Mil-e Milegehمیل میله گه

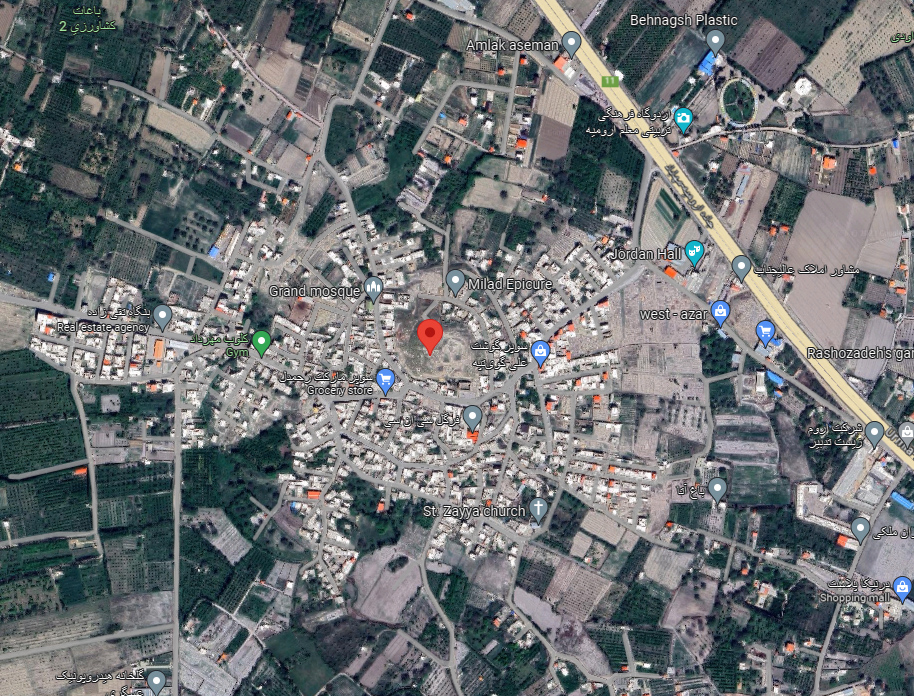

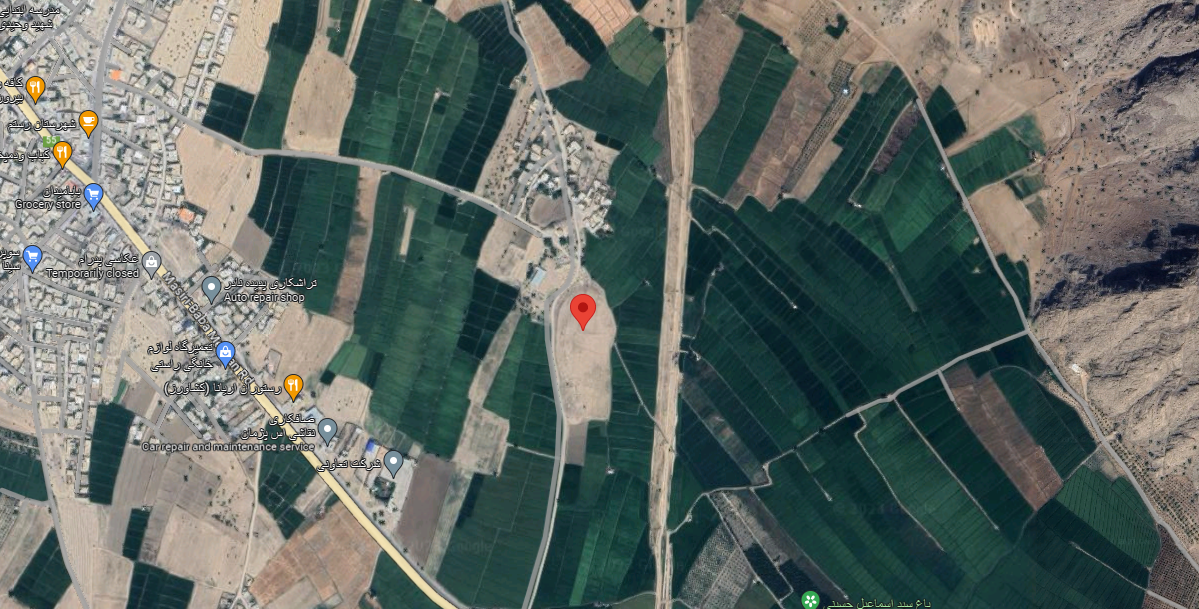

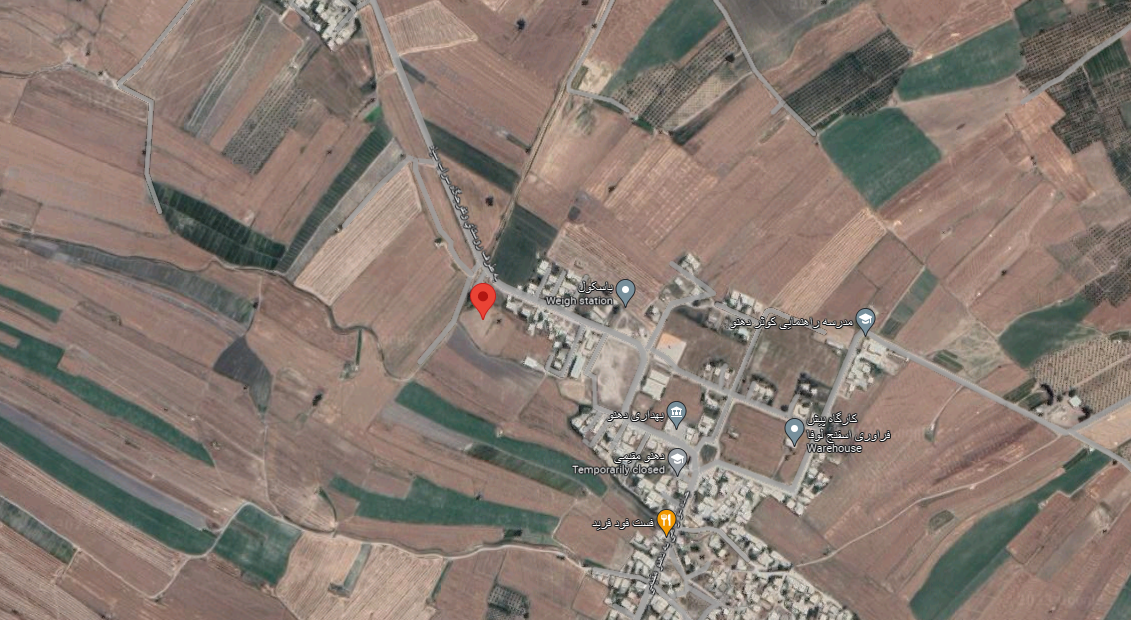

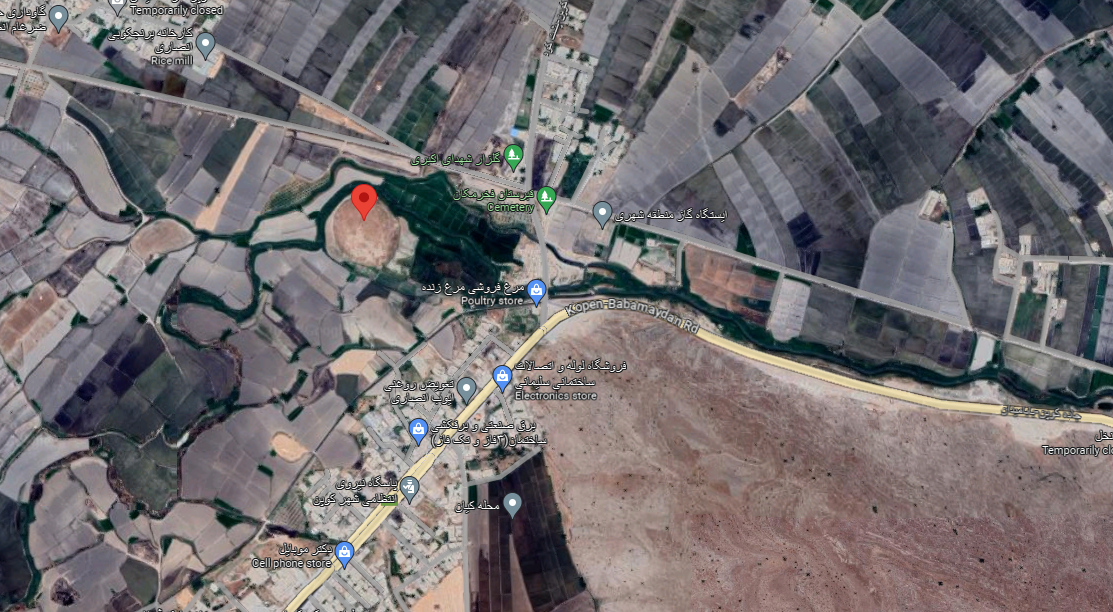

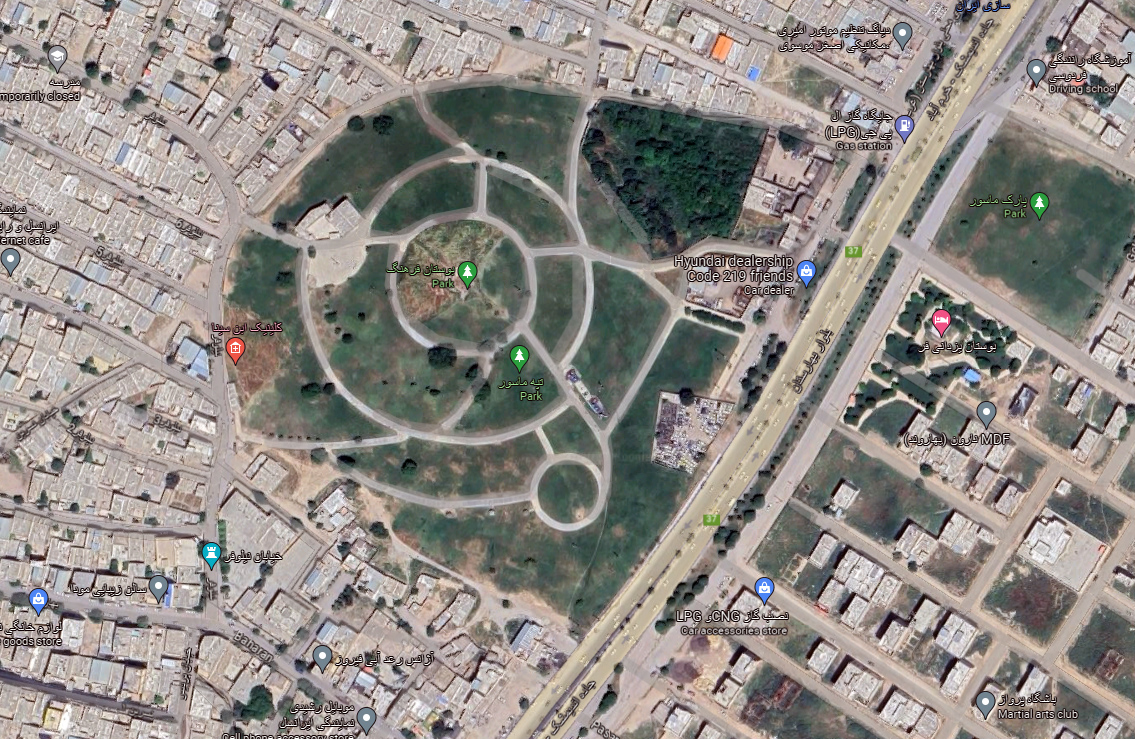

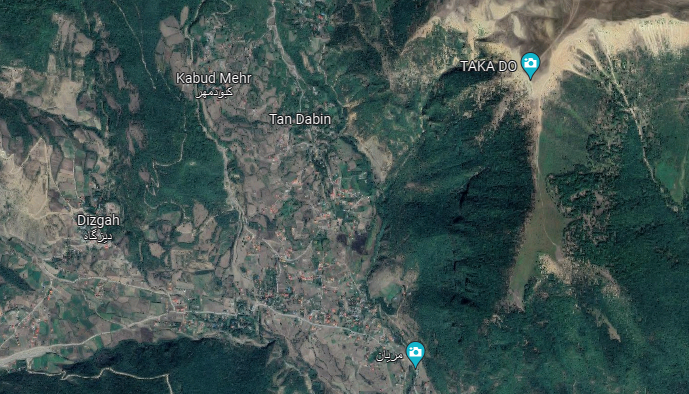

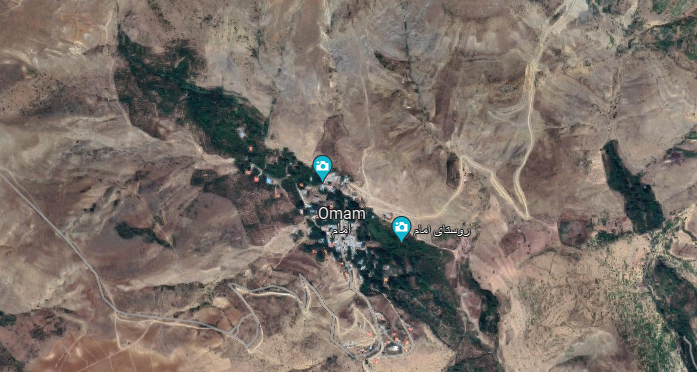

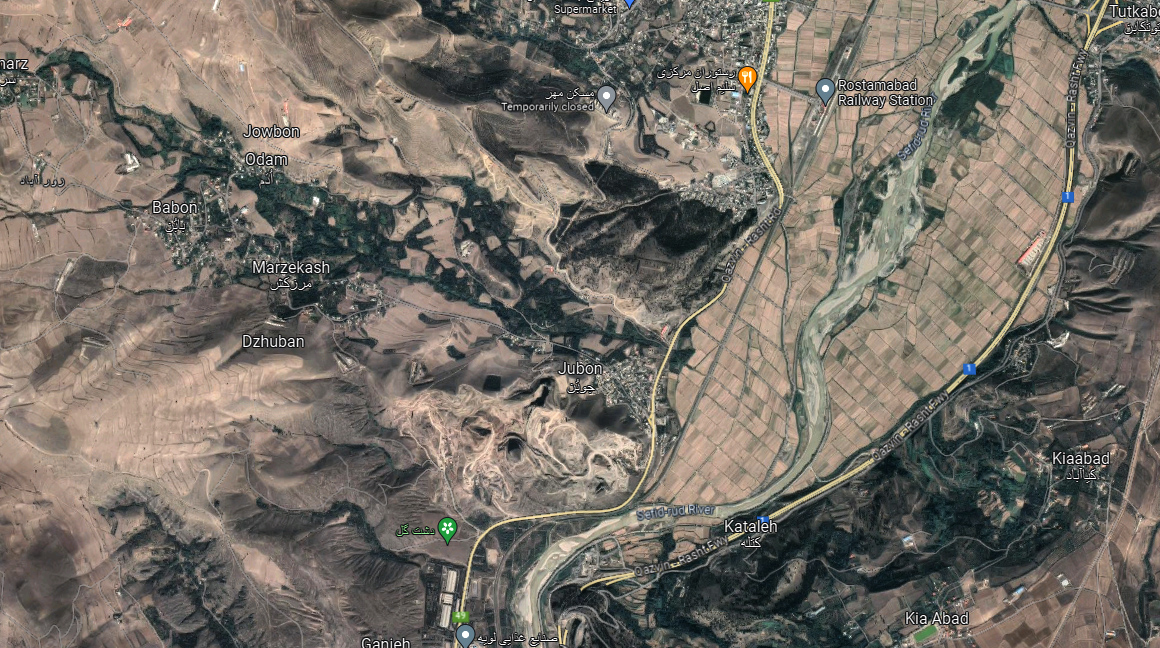

Location: The chāhār-tāq of Mil-e-Milegeh is located southeast of Eslāmābād-e-Ghārb, in western Iran, Kermanshah Province.

