Gonbad-e Qābūs / Gonbad Kāvūsگنبد کاووس / گنبد قابوس

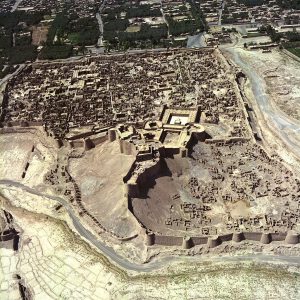

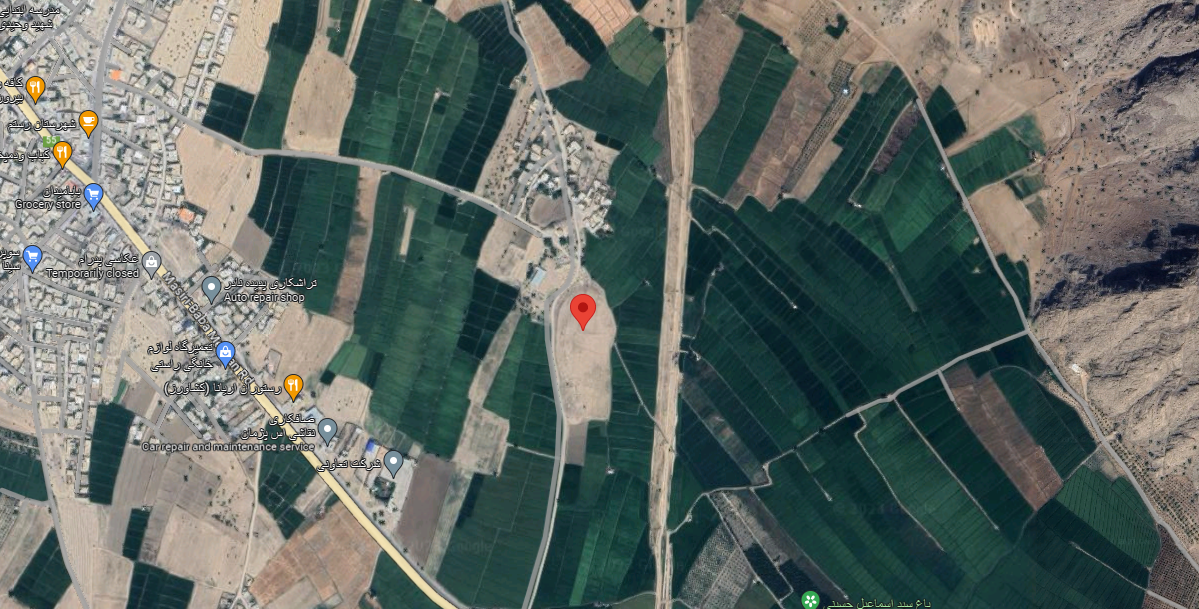

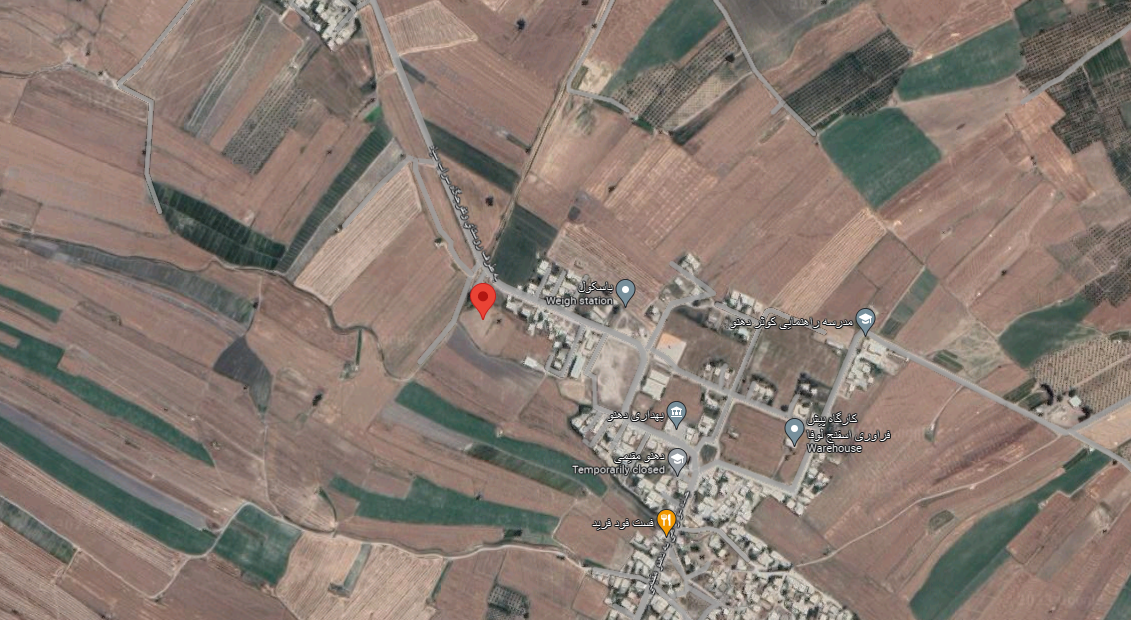

