Gonbad-e Kabūdگنبد کبود

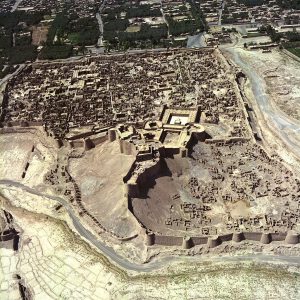

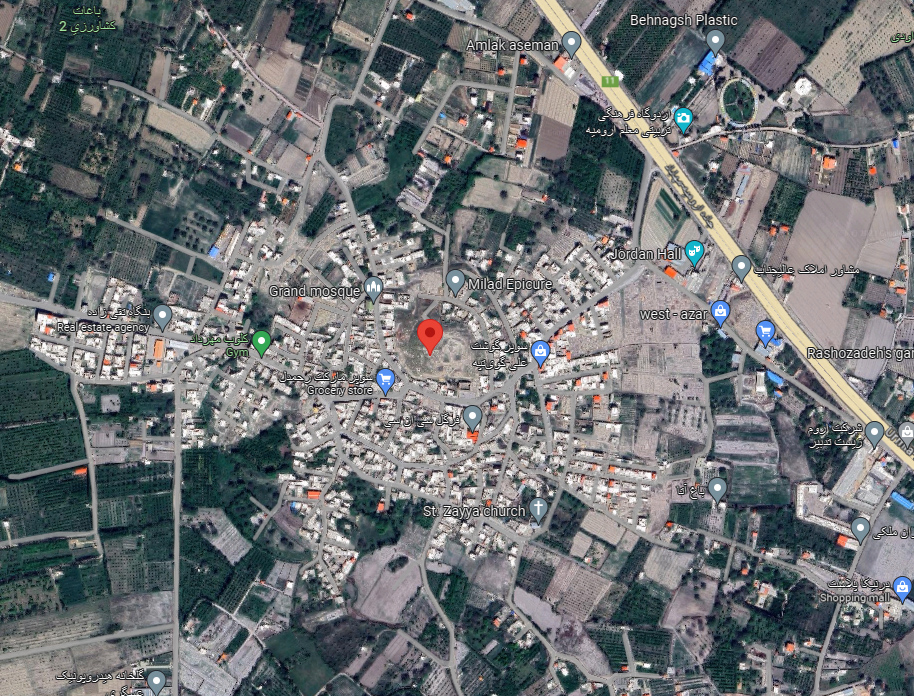

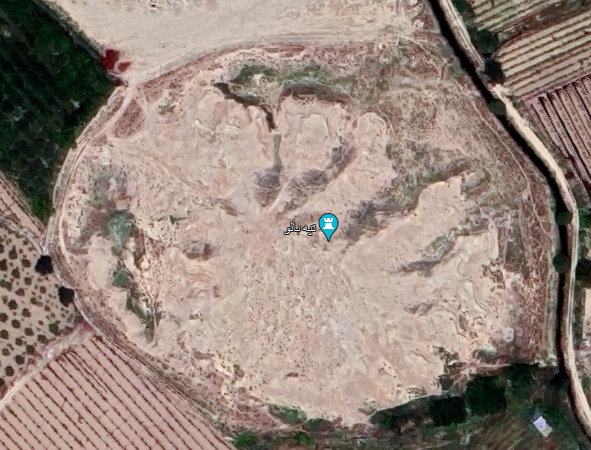

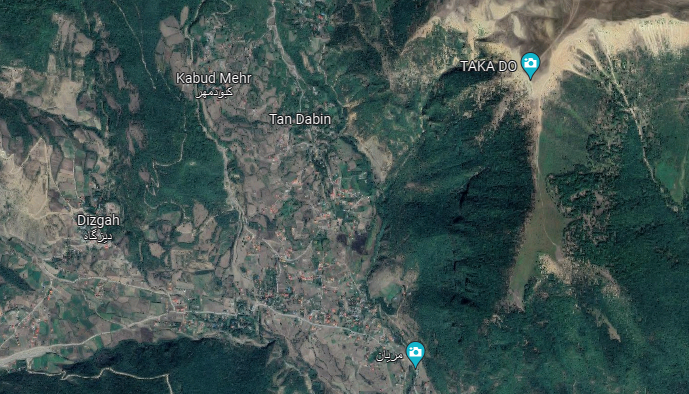

Location: The Gonbad-e Kabūd is located in Marāgha, northwestern Iran, East Azarbaijan Province.