33° 57′ 02″N 46° 33′ 28″E

Mil-e Milegeh میل میله گه

Historical Period

Late Sasanian

History and description:

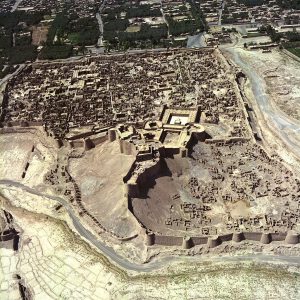

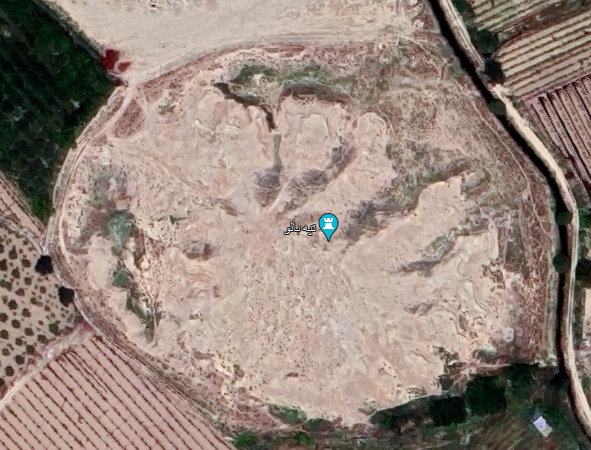

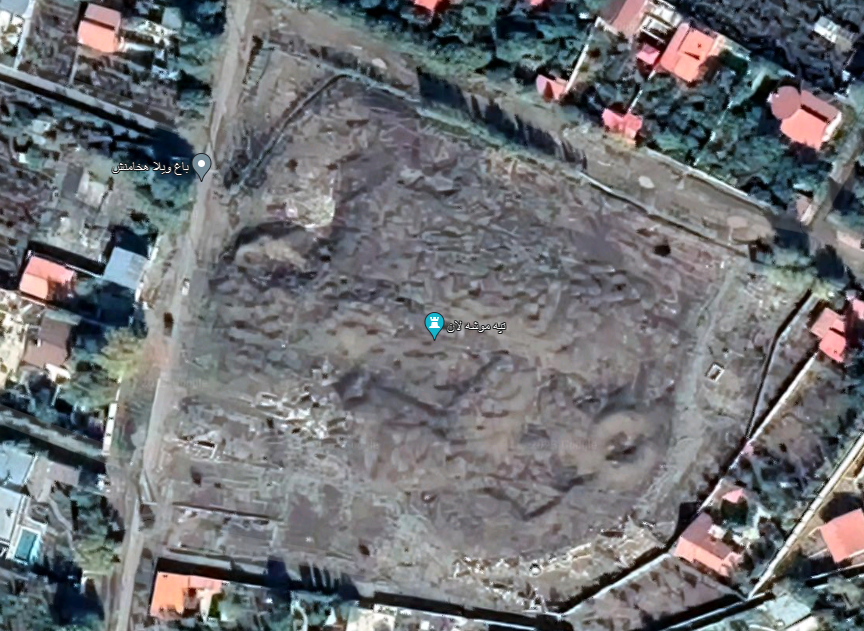

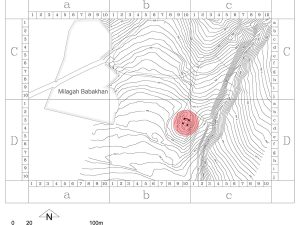

The chāhār-tāq of Mil-e-Milegeh is located 100 m east of the village of Siāh Siāh-e Milegeh Bābākhān, approximately 32 km southeast of the present-day town of Eslāmābād-e-Ghārb (formerly known as Shāhābād-e Gharb). The monument has not been mentioned in any historical record. The site of Mil-e Milegeh consists of a low, circular mound approximately 2.5 m high (figs. 1 and 2). In the past, the local people believed the mound to contain the tomb of a holy descendent of the eighth Imam of the Shiites.

