Bāzeh-Hūrبازه هور

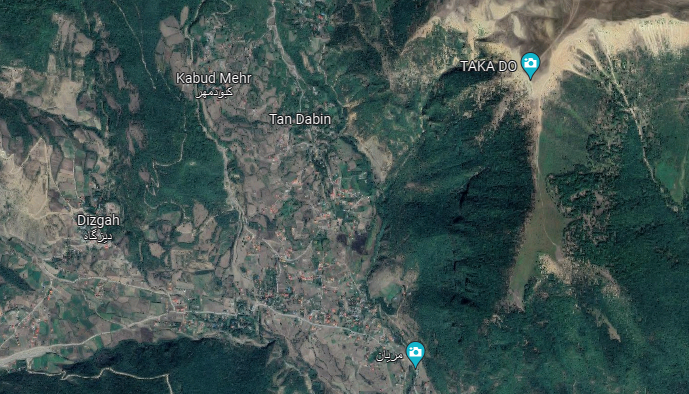

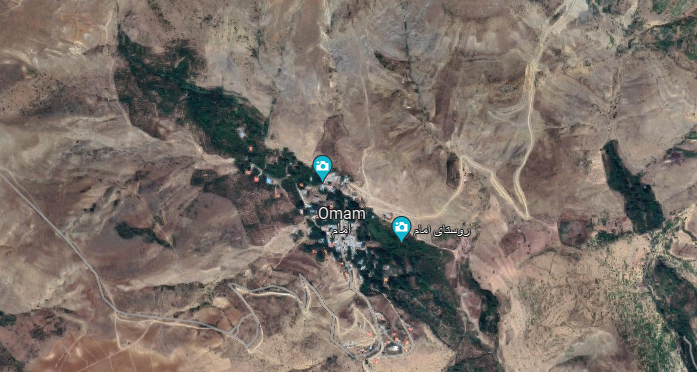

Location: The site of Bāzeh-Hūr lies 75 km southeast of Mashhad, northeastern Iran, Khorāsān-e Razavi Province.

