Naqsh-e Rōstamنقش رستم

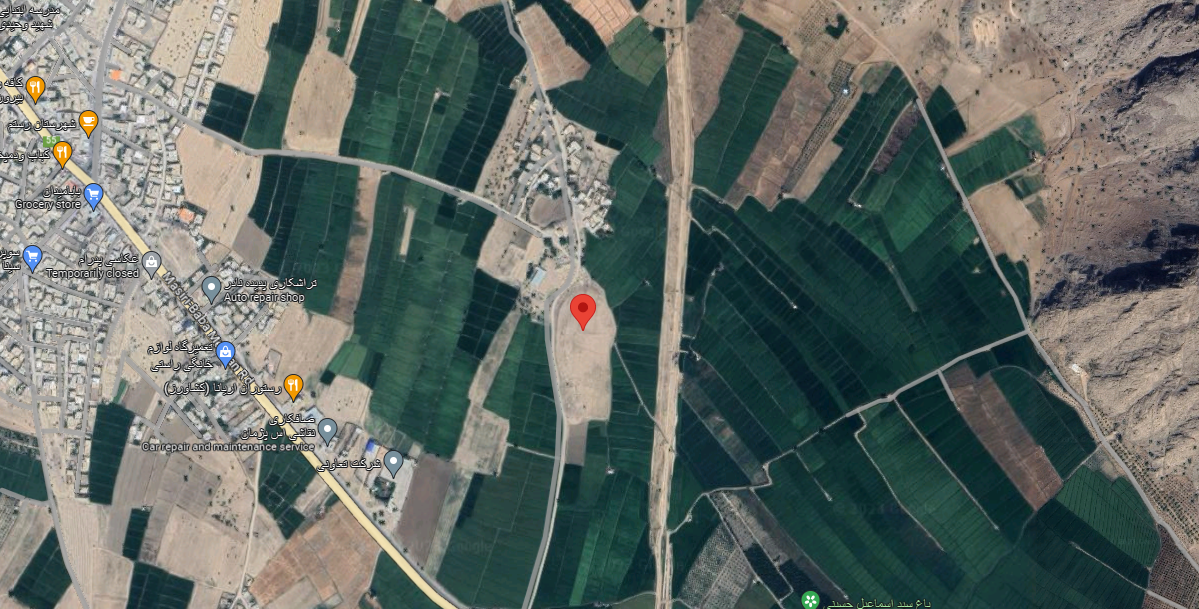

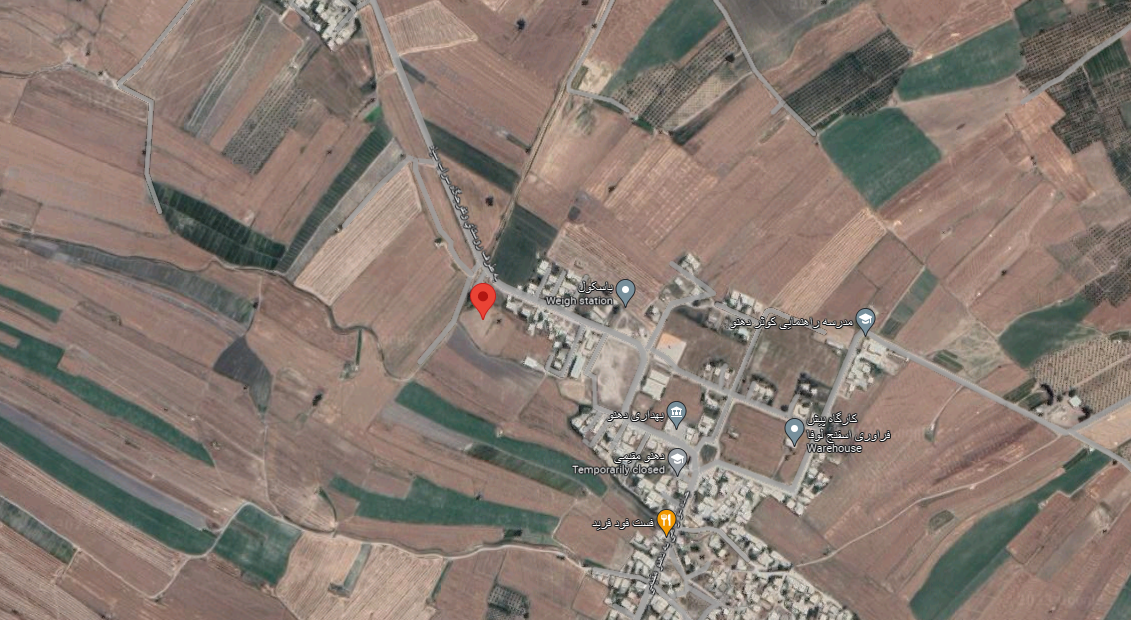

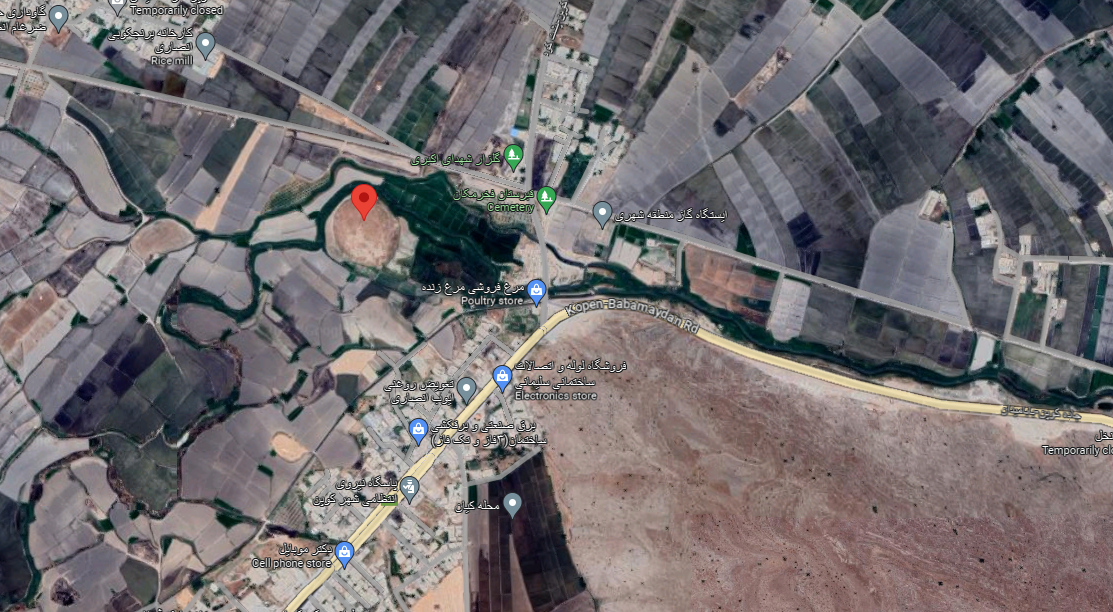

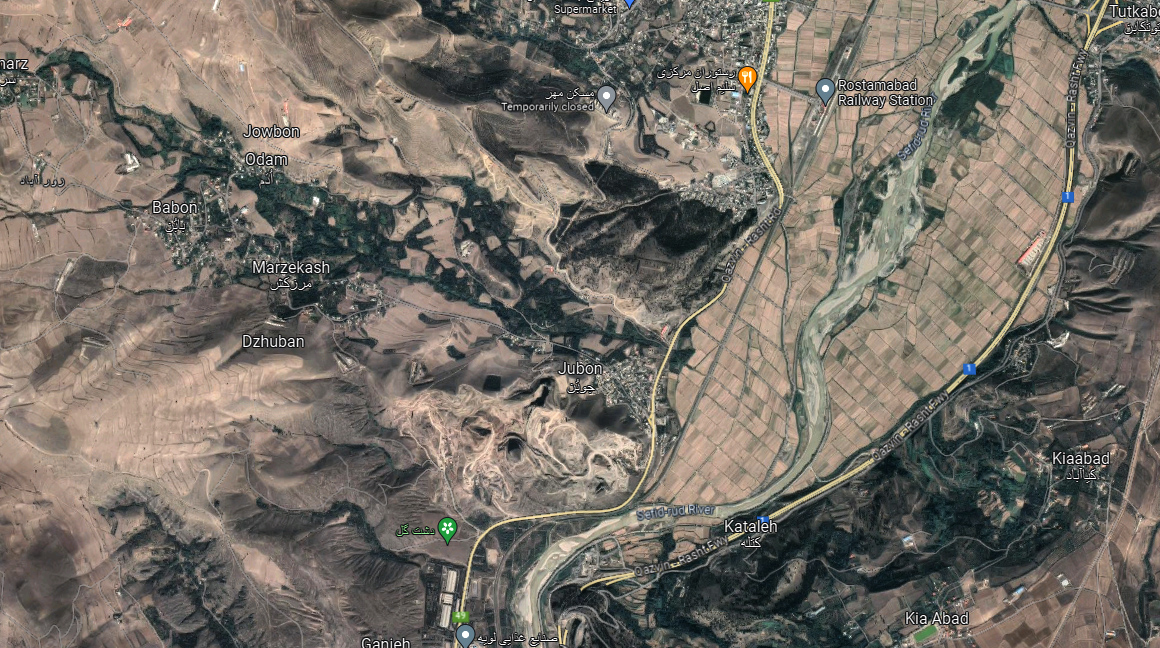

Location: Naqsh-e Rostam is a cliffside located on Hossein Kuh, 4 km north of Persepolis, southern Iran, Fars Province.

29°59’20.7″N 52°52’26.5″E

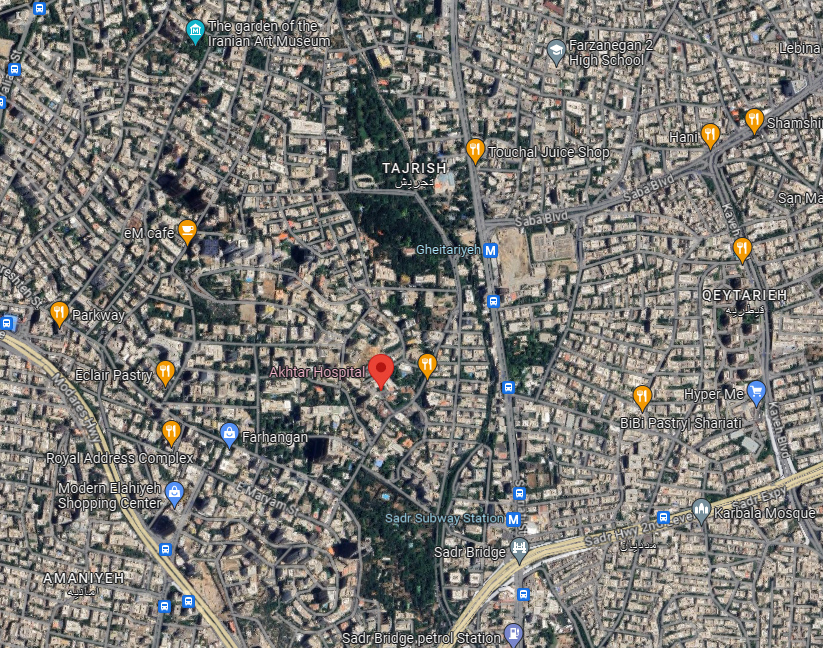

Map

Historical Period

Elamite, Achaemenid, Sasanian, Islamic

History and description