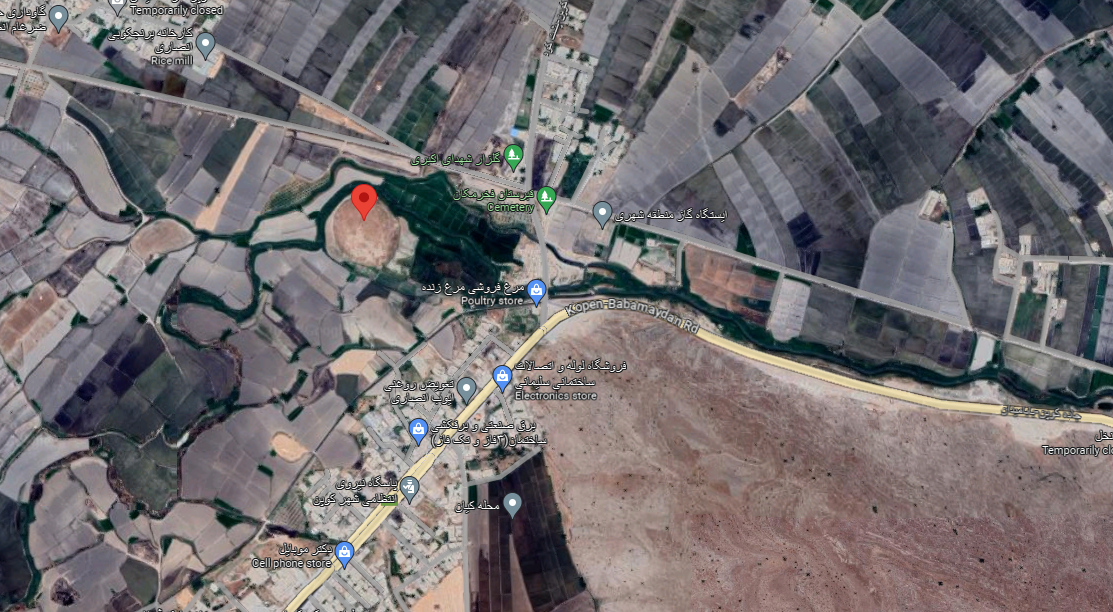

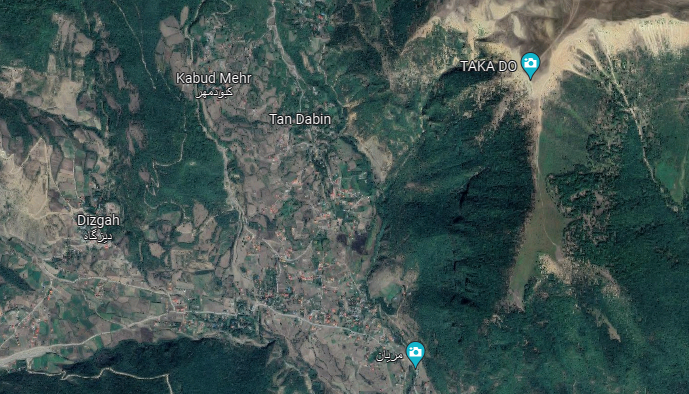

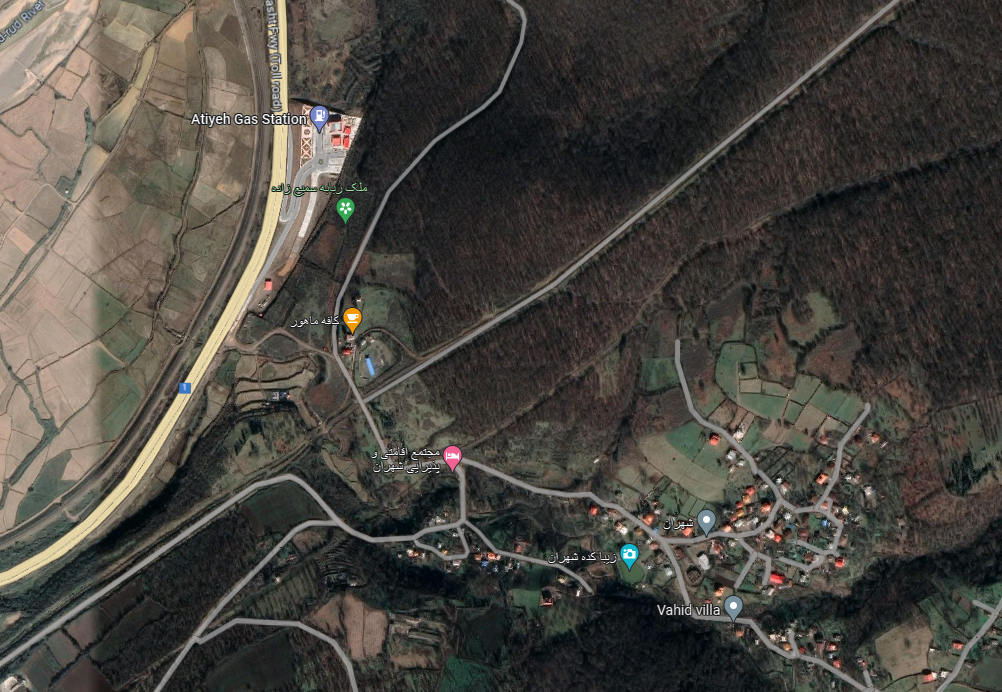

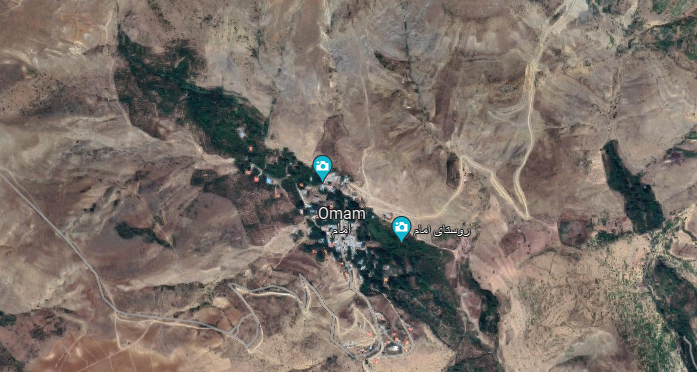