35°46’3.03″N 59°22’42.35″E

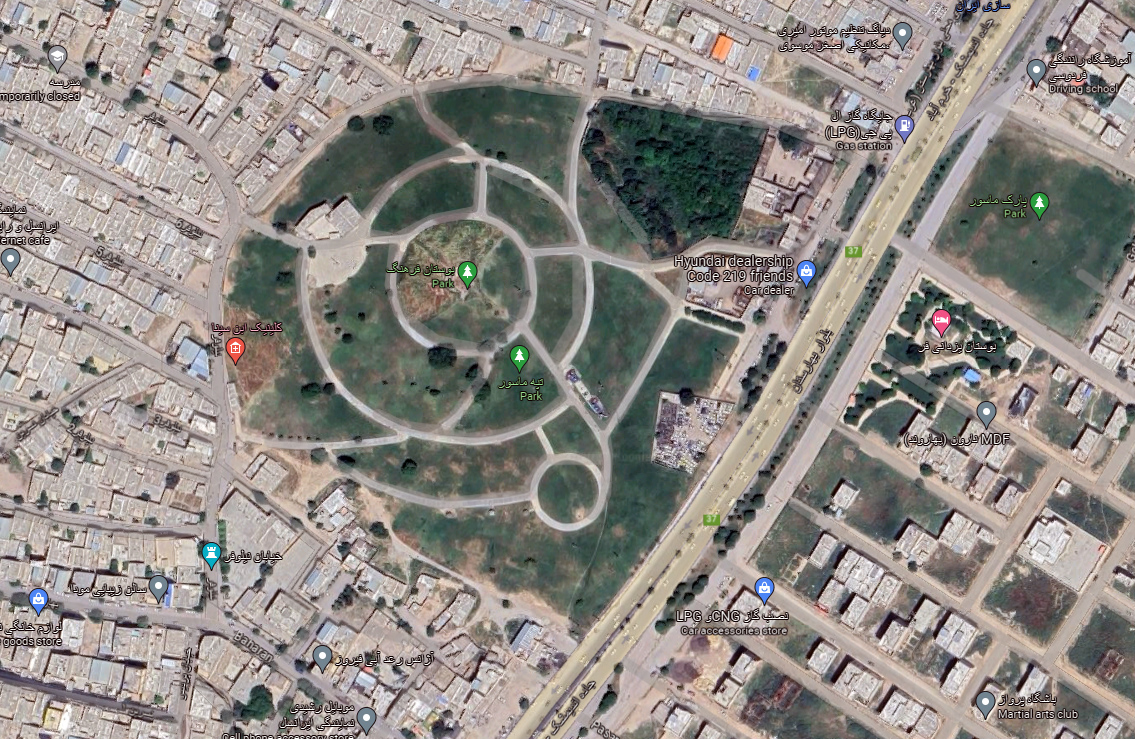

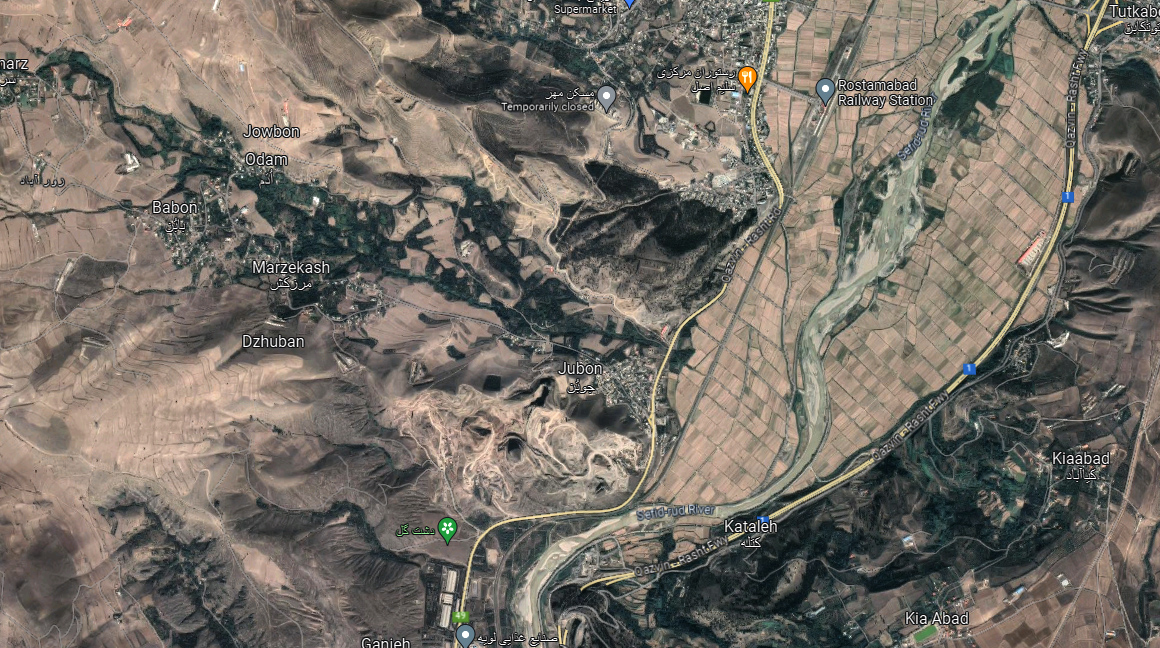

Map

Historical Period

Parthian/Sasanian/Islamic

History and description

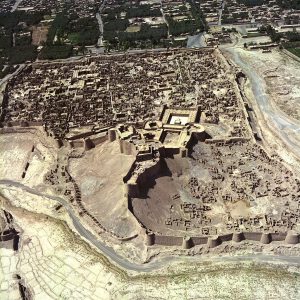

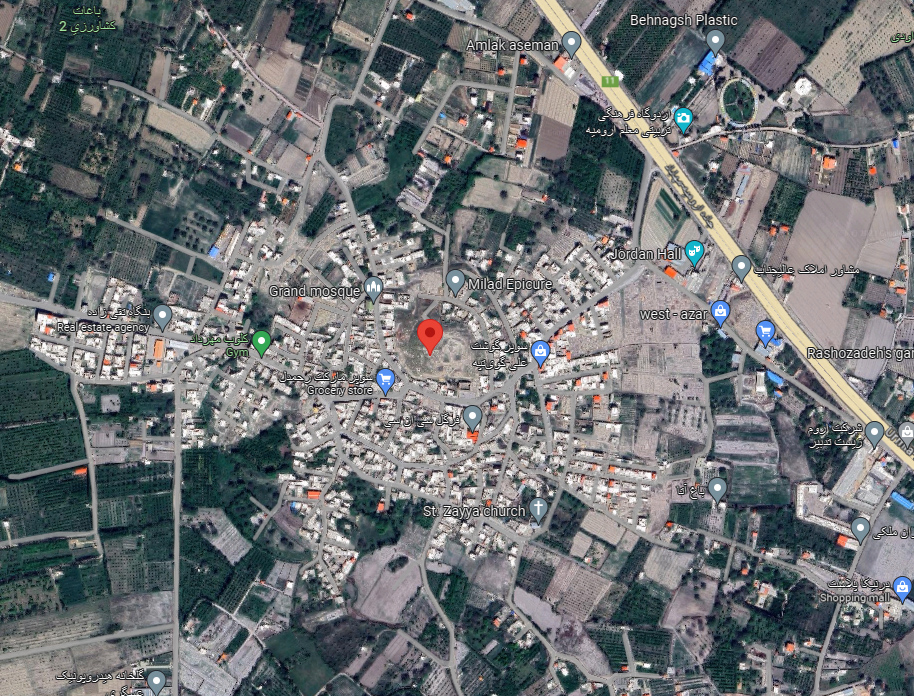

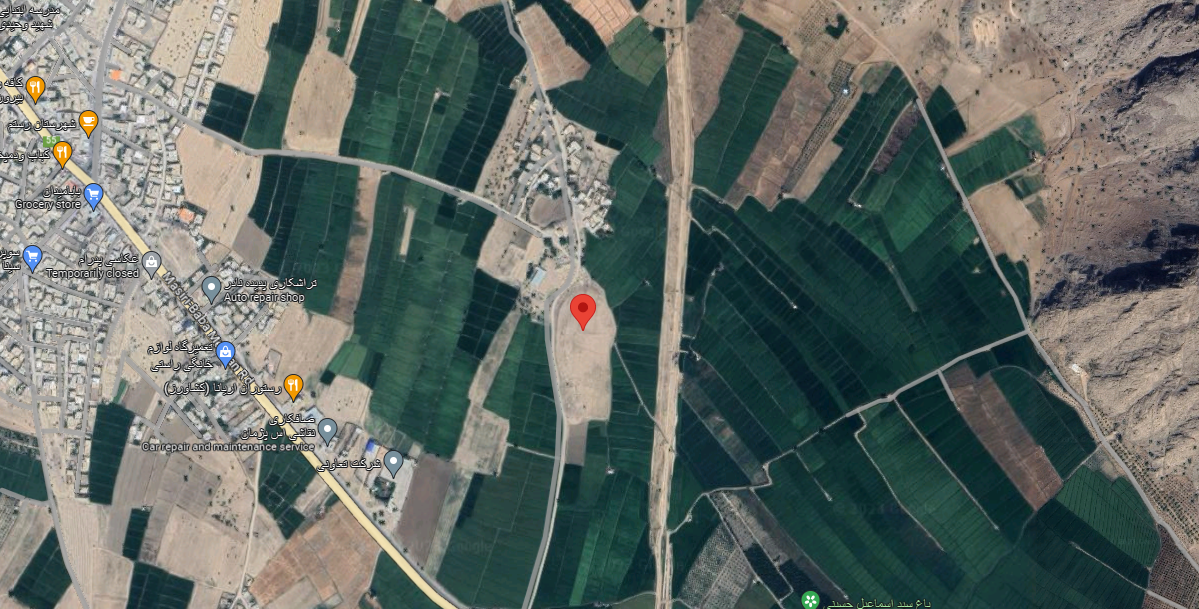

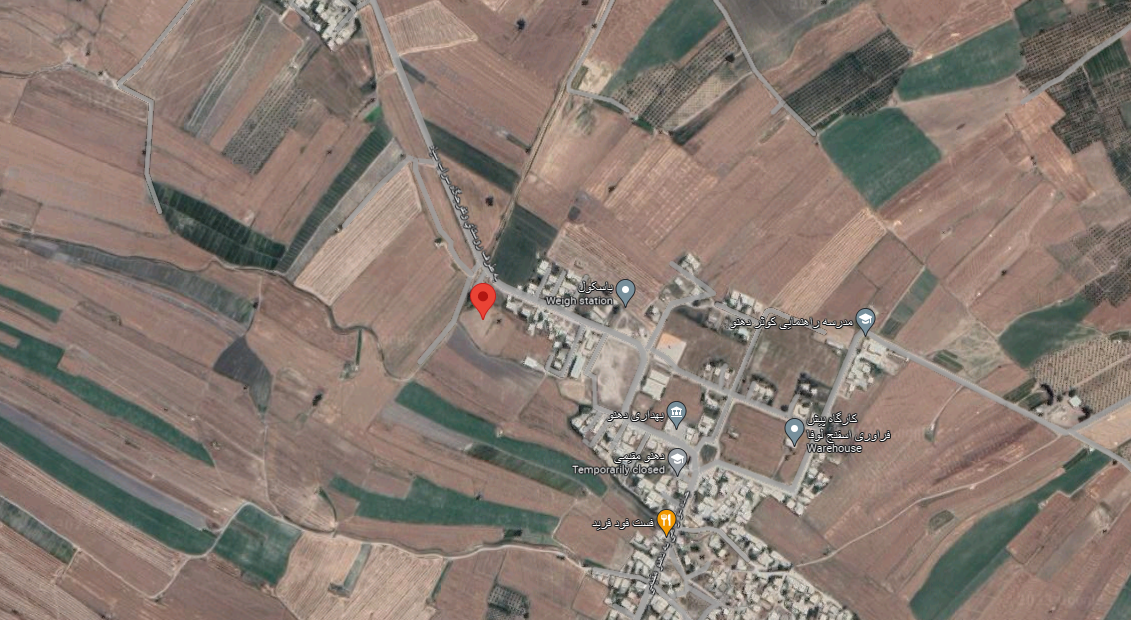

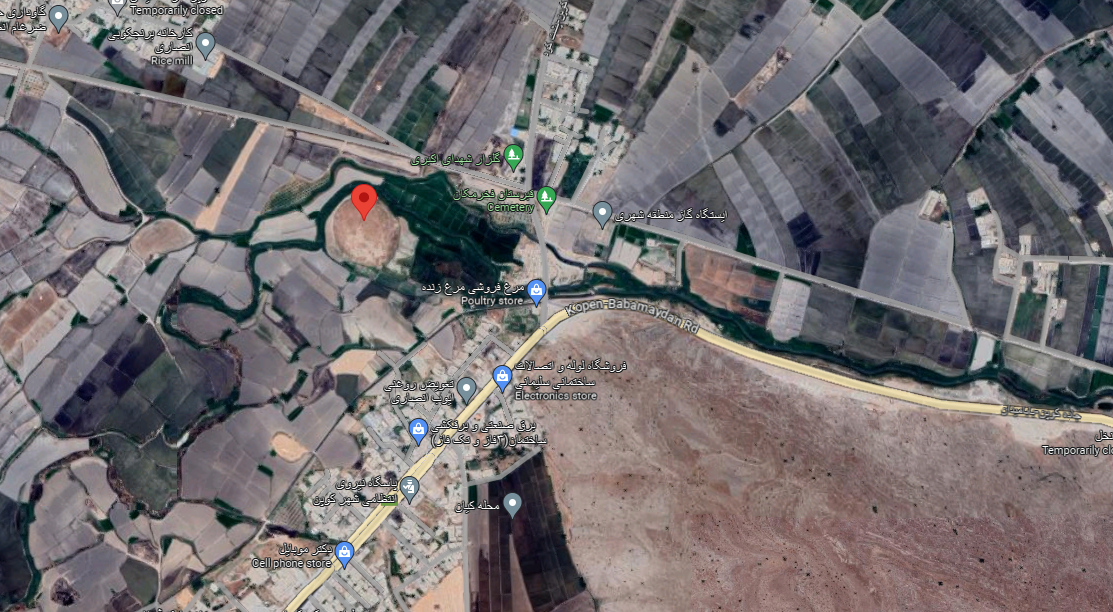

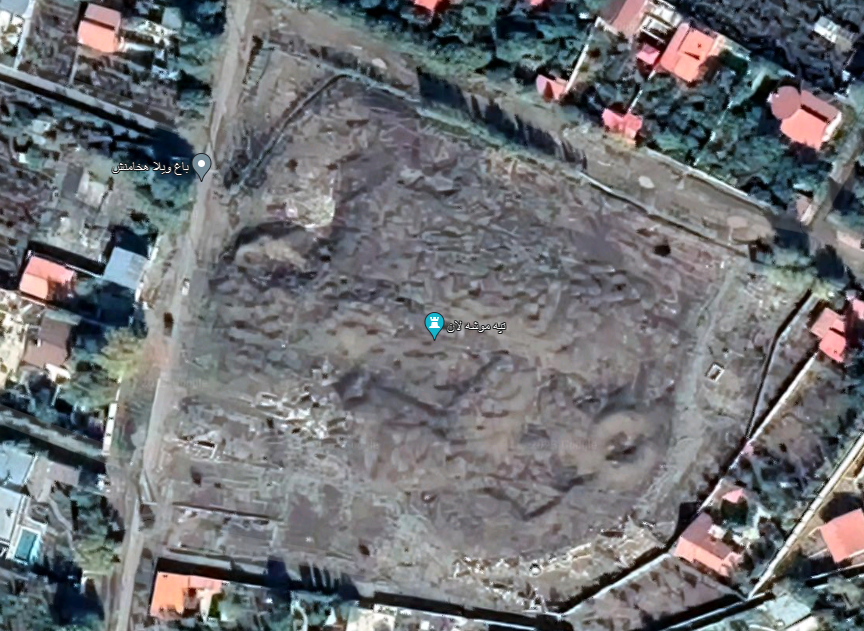

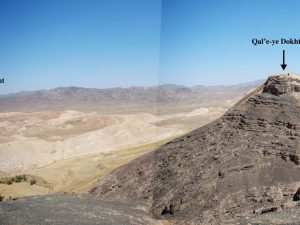

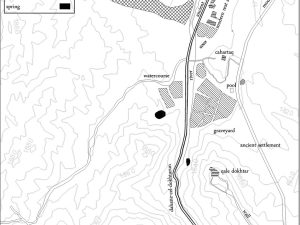

The site of Bāzeh-Hūr lies 3 km southeast of a village of the same name, and 1.5 km south of the Robāt-e Sefid village, 75 km southeast of Mashhad. The archaeological site, covering an area of about 20 hectares, consists of a well-known stone chāhār-tāq in the north, the remains of an architectural complex on the southern high mounds, two old graveyards, and a 10-hectare settlement that expanded once between the northern and southern mounds of the site (figs. 1 and 2).

