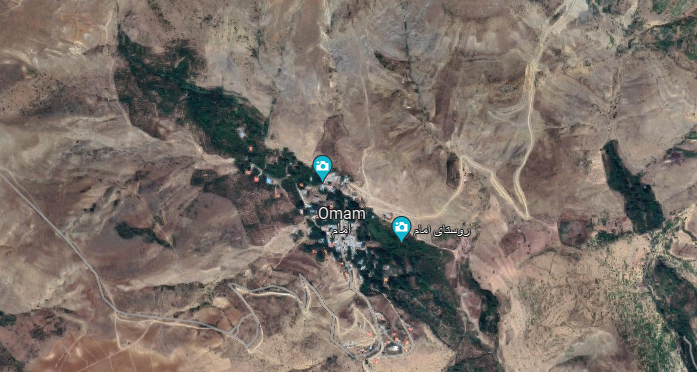

Qalāichi / Segerdān / Qal’eh Haidar Khanقلایچی / سه گردان / قلعه حیدرخان

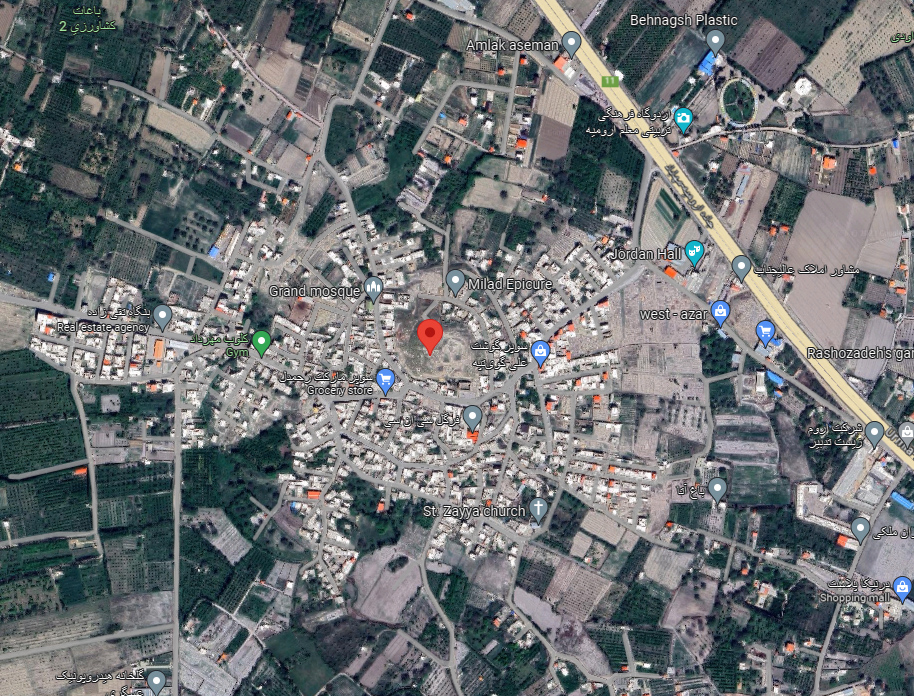

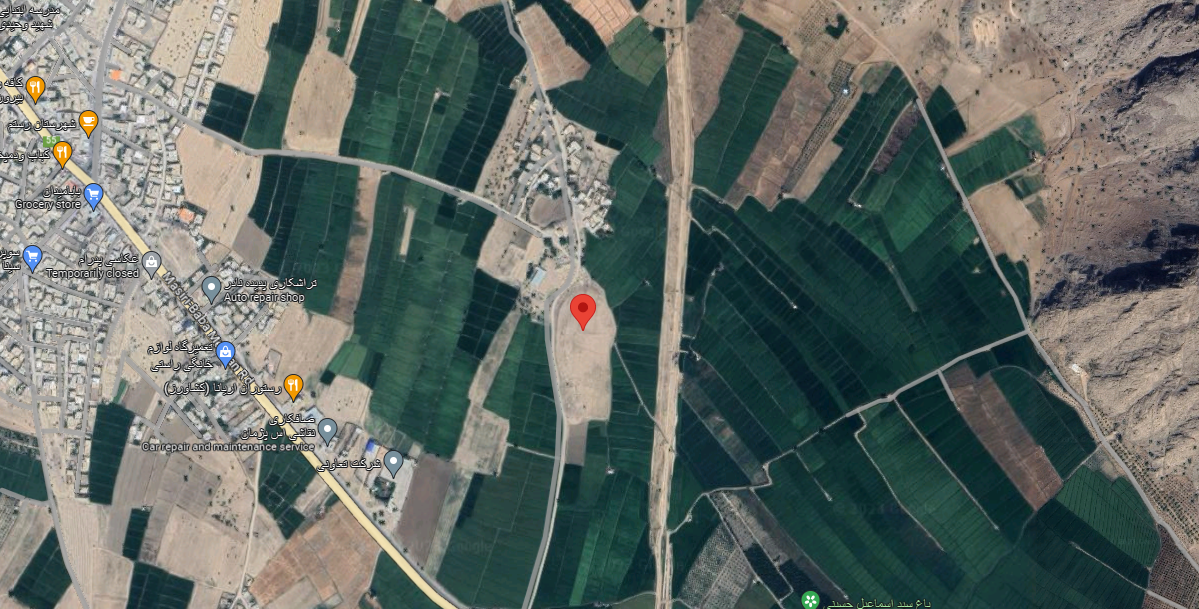

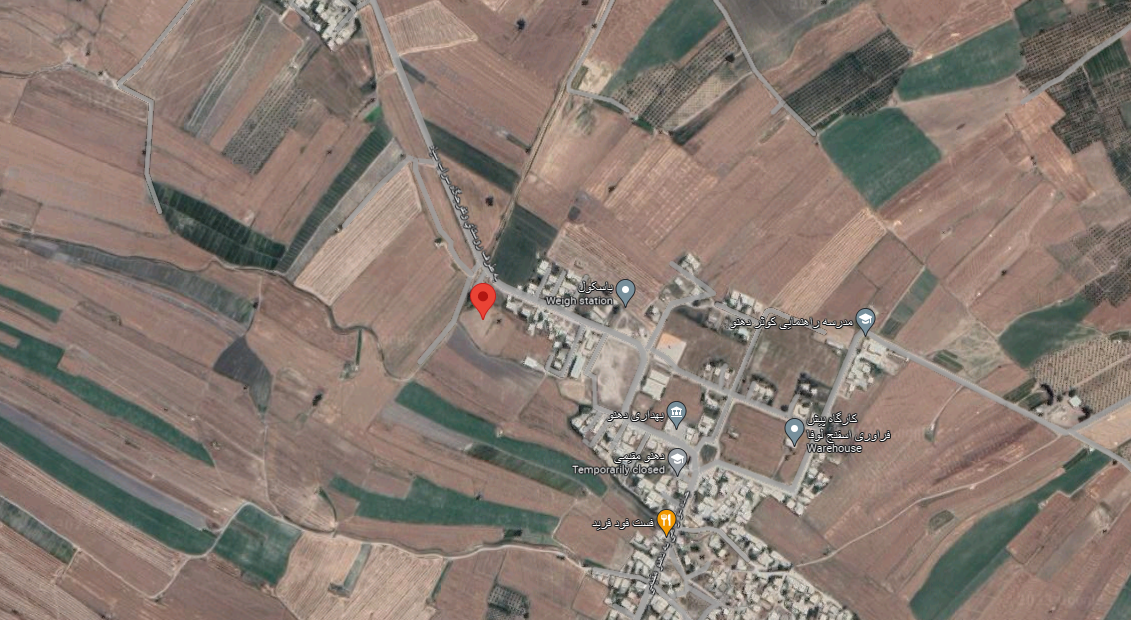

