Naqsh-e Rajabنقش رجب

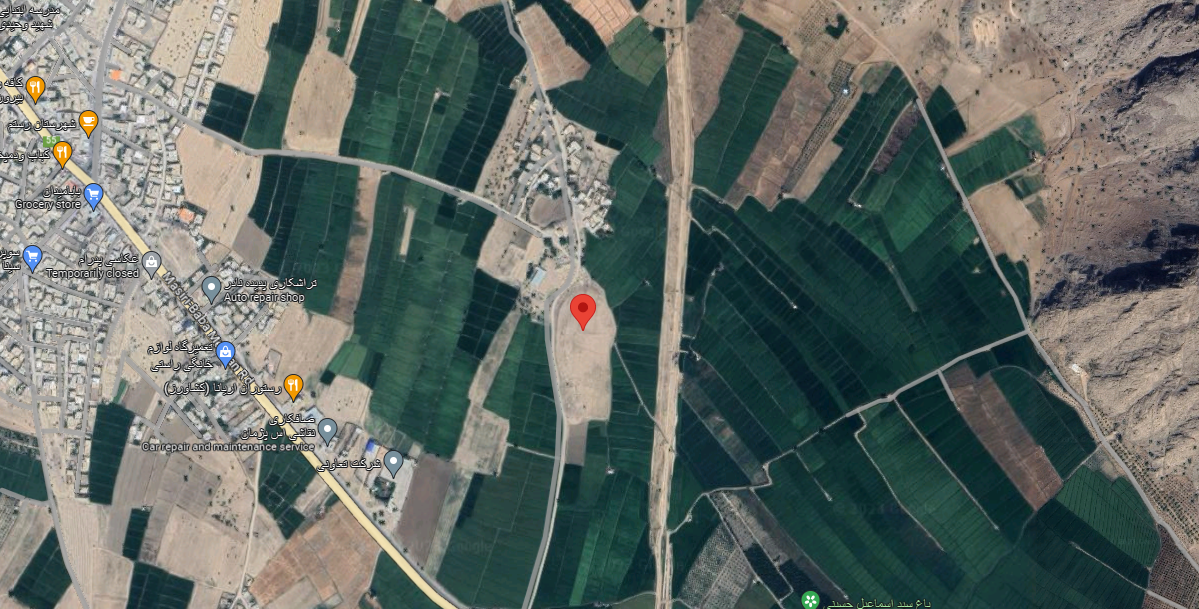

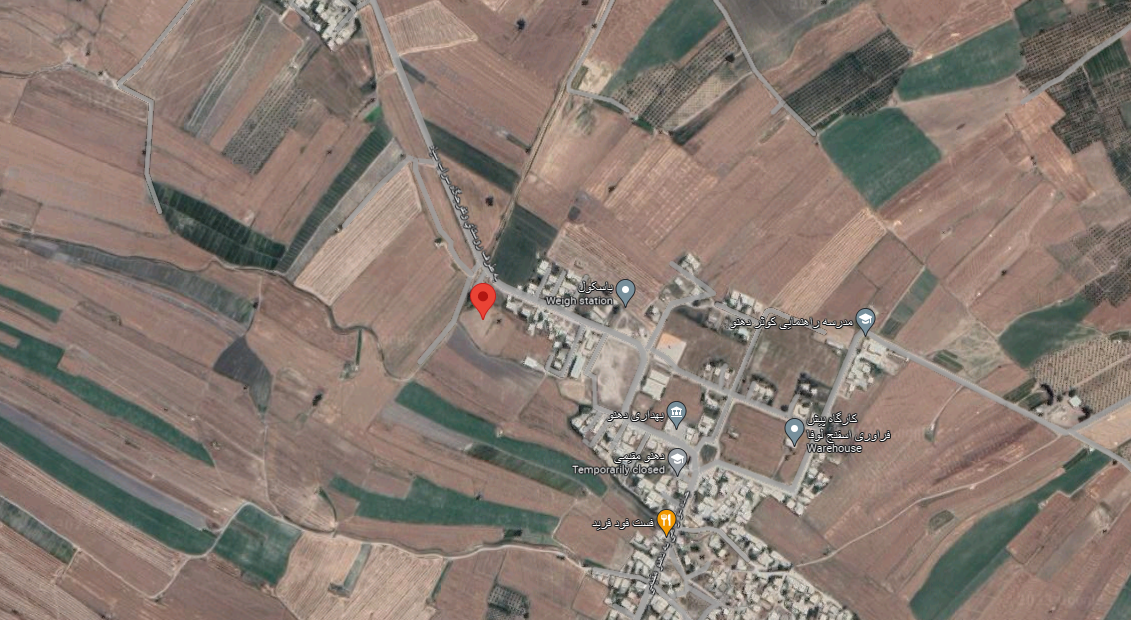

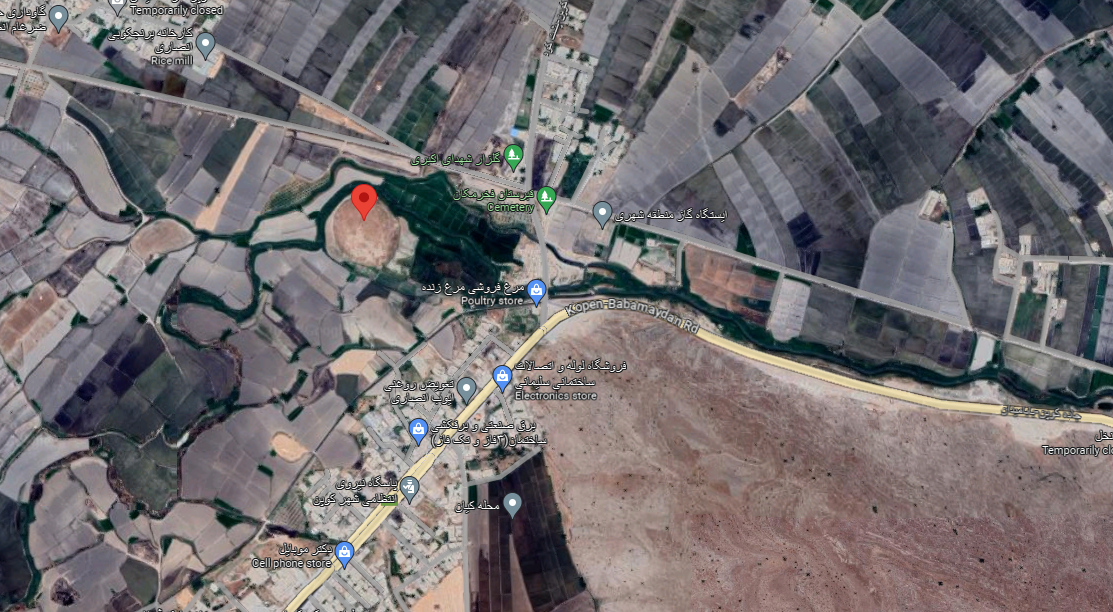

Location: Naqsh-e Rajab is in the vicinity of Persepolis, southern Iran, Fars Province.