37°23’24.9″N 46°14’21.5″E

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

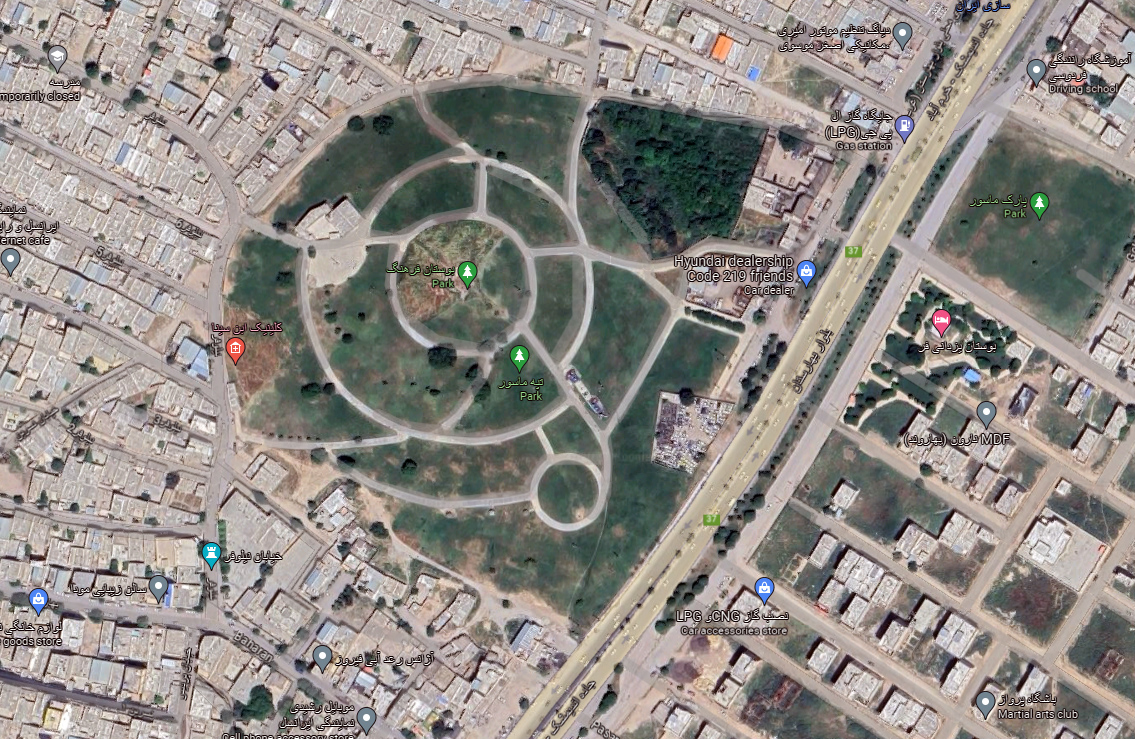

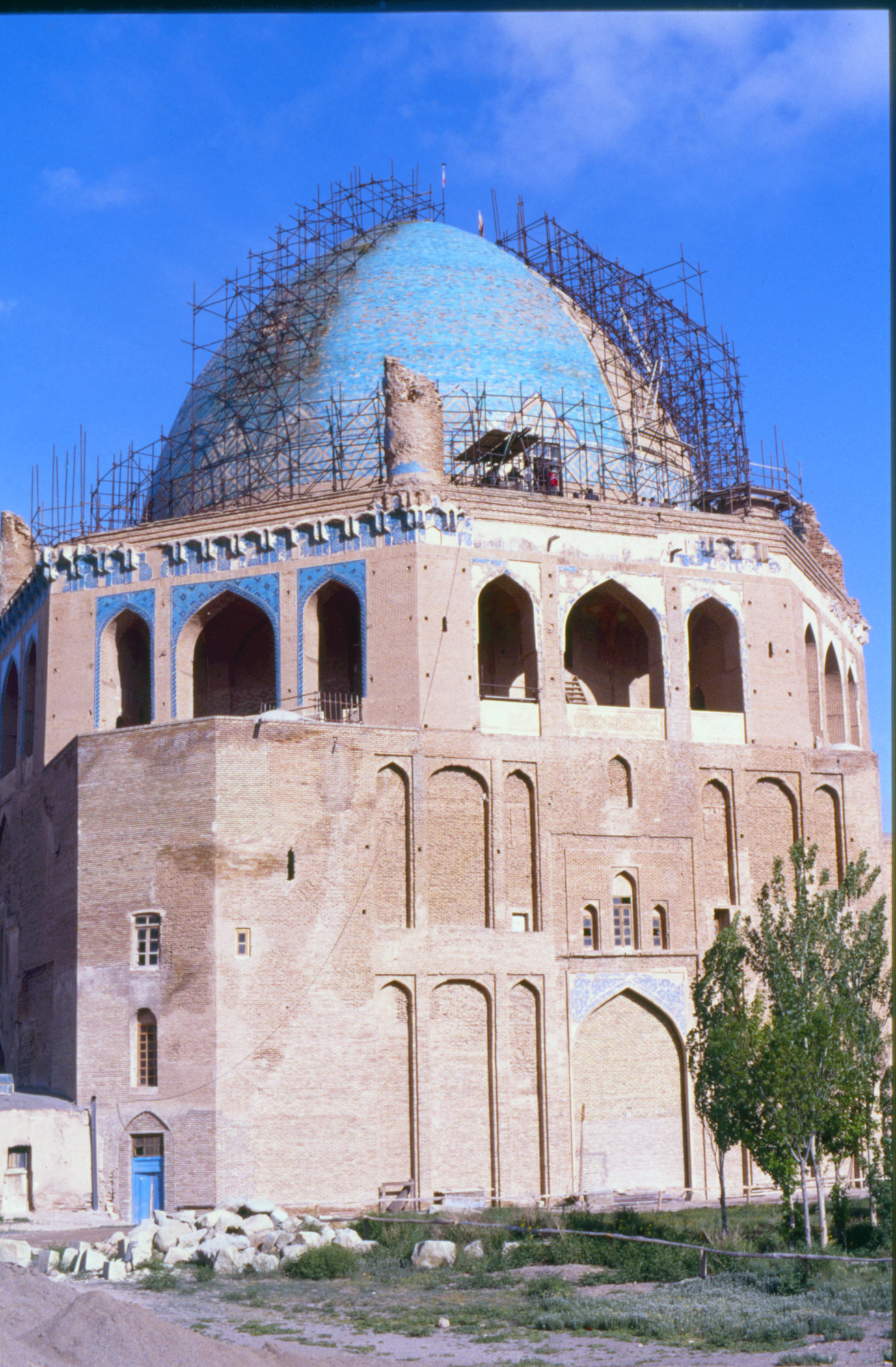

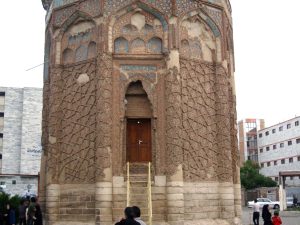

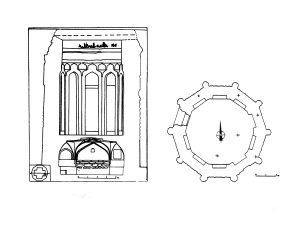

The Gonbad-e Kabūd (Blue Dome) (fig. 1) is a decagonal tomb tower over 14 meters in height, built of fired brick upon a stone foundation, located in the center of the present town of Marāgha. Set upon a base roughly two meters high, constructed from precisely coursed ashlar blocks and incorporating a modest pointed-arch portal, the tower ascends to a height of about ten meters. At each corner, rounded masonry buttresses emerge (fig. 2), projecting nearly three-quarters of their full form and extending seamlessly beyond the base course down to the very ground, lending the structure both stability and a sense of sculptural rhythm.

