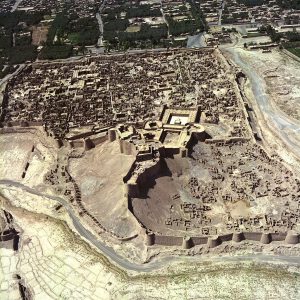

Geoy Tepe/Gük Tepeگوی تپه/ گوک تپه

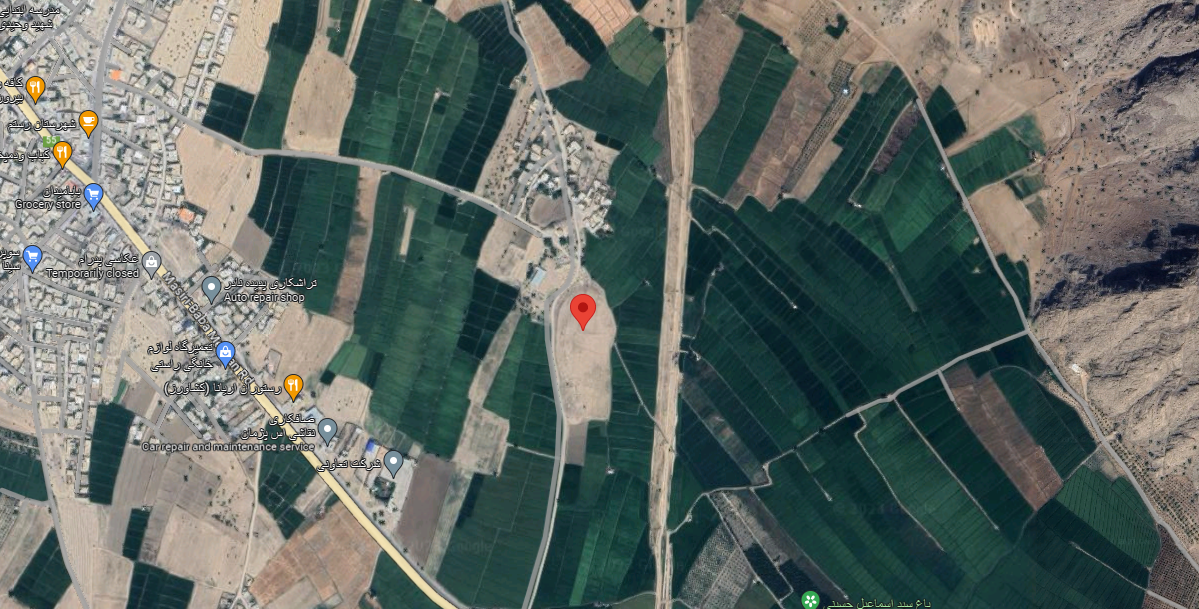

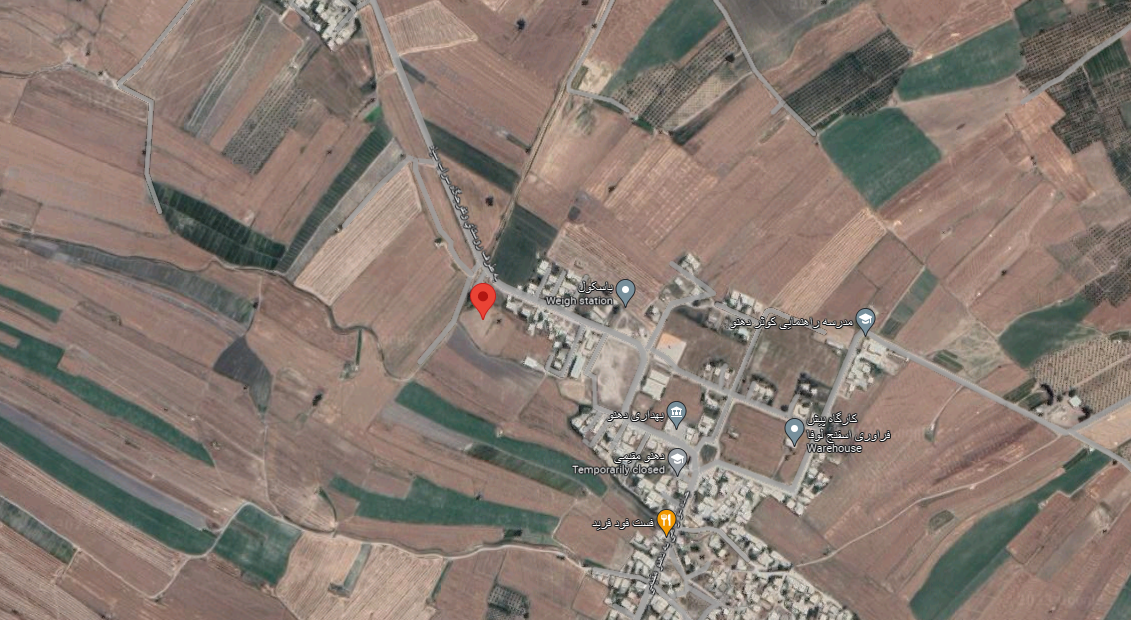

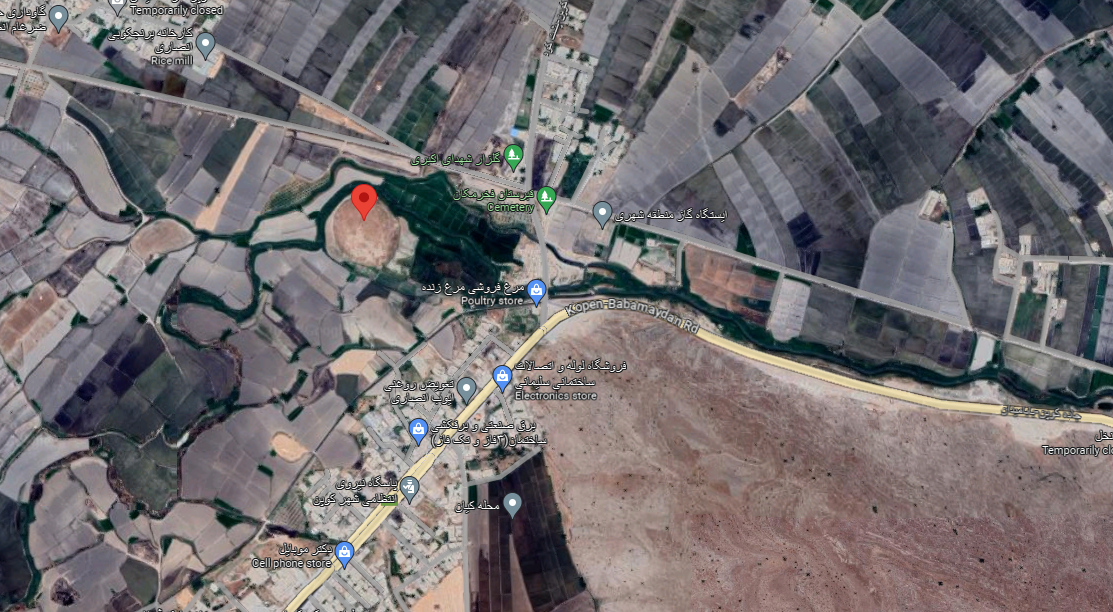