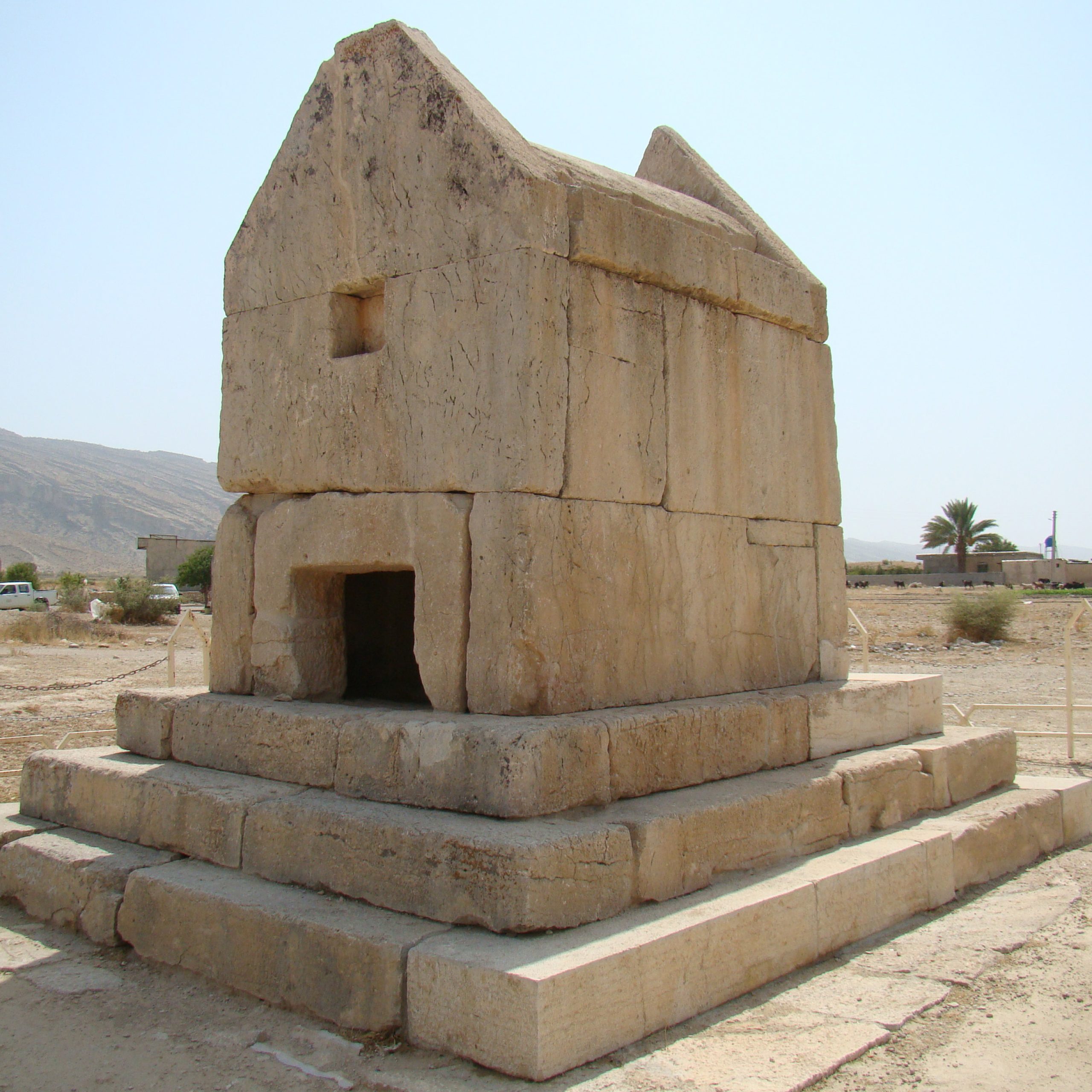

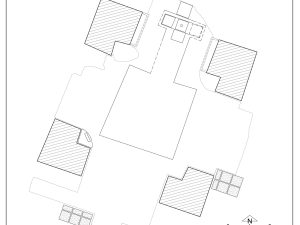

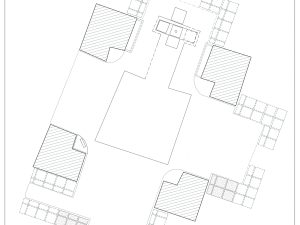

The main building represents a chāhār-tāq that consists of four corner pillars, standing at an average distance of 3.75 m apart. The central area of the chāhār-tāq is square in plan, measuring 5.05 m × 5.15 m, the corners of which are oriented toward the cardinal points (figs. 3 and 4). The chāhār-tāq lacks the ambulatory corridor that runs around the pillars in many other Sasanian chāhār-tāqs. Rather, here the chāhār-tāq was once flanked, at least on three sides, by mud-brick bays (figs. 5 and 6). While lacking an ambulatory corridor, the construction of the bays would have rendered this chāhār-tāq a closed building. This structural schema accords well with Zoroastrian tradition dictating that the sacred fire should not be exposed to the rays of the sun (Dhabhar, “The Persian Rivayats of Hormazyar Framarz and Others, pp. 56-57; Yamamoto, “The Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire in Archaeology and Literature (II),” p. 89; Keall, “Archaeology and the Fire Temple,” p. 17).

Nothing remains of the roof of this building; however, we can postulate a likely description based on comparisons with similar chāhār-tāqs. This comparative analysis suggests that four load-bearing arches would likely have spanned the areas between the corner piers and that a round dome on squinches would have covered the central square. This roofing structure was the most common method employed to cover similar chāhār-tāqs constructions, which were frequently made using rubble masonry.

Fig. 1. General view of the mound with the ruins of the chāhār-tāq (photo: Y. Moradi)

Fig. 2. Topographic map of the archaeological mound at Mil-e Milegeh (photo: Y. Moradi).

Fig. 3. Plan of the chāhār-tāq with surviving mud-bricks that surrounded the monument (photo: Y. Moradi).

Fig. 4. Plan of the chāhār-tāq with the reconstruction of the mud-brick floor that once surrounded the monument (photo: Y. Moradi).

Fig. 5. The chāhār-tāq from the south with mud-brick impressions left on the surrounding area. A stone slab is seen on the floor (photo: Y. Moradi).

Fig. 6. The chāhār-tāq from the east (photo: Y. Moradi).

Archaeological Exploration

During the 1970s, the local people illegally excavated the mound to uncover the grave of the Imāmzādeh (saint), and to build a burial chamber. This excavation resulted in the discovery of a chāhār-tāq and several remains with cultic significance (figs. 1 and 2). The chāhār-tāq has since become a site of pilgrimage, with residents of the village of Siyāh Siyāh-e Milegeh Bābākhān and nearby regions visiting the site to make offerings. (Moradi, “Chāhār-tāqi-ye Mil-e Milegeh”, pp. 155-156; “On the Sasanian fire temples,” p. 73). Archaeologists from the local branch of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization made a preliminary survey of the monument in 1998. In 2006, Shahram Alyari, a local archaeologist based in Eslāmābād-e Gharb informed the author on the site’s structures. A brief visit to the site resulted in the publication of a preliminary report (Moradi, “Chāhār-tāqi-ye Mil-e Milegeh”). In 2009, the author carried out excavations at the site on behalf of the local branch of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization in Kermanshah.

The excavations at Mil-e Milagah provide a significant body of information about the installations within the inner area of the sanctuary (the chāhār-tāq). The installations have close parallels in the fire temples of Shiyān and Palang Gerd. However, these comparative sites do not greatly assist in determining the precise function of these cult installations, as the examples discovered from each of these sites are the first known examples of this type of installation, and their functional and ritual implications are as yet unknown.

