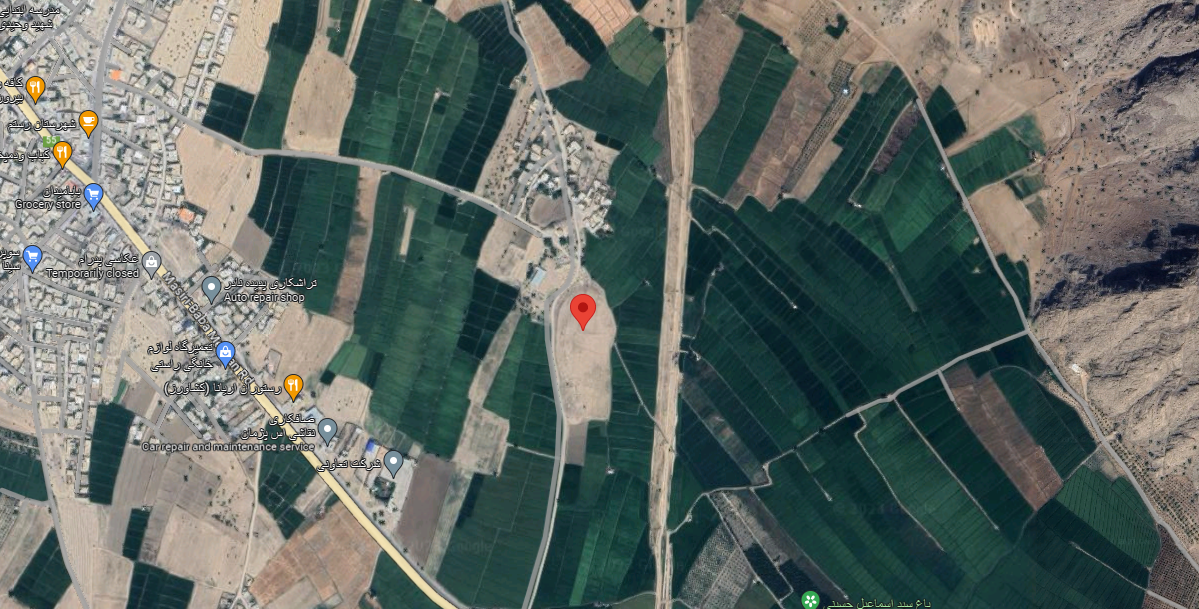

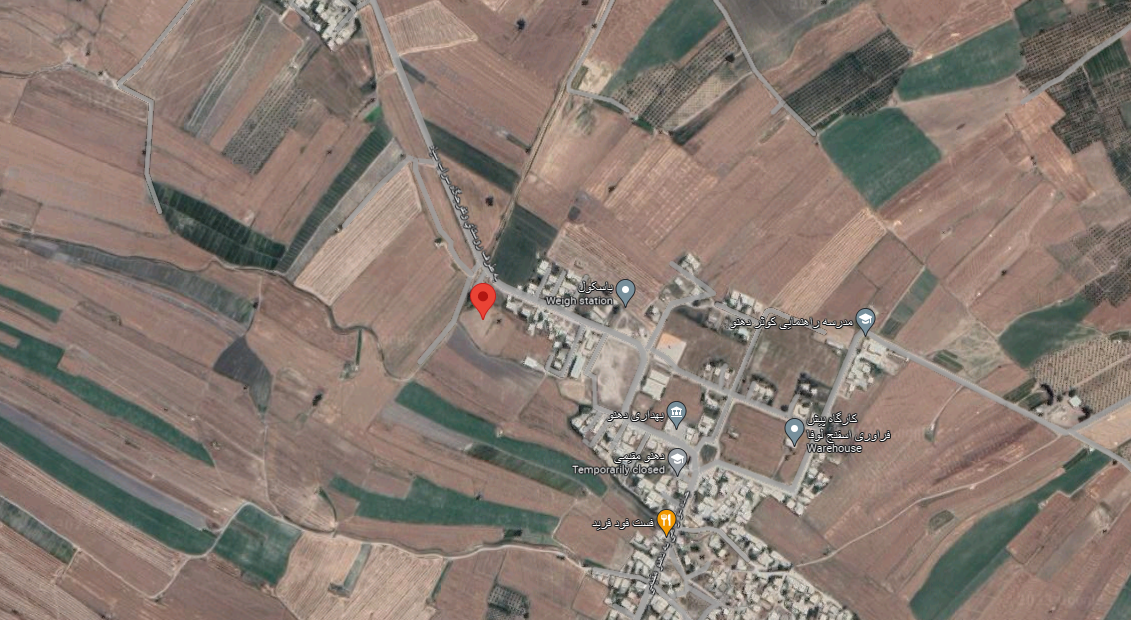

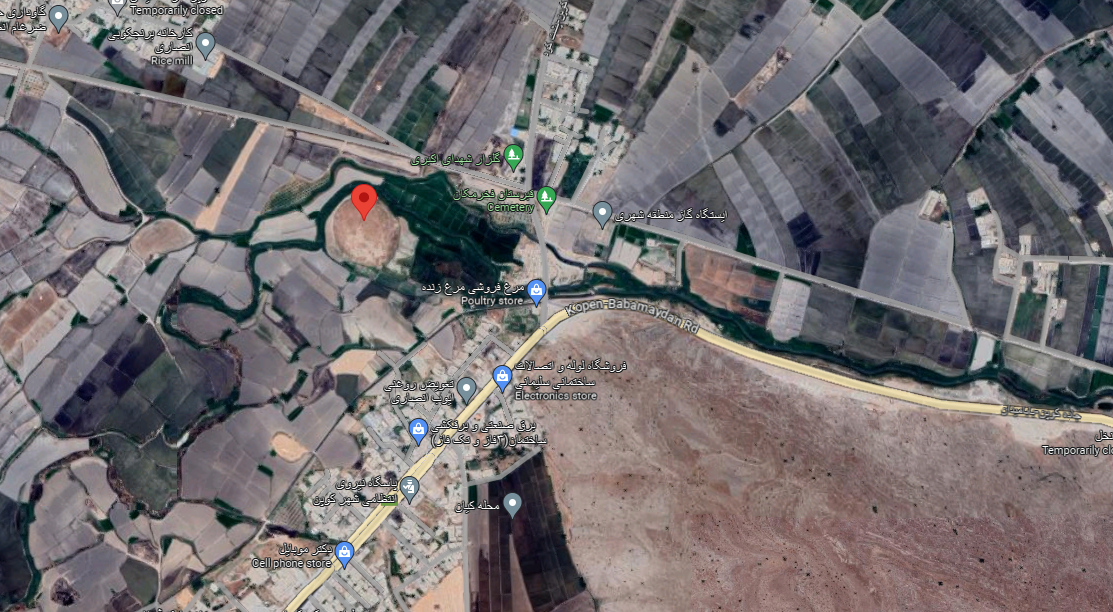

Haft Tepeهفت تپه

