Gelālak / Dastowā / Shushtarگلالک/دستوا/شوشتر

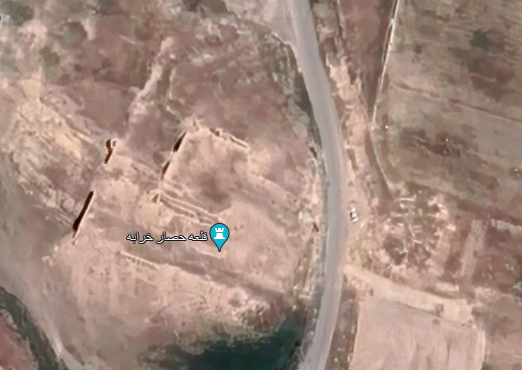

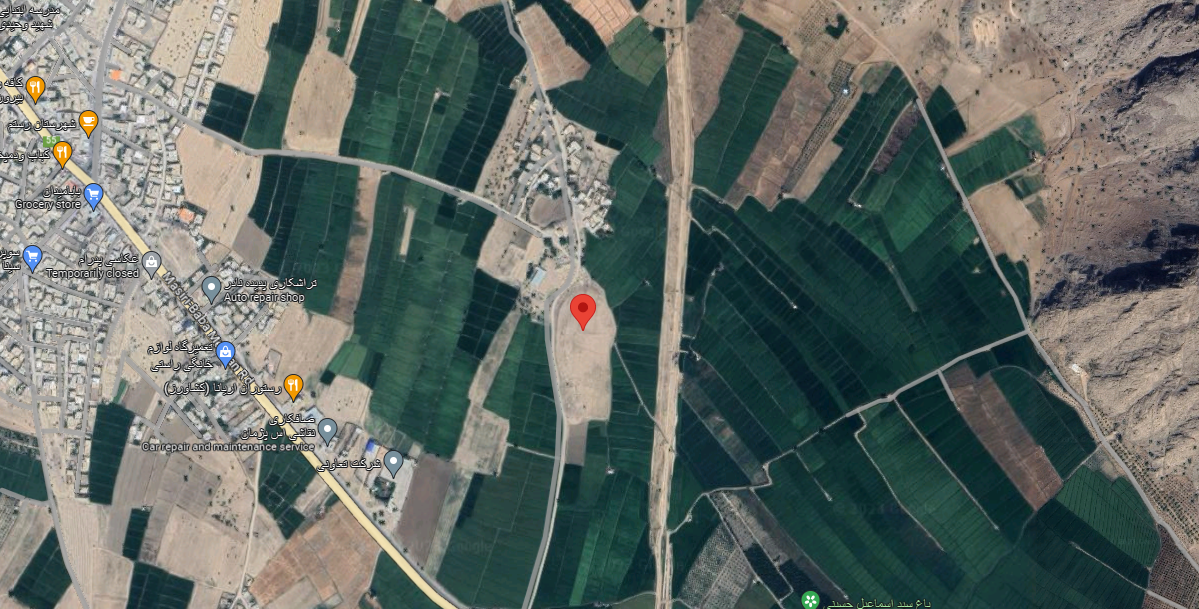

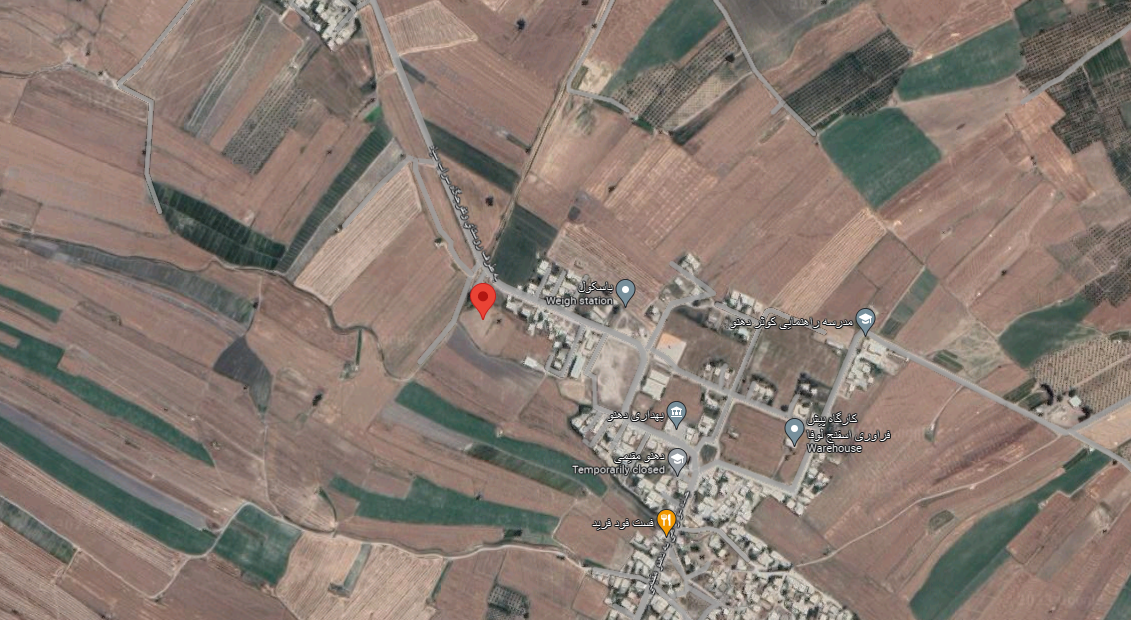

