Maragha Observatoryرصدخانه مراغه

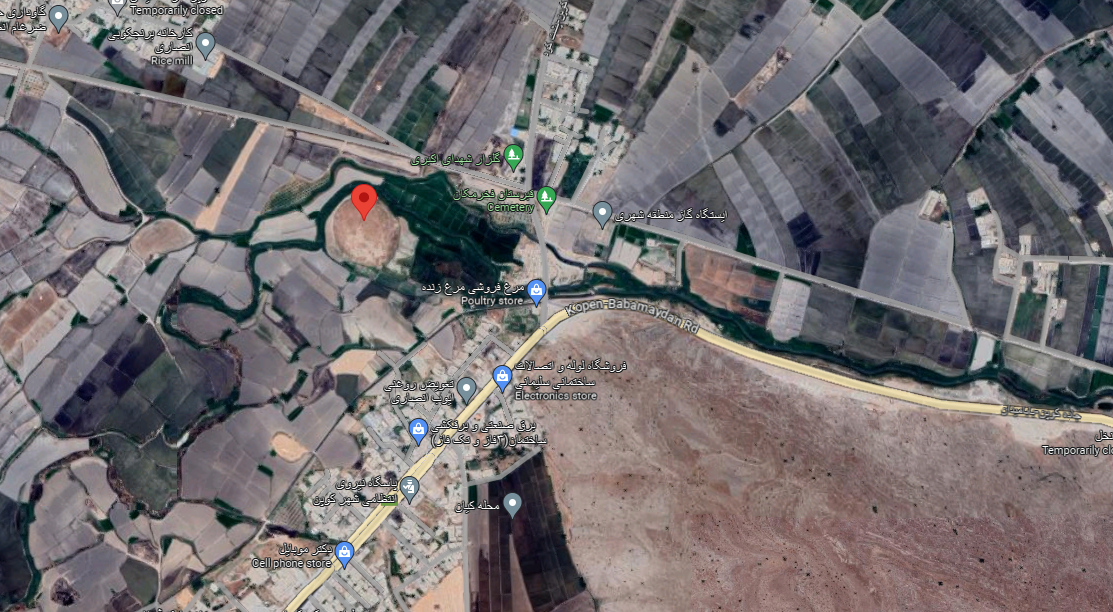

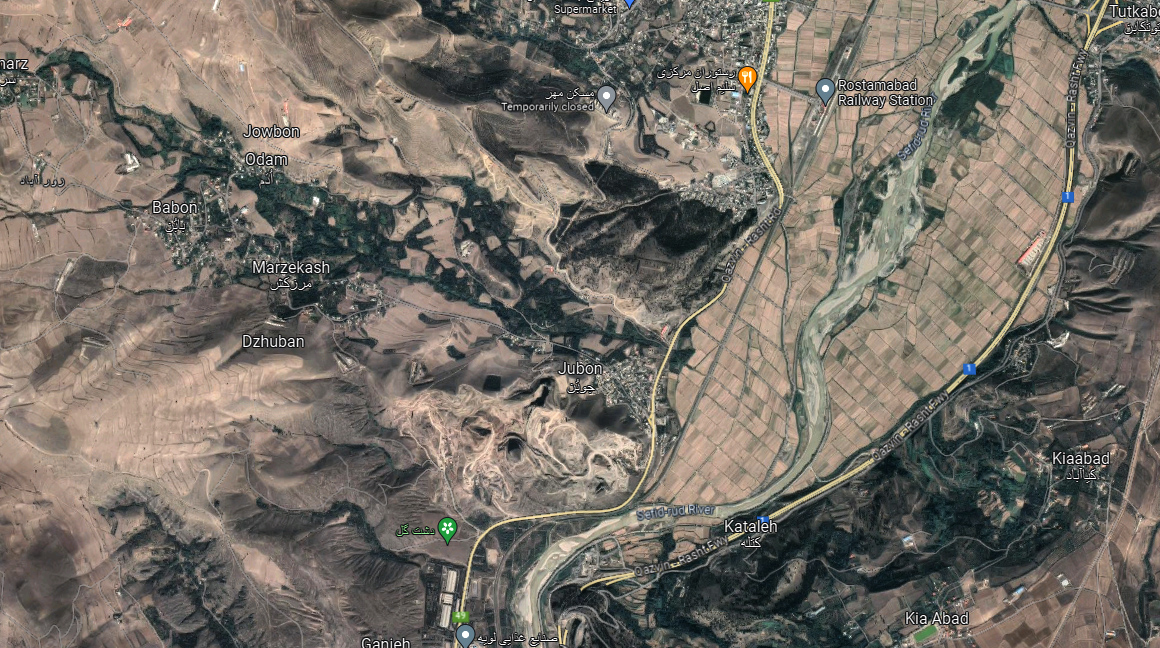

Location: The observatory is in the vicinity of Maragha in northwestern Iran, West Azarbaijan Province.

