Firuzabad/Shahr-e Gūr/Ardashir Khwarrahفیروزاباد/شهرگور/اردشیر خوره

Location: Firuzabad is in the vicinity of a town of the name in southern Iran, Fars Province.

28°50’60.0″N 52°31’54.5″E

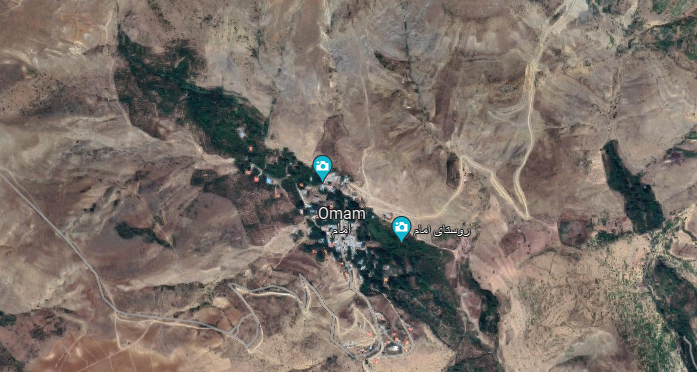

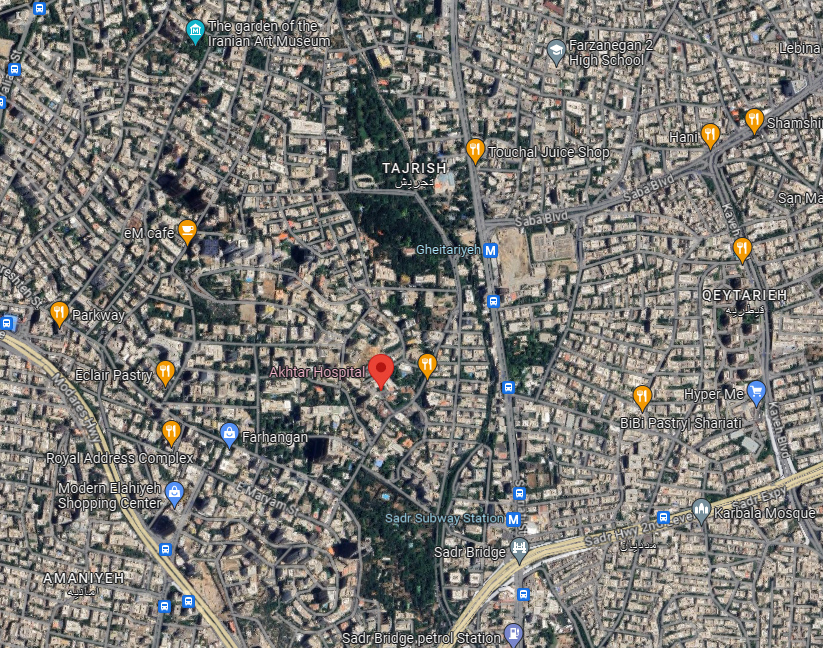

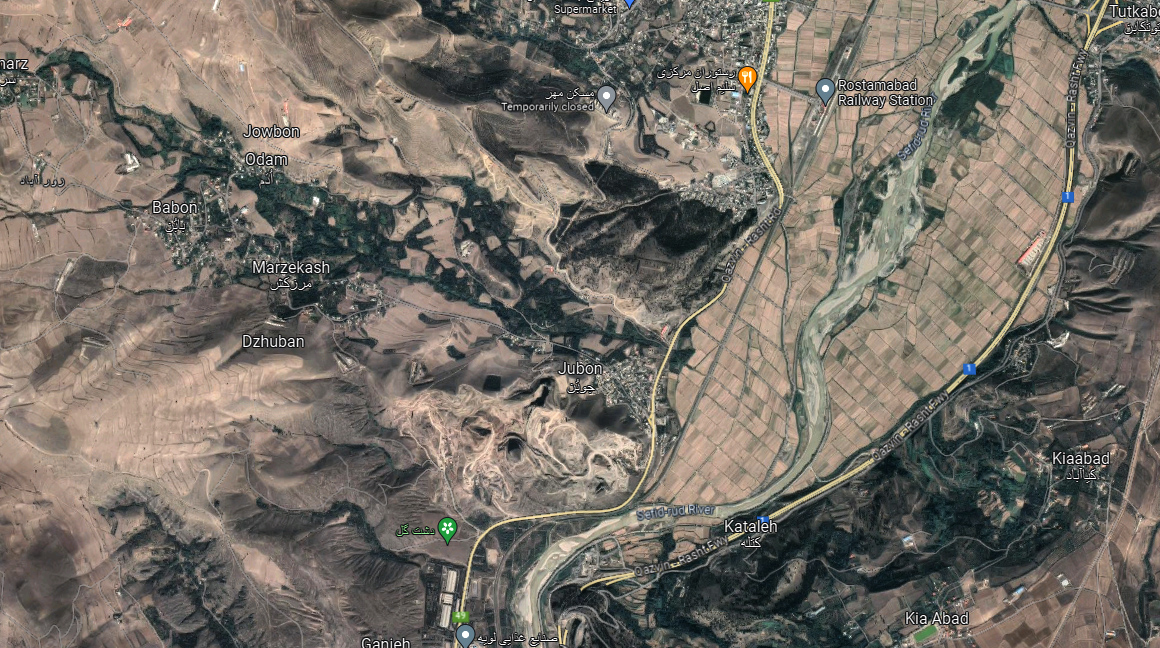

Map

Historical Period

Sasanian, Islamic

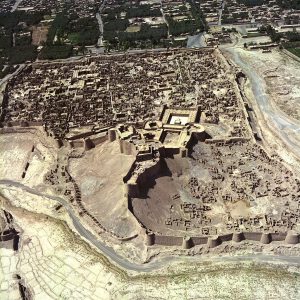

The most significant Sassanian archaeological site in the Firuzabad Plain is the city of Ardashir Ardashir Khwarrah (The Glory of Ardashir). Concerning the city’s foundation date, it seems that the archaeological remains provide compelling evidence – and confirm Ṭabarī’s account – for the construction of the city before Ardashir’s decisive victory over Ardavan’s army in A.D. 224. According to the Middle Persian prose tale known as Karnamag Ardashir Papakan (Book of the Deeds of Ardashir), the site of Ardashir Khwarrah in the Firuzabad Plain was a marshland. Ardashir ordered it to be meticulously drained to prepare the terrain for the city’s construction. The Karnamag, a literary account mixed with legends, provides a concise and seemingly plausible account of Ardashir’s undertakings at Firuzabad. These include the creation of irrigation canals and the excavation of a water tunnel through a mountain. This transformation included the implementation of a land allotment system and the transfer of water from the Tang Ab River, facilitating the development of farming activities across the plain. The Sasanian vestiges are concentrated in the central area while most of the city’s urban sectors remain unexplored and are now under cultivation by farmers of the nearby villages. Amidst the remains of the ancient city, there are imamzadehs or shrines of the Islamic period near the city’s central area. These shrines are characterized by their square rooms constructed using stones taken from the nearby Sasanian ruins.