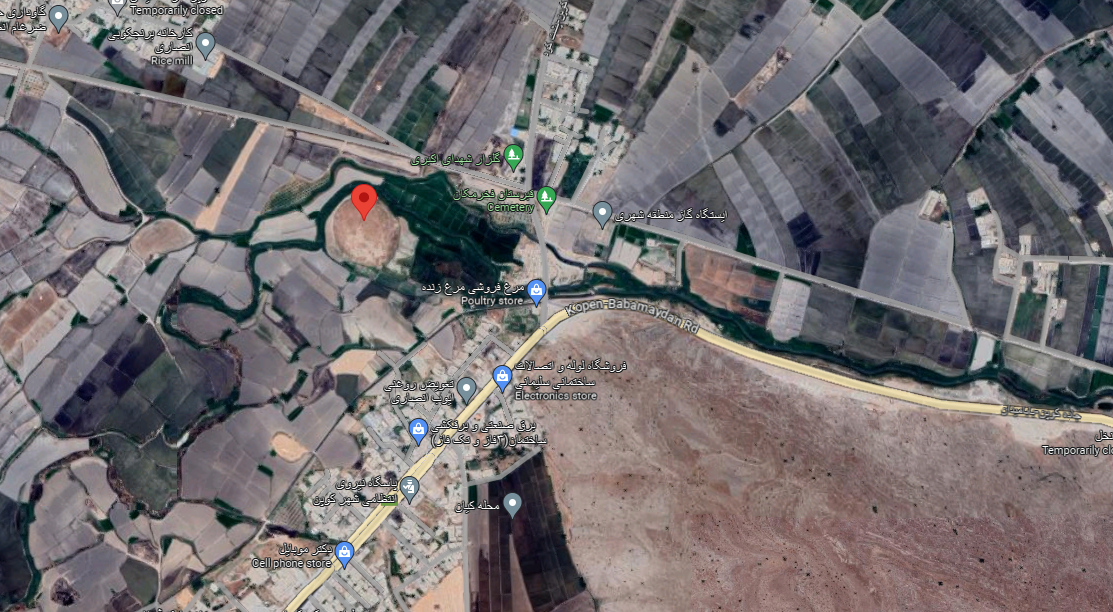

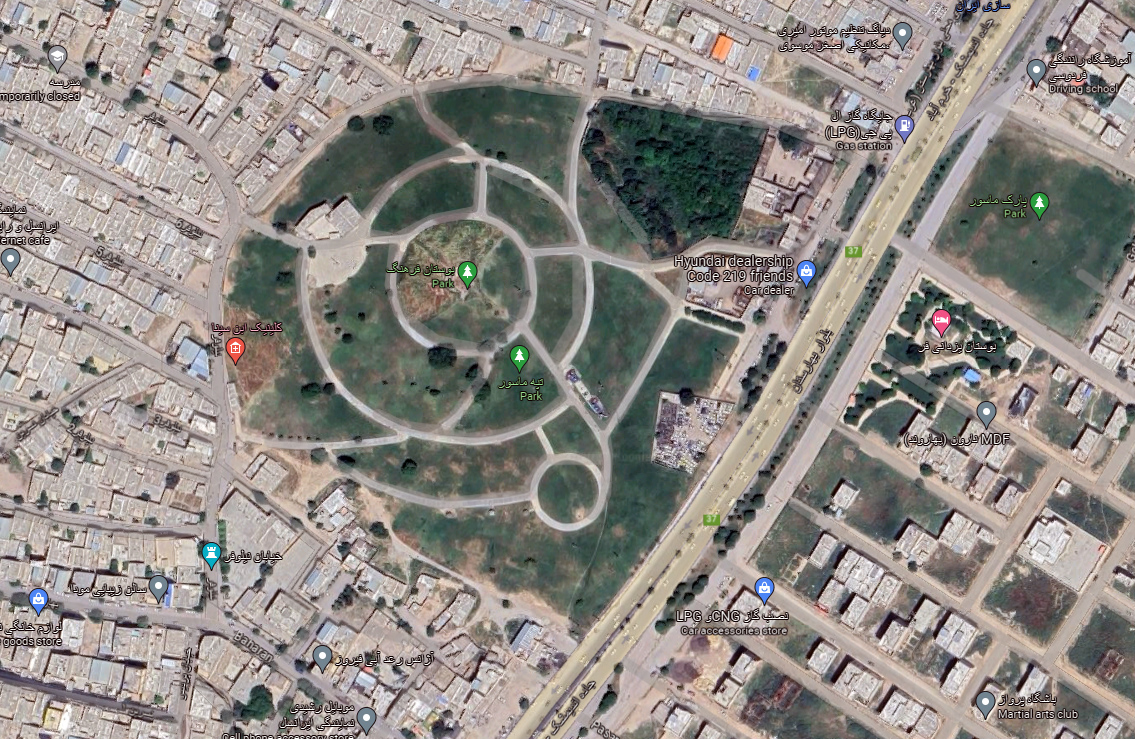

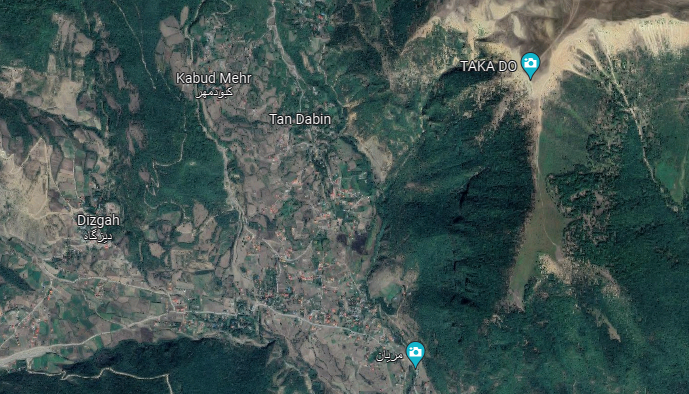

Location: Qalāichi is located 7 km northeast of Bukan, in northwestern Iran, West Azarbaijan Province.

