Kharga Oasis / Hibisالخارجه / هیبیس

Location: Kharga Oasis is located in Egypt’s Western Desert, approximately 200 km west of the Nile Valley.

25°26’18.0″N 30°33’30.0″E

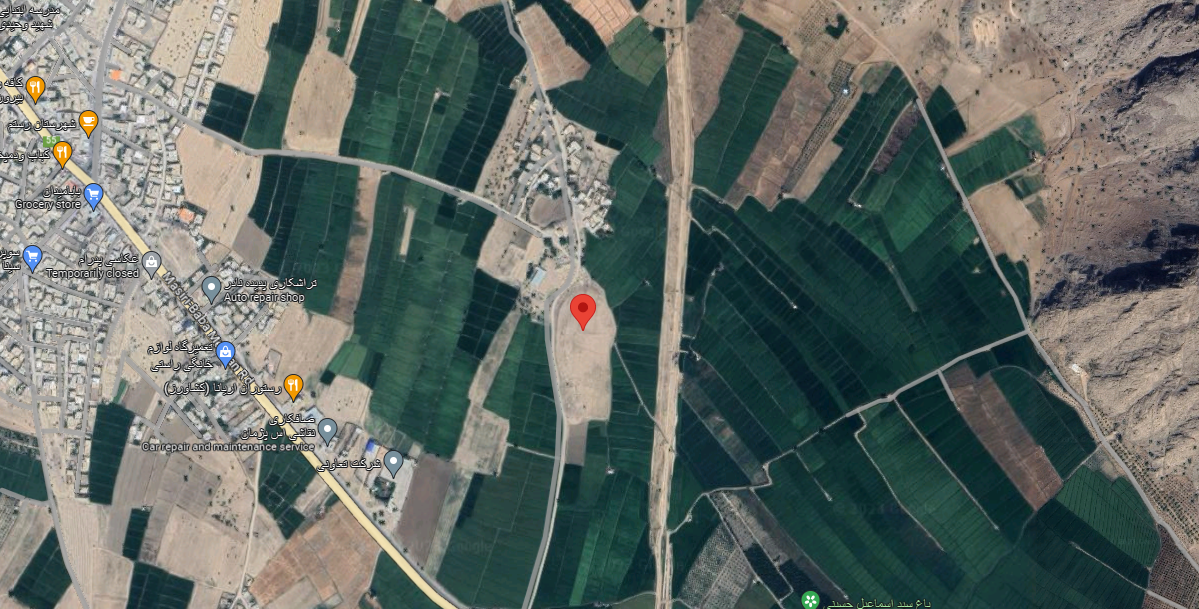

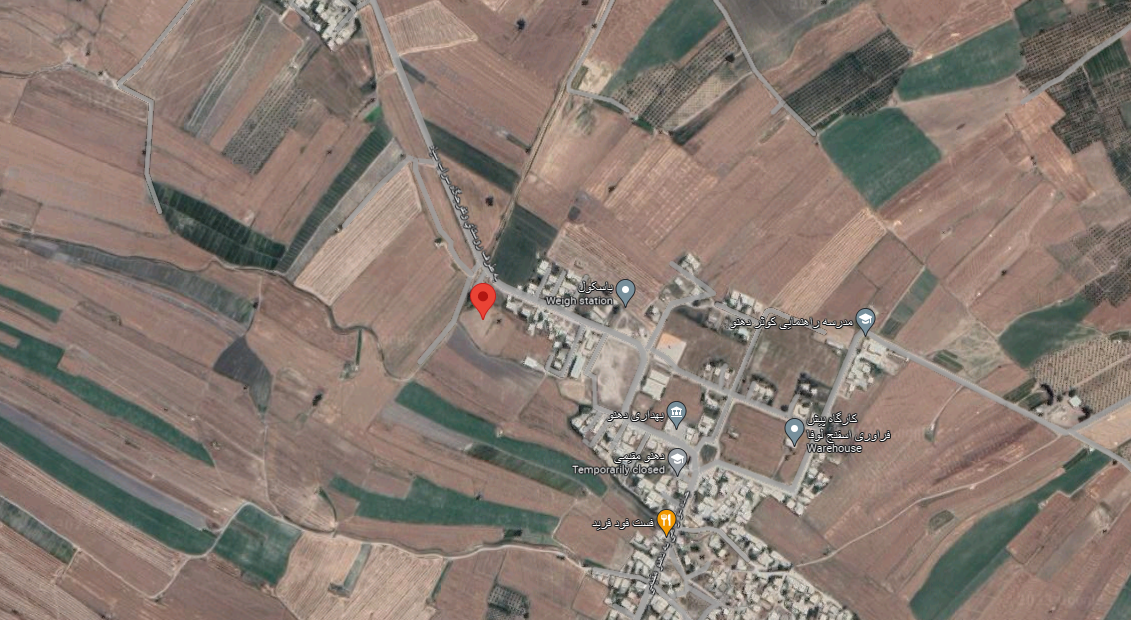

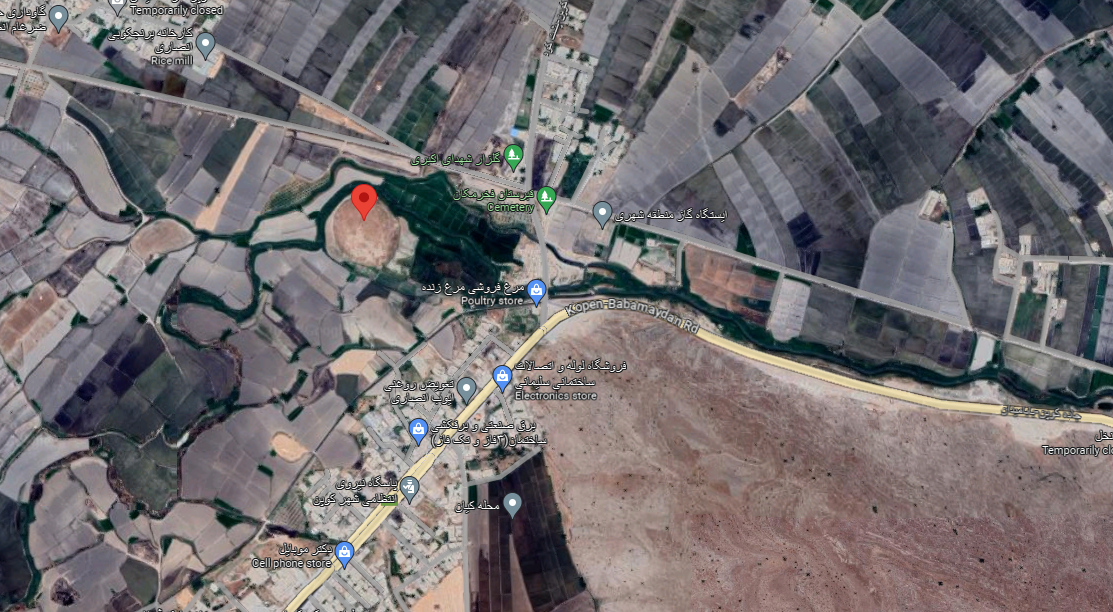

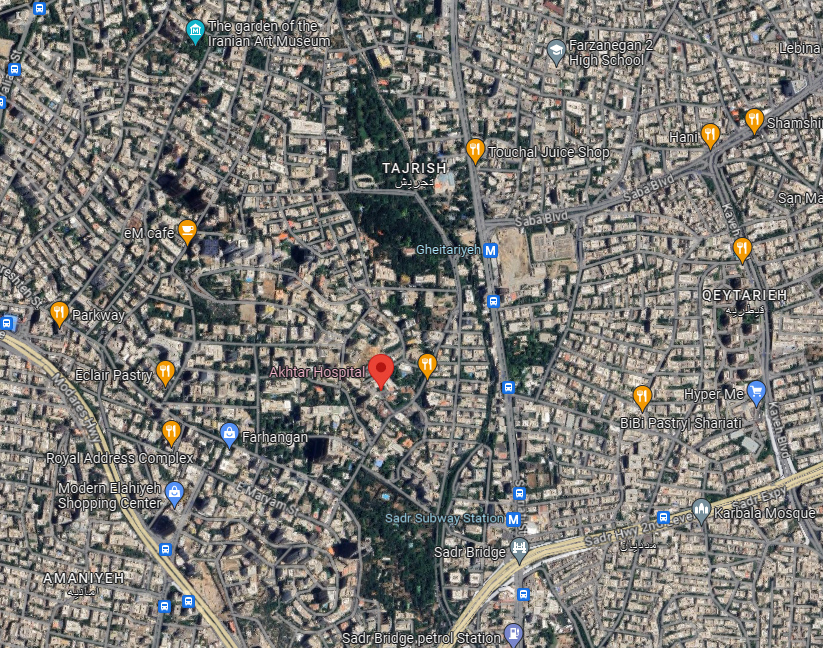

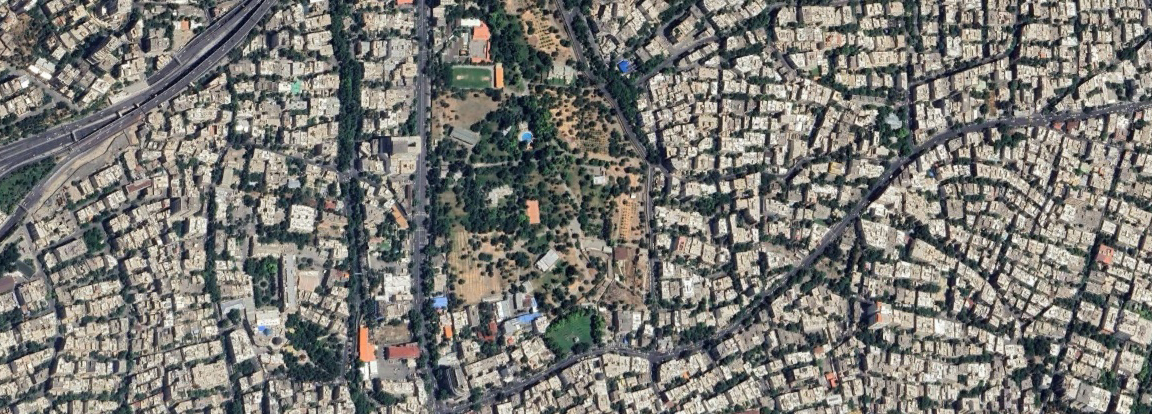

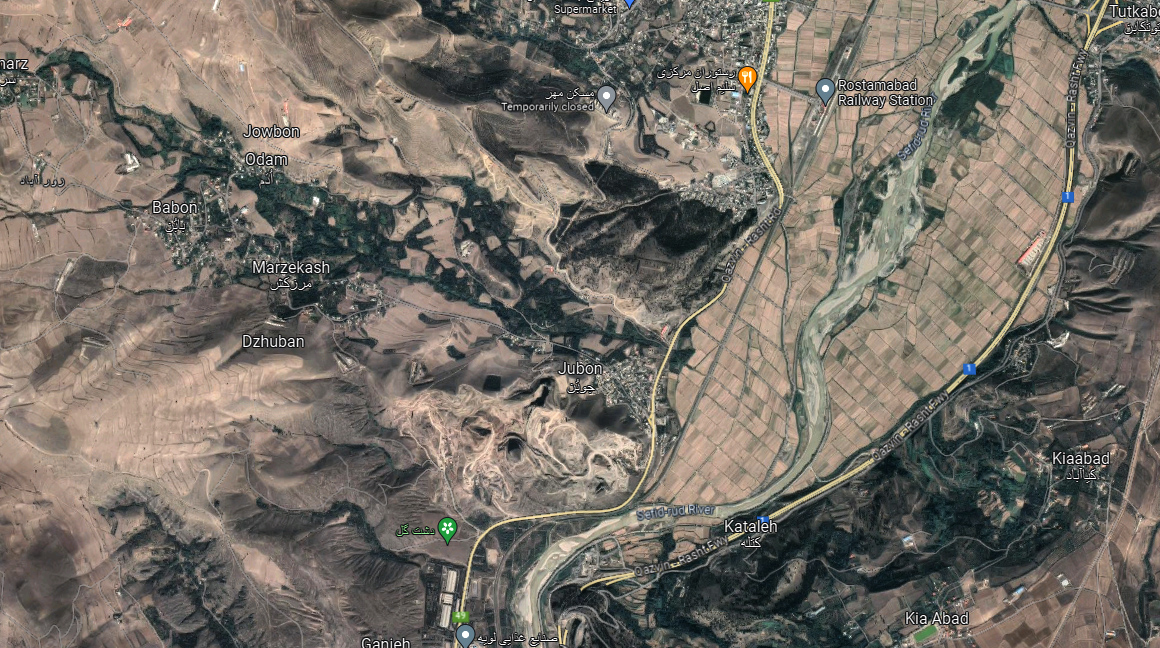

Map

Historical Period

Achaemenid

History and description

The oasis, which was known as the “Southern Oasis of Hibis” to the ancient Egyptians, the “Outer (he Exotero) Oasis” to the Greeks, and “Oasis Magna” to the Romans, is the largest of the five major oases in the Libyan desert of Egypt and the one that extends furthest south. It is in a depression about 160 km long and from 20 km to 80 km wide. In antiquity, it was the location of a junction of desert roads connecting the oases and points along the Nile Valley.

Hydraulically sustained by a qanāt system, the Kharga Oasis contains Achaemenid monumental constructions that offer key insights into how Persian rulers interpreted Egyptian religion. At least three temples in Kharga can be securely dated to the 27th Dynasty. Additional temples may also have been constructed during this period; however, later modifications during the Ptolemaic or Roman periods make definitive dating difficult without further evidence.

