Jūndishapurجندیشاپور

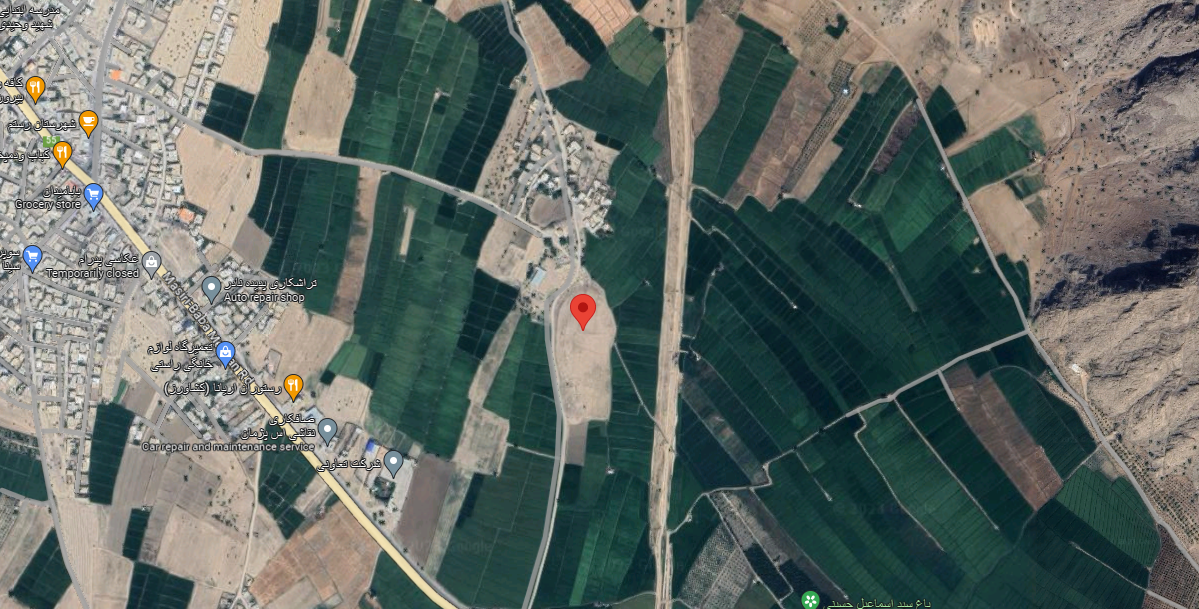

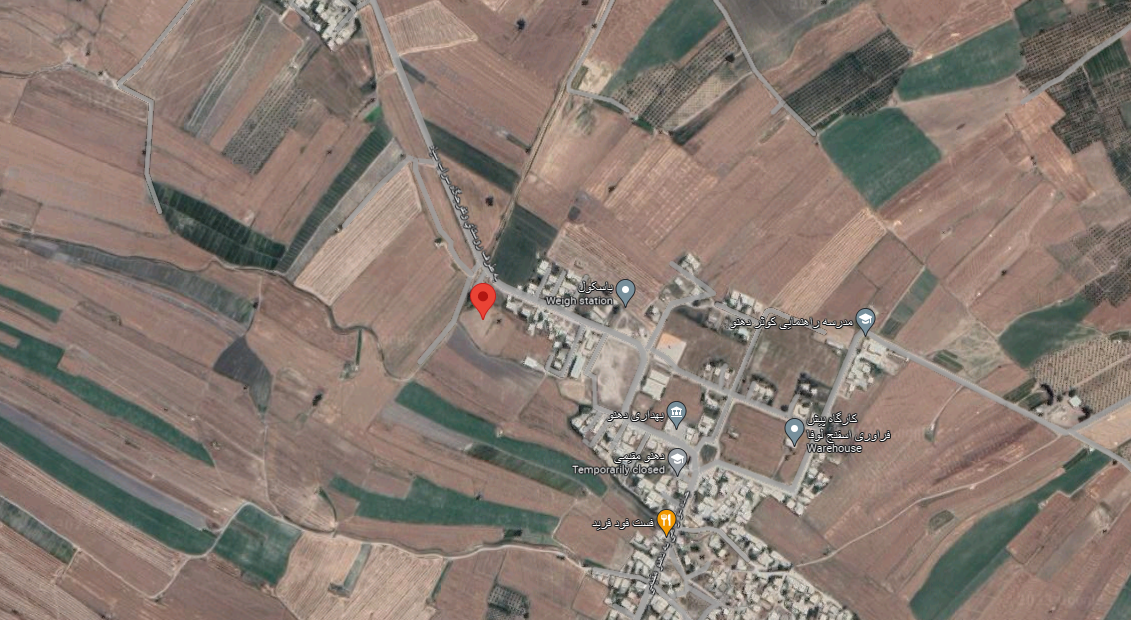