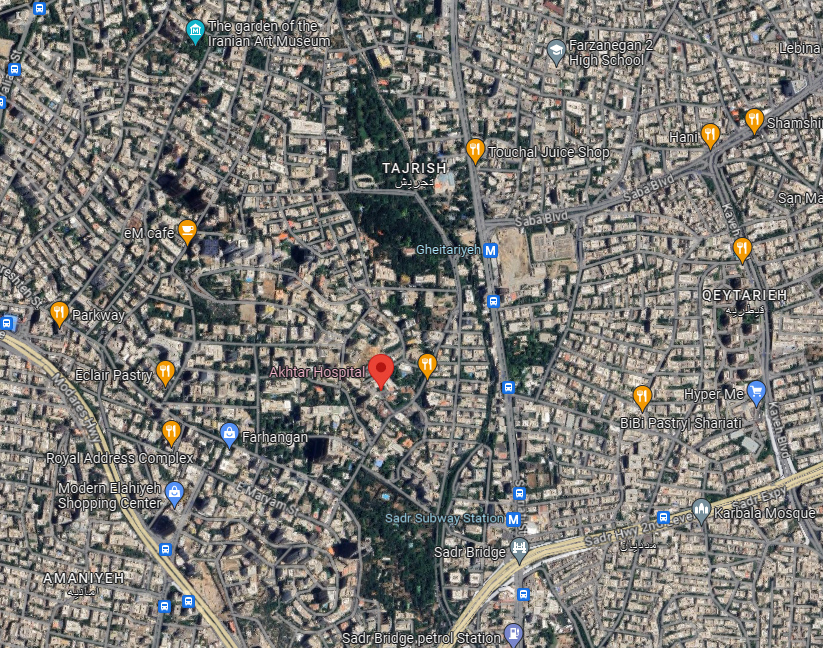

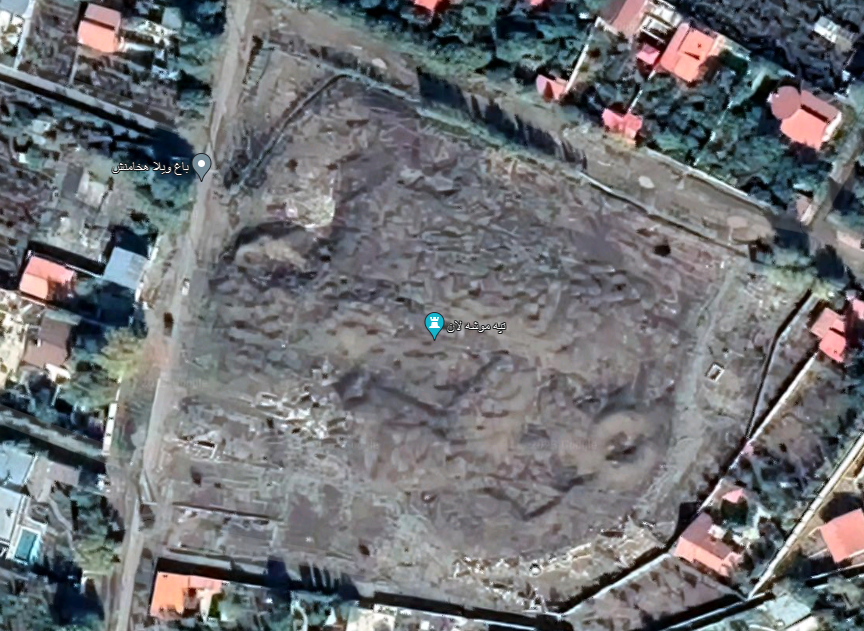

Location: The Gonbad-e Qābūs tomb tower is in the town of Gonbad-e Qābūs in northeastern Iran, Golestan Province.