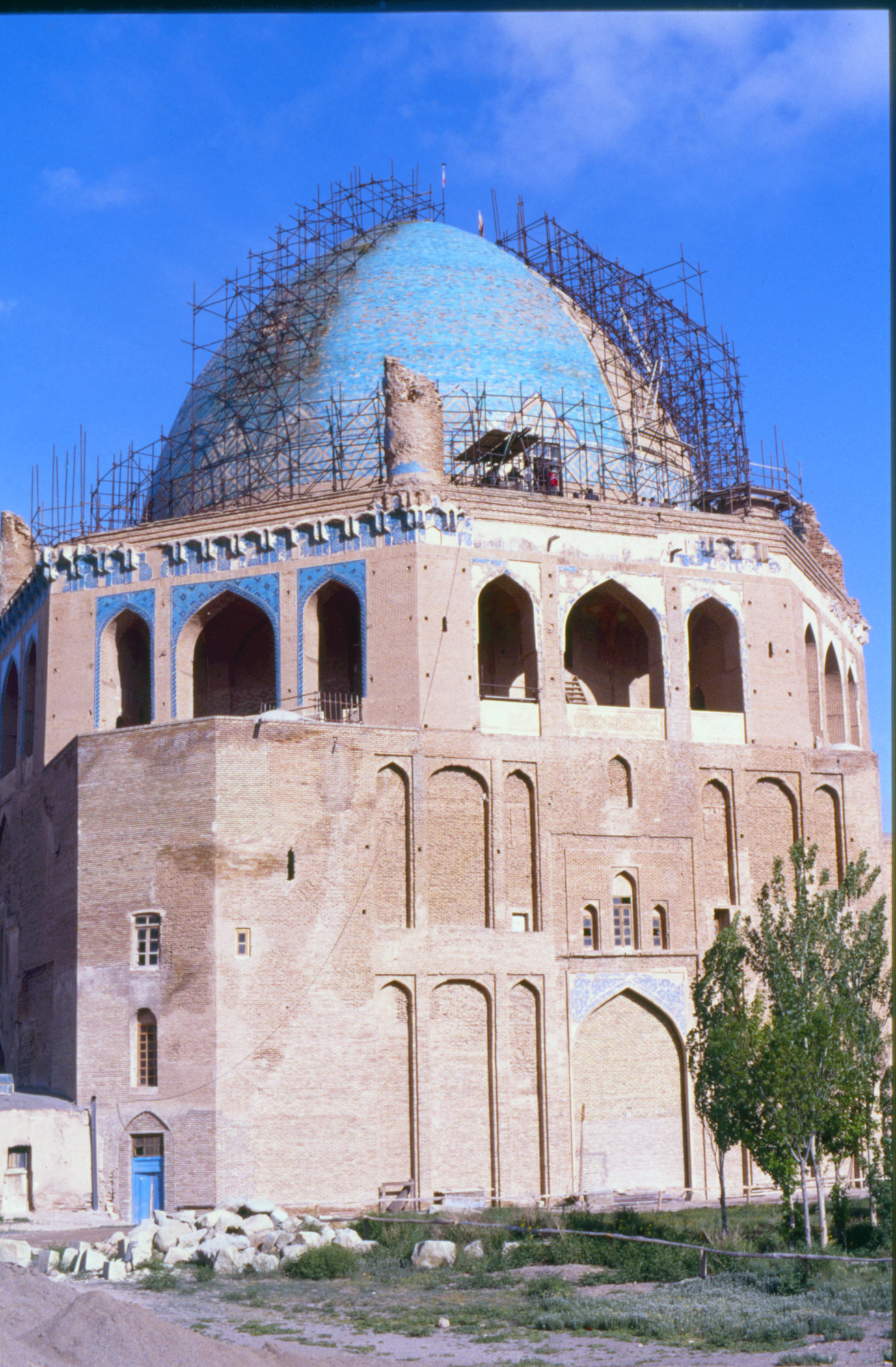

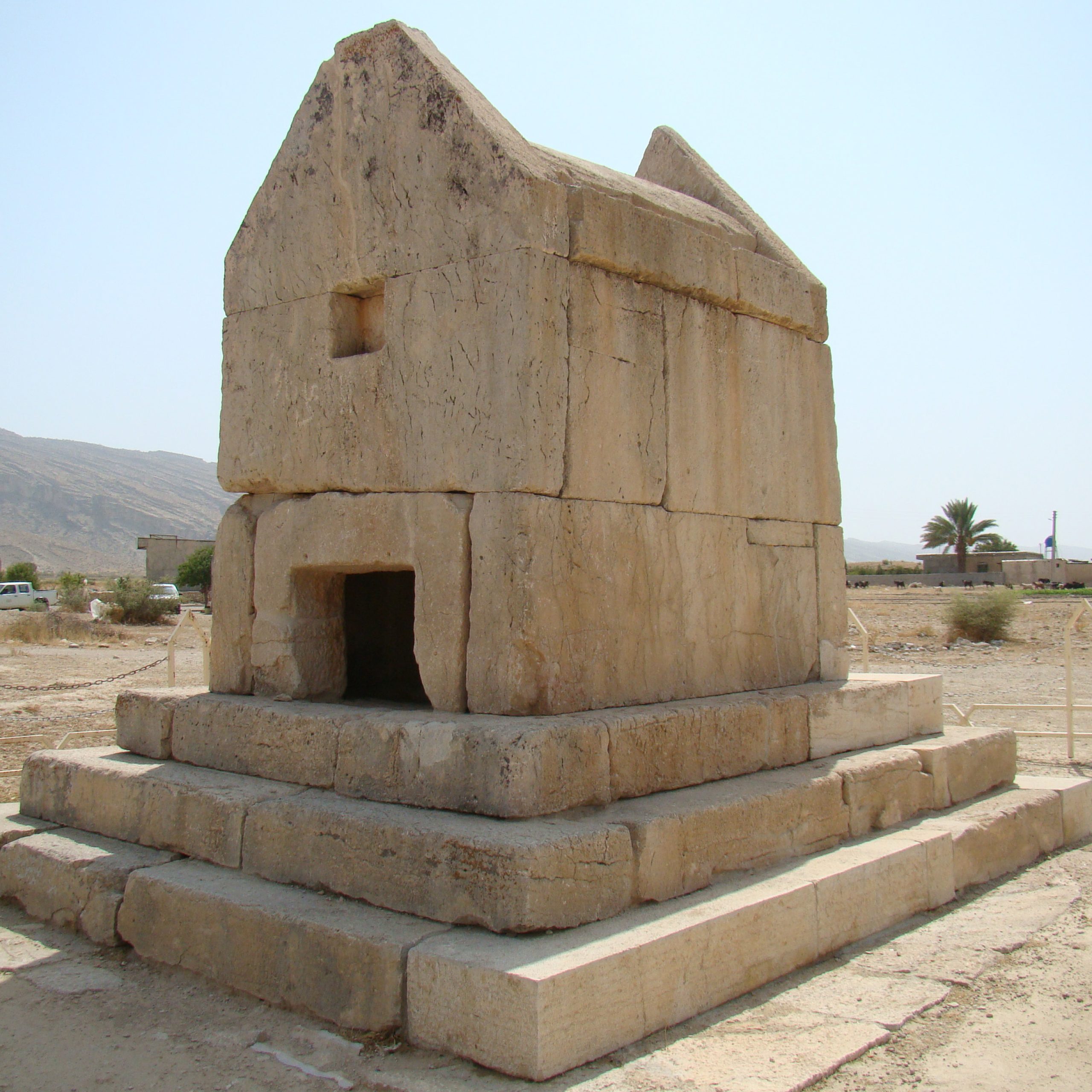

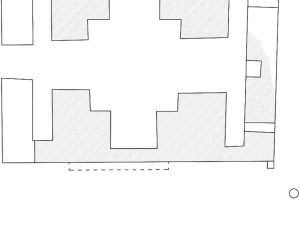

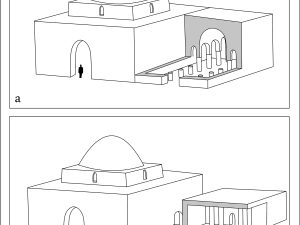

The chāhār-tāq (fig. 3) is built on top of a hill with irregular stones set in gypsum mortar. In spite of the large restoration of its structures in 1974, the monument still preserves its authentic architectural elements (fig. 4). There are four eyvāns, each 6.5 m. high, on the four sides of the building; they open onto the domed chamber that is roughly 7×7 m. (fig. 5). The dome rests on beams placed diagonally across the corners of the square room. Therefore, no squinches were employed for the transition between a square base and a circular dome (Huff, “Bāza-Ḵūr,” Encyclopedia Iranica). Archaeological excavations revealed that, unlike its current appearance, the western and eastern tāqs (vaulted entrance) of the main building were originally blocked by a north-south wall (for a full discussion, see Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in North-eastern Iran,” p. 264). Parallel to the southern tāq, an eyvān served as the main entrance and was separated from the southern tāq solely through a narrow east-west long room. The room identified on the northern side of the chāhār-tāq resembles the one on the southern side, both in width and length. Access to the northern room was provided through two narrow doorways in the northern wall (Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bāzeh-Hūr in North-Eastern Iran,” p. 268). Excavations in the north-eastern area of the chāhār-tāq resulted in the discovery of the remains of a columned building that abutted the eastern side of the chāhār-tāq (fig. 6). This hypostyle building possibly possessed at least 16 columns in two rows (Labbaf-Khaniki, "Trial Trenching and Discovery of a Columned Building in Bāzeh-Hūr (North-East Iran),” pp. 231-233). As Dietrich Huff suggests, the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq is a typical example of the third type of chāhār-tāqs: “It consists of the typical central domed unit with corner piers, arches, however, are closed by walls. Instead of an ambulatory, the central unit is partly or completely enclosed by rooms, eyvans, etc.; it may even occur freestanding” (Huff, “Sasanian Čahar Taqs in Fars,” p. 246). Three distinct construction phases have been identified in the Bāzeh-Hūr building. In the first phase, the chāhār-tāq itself was built. The construction of the hypostyle room dates most probably to the second phase. The blocking of the southern portico, the opening of the western tāq, and the leveling of the domed chamber floor and its covering with a new layer of gypsum and clay took place in the third phase. These phases can be relatively dated based on the surface ceramics. Accordingly, the chāhār-tāq was constructed during the early Sasanian period and was finally abandoned after a long period of use during the late Sāmānid period, that is in the 9th/10th century.

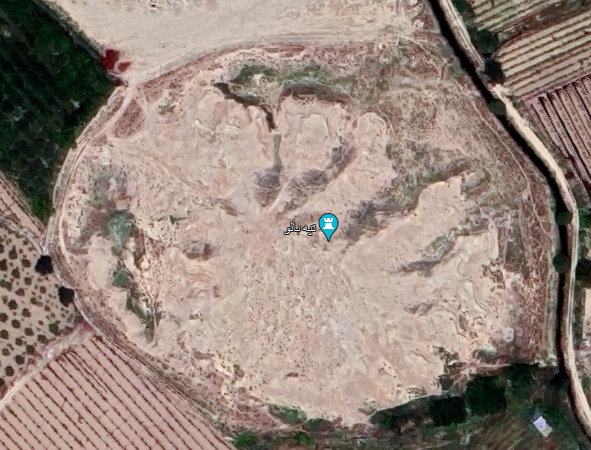

The remains of an architectural complex on the southern high mounds of the site are known as Qal’eh Dokhtar. They consist of four parts: 1) a complex on the north-western hill that was once erected on a platform of stone and gypsum, 2) a settlement on the north-western hillside, which was enclosed with a wall equipped with interval semi-circular bastions, 3) a linear mud-brick wall along the ridge of the hill adjoining several towers and keeps together, and IV) an open place in the southernmost of the mountain that was overlooked by two lateral towers (fig. 4). Archaeological excavations at Qal’eh Dokhtar in 2018 and 2019 revealed remains of a fire temple that consisted of a chāhār-tāq (interior space 7×7 m.), a rectangular anteroom, and an ambulatory space constructed with fine baked bricks and paved with a thick layer of gypsum. Inside the domed chamber, several ritual installations were found on the floor. A court/hall on the southeastern side of the fire temple was revealed that contains a basin-like structure surrounded by a row of columns. The columns were richly adorned with stuccoes. Abundant pieces of stuccoes and wall paintings which once decorated the walls and columns of the fire temple were also found due to the excavations. The preliminary results suggest that the fire temple was constructed in the late Parthian period and after three phases of alternation in the Sasanian period was abandoned in the early Islamic period (9th-10th century).