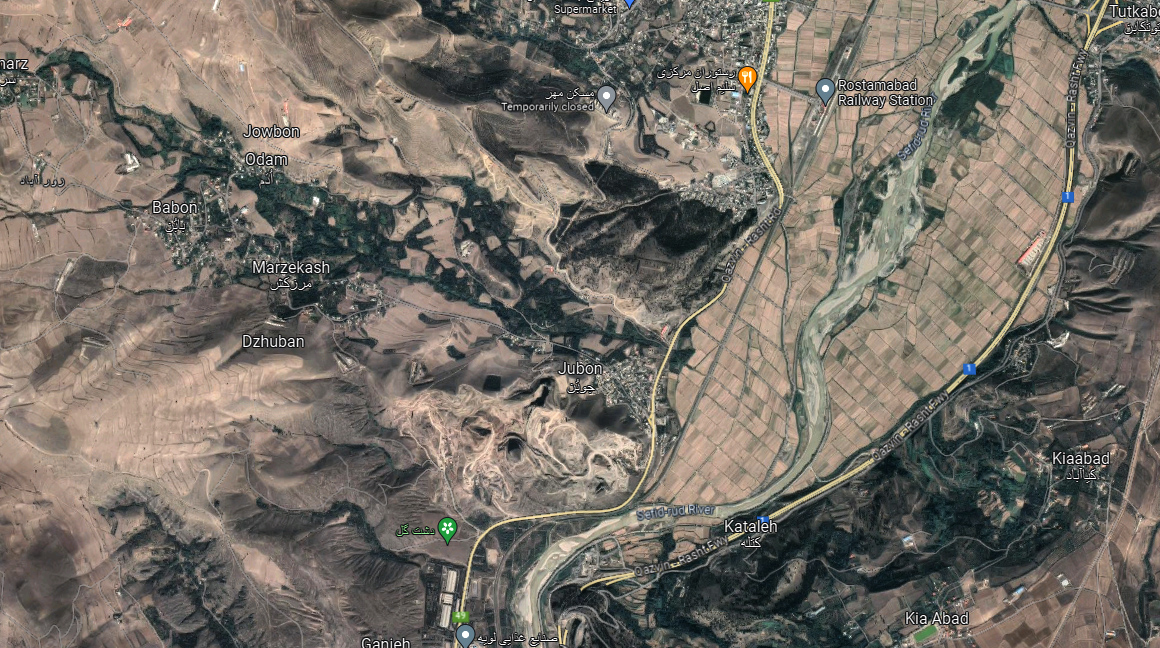

Location: Haft Tepe is a large Elamite site, in southwestern Iran, Khuzestan Province

