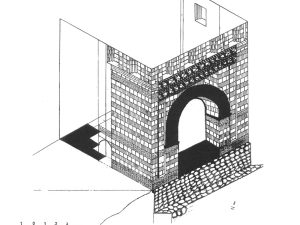

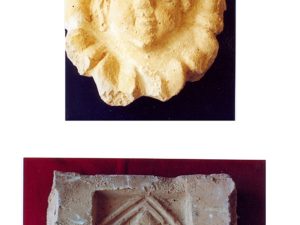

1. The Pavilion (fig.3, fig.4, fig.5, fig.6, fig.7): The four-arched structure known as a pavilion sits on a platform of stone on the edge of the cliff. The foundations are in stone with mortar used as binding; the superstructures were all in burnt brick. From the exterior, the square pavilion measures 9.20 m x 9.50 m. The monument was originally more than 12 m high and was crowned with crenelations (fig.8). The arches, 7.5 m high each, were decorated with stuccoes depicting floral motifs or swastikas and inscribed panels (Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” pp. 63-64). The Qal’eh Zohāk Pavilion is quite unique in Iran. The closest comparable structure to the Qal’eh Zohāk pavilion is the first century B.C. ruined Memmius Monument at Ephesus in Asia Minor (Pohanka, “Zum Bautyp des Pavilion von Qal’eh Zohāk,” p. 244); a later example of such pavilions is the Sasanian pavilion known as Taq-e Garrā between Sar-e Pol-e Zohāb and Qasr-e Shirin as well as the sculptured grottos or eyvāns at Taq-e Bostān (Vanden Berghe, Archéologie de l’Iran ancien, p. 103, pl. 126; Pohanka, “Zum Bautyp des Pavilion von Qal’eh Zohāk,” p. 252).

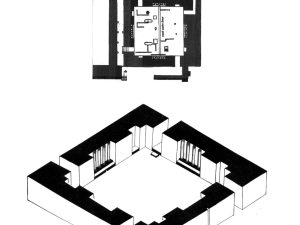

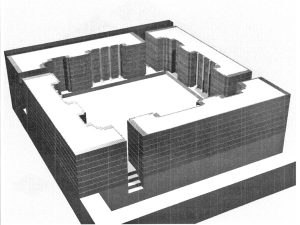

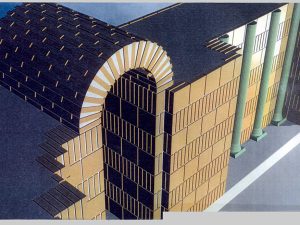

2. The Hall or the building with interior courtyard (fig.9, fig.10, fig.11, fig.12): The recent excavations uncovered an architectural complex with a central hall to the south/southeast of the Pavilion. The square hall (15.5 m on each side) was built on a stone platform. The interior was decorated with niches and stuccoes. According to the excavator, who compares this building with the subterranean temple at Bīshāpūr, the central hall of the complex had no roof. It is not clear if it served as a temple or a palace or both (Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” p. 67, fig. 10). Derakhshi’s reconstruction shows some of the Hall’s architectural features and decoration such as barrel vaults in brick, engaged columns, and possible decoration with stuccoes.

3. The Swastika building or the building with a cruciform hall (fig.13): The excavations revealed a series of structures to the east of the Hall. The most characteristic construction here is a building with a cruciform hall, 4 x 4 m. (Qandgar, J., Esma‘ili, H., and Rahmatpour, M., “Kāvoshhā-ye Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtrūd, ” p. 198; Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” p. 80).

The Sasanian occupation of the higher parts of the southern area seems to be short-lived and secondary. The fortress at Qal'eh Zohāk was gradually abandoned in the early Islamic period, possibly in the tenth century as no trace of violent destruction has been detected in archaeological excavations (Derakhshi and Khademi Nadooshan, “The Chronological Occupations of Zahak Castle on the Basis of Three Seasons of Excavations (2000-2002),” p. 41).

Fig. 1. Qal’eh Zohāk. General view of the fortress (photo: Max Damberger. https://www.maxblog.at).