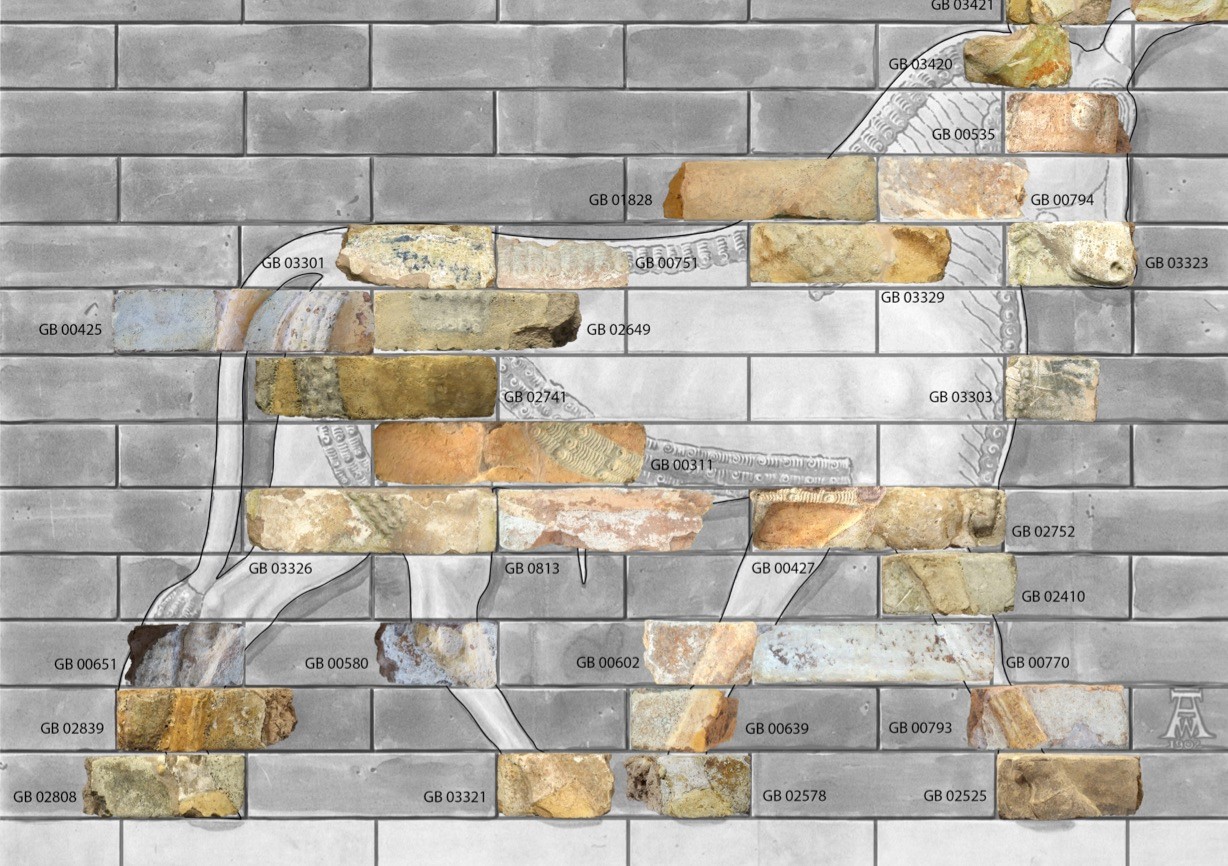

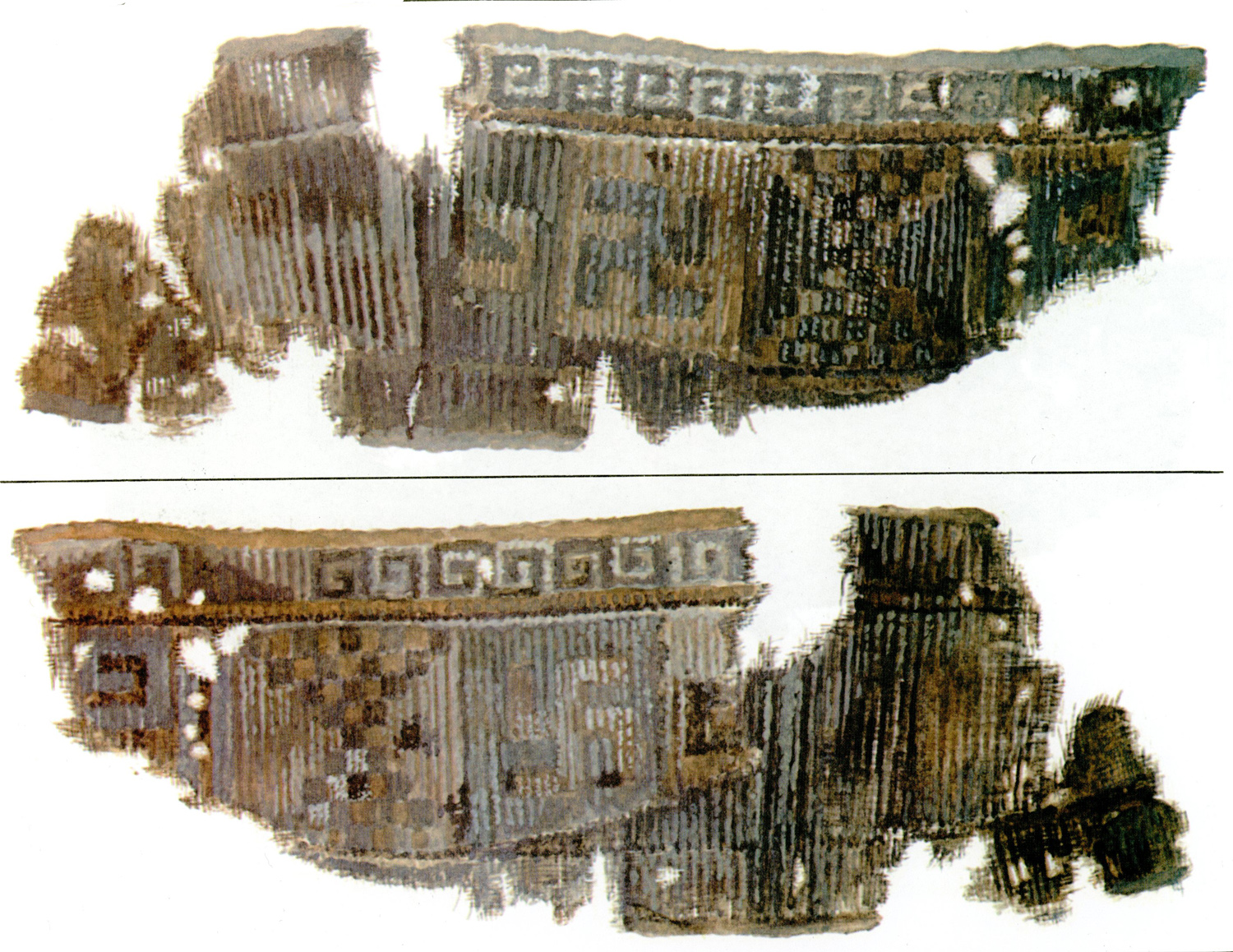

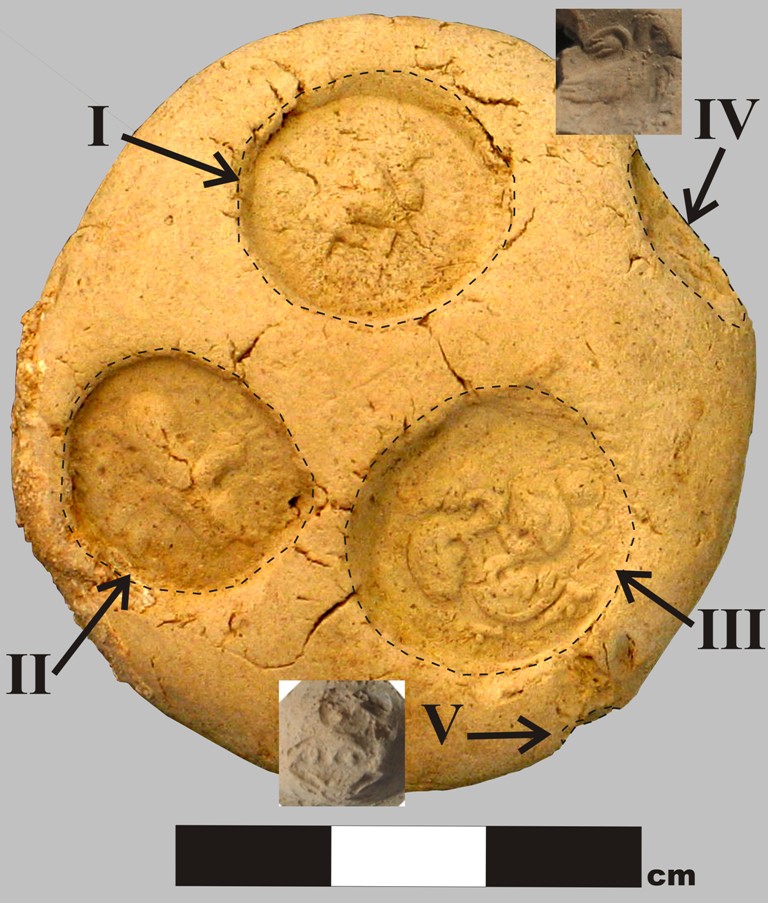

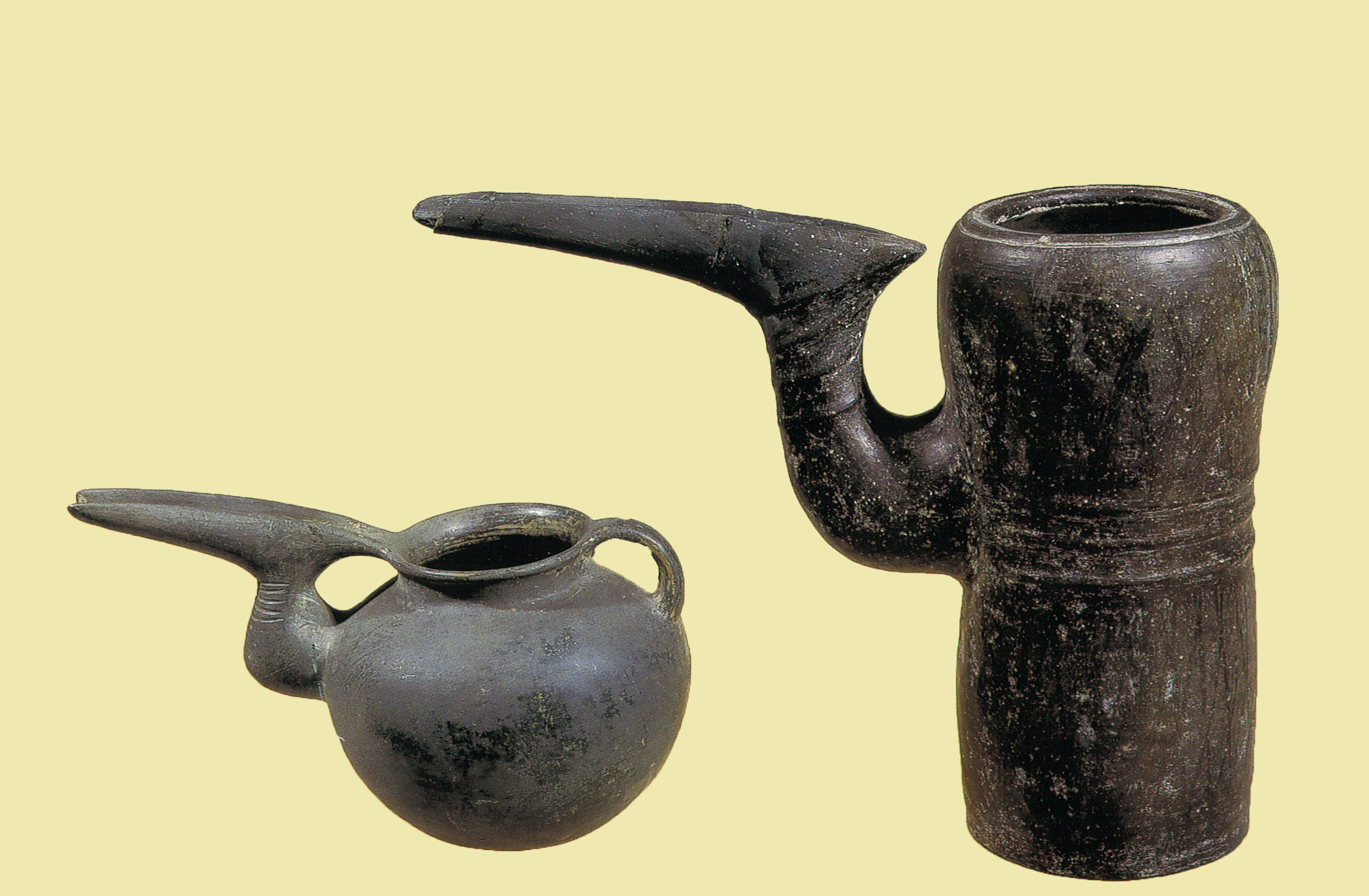

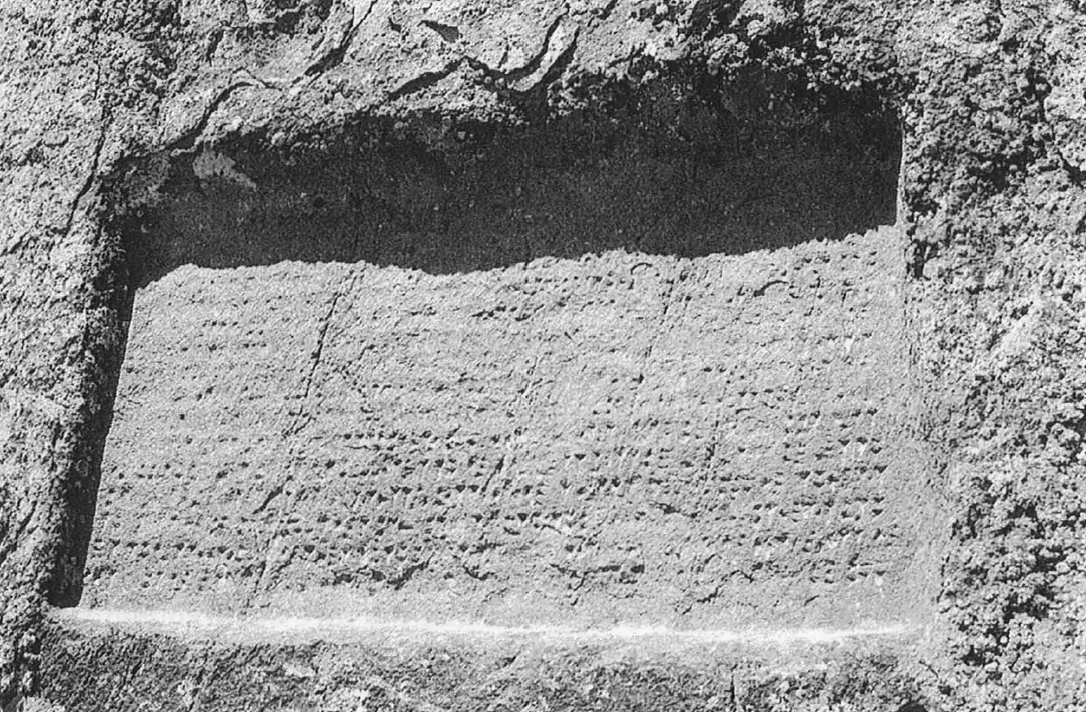

The installations found in the inner area of the chāhār-tāq of Mil-e Milegeh include a low platform, a few gypsum stands, and four stone bases. The platform was constructed from rubble stone embedded in gypsum mortar (fig. 7). It consists of two sections: a ‘square’ and a ‘T-shaped’ section. The square section measures 3.56 in length, 3.48 in width, and 10 cm in height. The T-shaped section extends for 50 cm outside the chāhār-tāq perimeter. The stem of the T-shaped platform measures 2.23 m × 1.15 m bearing remnants of a masonry podium (56 × 48 × 20 cm). The branched part of the T-shaped platform is 2.05 m long and 75 cm wide. This part bears lower portions of three gypsum stands, each 19 cm apart (fig. 8). Of these three stands, the middle one is better preserved, and is square (49 cm by 49 cm with an existing height of 15 cm) and embellished with flutes on each side (fig. 9). This stand contains a hole measuring 10 cm in diameter. Five fragmentary stands of this type were scattered inside the chāhār-tāq (figs. 10 and 11). It is not clear whether these fragments belonged to the stands that had been inserted in the branched part of the T-shaped platform, or whether the stands to which these fragments belong had originally been positioned on the stem of the T-shaped platform, as in the example of the fire temple of Shiyān (Rezvani, Gozāresh-e kāvosh-e nejātbakhshi-ye mohavatte-ye sadd-e Shiyān, pp. 50 and 74, fig. 70; Atashkadey-e Shiyān,).