37°23’46.0″N 46°12’33.0″E

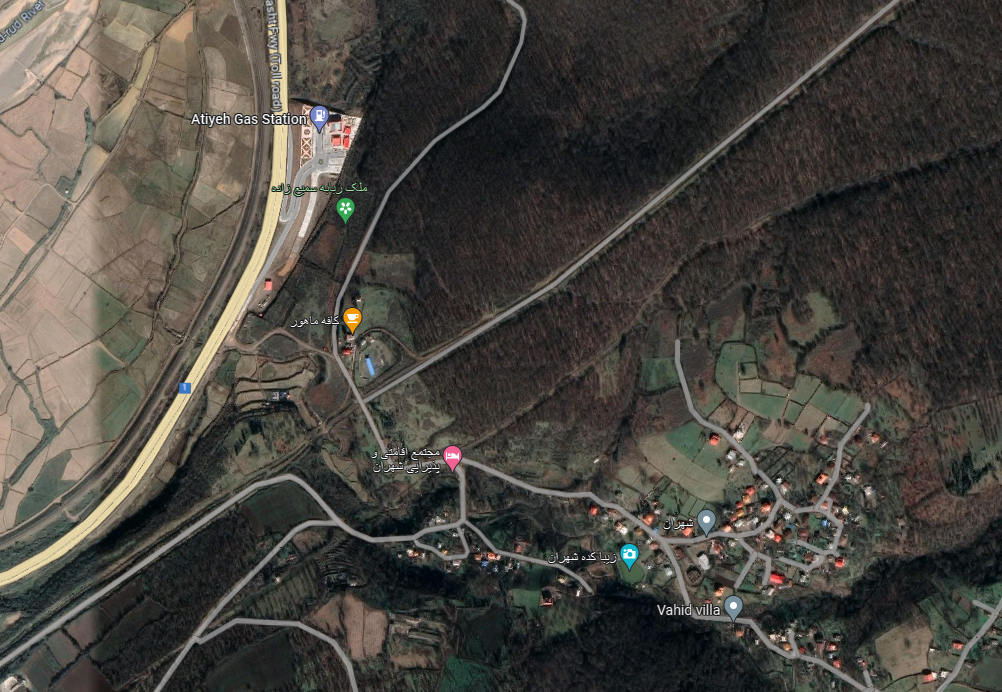

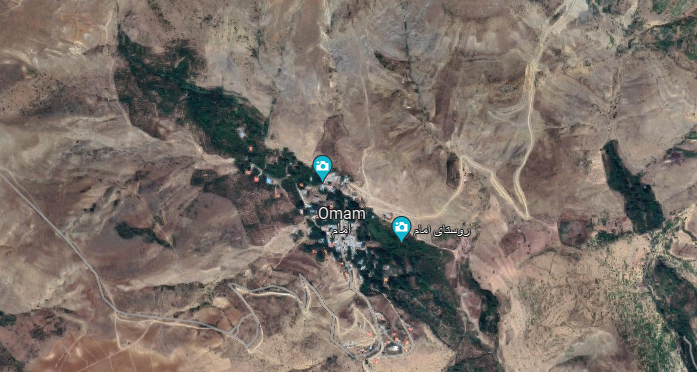

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

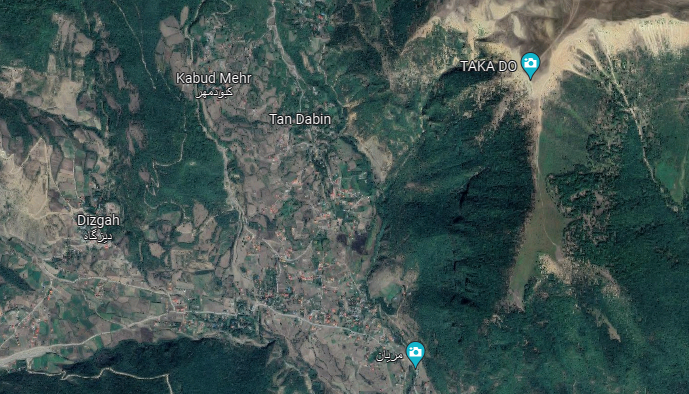

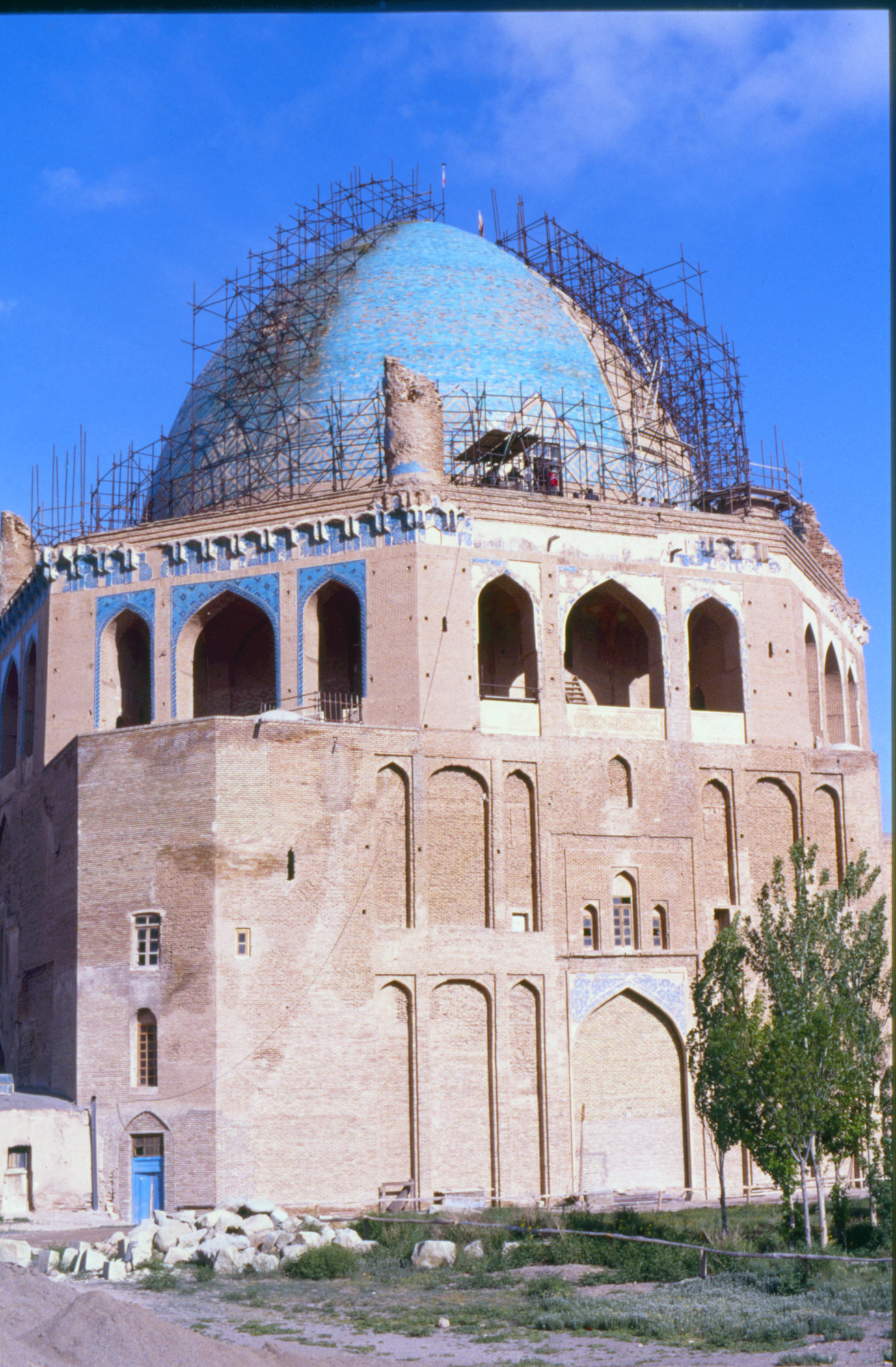

Marāgha is situated on the southern slope of Mount Sahand, 80 km south of Tabriz. The town is built on the left bank of the river Sūfi Chāy, and is well watered by several other streams. Its mild climate and geographical position near Lake Urmia made it the best choice for being an important center as early as the tenth century. On account of its abundant pastures, Marāgha was a station on the road between Azarbaijan and Mesopotamia. When Marāgha was chosen as the capital of the Ilkhāns by Hülegü in 1256, Nasir al-Din Tūsi requested substantial funding from his new patron to carry out fresh astronomical observations over a span of thirty years. Hülegü approved the proposal. Following the fall of Baghdad in 1258, Ṭusi was granted a generous endowment to establish a new observatory in Marāgha. The construction began in 657 AH /1258. A large madrasa and an important library were also built near the observatory, which reportedly contained 400,000 manuscripts. Despite Hülegü’s eagerness, the scientific work of the observatory lasted nearly fifteen years, and the results of the research were not published until the reign of Abāqā Khān in 663 AH / 1265, in the book titled Zīj-i Īlkhānī, which was later translated into Latin and published in Europe as early as 1652. The observatory’s main complex was built by two architects or builders: Fakhr al-Din Ahmad Amin Maraghi and Mo’ayed al-Din Orzi.

The observatory is mentioned in two contemporary sources: Fawat –al Vafiyāt by Muhammad ibn Shakir ibn Ahmad al-Kōtōbi, the Arab historian of the early fourteenth century, and in Tarikh-e Wassaf by Sharaf al-Din Shīrāzī known as Wassaf, a native of Shiraz, panegyrist and tax administrator in the court of the Ilkhāns.

