Qal’eh Gabri / Qal’eh Irajقلعه گبری / قلعه ایرج

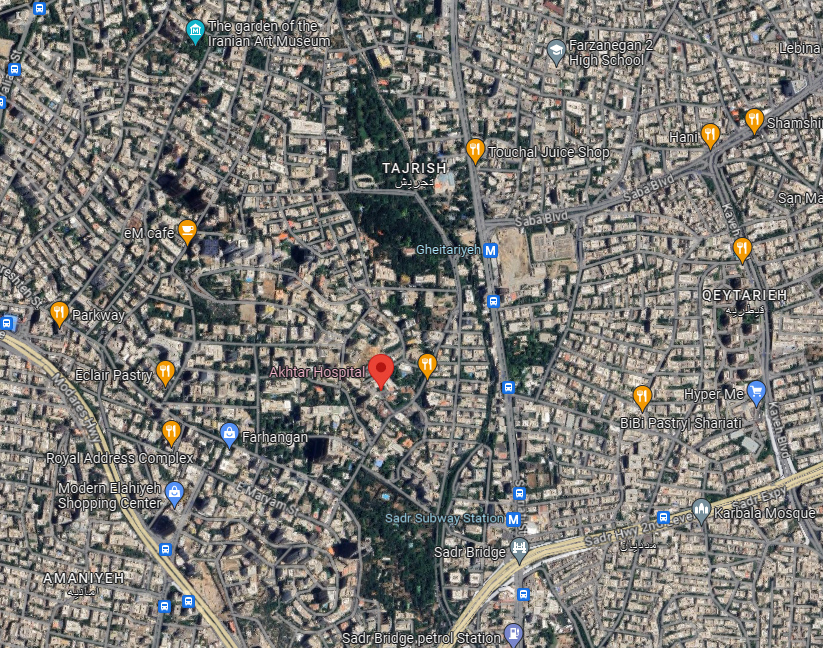

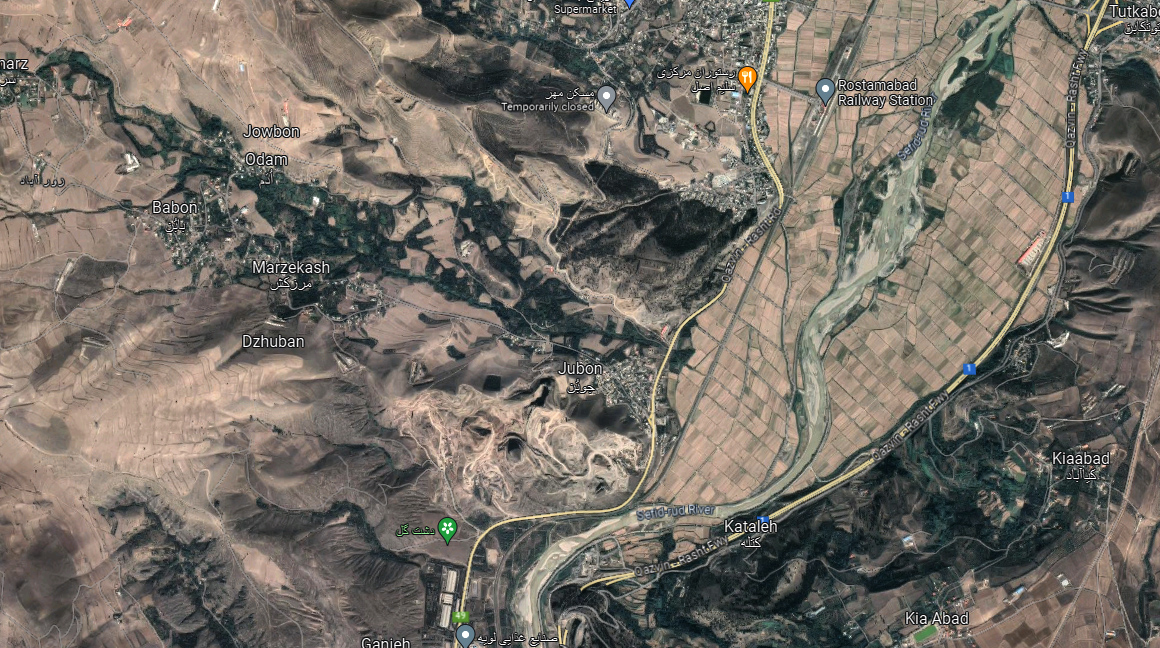

Location: Qal’eh Gabri or Qal’eh Iraj is located southeast of Tehran, in central northern Iran, Tehran Province.