29°57’59.2″N 52°53’13.8″E

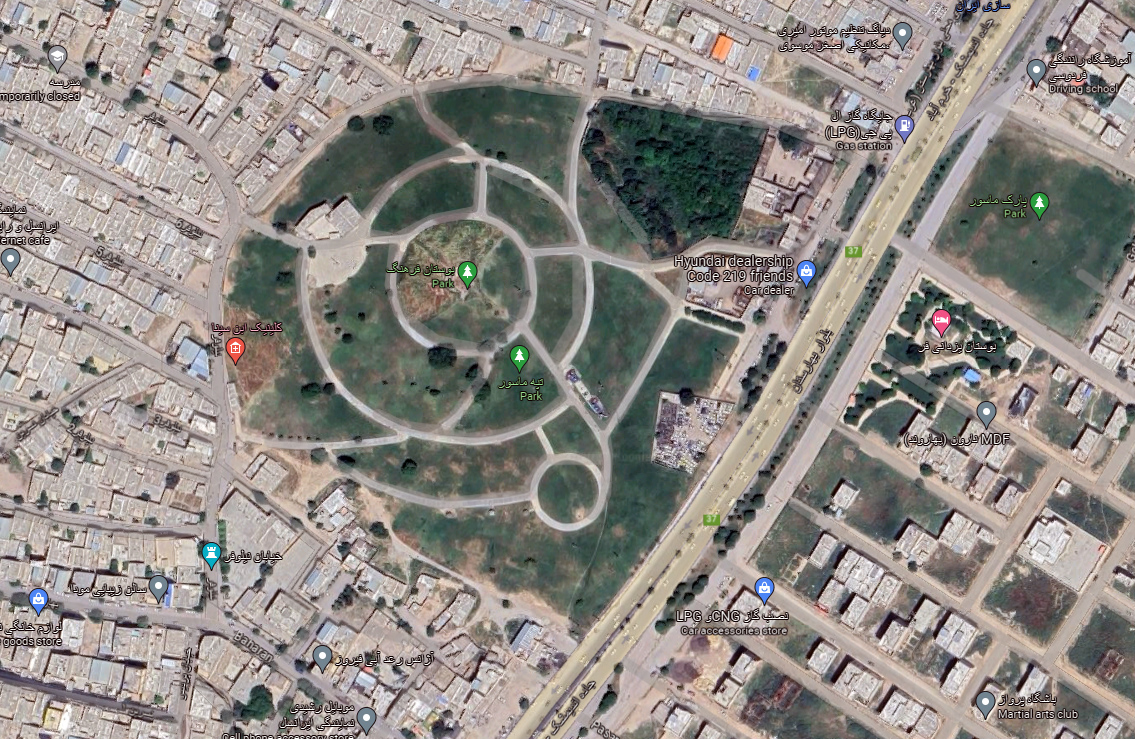

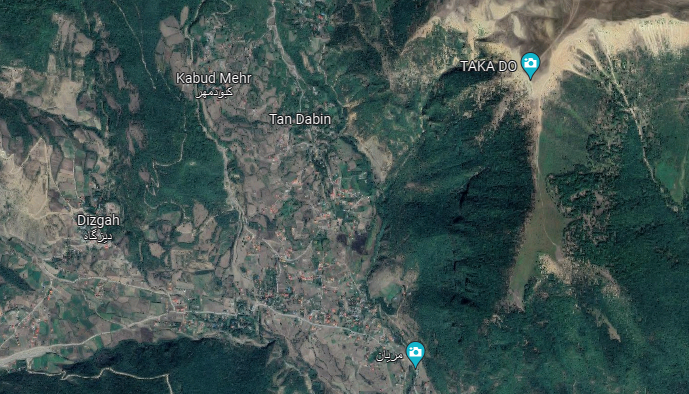

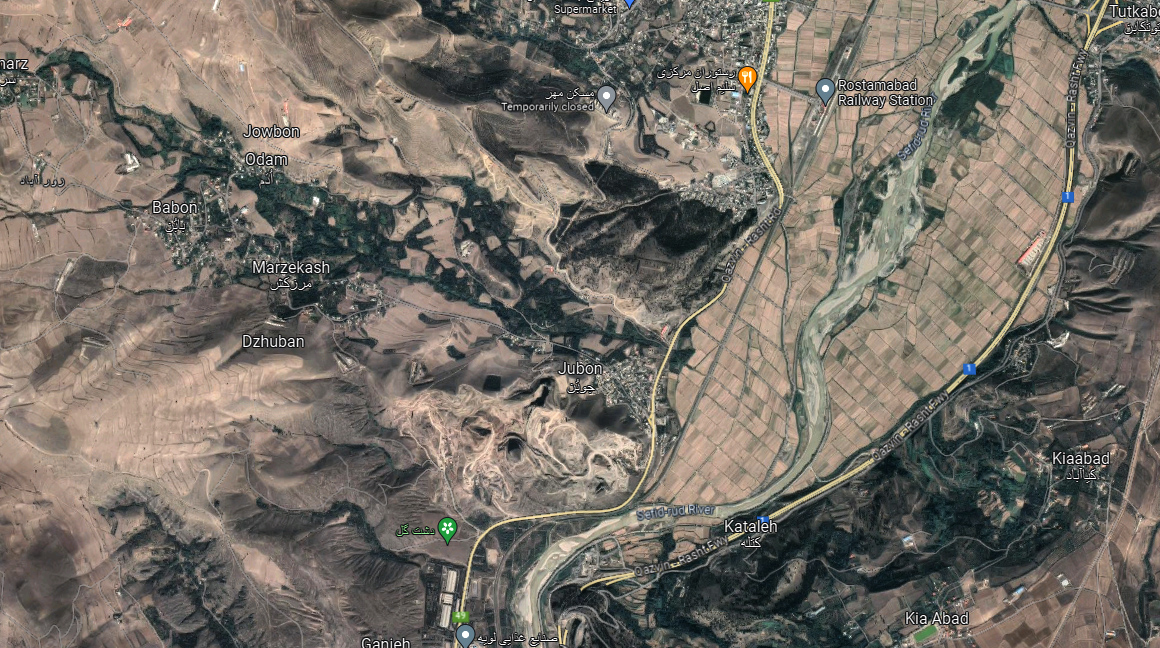

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian

History and description

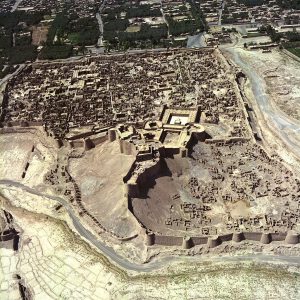

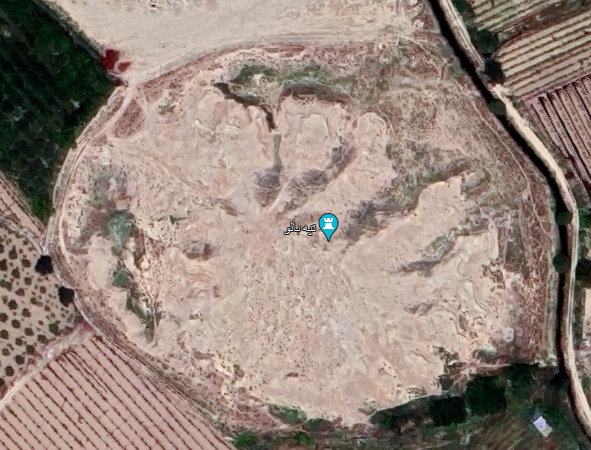

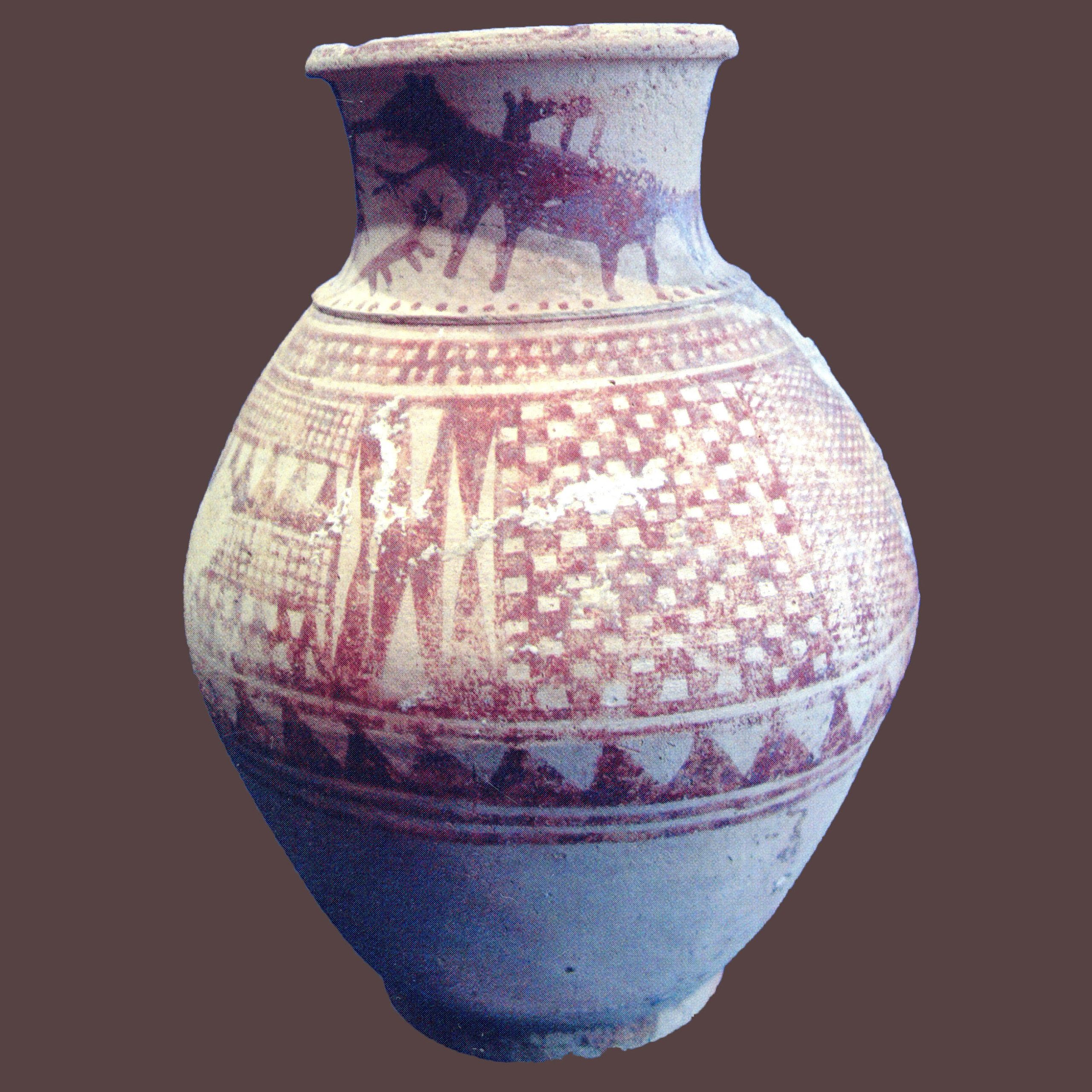

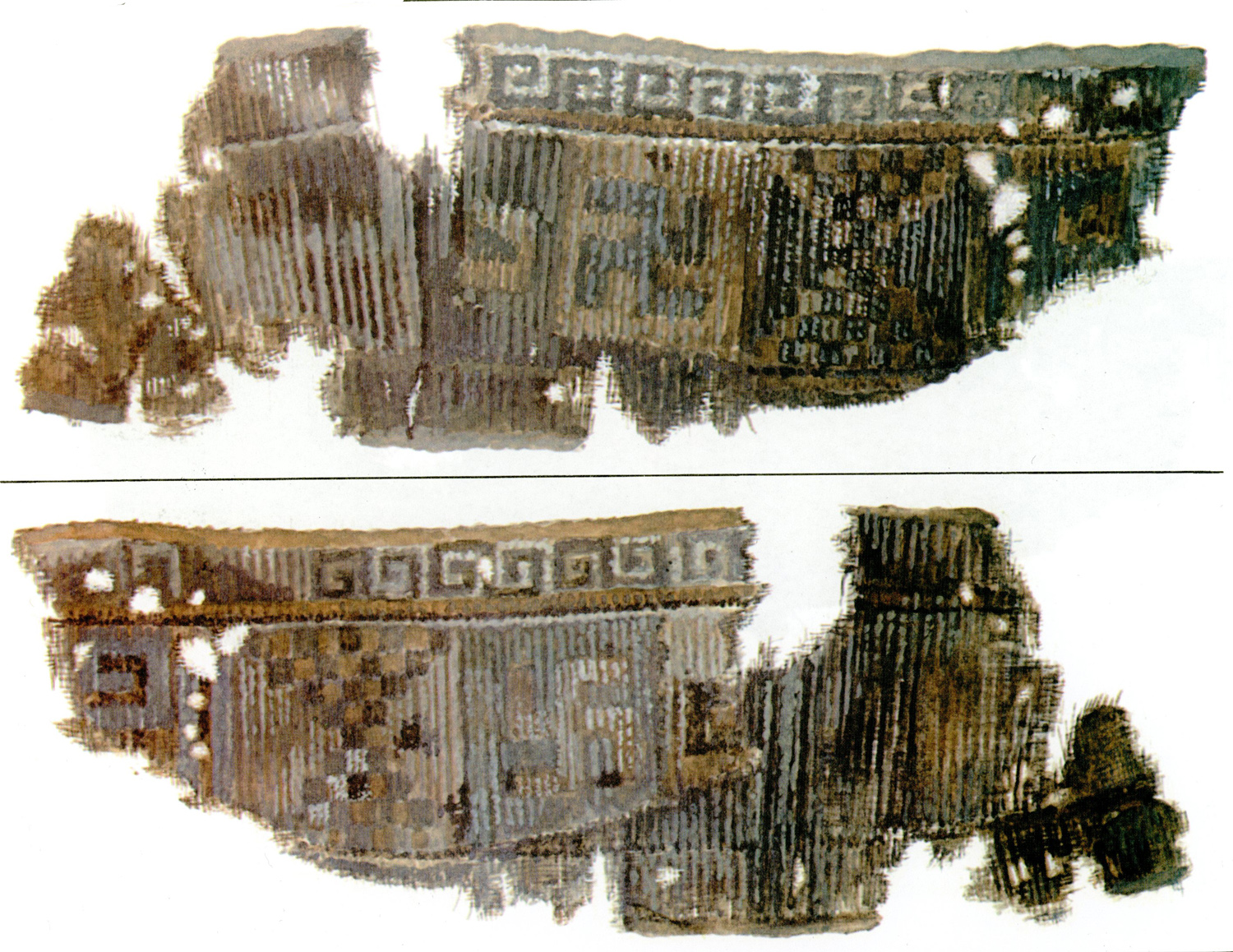

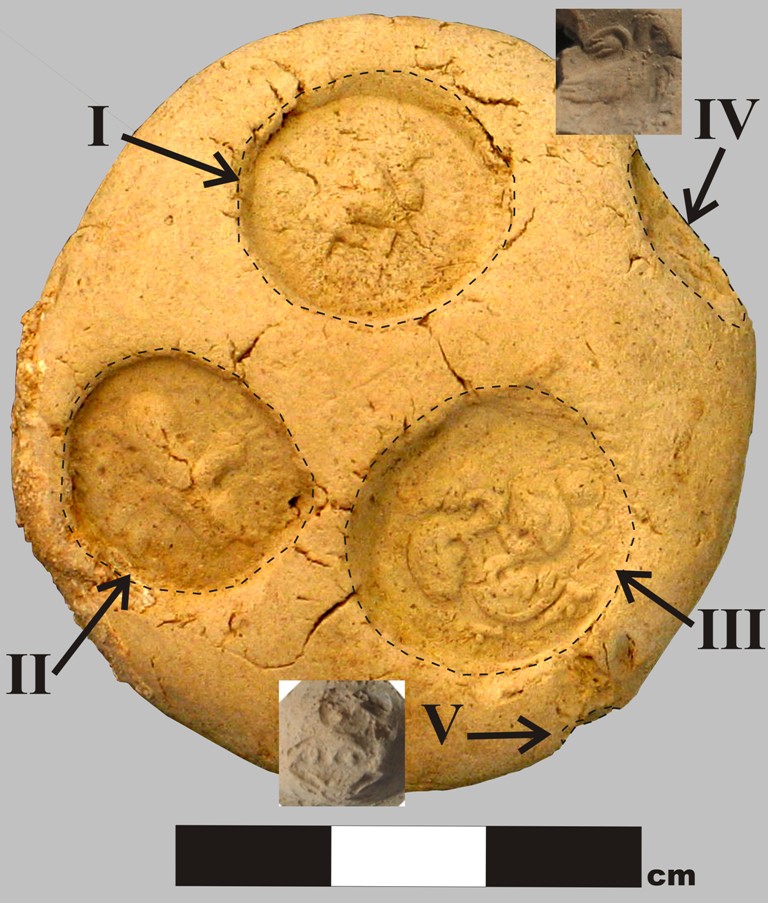