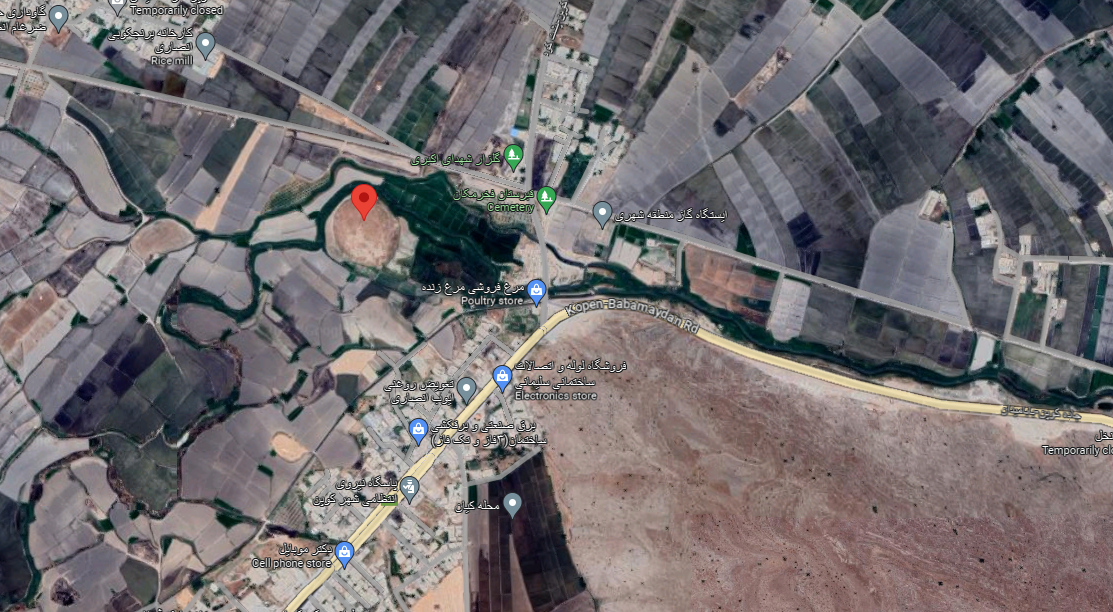

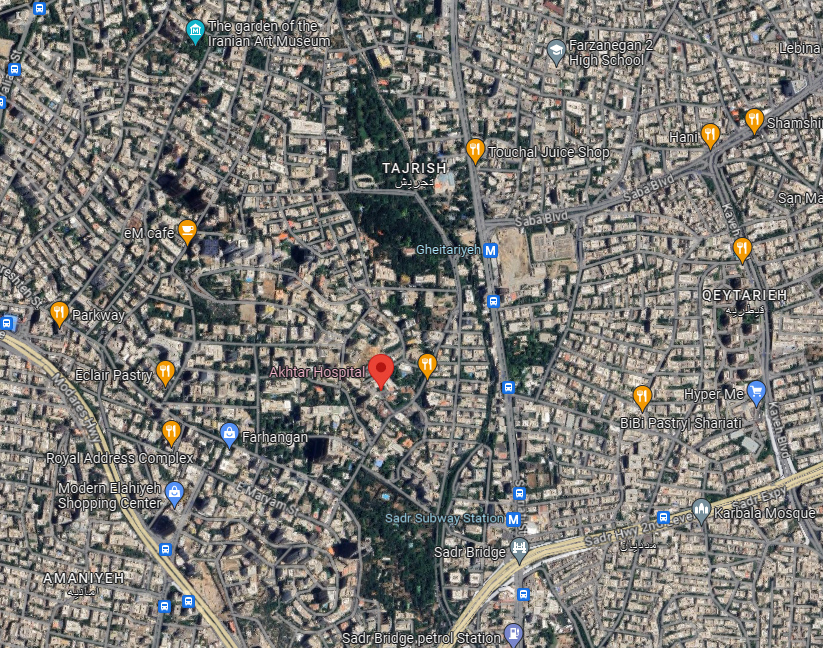

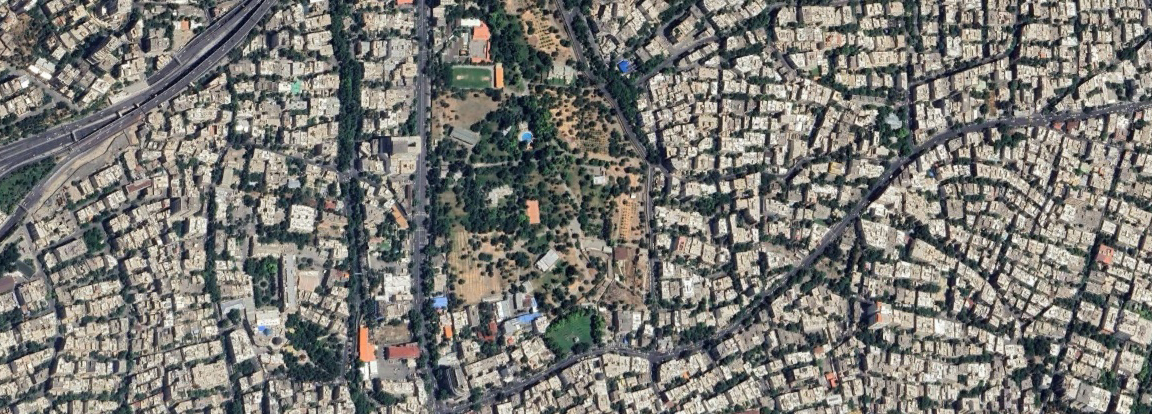