36°34’15.94″N 46°16’29.72″E

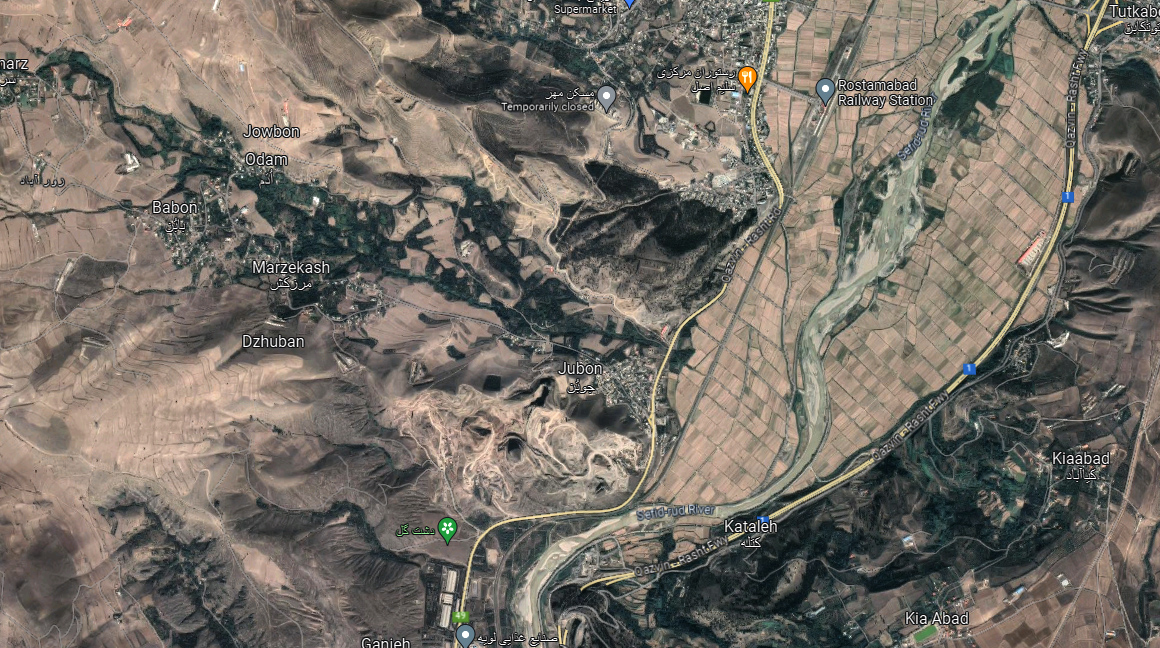

Map

The Iron Age III

History and description

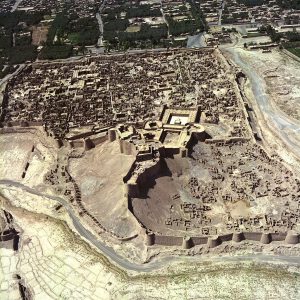

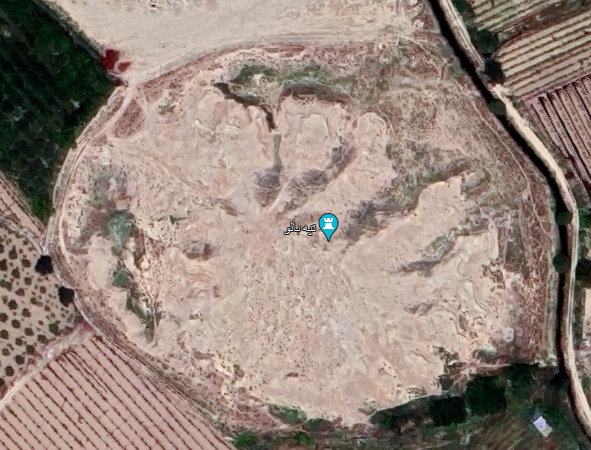

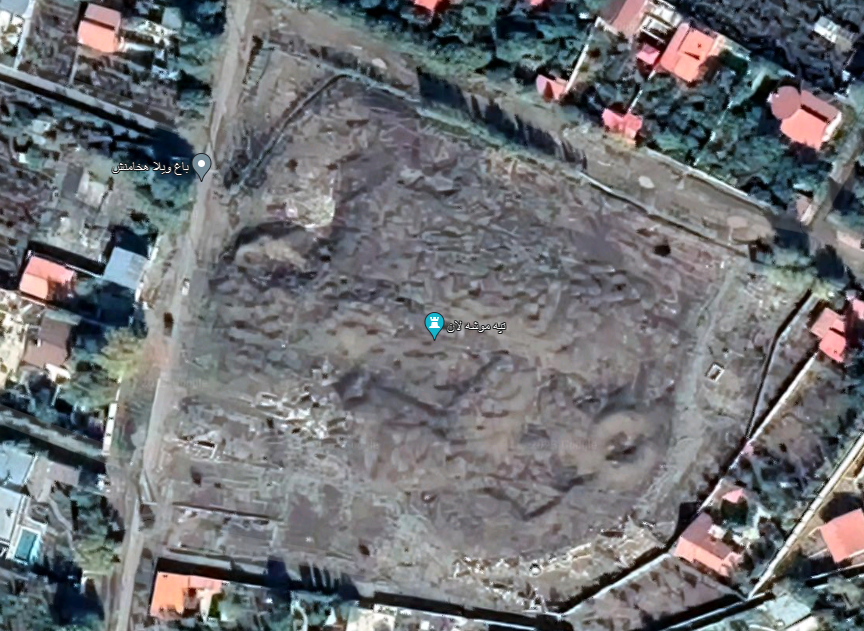

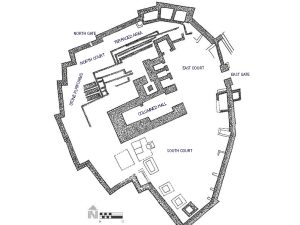

Qalāichi is the name of a mound in the vicinity of a village of the same name, located 7 km northeast of the town of Bukan. The archaeological site of Qalāich lies on a rocky outcrop 10 m high, on top of which a Mannaean fort was built (fig. 1). The extent of the fort is estimated to be 1 hectare, of which 7000 square meters have been excavated (fig. 2). The fort includes two distinct areas, a circular fortification with rectangular buttresses and a walled area that is located on a lower level, of which very few traces have survived (fig. 3). Two construction phases have been identified at the site: Ia and Ib from the top to the bottom, respectively.

Ia. This seems to be the uppermost layer mostly occupied by squatters. The architecture of this squatter phase, found mostly in the area of the columned hall (see below), consists of several small chambers with pisé walls, and inner surfaces decorated with paintings of vegetal, geometric, animal, and human motifs (Kargar, Binandeh, Khanmohammadi, Qalaichi Architecture, pp. 20, and 90). A number of glazed bricks used in the main buildings of the early phase (Ib) were reused upside down in the construction of other structures.

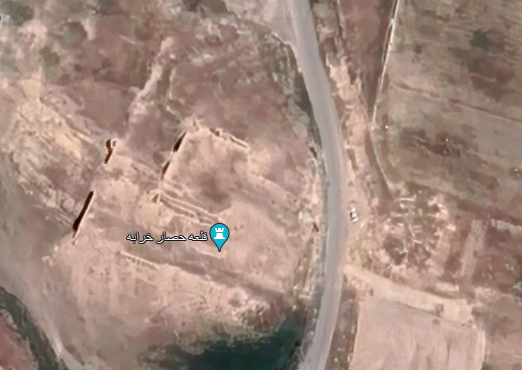

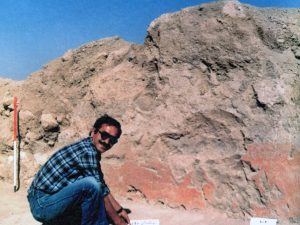

Ib. This is the main construction phase dated to the Iron Age III period. The remains of this phase include a fort on a high level and an outer wall that once protected the whole site; the wall was visible until the late 1970s but is now largely destroyed (fig. 4). The architecture of this phase consists of an enclosed area of one hectare surrounded by stone walls. The walls of the outer ramparts have two entrances; the main entrance is located on the east side and consists of a bastion on either side of the entrance as well as a guardhouse. The other small entrance that is situated on the north side was probably used for the entry of important people or emergency exits (Kargar, Binandeh, Khanmohammadi, Qalaichi Architecture, pp. 36-37). The main architectural complex consists of a columned hall (19 x 35 m) with its five adjacent rooms with a terraced area that opens onto a northern court (fig. 3). A platform for placing votive offerings is located in the middle of room No.1. The floors of rooms 3 and 4 are paved with mud-brick. The internal walls of the columned hall and rooms 3 and 4 were decorated with red and white ochre and blue paintings (fig. 5). There is a group of three stone platforms located in the northwestern part of the columned complex. Moreover, there are mud-brick platforms in the south court, some of which were decorated with glazed bricks and were most likely altars or in the open space. In addition, a waste dump was found in the northeastern part of the site, in which there were more than 5000 pieces of animal bones. The study of those bones has shown that the animals had not been butchered for their meat but were deliberately sacrificed (see bibliography under Nezamabadi et al.). This is a clear sign of the site’s function as a ritual/religious place (Hassanzadeh and Curtis, The Repatriated Bukan Glazed Bricks from Switzerland, p. 13).