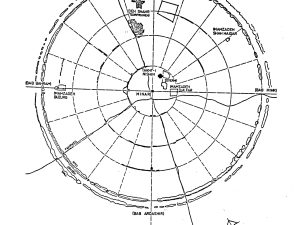

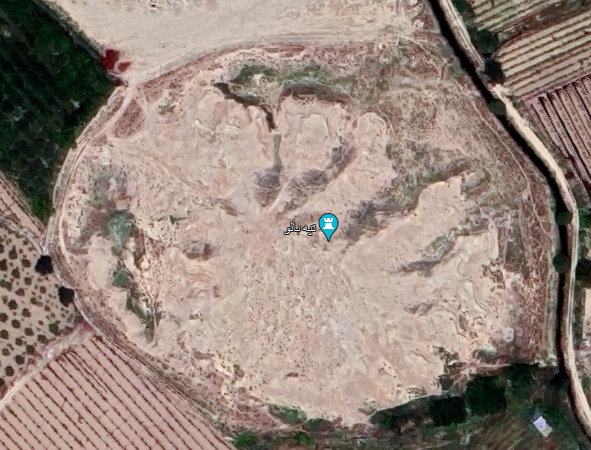

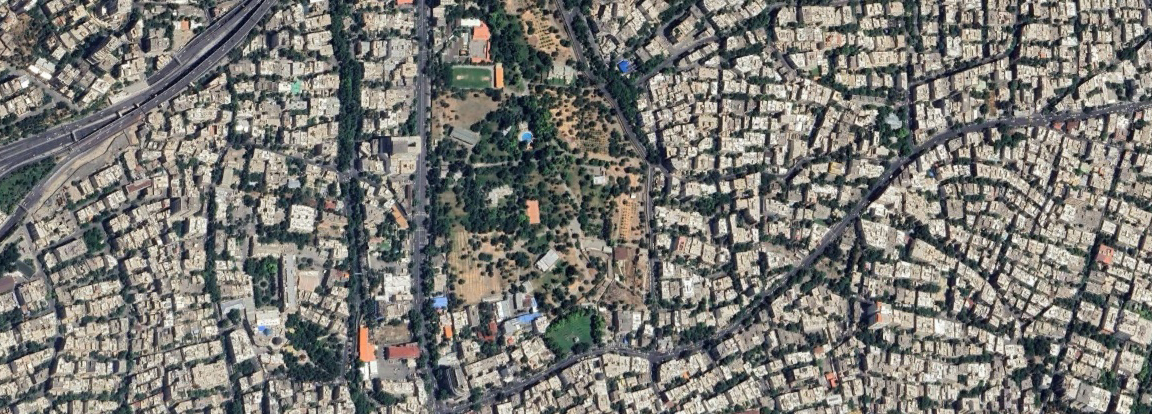

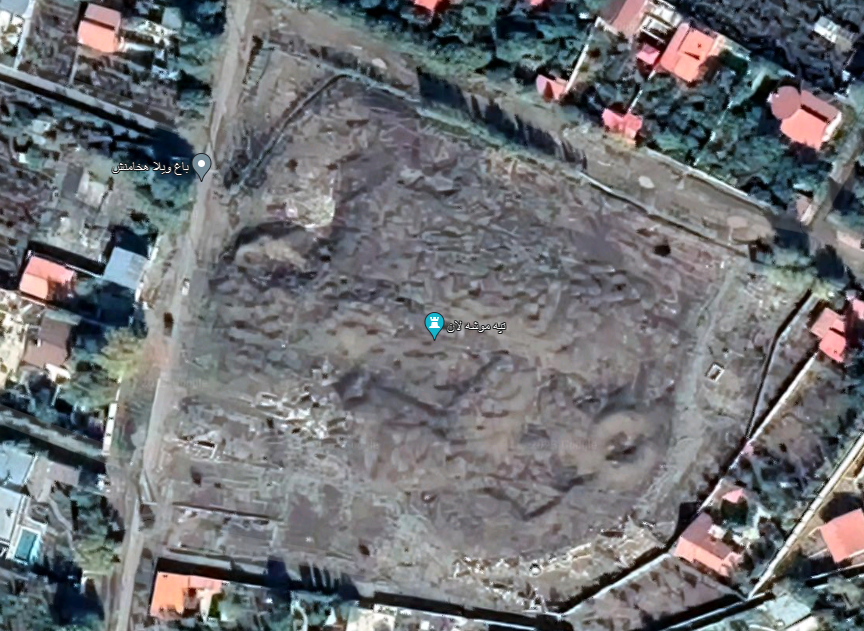

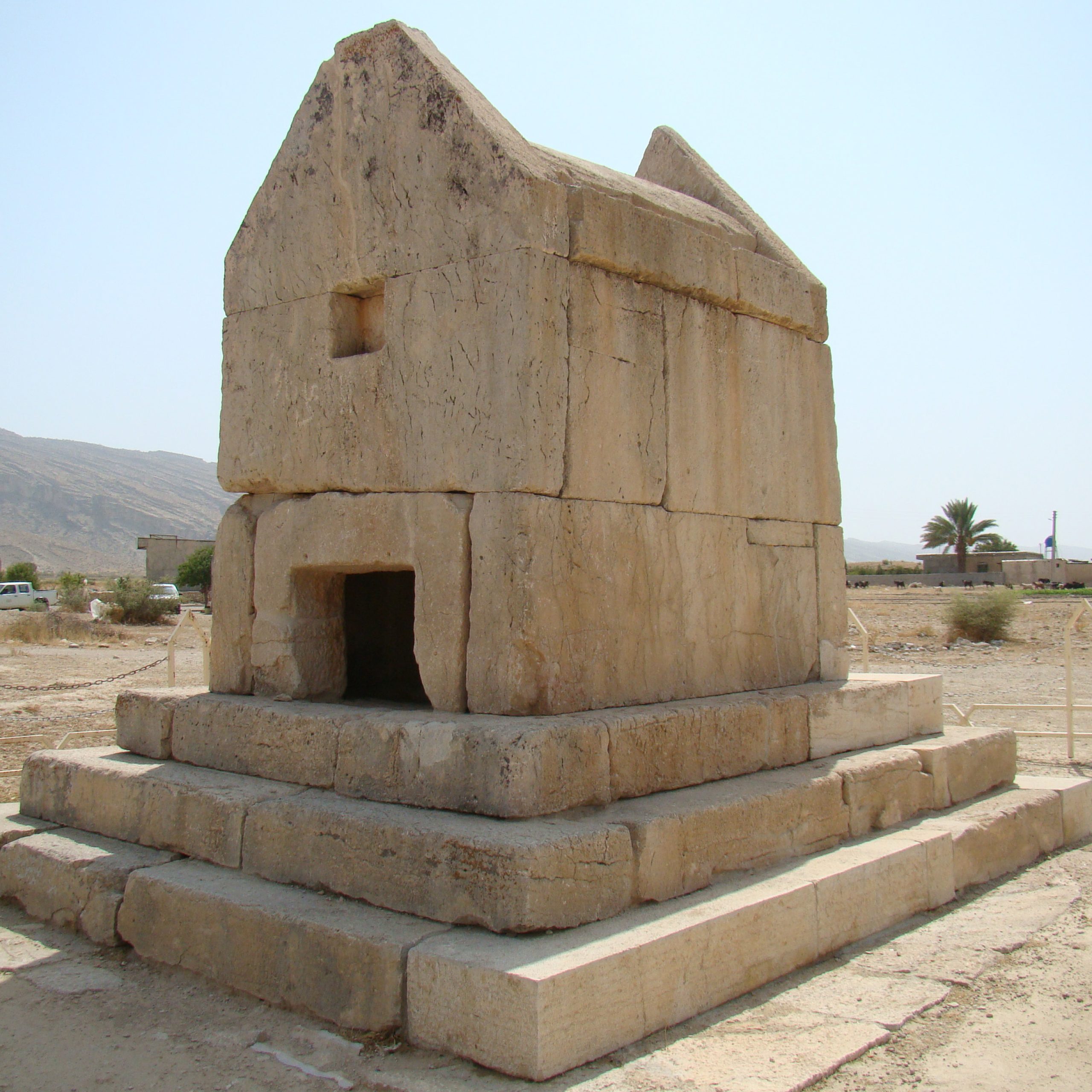

The city’s layout adhered to a perfect circular design, with a diameter of 1950 meters (fig. 1). It was organized into twenty sectors or slices through a precise geometric system, featuring twenty radial and numerous concentric streets (fig. 2). A fortified wall encircles the city and consists of an inner mud-brick wall, a 35-meter-wide moat, and an outer defensive wall. The city has four gates built in the inner wall, the remains of which can still be seen today. A network of circular and concentric streets with residential and commercial neighborhoods encircles the central part which is 400 m in diameter. This area was enclosed by fortifications and featured an impressive quadrangular tower known as Tirbal measuring 20 meters in width and 40 meters in height, positioned at the city’s center (fig. 3). The tower-like Tirbal stands at the very center of the city. The tower, built in rubble masonry, was a stair-tower. Considering the width of the ruined stairs and the outer walls, it appears to have measured approximately 20 meters on each side. The tower served the dual purpose of maintaining visual contact with the fortifications such as those at Qal’eh Dokhtar. Besides, it also played a crucial role in topographic surveying activities during the initial construction phases of the town. The remains of Takht Neshin actually consist of a cubic stone structure with four rooms or eyvans extending from each of its sides. The central room was once capped with a 14-meter-wide dome. Takht Neshin is likely to have functioned as Ardashir’s fire temple, as described in the Karnamag and other historical accounts. Nearby, there are some small Achaemenid-style column shafts. However, these columns, often taken as evidence for dating the building to the Achaemenid period, vary in design and were likely repurposed for a different use after being brought to the site.