Naqsh-i Rajab is a rocky recess at the foot of the Kūh-e Rahmat, on the old Isfahan-Shiraz road (fig. 1). The site is 3.5 km north of Persepolis and about 3 km southeast of Naqsh-i Rustam as the crow flies. Four bas-reliefs are carved on three sides of the recess, the central location of which is occupied by the earliest that depicts an investiture scene of Ardashir I (fig. 2). The panel measures approximately 5 x 3 m. The king, represented in the right profile, wears a large globular hat or korymbos and receives the ring of power from the god. The god, whose head is depicted in the left profile, wears a mural crown or tiara of Achaemenid type. Between the two, there are two small figures interpreted as Ardashir’s grandsons. Behind the king are two figures that Schmidt identifies as the queen and the crown prince (Shapur?). Curiously, two attendants are shown behind the figure of the god. Scholars such as Herzfeld and Schmidt suggest that possibly a spring once emanated from the rocky nook, designating it as a sacred site—a sanctuary dedicated to Anahita, the goddess of waters and fertility. Ardashir’s grandfather, Sasan, and possibly his father Papak, held positions overseeing the Temple of Anahita at Istakhr, located just a few kilometers northwest of Naqsh-e Rajab. The site, located halfway between the mystical and highly respected ruins of Persepolis and Istakhr, was significant for the early Sasanian kings. This could be the reason why Ardashir chose Naqsh-e Rajab, presumed to be the shrine of Anahita, to commemorate his investiture. Sarre even believed that this investiture scene predated the larger one at Naqsh-e Rostam, a matter that is still debated.