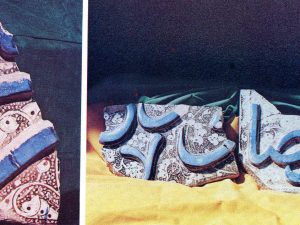

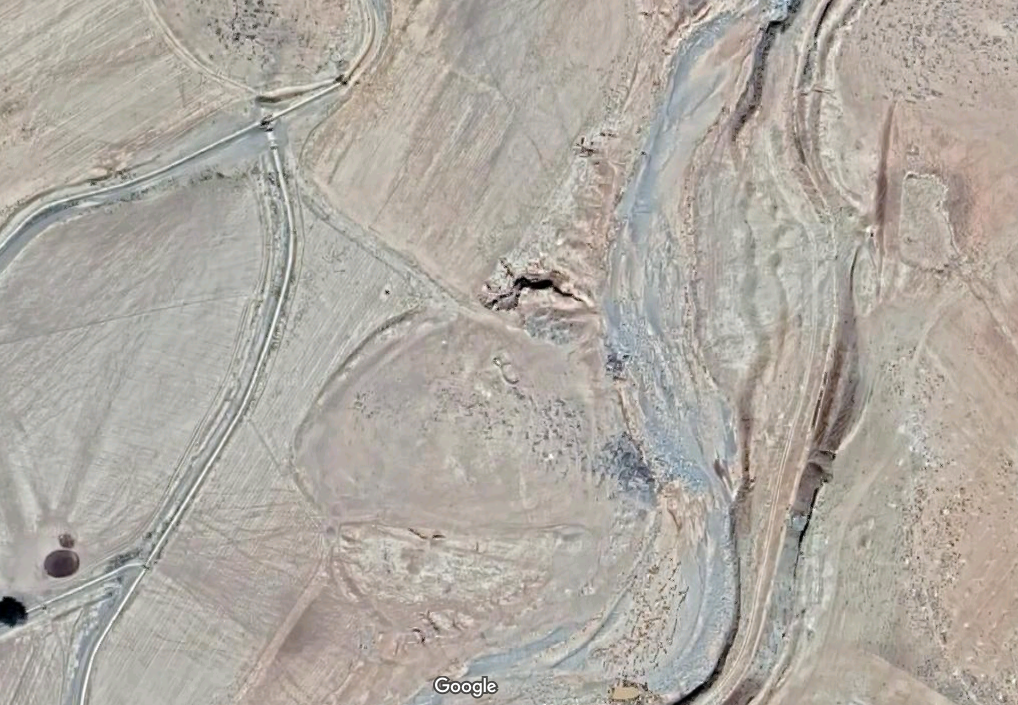

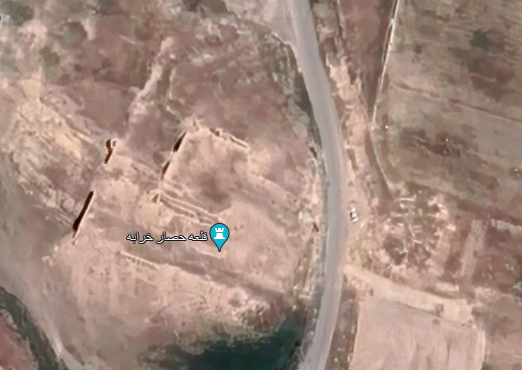

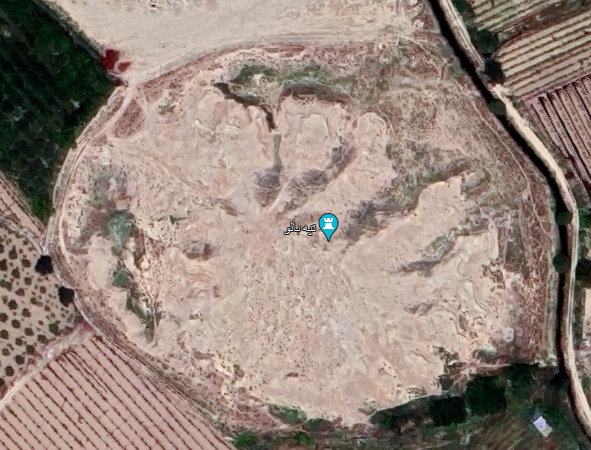

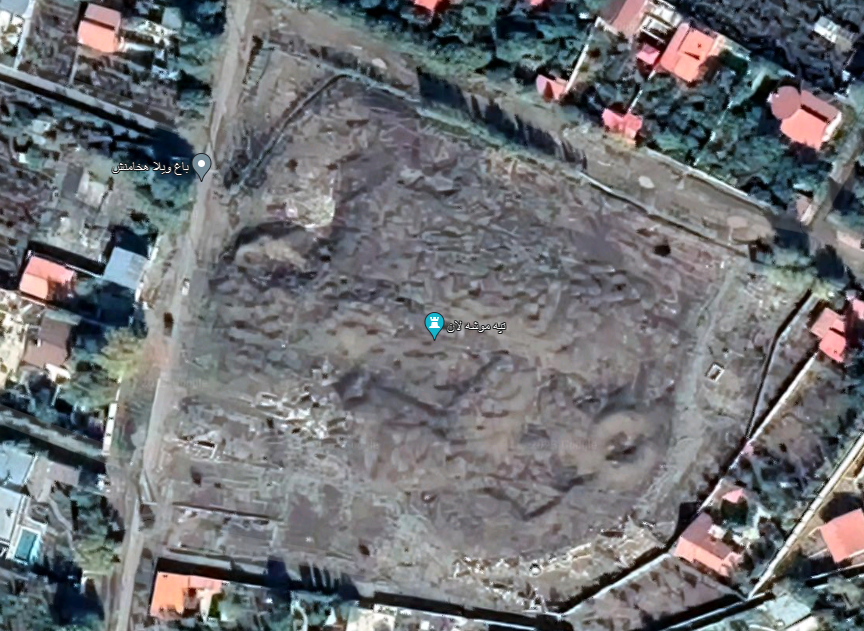

Rasad Dāghi, also known as Observatory Mount, is a natural hill composed of horizontally layered sandstone that was leveled by removing the basalt stones that lay on its surface. The extracted stones were then used as the foundation for the walls. The natural hill is in the form of a tongue with a pointed north edge and a southern flat edge. Its maximum length is 500 m, and its width varies between 212 and 45 m. Its height is approximately 32 m above the surrounding fields.

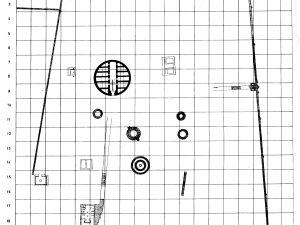

Construction began in 657 H/1259 atop a natural hill measuring 530 by 260 meters. The excavated remains consist of two enclosure walls (fig. 1): a north-south wall measuring 197 by 1.2 meters, and an east-west wall measuring 139 by 1 meter. In the southern sector, 17 structures have been identified, including astronomical installations, a metalsmith’s casting workshop, a pavilion, a madrasa complete with a library and classrooms, and a water reservoir.