Fig. 2. Topographic plan of Qal’eh Zohāk (after Kleiss, “Qal’eh Zohāk in Azerbaidjan,” fig. 2).

Fig. 3. The oldest photograph of the Pavilion at Qal‘eh Zohāk taken in 1960 (after Mostafavi, “Yek asar-e tārikhi az dowrān-e Madhā tā ahd-e eslami. Qal’eh Zohāk dar Azarbāijān,” fig. 9).

Fig. 5. Qal‘eh Zohāk, the Pavilion in 2018 (photo: Max Damberger. https://www.maxblog.at).

Fig. 8. Qal‘eh Zohāk. Axonometric reconstruction of the Pavilion (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” fig. 4).

Fig. 9. Qal’eh Zohāk. The Pavilion and excavated remains (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” fig. 9/2).

Fig. 10. Qal’eh Zohāk. Plan and axonometric view of the the Hall (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” fig. 10).

Fig. 11. Qal’eh Zohāk. Reconstructed view of the Hall (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,”fig. 11/2).

Fig. 12. Qal’eh Zohāk. Derakhshi’s reconstructed view of the Hall (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” Asar, Nos. 38-39, 1984, p. 82, fig. 11/1).

Fig. 13. Qal’eh Zohāk. Plan of the building with a cruciform hall (after Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” Asar, Nos. 38-39, 1984, p. 84, fig. 13/1).

Archaeological Exploration:

Colonel William Monteith, British officer of the Indian Army is the first to have visited the ruins of Qal’eh Zohāk in 1810. Monteith gives a comprehensive description of the visible structures (Monteith, “Journal of a Tour Through Azerbaijan and the Shores of the Caspian,” pp. 4-5). He points out that the site was the object of later military actions and encampments. He finally identifies, quite rightly, the ruined fortress as a frontier town in Atropatene on the road from Parthia to Ganzak. Henry C. Rawlinson visited the ruins in the 1830s and did not agree with Monteith’s identification of the site as Parthian (Rawlinson, “Memoir on the Site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” p. 120, footnote).