The stands from Mil-e Milegeh bear a remarkable resemblance to those recovered from the fire temples of Shiyān (Rezvani, Gozāreh-e kāvosh-e nejātbakhshi-ye mohavatte-ye sadd-e Shiyān, Kermanshāh, fig. 91; Atashkadey-e Shiyān,), Palang Gerd (Khosravi, Alibaigi, and Rahbar, “The Function of Gypsum Bases in Sasanid Fire Temples,” pls. 5-6), and Qaleh-ye Kohzād (Motamedi, “Mehrābeh-ye Vizenhār, Qaleh-ye Kohzād,” pp. 11-12). Parallels to these stands were also found at the site of Imāmzādeh Hāsel Zālemi in Fārs (Askari Chaverdi, “Madāreki az jonub-e Fārs dar zaminey-e takrim-e ātash dar Iran-e bāstān,” pp. 28-30, figs. 3, 5-6, for further examples, see Moradi, “On the Sasanian Fire Temples,” pp. 83-84).

The immediate impression conveyed by the size and shape of the stands is that they may have served as fire altars upon the flat top of which may have been placed a metal vessel containing the sacred fire. However, this assertion cannot be substantiated because according to Zoroastrian tradition two sacred fires cannot be allowed to burn in sight of one another (Boyce “On the sacred fires of the Zoroastrians,” p. 55; Huff, “Takht-i Suleiman. Sasanian Fire Sanctuary and Mongolian Palace,” p. 467; “The Functional Layout of the Fire Sanctuary at Takht-i Sulaimān,” p. 4). Although the original shape of these stands is unknown, three possibilities can be considered. 1) Based on the numismatic evidence and cultic banners in present-day Pārsi fire temples, they served as a base that held a standard/banner or drafsh (Cribb, “Numismatic evidence for Kushano-Sasanian chronology,” pls. 1-2, 5; Herzfeld, “Kushano-Sasanian Coins,” pls. I. 7b, III. 18a, 19b, 22a; De Jong, “Vexillologica Sacra: Searching the Cultic Banner,” p. 193). The second possibility is that each stand served to hold an incense burner or other instruments related to the religious ceremonies that were performed within the chāhār-tāq. The third possibility is that the stands served as legs of a takht or throne, upon which sacred implements and utensils would have been laid.

The excavation also yielded a stone slab that is 72 cm wide, 1.15 m long in its current state, and 10 cm thick (fig. 5). A comparable example of this slab was unearthed from the fire temple of Shiyān (Rezvani, Gozāresh-e kāvosh-e nejātbakhshi-ye mohavatte-ye sadd-e Shiyān, fig. 110). It seems that the stone-slab being a table (ḵān, or ḵwān) is used in the main fire chamber to hold a fire altar, and also in the yazišngāh, upon which are placed the religious utensils required in the liturgical services of the Yasna (for a full discussion, see Moradi, “On the Sasanian Fire Temples,” p. 86).

Other finds consist of two plaster cases that stand along the northeast and northwest pillars. Each case is 1.48 m long and 27 cm wide and has an existing depth of 7 cm. The walls of the cases are 8 cm thick. Plaster cases of this type have also been reported from the fire temples of Shiyān and Palang Gerd. The cases from Palang Gerd contained human bones (Khosravi “Shavāhedi az tadfin-e dowre-ye sāsāni,” pp. 127-130, figs. 19-25 ), indicating that they had served as astodāns (ossuary). Accordingly, it is reasonable to postulate that the cases found from the fire temples of Shiān and Mil-e Milegeh may also have served as astodāns. Classic examples of this type of funerary case were also found in the complex of Bandiān (Rahbar, “Le monument sassanid de Bandiān, Dargaz,” pp. 11-13, figs. 5-7; “The Discovery of a Sasanian Period Fire Temple at Bandyān, Dargaz,” pp. 19-20, figs. 16-21).

Another notable feature in Mil-e Milegeh’s chāhār-tāq is four stone bases (fig. 12). While two of these bases are broken, they all were of equal shape and size. Although the bases were found in the chāhār-tāq, it is difficult to determine whether they were part of the structure, or whether they were subsequently brought there. If the former is the case, they may have served as column bases that originally stood on the four corners of the square platform to support a canopy structure beneath the dome of the chāhār-tāq, and that this canopy structure would have housed the fire altar (for discussion and further evidence, see Moradi, “On the Sasanian fire temples,” p. 86).