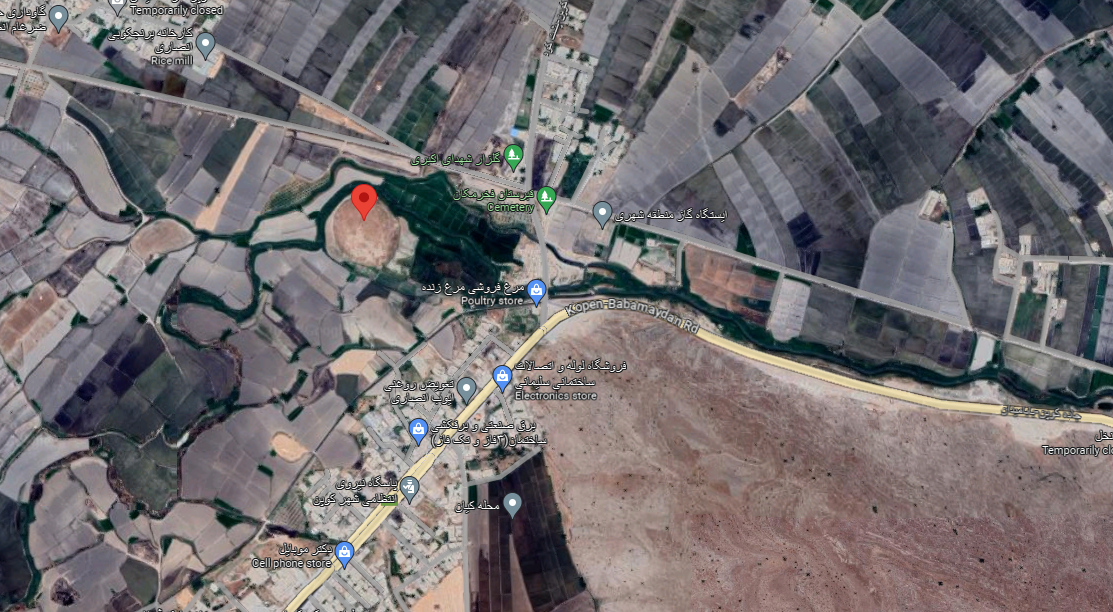

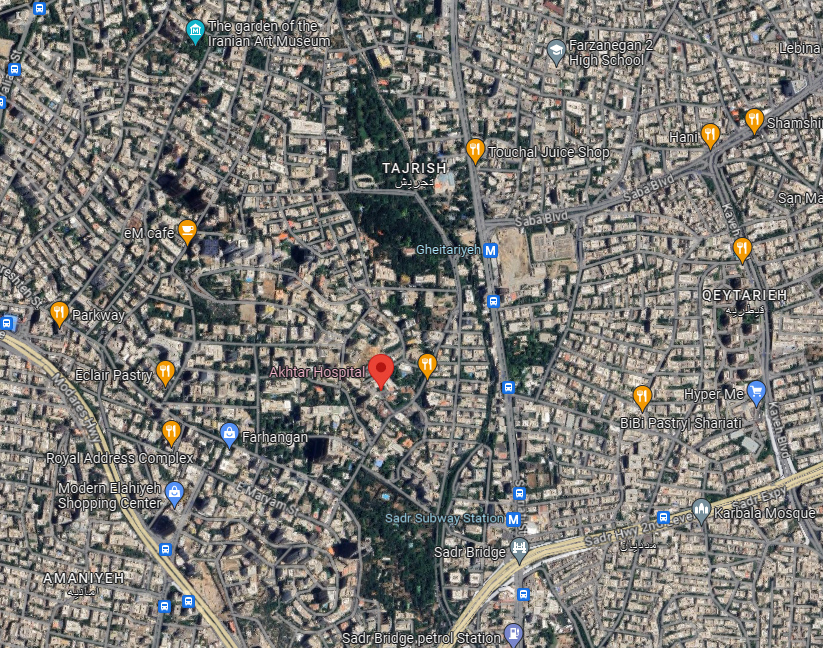

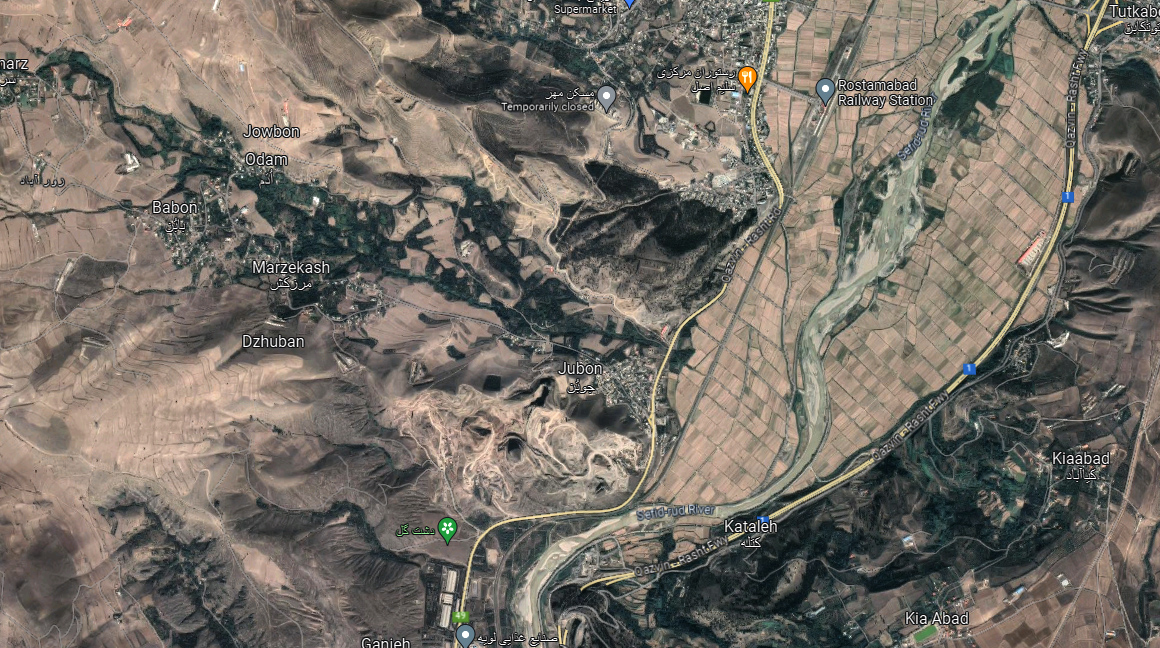

Location: The ruins of Jūndishapur lie in the northern plains of Khuzestan, southwestern Iran, Khuzestan Province.