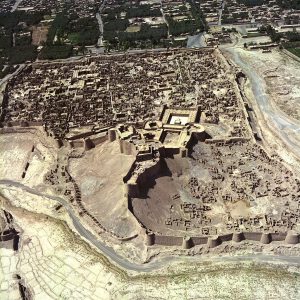

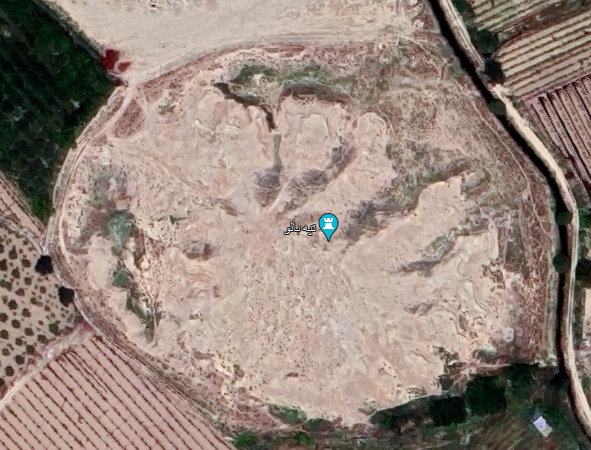

Naqsh-e Rōstam is the local name for a cliffside on the south side of Hossein Kuh, 4 km north of Persepolis (fig. 1). The cliffside marks the southeastern end of the mountain and overlooks the Marvdasht plain. A stretch of two hundred meters of the cliffside was selected to accommodate important monuments dating back to the time of the Elamites, the Achaemenids, and the Sasanians.