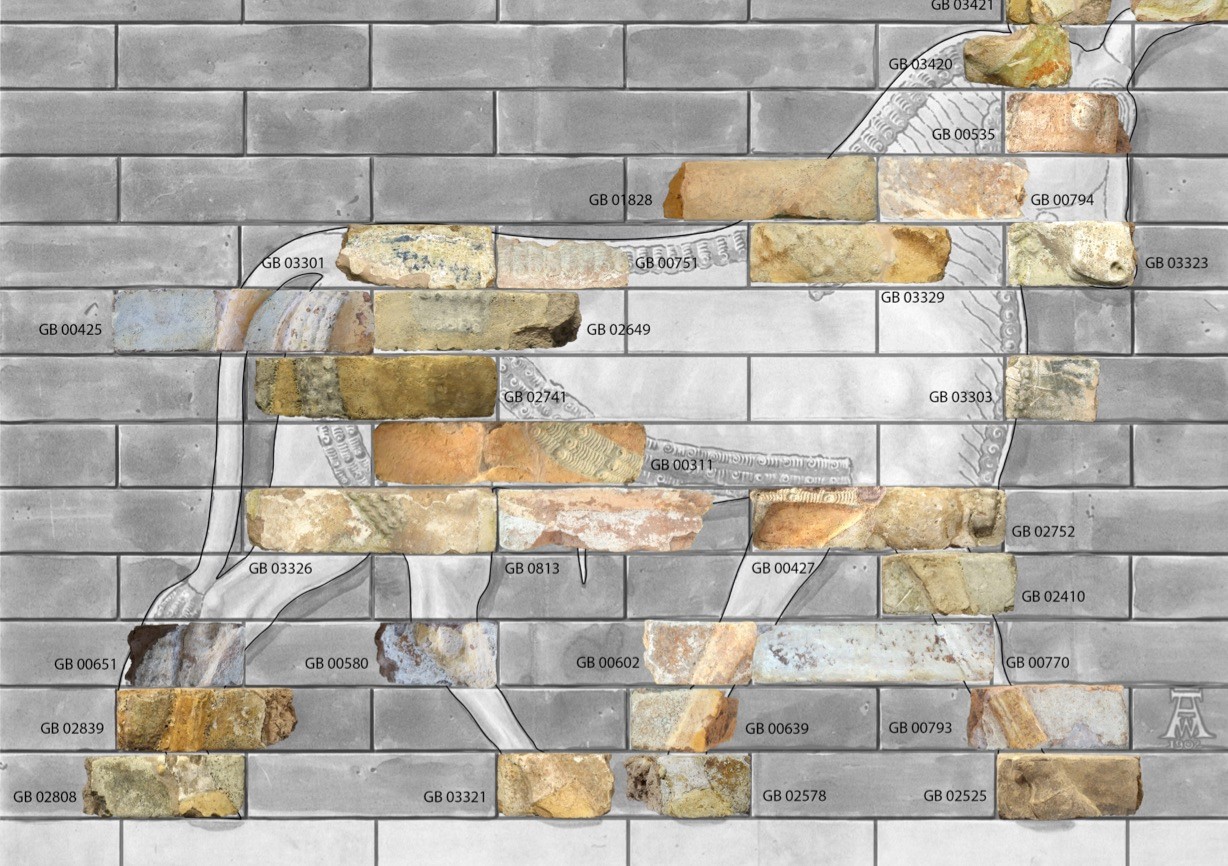

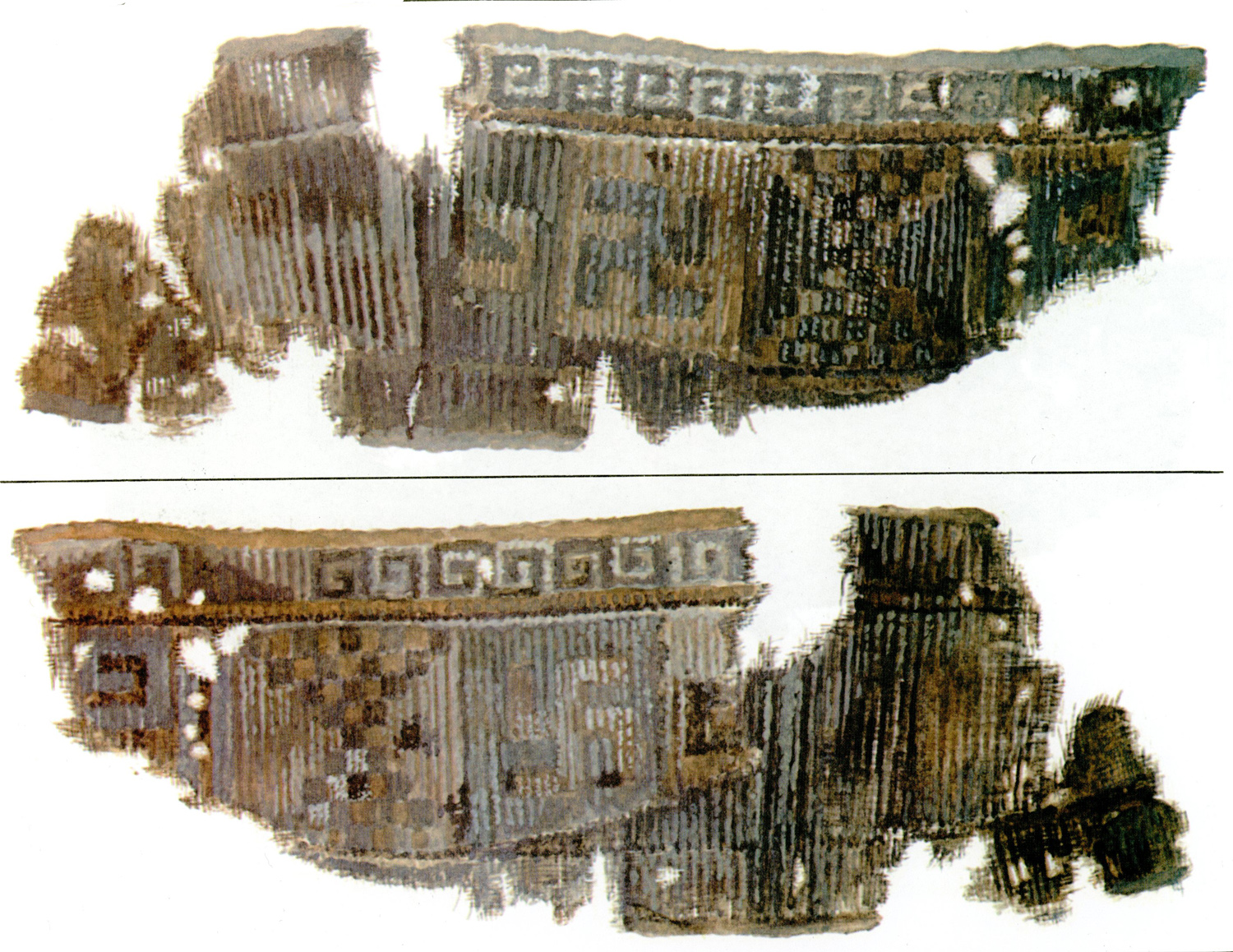

A preliminary visit by Klaus Schippmann in 1963 (Schippmann, “Archäologische Untersuchungen in Aserbaidschan im Jahre 1964,” p. 78; Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, pp. 369-376, figs 50-52) was followed by Wolfram Kleiss’ survey of the site (fig. 2). Kleiss published an accurate topographic plan of the fortress and its visible architectural remains with sketches of stucco fragments (fig.14, fig.15, fig.16) and reconstructions of the Pavilion (Kleiss, “Qal’eh Zohak in Azerbaidjan”). Later, Reinhardt Pohanka found similarities between the Qal’eh Zohak Pavilion and those in Commagene and Ephesus (Pohanka, “Zum Bautyp des Pavilions Qaleh Zohak,” p. 244, figs. 21-23).

The Iranian Center for Archaeological Research carried out excavations at the site, under the direction of Javad Qandgar, between 2000 and 2006 (Qandgar, “Kavosh-e Qaleh Azhdehāk,”; Qandgar, Esma‘ili, and Rahmatpour, “Kāvoshhāy-e bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtroud”; Derakhshi, “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,”; Derakhshi and Khademi, “The Chronological Occupation of Zahak Castle on the Basis of Three Seasons of Archaeological Excavations, 2000-2002,”), the full results of which are yet to be published.

Finds:

Stuccoes with the exceptional figure of a warrior, floral, animal, and geometrical motifs (fig.17, fig.18, fig.19, fig.20, fig.21, fig.22, fig.23).