32°17’01.4″N 48°30’48.0″E

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian, Islamic

History and description

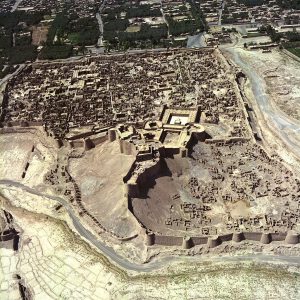

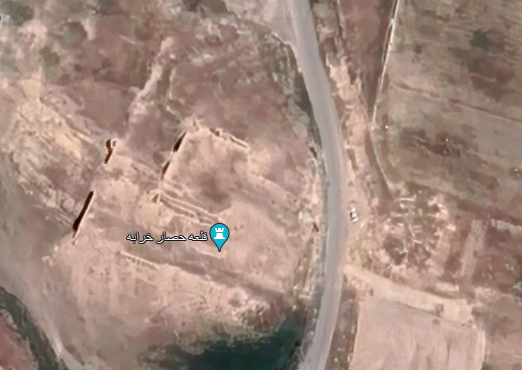

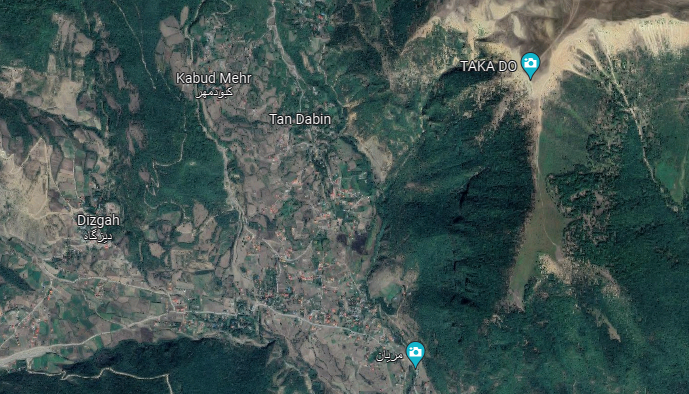

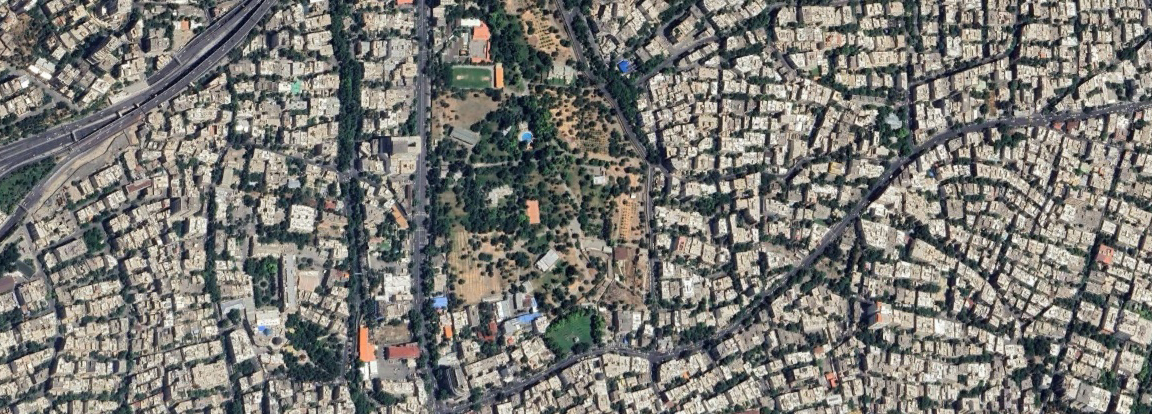

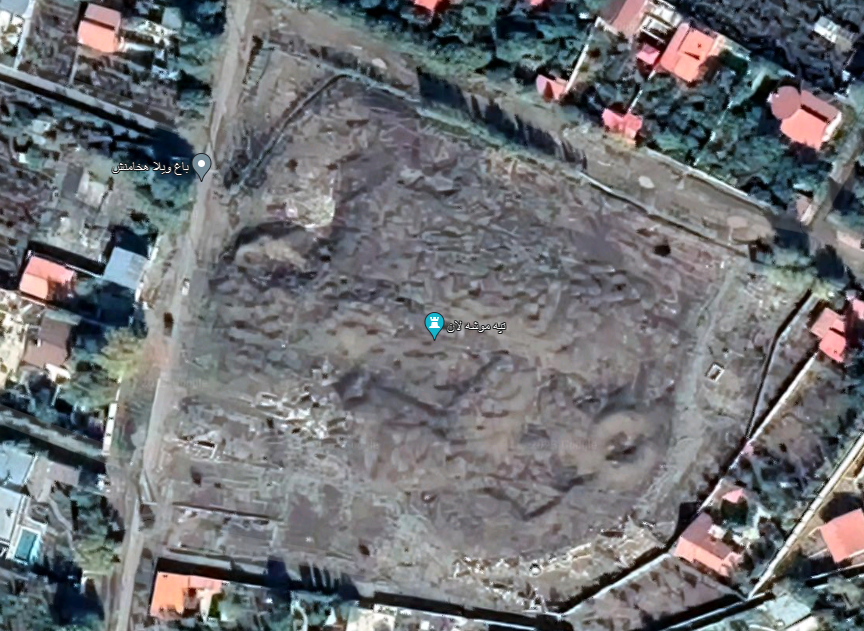

The archaeological site of Jūndishapur is located 5 km southeast of Dezful and 25 km northeast of Susa. The site lies to the south of the village of Eslāmābād hitherto known as Shāhābād. The present layout resembles an irregular rectangle with an approximate area of 150 hectares. The remains delineate an orthogonal street pattern within a rectangular walled area, closely resembling Ḥamza Eṣfahāni’s idealized description of the city’s layout as a chessboard with eight by eight streets. There seems to be no significant trace of any occupation before the 3rd century. Surface findings from the majority of the ruins indicate a peak occupation during the Sassanian period. Notably, the relatively unremarkable eastern and western sections of the city predominantly exhibit sparse Sassanian pottery on the surface. At present, the site’s edges are destroyed because of farming activities.