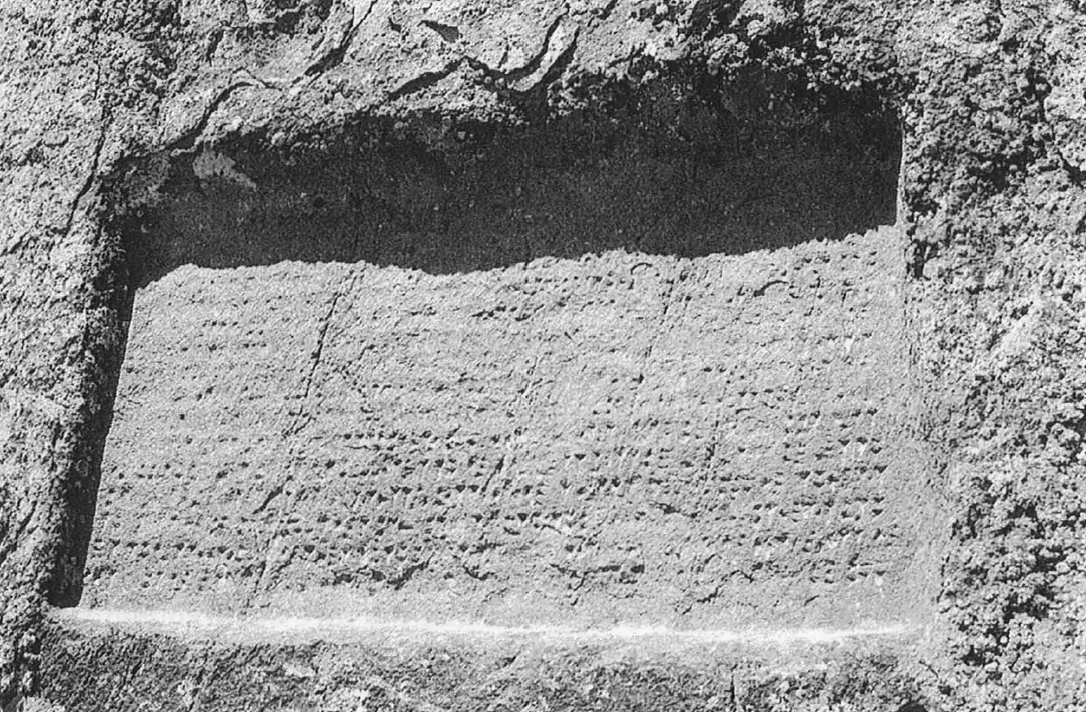

Adjacent to Ardashir’s investiture, there is the bust of the high priest Kartir (fig. 3) accompanied by his inscription, undoubtedly carved much later during the reign of Bahram II. Although the inscription does not refer to Ardashir, two of Kartir’s four rock-carved inscriptions mention that his career began during the rule of the Sasanian Empire's founder, which could potentially explain the placement of Kartir's Naqsh-e Rajab portrait.