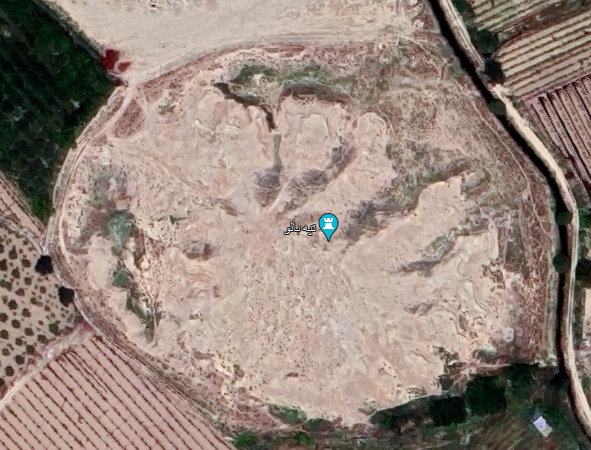

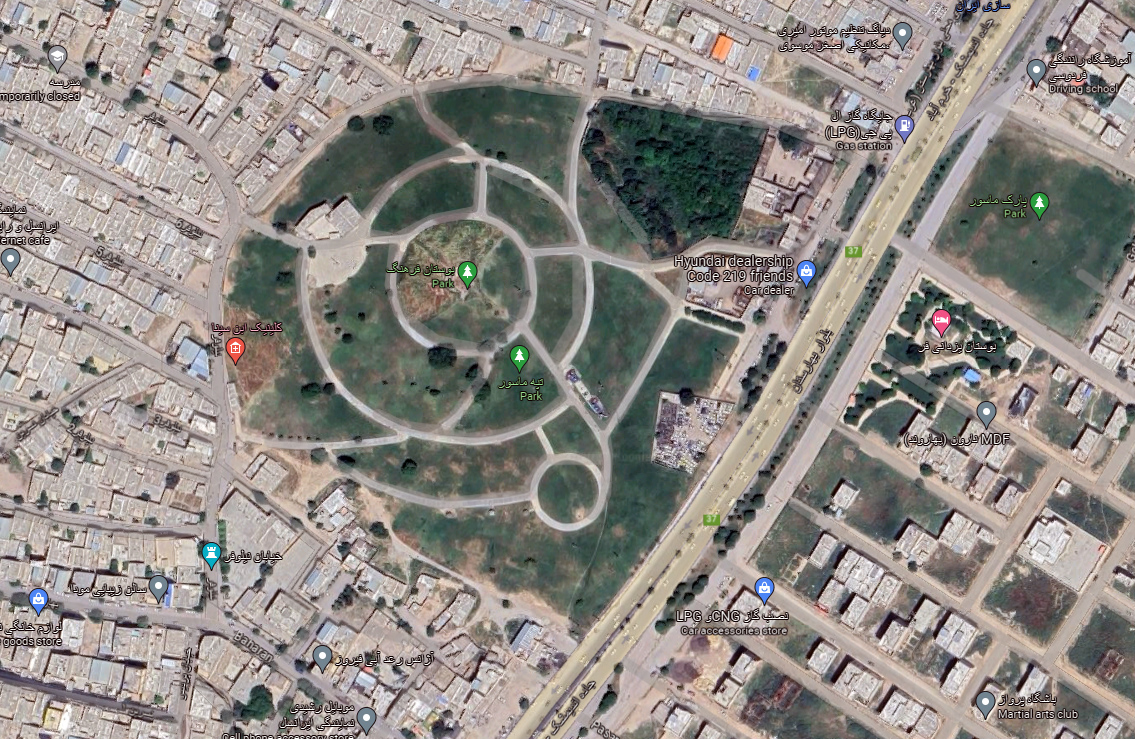

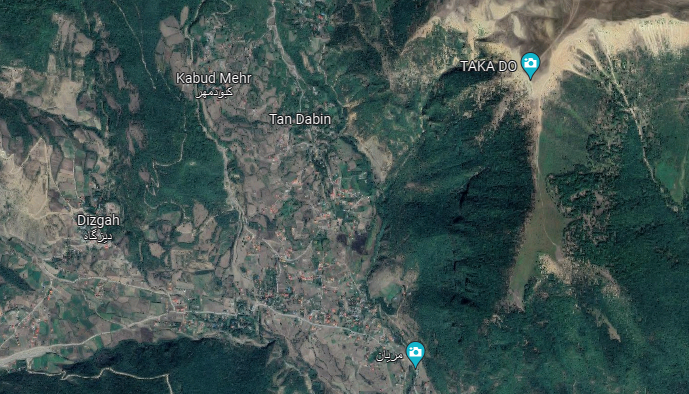

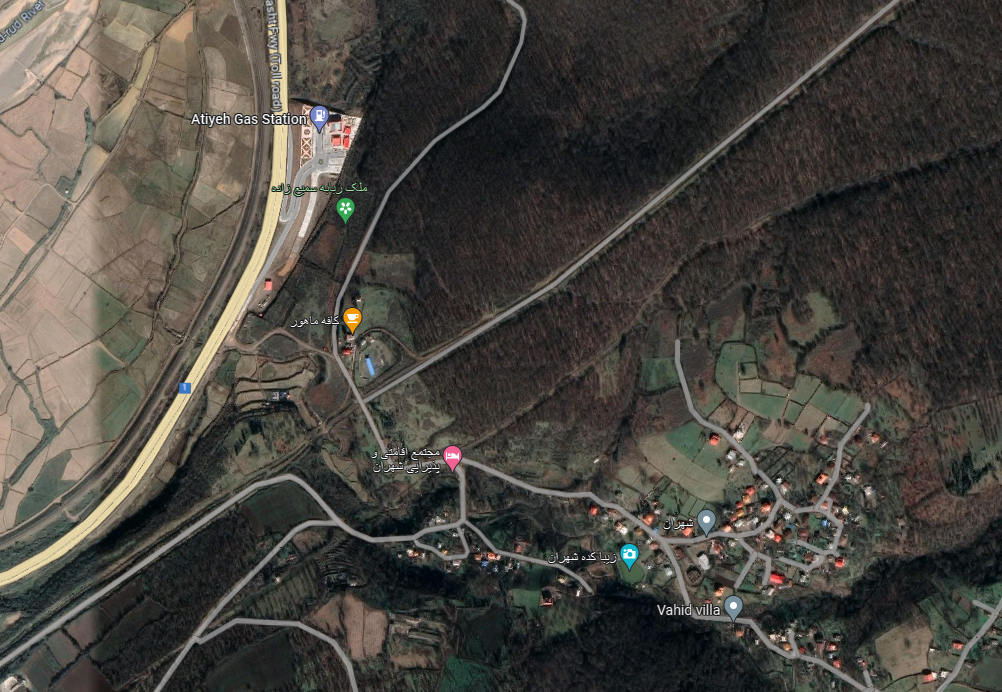

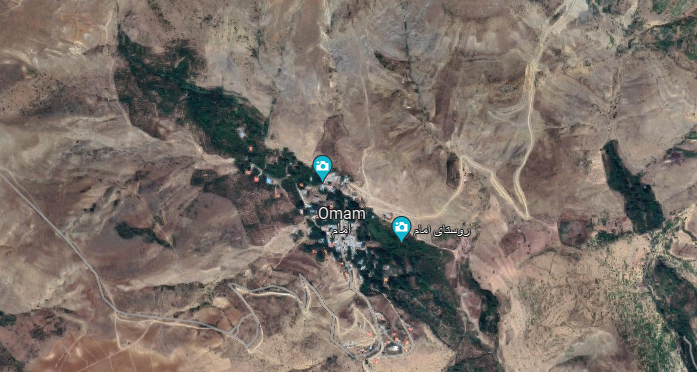