35°20’33.4″N 51°40’46.7″E

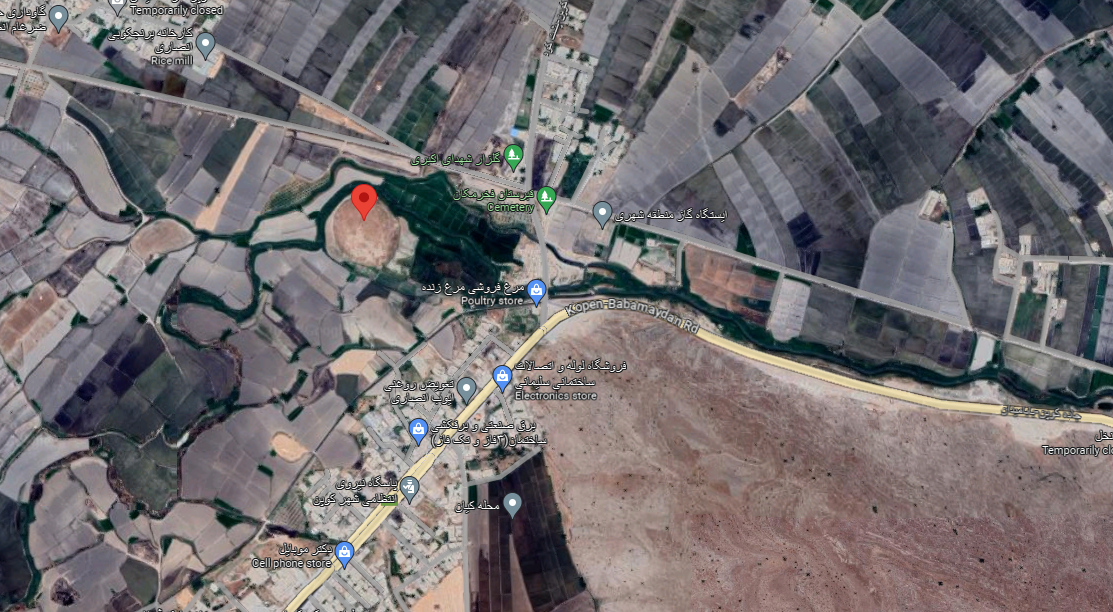

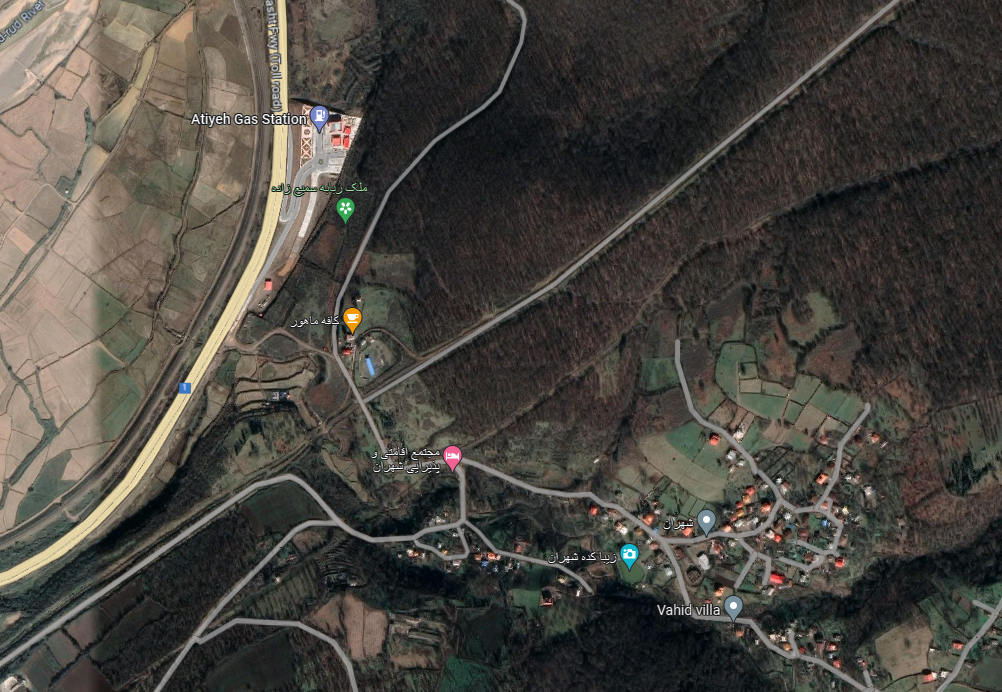

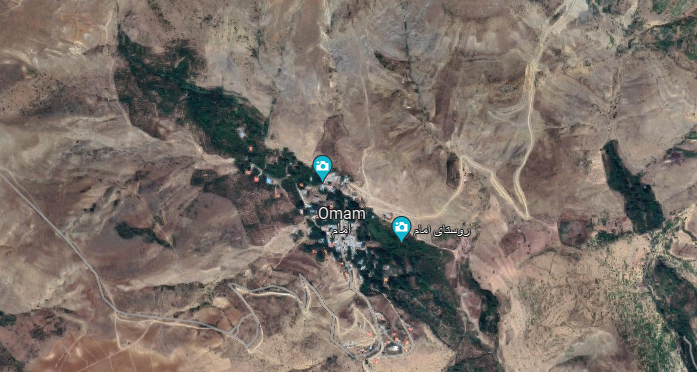

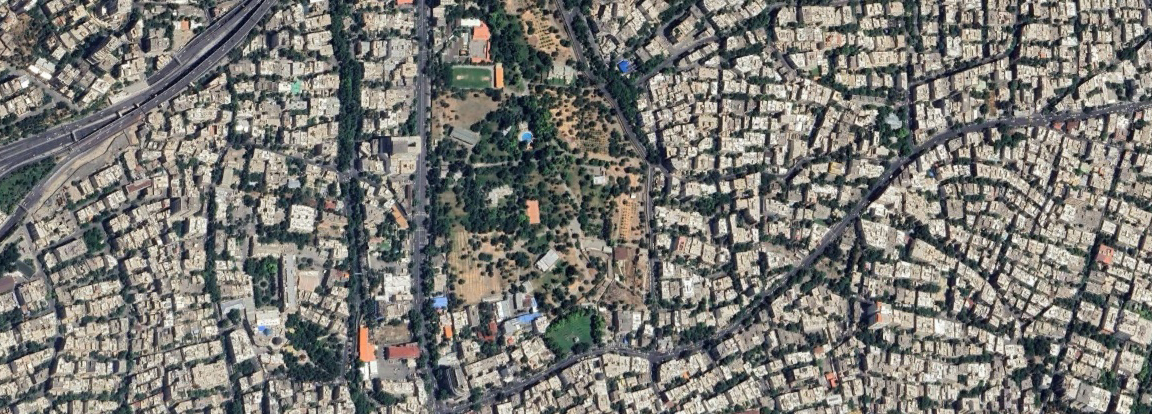

Map

Historical Period

Parthian, Sasanian, Islamic

The large fortress of Qal’eh Gabri or Qal’eh Iraj – as it is called today –, located 4 kilometers northeast of Varāmin and 55 km southeast of Tehran. Qal’eh Gabri was not isolated; it served as the southern stronghold of the city wall of medieval Rey. The city’s fortification has a triangular shape, stretching from around the Rashkan Fortress near Mount Bibi Shahrbānū southward until it reaches Qal’eh Gabri. From there, it extends in an irregular line toward the northwest until it reaches another fortress similar to Qal’eh Gabri, and from there it continues eastward until it reconnects with the Rashkan Fortress. The complex lies at a strategic intersection of major routes: from Mazandaran through Qom to central and southwestern Iran, and along east-west corridors connecting Khorasan to Azerbaijan, western Iran, and onward to Baghdad. The name Qal’eh Gabri, meaning “Castle of the Infidels” or “Castle of the Zoroastrians,” suggests that the local Muslim population believed the structure predated the Islamic conquest of the region in the seventh century. The name Qal’eh Iraj first appears in 19th-century sources (see below). It remains uncertain whether this designation refers to a landowner or preserves an earlier, possibly ancient, toponym.