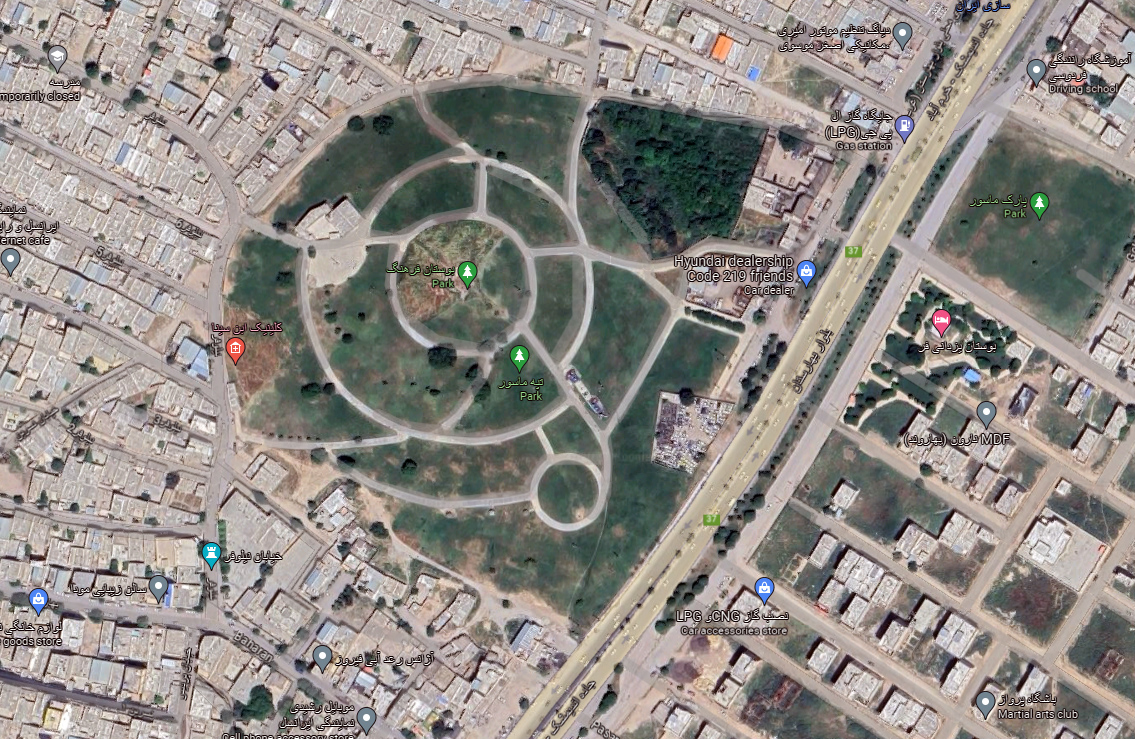

37°15’28.7″N 55°10’08.3″E

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

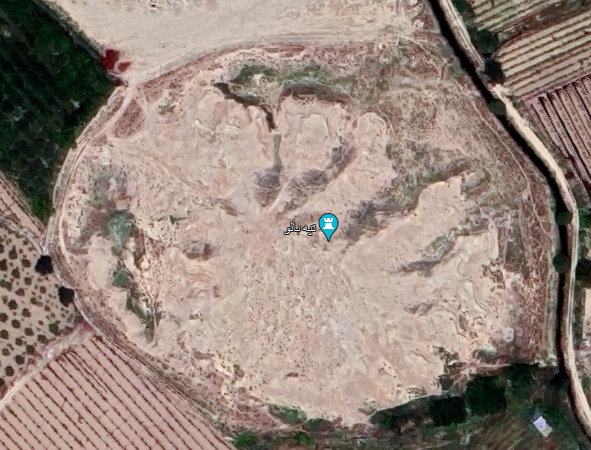

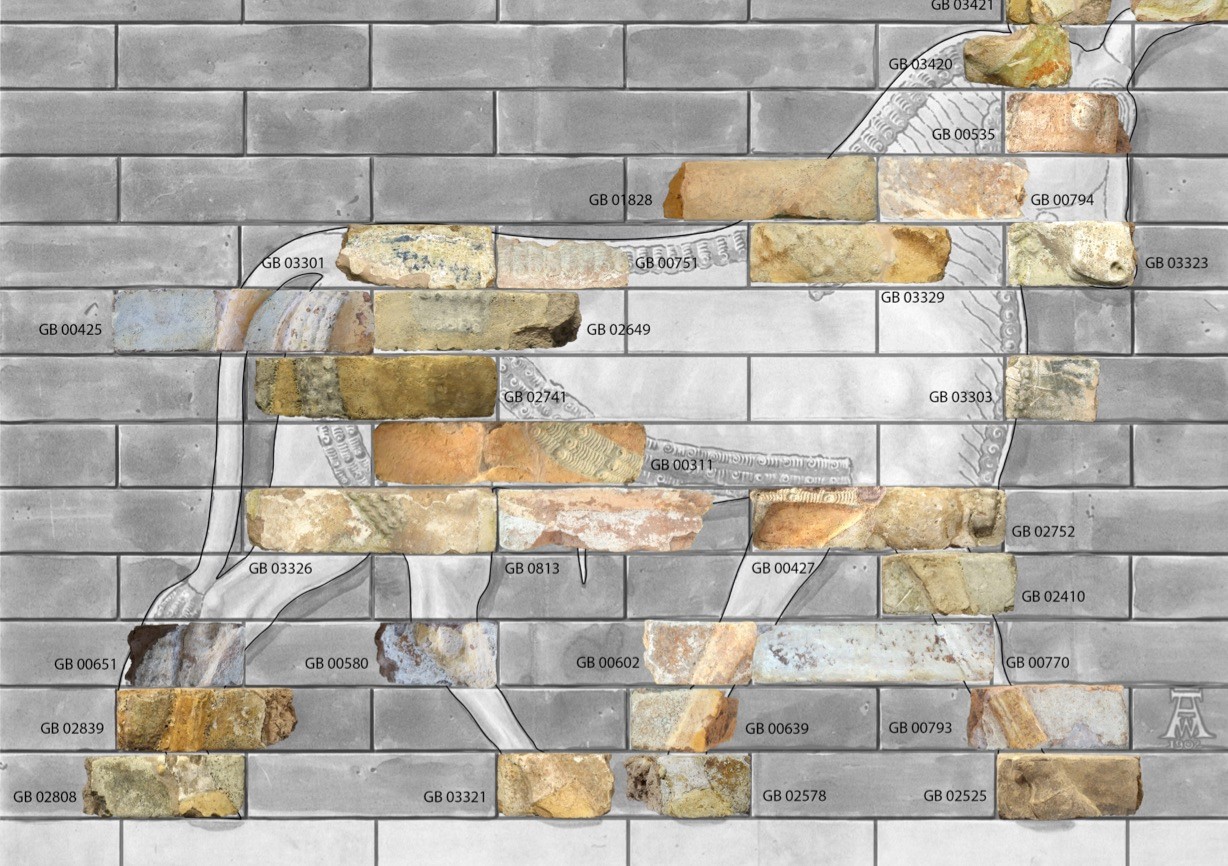

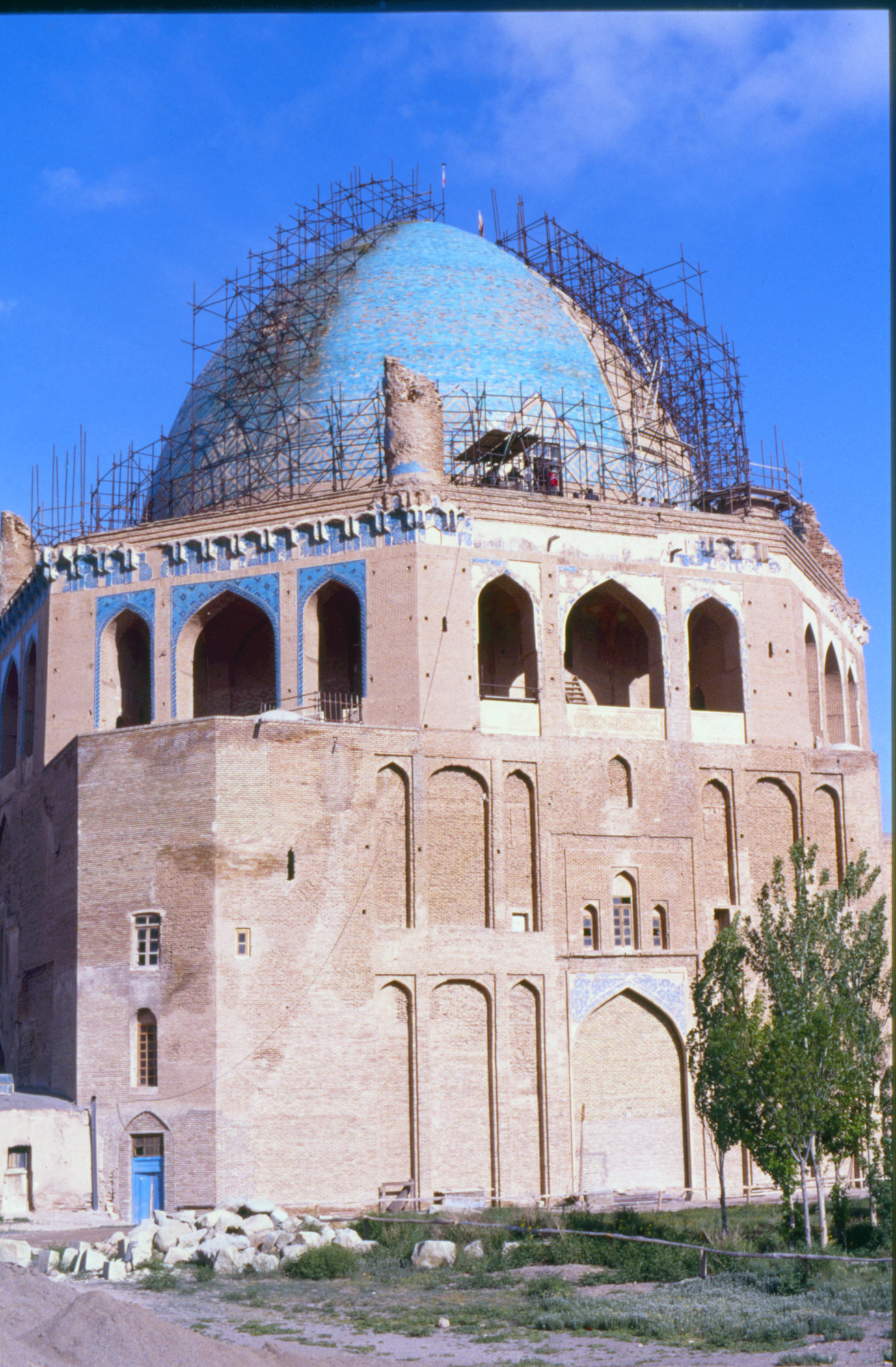

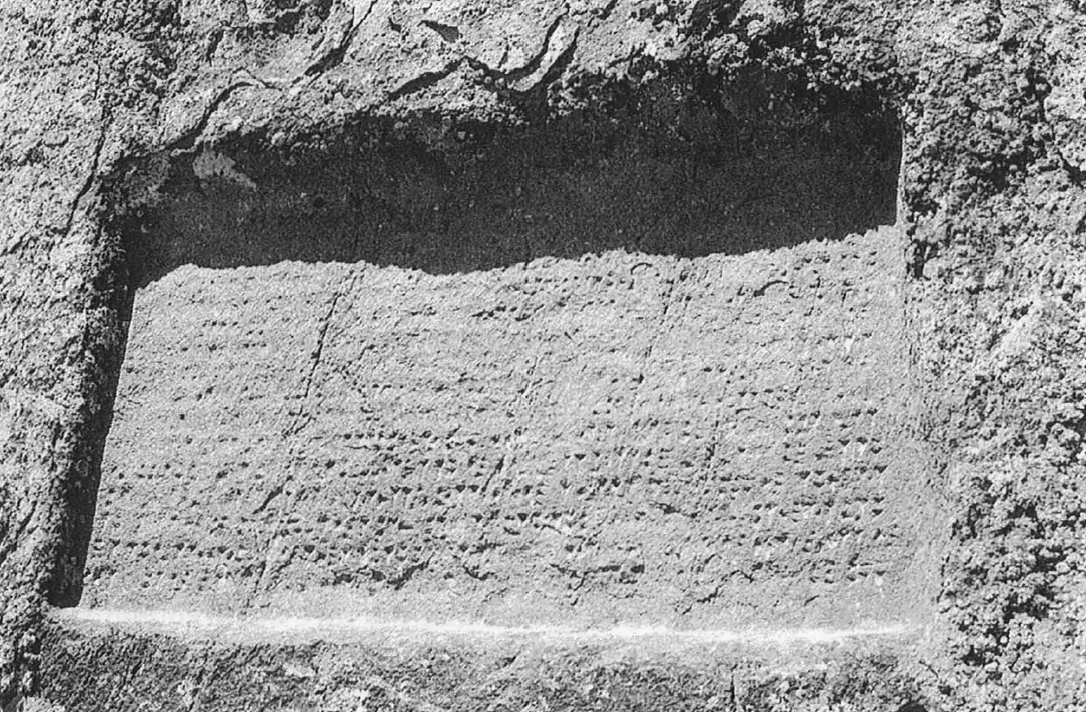

The tower of Gonbad-e Qābūs was commissioned by Shams al-Ma’āli Qabus ibn Voshmgir, a renowned Ziyarid ruler and patron of the arts. Shams al-Ma’āli, the greatest of the Ziyarids, was a man of letters and a scholar, author of several treatises on astrology and of poems in both Arabic and Persian. Built entirely in fired brick, the Gonbad-e Qābūs is the earliest and tallest surviving example of a monumental tomb with a double shell dome—a conical roof over an inner hemispherical dome (fig. 1). The tower has a circular plan, with the dome's radius measuring 4.8 m. The structure tapers slightly upward, taking the shape of a truncated pyramid with ten sides and a conical dome (fig. 2). Considering the 10-meter elevation of the mound on which the tower stands, the total height of the dome from the ground level reaches 62 meters. Two bands of Kufic inscriptions encircle the structure, naming its founder and recording the construction date as 397 H./A.D. 1006–1007. The inscription reads as follows:

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم - هذا القصر العالی الامیر شمسالمعالی - الامیر ابن الامیر - امر ببنائه فی حیاته - سنة سبع و تسعین - و ثلثمائة قمریة - و سنة خمس و سبعین - و ثلثمائة شمسیة

In the name of God the Merciful the Compassionate. This tall palace for Prince Shams al-Ma’ali, Amir Qābūs Ibn Voshmgir, was ordered to be built during his life, in the year 397 the lunar Hegira, and the year 375 the solar Hegira.