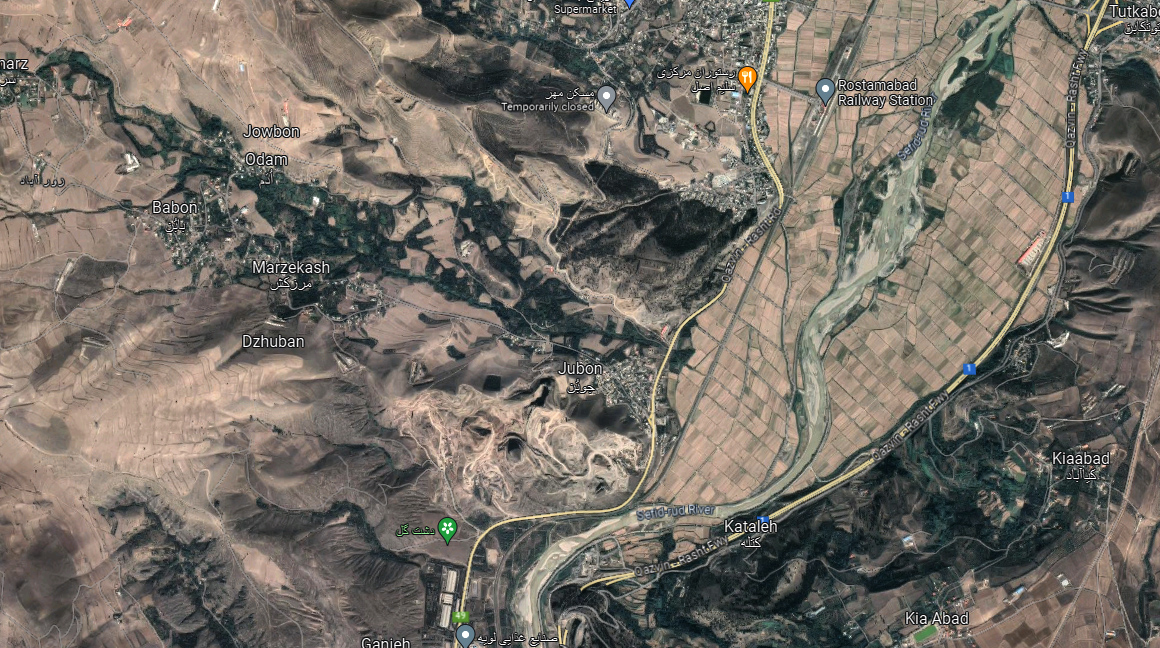

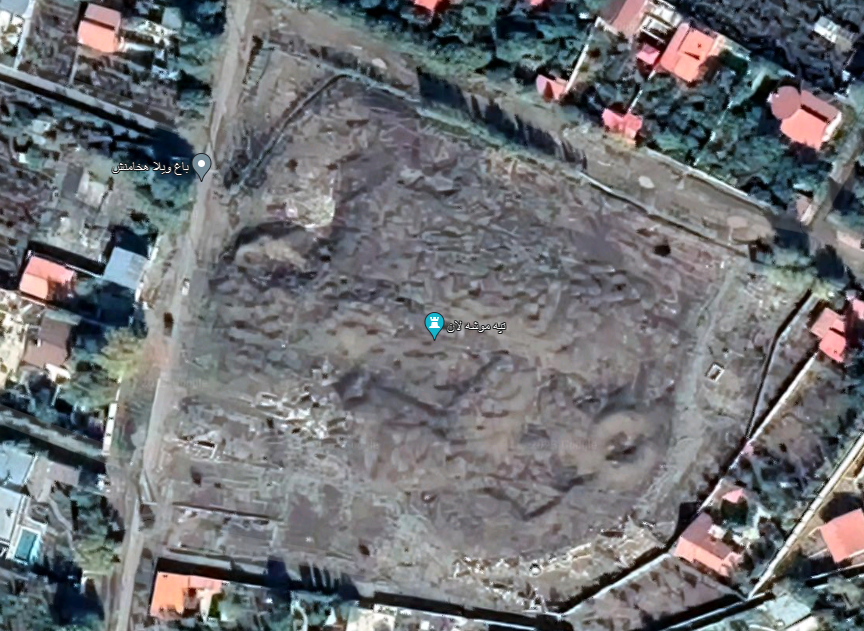

Location: Geoy Tepe is located southeast of Urmia, in northwestern Iran, West Azerbaijan Province.