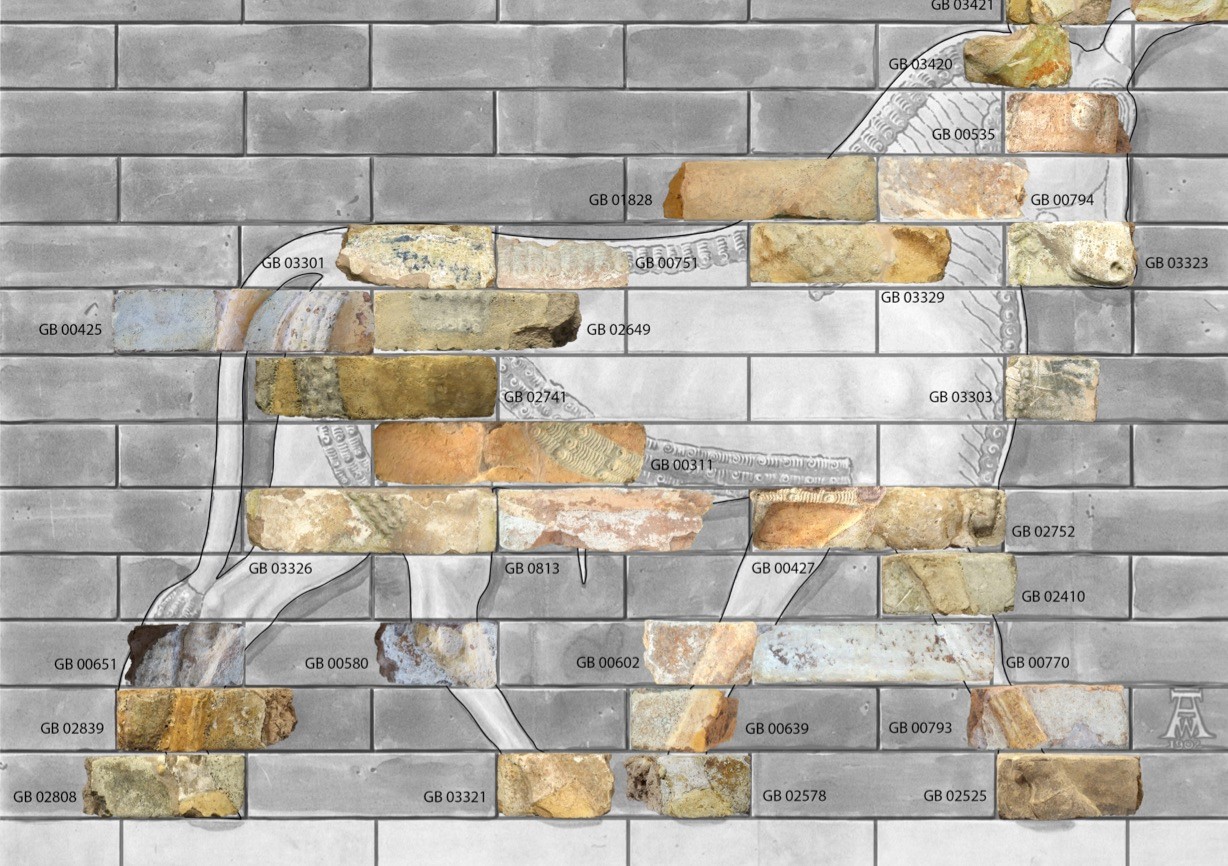

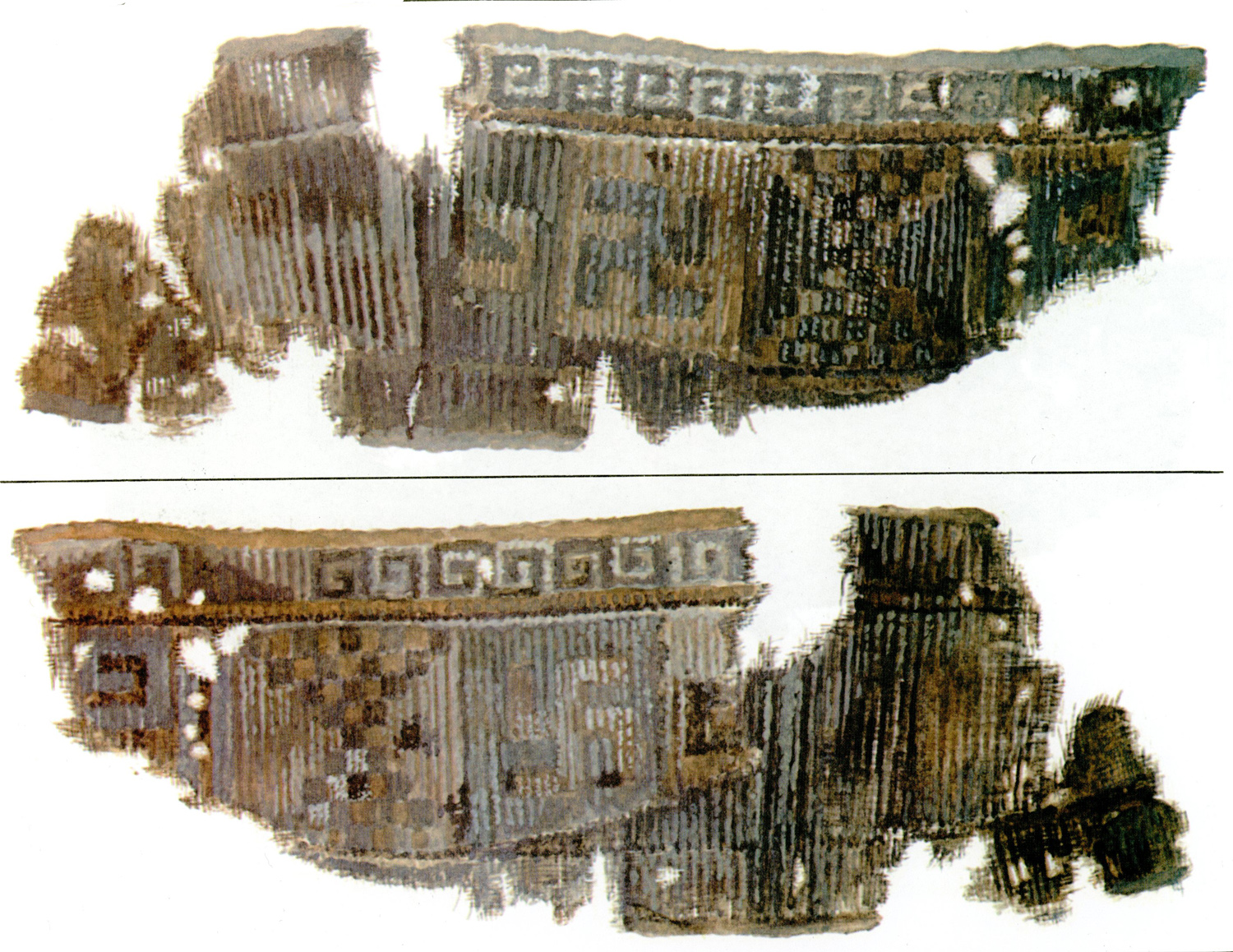

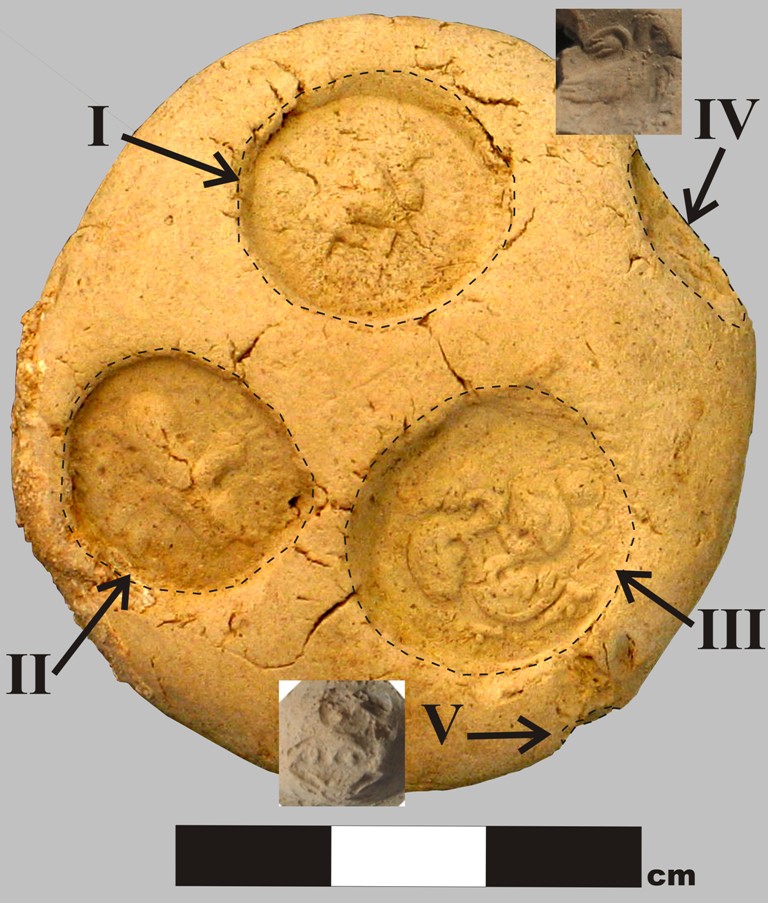

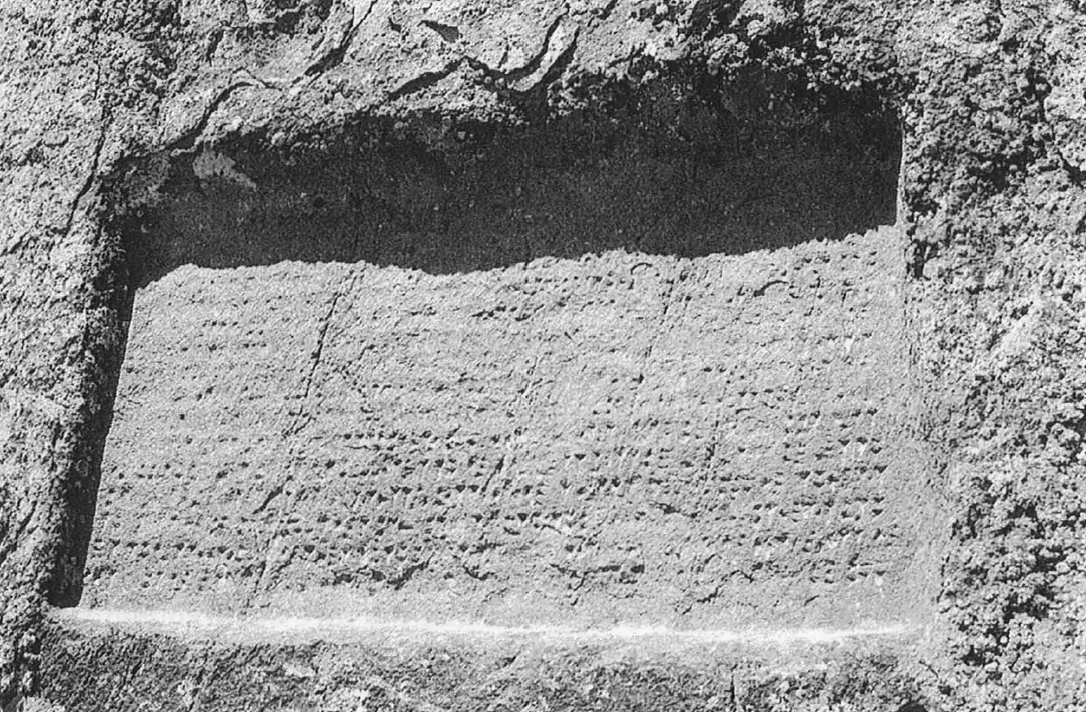

It is unknown precisely to whom this tower was dedicated, as its dedicatory inscription is very poorly preserved, and the tombstone, which would have been housed within the crypt, has since disappeared. As the name suggests, this tower has been popularly associated with the mother of the Mongol Ilkhān, Hülegü, Sorghaghtani Beki (ca. A.D. 1190-1252). However, this association has been disproved by André Godard through stylistic similarities with the Mū’mene Khātūn mausoleum in Nakhchivan (dated 582 H./A.D. 1186-7); the presence of various Quranic inscriptions on the monument; and the negative impressions left by the enameled letters of the dedicatory inscription (fig. 3), which permit a reconstruction of the dating formula as “year 593 (A.D. 1197/98).