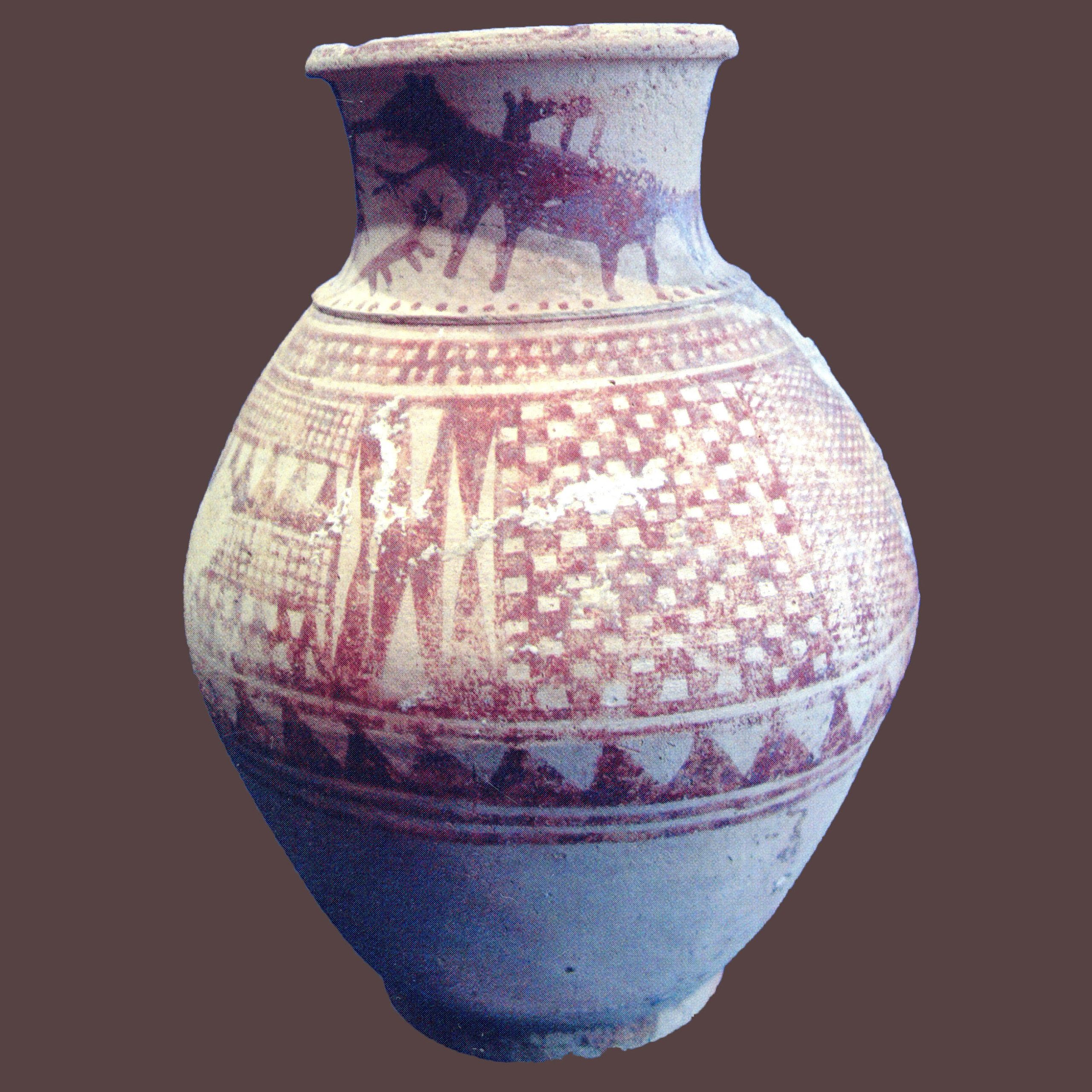

No compelling evidence was recovered during the recent archaeological excavations to cast light upon the precise construction date of the chāhār-tāq at Mil-e Milegeh. Although a substantial number of pottery sherds were found in the chāhār-tāq, they cannot be considered diagnostic and do not allow for the precise dating of the chāhār-tāq, as these sherds could date to any time during the Sasanian period. Additionally, the ground plan of the chāhār-tāq does not reveal any evidence of specific construction date, as this type of plan was commonly used in fire temples throughout the Sasanian period. While the cult installations recovered at Mil-e Milegeh—including the platform and the decorated stands—are almost identical to those recovered from the fire temples of Shiyān and Palang Gerd; they cannot be taken as an indicative of the construction date of the chāhār-tāq, as the precise construction date of these reference fire temples also remains obscure. Although there is insufficient evidence to suggest a construction date for these fire temples, one can safely claim that each of these fire temples continued to be in use until at least the collapse of the Sasanian dynasty. This assumption is supported by the presence of pottery found in these fire temples, dating to the 6th and 7th centuries.

Fig. 7. The platform with gypsum stands and stone column bases (photo: Y. Moradi)

Fig. 8. Gypsum stands (photo: Y. Moradi)

Fig. 9. One of the fluted stands (photo: Y. Moradi)

Fig. 10. Fragment of a fluted stand (photo: Y. Moradi)

Fig. 11. Fragment of a fluted stand (Y. Moradi)

Fig. 12. Stone column bases (photo: Y. Moradi)

Find:

Finds consist of fragments of stucco decorations, cultic stands in gypsum, stone bases, plaster troughs or cases possibly used as ossuaries.

Bibliography

Askari Chaverdi, A., “Madāreki az jonub-e Fārs dar zaminey-e takrim-e ātash dar Iran-e bāstān”, Iranian Journal of Archaeology and History, No. 49, 1390/2011, pp. 27-39 (in Persian with abstract in English).

Cribb, J., “Numismatic Evidence for Kushano-Sasanian Chronology”, Studia Iranica, vol. 19, 1990, pp. 151-193, pls. I-VIII.

De Jong, A. “Vexillologica Sacra: Searching the Cultic Banner”, in: C. Cereti, M. Maggi, and E. Provasi (eds.), Religious Themes and Texts of Pre-Islamic Iran and Central Asia: Studies in Honour of Professor Gherardo Gnoli on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday on 6th December 2002, Wiesbaden, 2003, pp. 191-202.

Dhabhar, B. N., The Persian Rivayats of Hormazyar Framarz and Others, Bombay, 1932.

Herzfeld, E., “Kushano-Sasanian Coins”, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 38, 1930, pp. 1-51.

Huff, D., “The Functional Layout of the Fire Sanctuary at Takht-i Sulaimān,” in Current Research in Sasanian Archaeology, Art and History. Proceedings of a Conference held at Durham University, November 3rd and 4th, 2001 organized by the Centre for Iranian Studies, IMEIS and the Department of Archaeology of Durham University, D. Kennet and P. Luft, (eds.), Oxford, 2008, pp. 1-13.

Huff, D., “Takht-i Suleiman. Sasanian Fire Sanctuary and Mongolian Palace”, in Persiens Antike Pracht: Bergbau, Handwerk, Archäologie; Katalog der Ausstellung des Deutschen Bergbau-Museums Bochum vom 28. November 2004 bis 29. Mai 2005, T. Stöllner, R. Slotta, and A. Vatandoust (eds.), Bochum, 2004, pp. 462-471.

Keall, E. J., “Archaeology and the Fire Temple”, in Iranian Civilization and Culture, C. J. Adams (ed.), Montreal, 1972, pp. 15-22.

Khosravi, Sh., “Shavāhedi az tadfin-e dowrey-e sasani dar Plang Gerd”, in Bāstanpazhuh, M. Khanipour and R. Nasseri (eds.), 1396/2016, pp. 119-146.

Khosravi, Sh, S. Alibaigi, and M. Rahbar, “The Function of Gypsum Bases in Sasanid Fire Temples: A Different Proposal,” Iranica Antiqua, vol. 53, 2018, pp. 267-298.

Moradi, Y., “Chāhār-tāqiy-e Mil-e Milagah: ātashkadeh’i az dowre-ye sāsāni,” Majale-ye Motāle’āt-e Bāstānshenāsi, vol. 1, No. 1, 1388/2009, pp. 155-183 (in Persian with abstract in English).

Moradi, Y., “On the Sasanian Fire Temples: New Evidence from the Chāhār-tāq of Mil-e-Milagah”, Parthica, vol. 18, 2016, pp. 73-95.

Motamedi, N., “Mehrābeh-ye Vizenhār, Qaleh-ye Kohzād”, Mirās-e Farhangi, No. 5, 1371/1992, pp. 8-15.

Rahbar, M., “Le monument sassanide de Bandiān, Dargaz: Un temple du feu d’après les dernières découvertes, 1996-98”, Studia Iranica, vol. 33, 2004, pp. 7-30.

Rahbar, M., “The Discovery of a Sasanian Period Fire Temple at Bandyān, Dargaz”, in: D. Kennet and P. Luft (eds.), Current Research in Sasanian Archaeology, Art and History, Oxford, 2008, pp. 15-40.

Rezvani, H., Gozāreh-e kāvosh-e nejātbakhshi-ye mohavatte-ye sadd-e Shiyān, Kermanshāh, The Iranian Center for Archaeological Research, Tehran, 1384/2005 (unpublished report in Persian).

Rezvani, H., Atashkadey-e Shiyān, Kermanshah, 1385/2006 (in Persian).

Yamamoto, Y., “The Zoroastrian Temple Cult of Fire in Archaeology and Literature (II),” Orient, vol. 17, 1981, pp. 67-104.