37°31’04.4″N 45°08’41.5″E

Map

Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age

History and description

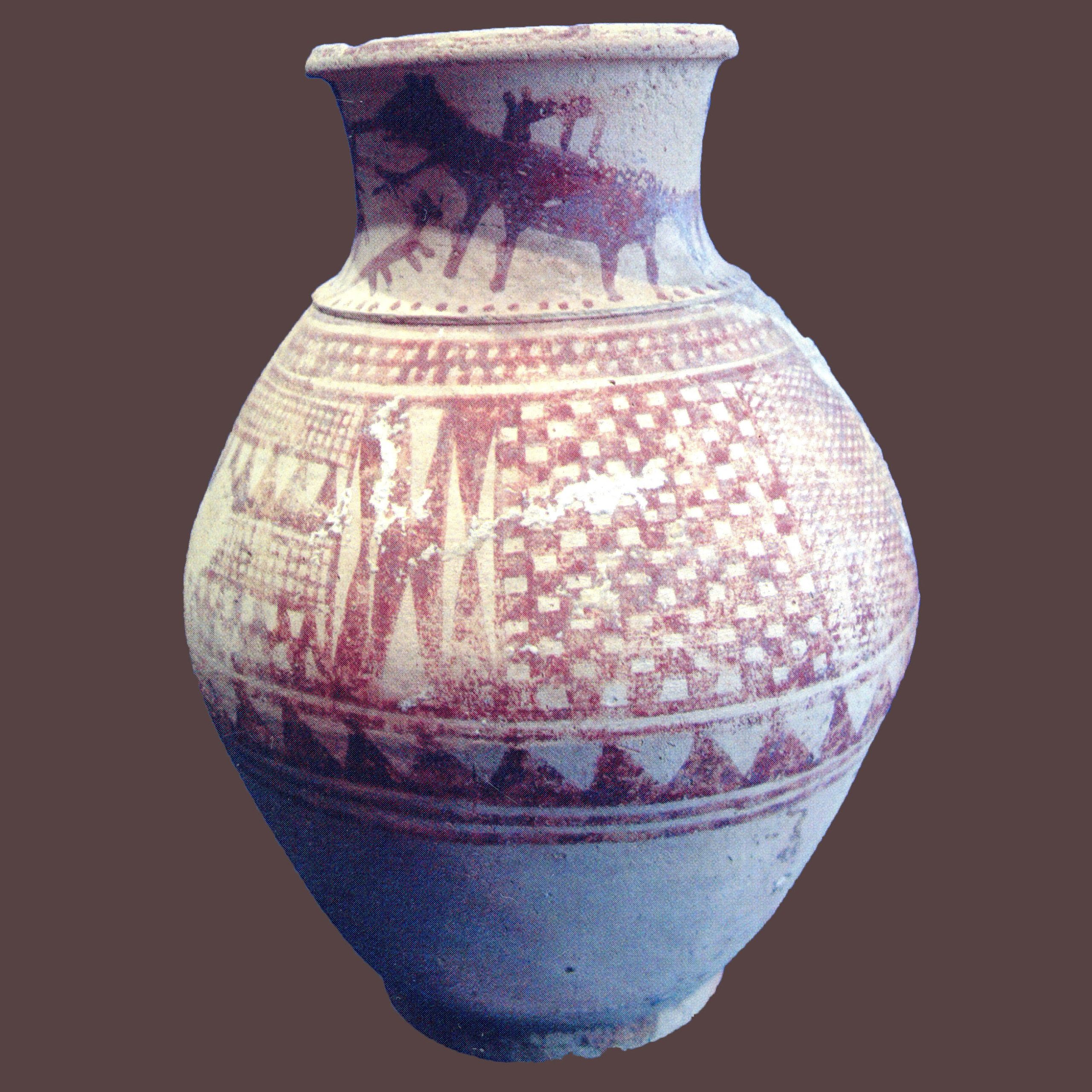

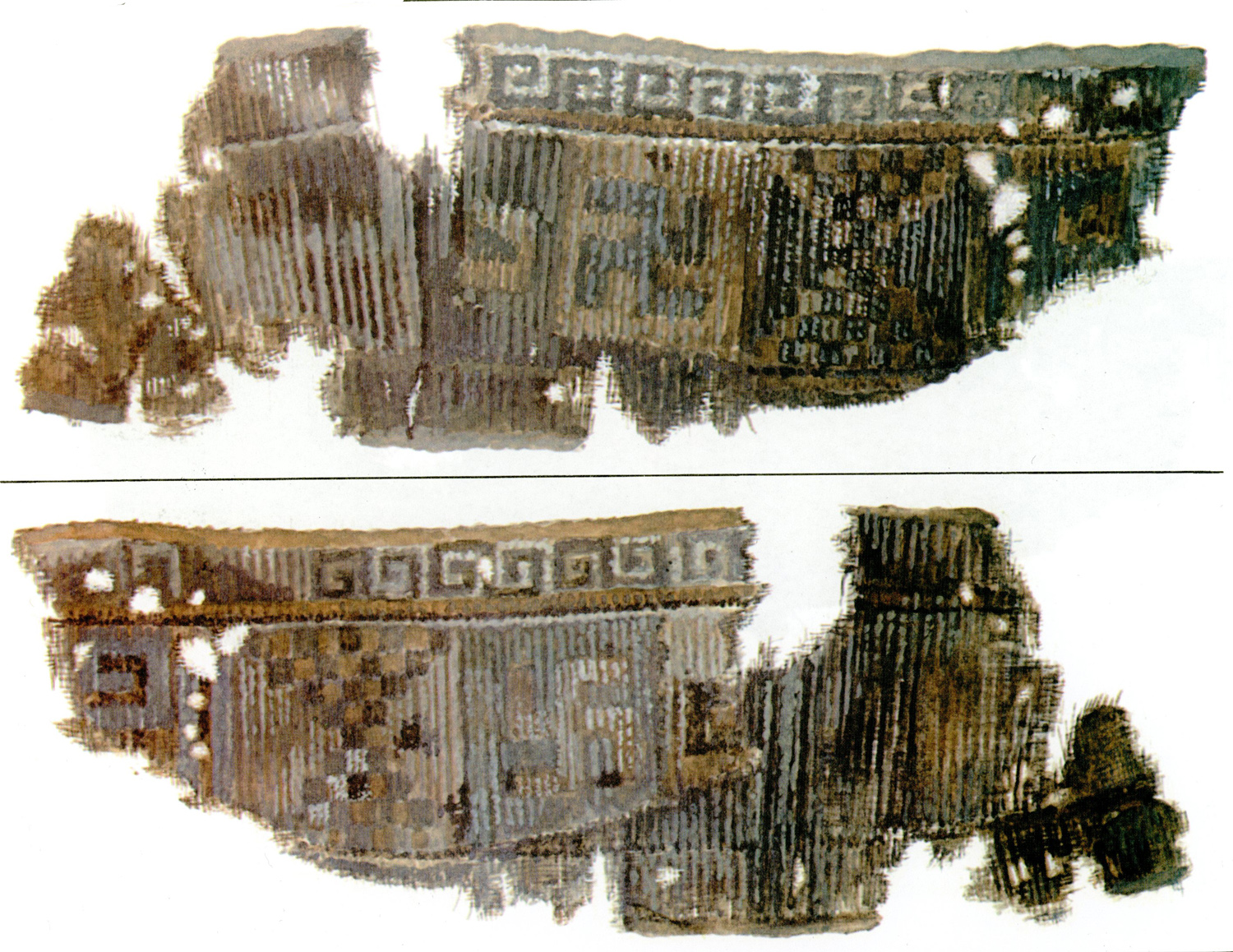

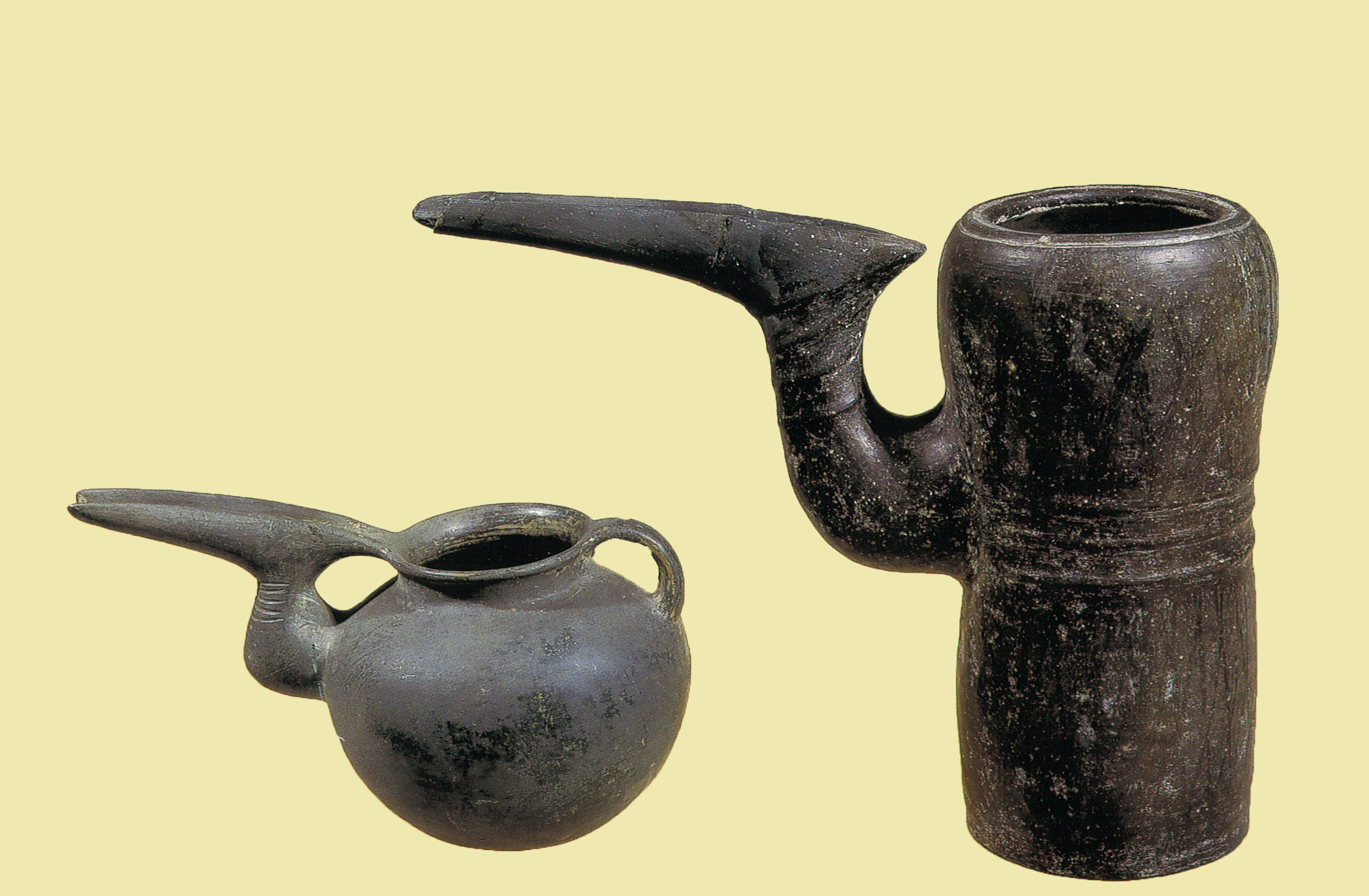

The remains of Period G found in Pits III and IV are dated to the second half of the third millennium B.C. based on the comparison with the ceramics of Susa II and Tepe Giyan IV. This period with the following Period D is marked by a thin, grit-tempered buff or orange ware decorated with geometric or bird motifs in black.