Outside the city wall, there are traces of canals, walls, and ruined structures, which continue up to 10 km in distance from the city’s center. Some 10 km southeast of the city’s center there are ruins of a fort with a round moat with Sasanian potsherds. Traces of a garden designed with a circular pool and a building are located 4.5 km northwest of the city while an arrangement of walls on a plateau 6 km to the northeast indicates the existence of a graveyard. Approximately 10 kilometers to the southwest, near the river's exit from the plain, you can find the vestiges of water channels and a solitary arched aqueduct. Finally, in a dry, adjacent valley located beyond a mountain ridge, a wall, which is likely to be part of an aqueduct, runs precisely in a north-south direction. This aqueduct was supplied with water from springs in the eastern Firuzabad plain through a stone channel, which crossed the ridge via a tunnel carved into the rock. All this corroborates with historical medieval accounts such as those by Ibn Hawqal and Ibn Balkhi about Ardashir’s endeavor to cut through a mountain in order to drain the plain.

The Palace of Ardashir:

The partly ruined Palace of Ardashir, which was erroneously called Atashkadeh by the local people and earlier publications, lies 2 km north of the city. The absence of any fortified wall suggests that the monument was built when Ardashir had established his supremacy as the new king probably after 224 or 225 A.D. The whole site of the palace, including the pond in front of it, covers an area of 8500 m². The palace was built in rubble masonry and gypsum mortar and was once covered with plaster. The entire building measures 108 x 55 m. The main entrance in the form of an eyvan is 22 m high and 14 m wide. The interior consists of a long vaulted hallway leading to three 14 x 14 m rooms within the palace. The square halls are domed using an innovative technique known as squinches, transferring from a square plan to a circular one. In one of the domed halls, parts of the original plaster coating on the walls display stucco elements reminiscent of Achaemenid architectural influences. Beyond the domed halls, there is an open courtyard with side rooms, measuring 20 x 20 m with two eyvans situated on the long axis.

Archaeological Exploration

Medieval Iranian historians describe the Sasanian remains at Firuzabad as early as the 10th century, though it is uncertain whether they had first-hand knowledge of the ruins or relied on earlier sources for their accounts. Istakhri provides the earliest known description of the site in his Masalik va Mamalik, a 10th-century book, while the most comprehensive account regarding the city’s construction and its remains comes from Ibn Balkhi, the author of a Fārsnāma, compiled during the Saljuq period, probably between 1104 and 1110 A.D. All these sources have been collected and put together by Paul Schwarz (see, Iran im Mittelalter, pp. 57-58). The road connecting Shiraz to Firuzabad takes a winding route and is therefore not frequented by travelers and caravans. As a result, the earliest recorded visits to the ruins date to the years 1840-41 when Eugène Flandin and Pascal Coste gave a detailed description of the ruins and took Takht Neshin as the foundation of a tomb much the same as the Tomb of Cyrus at Pasargadae. In 1881, Marcel Dieulafoy traveled to Fars and visited the ruins. He later published his survey of the site’s major monuments, including the reconstructions of the watch-tower and Takht Neshin (Dieulafoy, L’art antique de la Perse). His wife, Jane Dieulafoy, published an account of their visit to the area and the ruins (Dieulafoy, La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane). In the 20th century, the visit of Ernst Herzfeld to Firuzabad marked a turning point as he was the first archaeologist who rightly understood the form and function of Sasanian remains such as the Tirbal (Herzfeld, “Reisebericht”). He also published a thorough study of the rock reliefs along the Tangāb River (Herzfeld, “La sculpture rupestre de la Perse sassanide”). In 1933-34, Sir Aurel Stein visited Firuzabad and published a detailed description of all archaeological remains, including those of Shahr-e Gūr (Stein, “An Archaeological Tour in Ancient Persis”). In 1947, Roman Ghirshman published a comprehensive critique of prior research, wherein he proposed a new perspective on the Tirbal, suggesting that it might have served as a tower with a burning fire atop (Ghirshman, “Firouzabad”). The archaeological fieldwork began in 1968 when Dietrich Huff embarked on a new set of investigations at Qal’eh Dokhtar and Shahr-e Gūr, to prepare the site for a comprehensive archaeological exploration of the site on behalf of the German Archaeological Institute. The comprehensive archaeological project at Firuzabad was interrupted in 1979. In 2005 the Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran undertook brief excavations at Firuzabad to explore the area within the city’s circular enclosure. Three areas were selected for fieldwork: the area of the high tower (terbal), the Takht Neshin or fire temple ( chāhārtāq ), and the palace. Research at the foot of the terbal revealed traces of steps belonging to a staircase that once led to the tower's upper levels. The excavation in the northern sector of the central area in the winter of 2006 brought to light a series of wall and floor paintings depicting royal figures. Paintings, apparently found on coffins in a subterranean tomb near show the busts of two young women, a young man, and a boy. The style and treatment of these paintings reflect the influence of Parthian art still in force in the early years of the Sasanian Empire. It has been suggested that the figures are Sasanian princes or dignitaries. The archaeological remains located between Qal’eh Dokhtar and Shahr-e Gūr were inscribed on the World Heritage of UNESCO in 2018.