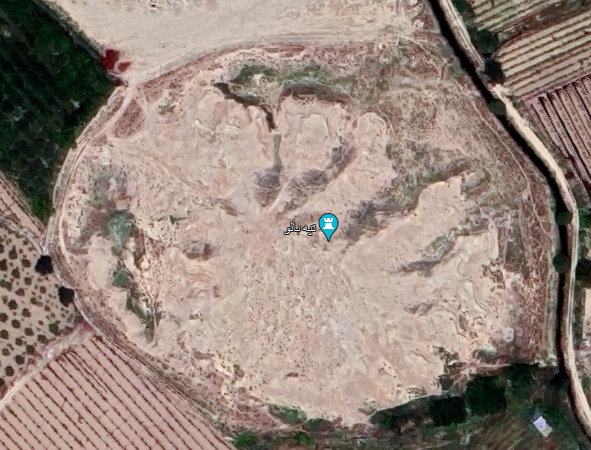

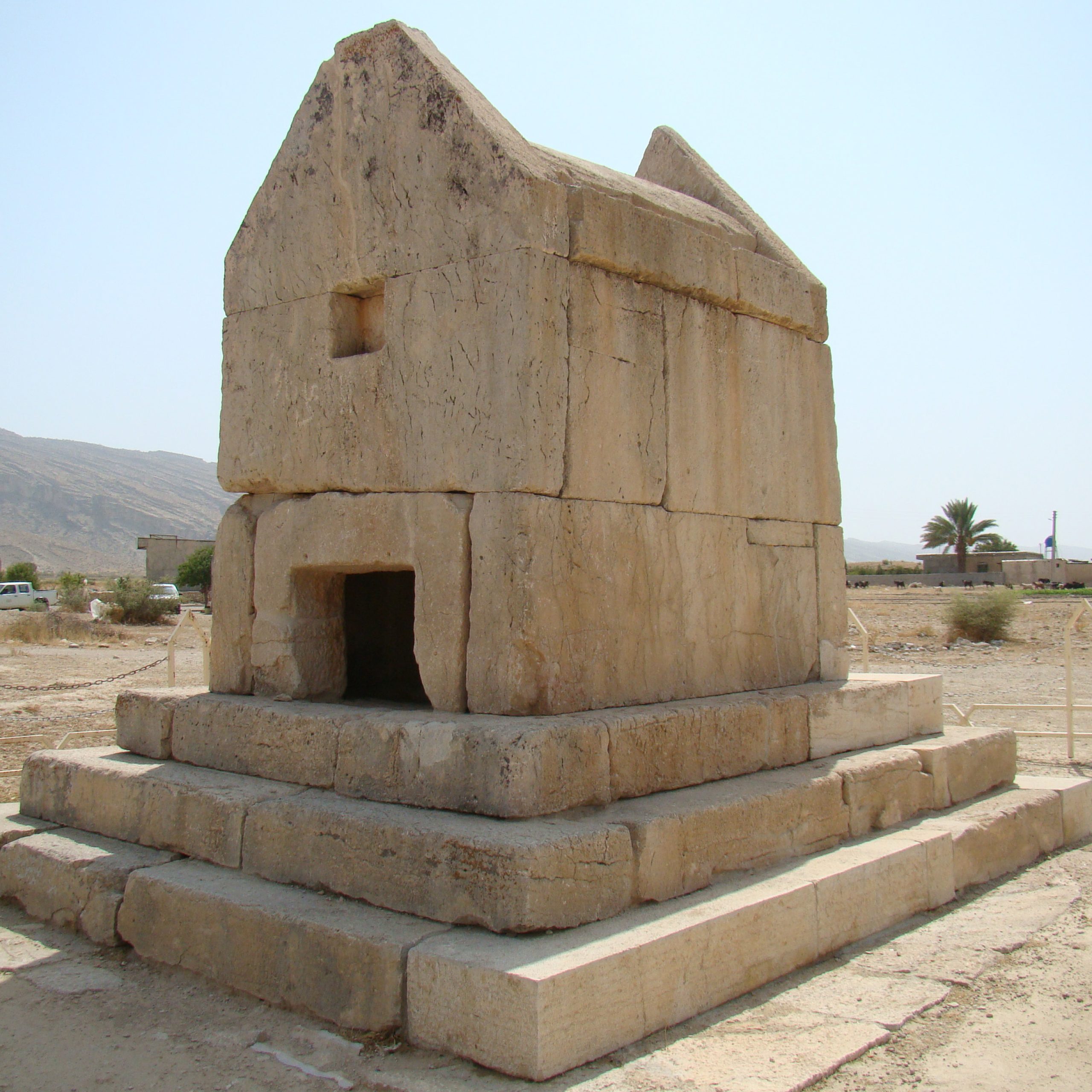

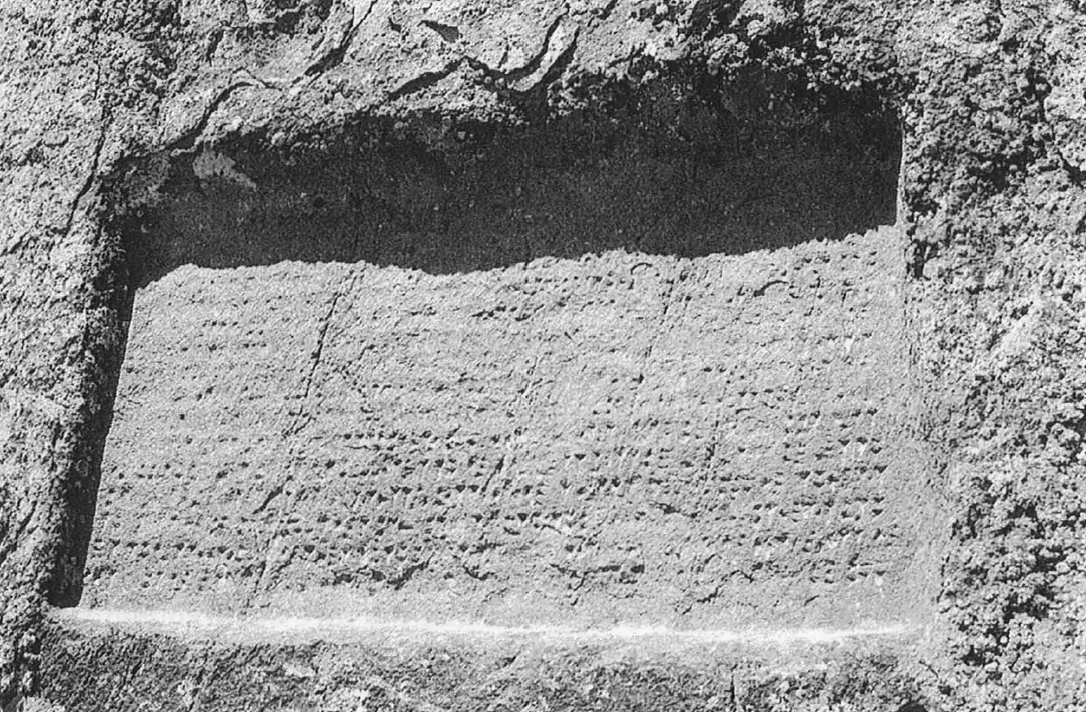

In the absence of any excavated written document, the proposed etymology by Tabari who refers to it as Bih-az-Andiw-i Sābūr, signifying “the city of Shapur which is better than Antioch”, has been largely accepted (The History of Al-Tabari, 831). Hamzeh Isfahani gives a similar account in his History of the Years of the Kings of the Earth and the Prophets. According to the tenth-century polymath and historian, Abu Hanifa Dinawari, after ascending the throne, Shapur launched an invasion into Roman territories. Upon his return to Iraq and the land of Ahwaz, he sought a suitable location to settle the war prisoners. Therefore, he founded Jūndishapur (the Arabicized form of Gūndishapur), referred to as Nilāt in the Khuzi language, while the local inhabitants call it Nilāb (Akhbar al-tiwal, 46). The city is said to be the place where Mani was executed in A.D. 273 or 277. All medieval sources attest that Jūndishapur was a prosperous city throughout the Sasanian period down to the time of the Abbasid caliphs. Maqdisi, writing in the 10th century, informs us that the city suffered from the incursions of Kurds but was still famous for its tasteful water, embroideries, and particularly for the cultivation of sugar cane (Schwarz, Iran im Mitelalter, pp. 346-349; Le Strange, The Land of the Eastern Caliphs, p. 238). Yaʿqub b. Layth, “aspiring to imitate the Sasanians,” chose Jūndishapur as his capital and died there in 265 H./A.D. 879. His tomb became the central and the only standing monument amongst the city’s ruins.

Jūndishapur’s significance was heightened by its association with a secular domain of knowledge, specifically medicine, and by its role as a leading exponent of Greek medical traditions. The earliest record of Jūndishapur in the context of medical education dates back to a medical-philosophical debate convened around A.D. 610, on the orders of Khosrow II. As reported by Ibn al-Qefti, the specific mention of the hospital itself is found in the events of the year 148 H./A.D. 765 when the caliph al-Mansur reportedly summoned a certain Bokhtishū, the then head of Jūndishapur’s hospital, to Baghdad (Tarikh al-Hokama, pp. 158-60). The city declined after the 10th century, particularly after the Mongol invasion that ended the Abbasid caliphate in A.D. 1258.

Archaeological Exploration

In 1882, Marcel and Jane Dieulafoy visited the site of Jūndishapur, known under the name of the nearby Imamzadeh, Shahabad.