The remains at Naqsh-e Rōstam consist of 23 monuments, including the Achaemenid rock-cut tombs, bas-reliefs of various periods, and free-standing architectural buildings and structures.

II. The Achaemenid rock-cut tombs.

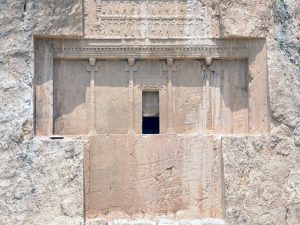

Because of its antiquity since the time of the Elamites, Darius I chose the cliffside to be the site of his tomb. The tombs’ façades are all alike. It consists of a carved-out cruciform depression with three main areas (fig. 2). The upper arm of the cross, 8.50 m high, is decorated with the standing figure of the king on a podium of steps in front of the fire altar. Above his head hovers the winged figure, identified by some as the representation of Ahūrāmazdā, and interpreted by others as the symbol of the farr-e kiānī or faravahar. The king stands on a throne carried by thirty representatives of the empire’s nations. For the tomb of Darius I, there are two long inscriptions placed on the left side of the upper register, behind the king’s figure. Inside the carved-out area, there are figures of guards and soldiers. The topmost of the three figures depicted on the left panel, behind the king, is identified thanks to a trilingual inscription as Gobryas, a Patishorian, spear-bearer of Darius the king. Some scholars believe that this is the same Gobryas, the son of Mardonius, mentioned in the Bisutūn inscription of Darius the Great. The median register, 14 x 7.60 m, is decorated like the façade of a palace with engaged columns and bull-headed capitals supporting a beamed roof. The entrance is also treated as a palace door. The entrance was meticulously closed with an imposing stone door. The interior of the tomb chamber contains nine graves hewn out of the rock. The lower register or arm of the cruciform tomb has been left blank. According to the archaeological excavation results, the original floor at the foot of the cliff was, at least, 5 m below the present-day ground.

The other rock-cut tombs imitating the shape of the tomb of Darius I, have presumably been attributed to Xerxes (for the tomb carved on a protruding wall of the cliff, to the right of the tomb of Darius I), Artaxerxes I (to the left of the tomb of Darius I), and Darius II (carved to the left of his father’s tomb, Artaxerxes I). However, the interior of these rock-cut tombs differs in both size and the number of graves they contain.

I. The bas-reliefs.

II.1. The Elamite bas-relief (fig. 3). At a lower level, almost the entire face of the cliffside is decorated with bas-reliefs of various periods. The oldest one is the eroded and largely erased Elamite rock relief. The Elamite relief is carved on a rectangular panel 7 x 2.5 m depicting the figures of a god and a goddess seated on thrones of coiled snakes. Parts of the coiled seats and one of the figures are still visible on the right side of the panel. On either edge of the scene, there are two figures: one depicting a standing king (at right), and another individual whose crowned head is still visible. As for the date of the Elamite bas-relief, scholars suggest that it was carved in two phases, the central scene was carved in the late second millennium B.C.; later, around 700 B.C., in the Neo-Elamite period, the figures of the king and a queen were added to the scene.

II.2. The Sasanian bas-reliefs: In chronological order, given its historical significance, the cliffside of Naqsh-e Rōstam became the frontispiece of monumental rock reliefs in the early Sasanian period.

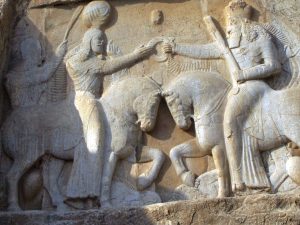

II.2.1. The Investiture Relief of Ardashir (fig. 4). At the easternmost end of the cliff, where it overlooks the turn of the present-day road to the north, stands a large rock-cut panel representing Ardashir Papakan, the founder of the Sasanian Empire, receiving his ring of power from the personification of his god, Ahurāmāzdā. Today, the carved panel stands about 2 m. above the ground; its width ranges from 6.30 m to 6.65 m; its height is 2.40 m. The two main equestrian figures, Ardashir and Ahurāmāzdā, are both represented in profile. Ardashir’s figure is on the left side. He wears a crown and with his right hand, he is to receive the ring of power while his left hand is half raised and has opened the index figure forward as a sign of respect. With his horse, he tramples the body of his enemy, most probably the last of Parthia, Artabanus V. Behind the king’s figure, there is an attendant with a fly-whisk. The god’s figure is depicted on the left side, wearing a crenelated crown resembling that of ancient Persian kings. Ahūrāmazdā stretches his right hand and offers the symbol of kingship to Ardashir; his left hand is half raised, holding a long staff. The god’s horse tramples an individual, representing the personification of evil or Ahriman. An inscription in three versions ˗ Sasanian Middle Persian Sasanian, Parthian Middle, and Greek ˗ is carved on the body of the horses, identifying both Ahūrāmazdā and Ardashir. Scholars tend to date this investiture scene to the late years of Ardashir’s reign, c. 235 A.D.

II.2.2. The Victory Scene of Shapur I (fig. 5). The bas-relief commemorating Shapur’s triumph over Roman armies is the largest bas-relief at Naqsh-i Rōstam, which has been carved a few meters below the tomb of Darius I. The large rectangular panel that measures 13 x 6 m depicts the more-than-life-size figure of Shapur I on a horse with his typical large crown. In front of the king’s figure are two individuals, one standing and the other kneeling. The standing man’s hands are grasped by the monarch. The other figure is depicted rushing forward with open arms and prostrating himself before Shapur. The standing man has been identified as the Roman emperor Valerian whom Shapur captured alive, and whose hands he holds as a sign of captivity. The kneeling figure has been identified as Philip the Arabian who surrendered and concluded a peace treaty with the Sasanian king. Given the presence of the figure of Valerian, this victory scene must have been carved after 261 A.D. To the right of the panel, there is the bust of Kartir, the high priest of the Sasanian Empire, accompanied by an inscription in Middle Persian. Kartir is depicted wearing a half-cylindrical hat recognized in his other reliefs (such as in Naqsh-e Rajab). His right hand is half-raised and his index finger points toward Shapur as a gesture of praise and respect. A long, important inscription in Middle Persian is carved below the High Priest’s bust. Kartir’s figure and inscription were added later, during the reign of Bahram II, probably around 280 A.D.