Bibliography

Dieulafoy, J., La Perse, la Chaldée et la Susiane, Paris, 1887, pp. 480-487 (for Firuzabad).

Dieulafoy, M., L’art antique de la Perse, Paris, 1884-1889, vol. IV, pp. 30-71, pls. XII-XVII (for Firuzabad).

Ibn al-Balkhi, Description of the Province of Fars at the Beginning of the Fourteenth Century. From the MS of Ibn al-Balkhi in the British Museum, translated by G. Le Strange, London, 1912, pp. 44-45 (for Firuzabad).

Ibn al-Balkhi, The Fārsnāma of Ibnu’l-Balkhi, edited by G. Le Strange and R. A. Nicholson, London, 1921, pp. 137-138 (for Firuzābād).

Flandin, E., Voyage en Perse, vol. 2, Paris, 1851, pp. 339-344.

Flandin, E., and P. Coste, Voyage en Perse, Paris, 1834-54, vol. I, pls. 34-44; vol. V (text), pp. 36-45.

Ghirshman, R., “Firouzabad,” Bulletin de l’institut français d’archéologie orientale du Caire, vol. 46, 1947, pp. 1-28.

Herzfeld, E., “Reisebericht,” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, N.S., vol. 5, 1926, pp. 252-256 (for Firuzābād).

Huff, D., “Zur Rekonstruktion des Turmes von Firuzabad,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen, vol. 19/20, 1969/70, pp. 319-338.

Huff, D., “Der Takht-i Nishin in Firuzabad,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 1972, pp. 517-540.

Huff, D., “An Archaeological Survey in the Area of Firūzābād, Fārs, in 1972,” Proceedings of the IInd Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, Tehran, 29th October-1st November 1973, edited by F. Bagherzadeh, Tehran, 1974, pp. 155-179.

Huff, D., “Fīrūzābād,” Shahrhā-ye Iran, edited by M. Y. Kiani, vol. II, Tehran, 1366/1987, pp. 75-117. In Persian

Huff, D., “Architecture sassanide,” Splendeur des Sassanides, Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'Art et d'Historie, 12 Fevrier au 25 avril 1993, Brussels, 1993, pp. 45-61.

Ja’fari Zand, A., “Kashf-e ārāmgah-e manghūsh dar Shahr-e Gūr (Ardashir Khwarrah), Firuzabad.” In Firuzabad. History and Culture, edited by R. Karachi, Tehran, 2017, pp. 253-311. In Persian.

Stein, A., “An Archaeological Tour in the Ancient Persis,” Iraq 3, 1936, pp. 113-230.

Schwarz, P., Iran im Mittelalter, vol. II, Leipzig, 1910, pp. 56-58 (for Firuzabad).