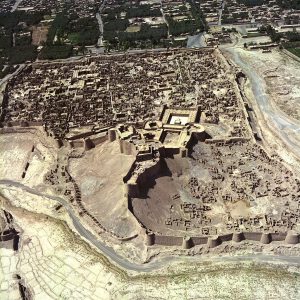

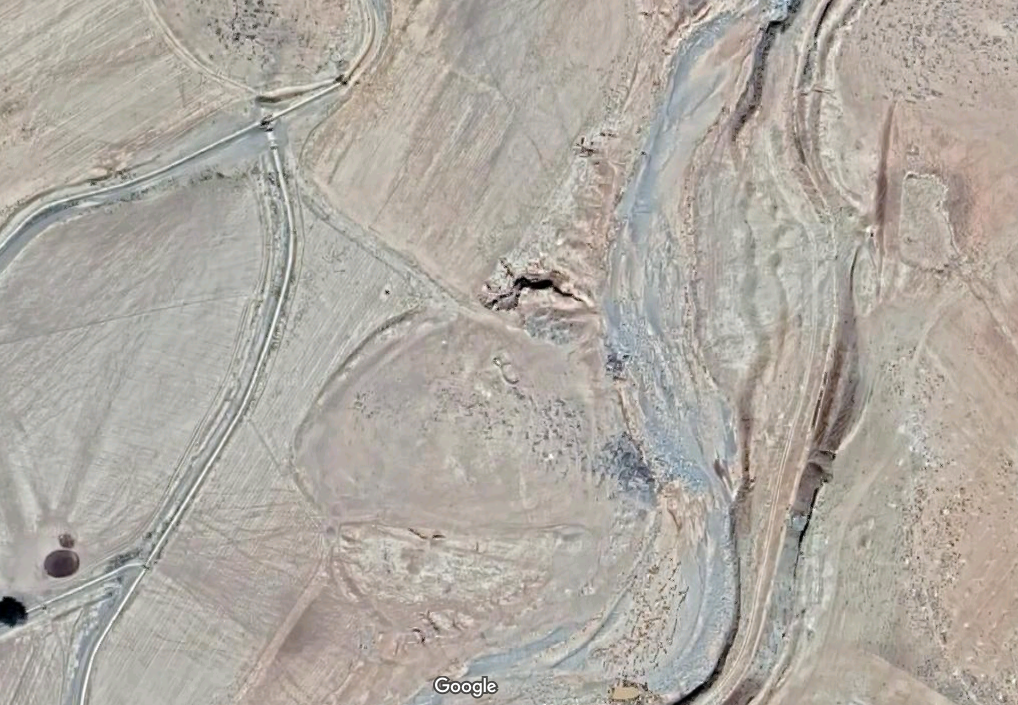

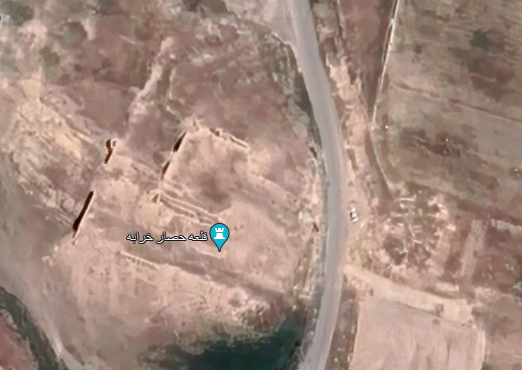

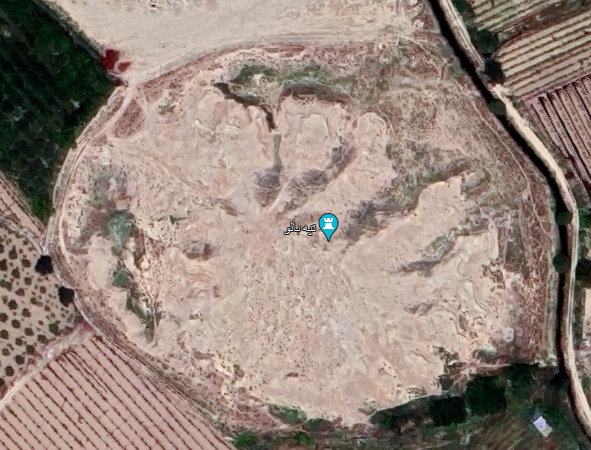

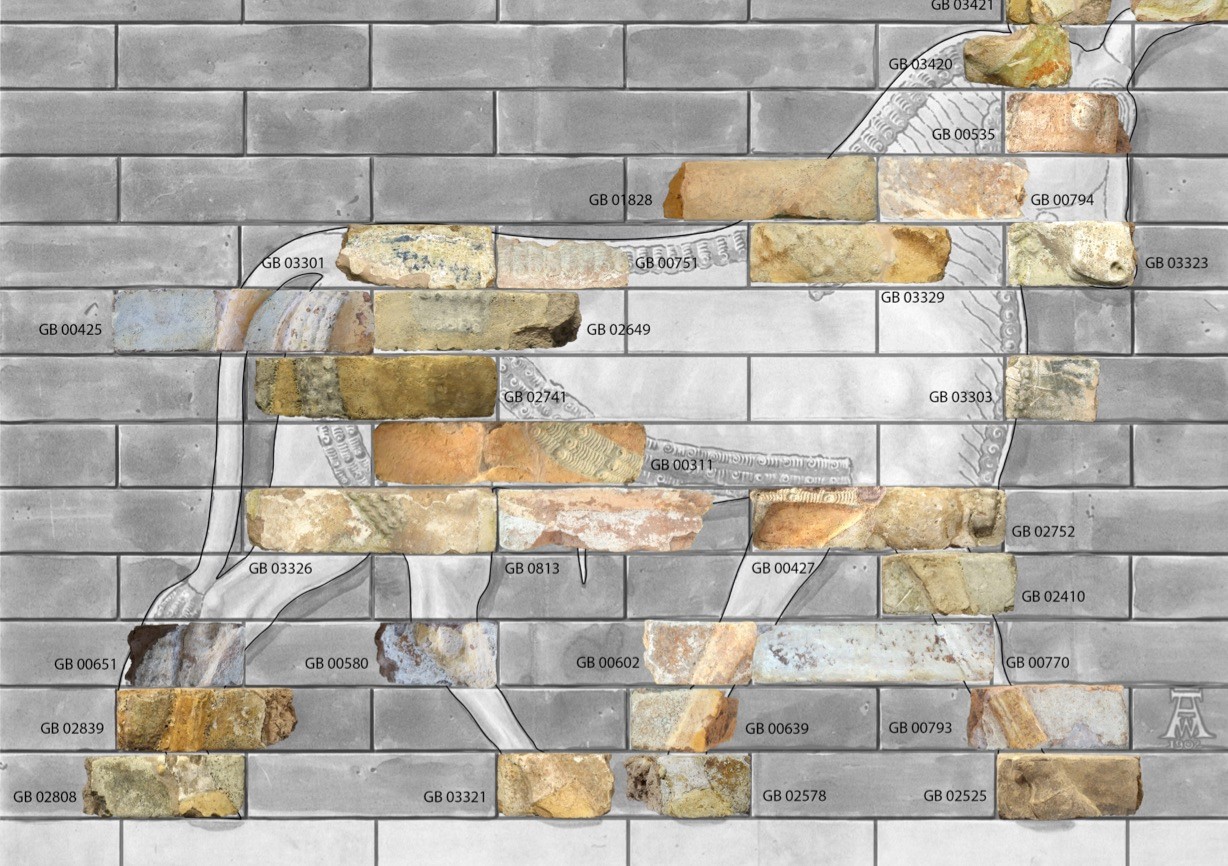

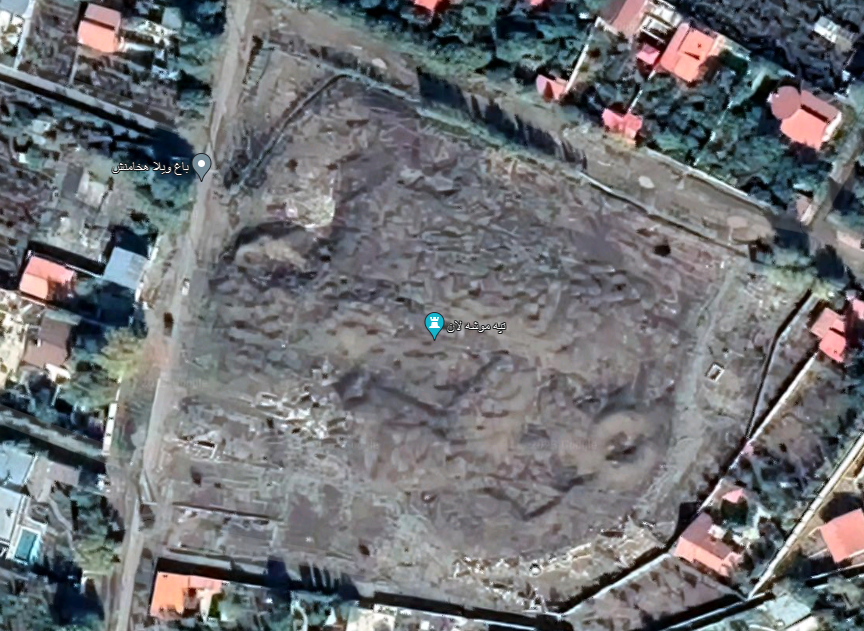

Qal’eh Gabri is a roughly square mud-brick fort covering an area of 187 hectares (fig. 1). Its interior measures approximately 1,214 m. from north to south and 1,150 m. from east to west, giving the complex a slightly elongated north-south rectangular shape, further emphasized by an original gate located in the southern façade. According to a recent estimate, Qal’eh Gabri encompasses more than twice the combined area of all forts along the Gorgan Wall. The fortress spans six times the total area of all forts on Hadrian’s Wall, more than double that of any single Roman fortress, and exceeds the size of any late Roman non-urban military base by more than tenfold—surpassing its Roman counterparts in both ambition and scale.

The southern side of the fort is equipped with 42 towers, including the two corner towers and the towers flanking the main gate. The northern wall, based on the fort’s current state of preservation, appears to have no gate and is reinforced by 34 towers, including its corner towers. Both the eastern and western sides are lined with 36 towers each, including two corner towers and two gate towers per side. The gates on the east and west sides were later additions, likely constructed during major renovations or expansions after the seventh century. There is a dry moat 30 m. wide and 4 m. deep near the western wall, reinforcing that side of the fortress.

The interior of the complex shows no signs of construction apart from a low mound about 60 m. in diameter and 2 m. in height, and two areas of brick debris. These brick debris areas may be the remains of buildings or places where bricks were produced. Fired bricks measuring 31 x 32 x 6 cm have been found there, which may date from pre-Islamic to early Islamic times.

The original design of the south façade suggests that the structure was not purely a military fortification, but also fulfilled a representative function, even into the second phase. Wolfram Kleiss believes that the presence of round arches, together with the use of large mud-bricks, points to a pre-Islamic construction period for Qal’eh Gabri, most likely dating to the Parthian rather than the Sasanian period. Qal’eh Gabri may have functioned as a heavily fortified military camp situated along the important east-west trade route, while also serving certain ceremonial or representative purposes associated with the royal court. In the late Sasanian/early Islamic period, it is possible that gates to the east and west were added, perhaps in conjunction with the abandonment of the original south gate. In the seventh century, Qal’eh Gabri appears to have remained in use and was likely only finally abandoned during the Mongol invasion, in favor of nearby Varāmin, which quickly grew into an important trading center.