32° 4’51.30″N; 48°19’41.16″E

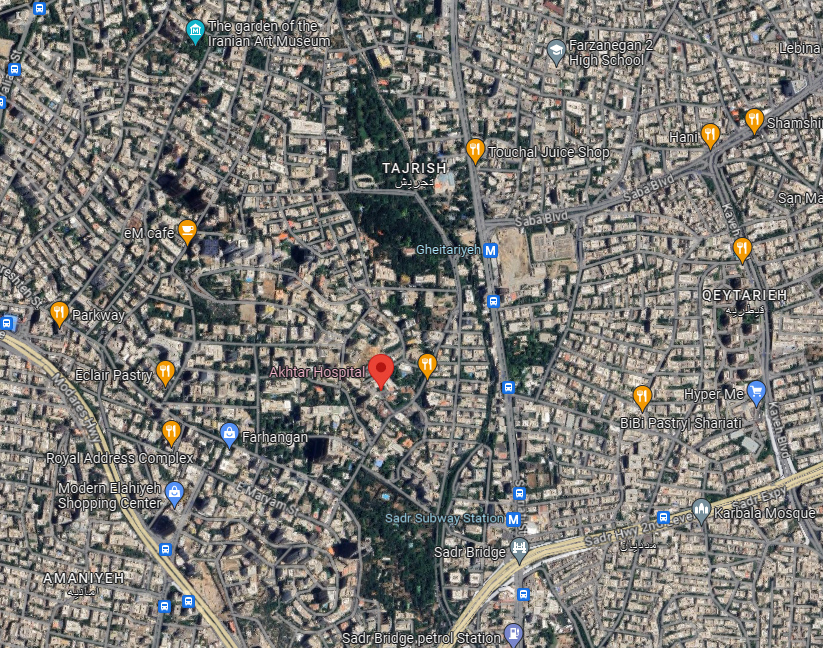

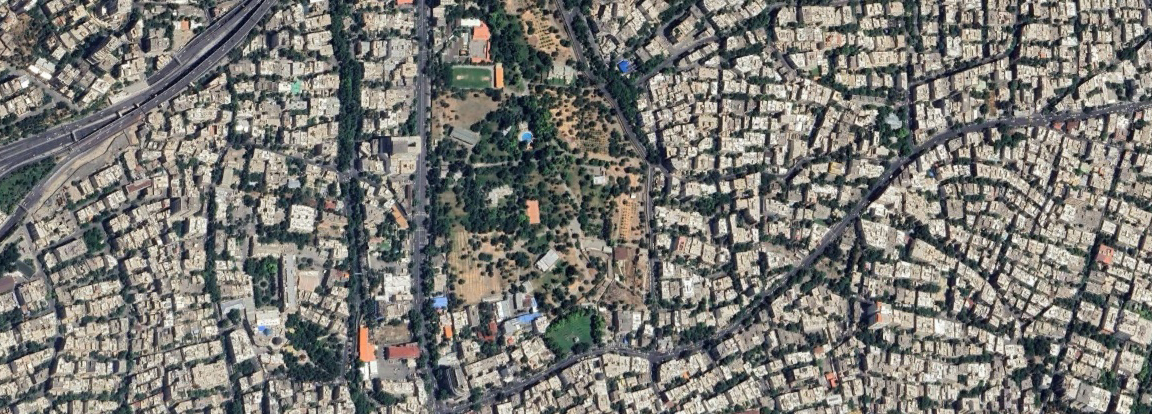

Map

Historical Period

Bronze Age / Elamite

History and description

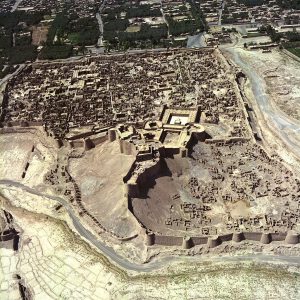

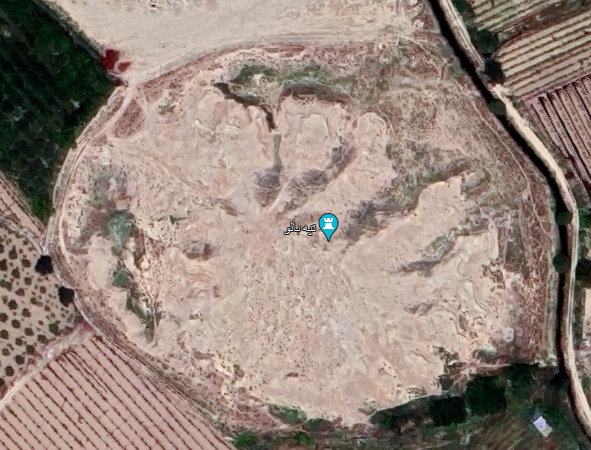

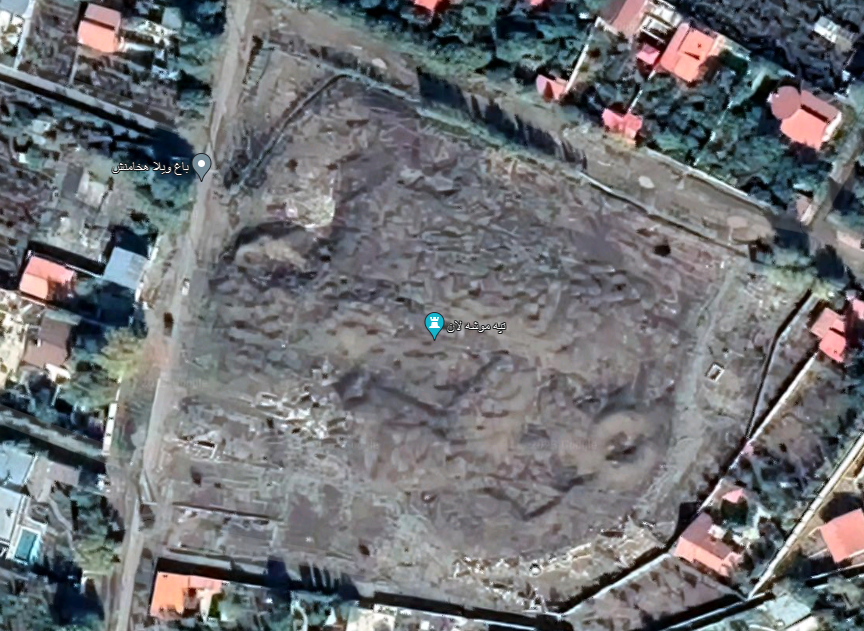

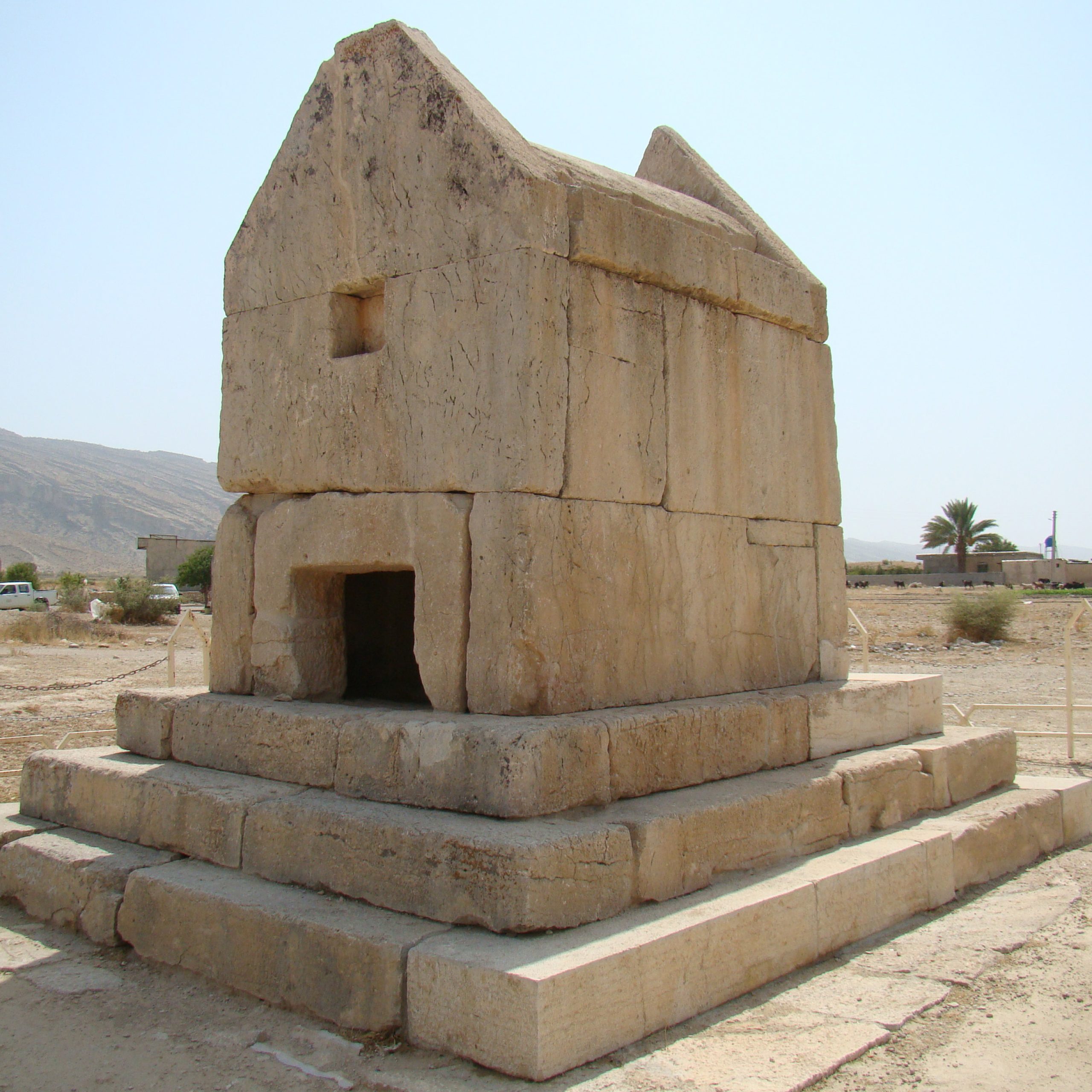

The site of Haft Tepe is located in the fertile plain of Khuzestan, between two major rivers of the region, the Dez and the Karkheh. The Shāur River flows some 4 km west of the site; a stream called Nahr-e Atigh/Atij flows along the western edge of the mounds. The present name Haft Tepe or the Seven Mounds refers to a cluster of mounds. The word haft (seven) in Persian is often used loosely to indicate a large number or a group of many.