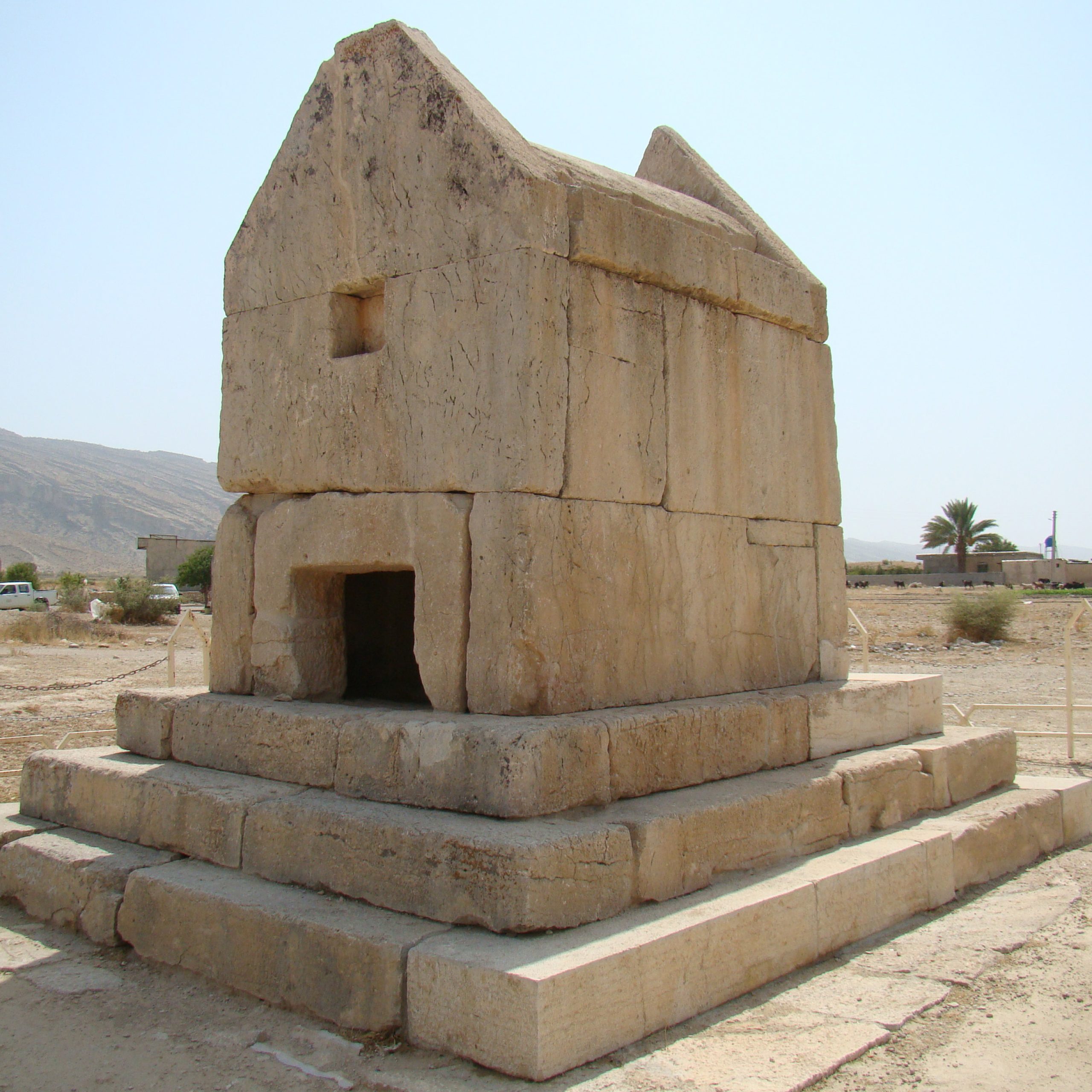

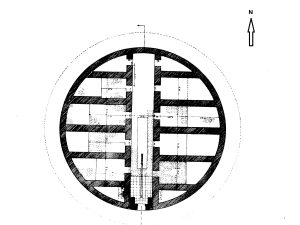

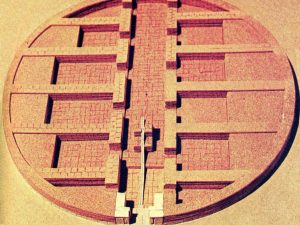

The central tower (figs. 2 and 3): The layout of the structure is based on perfect concentric circles. From the outside in, one first sees a circle with a radius of one meter that marks the foundation of the monument. The main entrance faced south. Upon passing through it, one descended between two small stone platforms, each 0.80 meters high, and then down two steps, measuring 0.13 and 0.14 meters high respectively. This led into the main stone hall of the building (22 x 3.10 meters), shaped like a long corridor aligned along the north-south diameter of the observatory.