II.2.3. Bahram II and Dignitaries (fig. 3). This bas-relief of Bahram II on a panel that measures 5 x 2.30 m. was carved on an older Elamite sculpture (see above). Sasanian sculptors were possibly responsible for erasing the Elamite relief to make room for relief for the bas-relief of Bahram II. The location of Bahram II’s bas-relief, supplanting the old Elamite scene and close to the investiture scene of the empire’s founder, Ardashir, was carefully chosen. The king’s larger-than-life-size figure shows him standing in the center, with his body facing forward and head turned in profile to the left. He wears a winged crown with ribbons topped with a korymbos. His two hands rest on the hilt of a long sword suspended in front of him from a baldric. Five figures are depicted to the left of the panel; except for the figure of the High Priest Kartir, they are all members of the royal family. They are distinguished by their headgear. The figure carved in the extreme left end of the panel may well represent Narseh, the youngest son of Shapur I. Next to the monarch stands the queen. To the right, three dignitaries have been sculpted. All are depicted in bust form, their faces in profile, gazing towards the sovereign. The date of this bas-relief is estimated at 290 A.D.

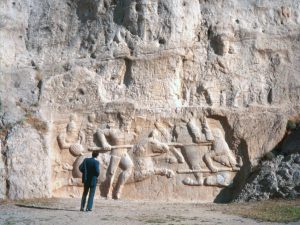

II.2.4. The Equestrian Battle Scene of Bahram II (fig. 2). The double bas-reliefs are carved below the tomb of Darius, occupying a surface of approximately 7 x 5.80 m. Two equestrian battles have been grouped on a single bas-relief. They are separated by a narrow horizontal band. On the upper panel. Bahram II on horseback gallops toward his opponent. He is dressed in chainmail, holding a lance in his right hand. The opponent is depicted as being thrust backward as if he is struck by the king’s lance. Behind the king, to the left, a standard-bearer is depicted on horseback. The body of a man is lying under the king’s horse. On the lower panel, a young knight or prince is shown on the left similar to the king’s attitude depicted on the upper panel. He wears a helmet and holds a lance. A man is lying under his horse. The opponent on horseback, also galloping, tightens the reins with his left hand, and holds a lance raised behind him with his right hand.

II.2.5. The Investiture of Narseh. A large panel, 5.65 x 3.50 m, is carved in the lower section of a protruding part of the cliffside between the tombs of Darius I and Xerxes. The scene depicts Narseh receiving the symbol of kingship from the goddess Anahita. A young prince stands between them; some scholars identify him as Narseh’s grandson. Behind the king’s figure, there is another royal individual identified as the crown prince who became king as Hormūzd II. There are two other individuals, whose figures have been eroded, attending the ceremony. The scene has been dated to the turn of the century, around 300 A.D.

II.2.6. The Equestrian Battle Scene of Hormuzd II (fig. 6) Below the Tomb of Artaxerxes I, two bas-reliefs depict riding battles and jousting scenes. The upper panel, largely eroded, is attributed to Azar-Narseh, who briefly ruled from 302 and 304 AD, and the lower one to Hormūzd II. The lower panel was discovered in Erich Schmidt’s excavations in 1936, and attributed to Hormūzd II by Roman Ghirshman. The panel of Hormuzd II’s equestrian fight is 8.40 m long and 4 m high. The scene shows the king riding on a horse and attacking his enemy with his lance. The opponent and his horse are about to fall. Behind the king’s figure, a standing man is wearing a helmet and holding a standard. Scholars have identified him as a Sasanian prince or noble. The date of the bas-relief must be around 305 A.D.

II.2.7. The Bas-relief attributed to Azarnarseh: Above the bas-relief of Hormuzd II, there is an eroded and unfinished bas-relief that was carved later than the lower panel. There are still traces of an enthroned king in front view holding a sword, and vague outlines of two standing figures to the right. Schmidt identify the main figure as Azarnarseh, the son of Hormuz II, who ruled for a few years only. The date of the scene is tentatively 309 A.D.

II.2.7. The Equestrian Battle of Shapur II. Beneath the rock-cut tomb attributed to Darius II, another large panel, 7.6 x 3 m, is carved depicting Shapur II attacking his enemy. The king rides on his horse, rushing toward his opponent whose horse is struck by the force of the king’s lance. A standard-bearer is carved behind the king’s figure. The scene commemorates one of Shapur II’s victories over the Romans, probably that of the defeat of Emperor Julian at the Battle of Ctesiphon in 363 A.D.

II.2.8. The unfinished rock-relief: To the right of the bas-relief of Narseh there is a large panel designed for the largest bas-relief of the site. There was nothing but three holes on the carved-out panel until 1821 when a local governor had the text of the deed to the property of the village of Hajiābād carved on the panel. The panel is similar to a much larger one at Bistun and has tentatively been attributed to the period of Khosrow II (r. 591-628 A.D.).

II.2.9. Further small rock carvings were identified in 1971 and published by Michael Roaf. One depicts a leaping lion, and the other is an unfinished figure of a standing man.