Fig. 1. General view of the historical site of Bāzeh-Hūr (photo: M. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Fig. 2. Topographic map of the site (after Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in north-eastern Iran,” p. 254, fig. 2)

Fig. 3. A view of the chāhār-tāq from the southwest (after Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in north-eastern Iran,” p. 254, fig. 1)

Fig. 4. The chāhār-tāq looking west (photo: M. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Fig. 5. Plan of the chāhār-tāq (after Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in north-eastern Iran,” p. 268, fig. 23)

Fig. 6. Two tentative reconstructions of the columned building abutting the main building of chāhār-tāq (reconstruction and drawing: M. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Archaeological Exploration

Located at 1800 m above sea level, Bāzeh-Hūr is on the main road connecting Mashahd to Torbat-e Heydariyeh and beyond in the direction of Kerman and Sistan. The first traveler who recorded his visit of the ruins is Henry Walter Bellew, a British physician serving in Afghanistan. In his journey in 1872, Bellew describes the remains of a stone chāhār-tāq in the northern sector of the site and refers to two or three domed houses situated on the mound just north of the chāhār-tāq (From the Indus to the Tigris, p. 354):

The crest of the hill on the right of this gorge is topped with the ruins of an ancient fort called Calae dukhtar. It looks down upon a domed chamber built of very solid masonry on the plain below, and called Darocsh -khána. Tradition assigns the fort as the retreat of some ancient king's beautiful daughter, whilst a devoted suitor pined away in unrequited love in the domed chamber. At the foot of the hills to the left are two or three similarly domed chambers. They stand on separate little mounds, and are called átash kadah, or " fire temple.” Farther out on the level stands an old sarae, and on a ridge of hill at the farther end of the valley, to the left, is the village of Rabáti Sufed.

Later, Mirza Qolām Hossein Khān Afzal al-Molk, a historian who lived during the reign of Muzaffar al-Din Shah (1896–1907), visited the Bāzeh-Hūr region and Robāt-e Sefid in 1903, and wrote (Afzal al-Molk, Safarname-ye Khorāsan va Kerman, p. 129):

Robat-e Sefid is located in the middle of a favourable pasture embraced by the mountains…the region is suitable for bivouacking and camping by the Khurasan governor…The village of Bāzeh-Hūr that hosts 200 families, is flourishing and there are too many cows and donkeys…

In 1923, Ernst Diez published the first photographs of the site as well as a short description of the chāhār-tāq. Because of the rudimentary construction methods used for the dome, he attributed the structure to the reign of Hormozd I (270–71/72) and his presence in Khorāsān in the early Sasanian period (Diez, Islamische Baukunst in Churasan, p. 39).

Ernst Herzfeld was the first archaeologist who visited Bāzeh-Hūr on the 25 of March 1925 and provided a detailed report on the ruins of chāhār-tāq. He described the masonry, structures, and architectural components of the chāhār-tāq, focusing on the construction methods of the dome. In his diary, Herzfeld recorded the chāhār-tāq as kaleh-i dukhtar (Qal’eh Dokhtar) and the fortifications to the south of the chāhār-tāq kaleh-i pisar (Qal’eh Pisar). In his view a "combination of the lower domed building and the terrace on top of the hill proves this building and others of its type to be fire temples" (Herzfeld, "Damascus: Studies in Architecture," p. 33). The chāhār-tāq of Bāzeh-Hūr is the first monument of Khorāsān to be registered on the Iranian National Heritage List in 1931. In a report published in 1938, André Godard proposed a new idea regarding the function of the chāhār-tāq (Godard, “Les monuments du feu,” pp. 53-58) and while hesitating to identify the chāhār-tāqs a fire temple, he dated the construction before the third century. Furthermore, he described the vaulting technique of the building in detail. In 1936 Donald Wilber visited the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq and published his observations in 1946. Like Godard, Wilber mentioned an ambulatory around the chāhār-tāq. He believed that the western taq of the building was the main entrance and the northern and southern tāqs once led to lateral rooms. The narrow corridor mentioned in Herzfeld's report was noted by Wilber as well. Herzfeld also pointed to four heaps of rubble, situated a few meters away from each other in a row at a short distance from the eastern side of the chāhār-tāq, which he interpreted as the remains of four huge columns. After describing Qalʿe-ye Dokhtar, he stated that the latter, as well as the chāhār-tāq, functioned as defensive installations that were constructed to protect Sasanian Khurāsān against southern raiders (Wilber, “The Ruins at Rabat-i-Safid”). In his valuable work on the fire temples of ancient Iran, Schippmann dated the chāhār-tāq to the early Sasanian period (Schippmann, Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtumer, pp. 13-21). In a comprehensive article published in 1975, Hallier provided a more extensive description of the remains of the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq and Qalʿeh Dokhtar. He also provided a plan in which, like Herzfeld, some columns are depicted on the eastern side of the chāhār-tāq (Hallier, “Ribat-i Sefid”). In a paper about Sasanian and Islamic chāhār-tāqs, Kleiss also described the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq and drew a plan showing the domed chamber and the remains of the eastern room. He also identified two long rooms on both the northern and southern sides of the chāhār-tāq and described the remains of the columns as engaged semi-cylinder columns that were partially incorporated into the eastern hall's walls (Kleiss, “Kuppel- und Rundbauten,” pp. 151-153).

In addition to the studies mentioned above, some other forms of documentation (including photographs, plans, sketches, and texts) were carried out by governmental organizations to protect and restore the chāhār-tāq during the last few decades. The file for the national registration of the chāhār-tāq was prepared in 1931 by André Godard who was then serving as director of the Iranian Archaeological Department (Edāre-ye kol-e ʿatiqāt). The file contains some quotations from Herzfeld, as well as two sketches showing the plan and buffer zone of the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq. One of them was drafted by Ya'ghoub Daneshdoust, who produced it for the chāhār-tāq 's restoration and reconstruction before 1965. Both plans show some new alterations to the original structure of the chāhār-tāq during restoration. According to the one-page report, some restoration was conducted before 1965. A Sasanian coin was also reported to have been found on the site surface.

Other scholars also offer descriptions of the Bāzeh-Hūr chāhār-tāq, again focusing on its vaulting system and function. In an article in Encyclopedia Iranica (s.v. Bāza-Ḵūr), Dietrich Huff collected records on the chāhār-tāq and its function made by earlier scholars and explorers who visited and studied the site during the last century (Huff, “Bāza-Ḵūr,” Encyclopaedia Iranica). Rajabali Labbaf-Khaniki has also described the apparent form of the chāhār-tāq and believed it was originally the central core of a complex (Labbaf-Khaniki, Simā-ye Mirās-e Farhangi-ye Khorāsān, pp. 42-43). Mohammad Karim Pirnia, after describing the structure and vault of the chāhār-tāq, interpreted the building as a pre-Sasanian temple (Pirnia, Sabk Shenāsi-ye Me'māri-ye Irāni, p. 108). More recently, Ali Hozhabri considered it as one of the similar structures in a chain of Sasanian fire temples and made some suggestions on the date and function of this construction (Hozhabri, “The Evolution of Religious Architecture”). A full discussion of previous archaeological research at the site is given in M. Labbaf-Khaniki, “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in North-Eastern Iran,” pp. 255-256. For the first time, Meysam Labbaf-Khaniki carried out archaeological excavations at Bāzeh-Hūr on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research from 2014 to 2019, of which the 2018 season was a joint expedition with the Louvre Museum.