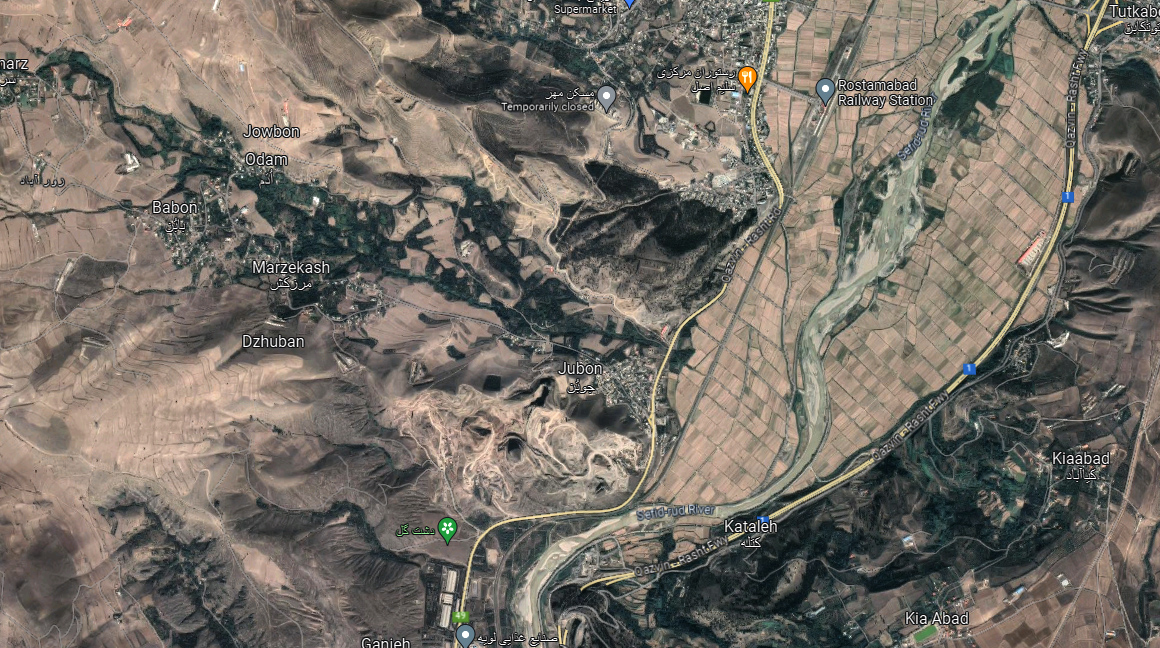

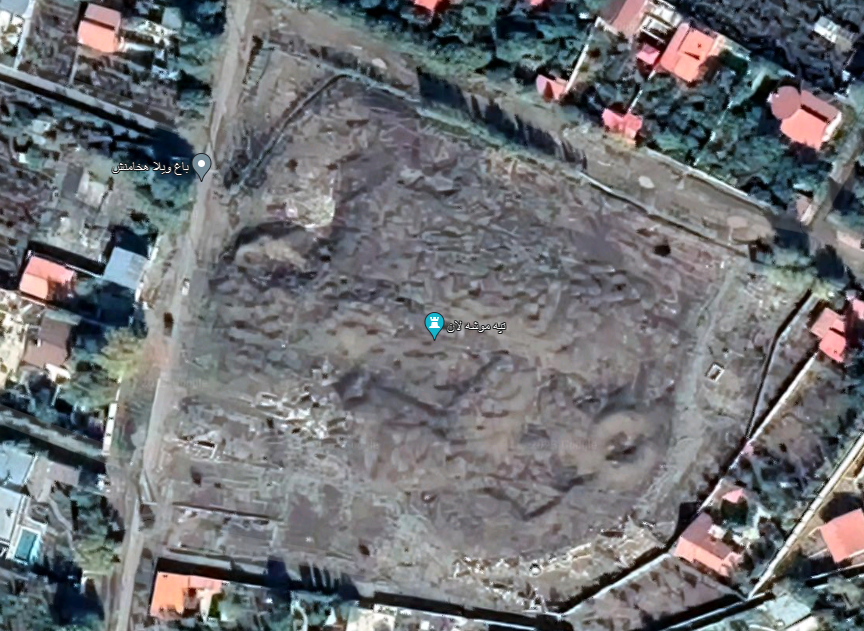

Location: Gelālak is a locality 3 km south of Shushtar, southwestern Iran, Khuzestan Province.