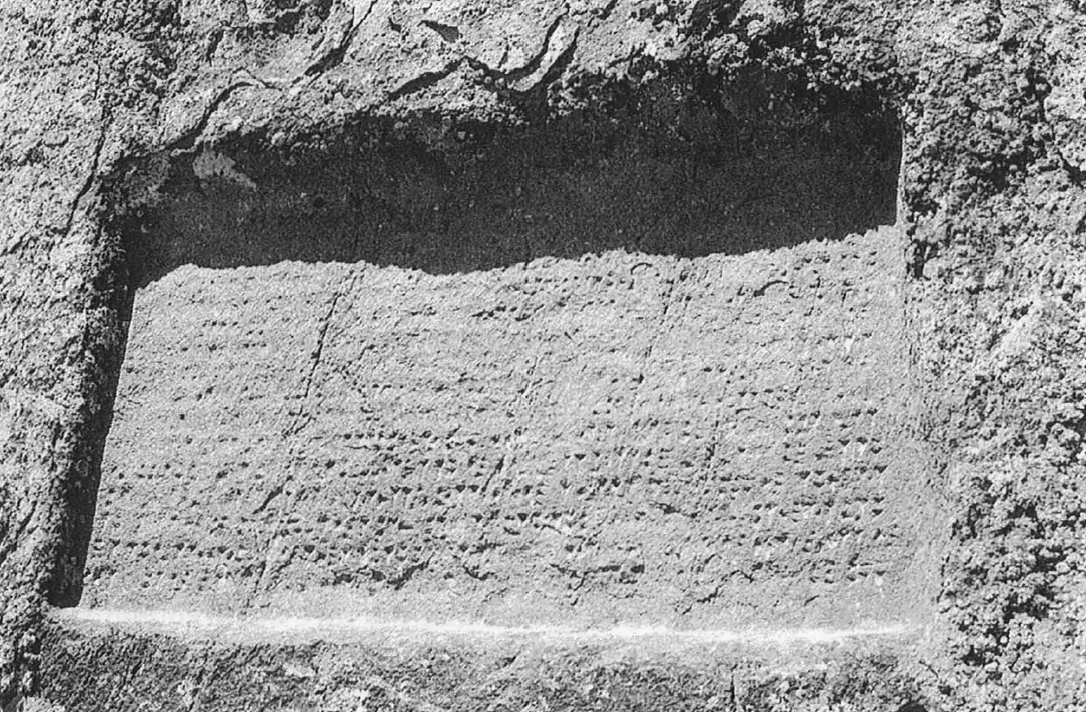

Textual evidence from the limited excavations indicates that the currency used in the transactions recorded on the Qal’eh Iraj ostraca was the drahm. Such commodities are consistent with the context of a military base, though this is not the only plausible interpretation. The reference to a darig suggests the presence of some form of administrative structure, further supporting the view that the site functioned as a Sasanian military fortress. Given the current state of evidence, the ostraca are most plausibly dated to the sixth or seventh century, although an earlier date cannot be definitively ruled out.

Archaeological Exploration

The extent of ancient and medieval Rey has long captivated Western scholars, with serious academic interest dating back to the early nineteenth century. Among the earliest and most influential figures was Robert Ker Porter—British traveler, writer, and artist—who provided the first comprehensive description of the city’s ruins. Ker Porter also produced the earliest known topographic map detailing the layout of the medieval city’s structures and defensive walls (fig. 2).

While writing on the toponyms in connection with ancient Ecbatana, Henry C. Rawlinson concluded that the ancient Rey “was at Kal’eh Erig” (Iraj), near Varamin, and “must not be confounded with the Arabian Reï.”

The first substantial description of the site was given by Edward Backhouse Eastwick, a British Orientalist and diplomat, who visited the ruined fort in 1860 and wrote:

At 2.30 p.m. we rode across country to see the celebrated ruin called Kalah i Iraj, alias Europus, alias Rhages, in its second stage of existence, when it had migrated to the edge of the salt desert. The word Rhages is probably derived from Iraj. The ruin lies two miles south-west of Jafarabad. The walls are of mud, perhaps fifty feet high, and very thick. The interior is a parallelogram 1,800 yards long by 1,500 yards broad. In it were patches of wheat six inches high, and out of one of them our greyhounds started a hare, of a silver-gray colour.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, Mohammad-Hasan Khan Etemad al-Saltana, a prominent Iranian minister, writer, and politician of the Qajar era, gave one of the most insightful interpretations of the fort’s strategic significance as an integral part of the ancient city of Rey:

According to the claim of some scholars, Raghas or Reyy is the same as Qal’eh Iraj, which is located near the city of Varāmin. However, it is highly probable that the city of Reyy covered the region and lands in the southeastern part of the capital, Tehran, with the sacred shrine of Abd al-Azim being part of that area. Since the plain of Reyy extends as far as Varāmin, Qal’eh Iraj is situated at the eastern end of this plain and, at that time, was considered a significant military fortress. The Kianid kings built it to protect the kingdom and defend it against the attacks and incursions of Turanian tribes, stationing troops and a garrison there. And because it was built in the plain of Reyy and not very far from the city of Reyy, it is possible that it was also called the Castle of Raghas.