Fig. 1. Tepe Qalāichi. View from the north (after Kargar, B., A. Binandeh, and B. Khanmohammadi, M’emāri-ye Tappeh Qalāichi, p. 20)

Fig. 2. Tepe Qalāichi. View from the mound in 2005 (after Kargar, B., A. Binandeh, and B. Khanmohammadi, M’emāri-ye Tappeh Qalāichi, p. 19)

Fig. 3. Plan of the excavated structures at Qalāichi (after Kargar, B., A. Binandeh, and B. Khanmohammadi, M’emāri-ye Tappeh Qalāichi, p. 25)

Fig. 4. The sketch plan of Qalāichi by Wolfram Kleiss (after Kleiss, “Burganlagen und Befestigungen in Iran,” fig. 9)

Fig. 5. Part of the red wall painting with Bahman Kargar in the foreground. The 1985 excavation (after Yaghma’i, “Yāddāshti bar nakhostin fasl-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye Qalāichi, Bukān,” p. 63).

Archaeological Exploration

The site of Qalāichi was first discovered and reported by Wolfram Kleiss in his surveys in western Iran in 1976. Kleiss wrote the name of the site as Haidar Khan Qal’eh, made a general topographic plan of the visible remains, and collected potsherds ranging in date from the Iron Age III to the Parthian periods (Kleiss, “Burganlagen und Befestigungen in Iran,” pp. 23-27, fig. 9). It took years for scholars to realize that Haidar Qal’eh Khan is indeed Tepe Qalāichi (Kroll, “The Southern Urmia Basin in the Iron Age,” p. 79). Unfortunately, the site was the object of devastating looting and destruction during the tumultuous years of the Iran-Iraq war in the early 1980s. Finally, in the spring of 1985, a team led by Esmail Yaghma’i carried out two months of rescue excavations on behalf of the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research under dangerous conditions that prevailed in the region (see bibliography under Yaghma’i). Yaghma’i excavated the surviving remains of a columned hall with its adjacent structures, including a stone stele with an inscription in Aramaic (see below). There was also the discovery of a unique grave found near the northeastern edge of the mound. The tomb and its contents had been partly destroyed but Yaghma’i meticulously retrieved the skeletal remains of possibly three individuals, including a young woman (Yaghma’i, “Yek khāksepāri-ye vizheh dar Tappeh Qalāichi, Bukān,” pp. 198-201). He also reports the presence of a looted graveyard in the vicinity of the Qalāichi village (Yaghma’i, “Yek khāksepāri-ye vizheh,” pp. 207-208). Hundreds of glazed bricks that once decorated various structures of the ancient site had been plundered before the arrival of the archaeological team. During his work at the site, Yaghma’i was able to retrieve dozens of those glazed bricks; but the majority of them had been taken away and lost (Yaghma’i, “Yāddāshti bar nakhostin fasl-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye Qalāichi, Bukan,” p. 56). The second series of archaeological exploration began after fourteen years of lapse, in the course of which the site was the object of more illicit excavations and destruction. From 1999 to 2006, Bahman Kargar conducted nine seasons of systematic excavations at the site on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research (see bibliography under Kargar).