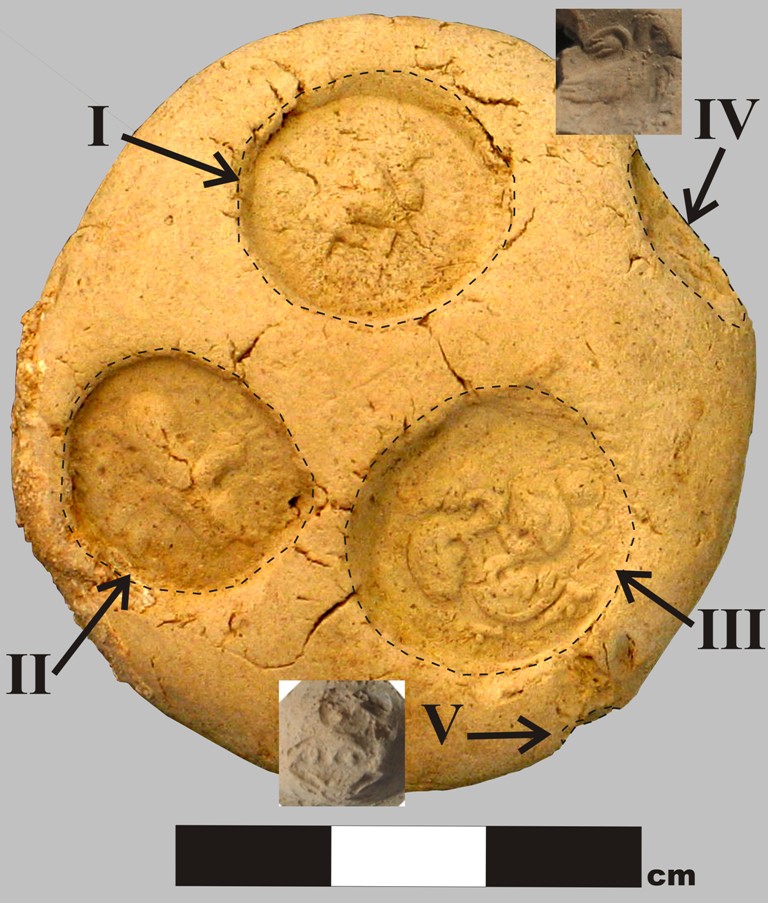

In 1963, Robert MacCormick Adams, then at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, conducted excavations at Jūndishapur with the assistance of Donald P. Hansen. Adams dug four soundings at the site. According to Adams, the objective of these soundings was “to test the depth of stratified refuse and to probe the extent and character of architectural remains underlying some of the widely scattered mounds within the city area.” The first sounding was at Tabl Khaneh, one of the most conspicuous mounds at Jundishapur. The site for a second sounding was selected at plain level, amid a low group of mounds, 250m west-northwest of Tabl Khaneh. The third sounding was strategically positioned on the northwest portion of the site, atop the sizable and prominent mound known as Kashk-e-Bozi, where several graves were uncovered “without offerings and hence of uncertain date.” For Adams' final sounding, a trench measuring 10 by 3 meters was dug along a northeast-southwest ridge on the city wall. Regrettably, Adams did not publish a comprehensive report of his fieldwork at the site. As Donald Withcomb writes, Adams’ limited excavations yielded little success, leaving “unexplored monuments known from historical sources – the medical academy, astronomical observatory, Nestorian cathedral and monastery, the congregational mosque and madrasas.”

In the winter of 2017, Yusef Moradi excavated at Jūndishapur on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research. During the excavations of the first season, a part of a residential building was identified. This building has a relatively large yard with direct access to a warehouse, kitchen, and living rooms. A staircase leads to underground rooms in the northwest corner of the yard. The excavated house in the Chaghaya area is part of a residential sector built within the city’s moat. The city’s urban area in the late Sasanian or early Islamic period expanded beyond the northern wall.