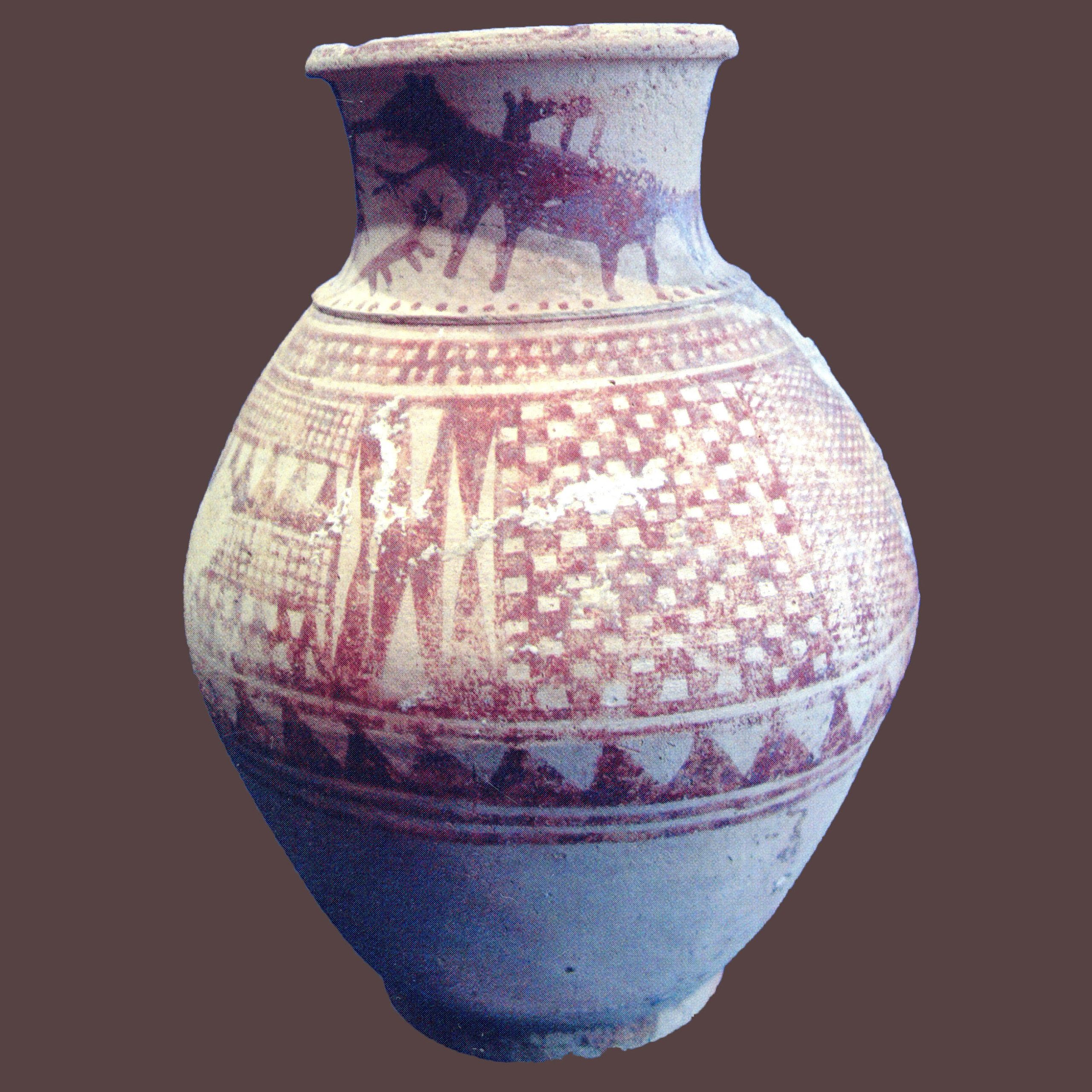

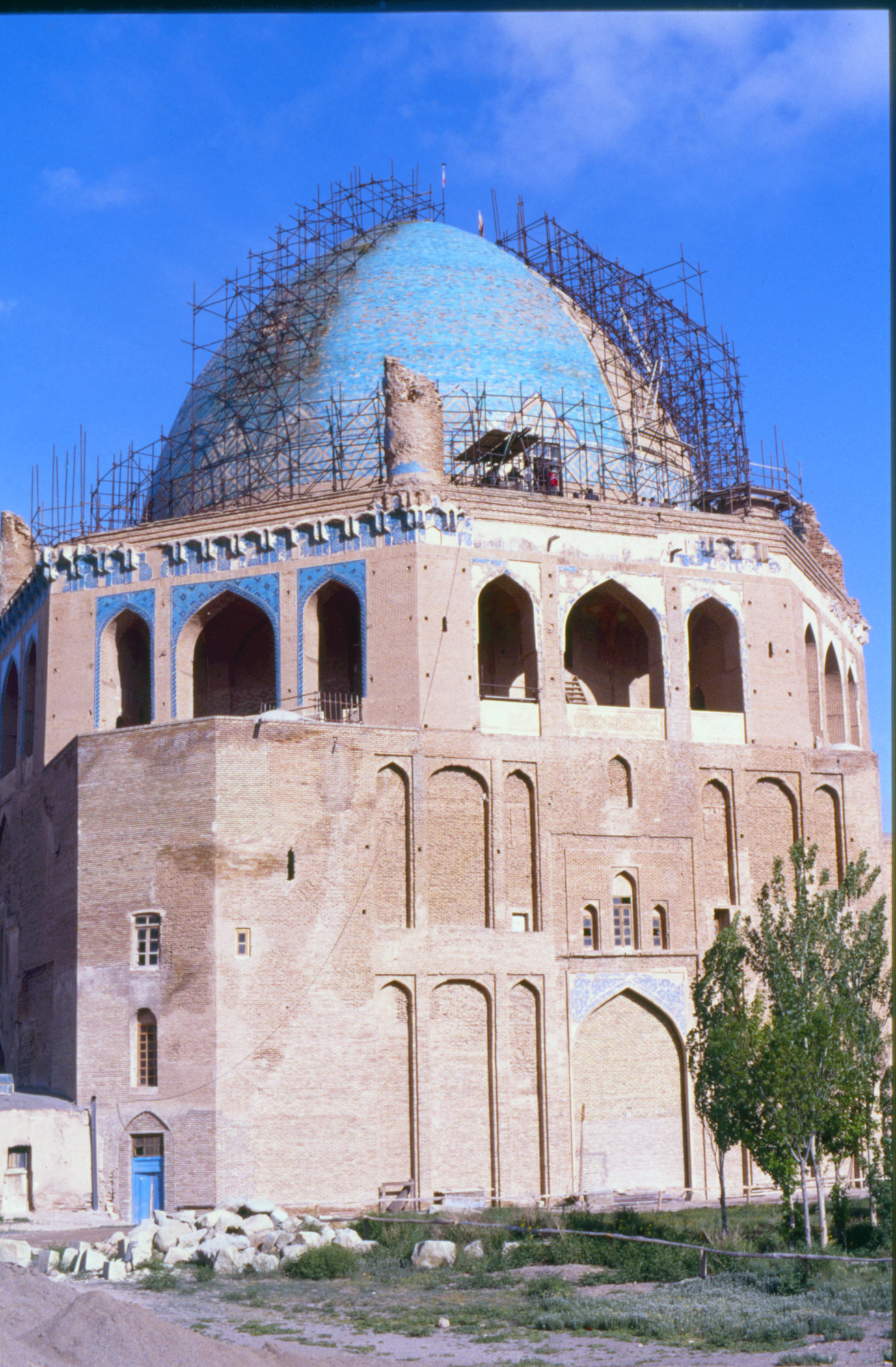

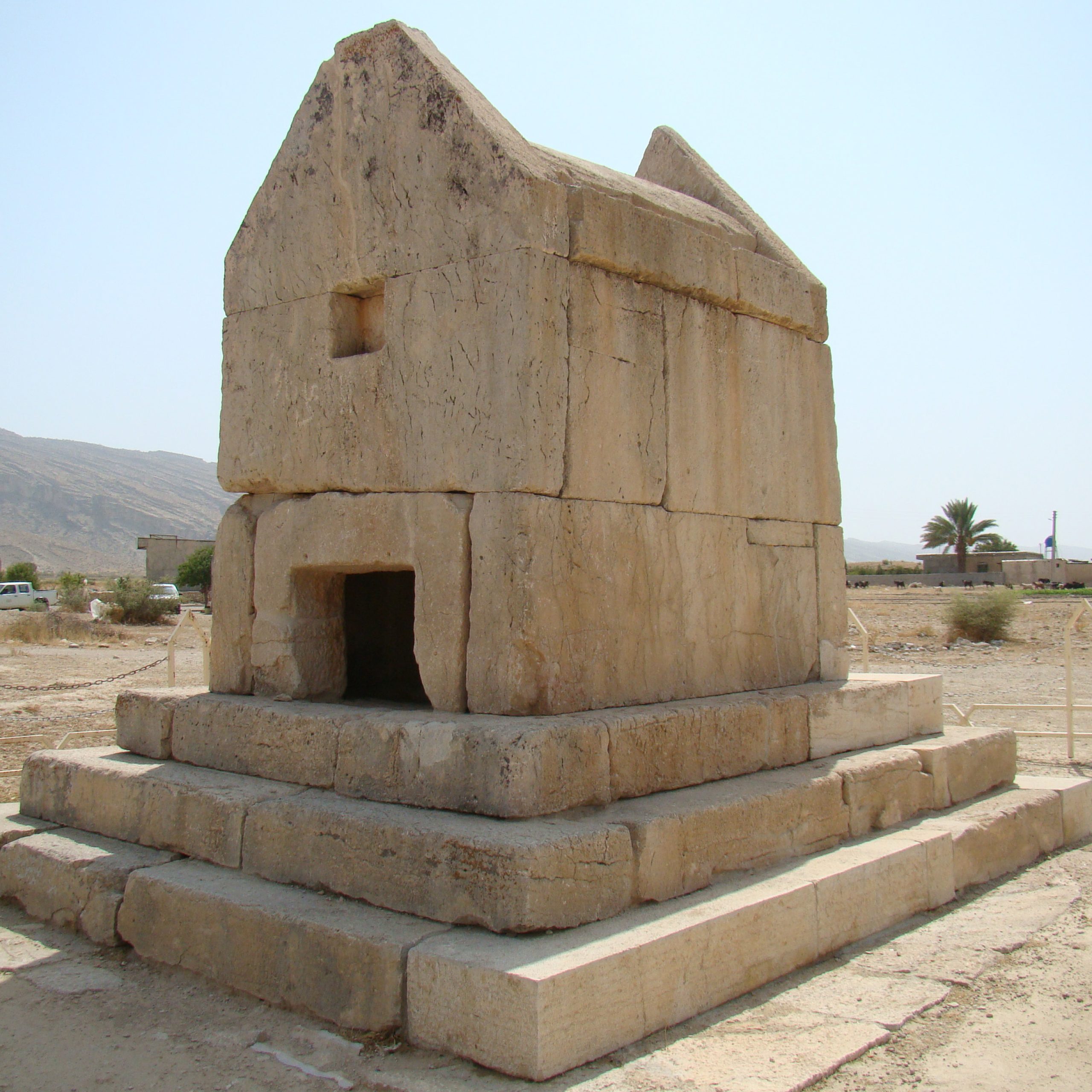

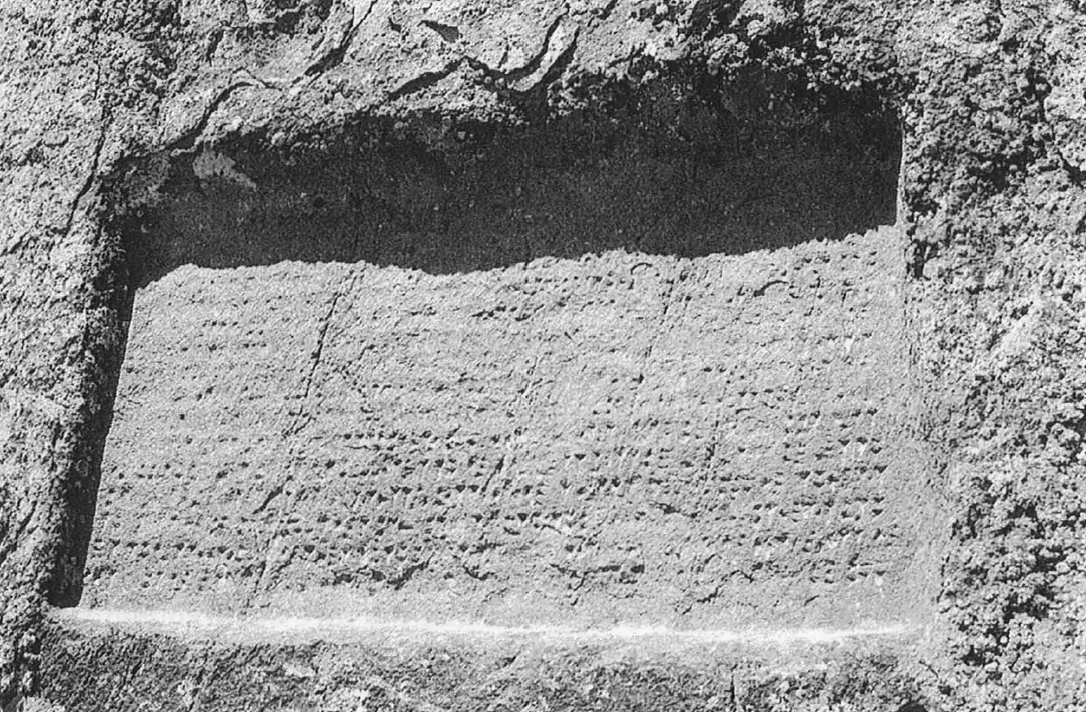

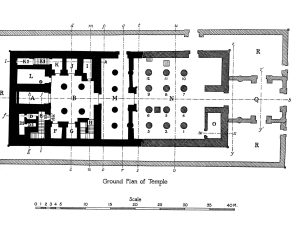

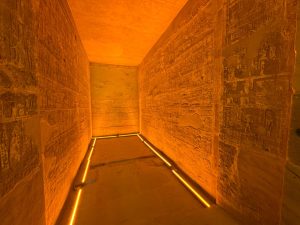

The Temple of Amun in Hibis is the largest and best-preserved temple in the Kharga Oasis (Fig. 1). The existing Temple of Hibis was constructed over several different periods, with the western half of the monument being the earliest, erected during the Achaemenid period. Built in sandstone, the temple is 45 m long and 19 m wide (fig. 2). It consists of an entrance portico (Q) on the east side, a large hypostyle hall (N) (fig. 3), the Old Temple (M), and a four-columned hall leading (B) to the sanctuary (A) (fig. 4).

The entire front width of the temple built under Darius I was taken up by columned hall M, which at the time served as an entrance porch. It originally featured two rows of columns, one forming a screen that temporarily served as the temple’s façade, and another set positioned inside. The walls bear decorations featuring scenes that depict Darius offering gifts to, and receiving greetings from, various deities (fig. 5).

The exterior walls of the temple are first decorated during the reign of Darius I, but there is debate as to whether the foundations and initial construction date back to the 26th Dynasty. There are scenes depicting Darius offering to Egyptian deities (figs. 6 and 7) and as an Egyptian Pharaoh on the temple’s exterior wall, wearing the Double Crown (fig. 8). If originally a Saite construction, the temple would most likely date to the reign of Psamtik II. Be as it may, it seems very likely that an earlier New Kingdom temple stood on the site before the construction of the Saite/Persian temple that survives today.