Finds

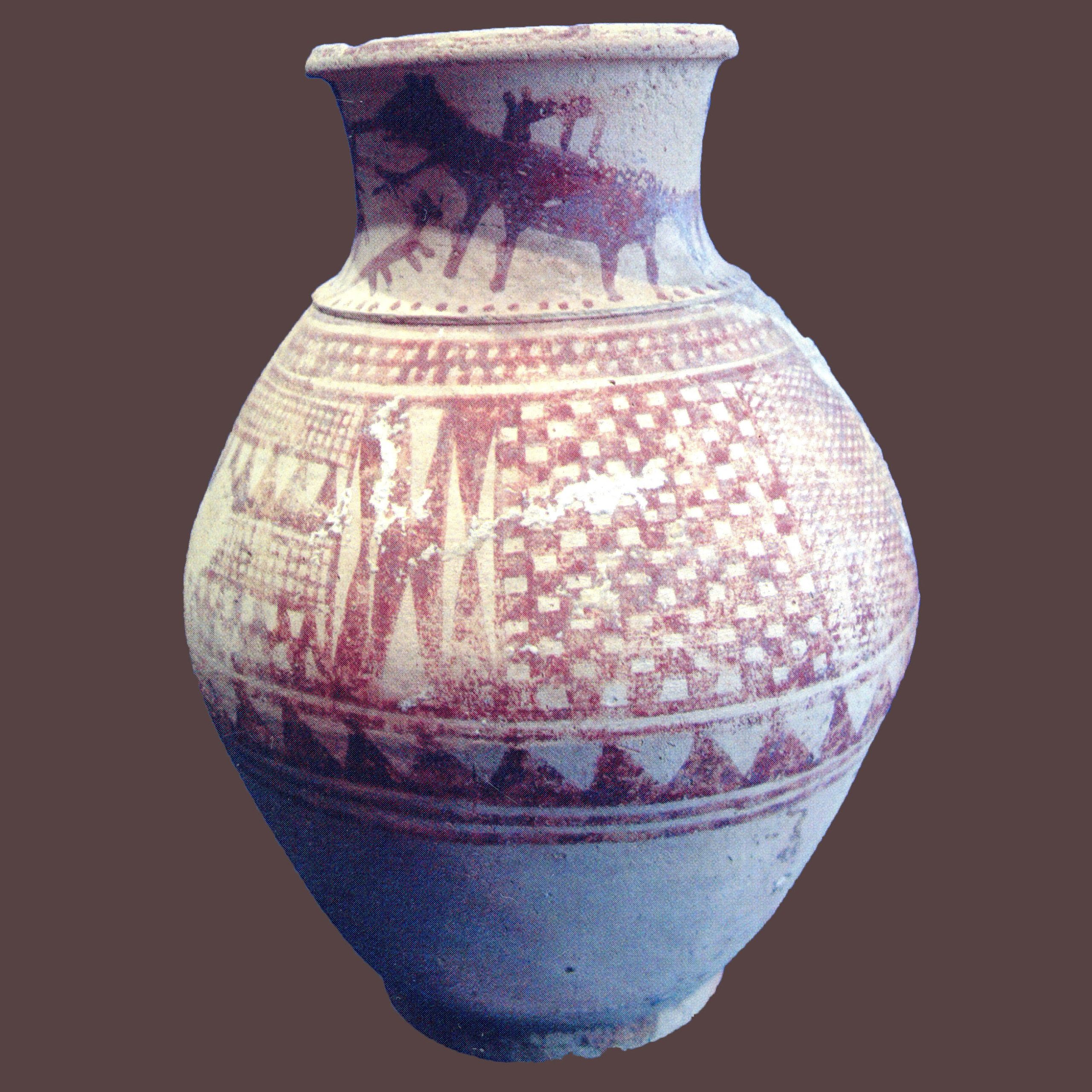

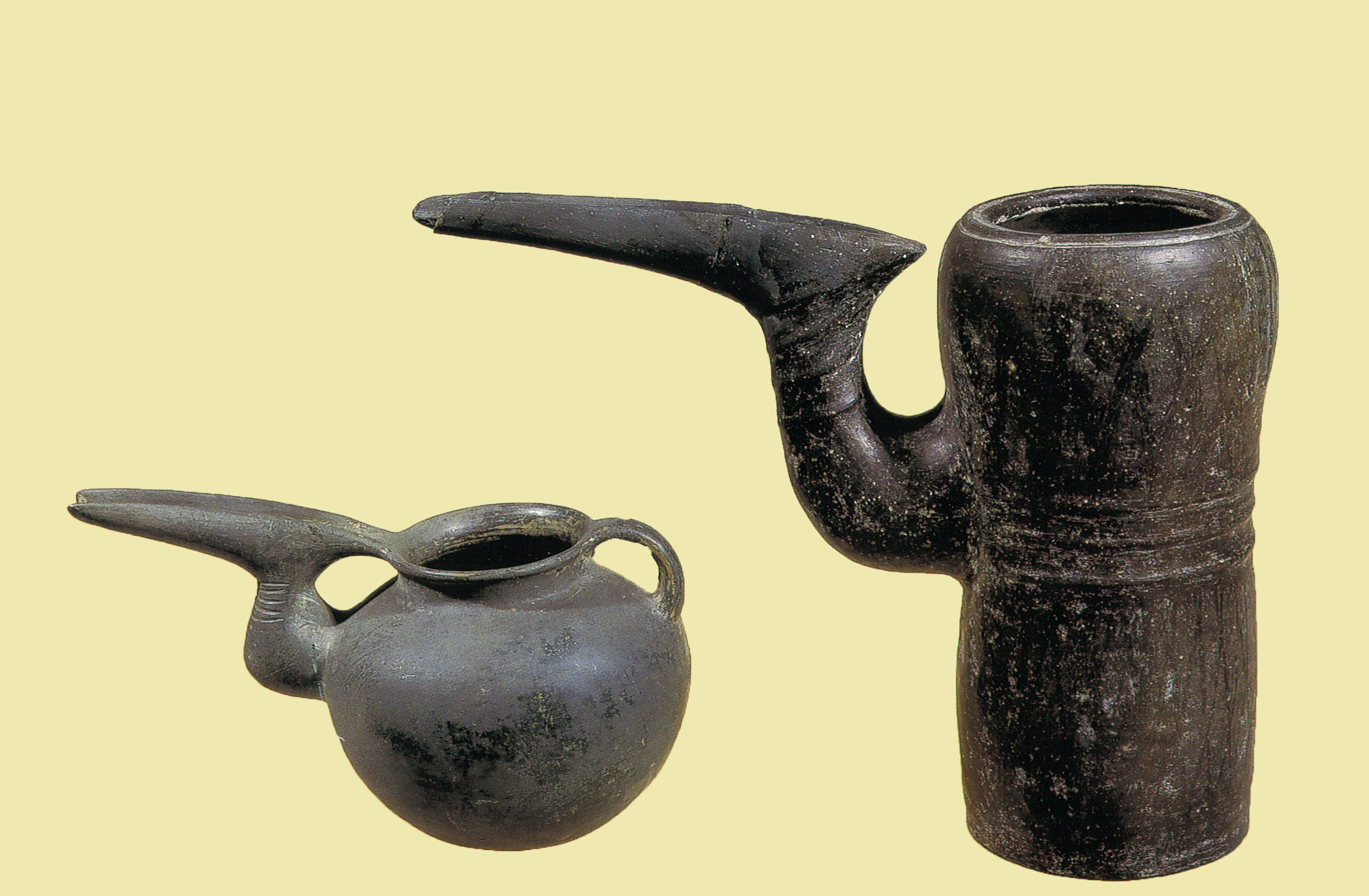

The illegal and controlled excavations at Tepe Qalāichi yielded a large number of glazed bricks, typical Iron Age III pottery (Hasanzadeh, “Madārek va shavāhed-e bāstānshenākhti,” pp. 42-47; Mollazadeh, “The Pottery from the Mannean Site of Qalaichi,”), few objects in metal, and an inscribed stele.