32° 0’21.21″N 48°49’43.73″E

Location:

History and Description:

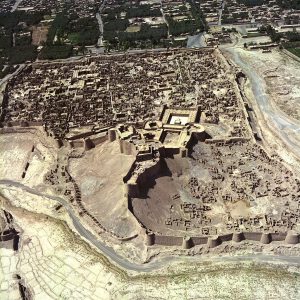

Shushtar enjoys a favorable location on the Karun River. To the north of the town, the river splits into two branches, the Shōteyteh and the Gargar, which join together 40 km downstream. The area formed by such a river bifurcation is called Miyān-Āb (between the waters), creating an extremely fertile land equipped with a considerable system of irrigation canals and waterworks. As early as the first century B.C., the region attracted the Parthians and Elymaeans. The town of Dastowā, situated 3 km south of Shushtar, was established during this period. Its pre-Islamic name remains unknown. The earliest recorded mention of Dastowā appears in the twelfth-century work Kitab al-Ansāb by Abu Sa’d Sam’āni. During this time, the Elymaean princes relocated their capital from Izeh to the area south of Shushtar, near the Gargar River. Later, Dastowā was destroyed by floods, prompting its inhabitants to move northward to what is now Shushtar. Under Parthian rule, the dynastic system of the Elymaeans was altered, with Parthian princes replacing local rulers. Despite this change, the new rulers retained the title of Kamnashkir.

Archaeological Exploration:

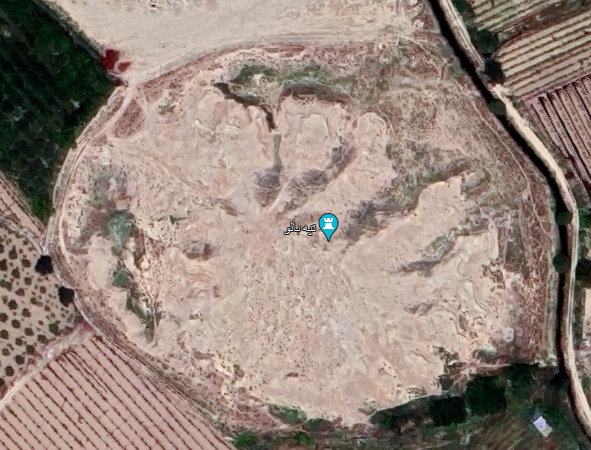

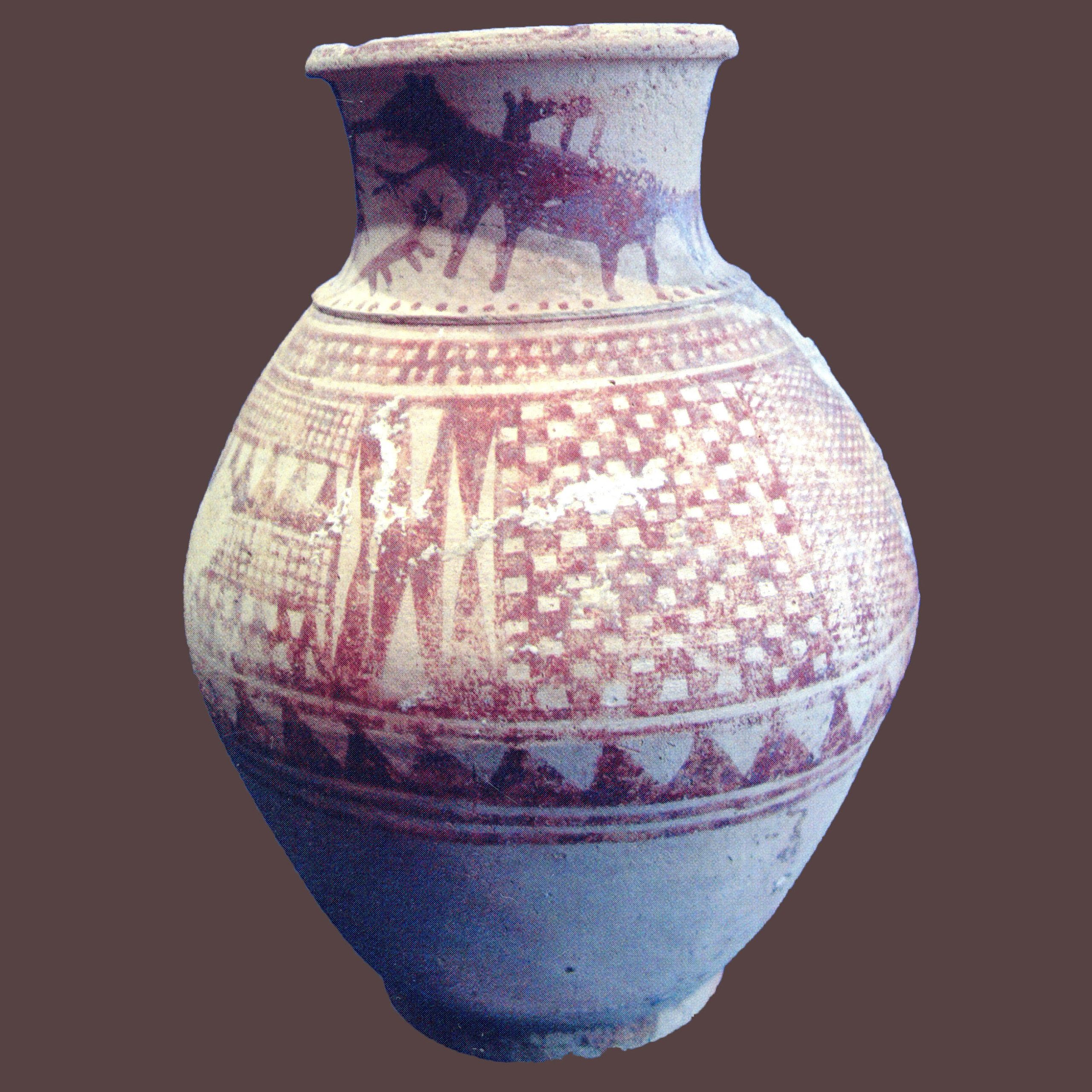

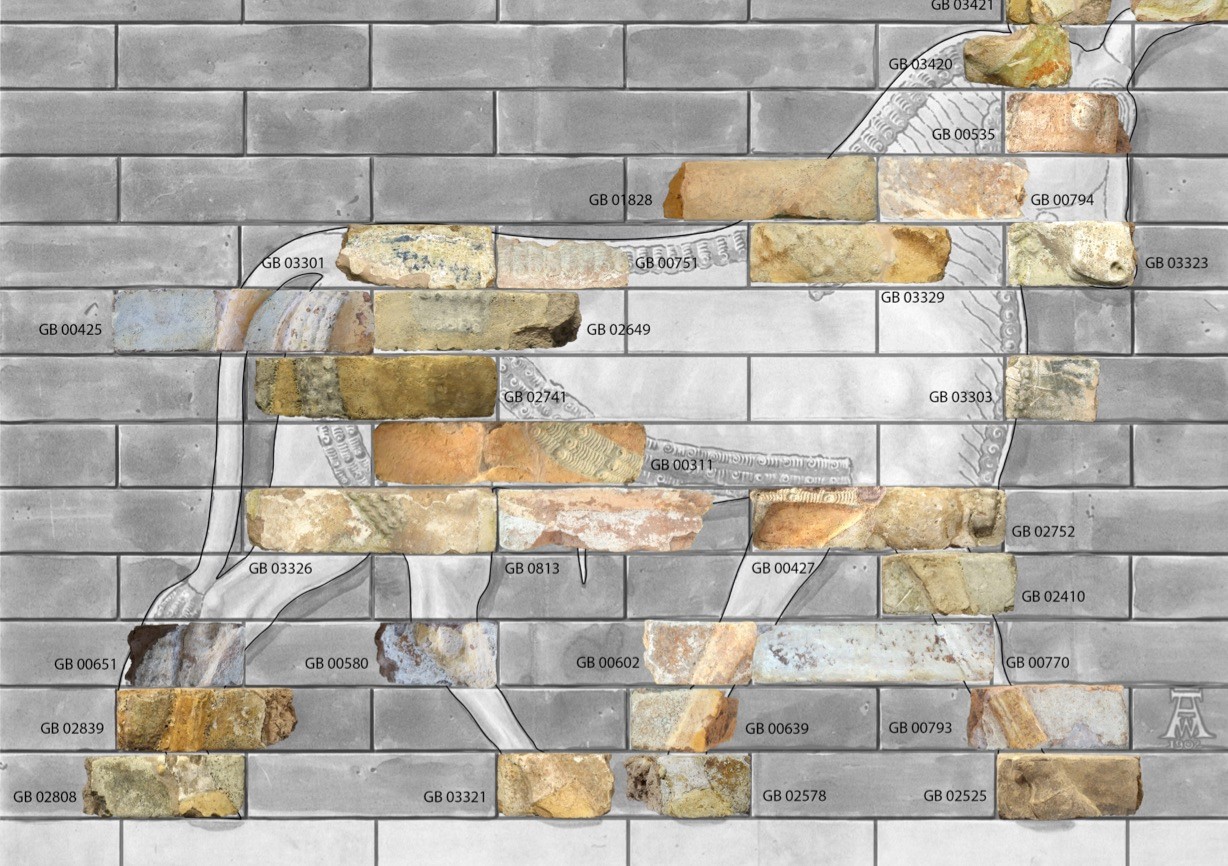

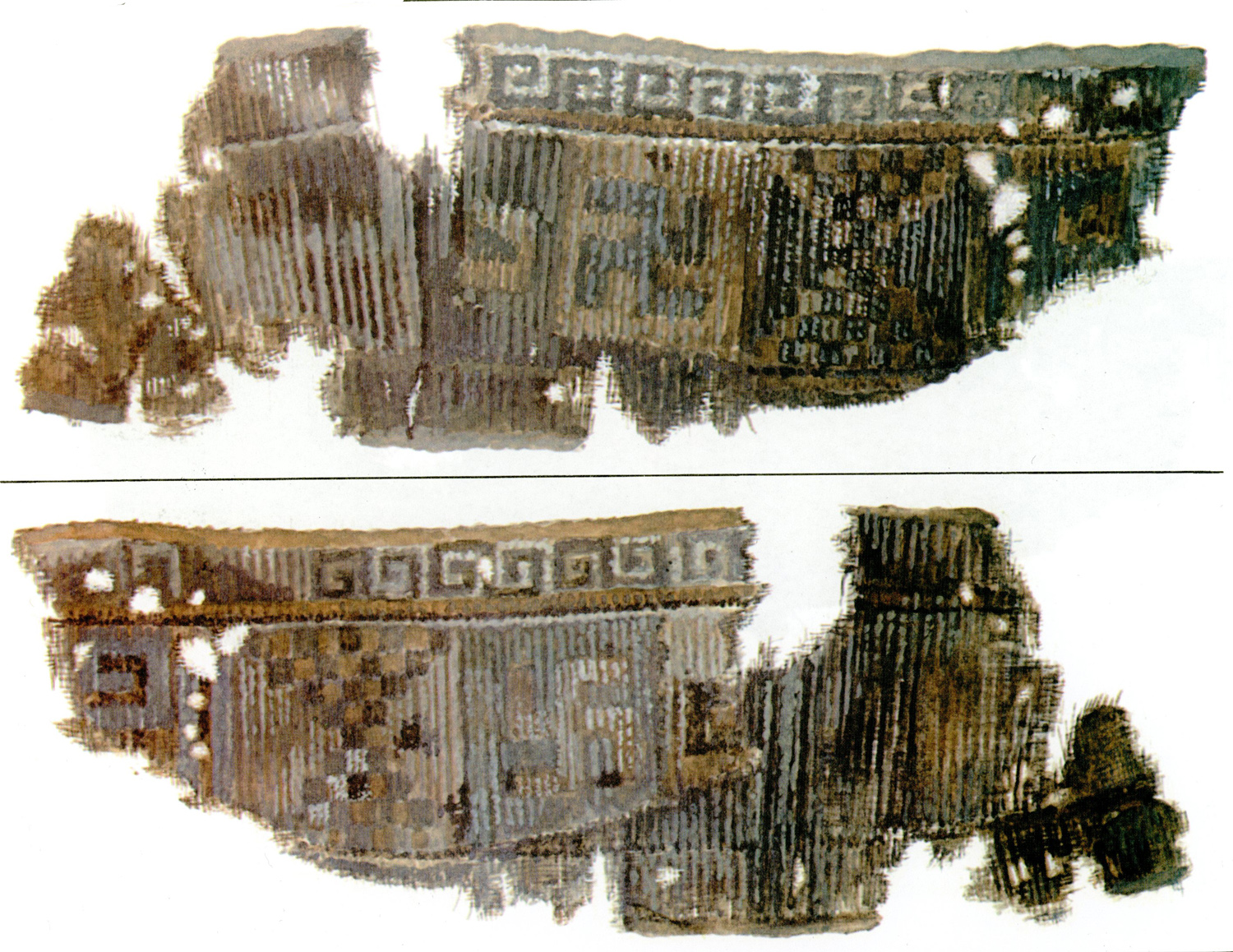

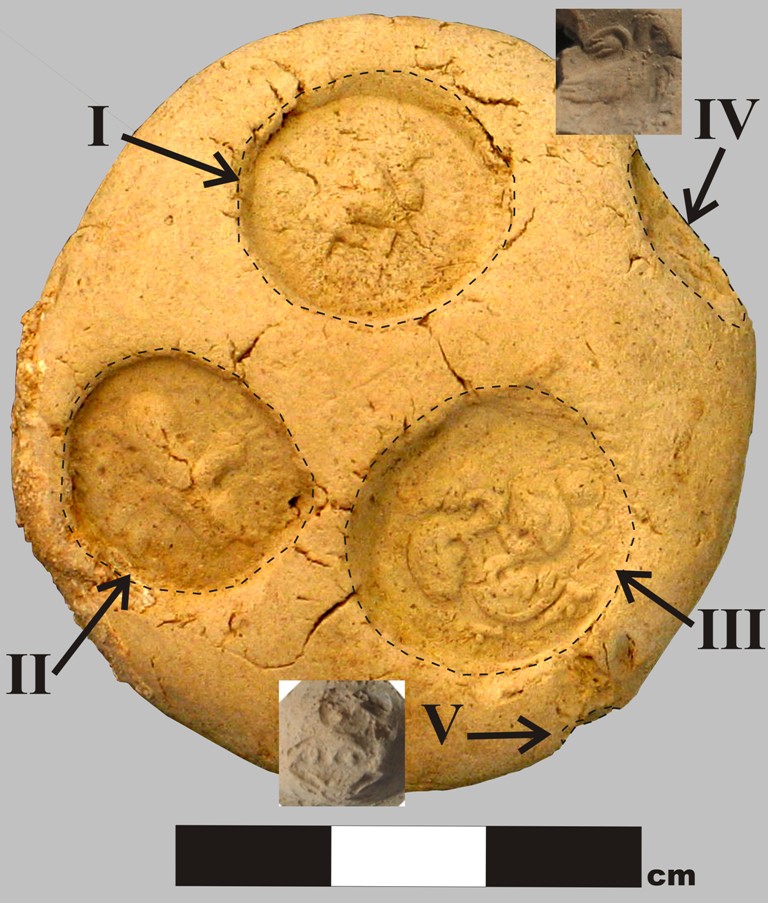

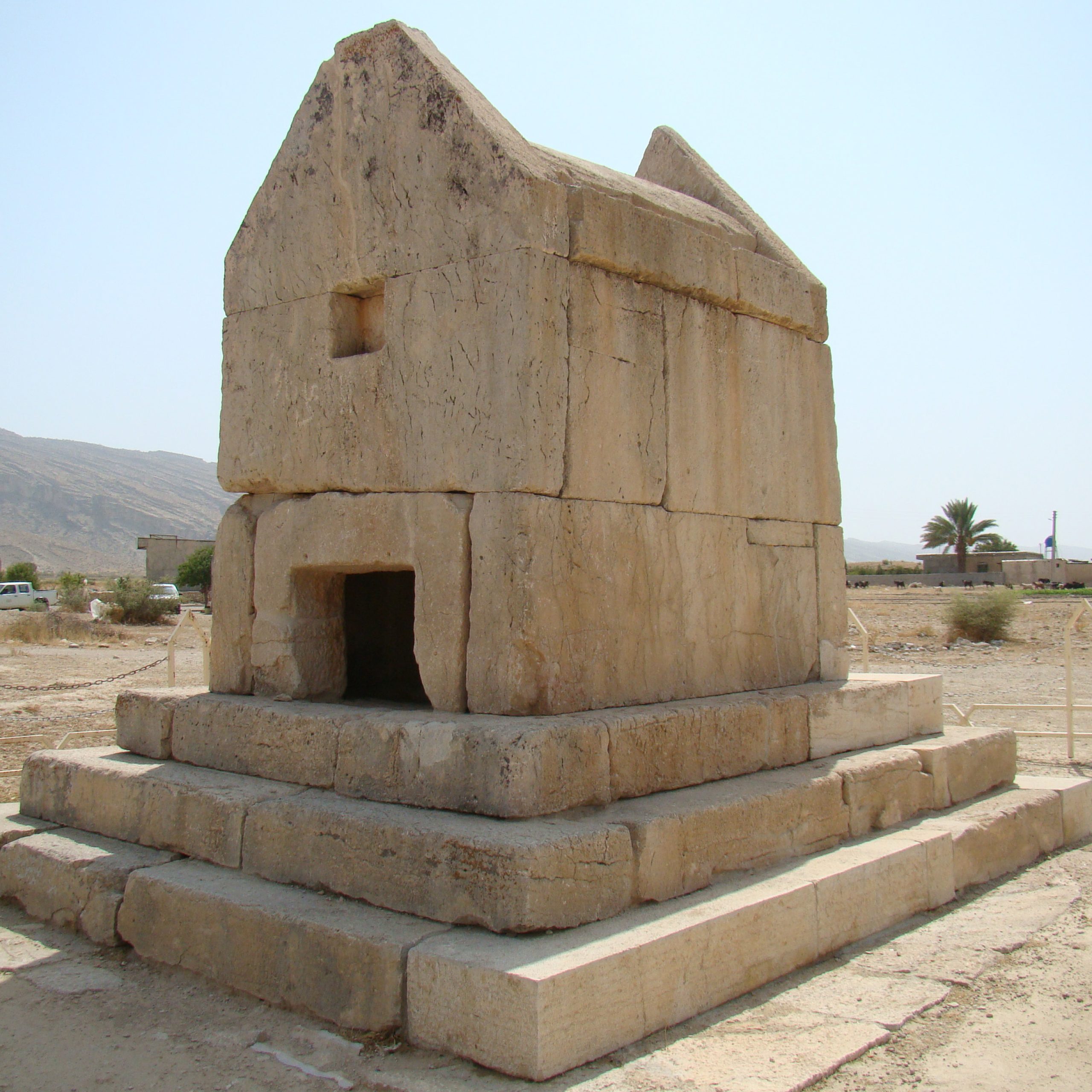

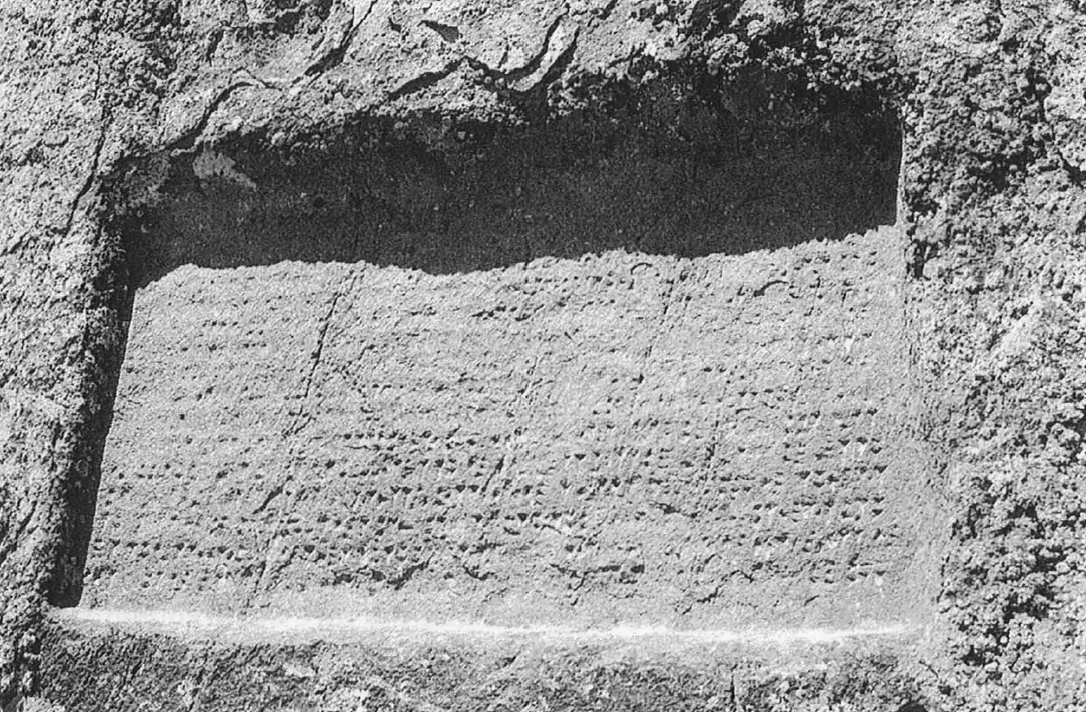

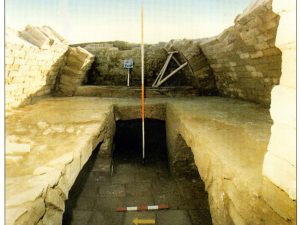

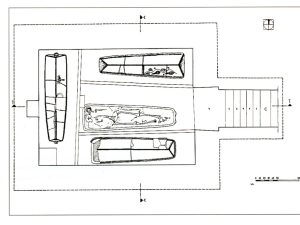

Ali Akbar Sarfaraz was the first archaeologist to conduct a survey and limited soundings in the area on behalf of the Iranian Archaeological Department in 1347/1968. Sarfaraz opened two trenches (named A and B in his report). His excavations yielded a fifth-century Sasanian layer of occupation dated with a lead coin of Peroz (457-483), an Elymaean tomb built in burnt bricks and a glazed, terracotta coffin, copper coins, and potsherds. In another sounding close to the Mahibāzān area, a pottery kiln of late Sasanian period was discovered (“Shahr-e tārikhi-ye Dastowā,”). Mehdi Rahbar of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research carried out three seasons of excavations at Gelālak, in the whereabouts of Dastowā, south of Shushtar, in the years 1365/1986-87, 1366/1987-88, and 1369/1989-90 (Rahbar, “Les tombeaux d’époque parthe de Gelālak,”; “Kavosh-e bāstānshenāsi dar Gelālak, Shushtar,”). Rahbar uncovered five subterranean and semi-subterranean