The interior is undecorated. There are no stairs, either inside or outside the structure, nor are there any indications of scaffolding or ladders ever being used, as there are no holes or marks to suggest their presence. The Russian excavations in 1899 revealed that 10.75 m. of the wall remained beneath the current interior ground level. However, the excavation did not reach the foundation platform. The German Orientalist Johannes Albrecht Bernhard Dorn refers to a fanciful account by the 16th-century Ottoman author Jannabi, who claimed that the body of Qābūs was placed in a glass coffin filled with aloe and suspended by chains from the dome of the mausoleum. In 1934, British traveler and writer Robert Byron visited the monument and repeated the legend that Qabūs’s body was placed in a crystal coffin, suspended by chains between the roof and floor of the tomb. This tale bears a striking resemblance to the one recorded by Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela about the Tomb of Prophet Daniel. Some have speculated that the origin of this legend can be traced back to Rabbi Benjamin’s account, though there is little substantial evidence to support this claim. The absence of a crypt or underground burial chamber lends some credence to this account. However, the actual location of Qābūs’ burial remains undiscovered.

Archaeological Exploration

The Qābūs has been a well-known monument since medieval times. Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Utbi, an Iranian historian of the eleventh century, reports that Qābūs’s tomb was in a “domed sepulcher outside Juzjan [Jurjan/ancient city of Gorgan], on the road to Khurasan” (Utbi, The Kitab-i-Yamini, p. 412). Ibn Isfandyar, a thirteenth-century Iranian historian and a native of Tabarestan (Mazandaran) writes that Qābūs “was buried beneath a dome outside Gurgan on the road to Khurasan” (Ibn Isfandyar, History of Tabaristan, p. 