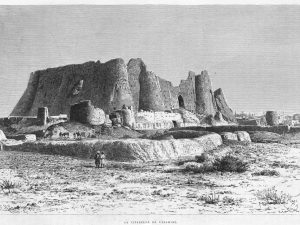

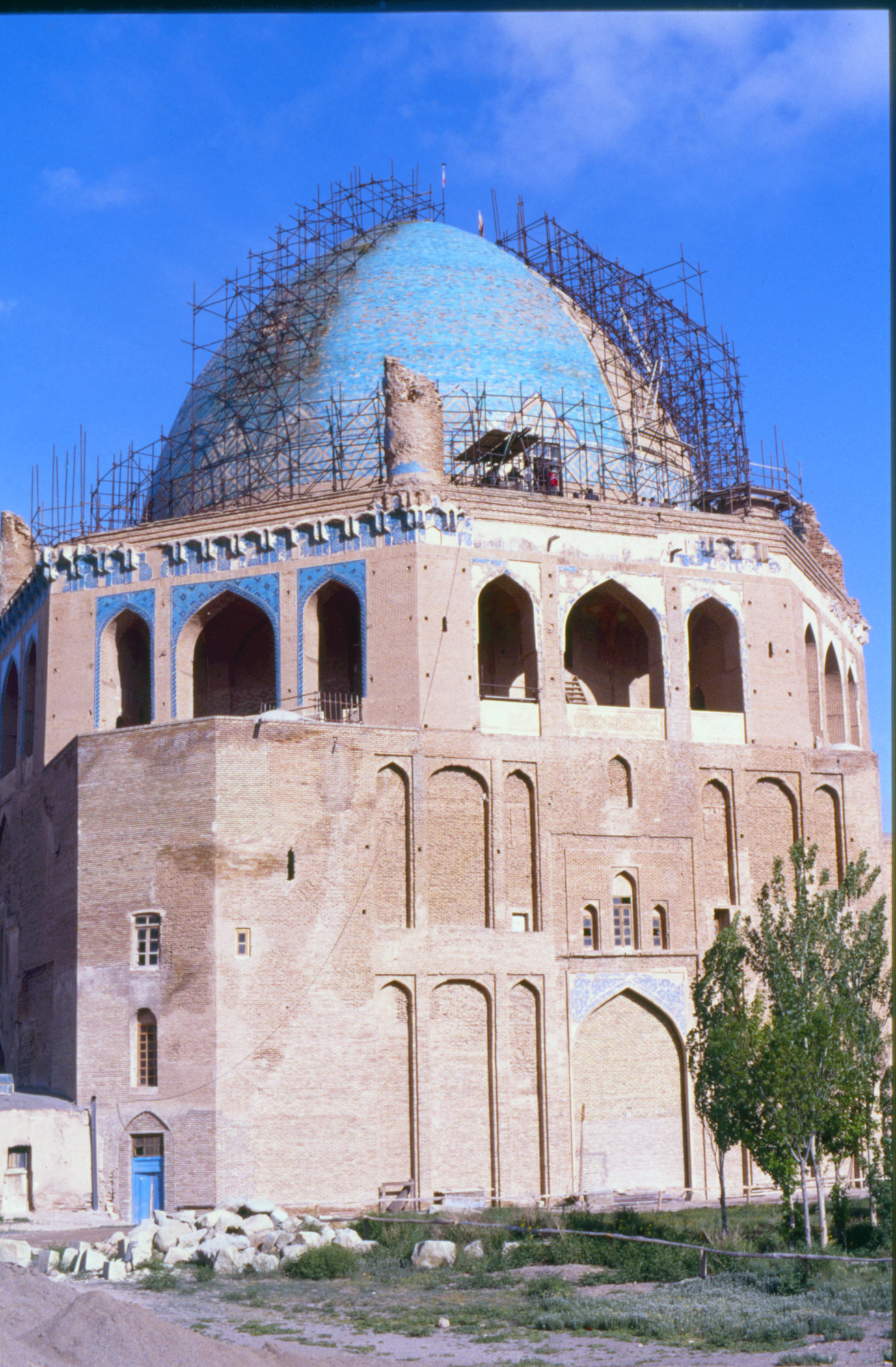

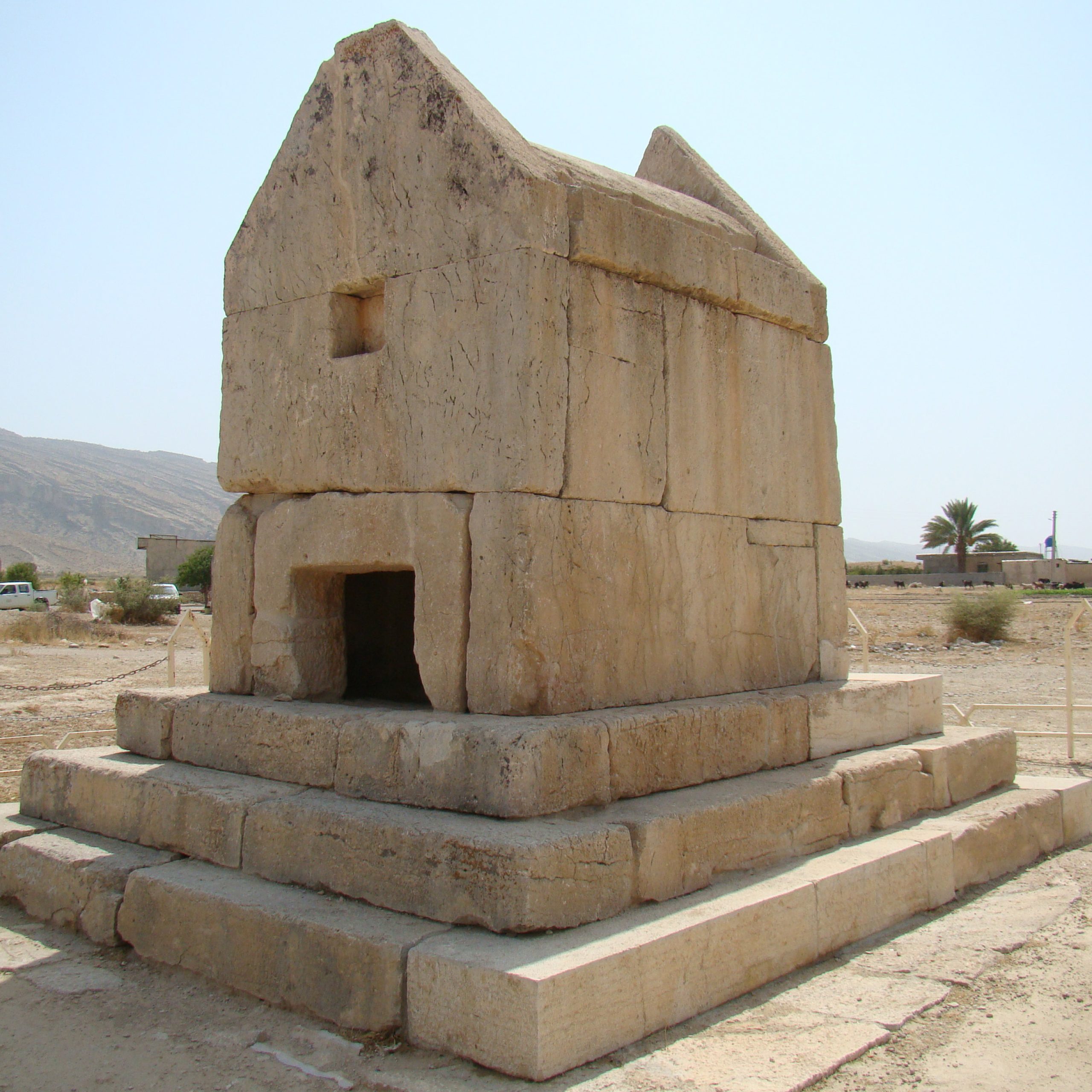

In 1884, Marcel and Jane Dieulafoy visited the ruined fort and published an engraving depicting its main section, which remained in remarkably impressive condition (fig. 3). This was followed by a brief account from George N. Curzon, who described the fort as a monument of “remote antiquity.”

Drawing on Etemad al-Saltana’s writings, Hossein Kariman gave only a brief mention of Qal’eh Gabri in his seminal work on Reyy, situating the fort within the broader network of the city’s ancient defensive structures.

The first comprehensive archaeological study of the monument was conducted by Wolfram Kleiss in the 1970s and 1980s, on behalf of the Tehran branch of the German Archaeological Institute. In 1991, Yahya Kowsari briefly excavated Qal’eh Gabri under the auspices of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research.

The Tehran branch of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization undertook a series of surveys and restoration work in the plains of Rey and Varāmin. In 2001, Mohammad-Reza Khalatbari drafted a report on the site’s condition. In 2002, further work was undertaken through the Qaleh Iraj Documentation Project by Afshin Farzin. The resulting report documented the site’s surface materials and included illustrations of the standing fortification walls.