The Gonbad-e Kabūd stands out amongst Saljuk tomb towers for its decagonal plan, shared only by the Mū’mene Khātūn tower in Nakhchivan; the interior chamber of the neighboring Circular Tomb at Marāgha; and the Mausoleum of Kilij Ārslān II (1156-1192 A.D.) in Konya. Like the Mausoleum of Kilij Ārslān II and the Mū’mene Khātun, it originally had a 10-sided polyhedral dome, covered in blue faience tiles, and an inner dome, likely hemispherical in shape, but only the base of the outer dome is preserved. The engaged columns on each of the corners, fully covered in strapwork decoration with no break in the pattern, also show influence from both the Mū’mene Khātūn tower and the twin towers at Kharraqān (ca. 460 H./A.D.1067-8 and 486 H./A.D. 1093). It is also notable for its use of mosaic faience decoration, used to pick out the geometrical strapwork decoration of its sides, the muqarnas molding beneath the dome, and its exterior Kufic inscriptions. In this, it follows the tradition of the Gonbad-e Sōrkh and Mū’mene Khātun, and innovates upon these monuments, demonstrating a new technique in which the both geometrical patterns and Arabic inscriptions were incised in rectangular glazed plaques, leaving the voids of the patterns in unglazed fired brick.

Based on this dating, this tower is the latest of a series of three tombs in Marāgha built under the Ahmadili Atabegs (1122-1225 A.D.), along with the Gonbad-e Sorkh (ca. 542 H/A.D. 1147-8) and the Circular Tomb (ca. 563 H./A.D. 1167-8).

In addition to its dedicatory inscription, of which little has been preserved, this tower contains many Quranic inscriptions. One of the most significant inscriptions related to the geometric pattern of the tower is located near the upper chamber of the tower, below the interior dome; it runs as a long band in white plaster, rendering Sura 67, verses 1-4 in naskhi script (fig. 4):

تَبَـٰرَكَ ٱلَّذِى بِيَدِهِ ٱلْمُلْكُ وَهُوَ عَلَىٰ كُلِّ شَىْءٍۢ قَدِيرٌ

ٱلَّذِى خَلَقَ ٱلْمَوْتَ وَٱلْحَيَوٰةَ لِيَبْلُوَكُمْ أَيُّكُمْ أَحْسَنُ عَمَلًۭا ۚ وَهُوَ ٱلْعَزِيزُ ٱلْغَفُورُ

ٱلَّذِى خَلَقَ سَبْعَ سَمَـٰوَٰتٍۢ طِبَاقًۭا ۖ مَّا تَرَىٰ فِى خَلْقِ ٱلرَّحْمَـٰنِ مِن تَفَـٰوُتٍۢ ۖ فَٱرْجِعِ ٱلْبَصَرَ هَلْ تَرَىٰ مِن فُطُورٍۢ

ثُمَّ ٱرْجِعِ ٱلْبَصَرَ كَرَّتَيْنِ يَنقَلِبْ إِلَيْكَ ٱلْبَصَرُ خَاسِئًۭا وَهُوَ حَسِيرٌۭ ٤

“In the name of God, most gracious, most merciful! Blessed be He in Whose hands Is Dominion; And He over all things hath Power;

He Who created Death and Life, that He may try which of you is best in deed: And he is the Exalted in Might, Oft-Forgiving. He Who created the seven heavens one above another;

No want of proportion wilt thou see in the Creation of (God) Most Gracious. So turn thy vision again: Seest thou any flaw?

Again turn thy vision a second time: [it] will come back to thee dull and discomfited, in a state worn out.”