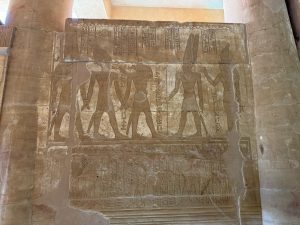

Other notable reliefs of the temple include previously unprecedented representations of approximately 700 gods from throughout Egypt in the sanctuary (fig. 9). The 700 deities are grouped geographically, demonstrating a detailed knowledge of Egyptian religion by either the artists, temple commissioners, or both, and overwhelmingly represent the deities of Upper Egypt, with those of Lower Egypt being mostly excluded. Inside the Temple of Darius, there is a large scene depicting a falcon-headed Seth spearing Apophis (fig. 10).

As Erich Schmidt rightly observes, when comparing the plan of Darius’ temple at Hibis in Egypt with his palace at Persepolis (Tacharā), notable similarities emerge. Both have a portico—an entrance porch at Hibis and a columned portico at Persepolis—leading into a central hypostyle hall surrounded on three sides by rooms. At Hibis, these rooms are chapels and sanctuaries, while at Persepolis, they are royal living quarters. The temple’s cavetto cornices also reflect Egyptian influence seen in Persian buildings, such as Egyptianized lintels frequently used in Achaemenid monumental architecture.

Fig. 1. The Hibis Temple (image R. Rollinger).

Fig. 2. Plan of the Temple of Amun at Hibis (after Winlock, The Temple of Hibis in El Khārgeh Oasis, vol. 1, pl. 32).

Fig. 3. The Hibis Temple. Interior of the hypostal hall (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 4. Inner sanctuary of the Hibis Temple (image: R. Rollinger).

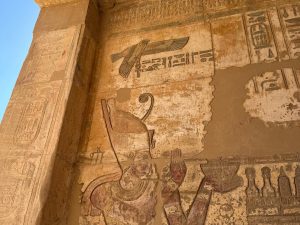

Fig. 5. Darius, kneeling, offers wine to Osiris, Horus Son of Isis, Isis, and Nephthys. South reveal of the gateway to Darius’ Temple (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 6. Darius wearing the Double Crown offering lettuces to the god Amun-Min-Kamutef on the interior wall of the Inner Gateway. The cartouche of Darius is carved on the left side, on the jamb (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 7. South wall, upper register. Darius (center), wearing the White Crown, runs with cramp and flail toward the goddess Meret, standing on the House of Gold. Behind Meret stands Amun-Reh of Hibis (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 8. Darius “being led to the sanctuary” by Up-wawet of the south and Khnum into a hall to be received by Amenebis and Udo, who “give him all lands.” South jamb of the gateway to Darius’ Temple (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 9. Part of the scene depicting 700 deities at Hibis Temple (image: R. Rollinger).

Fig. 10: Seth as a winged, falcon-headed deity spearing Apophis, on the north façade of the Darius Temple (image: R. Rollinger).

Archaeological Exploration

The first archaeological explorations and epigraphic surveys of Hibis Temple and the surrounding area were conducted in 1909-1913 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and published by Herbert Winlock in 1941. Harry Burton (famous for his photography of the excavation of the tomb of Tutankhamun) took photographs of the temple in 1924, and Norman de Garis Davies made multiple trips to Kharga Oasis from 1926 to 1939 to copy the reliefs of the temple.

In the 1980’s Eugene Cruz-Uribe studied the temple as the director of the Hibis Temple Project. His publications provide a partial translation, commentary, discussion, and sign list of the temple and the Demotic graffiti of Gebel Teir. He wrote, “I intended this volume to be a number of things and for it not to be a number of things. What it is not is the last word on the Hibis Temple. The work thus far has demonstrated to me that a complete understanding of all aspects of Hibis Temple will not come soon, but only after many years of systematic research and discussion. To that end, this volume is the first step.” More recently, Fatma Talaat Ismail has continued Cruz-Uribe’s work and provided a more comprehensive analysis of the decoration of the temple’s cult chapels.

John Darnell, director of the Theban Desert Road Survey, has studied the intricate desert road system that links the Kharga Oasis to the other western oases and the Nile Valley.

Larger surveys undertaken include the North Kharga Oasis Survey (NKOS), which in 2018 presented the results of their archaeological exploration carried out over seven years in the northern part of Kharga Oasis. This area had seen limited archaeological exploration until 2001, when NKOS was founded by co-directors Carla Rossi and Salima Ikram. As stated in the publication and project description, “NKOS has discovered and documented sites dating to all eras, ranging from the Prehistoric to the Late Antique. They include temporary camps, rock art sites, settlements, tombs, temples, industrial areas, Roman forts, fields, complex irrigation systems, and a network of routes that connect the sites, as well as linking Kharga to the Nile Valley, Dakhla Oasis, Sudan, and beyond. The distribution, types of sites, and water acquisition strategies illustrate the changing interactions between humans and the landscape, which has fluctuated between wet and dry over time” (Rossi and Ikram, North Kharga Oasis Survey).