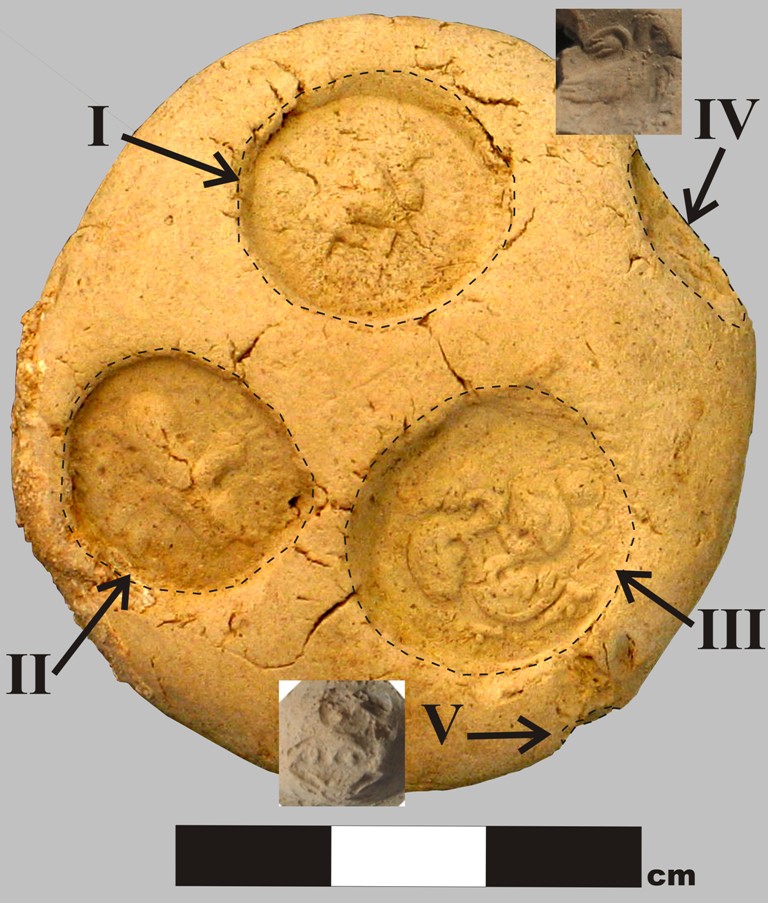

Between 2008 and 2015, on behalf of the Tehran branch of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization conducted excavations at Qal’eh Gabri. These excavations resulted in the discovery of a number of significant archaeological features as well as a collection of seals, seal impression, and ostraca.