tombs, two pottery kilns, an unknown structure in stone, and two structures in mud-brick at Gelālak, of which he has so far published the tombs (fig. 1, fig. 2, fig. 3). The architecture of the tombs is homogeneous in that all of them are semi-subterranean built structures in burnt bricks bound together with white mortar. A staircase leads to the underground, often vaulted chamber in which are placed two to three terracotta coffins or sarcophagi containing skeletal remains and grave goods. The size of the tomb chambers varies little; they are often in the range of 4 x 3 x 2 m. Staircases are about 2 m long. Some of them are built outside the burial chamber, and some are included inside. Inside the burial chamber are usually three raised platforms in burnt bricks, on top of which is placed a glazed, terracotta coffin; there is a niche in the lower part of the platforms possibly used for burial as well. The coffins and their lid in blue terracotta are all decorated with bas-reliefs depicting palm trees and thick necklaces with ribbons (fig. 4, fig. 5). A unique example is a fragmentary sarcophagus depicting the painted portrait of a woman with long hair (fig. 6). The gypsum bust of a divinity, (possible Anahita) was found on one of the platforms inside Tomb 1 (fig. 7). Whereas fragments of plain and glazed Parthian ceramics and vessels in glass form the majority of grave goods, the burials contained a few seals and 37 coins in copper and lead. The coins show the ruler’s effigy on the obverse with the motifs of the moon and a trident; the reverse side bears a legend in Greek or Aramean indicating the name of the king and a representation of the Elymaean goddess, Nana, the equivalent of Anahita (Curtis and Simpson, “Archaeological News from Iran: Second Report,” p. 189).

Fig. 1. General view of the subterranean tomb (tomb 1) from above (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 2. The subterranean tomb after excavation (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 3. Plan of Tomb 1 and the position of burials (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 4. Glazed terracotta sarcophagus (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 5. Glazed terracotta sarcophagus with motifs of palm trees (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 6. Fragmentary sculpture of a female figure in terracotta (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Fig. 7. Bust of a female figure or deity (photo: Mehdi Rahbar)

Finds:

Parthian terracotta and glazed coffins; the Clinky Ware, vessels in glass, gypsum bust with a human figure; terracotta rhyton. Thirty-seven bronze and lead coins were found, dating to the reign of Orodes I and Orodes II of the Elymaean dynasty of the Kamanskiris in the first and early second centuries A.D. The coins show the ruler’s effigy on the obverse with the motifs of the moon and a trident; the reverse side bears a legend in Greek or Aramean, indicating the name of the king and a representation of the Elymaean goddess, Nana, to be the equivalent of Anahita. Among the inscribed finds is a seal in stone that bear in Greek the name Orodak, a diminutive form of Orodes (published in V. Curtis and St John Simpson, “Archaeological News from Iran: second report,” p. 189).

Bibliography:

Boucharlat, R., “Some Remarks on the Monumental Parthian Tombs of Gelālak and Susa,” Afarin Nameh. Essays on the Archaeology of Iran in Honour of Mehdi Rahbar, Y. Moradi (ed.), Tehran, 2019, pp. 49-58.

Curtis, V. and St John Simpson, “Archaeological News from Iran: Second Report,” Iran 36, pp. 185-195.

Rahbar, M., “Les tombeaux d’époque parthe de Gelālak,” Dossiers d’Archéologie 23, mai 1989, pp. 90-93.

Rahbar, M., “Kavosh-e bāstānshenāsi dar Gelālak, Shushtar,” Yādnāme-ye Gerdehamāyi-e Bāstānshenāsiy-e Shush (The Memorial Volume of the Archaeological Symposium at Susa), Shush 1373, M. Mousavi (ed.), Tehran, 1376/1997, pp. 175-208.

Sarfaraz, A., “Shahr-e tārikhi-ye Dastowā,” Bastan Chenasi va Honar-e Iran 4, 1348/1969, pp. 72-79.