Finds

Human remains from three cemeteries in the Kharga Oasis have been excavated and studied. The Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale excavated at Dush (1981-1993), and the Alpha-Necropolis team and the Supreme Council of Antiquities worked at Ain el-Labkha (1994-1997) and El-Deir (1998-2019). Over 1,000 individuals were studied by Jean-Louis Heim, who led the anthropological study of human remains, and Roger Lichtenberg, who led the pathological and radiological studies. The project was directed by Françoise Dunand.

Hundreds of Demotic ostraca have been discovered in Kharga Oasis, most from the Persian period. Those from the sites of El-Deir, Qasr el-Zayyan, Tell Dush, Ain Manawir, and Ain Ziyada, excavated in the past forty years, were studied by Damien Agut-Labordère.

The pottery assemblage from El-Deir in the Kharga Oasis has most recently been studied by the Partner University Fund Oasis Magna Project, led by Pascale Ballet.

Bibliography

Arnold, D., Temples of the Last Pharaohs, New York, 1999.

Bagnall, R. and G. Tallet, The Great Oasis of Egypt, New York, 2019.

Colburn, H., Archaeology of Empire in Achaemenid Egypt, Edinburgh Studies in Ancient Persia, Edinburgh, 2020.

Cruz-Uribe, E., Hibis Temple Project Volume 1: Translations, Commentary, Discussions, and Sign List, San Antonio, Texas, 1988.

Cruz-Uribe, E., Hibis Temple Project Volume 2: The Demotic Graffiti of Gebel Teir, San Antonio, Texas, 1995.

Cruz-Uribe, E., “Kharga Oasis, Late period and Graeco-Roman sites,” In Encyclopedia of Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, edited by K. Bard, London and New York, 1999, pp. 406-408.

Cruz-Uribe, E., “The foundations of Hibis,” In Servant of Mut: Studies in Honor of Richard A. Fazzini, edited by S. D’Auria, Leiden; Boston, 2008, pp. 73-82.

Darnell, J., Egypt and the Desert, Cambridge Elements of Ancient Egypt in Context, New York, 2021.

Davies, Norman de Garis, The Temple of Hibis in El Khārgeh Oasis, vol. III: The Decoration, New York, 1953.

Dunand, F., B.A. Ibrahim and R. Lichtenberg, Le matériel archéologique et les restes humains de la nécropole de Dabashiya (oasis de Kharga), Montpellier, 2012.

Ismail, F. T., Cult and Ritual in Persian Period Egypt: An Analysis of the Decoration of the Cult Chapels of the Temple of Hibis at Kharga Oasis, Yale Egyptological Studies 13, New Haven, 2019.

Kuhrt, A., The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, New York, 2007.

Newton, C., T. Whitbread, D. Agut-Labordère, and M. Wuttman, “L’agriculture oasienne à l’époque perse dans le sud de l’Oasis de Kharga (Égypte, Ve-IVe s. AEC),” Revue d’Ethnoécologie, vol. 4, 2013, pp. 2-18.

Ohshiro, M., “Kharga Oasis and Thebes: The Missing Piece of the Puzzle in the Relocation of Amen Worship in the 27th Dynasty?,” Orient, vol. 43, 2008, pp. 75-92.

Petrie W. F., History of Egypt. Vol. III – From the XIXth to the XXX th Dynasties, London, 1918.

Posener, G., La première domination perse en Égypte: recueil d’inscriptions hiéroglyphiques, Bibliothèque d’étude 11, Cairo, 1936.

Rossi, C. and S. Ikram, North Kharga Oasis Survey (© NKOS/RKMAS 2007), Cairo, 2007. https://www1.aucegypt.edu/academic/northkhargaoasissurvey/home.htm Accessed: 12 September 2025.

Rossi, C. and S. Ikram, The North Kharga Oasis Survey: Explorations in Egypt’s Western Desert, Leiden, 2018.

Schmidt, E. F., Persepolis, vol. 1, Chicago, 1953.

Thibeau, J., Ain Manawir, The Archaeological Gazetteer of Iran, The Pourdavoud Institute Research Project, The University of California, Los Angeles, 2022. https://irangazetteer.ucla.edu/catalogue/ain-manawir/ Accessed: 13 May 2025.

Vittmann, G., “Egyptian Sources,” In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire, edited by B. Jacobs and R. Röllinger, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2021, vol. 1, pp. 155-62.

Wasmuth, M., Ägypto-persische Herrscher- und Herrschaftspräsentation in der Achämenidenzeit. Oriens et occidens: Studien zu antiken Kulturkontakten und ihrem Nachleben 27, Stuttgart, 2017.

Wasmuth, M., “Egypt,” In A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire, edited by B. Jacobs and R. Röllinger, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2021, vol. 1, pp. 259-275.

Winlock, H. E., The Temple of Hibis in El Khārgeh Oasis, Vol. I: The Excavations. New York, 1941.