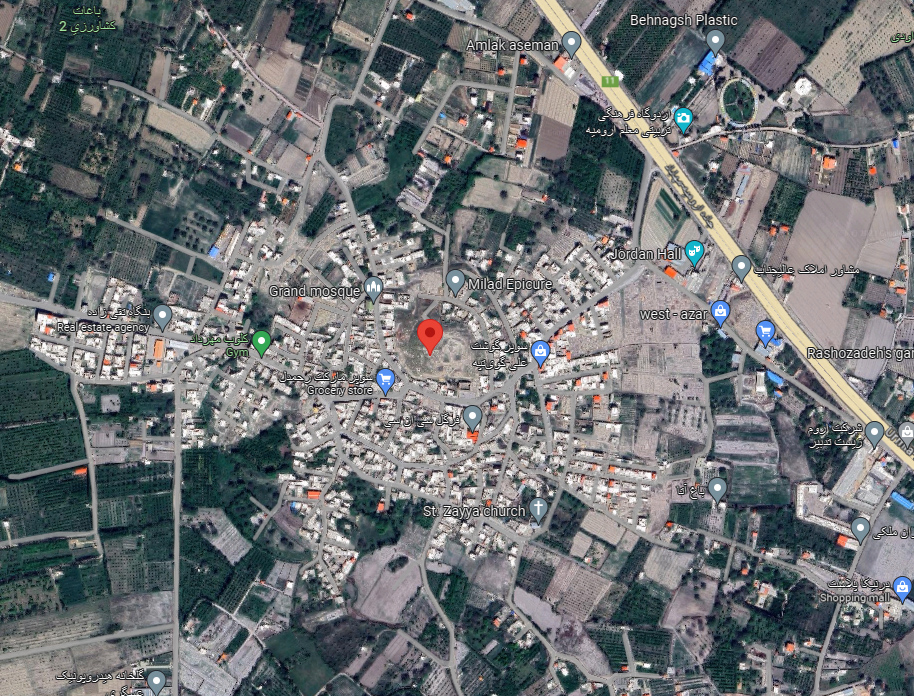

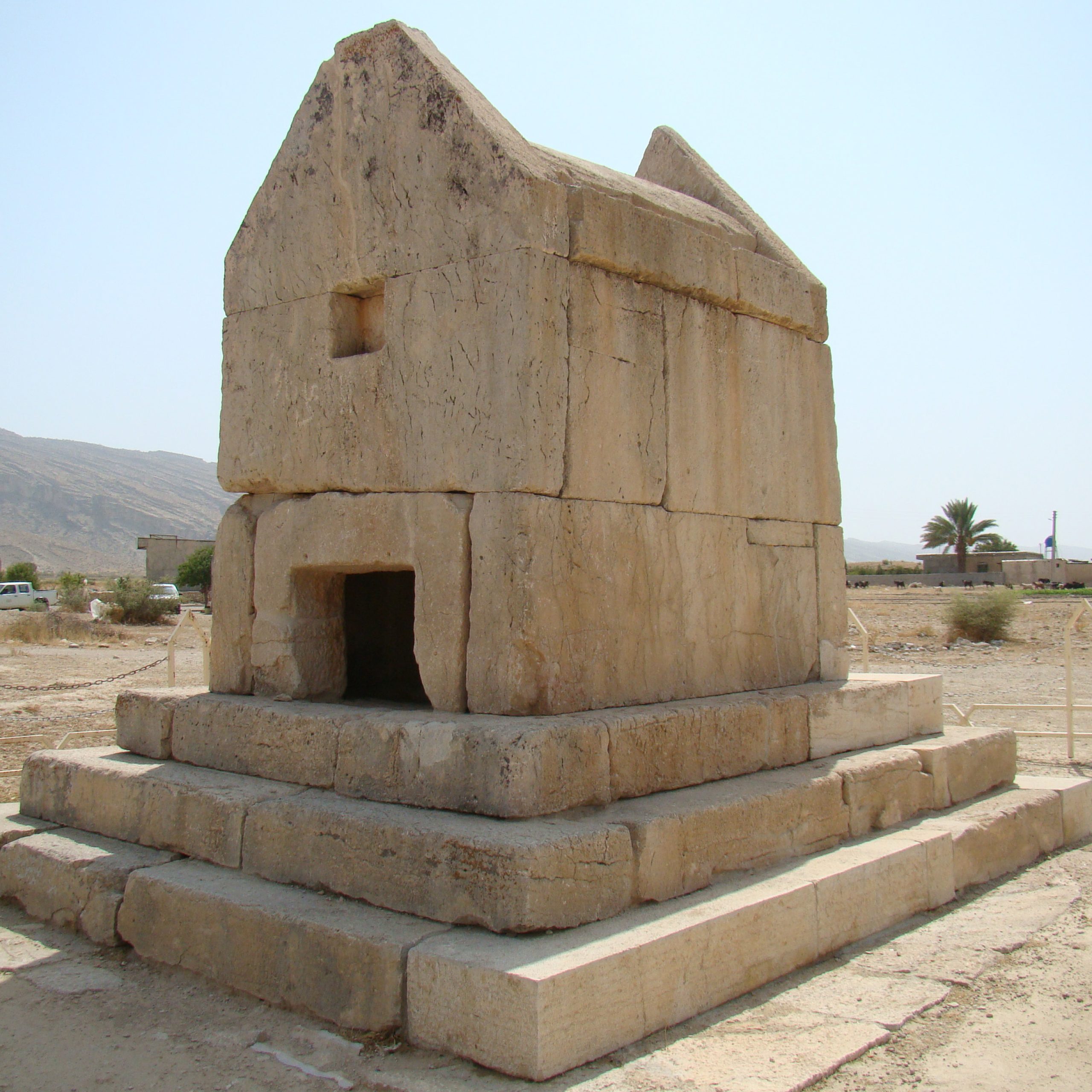

Burton-Brown’s Periods D and C fall in time of the spread of what is known as Urmia Ware associated with Haftvan VIIB in the first half of the second millennium B.C. In Period D, Geoy Tepe was rebuilt and there was a sizeable mud-brick wall on stone foundations, the materials of which “might have brought from the low hills a mile or two away to the west.” According to the excavator, the big wall was “much thicker than a house wall would be likely to be…This coupled with the fact that it followed a line which would easily have been taken by a defensive wall encircling the top of the Tepe, suggests that it was part of the fortifications of the city” (Burton-Brown, Excavations in Azarabijan, 1948, p. 70). Such a wall is visible in Erich Schmidt’s aerial photograph of Geoy Tepe (Schmidt, Flights, pl. 83). There are also characteristic potsherds known as the Khabur Ware found at other sites of the region such as Dinkhah Tepe and Hasanlu VI (Excavations in Azarabijan, 1948, pl. IX/24 and X/56). According to Robert Henrickson, this is an “intrusive phenomenon unrelated to the Painted Orange Ware of Hasanlu VII. Burton-Brown himself detected such a phenomenon when he wrote: “The change in pottery which occurred at the time of the beginning of the D period is so great that the only likely explanation is that new peoples then arrived at Geoy Tepe” (Excavations in Azarabijan, 1948, p. 69). Besides, Period D yielded several tombs. Four stone-built tombs (Tombs A, B, H, and J) and eight simple internments (Graves N, M, L. D, E, F, and G) were uncovered in Pit III. The excavator dates the stone-built tombs, found below the layer that contained simple burials, to Period D. It is quite possible that the graveyard was used over a long period of time ranging from Period D to Periods B and A.