233). In modern times, the monument was first recorded and described by the British traveler, James Baillie Fraser, in 1826. Fraser writes that “the ruins of the ancient city of Jorjaun, together with a very singular and lofty tower, called by the people of the country Goombuz-e-Caoos, which were stated to be about two fursungs distant; the latter, indeed, was to be seen from the village rising above the intervening forests”. Fraser failed to recognize and identify the tower as the tomb of the renowned Ziyarid ruler but provided a vivid account of the monument’s structure and state of preservation. His narrative includes a fascinating story of its partial destruction (Fraser, Narrative of a Journey into Khorasan, pp. 613-614):

The tradition in the country relative to this partial dilapidation is as follows. They say that a certain king marching with his army in these plains, was asked by his officers where he would choose to halt at night; the tower still at a distance being in view, the king said that he should encamp at the foot of that tower, and not nearer. The deception of distance was so great, that the journey proved a very long and fatiguing one, and the king in anger swore the tower should never be the means of deceiving travellers again; so he ordered his miners to pull it down and destroy it. By the time, however, that they had proceeded so far as to effect the injury that still appears, the troops had encamped all around it, and the engineers desired to know his majesty's pleasure as to the quarter towards which they should cause the tower to fall: but the troops, and their tents and baggage swarmed on all sides, nor could they throw down the tower without destroying multitudes; so the monarch took further thought and ordered them to let it remain standing, in consideration of his army.