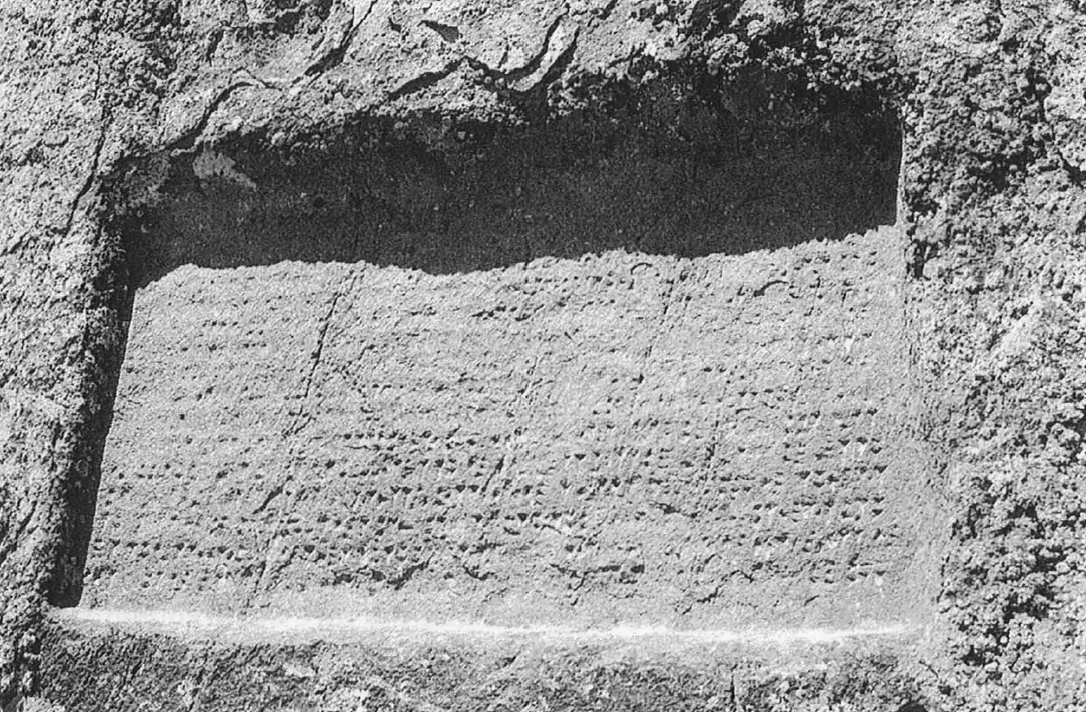

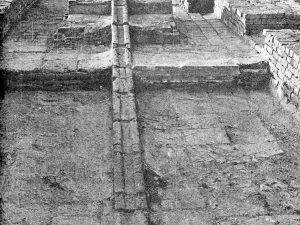

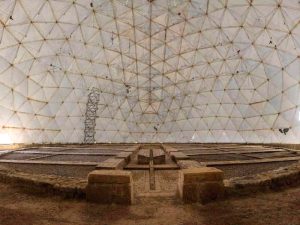

In this corridor-hall, directly opposite the entrance, stood the base of the sighting instrument and mural quadrant (figs. 4 and 5). Originally, it was a staircase measuring 7.50 x 1.40 meters at the base. Now, only 2.20 meters remain, comprising three steps, each 0.23 meters high. This staircase supported the mural quadrant—a segment of an ellipse whose lowest point was near the door and whose highest point was at the center of the monument. It was built using blocks of cut stone.

In comparison to the structure’s original mass, only a small fraction of materials remains. The near-total absence of flooring—even in rooms long buried beneath layers of earth—strongly indicates that the observatory did not succumb to natural decay alone. Rather, the evidence suggests a deliberate dismantling, either swift or systematic, carried out by local people for salvaging and reusing the construction materials after the site's abandonment. At all events, the life of the observatory did not seem to last even a hundred years. Hamdullah Mostowfi, the writer and geographer in the service of the Ilkhans, who compiled his Nuzhat-al-Qolūb in A.D. 1340, mentioned that the observatory was in ruins.

Additionally, five circular traces have been excavated and are now visible to the south, southeast, and north of the central tower. Built in stone, these roofless structures likely served as platforms for placing observatory instruments.

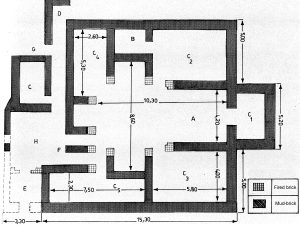

The library (fig. 6): The building located at the northwest corner of the site has been identified as the observatory’s library. Built in rubble masonry with a stone foundation, it has a surface area of 330 m² and includes 9 rooms of different sizes. The layout is cruciform, around which five rooms are arranged. In the middle of the eastern side of the building and extending outward, there is a chamber (3.30 x 2.20 m) that connects to the main room. The entrance, shaped like a corridor, is located at the northwest corner. The situation at the southwest corner is not very clear, but it can be assumed that there was once an entrance or exit there, allowing people to enter the building through one door and exit through another.

Considering its layout, the crenelated niches, the well-monitored entrance and exit, and finally the square enclosure that separates this building from the rest of the observatory complex, the structure may have served as the observatory’s famous library. Some sources indicate that around 400,000 volumes were kept in the library of the Marāgha Observatory—an exaggerated number that does not correspond realistically with the building’s capacity. However, in any case, among the excavated, this is the only one that could have served as a library.

A pavilion was built to the east of the central tower, which seems to be the reception hall constructed by Orzi for the Ilkhān Hülegü. The observatory was equipped with a water reservoir, the remains of which were found on the south slope of the hill. Besides, a series of rock-cut rooms with arched entrances is located on the west slope of the hill. As for their debated function, Parviz Varjavand, the excavator of the site, believes that they served as auxiliary rooms to accommodate lectures and meetings.

Fig. 1. The plan of the excavated remains of the Maragha Observatory (after Varjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha)

Fig. 2. The central tower of the Maragha Observatory (after Varjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha)

Fig. 3. The model of the central tower of the Maragha Observatory (after Varjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha)

Fig. 4. The mural quadrant in the central tower of the Maragha Observatory after excavation (after Varjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha)

Fig. 5. The mural quadrant in the central tower of the Maragha Observatory with the protective roof (image: A. Afrouzi)

Fig. 6. The plan of the library in the Maragha Observatory (after Varjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha)

Archaeological Exploration

Some of the observatory’s remains were still visible as late as 805 H/1402 when Ghiyath al-Din Kashani, the Persian astronomer and mathematician in the service of the Timurid ruler Shah Rokh and later his son, Ulūgh Beg, visited the site and recorded his observations.

For two hundred years, there was very little information on the state of preservation of the ruined observatory until the Safavid period. After the capture of the castle of Dim Dim (on the west shore of Lake Urmia) in 1019 H/1610 AD, Shah Abbas I dispatched a mission to explore and draft a plan of the Marāgha observatory.

During the Qajar period, there is a report from the reign of Nāser al-Din Shāh Qājār and is dated to the year 1276 AH (1859 AD), when the king visited Marāgha during his journey to Azarbaijan. Prince Aligholi Mirzā Eʿtezād al-Saltana, who was accompanying the Shah, had a deep interest in astronomy and the celestial sciences. Along with Prince Farhād Mīrzā, Mullā Ali-Muḥammad of Isfahan, a famous mathematician of the era, and Mīrzā Ahmad, the royal physician from Kashan, they visited the ruins of the observatory.

Eʿtezād al-Saltana wrote a detailed account of their observations and findings. Fortunately, a copy of this report, which had been prepared for the royal library of Nāser al-Dīn Shāh, has survived as a manuscript in the Royal Library and is now preserved in the National Library of Iran. One of the valuable features of this treatise is a drawing of the layout of the hill on which the observatory stood. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that Eʿtezād al-Saltaneh published a summary of this treatise in the seventh issue of the newspaper ʿIlmīya-ye Īrān.

In 1882, Albert Houtum-Schindler, the German engineer in charge of laying telegraph wires in Persia, visited the site of the observatory and drew a sketch plan of the remains.