(tr. Bier “Geometry made manifest Reorienting the historiography of ornament on the Iranian plateau and beyond,” p. 62)

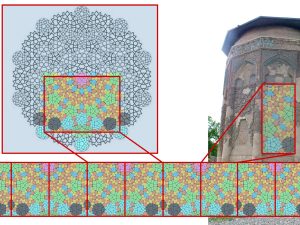

The most innovative feature of this monument is its geometrical decoration, which reaches a new level of sophistication in late-Seljuk decorative art. The ‘ornamental band’ (fig. 5) of this tower, an unglazed cut brick design, covering all sides of the monument except the entrance, repeats a patch of the first man-made quasiperiodic structure across every two sides of the tower. The quasiperiodic pattern covers the plane in an ordered and infinite way, as ordinary crystals do, but lacks translational symmetry, meaning that no two sections of the pattern are completely alike. This pattern does allow rotational symmetry, meaning that parts of the pattern can be rotated to fit exactly on other parts, but contains pentagons and decagons, forbidden by traditional crystalline structures. These patterns were first discovered by mathematician Roger Penrose in 1975. Moreover, the discovery of similar patterns in nature by Dan Schechtman in 1982 caused a paradigm shift in the study of Crystallography (Penrose “The role of aesthetics in pure and applied mathematical research”; Schechtman et al. “Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry”). The discovery of such patterns in late Seljuk art dramatically changes our understanding of the mathematical sophistication present during that historical period. The rest of the geometrical decoration of the tower is scarcely less fascinating, with the upper spandrels of the niches on each face containing a pattern with two layers of polygonal nets in glazed and unglazed brick, forming a design of interlacing five-, six- and seven pointed stars (fig. 6); and the lower spandrels including an unglazed design of eight-, nine- and ten-pointed stars (fig. 7).

Considering the patterns of the Gonbad-e Kabūd in the context of the sophisticated geometrical metaphors of contemporary Persian poetry (i.e. Niẓāmī Ganjavī’s Haft Paykar), along with the geometrical model of the universe outlined in the Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity) demonstrates the degree of interaction between geometry, poetry and philosophy in this period (Bier “Geometry made manifest Reorienting the historiography of ornament on the Iranian plateau and beyond”; Howley, “Geometric Structures and Invertiling in the Poetry of Niẓāmī’s Haft Peykar”).

Based on a recent study, the geometric patterns may reveal the influence of the Ikhwān al-Safa’s ideas on the Gonbad-e Kabūd's motifs. The Rasa’il Ikhwan al-Safa (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity) represent the most complete and significant source on the relationship between theory and practice, particularly regarding their impact on Iranian arts and crafts of the Islamic period in the 4th century (10th century A.D.). The direct connection between the Ikhwān al-Safa’s reflections and the geometric patterns of the tomb tower is, however, not unknown. It seems that the architects and artists working on the Gonbad-e Kabūd tower had rather an unconscious, intuitive understanding of them.

Fig. 1. Gonbad-e Kabūd, northwestern side with the entrance (image: Archnet, Creative Commons)

Fig. 2. Gonbad-e Kabūd. Ground plan and section (after Daneshvari, Medieval Tomb Towers of Iran, fig. 14).

Fig. 3. Partial reconstruction of the Gonbad-e Kabūd’s dedicatory inscription, including the dating formula (after Godard, “Notes Complementaires sur les Tombeaux de Maragha,” p. 143, fig. 99).

Fig. 4. Exterior kufic inscription below the cornice, quoting Quran Sura 2, verse 255, or Sura 2, verse 26 (image: Archnet.org).

Fig 5. The author’s tile analysis of the ‘Ornamental Band’ of the Gonbad-e Kabūd, based on Makovicky, “800-year-old Pentagonal Tiling from Marāgha, Iran, and the new varieties of Aperiodic Tiling it inspired,” and Ajlouni, “The Long-Range Global Order of Quasi-Periodic Patterns in Islamic Architecture”.

Fig. 6. Tile analysis of the upper spandrels of the Gonbad-e Kabūd’s niches, based on Wilber, “The Development of Mosaic Faience,” p. 39, fig. 17 (image: Archnet.org).

Fig. 7. The author’s tile analysis of the lower spandrels in the niches of the Gonbad-e Kabūd (image: Archnet.org)

Archaeological Exploration

The first photograph of the tomb tower was taken in the 1880s by an Iranian photographer of the Qajar period (fig. 8). The first traveler referring to the Gonbad-e Kabūd is Anton Houtum-Schindler, who, during his 1882 visit, attributed the tomb-tower to one of the wives of Hülegü. A few years later, in his Mission scientifique en Perse (1889), Jacques de Morgan published the first known photograph of the Gonbad-e Kabūd. In the accompanying text, he described the monument as the tomb of Hülegü’s mother, while the caption beneath the image identified it instead as the resting place of the Ilkhan’s daughter. In the early years of the twentieth century, Friedrich Sarre studied the monument in detail and published a better photograph of it in his Denkmäler persischer Baukunst.