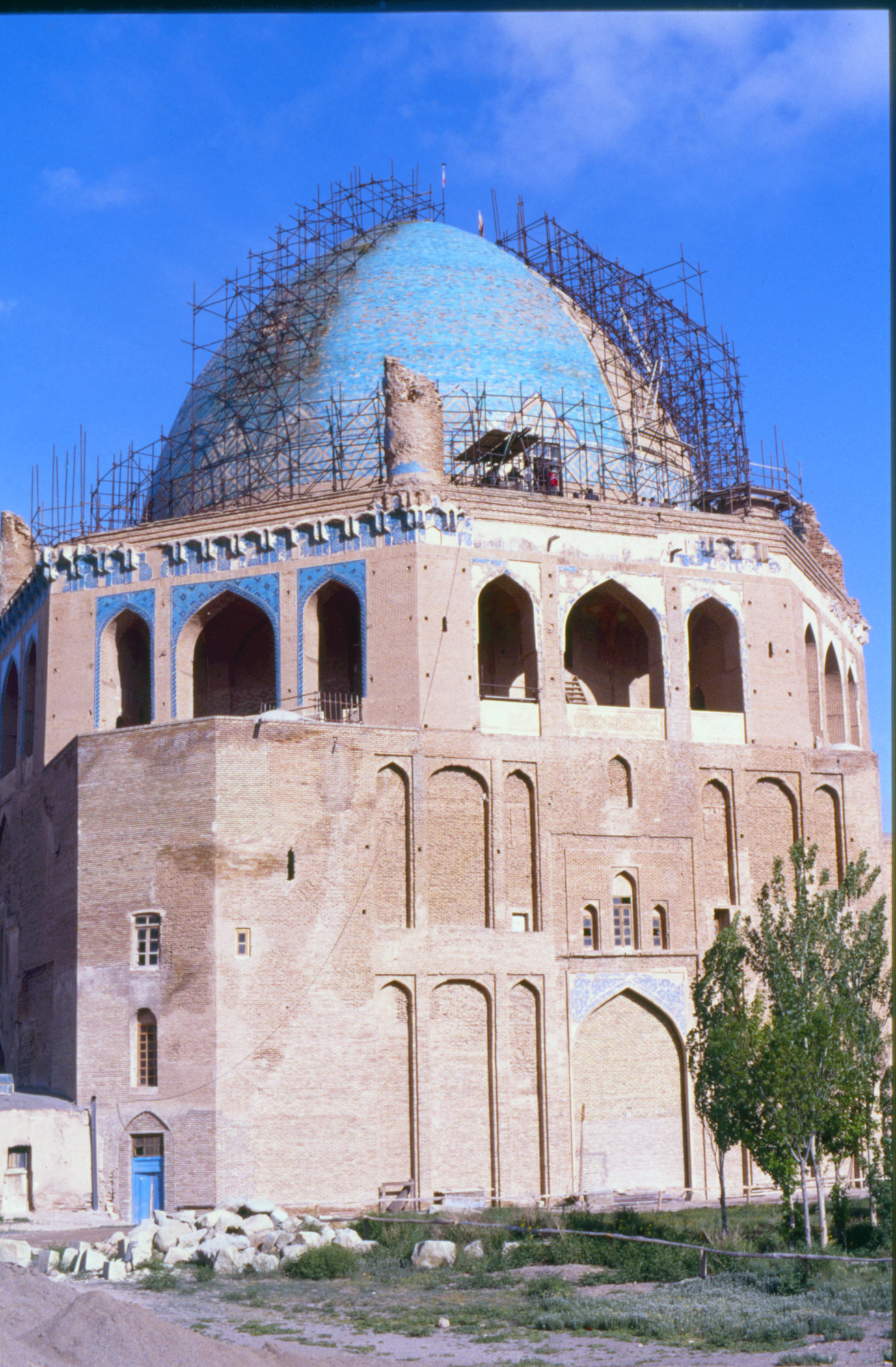

The equestrian investiture of Shapur I occupies a large panel that measures 6.40 x 2.90 m (fig. 4). The king is depicted receiving the ring of power from his god. The scene resembles the other investiture scene of Shapur I at Tang-e Chowgān, near Bishāpūr. However, due to the limited space, prostrate Romans or enemies are omitted.