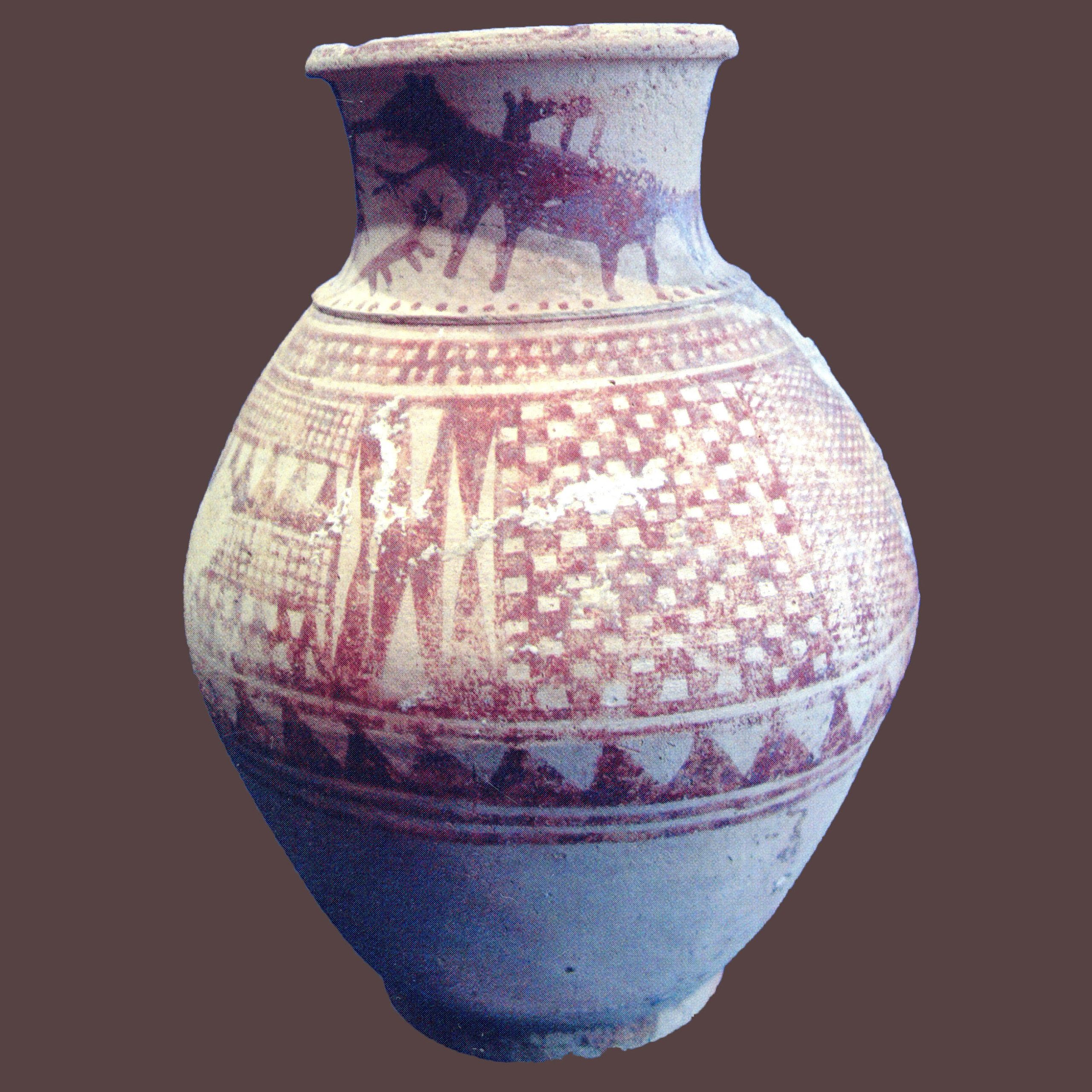

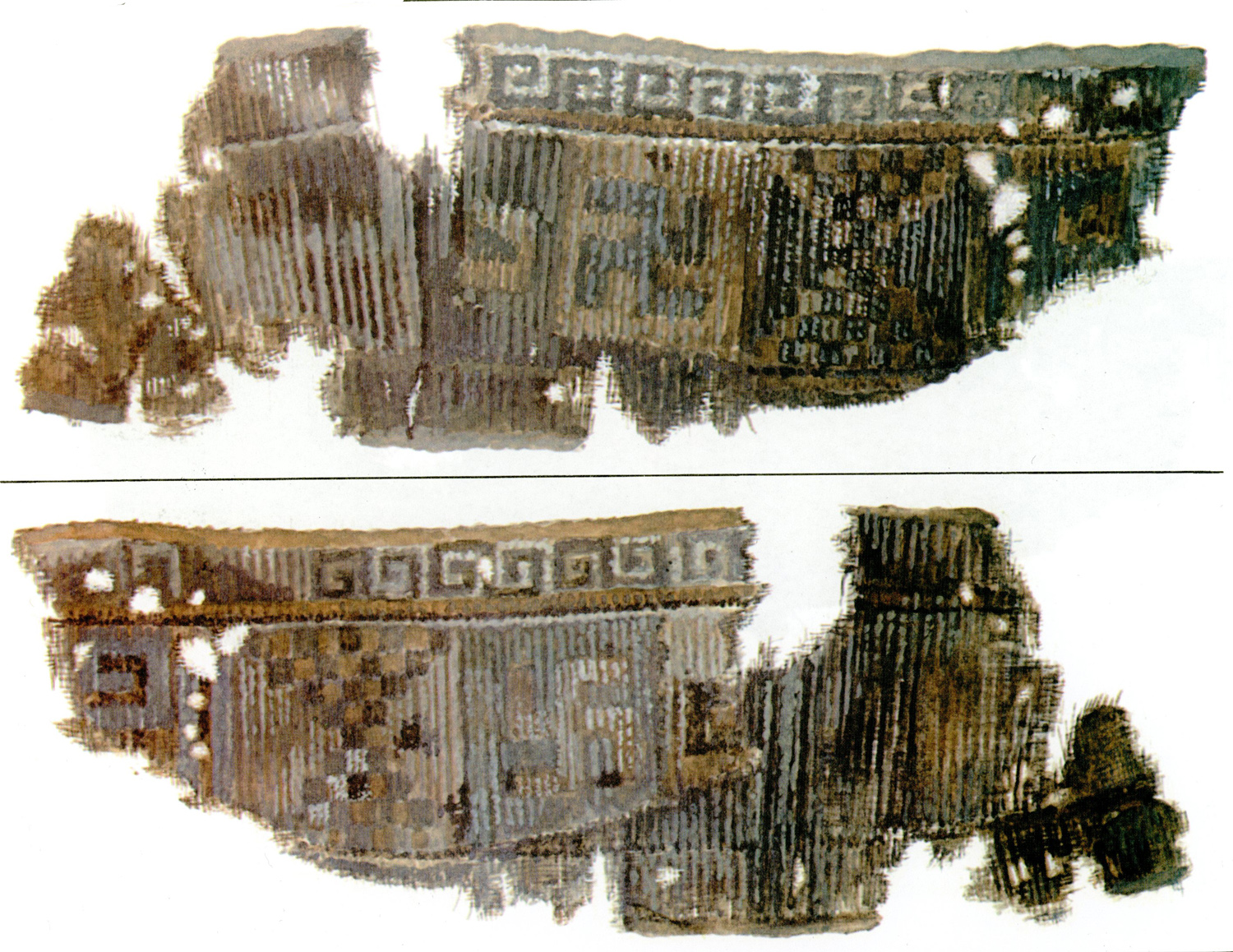

Finds

Excavated finds consists of potsherds of Sasanian and Islamic period; typical stamped Sasanian ceramics, plain and glazed ceramics of the 10th to 11th centuries; seal impressions, seals, ostraca.

Bibliography

Cereti, C., “Ostraca and bullae from Qal’eh Iraj,” in Ancient Arms Race. Antiquity’s Largest Fortresses and Sasanian Military Networks of Northern Iran, edited by E. W Sauer, J. Nokandeh and H.Omrani Rekavandi, vol. 2, Oxford and Philadelphia, 2022, pp. 461-472.

Curzon, G, N., Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 1, London, 1892, pp. 352-353.

Dieulafoy, J., La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane: Relation de voyage, Paris, 1887, pp. 142-145.

Eastwick, E. B., Journal Of A Diplomate’s Three Years’ Residence In Persia, vol.1, London, 1864, p. 285.

Etemad al-Saltana, M. H., Dorrar al-tījān fī taʾrīkh-e banī Ashkān, vol. 2, Tehran, 1308 H./1891, pp. 24-25.

Kariman, H., Rey-e Bāstān, vol. 1, Tehran, 1345/1966, pp. 24-25.

Ker Porter, R., Travels, vol. 1, London, 1821, pp. 357-364.

Kleiss, W., “Qal‘eh Gabri bei Veramin,” ArchaeologischeMitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 20, 1987, pp. 289-307, pls. 30–35.1.

Kowsari, Y., “Pazhuheshi dar Qal’eh Gabri, Rey-e bāstān,” Proceedings of the Congress on the History of Architecture and Urbanism in Iran, edited by B. A. Shirazi, vol. 3, Tehran, 1375/1996, pp. 453-494.

Mousavinia, M., M. Nemati, and E. W. Sauer, “Qal’eh Iraj: A Campaign Base/Command Centre of the Army’s Northern Division?,” in Ancient Arms Race. Antiquity’s Largest Fortresses and Sasanian Military Networks of Northern Iran, edited by E. W Sauer, J. Nokandeh and H.Omrani Rekavandi, vol. 1, Oxford and Philadelphia, 2022, pp. 358-385.

Nemati, M., Mousavinia, M., Sauer, E., and Cereti, C, “Largest Ancient Fortress of South-West Asia and the Western World? Recent Fieldwork at Sasanian Qaleh Iraj at Pishva, Iran,” Iran, vol. 58, pp. 1-31.

Rawlinson, H. C., “Memoir on the Site of the Atropatenian Ecbatana,” The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London, vol. 10, 1840, p. 138.