Finds

Architectural remains of the Parthian (?), Sasanian and Islamic periods.

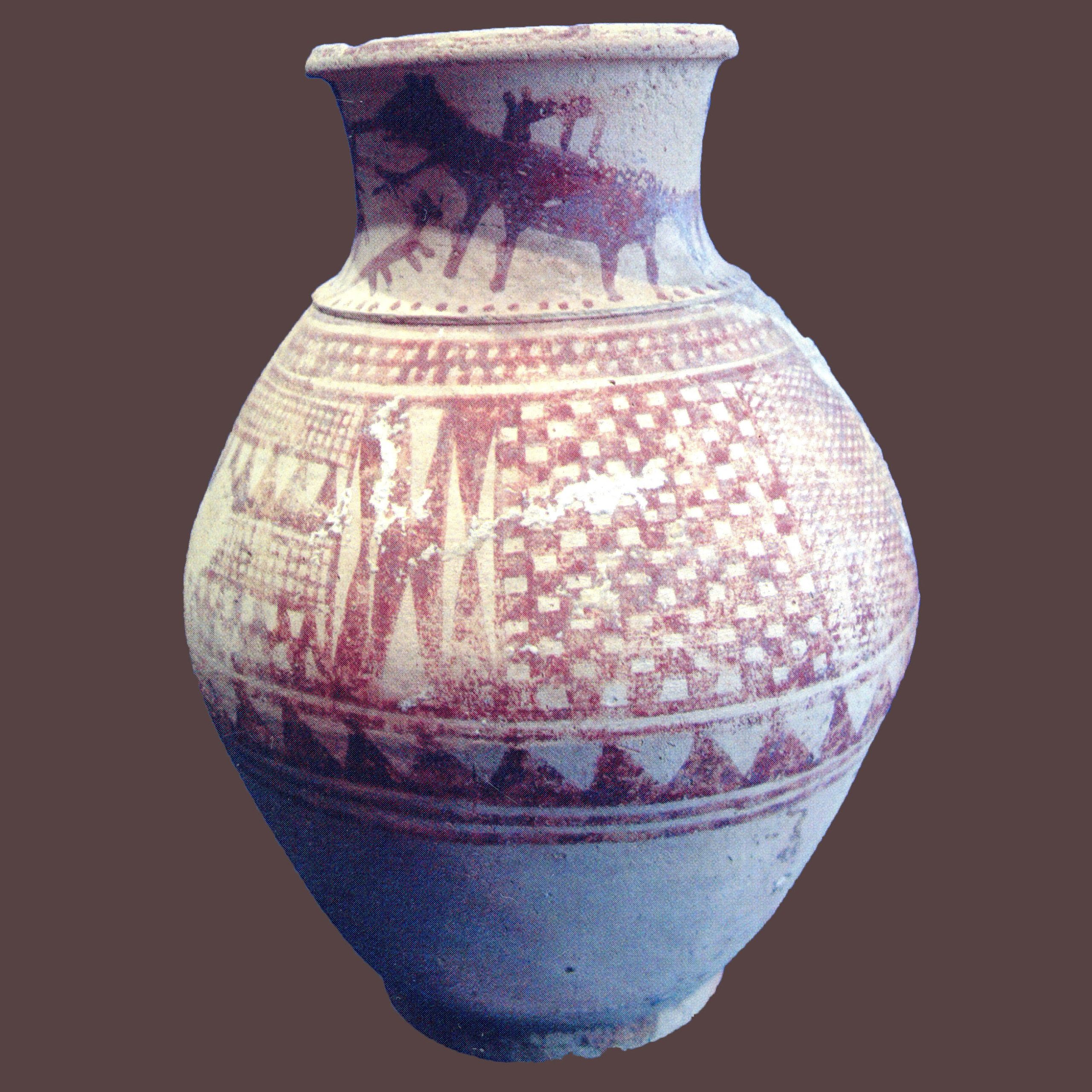

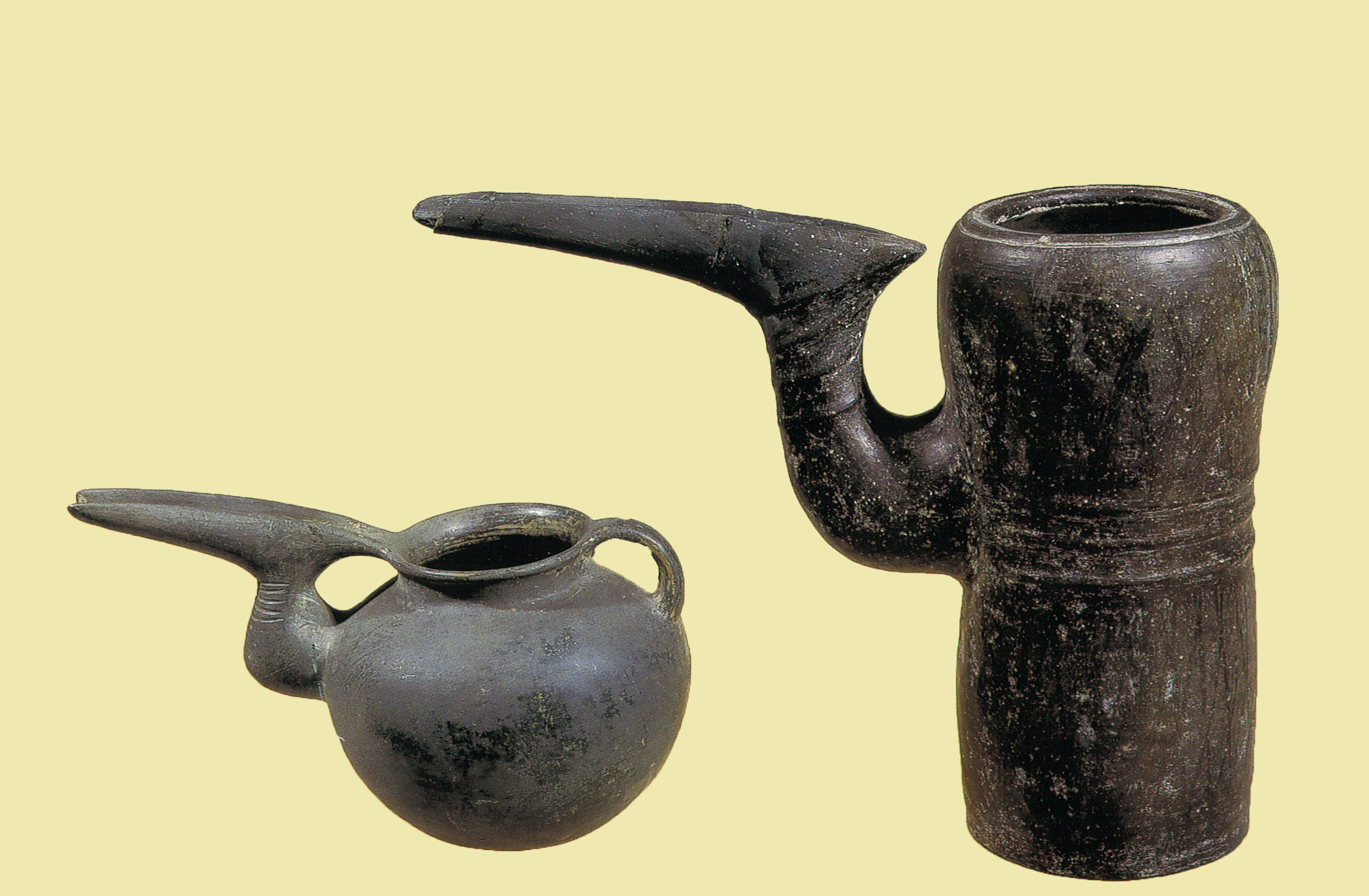

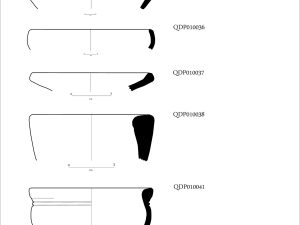

Diagnostic ceramic sherds of the Sasanian and early Islamic periods (fig. 7).