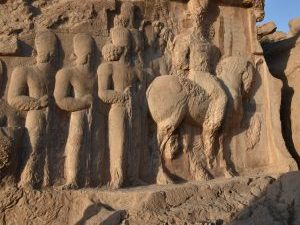

Shapur's second relief occupies the largest panel and measures 7 x 4 m (fig. 5). It represents the king on horseback followed by nine individuals. An inscription identifies the king as Shapur I.

1. Naqsh-e Rajab. View of the recess from the west (image: Carole Raddato, www.followinghadrian.com, CreativeCommons)

2. Naqsh-e Rajab. The Investiture of Ardashir (image: Sasha India, Creative Commons)

3. Naqsh-e Rajab. Rock-relief and inscription of Kartir (image: Carole Raddato, www.followinghadrian.com, CreativeCommons)

4. Naqsh-e Rajab. The investiture of Shapur I (image: Carole Raddato, www.followinghadrian.com, CreativeCommons)

5. Naqsh-e Rajab. Shapur I and his entourage (image: Omid Javidani, CreativeCommons)

Archaeological Exploration

The first European traveler who recorded the presence of rock reliefs at Naqsh-e Rajab was Carsten Niebuhr. During his stay at Persepolis in 1765, he copied and published a combined engraving of two scenes: the Investiture of Ardashir and Shapur I and his entourage. Then, the reliefs were visited and briefly described by the British James Morier and William Ouseley in the early years of the 19th century. In 1839, Charles Texier visited the site and drew the first accurate pictures of two of the four scenes. He rightly identified the portrait of Ardashir on his investiture scene. Two other French artists, Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste, described the site and its rock reliefs and produced far better views of the monuments, which they published in 1853. Photographs of the bas-reliefs were taken later by Franz Stolze in 1877, and Marcel Dieulafoy in 1881. In the late years of that century, two important contributions are worth mentioning: Forasat Shirazi’s description and drawings in his Āsar-e Ajam, and George Curzon’s critical review of his predecessors' work on the study of the bas-reliefs. A thorough study of the bas-reliefs began by Friedrich Sarre and Ernst Herzfeld in their Irasnische Felsreliefs, and was elaborated later with far better pictures and systematic description and discussion by Erich Schmidt.

Bibliography

Curzon, G. N., Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 2, pp. 126-128.

Dieulafoy, M., L’art antique de la Perse, vol. 5, Paris, 1895, pl. 17.

Flandin, E. and P. Coste, Voyage en Perse, Paris, 1843-1854, text: pp. 151-154; plates: vol. 4, pls. 189-192.

Frye, R. N., “The Middle Persian Inscription of Kartīr at Naqš-i Rajab,” Indo-Iranian Journal, vol. 8, No. 3, 1964, pp. 211-225.

Herzfeld, E., “La sculpture rupestre de la Perse sassanide,” Revue des arts asiatiques, vol. 5, 1928, pp. 130-132, figs. 2 and 5, pls. 35 and 37.

Herzfeld, E., Iran in the Ancient East, London, 1941, pp. 311-314, pls. 57, 60, 62.

Hinz, W., Die Felsreliefs Ardashirs I, Alitiranische Funde und Forschungen, Berlin, 1969, pp. 123-126, pls. 57-59.

Hinz, W., Karders Felsbildnesse, Alitiranische Funde und Forschungen, Berlin, 1969, p. 191, pls. 113-114.

Morier, J., A Journey Through Persia Armenia Asia Minor, London, 1812, pp. 137-139, pls. 19-20.

Niebuhr, C., Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern, Copenhagen, vol. 2, 1778, p. 153, pl. 132.

Ouseley, W., Travels in Various Countries of the East, vol. 2, pp. 291-293, pl. 49.

Sarre, F. and E. Herzfeld, Irasnische Felsreliefs, Berlin, 1910, pp. 92-97, pls. 11, 12, 13.

Schmidt, E. F., Persepolis, vol. 3, pp. 123, 125, 131, pls. 96-101.

Skjærvø, P.O., “Kartir”, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/kartir-COM_10867?s.num=155&s.rows=50&s.start=120

Sprengling, M., Third Century Iran: Sapor and Kartir, Chicago, 1953, pp. 63-68 (for Naqsh-e Rajab).

Texier, Ch., Description de l’Arménie et de la Perse, vol. 2, Paris, 1852, pp. 230-231, pls. 139-141.

Trümpelmann, L., “Šapūr mit der Adlerkopfkappe,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 4, 1971, pp. 173-185, pl. 27.

Vanden Berghe, L., Reliefs rupestres de l’Iran ancien, Brussels, 1984, pp. 64, 69, 76, 128, 140, pls., 20, 31.