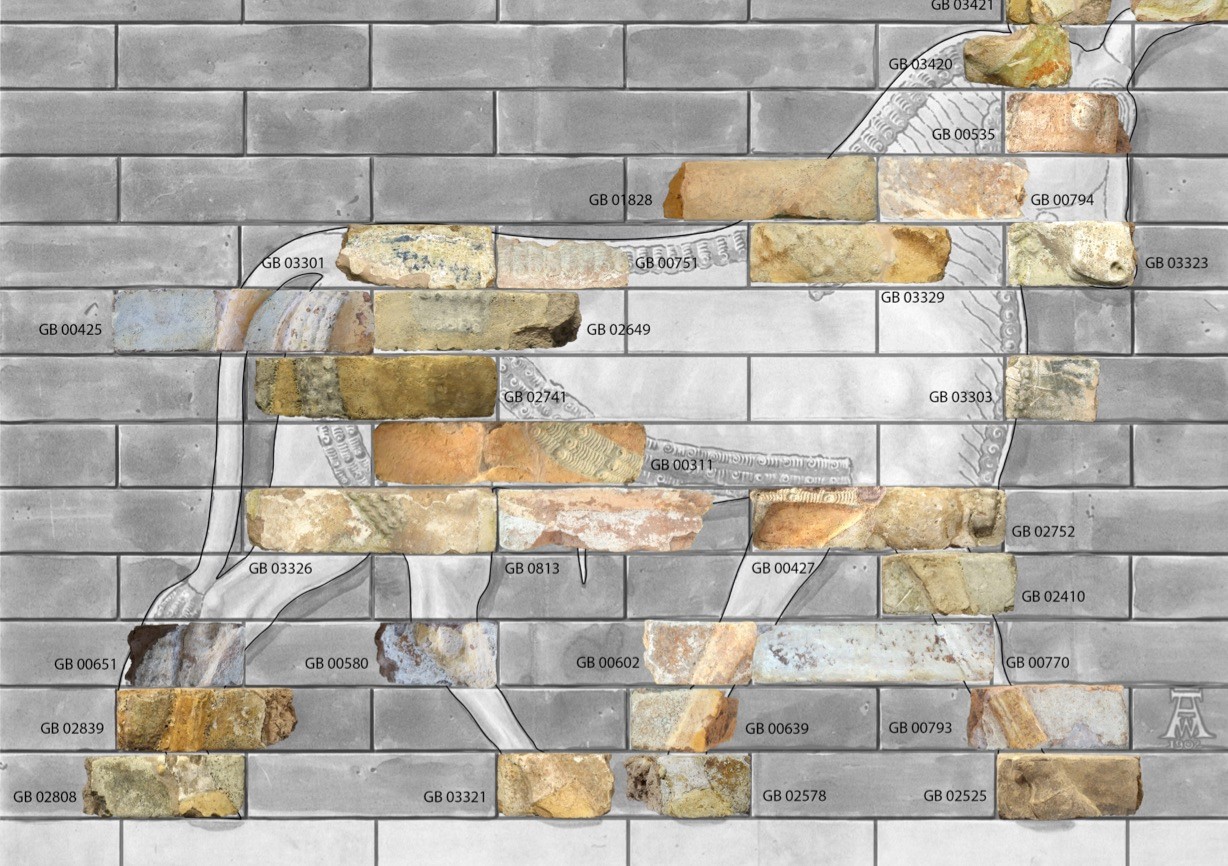

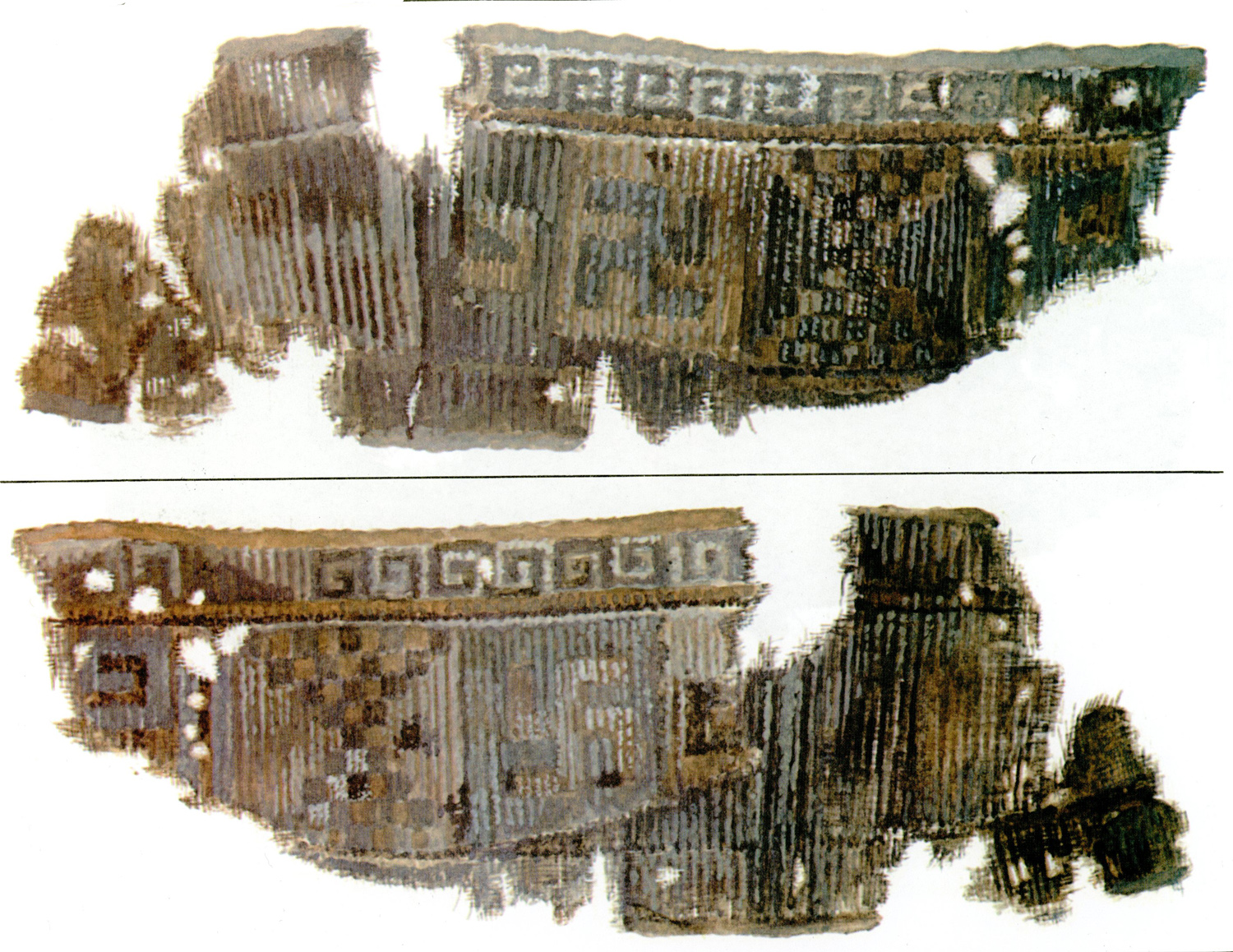

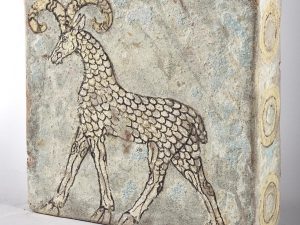

Glazed bricks: Illegally excavated polychrome glazed bricks from Qalāichi appeared on antiquities markets as early as the 1980s. More than 1500 glazed bricks have so far been found at the site or retrieved from art markets and/or antiquities dealers (figs. 6, 7, and 8). These bricks depict a variety of geometric, floral, and animal motifs. The largest ones measure 36 x 36 x 8 cm. The first publication of bricks from Tepe Qalāichi goes back to a 1983 exhibition entitled Animals in the Art of the Ancient Orient at the Ancient Orient Museum in Tokyo. In this exhibition, the photograph of a single exhibited brick acquired by the museum was published as the frontispiece of the exhibition catalogue; the brick in question was erroneously dated to 1250 B.C., indicative of its ambiguous provenance and the lack of contextual data (Tanabe 1983: 34).

Then in 1988, Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis mentions the discovery of the site, the glazed bricks, and the stele (“Report on a Short Visit to Iran,” p. 145). In 1991, Mirabedin Kaboli reported the bricks confiscated from smugglers and subsequently transported to the Iran National Museum (Kaboli, “Barresi-ye āsār-e pish az eslām”, p. 32). Ali Mousavi published a collection belonging to a Japanese collector in Paris and correctly estimated their date as being late 8th century B.C. (Mousavi, “Une brique à décor polychrome”). Mehrdad Malekzadeh published an informative note on the site and its importance (Malekzadeh, “Ajor-e loābdār”). Later, John Curtis Curtis pointed out that over 100 glazed bricks from this site were present on the antiquities market. According to Curtis, the bricks should be acknowledged as a local interpretation of the art of Assyria that was accomplished by Mannaean artists (Curtis "The Evidence for Assyrian presence,” pp. 32-34). A full study of the glazed bricks from Qalāichi is presented in two recent publications by Yousef Hassanzadeh and John Curtis (see bibliography under Hassanzadeh and Curtis; Hassanzadeh and Mollasalehi).