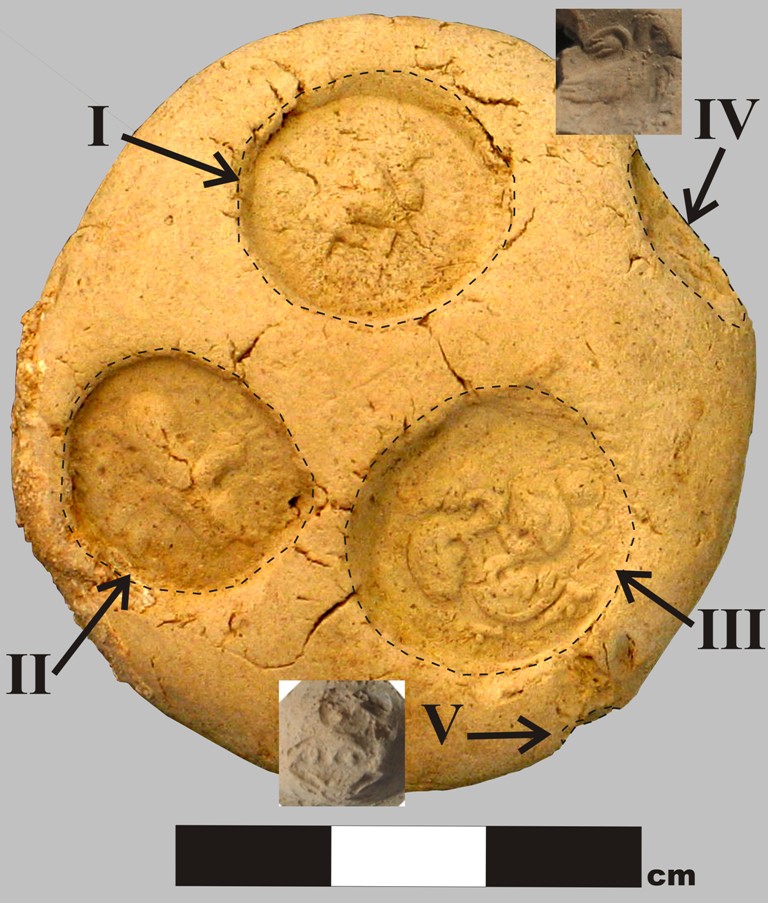

Remains of ritual installations including portions of the gypsum bases, stone-and-gypsum plinths, and brick platforms.