III. Architectural remains.

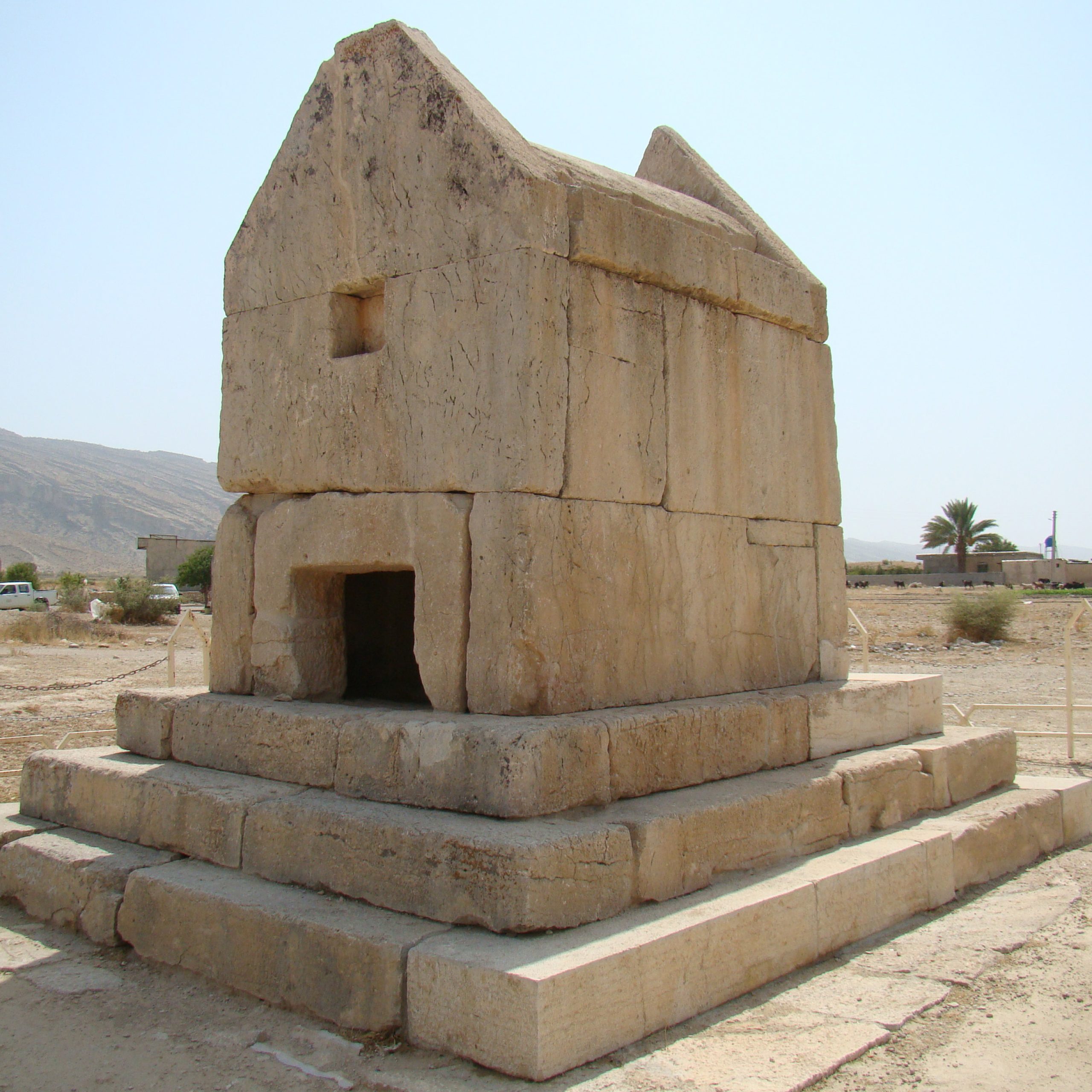

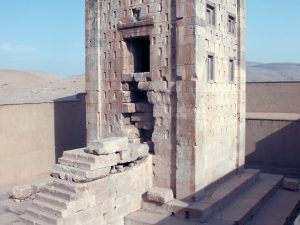

III.1. The Ka’bah Zartosht (fig. 7). The well-preserved stone building known as Ka’bah Zartosht (Cube of Zoroaster) has a cubic form, particularly before the archaeological excavations conducted in the 1930s.

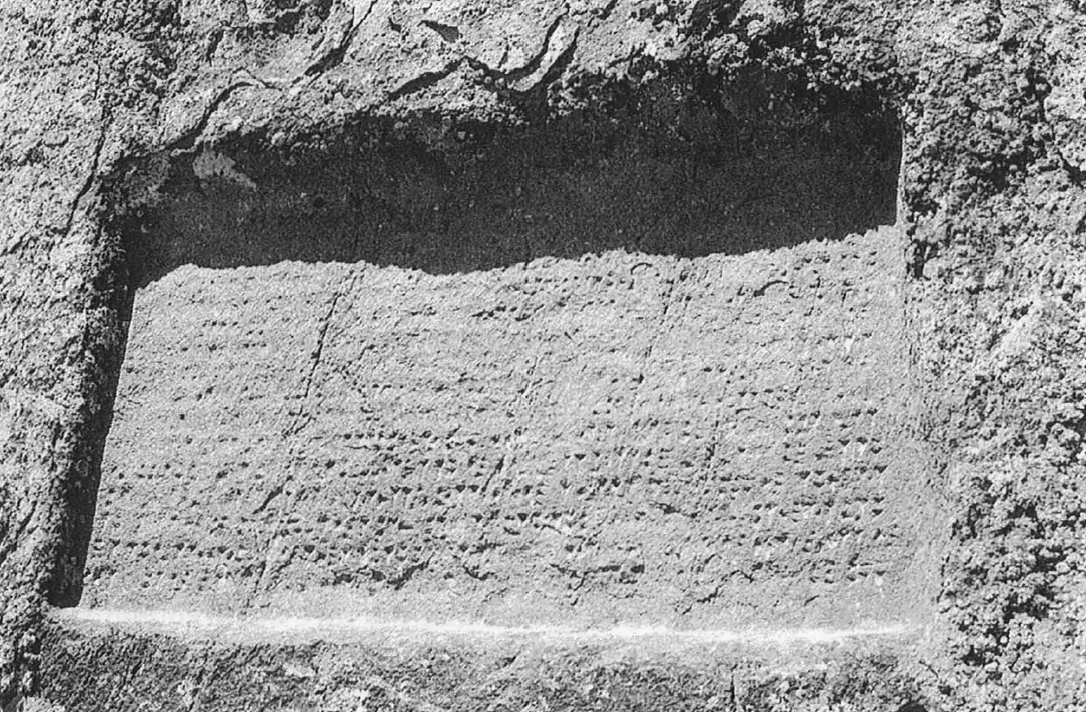

The tower (fig. 8) has a nearly square plan, measuring approximately 7.30 m on each side. Its corners are embellished with engaged piers, protruding about 20 cm. The tower sits on three plinths and its total height is 14 m. The tower of Ka’bah Zartosht resembles very much the one known as Zendan-e Soleyman at Pasargadae. The tower is capped with a pyramidal roof made of four massive slabs that stretch across the structure. There are three rows of false windows on three sides of the building. On the fourth side, there was a staircase, leading to a single room or chamber in the upper part of the building. The room is roughly square (3.72 x 3.74 m.). The tower has been regarded by scholars either as a tomb, a fire temple, or a depository, but this now fragmentary construction continues to defy a reliable interpretation.

The tower gained fame in the early Sasanian period due to Shapur I’s long inscription in three versions placed on the lower section of its walls. According to Schmidt, who excavated the area around the tower, the position of the inscription suggests that when it was carved, the ground level around the tower must have been equal to or lower than the middle step of the tower’s base. This means that the texts were visible at an eye level.

III.2. A cistern with a pentagonal orifice was cut into bedrock near the cliff side. Schmidt attributes it to the Achaemenid period.

III.3. The rock-cut couch: a stepped structure carved from bedrock on top of the cliff is interpreted as a shrine and attributed to the Achaemenid period.