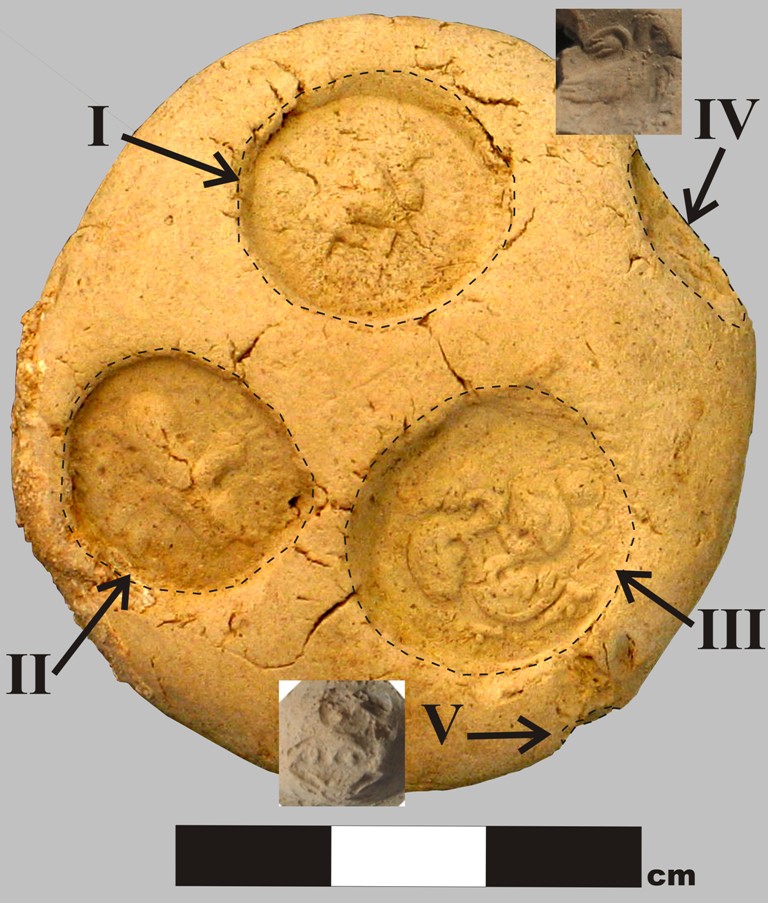

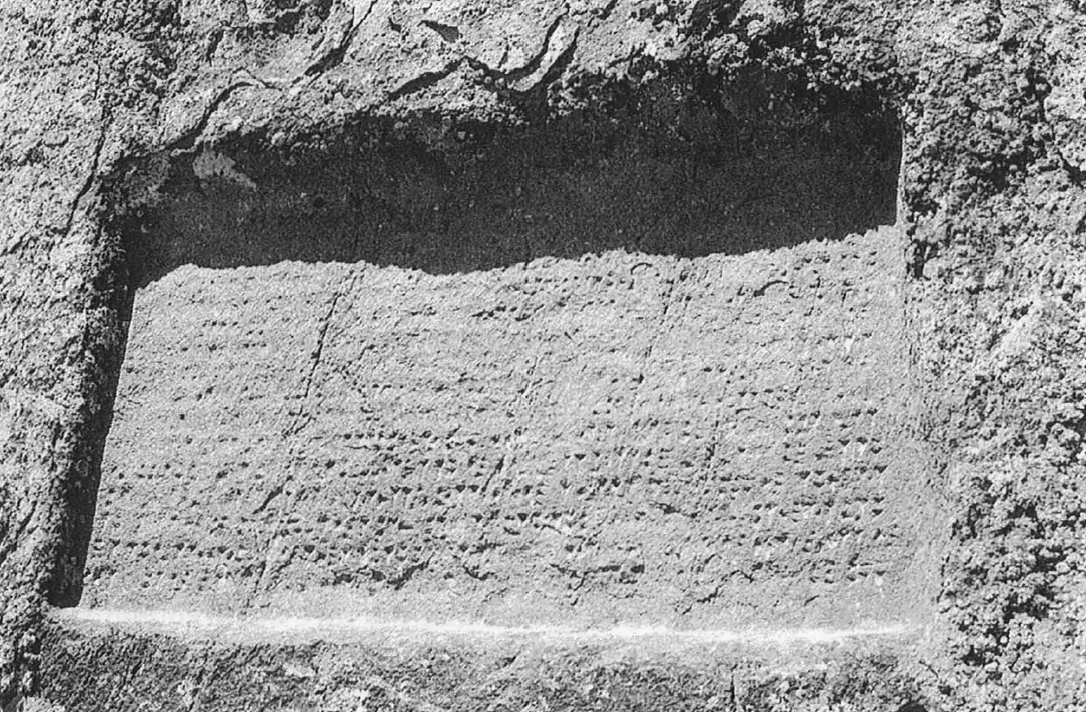

Tablets found at the site refer to the geographical name Karnak. Besides, the seal impression on tablets found at Haft Tepe mentions the name of a certain Atkhibu as the owner of the seal and the governor of Kapnak in the service of the Elamite king Tepti Ahar. Later, Assyrian texts reporting the campaign of Ashurbanipal against Elam in 646 B.C. mention the town of Kapinak in the vicinity of Susa (Herrero, “Tablettes administratives de Haft Tépé,” p. 102; Negahban, Excavations at Haft Tepe, p. 109; see also Potts, The Archaeology of Elam, pp. 201-204).