In 1933, Robert Byron visited the monument and described it in his romantic and eloquent style (Byron, The Road to Oxiana, pp. 55-56):

“…a fine polygonal grave-tower of the XIIth century, which is known as the grave of the Mother of Hulagu and is built of plum-red brick arranged in patterns and inscriptions. The effect of this cosy old material, transferred as it were from an English kitchen-garden to the service of Koranic texts, and inlaid with glistening blue, is surprisingly beautiful. There is a Kufic frieze inside, below which the walls have been lined with nesting-holes for pigeons…”

The earliest detailed study of this monument is that of André Godard, for his 1934 publication Les Monuments de Marāgha. In this publication, he refutes the association with the mother of Hülegü Khān, based on the presence of Quranic inscriptions on the tower, and stylistic comparisons with monuments of the Mongol period and the Mū’mene Khātun, and also suggests an association with the fifth Ahmadili Atabeg, ‘Ala al-Dīn Körp Arslān (ca. 585? -604 H./A.D.1189?-1208) (Godard, Les Monuments de Marāgha, pp.7-11). He added to this in his 1936 article, “Notes Complémentaires sur les Tombeaux de Marāgha” in the first volume of Athār-é Īrān: Annales du Service Archéologique de l’Īrān, in which he restated his previous claims, and presented his reconstruction of the dedicatory inscription, based on a more thorough investigation of the monument in a 1936 expedition to Iranian Azerbaijan. In 1937, Myron Bement Smith visited the tower and made a detailed study, producing structural drawings (fig. 8) and various black and white photographs. He also acquired negatives of earlier photographs of the monument by Antoin Sevruguin (ca. A.D. 1851–1933), providing an invaluable record of the tower in a better state of preservation. Smith was the first to draw a sketch plan of the tower. In the 1930s, the Iranian Archaeological Office undertook emergency restoration work to consolidate the structure. In 1978, the Iranian Office for the Conservation and Restoration of Historical Monuments covered the tower’s ruined dome with a galvanized metallic roof to protect it from further deterioration. The roof was removed in 2018 to be replaced by a fully restored dome. Two seasons of excavations were carried out in the vicinity of the tower in 2001 and 2018 on behalf of various Iranian institutions. The published results show the existence of a third circular tower, now destroyed, in the proximity of the present-day standing towers.

Bibliography

Ajlouni, R. A., “The Long-Range Global Order of Quasi-Periodic Patterns in Islamic Architecture,” Acta Crystallographica, Section A: Foundations of Crystallography, vol. 68, no. 2, 2012, pp. 235-43.

Ashtiani, H. and S. Moradzadeh, “Barresi-ye ara’i Ikhvān al-Safa dar mored-e elm-e adad va hendesa. Motāle-ye moredi-ye taz’ināt-e va naqshmāyehā-ye Gonbad-e Kabūd, Maragha,” Me’mārishenāsi, No. 13, 1398/2019, pp. 1-13.

Bier, C. “Geometry made manifest: Reorienting the historiography of ornament on the Iranian Plateau and Beyond,” The Historiography of Persian Architecture, edited by M. Gharipour, London, 2016, pp. 41-79.

Bier, C., “Taking Sides, but Who’s Counting? The Decagonal Tomb Tower at Maragha,” Bridges Conference: Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, Science, edited by R. Sarhangi, et al., Phoenix, 2011, pp. 497-500.

Bier, C., “The Decagonal Tomb Tower at Maragha and Its Architectural Context: Lines of Mathematical Thought.” Nexus Network Journal, vol. 14, 2012, pp. 251-273.

Byron, R., The Road to Oxiana. London, 1937.

Daneshvari, A., “Complementary Notes on the Tomb Towers of Medieval Iran. 1: The Gunbad-i Kabud at Maraghe 593/1197,” Art et société dans le Monde iranien, edited by C. Adle, Paris, 1982, pp. 287-295.

Daneshvari, A., Medieval Tomb Towers of Iran. Malibu, 1986.

Godard, A., Les monuments de Marāgha, Paris, 1934, pp. 7-11, figs. 5-6.

Godard, A., “Notes complémentaires sur les tombeaux de Maragha,” Athar-e- Iran, vol. 1, 1936, pp. 138-143.

Godard, A., L’art de L’Iran, Paris, 1962, p. 366.

Houtum-Schindler, A., “Reisen im nordwestlichen Persien 1880-82,” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, vol. 18, 1883, p. 338.

Howley, C., “Geometric Structures and Invertiling in the Poetry of of Niẓāmī’s Haft Peykar,” Symmetry: Art and Science, vols. 1-4, 2025.

Lu, P. J. and Steinhardt, P.J., “Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture,” Science, vol. 315, 2007, pp. 1106-1110.

Makovicky, E., “800-Year-Old Pentagonal Tiling from Maragha, Iran, and The New Varieties of Aperiodic Tiling It Inspired.” in Fivefold Symmetry, I. Hargittai (ed.), Singapore, 1992, pp. 67-86.

Morgan, J. de, Mission scientifique en Perse, vol. 1, Paris, 1889, pl. XXXVII.

Myron Bement Smith Collection, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. Gift of Katharine Dennis Smith, 1973- 1985.

Sarre, F., Denkmäler persischer Baukunst, Berlin, 1910, p. 15, fig. 10.

Wilber, D., “The Development of Mosaic Faience in Islamic Architecture in Iran,” Ars Islamica vol. 6, 1939, pp. 37-39.