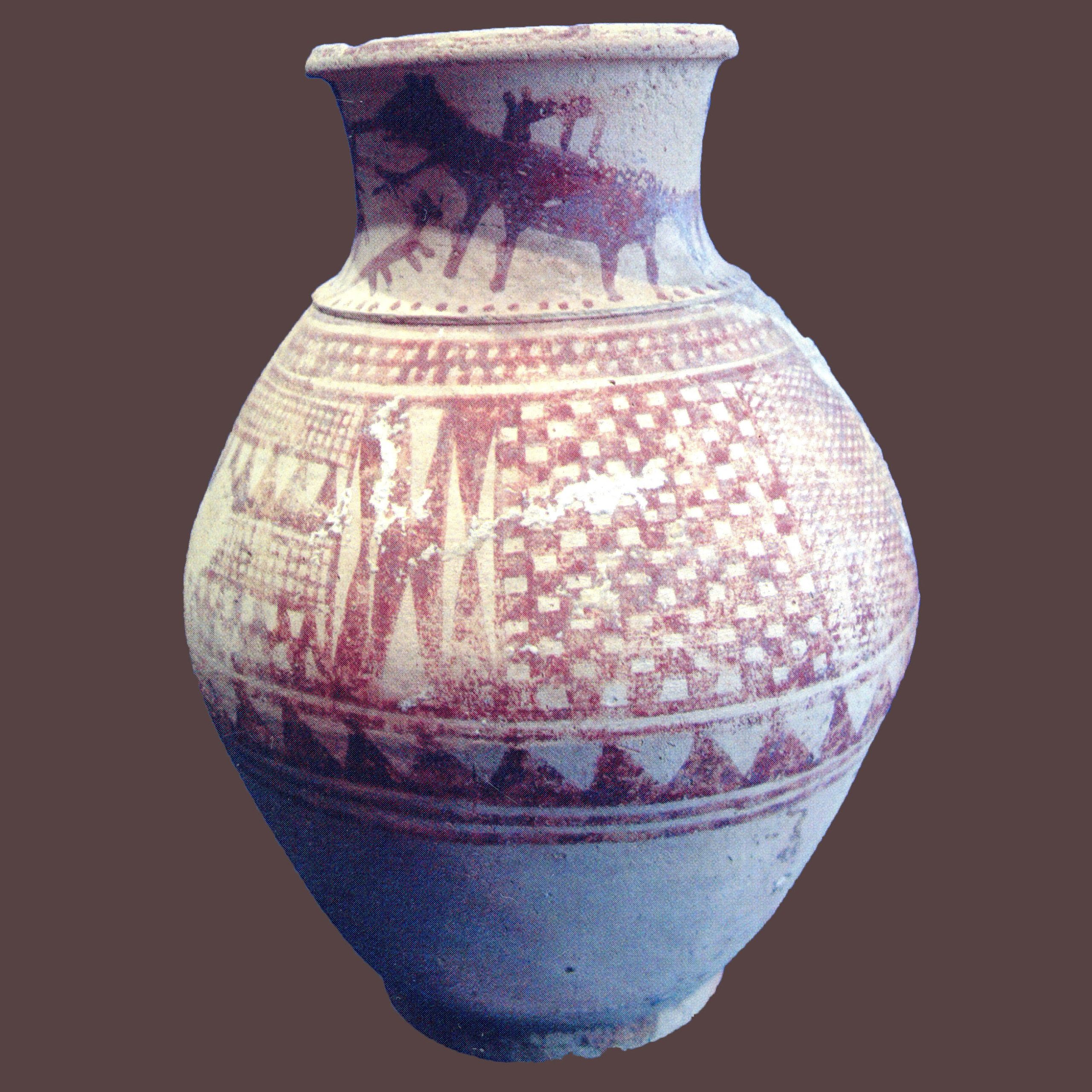

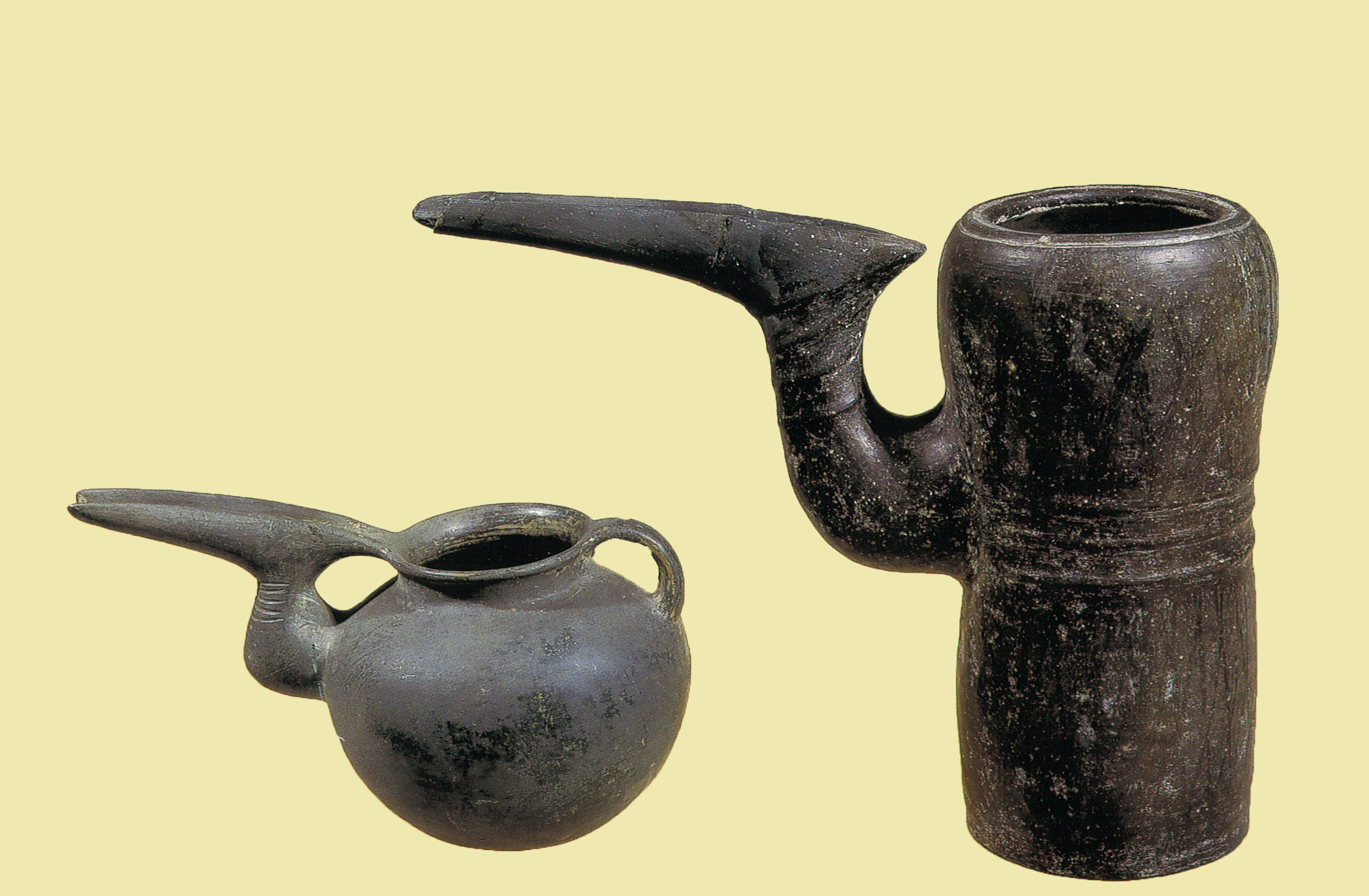

Pottery finds consist of the Triangle Ware and possibly Festoon Ware of the late Iron Age/Achaemenid period, the Clinky Ware of the Parthian period (Kleiss, “Qal’eh Zohak in Azerbaidjan,” pp. 183-184, figs. 21-22), and late Sasanian, early Islamic glazed ceramics.

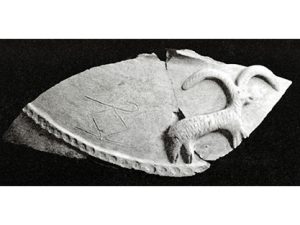

Figurative pottery with the relief figure of a mountain goat (fig.24).