Pits I, II, and IV contain Period B remains dating to the middle of the second millennium B.C.E. Pits I, II, and IV also contain Period A remains, mostly potsherds. It seems that the remains of Period A were larger in size, spreading over the entire mound in the late second millennium B.C.

Archaeological Exploration

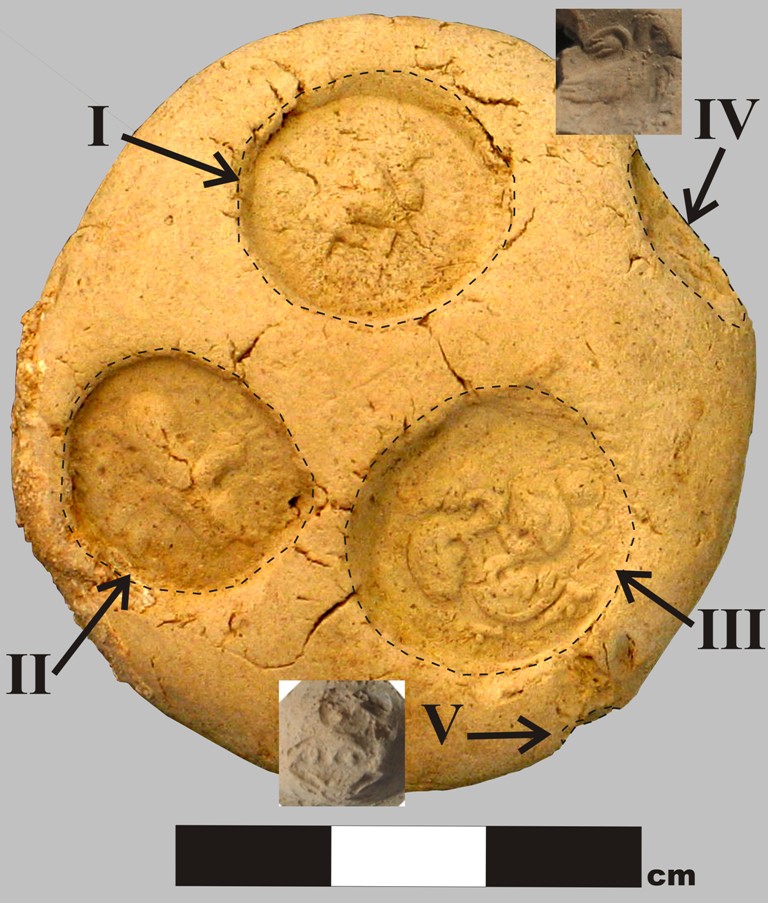

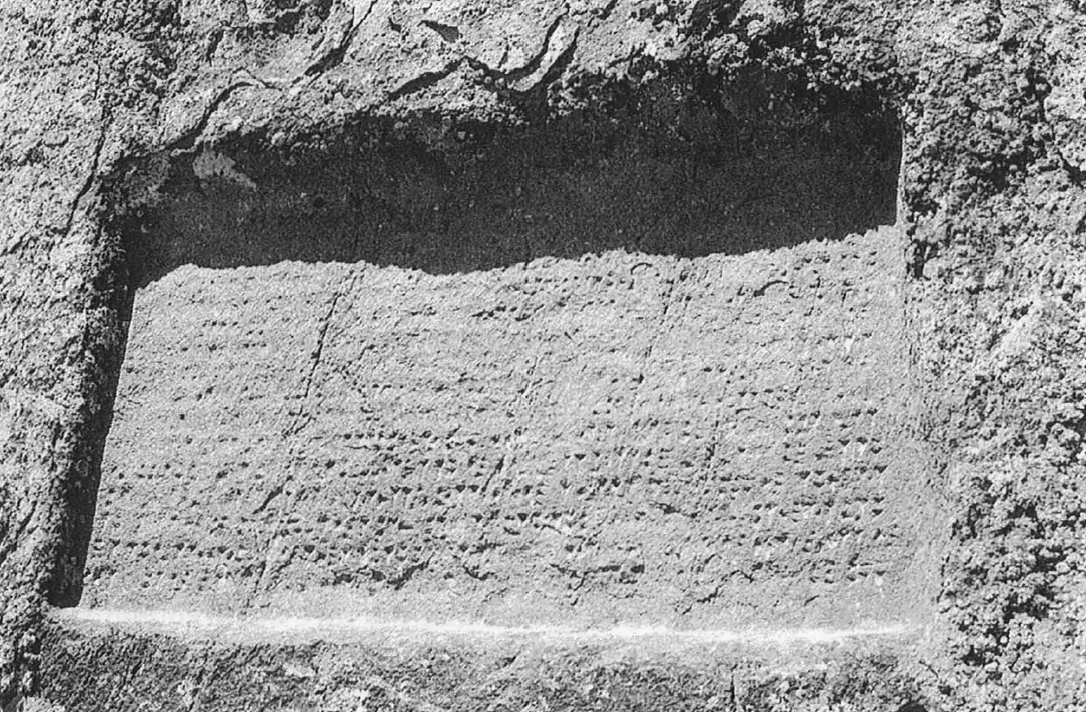

Carl Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt visited the area in the September of 1898 and excavated at Geoy Tepe which he refers to as Gok-Tapa. His interest in the site was first aroused by seeing a collection of objects excavated at Geoy Tepe in the “small museum” of the American Presbyterian Missionary in Urmia. They were presented to Lehmann-Haupt by two American missionaries named William Ambrose Shedd and Benjamin Woods. The objects were later acquired by the Ziegler Company in Tabriz and ended up in the hands of Dr. Rudolf Virchows (Lehmann-Haupt, Armenien einst und jetzt, p. 273). Then, he identified the mound as being the findspot of an Old Babylonian cylinder seal now in the Metropolitan Museum. Lehmann-Haupt describes Geoy Tepe as “an artificial elevation, a burial mound with stone-built tombs of various periods” (Armenien einst und jetzt, p. 276):

Der Hügel Gök-täpä, unser bald erreichtes Ziel, 7-8 km süd- lich von Urmia gelegen, ist im wesentlichen eine künstliche Erhebung, ein im Laufe der Jahrtausende entstandener Gräberberg. Den Kern und den Hauptbestandteil bilden Steinkistengräber verschiedener Perioden, die mit Erde überdeckt wurden. Selbst am Rande des Hügels lagen in dessen tieferen Schichten zahlreiche solcher Stein- kistengräber zutage.