III. 4. The twin structures: Approximately 150 meters north-northwest from the western edge of the cliff, two structures hewn from bedrock, stand at the base of the west slope of the mountain. The structures, often interpreted as fire altars, are now considered as being astodans or ossuaries from the Sasanian period.

III.5. The single ossuary: an astodan or stone ossuary is also carved out on top of the cliff.

III.6. The entire area of Naqsh-e Rostam was protected by a mud-brick wall built in the Sasanian period. The southern stretch of the enclosure, running nearly parallel to the cliff, measures nearly 200 meters in length with its seven semicircular towers. Towards the east, only a curtain wall (approximately 24 meters long) and a segment of an additional tower have been identified, indicating that both the eastern and western parts of the enclosure were contiguous with the cliff.

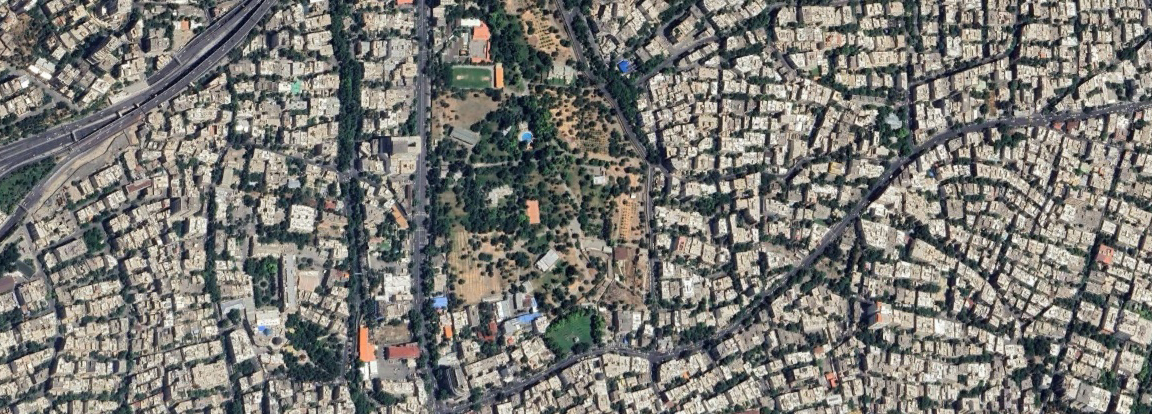

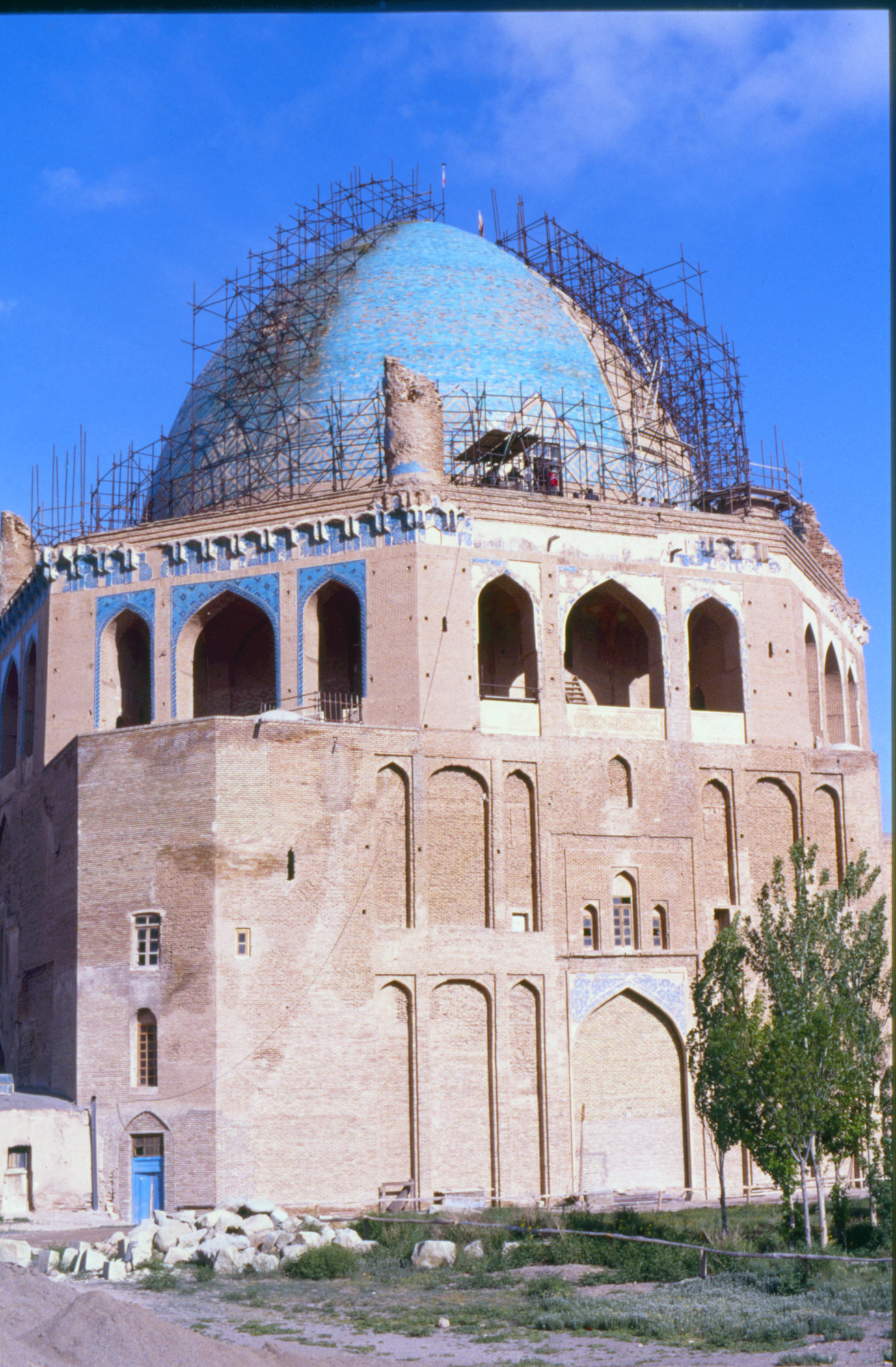

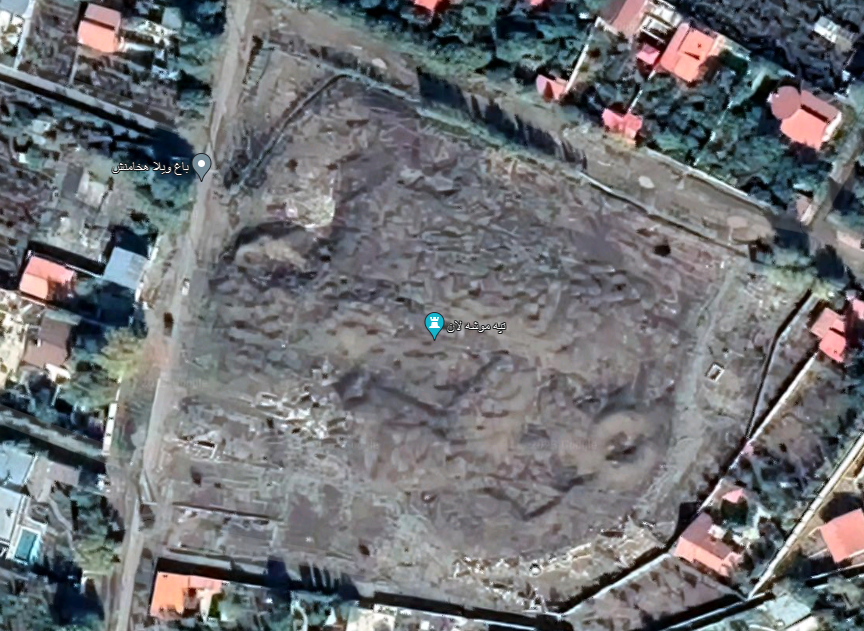

Fig. 1. Aerial view of Naqsh-e Rōstam (image: H. Karimpouri)

Fig. 2. Naqsh-e Rōstam. Tomb of Darius the Great. Below are the Sasanian rock reliefs depicting equestrian combats of Bahram II (image: courtesy of Carole Raddato, www.followinghadrianphotography.com).

Fig. 3. Naqsh-e Rōstam. The bas-relief of Bahram II was carved on an earlier Elimte bas-relief, traces of which are still visible on the end of the carved surface at the left.

Fig. 4. Naqsh-e Rōstam. The Investiture of Ardashir.

Fig. 5. Naqsh-e Rōstam. The Victory Scene of Shapur I over Roman Emperors.

Fig. 6. Naqsh-e Rōstam. The equestrian combat of Hormuzd II.

Fig. 7. Naqsh-e Rōstam. General view of Ka’beh Zartosht.

Fig. 8. Naqsh-e Rōstam. Ka’beh Zartosht.

Archaeological Exploration

The cliffside of Naqsh-e Rostam dotted with its impressive rock-cut tombs and bas-reliefs has been visible to any traveler taking the Shiraz-Isfahan road. The earliest mention of the remains is by Josafat Barbaro, a Venetian ambassador and merchant, who briefly visited the ruins at Persepolis and other adjacent sites in 1476. Unfamiliar with the remains he was visiting, Barbaro mistook the reliefs and sculptures of Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rustam for depictions of biblical figures such as Solomon. In his travel account of 1638, Sir Thomas Herbert gives the first comprehensive description of the remains at Naqsh-e Rostam, once more, with limited knowledge of the historical significance attached to these monuments. The first schematic views of the monuments at Naqsh-e Rostam were first produced during Jean Chardin’s visit of 1673-74. This was followed by another series of schematic views that Englbert Kaempfer published in his Amoenitatum exoticarum in 1712. More detailed drawings were made from the monuments by Samuel Fowler and published in Persepolis Illustrata in 1739. Robert Ker Porter, the British traveler and artist, took the first accurate views of the monuments during his visit in 1818. With his eloquent style, Ker Porter describes the mountain and its monuments as follows (Travels, vol. 1, p. 516):