Fraser’s account of the tower’s demolition is thought to date back to the reign of Nadir Shah, as suggested by Baron Clement de Bode, who mentions the monument in the 1850s (Bode, “Quelques aperçus sur les Turcomans,” p. 41): “On assure que Nadir-Chah , dans un accès de colère, aurait donné l'ordre de l’abattre , mais que revenu à lui, il l’épargna.”

In 1882, the Russians occupied the region of Gorgan and established a base on top of the mound, aiming at controlling the customs and making the area secure. This was when the site was visited by a British traveler, Colonel Charles Edward Yates, in 1895. Four years later, in 1899, General Poslavski conducted excavations in an attempt to locate Qābūs’s tomb, though with little success. Poslavski published the first detailed description of the tower with its dimensions in 1900. However, according to Mohammad Ali Qūrkhanechi (Solat Nezam), an Iranian border officer in the region in 1903, the Russians may have discovered a secret passage to the tomb.

In 1908, Sir Percy Sykes visited the monument published a description of it, and reproduced a picture of the tower in his History of Persia. Sykes complained about the damages as follows (Sykes, “A Sixth Journey,” p. 14):

Sad to say, the bricks round the base of this fine building, which is also a wonderful landmark, have been extracted, and, unless the Russian Commissioner executes the necessary repairs, this historical edifice, with an authentic history of nearly one thousand years, may soon be a shapeless mass of bricks, and might quite possibly destroy the Commissioner's house situated close to its southern side, in its fall.

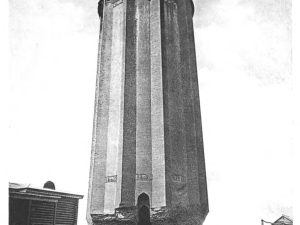

Between 1911 and 1913, the French art historian and traveler, Henry Viollet visited the Gonbad-e Qābūs and took the first detailed photographs of the tomb tower (figs. 3 and 4). In February 1913, Ernst Diez, the renowned Austrian art historian, traveled to the region and published a thorough study of the Gonbad-e Qābūs. In 1921, the Russian scholar and Orientalist Vasili Barthold published a brief article on the Gonbad-e Qābūs, drawing comparisons with the tower known as Mil-e Rādkān. By the time Robert Byron visited the monument in 1934 and photographed it, the original Russian structures had been replaced by an Iranian gendarmerie outpost. This new installation featured a rectangular, fortified mud-brick compound, dominated by a central tower that served as its focal point (fig. 5) The most comprehensive study of the monument to date was conducted by André Godard, who served as the head of the Iranian Archaeological Department and the Archaeological Museum and was published in 1938.