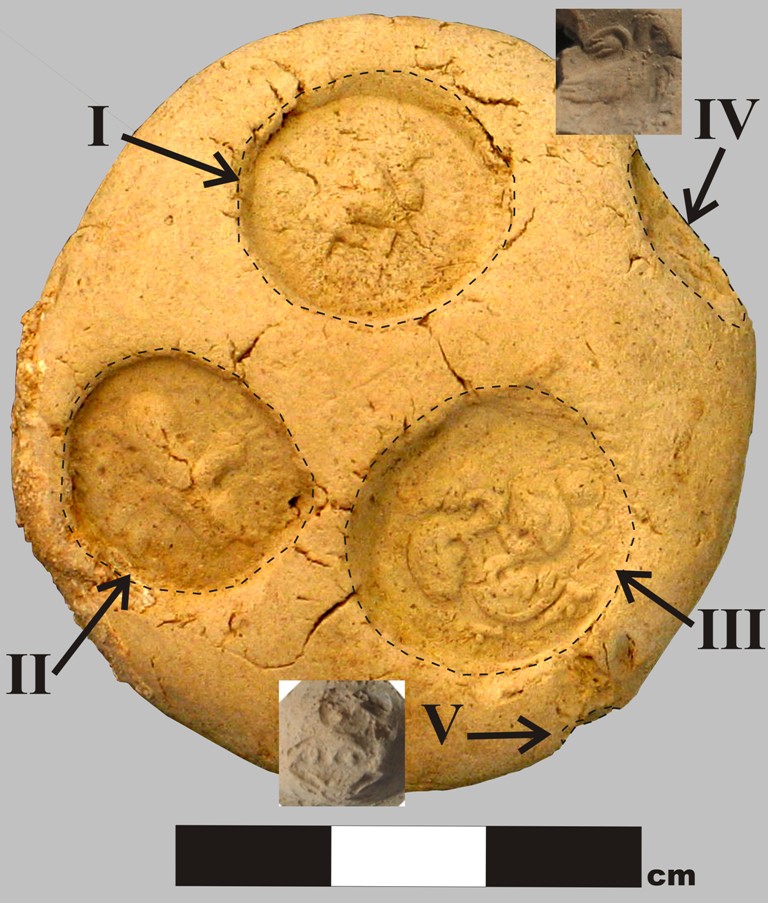

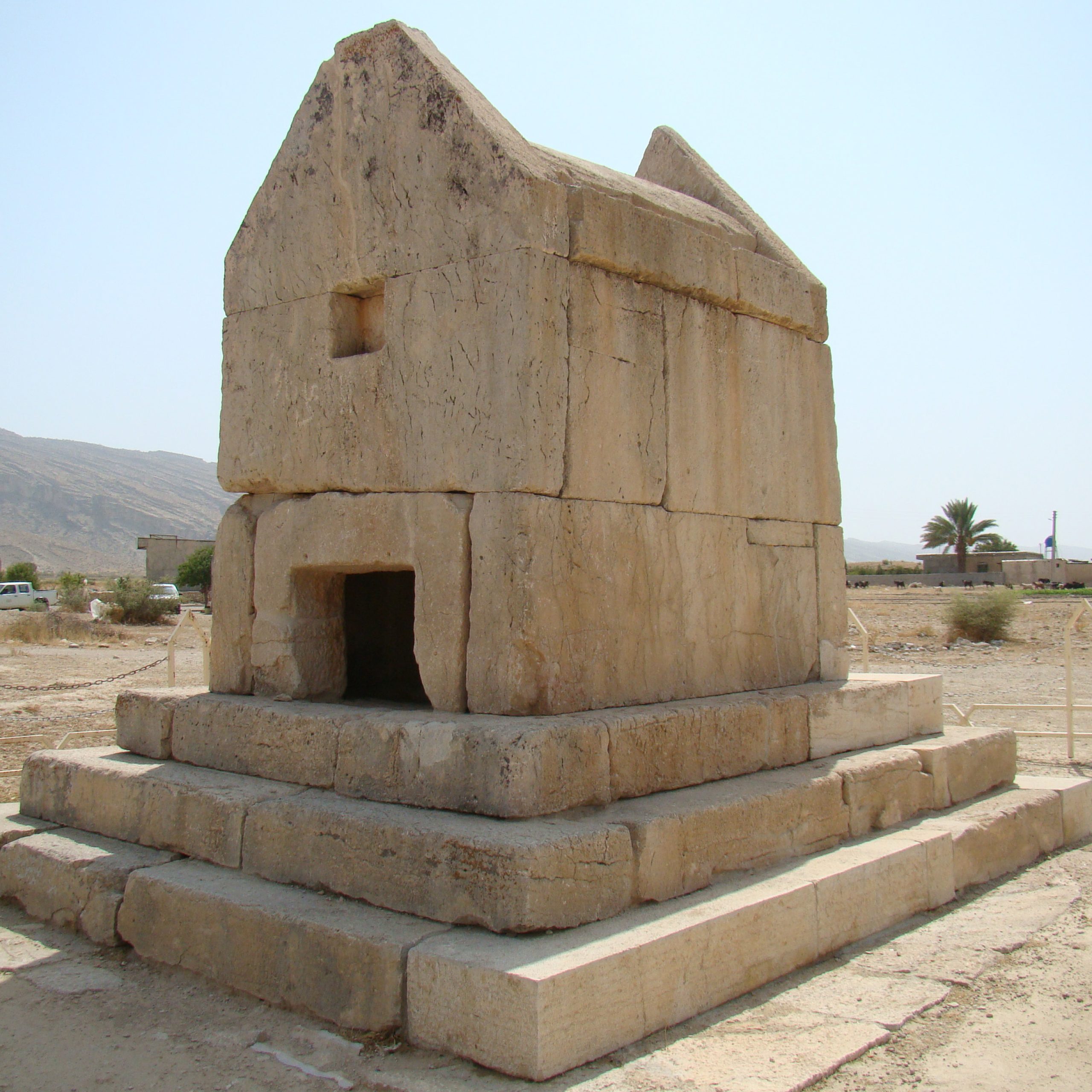

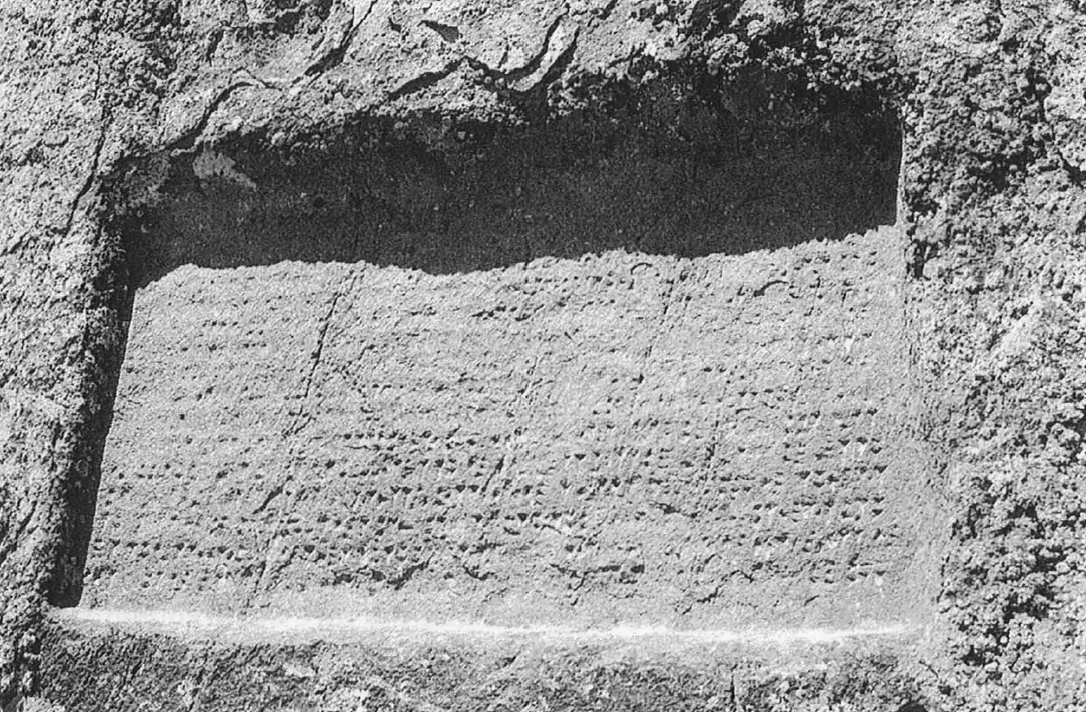

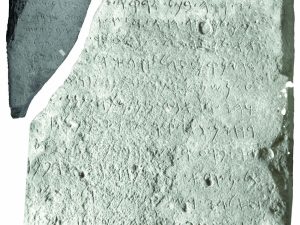

Inscription: The stele in Aramaic was found in two fragments. A large fragment of it was discovered in 1985 during Yaghmai’s excavations (figs. 9 and 10). The second smaller, but better-preserved fragment, was recovered from the antiquities market in 1990. The stone stele weighs more than 1,000 kilograms and is 178 x 60 x 30 cm. The inscription has been published and discussed by a number of scholars who date the inscription based on paleographic grounds to the end of the 8th century B.C. (see the bibliography under Bashash Kanzaq; Dara; Eph’al; Fales; Lemaire; Sokoloff; Teixidor). The two fragments once collated allow one to read 13 Aramaic lines almost completely which formed the end of the inscription and contained the Aramaic curses customary to this period, parallels of which can be found in the commemorative inscription of the Tell Fekheryeh statue. The Qalāichi stele now attests to the official use of Aramaic in western Iran, more precisely in the kingdom of the Mannaeans, two centuries before its diffusion in the Achaemenid Empire. André Lemaire’s translation of the inscription reads as follows:

“Whoever overthrows this monumental stele (either in ...)