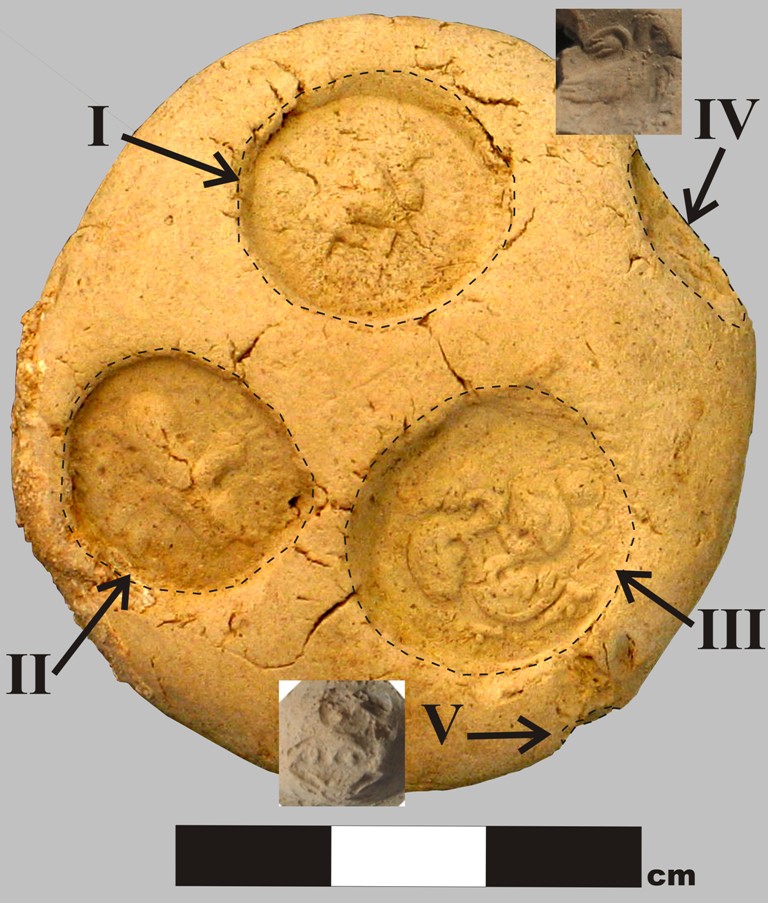

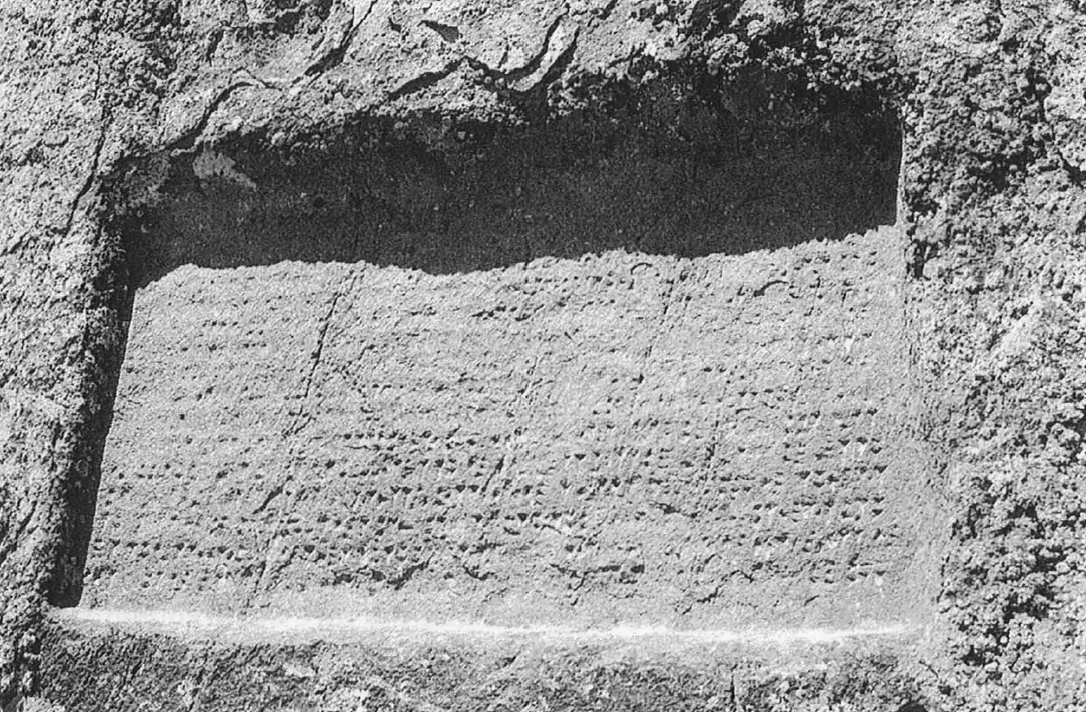

Ostracas: a few fragmented vessels bear Middle Persian texts (fig.25, fig.26).