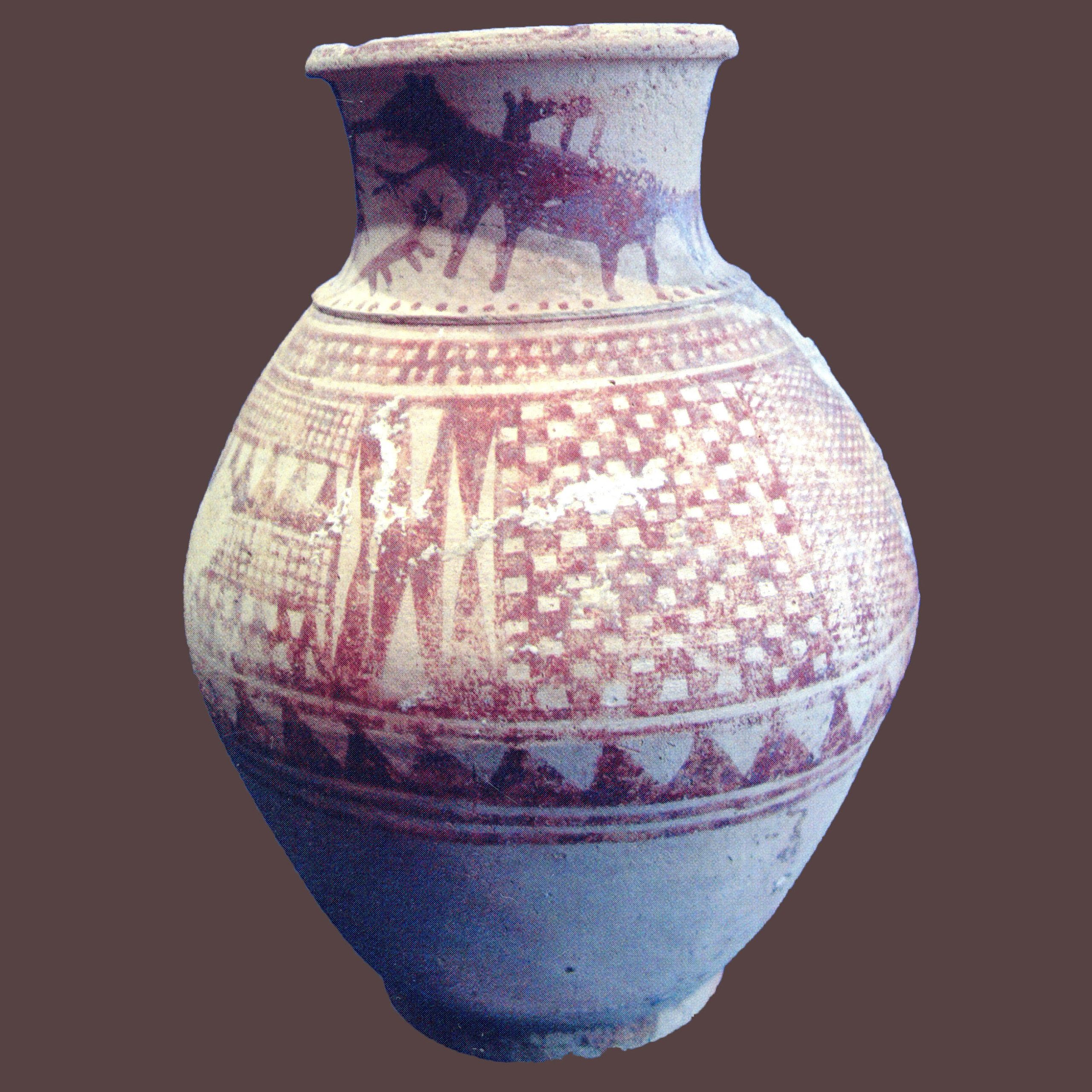

The base of the tower suffered significant damage from treasure hunters and individuals scavenging for fired bricks (fig. 6). Their actions severely compromised the lower section of the wall, to the extent that, despite the base course being 4 m. thick, it was on the brink of collapse in some areas, particularly near the entrance. The conical dome was also largely damaged on its eastern and western sides, with hundreds of its deeply set bricks broken and dislodged due to the gunfire. The area surrounding the eastern opening had been destroyed. In the early 1920s, the Iranian Department of Archaeology carried out an emergency restoration work to prevent the complete collapse of the monument. In 1939, under the sponsorship of the Iranian Department of Archaeology, the archaeologist Nosratollah Meshkati undertook a more substantial restoration project. Some reports in Persian refer to another series of restoration work conducted at the base of the tower in 1961. The last, more substantial restoration activities were completed in the early 1990s. In 2009, on behalf of the local office of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi and Ghorbanali Abbasi carried out a stratigraphic excavation at the Gonbad-e Qābus mound. The results show that the mound contains a long sequence of archaeological layers, spanning from the late Iron Age period (c. 800-600 B.C.) to the tenth century. In 2012, the Gonbad-e Qābūs was inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.

Fig. 3. The view of the Gonbad-e Qābūs in 1913 (image: Fonds Henry Viollet, BULAC, Paris, HV610. © Maria Lavabre Viollet / CeRMI – UMR8041 du CNRS)

Fig. 4. The view of the Gonbad-e Qābūs in 1913 (image: Fonds Henry Viollet, BULAC, Paris, HV605. © Maria Lavabre Viollet / CeRMI – UMR8041 du CNRS)

Fig. 5. Robert Byron’s photograph of the Gonbad-e Qābūs in 1934 (image: Archnet.org/collection, image 08575)

Fig. 6. Gonbad-e Qābūs in 1913 (image: Diez, Churasanische Baudenkmäler, p. 144, pl. 4).

Bibliography

Barthold, V. V., “Bashnia Kabusa kak pervyi datirovannyi pamiatnik musul’manskoi persidskoi arkhitektury,” Ezhegodnik Rossiiskogo instituta istorii iskusstv/Annales de l’Institut russe d’histoire de l’art, tome 1, fascicule 2, Petersbourg, 1921, pp. 121-125.

Blair, Sh., The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana, Leiden, 1992, no. 19, pp. 63-65.

Blair, Sh., “Gonbad-e Qābus, iii. Monument,” Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_2320

Bode, A. C. de, “Quelques aperçus sur les Turcomans à l’orient de la mer caspienne: les Yamouds et les Goklans,” Nouvelles Annals des Voyages et des Sciences géographiques, Nouvelle série, tome 30, 1852, pp. 42-43.

Bosworth, C. E., “Kabus b. Wushmagir b. Ziyar,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, second edition, vol. III, pp. 357-358.

Byron, R., The Road to Oxiana, New York, reprint, 1982, p. 201.

Diez, E., Churasanische Baudenkmäler, Berlin, 1918, pp. 39-43.

Dorn, J. A. B., “Caspia. Über die Einfälle der alten Russen in Tabaristan , nebst Zugaben über andere von ihnen auf dem Kaspischen Meere und in den anliegenden Ländern ausgeführte Unternehmungen,” Mémoires de l’Académie impériale des sciences de Saint-Pétersbourg, VII series, vol. XXIII, Part I, St. Petersburg, 1875, p. 91.

Fraser, J. B., Narrative of a Journey into Khorasān in the Years 1821 and 1822, London, 1825, pp. 612-615.

Ibn Isfandyar, Muhamad ibn Hasan, An Abridged Translation of the History of Tabaristan Compiled about A. H. 613 (A. D. 1216), edited by E. G. Browne, Leiden and London, 1905, pp. 225-234, 412.

Levy, R., A Mirror for Princes. The Qabus Nama, by Kai Ka’us ibn Iskandar Prince of Gurgan, translated from the Persian by Rueben Levy, New York, 1951, p. xi.

Meshkati, N., “Jorjan - Gonbad-e Qabus,” Honar va Mardom, vol. 5, No. 51, 1345 H./1967, pp. 33-39 (in Persian).

Qūrkhanechi, M. A., Nokhbe-ye seyfiy-eh, edited by M. Etehadiyeh and C. Sa’advandian, Tehran, 1360H./1981, pp. 54-55.

Sykes, P. M., “A Sixth Journey in Persia,” The Geographical Journal, vol. 37, No. 1. 1911, pp. 1-19.

Sykes, P. M., A History of Persia, vol. 2, London, 1915, p. 92.

Yates, C. E., Khurasan and Sistan, London, 1900, p. 240.