By the time of Lehmann-Haupt’s visit, the Armenian village and church had covered most of the mound’s surface and there was a church built by the Presbyterian mission, “mostly made of massive ashlars and stone slabs taken from the graves, as well as the surrounding wall, which partly extends into the plain” (Armenien einst und jetzt, p. 273). He thought that Geoy Tepe was a burial ground with cist tombs of various periods. He excavated several tombs containing grave goods rich in precious metals, beads, and pottery vessels. He concluded that the whole site was the necropolis of Lullubi princes around 2000 B.C. (Armenien einst und jetzt, p. 279):

Einen vor oder um 2000 v. Chr. lebenden Fursten der Gutiaer oder Lulubaer Zylinders vorzustellen haben, den man ihm in sein Grabgewolbe in der untersten Schicht der Nekropole von Gok-tapa mitgegeben hat.

In 1903, Frank Russel Earp, then a fellow of the King’s College at Cambridge, England, dug up four stone-built tombs on “Gok Tapa.” The report of his work was later published by Harriet Crawford (see the bibliography). In 1936, Sir Aurel Stein collected potsherds of grey-black burnished pottery but did not mention Earp’s work, most likely because no traces were left at the time of his visit. Finally, Theodore Burton-Brown carried out an excavation season in the summer of 1948, with funds gleaned from various British institutions, including the Leverhulme Trustees, the British School of Archaeology in Baghdad, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The mound was explored with limited means and no research design. The excavated areas were not connected but consisted of eight scattered pits or trenches.

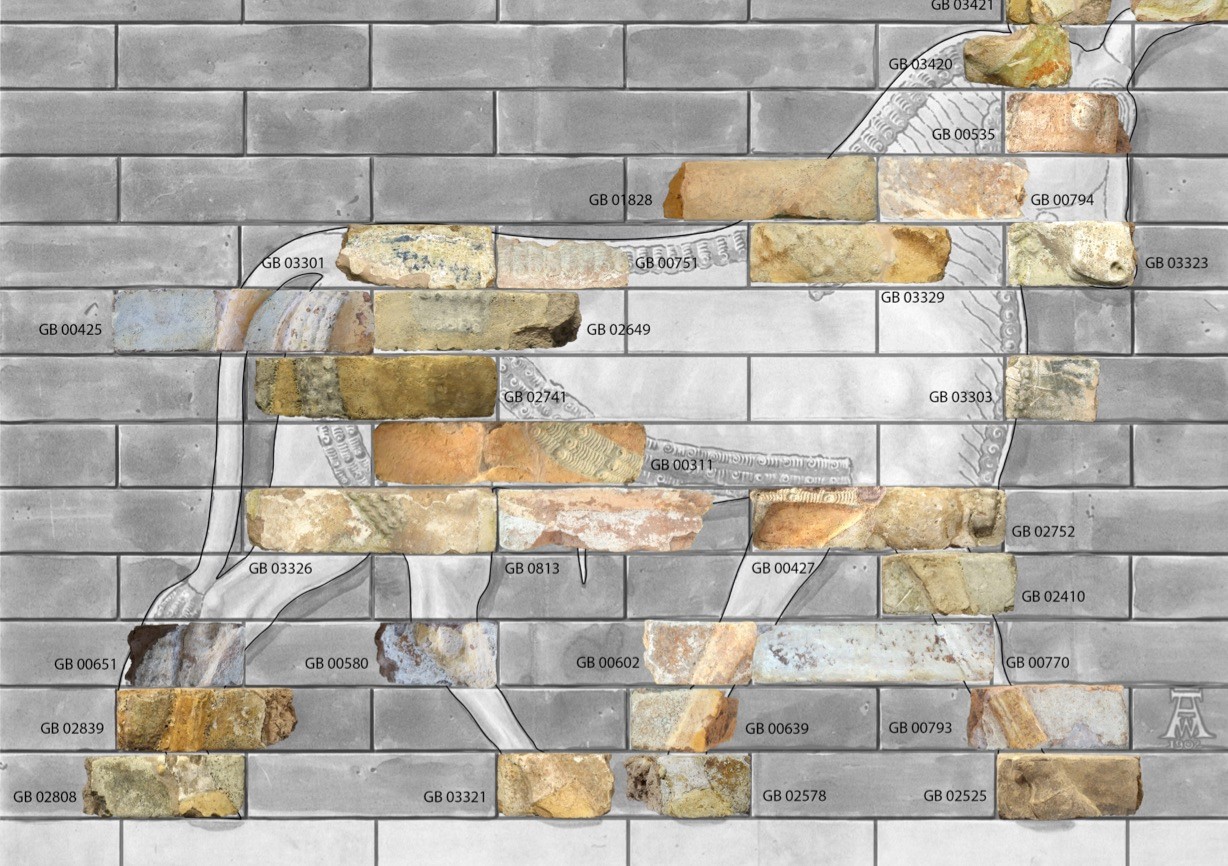

The excavated finds consist of painted and plain pottery, bronze and iron objects, beads, cylinder seals, and skeletal remains. A collection of the finds are now in the British Museum:

Bibliography

Burton‐Brown, T., “Azerbaijan, ancient and modern,” Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society, vol. 36/2, pp. 168-177.

Burton-Brown, T., Excavations in Azarbaijan, 1948, London, 1951.

Crawford, H., “Geoy Tepe 1903. Material in the Collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 11, 1975, pp. 1-28.

Edwards, M., “ ‘Urmia Ware’ and Its Distribution in North-Western Iran in the Second Millennium B.C.: A Review of the Results of Excavations and Surveys,” Iran, vol. 24, 1986, pp. 57-59 (for Geoy Tepe).

Fleming, S. J., L. -A. Bedal, and C. P. Swann, “Glassmaking at Geoy Tepe (Azerbaijan) during the Early 2nd Millennium BC: A Study of Blue Colourants Using PIXE Spectrometry,” in Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology 1993, J. Wilcock and K. Lockyear (eds.), Oxford, 1994, pp. 199-204.

Henrickson, R., “Ceramics vii. The Bronze Age in Northwestern, Western, and Southwestern Persia,” Encylopedia Iranica Online, © Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. Consulted online on 12 May 2023 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_7642>

Lehmann-Haupt, C. F., Armenien einst und jetzt, vol. 1, Berlin, 1910 (pp. 276-277, 282-283, for Geoy Tepe).

Negahban, E. O., “Geoy Tepe,” Encyclopedia Iranica Online, © Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. Consulted online on 12 May 2023 http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_2057

Sagona, A. G., The Caucasian Region in the Early Bronze Age, Oxford, 1984, pp. 60-61 (for Geoy Tepe).