The site of Haft Tepe was first occupied during the Sukkalmah period (c. 1900-1600 B.C.), the remains of which have been discovered in recent excavations (Mofidi-Nasrabadi, “Ergebnisse der C14-Datierung der Proben aus Haft Tappeh,” pp. 28-29; “Vorbericht der archäologischen Ausgrabungen,” figs 9-10). The Sukkalmah period settlement lay in the northern sector of the site, but the exact nature of it is still unclear due to the excavation of limited small areas underneath the Middle Elamite period levels (Mofidi-Nasrabadi, “Some Chronological Aspects,” pp. 168-169).

Archaeological Exploration

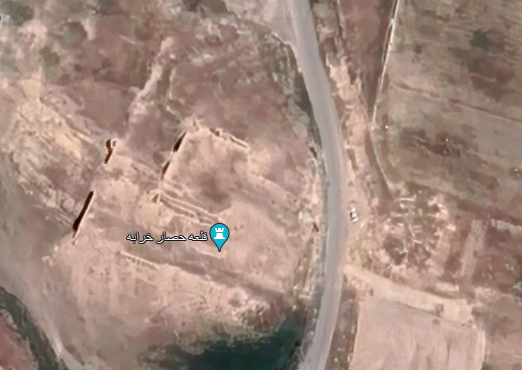

The site of Haft Tepe has been known since the 1900s. Jacques de Morgan, the famous French excavator of Susa, briefly described the ruins under the name of Haft Shoghāl (Haft Choghā) in 1908. Due to the construction of a road for the modern sugarcane plantation and factory, part of a brick vault tomb was unearthed which triggered a long archaeological investigation on the site. Before the excavation, in Haft Tepe, most of the archaeological investigation was conducted by the French team at the Khuzestan plain and Haft Tepe is the first main site in Khuzestan that was excavated by Iranians themselves. Negahban conducted fourteen archaeological seasons at the site that continued until 1979. He started his work from the discovered tomb and extended it to the south by the one hundred and fifty 10 to 10-meter trenches resulting in unearthing 1.5 ha of the city. His excavations revealed a series of monumental remains such as two large, vaulted tombs, an area named Terrace complex I containing a mud-brick terrace with two large courtyards one at the east (E. C.) with a workshop and a large pottery kiln, and one other courtyard at the Northwest (N. W. C.) with several connected rooms, and another mud-brick terrace called Terrace complex II. In 2001, Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi began a new archaeological project at the site on behalf of the University of Mainz, Germany. The new project started with geomagnetic surveys of the site followed by eight seasons of excavations. The excavation was done in five different areas within fifty 10 to 10-meter trenches. The geophysical and archaeological investigations clarified that the above-mentioned Terrace complexes I and II were part of five monumental architectural complexes (A to E) with different functions. To this, one should add the administrative building discovered in the southern part of the city in area I, including hundreds of cuneiform clay tablets.