Fig. 17. Qal’eh Zohāk. Stucco panel depicting an eagle hunting a bull

(photo: Fabien Danny, published under Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.5: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Zahhak_castle_stucco_1.JPG)

Fig. 18. Qal’eh Zohāk. Stucco panel depicting a warrior

(photo: Fabien Danny, published under Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.5: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

wiki/File:Zahhak_castle_stucco_2.JPG)

Fig. 19. Qal’eh Zohāk. Part of a column capital decorated with polychrome motifs (photo: Hasan Derakhshi).

Fig. 20. Qal’eh Zohāk. Stucco panel with framed circles (photo: Hasan Derakhshi)

Fig. 21. Qal’eh Zohāk. Stucco fragment of a merlon (photo: Hasan Derakhshi).

Fig. 22. Qal’eh Zohāk. A column capital decorated with Ionian volutes and floral motifs (photo: Hasan Derakhshi).

Fig. 23. Qal’eh Zohāk. Stucco decorated panels with human portraits (photo: Hasan Derakhshi).

24. Qal’eh Zohāk. A potsherd with the relief figure of a mountain goat (after Qandgar, Esma‘ili, and Rahmatpour, “Kāvoshhā-ye bāstanshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtrūd, ”, p. 216).

Fig. 25. Qal’eh Zohāk. Ostraca with Middle Persian text (after Qandgar, Esma‘ili, and Rahmatpour, “Kāvoshhā-ye bāstanshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtrūd, ” p. 216).

Fig. 26. Qal’eh Zohāk. Ostraca with Middle Persian text (after Qandgar, Esma‘ili, and Rahmatpour, “Kāvoshhā-ye bāstanshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtrūd, ” p. 216)

Bibliography:

Derakhshi, H., “Bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Zohāk,” Asar, Nos. 38-39, 1384 H.S./2005, pp. 61-74.

Derakhshi, H. and F. Khademi, “The Chronological Occupation of Zahak Castle on the Basis of Three Seasons of Archaeological Excavations (2000-2002),” Bulletin of Parthian and Mixed Oriental Studies, vol. 1, 2005 (2006), pp. 31-42.

Kleiss, W., “Qal’eh Zohak in Azerbaidjan,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 6, 1973, pp. 163-188, pls. 41-43.

Minorsky, V., “Roman and Byzantine Campaigns in Atropatene,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 11, No. 2, 1944, pp. 243-265.

Monteith, W., “Journal of a Tour Through Azerbaijan and the Shores of the Caspian,” The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 3, 1833, pp. 1-58.

Mostafavi, M. T., “Yek asar-e tārikhi az dowrān-e Mādhā tā ahd-e eslāmi. Qal’eh Zohak dar Azarbāijān,” Yād-Nāme-ye Irani-ye Minorsky, I. Asfhar and M. Minovi (eds.), Tehran, 1348 H.S./1969, pp. 128-144.

Pohanka, R., “Zum Bautyp des Pavilions Qaleh Zohak, Nordost Azerbeidschan, Iran,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 16, 1983, pp. 237-254.

Qandgar, J., “Gozāresh-e Qal’eh Azhdehāk, shahrestān-e Hashtrūd, Azarbaijān-e sharqi,” Proceedings of the Second National Congress of Iranian Studies, Tehran, 2004, pp. 428-480. Qandgar, J., Esma‘ili, H., and Rahmatpour, M., “Kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenāsi-ye Qal’eh Azhdehāk, Hashtrūd, ” Proceedings of International Symposium on Iranian Archaeology, Northwest Region, 2003, M. Azarnoush (ed.), the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, Tehran, 2005, pp. 193–228.

Rawlinson, H. C., “Memoir on the Site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 10, 1840, pp. 65-158.

Schippmann, K., “Archäologische Untersuchungen in Aserbaidschan im Jahre 1964,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 7, 1967, pp. 77-81.

Schippmann, K., Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, Berlin, 1971.