“The face of the mountain is almost a perpendicular cliff, continuing to an elevation of scarcely less than three hundred yards; the substance is a whitish kind of marble. In this have been cut the celebrated sculptures and excavations, so long the subjects of discussion with the traveller, the artist, and the antiquary. These singular relics of Persian greatness are placed very near each other, and are all contained within the space of not quite the height of the mountain. Those highest on the rock are four; evidently intended for tombs, and as evidently of a date coeval with the splendour of Persepolis.”

The rock-cut tombs and bas-reliefs at Naqsh-e Rostam were visited by several skilled French explorers and artists such as Charles Texier in 1835, and Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste during 1840-41. The descriptions and illustrations by the latter two are the most exceptional visual records predating the invention of photography. They even conducted excavations at the base of the Tower known as Ka’bah Zartosht to determine its height. Flandin’s concluding remarks on Naqsh-e Rōstam are worth mentioning here:

“Cet ensemble de grands et somptueux monuments de deux âges, ne peut laisser de doute sur l’importance qu’a eu ce lieu dans le passé. Les rois de deux dynasties qui ont jeté de l’éclat sur la Perse s’étaient plu, les unes, à y préparer leurs imposantes sépultures, les autres, à y buriner sur le roc impérissable les hauts faits de leur vie, afin d’en assurer le souvenir pour les siècles futurs.”

The first photographs of the monuments at Naqsh-Rōstam were taken by Luigi Pesce, an Italian infantry officer in the service of the Qajars, in 1858. In 1875, Franz Stolze took better photographs of the rock-cut tombs, the inscriptions on the Tomb of Darius, and Sasanian rock reliefs. A decade later, Marcel Dieulafoy visited the cliffside and took the first panoramic photograph of the cliffside and its monuments, which he published in his L’art antique de la Perse. His wife, Jane, described their visit to Naqsh-e Rōstam, and wrote that the followers of Zoroastrianism, in particular the Parsis of India, came to “visit in numerous pilgrimages the fire altars and the temporary tomb designated in the country under the name of the Ka’abeh of Zoroastrians.” In his Persia and the Persian Question published in 1892, George Curzon gives a comprehensive synthesis of all prior studies on Naqsh-e Rōstam up to his time. The 20th century saw a growth of interest in the systematic exploration of the Achaemenid and Sasanian remains in Fars, including those at Naqsh-e Rōstam. A thorough study of the monuments was published in 1910 by Friedrich Sarre and Ernst Herzfeld. Later, Herzfeld sounded a few areas in front of the cliffside in search of the site’s enclosure wall. He traced the exterior face of the presumably Sasanian mud-brick fortification which represents the principal mound deposit in front of the cliffside. He also uncovered part of a mud-brick building adjacent to the Tower. His successor, Erich Schmidt carried out large-scale excavations and cleared the entire area of the Tower, leading to the discovery of Shapur I’s inscription which was copied and translated by Martin Sprengling. Further readings were published by Walther Bruno Henning, Richard Frye, Michael Back, and Philip Huyse. Schmidt’s meticulous study of all the monuments at Naqsh-e Rōstam has since been the main reference for the archaeology of the site. More specialized studies of the bas-reliefs appeared later in the German series of Iranische Denkmäler in the 1970s and 1980s.