Finds

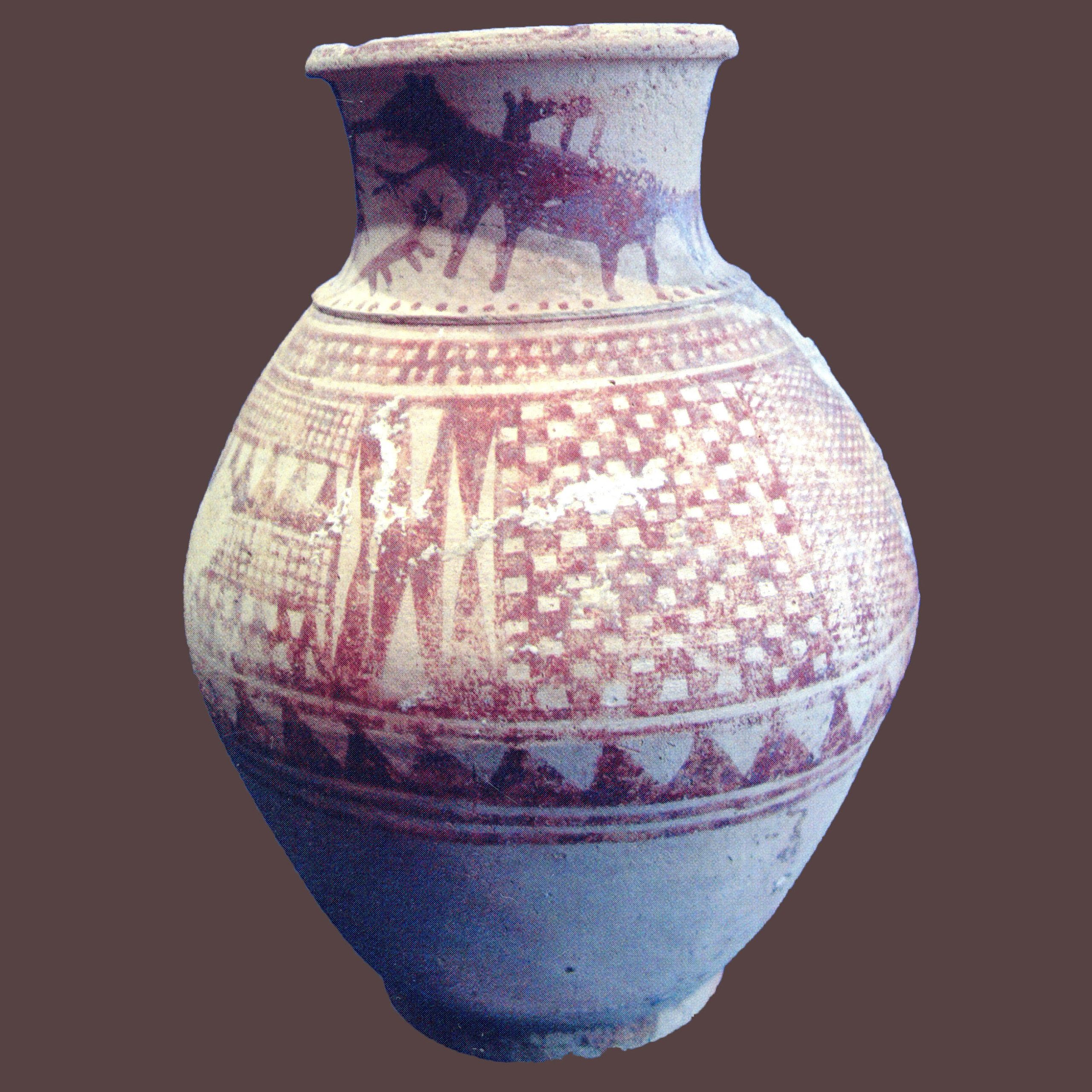

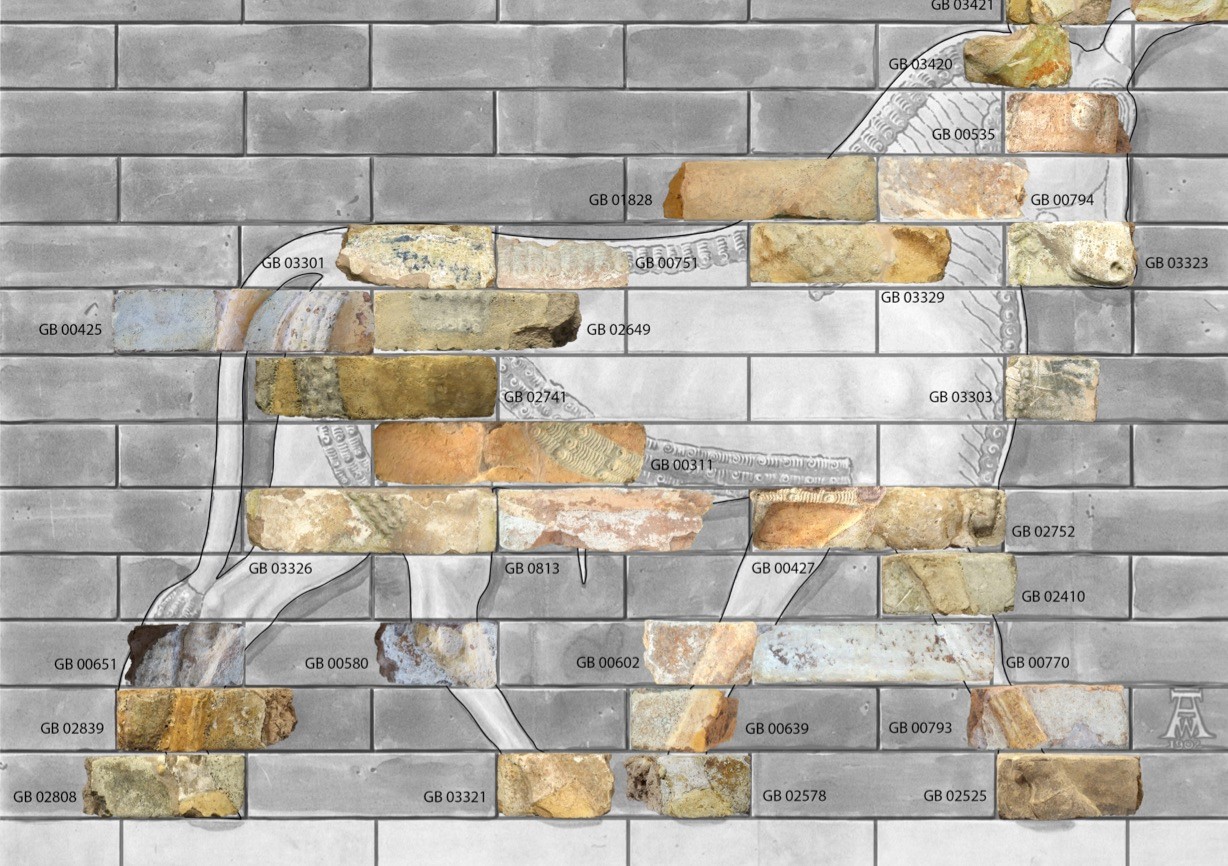

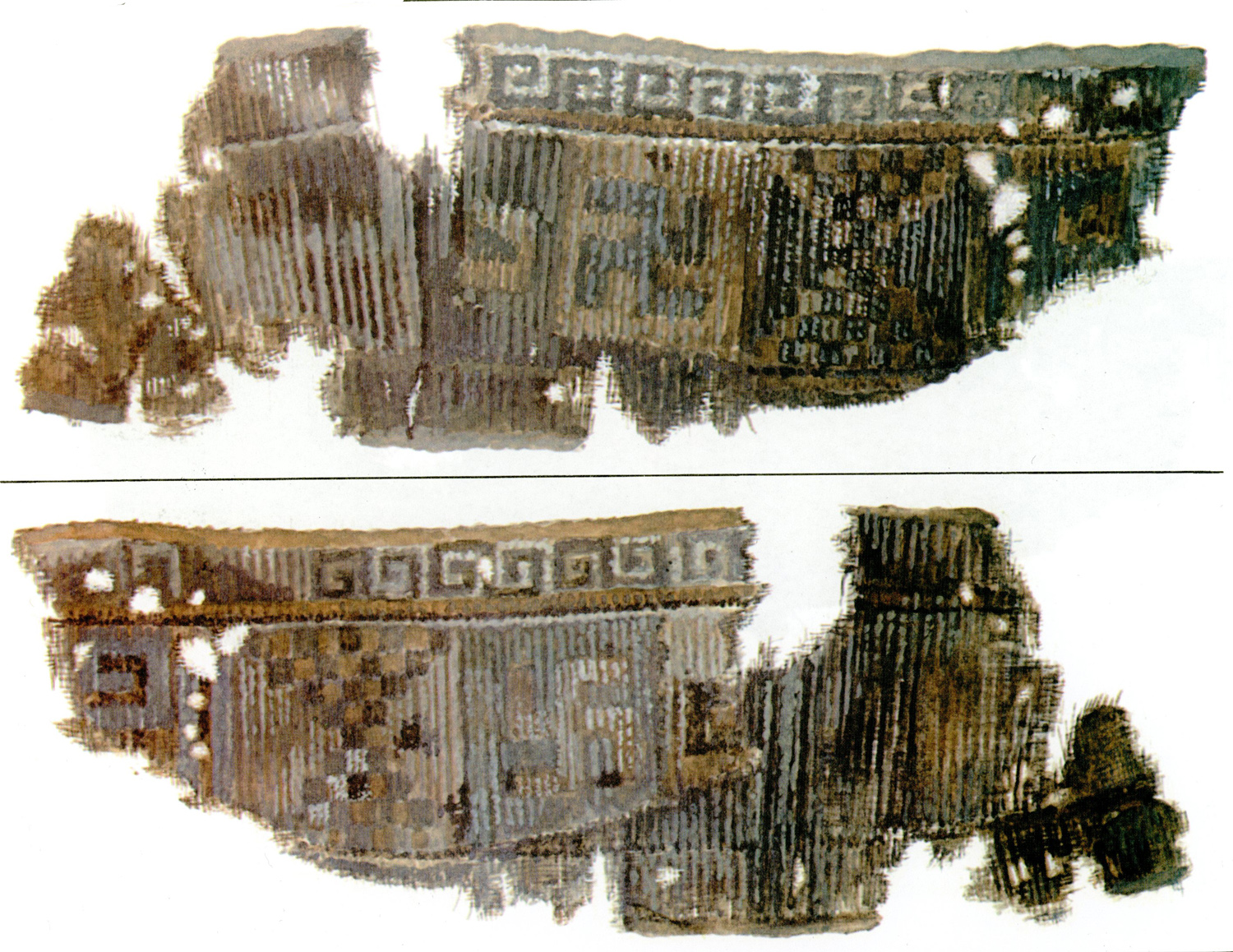

Excavated finds are widely diverse and abundant. Aside from architectural vestiges, the finds consist of pottery, statues and figurines, stone metal and bone objects, seals and seal impressions, monumental inscriptions and tablets, and decorative objects. The pottery assemblage of the Haft Tepe is vastly diverse and helps to elucidate the Elamite repertoire of ceramics and their characteristics in the Khuzestan plain during the second millennium B.C. . The majority of ceramics are typical of the Middle Elamite period with tall jars with a pointed or flat base.

The most dramatic excavated finds are human figures in baked clay, animal figurines, bed models, wall paintings, composite human heads, bitumen objects, and ceramic rattles. Among the objects in metal, one has to mention the decorated bronze plaque with a scene depicting a deity, possibly the god Nergal, with a nude female kneeling in front of him and praying behind him.

Bibliography

Author: Babak Rafiee

Originally published: November 16, 2021

Last updated: January 10, 2025