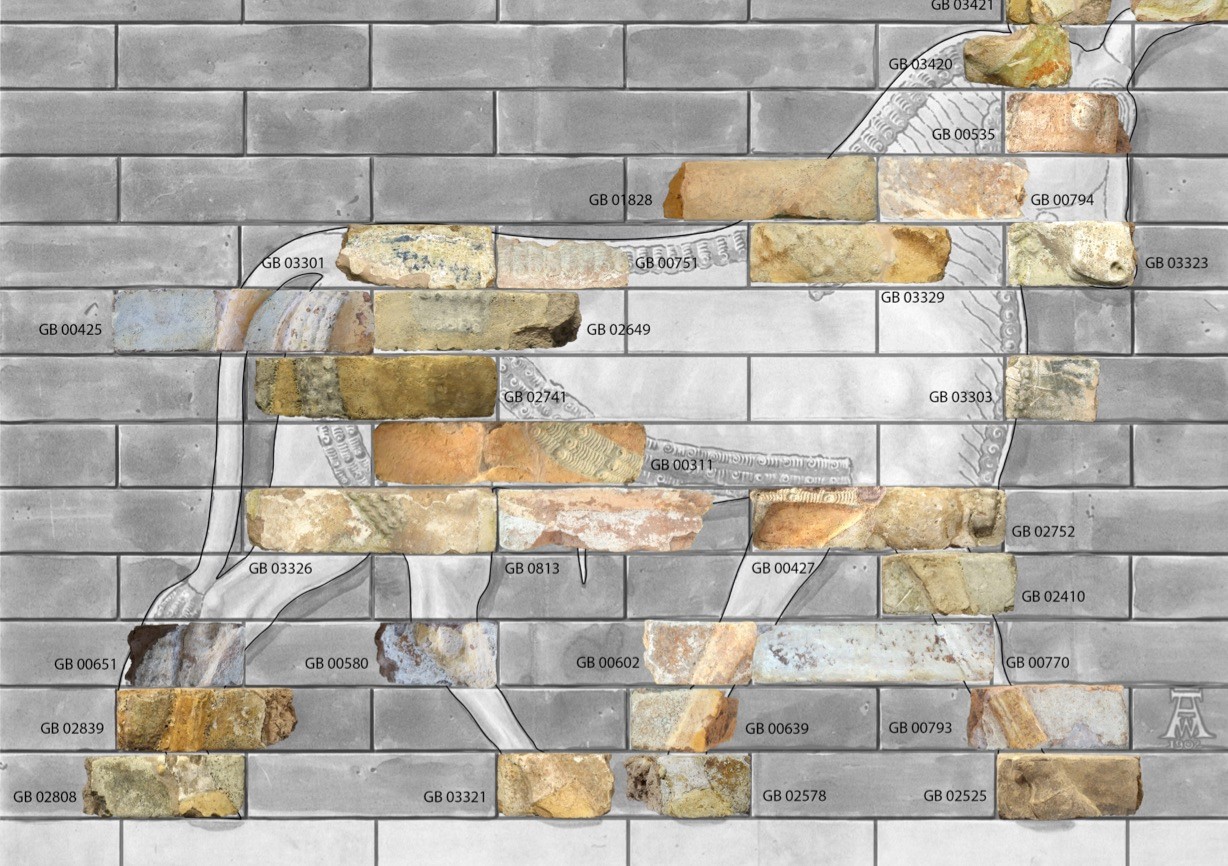

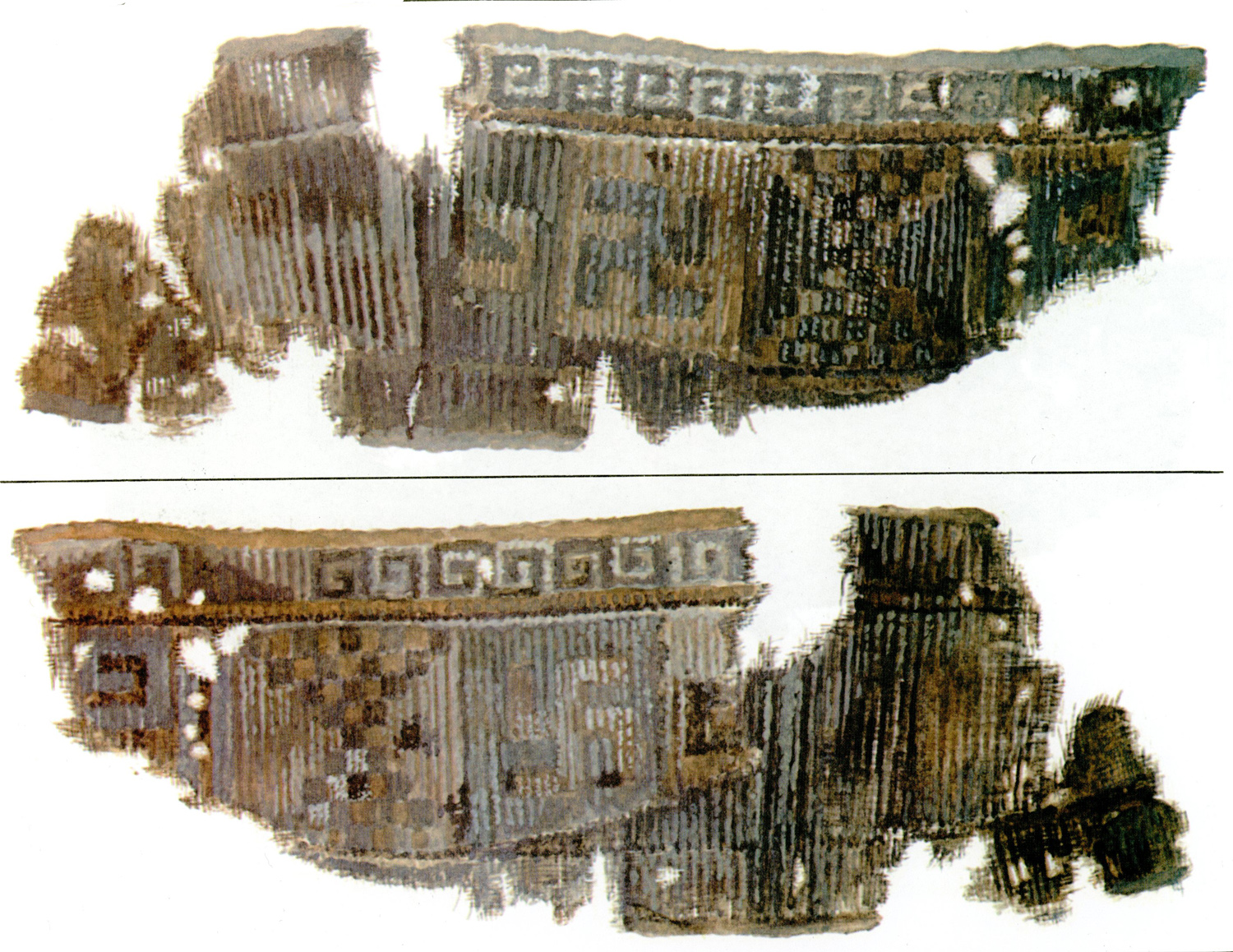

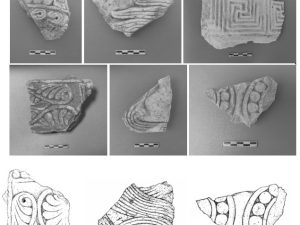

Stucco decorations (fig. 8) and pieces of wall paintings.

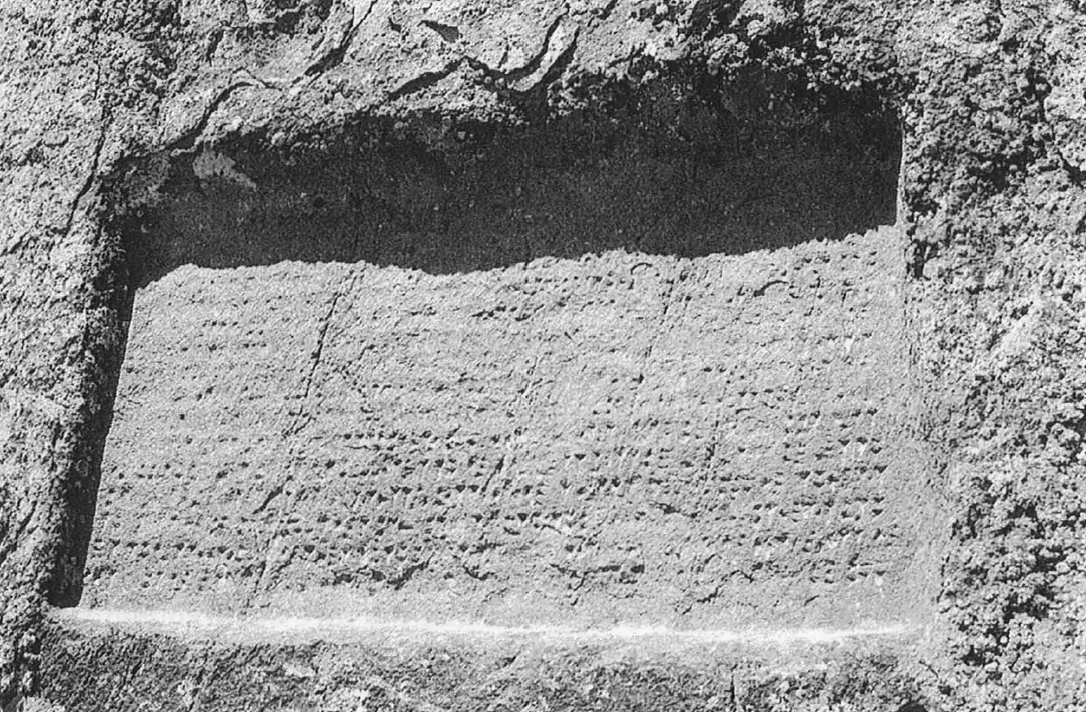

Middle Persian inscriptions were written in ink on the gypsum plasters (fig. 9).

Fig. 7. Samples of the ceramic sherds dating back to the Sasanian and early Islamic periods (photo and drawing: M. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Fig. 8. Stucco fragments from Qal’eh Dokhtar (photo: M. Labbaf-Khaniki; drawing: K. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Fig. 9. Fragment of an inscribed plaster from Qal’eh Dokhtar (photo: M. Labbaf-Khaniki)

Bibliography

Afzal al-Molk, G. H., Sāfarname-ye Khorāsān va Kerman, Gh. Roshani (ed.), Tehran, n.d.

Bellew, H. W., From the Indus to the Tigris, London, 1874.

Diez, E., Islamische Baukunst in Churasan, Hagen, 1923.

Godard, A., “Les monuments du feu,” In Athar-é Iran, vol. 3, Paris, 1938, pp. 49-51.

Hallier, U., “Ribat-i Sefid (Khorāsān),” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 8, 1975, pp. 143-166.

Herzfeld, E., “Damascus: Studies in Architecture,” Ars Islamica, vol. 9, 1942, pp. 1-53.

Huff, D., “The Sasanian Čahar Taqs in Fars,” In Proceedings of the Third Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, F. Bagherzadeh (ed.), Tehran, 1975, pp. 243–254.

Kleiss, W., “Kuppel- und Rundbauten aus sasanidischer und islamischer Zeit,” Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, vol. 11, 1978, pp. 151-166.

Labbaf-Khaniki, M., “Excavations at Bazeh-Hur in North-Eastern Iran: A Preliminary Report," Iran, vol. 55, 2017, pp. 253-270.

Labbaf-Khaniki, M., “Trial Trenching and Discovery of a Columned Building in Bāzeh-Hūr (North-East Iran)," Iran, vol. 58, 2020, pp. 221-235.

Labbaf-Khaniki, R., Simā-ye Mirās-e Farhangi-ye Khorāsān, Tehran, 1378/1999.

Pirnia, M. K., Sabk Shenāsi-ye Me'māri-ye Irāni, Tehran, 1386/2007.

Schippmann, K., Die Iranischen Feuerheiligtümer, Berlin, 1971.

Wilber, D. N., “The Ruins at Rabat-i-Safid,” Bulletin of the Iranian Institute, Nos. 6-7, 1946, pp. 22-28.