In war or peace, whatever plague

exists on earth, be sent down on that king’s land by God

and God’s malediction falls on him

and Haldi’s malediction who reigns in ZᵓTR comes down on him. May seven cows

nurse a calf but he doesn’t become satisfied. May seven

women be cooked in a fire oven and it doesn’t become full. May

the smoke from cooking and the sound

of windmills be gone from his land. May his ground become salt pan and

May it become bitterer than poisonous grass and the king

who inscribes on this monument, may Hadad and Haldi overthrow his throne,

and may Hadad not create thunder

In his land and may ...”

Bashash Kanzaq comments that the inscription dates back to the reign of Ullūsūnū, the powerful king of Manna around 716 B.C. onwards. The inscription implies recognition of Yanzi or the ruler of ZᵓTR (Izirtu), the capital of the Mannaean kingdom, by the Gods of the royal temple and a perpetual ruling of god Haldi over that land which is Manna (“Qerā’at-e kāmel-e katibe-ye arāmi-ye Bukān,” pp. 25-29).

Fig. 6. A glazed brick with the figure of a ram on the medial side and concentric circles on the lateral side (after Hassanzadeh and Curtis, The Repatriated Bukan Glazed Bricks from Switzerland, p. 62)

Fig. 7. A glazed brick with the figure of a sphinx (after Hassanzadeh and Curtis, The Repatriated Bukan Glazed Bricks from Switzerland, p. 40)

Fig. 8. A glazed brick with the figure of a human-headed lion (after Hassanzadeh and Curtis, The Repatriated Bukan Glazed Bricks from Switzerland, p. 46)

Fig. 9. The stele at the time of discovery. The 1985 excavations (after Yaghma’i, “Yāddāshti bar nakhostin fasl-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye Qalāichi, Bukān,” p. 61).

Fig. 10. The inscribed section of the Qalāichi stele (photo: Y. Hassanzadeh)

Bibliography

Bashash Kanzaq, R., “Qerā’at-e kāmel-e katibe-ye arāmi-ye Bukān,” Proceedings of the First Symposium on ancient languages, inscriptions, and texts, Tehran, 1375/1996, pp. 23-40.

Curtis, J., “The Evidence for Assyrian Presence in Western Iran,” Sumer, vol. 51, No. 1 & 2, 2001-2002, pp. 32-37.

Curtis, V., “Report on a Recent Visit to Iran”, Iran, vol. 26, 1988, p. 145.

Dara, M., “Stel-e arāmi-ye Qalāichi-ye Bukān: katibeh-ye būmi-ye mantaqeh yā vāredāti?,” Zabanshenakht, vol. 10, 1398/2019, pp. 19-39.

Eph’al, E., “The Bukan Aramaic Inscription: historical considerations”, Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 36, 1999, pp. 116-112.

Fales, F. M., “Evidence for West-East Contacts in the 8th BC: the Bukan Stele”, in Continuity of Empire (?) Assyria, Media, Persia, G. B. Lanfranchi and M. Roaf and R. Röllinger (eds.), Padova, 2003, pp. 131-148.

Hassanzadeh, Y., “Madārek va shavāhed-e bāstānshenākhti az mohavate-ye Qalāichi,” in Barresi-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye mohavate-ye mānāi-ye Qalāichi, Bukan, Y. Hassanzadeh and H. Mollasalehi (eds.), Tehran, 1396/2017, pp. 25-54.

Hassanzadeh, Y. and S. Piran, “Negārehā-ye tarsim shodeh bar ajorhā-ye loābdār-e Bukān,” in Barresi-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye mohavate-ye mānāi-ye Qalāichi, Bukan, Y. Hassanzadeh and H. Mollasalehi (eds.), Tehran, 1396/2017, pp. 71-134.

Kaboli, M., “Barresi-ye āsār-e pish az eslām dar majmū’e-ye bāzyāfteh”, Mirās-e Farhangi, Nos. 3-4.

Kargar, B., “Qalāichi: Zirtu, markaz-e Mānā: lay-e Ib, 1378-1381”, in Proceedings of the International Symposium on Iranian Archaeology: Northwestern Region, M Azarnoush (ed.), Tehran 1393/2004, pp. 229-245.

Kargar, B., A. Binandeh, and B. Khanmohammadi, “Excavations at Tepe Qalaichi, a Mannaean Site in Western Azarbaijan,” Studia Iranica, vol. 49, 2020, pp. 33-55.

Kleiss, W., “Burganlagen und Befestigungen in Iran,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 10, 1977, pp. 23-52.

Kroll, S., “The Southern Urmia Basin in the Early Iron Age,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 40, 2005, pp. 65-75.

Lemaire, A., “L'inscription araméenne de Bukân et son intérêt historique”, Comptes-rendus de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 142e année, No. 1, 1998, pp. 293-300.

Lemaire, A., “Une inscription araméenne du VIIIe s. av. J.-C. trouvée à Bukân (Azerbaïdjan Iranien),” Studia Iranica, vol. 27, 1998, pp. 15-30.

Malekzadeh, M., “Ajor-e loābdār-e no’e Bukāndar muze-ye sharq-e kohan-e Tokyo,” Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, vol. 17, pp. 75-76.

Mollazadeh, K., “The Pottery from the Mannean Site of Qalaichi, Bukan (NW-Iran)”, Iranica Antiqua, vol. 43, 2003, pp. 107-125.

Mousavi, A., “Une brique à décor polychrome de l’Iran occidental (VIIIe-VIIe s. av. J.-C.,” Studia Iranica, vol. 23, 1994, pp. 7-18.

Sokoloff, M., “The Old Aramaic Inscription from Bukan: A Revised Interpretation”, Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 49, 1999, pp. 105-115.

Tanabe, K., Animals in the Arts of the Ancient Orient, Tokyo, Ancient Orient Museum, Tokyo, 1983.

Teixidor, J., “L’inscription araméenne de Bukan, relecture”, Semitica, 49, 1999, 117-121.

Yaghma’i, E., “Kashf-e ma’bad-e sehezār sāleh dar Bukān, ” Keyhan, Esfand 21, 1364/1985, p. 6.

Yaghma’i, E., “Yāddāshti bar nakhostin fasl-e kāvoshhā-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye Qalāichi, Bukān,” in Barresi-ye bāstānshenākhti-ye mohavate-ye mānāi-ye Qalāichi, Bukan, Y. Hassanzadeh and H. Mollasalehi (eds.), Tehran, 1396/2017, pp. 55-69.