Finds

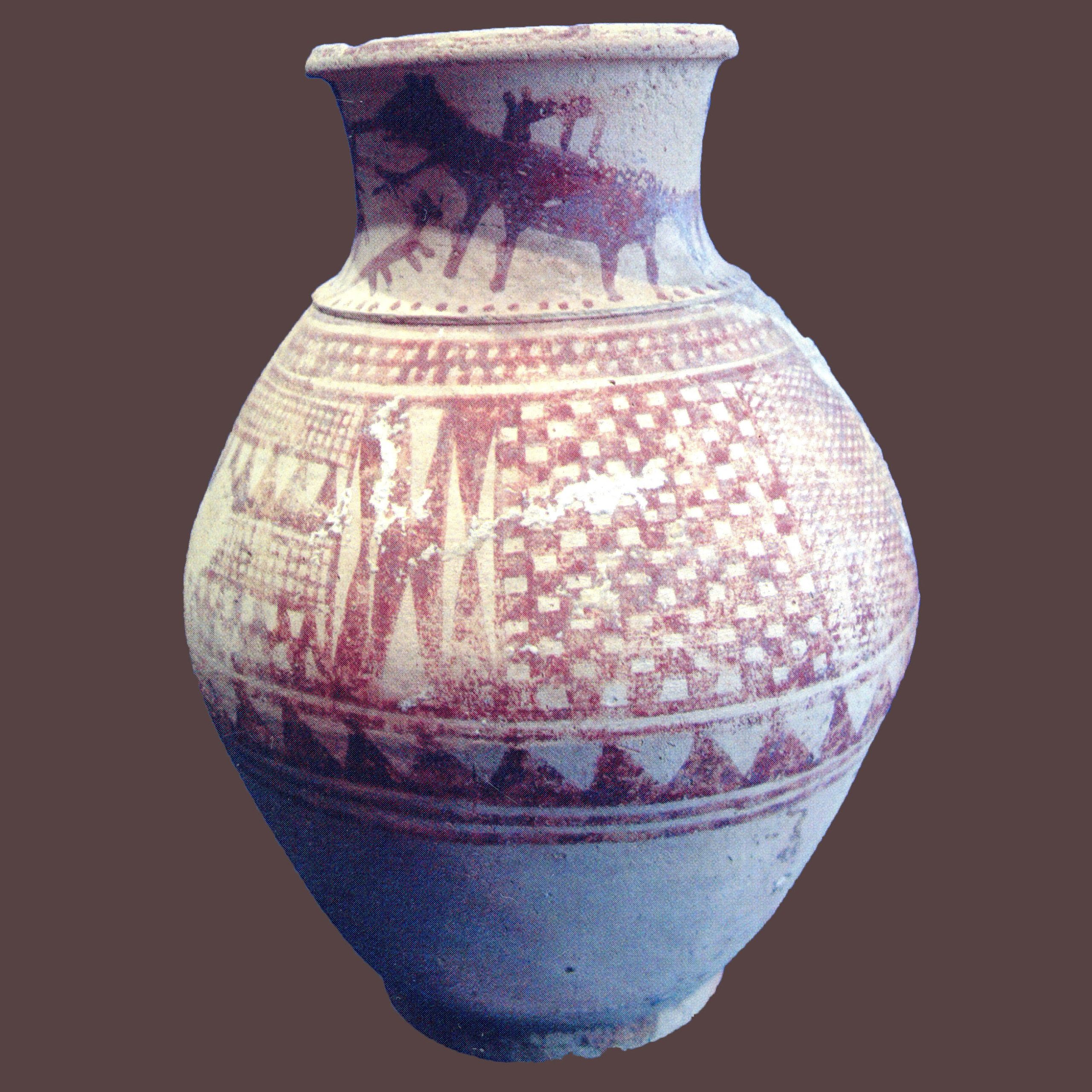

The excavated finds mostly consist of potsherds.

Bibliography

Adams, R. McC and D. P. Hansen, “Archaeological Reconnaissance and Soundings in Jundi Shāhpur,” Ars Orientalis, vol. 7, 1968, pp. 53-70, with appendix by Nabia Abbott, “Jundi Shāhpur: A Preliminary Historical Sketch,” pp. 71-73.

Barthold, V. V., An Historical Geography of Iran, Princeton, New Jersey, 1984, p. 188.

Dieulafoy, J., La Perse, la Chaldée, la Susiane, Paris, 1887, p. 672.

Le Strange, G., Lands of the Eastern Caliphate, Cambridge, 1905, p. 238.

Moradi, Y., “The First Season of Excavations at the S-Called Site of Jundishapur,” The 16th Annual Symposium on Iranian Archaeology (A collection of short articles, 2016-2017), 5-6 March, 2019, Tehran, 1397/2019, pp. 342-346.

Potts, D. T., “Gundešapur and Gondeisos,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 24 1989, pp. 323-35.

Rāst, N., “Qabr-e Yaʿqub b. Layth,” “Yādgār 5/4-5, 1327, pp. 123-29.

Schwarz, P., Iran im Mitelalter, vol. IV, Leipzig, 1921, pp. 347-349.

Shapur Shahbazi, A. and L. Richter-Bernburg, “Gondēšāpur,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, ©Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

Withcomb, D., “Iranian Cities of the Sasanian and Early Islamic Periods”, The Oriental Institute Annual Report 2003-2004, Chicago, 2004, pp. 91-99.

Withcomb, D., “Toward an Archaeology of Sasanian Cities,” Proceedings of the International Congress of Young Archaeologists, Tehran, 2015, edited by H. Azizi Kharanaghi, M. Khanipour, and R. Naseri, vol. 3, Tehran, 2018, pp. 258-261 (for Jūndishapur).