Finds

The excavated finds consist of remains of mud-brick structures in the vicinity of the Tower and the rest of the fortification lines of the site; potsherds, fragments of sculptures, fragments of glass, beads, and coins.

Bibliography

Back, M., Die sassanidischen Staatsinschriften, Acta Iranica 18, Leiden, 1978, pp. 279-486.

Canepa, M. P., “Technologies of Memory in Early Sasanian Iran: Achaemenid Sites and Sasanian Identity,” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 114, No. 4, 2010, pp. 563-596.

Chardin, J., Voyages de Monsieur le Chevalier Chardin en Perse et autres lieux de l’Orient, Amsterdam, 1711, vol. 3, pp. 121-126.

Chaumont, M. L., “L’inscription de Kartīr à la ‘Kaʿbah de Zoroastre’ (texte, traduction, commentaire),” Journal asiatique, vol. 248, 1960, pp. 339-380.

Curzon, G. N., Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 2, London, 1892, pp. 137-148.

Dieulafoy, J., La Perse, la Chaldée, et la Susiane, Paris, 1887, pp. 383-390.

Dieulafoy, M., L’art antique de la Perse, Paris, 1885, vol. 3, pp. 1-77, pls. I-III, V; vol. 5, pp. 113-135, pls. XIV-XVI.

Gignoux, Ph., Les quatres inscriptions du mage Kirdir: Textes et concordances, Studia Iranica cahiers 9, Paris, 1991, pp. 45-48.

Gropp, G., and S. Nadjmabadi, “Bericht uber eine Reise in West- und Südiran,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 3, 1970, p. 198, pl. 98/1-2.

Henning, W. B., “The Great Inscription of Shapur I [A.D. 241-272],” Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, vol. 9, No. 4, 1939, pp. 823-849.

Henning, W. B., The Inscription of Naqš-i Rustam, Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part 3, vol. II, Portfolio II, London, 1957.

Henning, W. B., Minor Inscriptions of Kartīr, together with the end of Naqš-i Rustam, Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part 3, Vol. II, Portfolio III, London, 1963.

Herbert, T., Some Years Travels into Divers Parts of Asia and Africa, London, 1638, pp. 146-147.

Herrmann, G., Naqhs-i Rustam 5 and 8. Sasanian Reliefs attributed to Hormuzd II and Narseh, Iranische Denkmäler, vol. 8, Iranische Felsrelief, Berlin, 1977.

Herrmann, G., D. N. Mackenzie, and R. Howell, The Sasanian Reliefs at Naqsh-i Rustam, Naqsh-i Rustam 6, The Triumph of Shapur I, Iranische Denkmäler 13, Berlin, 1989.

Herrmann, G. and V. S. Curtis, “Sasanian Rock Reliefs”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/sasanian-rock-reliefs-COM_186?s.num=5&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-iranica-online&s.q=Naqsh

Herzfeld, E., La sculpture rupestre de la Perse sassanide, Revue des Arts asiatiques, vol. 5, 1928, pp. 131-138.

Huff, D., “Fire Altars and Astodans,” in The Art and Archaeology of Ancient Persia: New Light on the Parthian and Sasanian Empires, edited by V. Sarkosh Curtis et al., London 1998, pp. 74-83.

Huyse, Ph., Die Dreisprachige Inschrift Šābuhrs I. an Der Ka’ba-i Zardušt (ŠKZ), Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part 3, Vol. I, Text I, in 2 vols., London, 1999.

Ker Porter, R., Travels, vol. 1, pp. 517-571, pls. 16-26.

MacKenzie, D. N., “Kerdir’s inscription,” The Sasanian Rock Reliefs at Naqsh-i Rustam. Naqsh-i Rustam 6, Iranische Denkmäler. Lief. 13. Reihe II: Iranische Felsreliefs I, Berlin, 1989, pp. 35-72.

Roaf, M., “Two Rock Carvings at Naqsh-i Rustam,” Iran, vol. 12, 1974, pp. 199-200.

Sarre, F. and E. Herzfeld, Iranische Felsereliefs, Berlin, 1910, pp. 67-91, pls. I-IV.

Schmidt, E. F., Persepolis, vol. 3, Chicago, pp. 5-76, 12-122, 127, 129, 134, 136.

Schmitt, R., The Old Persian Inscriptions of Naqsh-i Rustam and Persepolis, Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, Part I, vol. I. The Old Persian Inscriptions, Text II, London, 2000.

Schipmann, K., Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, Berlin, 1971, pp. 185-189.

Seidl, U., Die Elamischen Felsreliefs von Kūrāngūn und Naqš-e Rustam, Iranische Denkmäler 12, Berlin, 1986, pp. 14-19, fig. 2b, pls. 11-15.

Shapur Shahbazi, A., The Authoritative Guide to Naqsh-e Rostam, Tehran, 2015.

Skjærvø, P.O., “Kartir”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/kartir-COM_10867?s.num=155&s.rows=50&s.start=120

Sprengling, M., “A New Pahlavi Inscriptions”, American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 53, 1937, pp. 126-144.

Sprengling, M., Third Century Iran: Sapor and Kartir, Chicago, 1953, pp. 1-61 (for Naqsh-e Rōstam).

Stolze, F. and F. C. Andreas, Persepolis. Die Achaemenidischen und Sasanidischen Denkmäler und Inschriften von Persepolis, Istakhr, Pasargadae, Shâhpûr, Berlin, 1882, vol. 2, pls. 106-122.

Texier, Ch., Description de l’Arménie, la Perse et la Mésopotamie, vol. 2, Paris, 1842, pp. 198-200, pls. 127, 128, 135.

Vanden Berghe, L., Reliefs rupestres de l’Iran ancien, Bruxelles, 1985.

Von Gall, H., “Naqš-e Rostam,” Encyclopedia Iranica Online. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/naqs-e-rostam-COM_693?s.num=0&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-iranica-online&s.q=Naq%C5%A1-e+Rostam

Waele, E. de, “Nouvelles miettes de sculpture rupestre sassanide à Naqš-e Rostam,” Syria, vol. 54, 1977, pp. 65-88.

Wiesehöfer, J., “Engelbert Kaempfer und die Achaimenidischen Stätten von Naqš-i Rustam und Persepolis,” Achaemenid History VII. Through Travelers’ Eyes, Leiden, 1991, pp. 74-82.