The observatory’s remains were detected by Parviz Varjavand, archaeologist and Professor of the University of Tehran, in the western outskirts of Marāgha, on a circular mound with a diameter of about 45 meters and a height of 2.5 meters. During the summer of 1972, Varjavand began excavations sponsored by the Ministry of Culture and Arts, the University of Tehran, and Tabriz University. Two more excavation campaigns were carried out in 1975 and 1976.

Finds

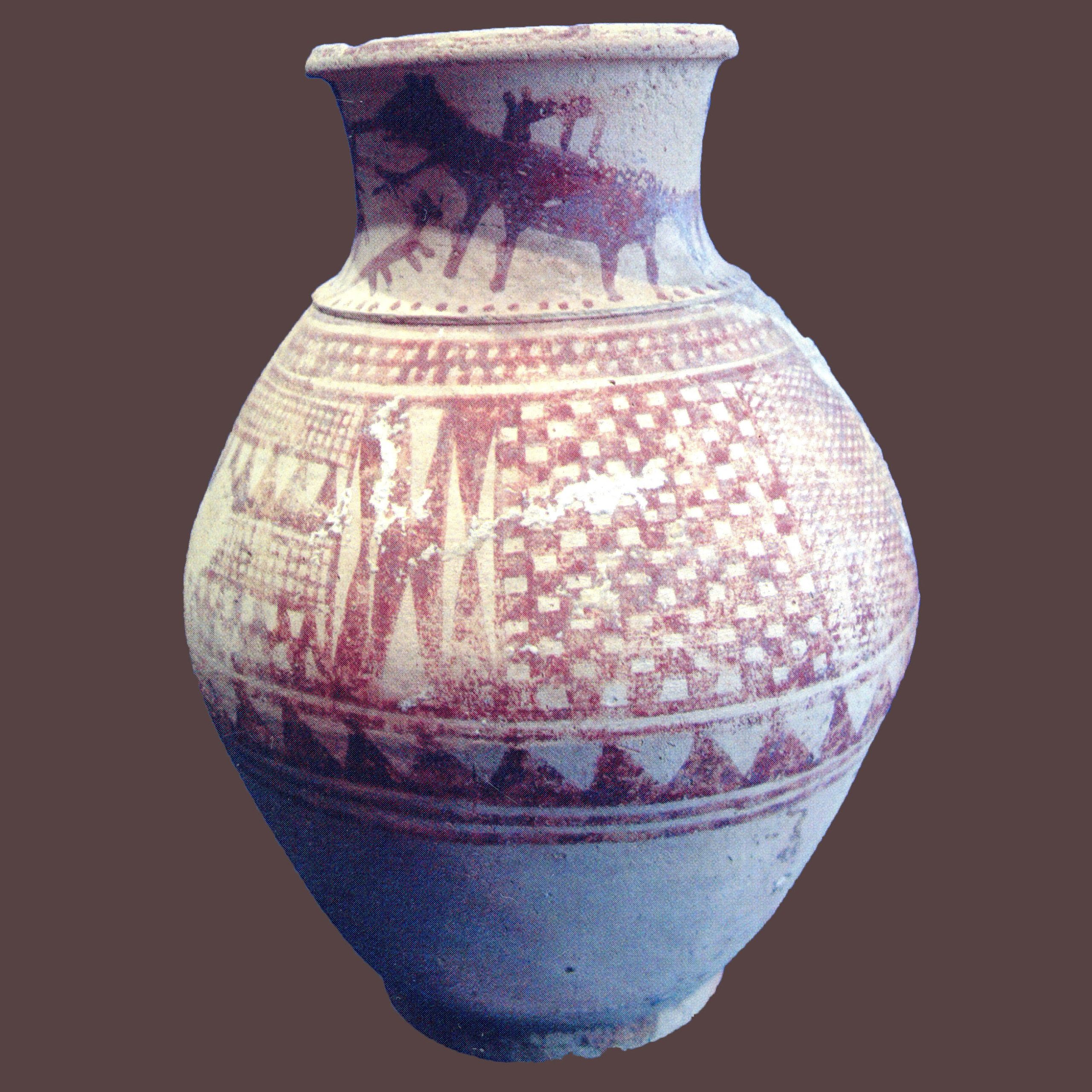

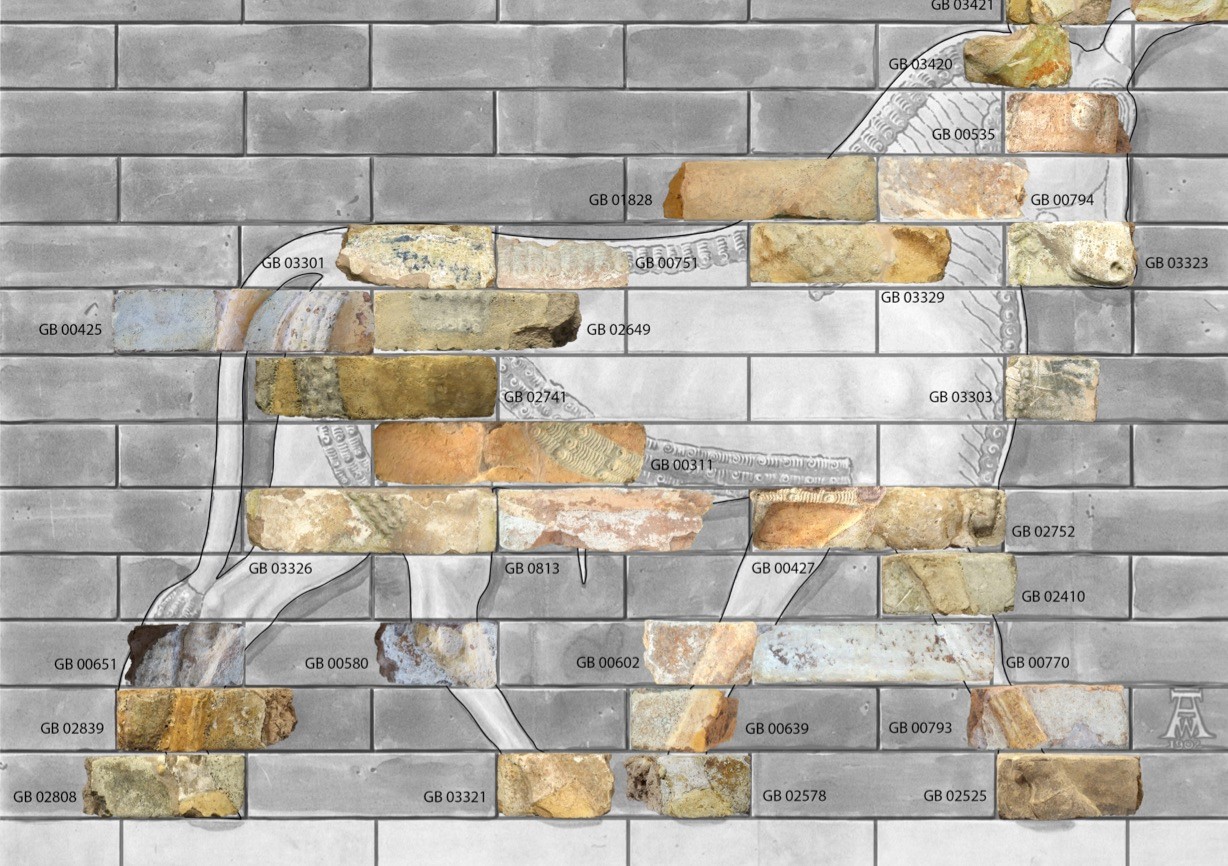

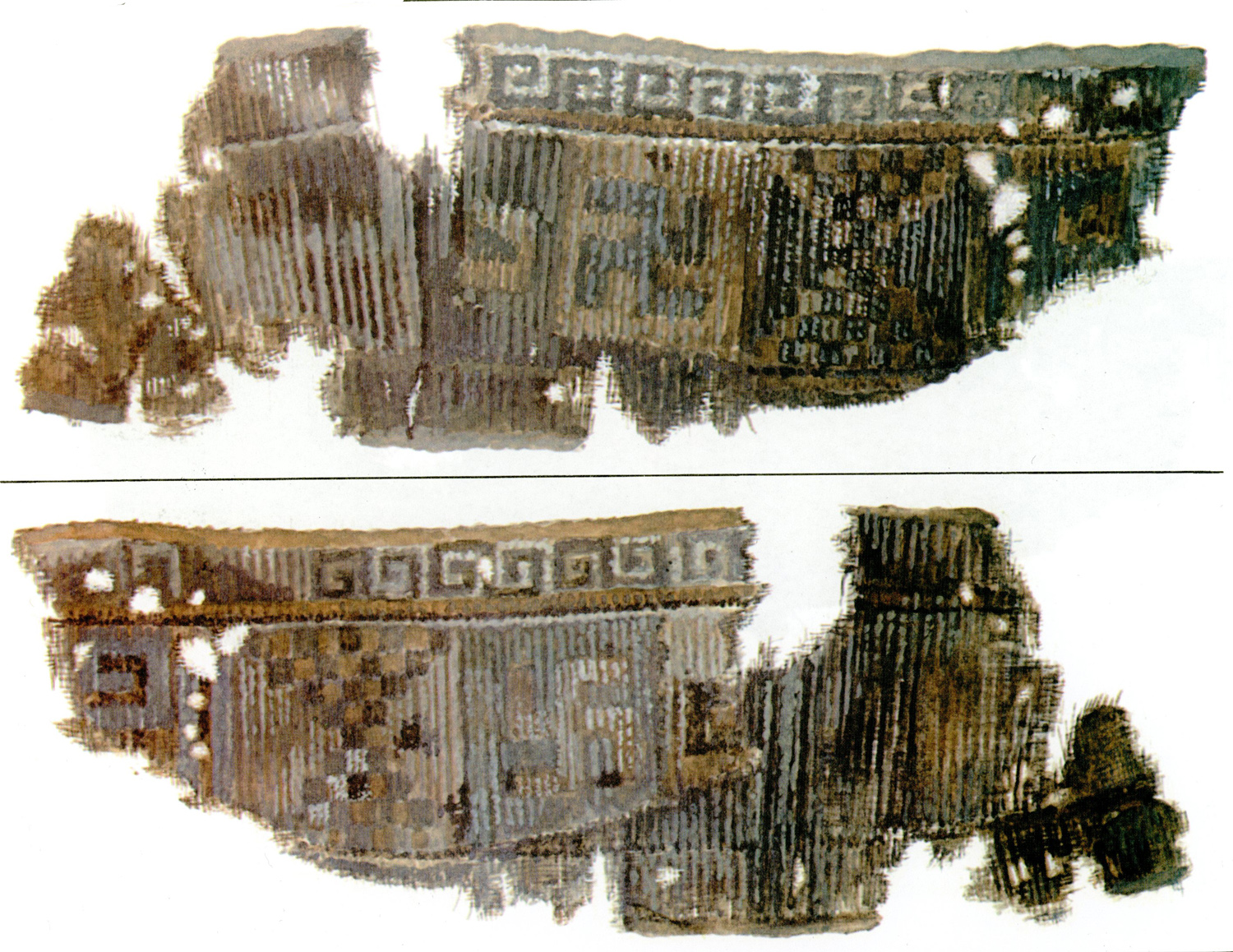

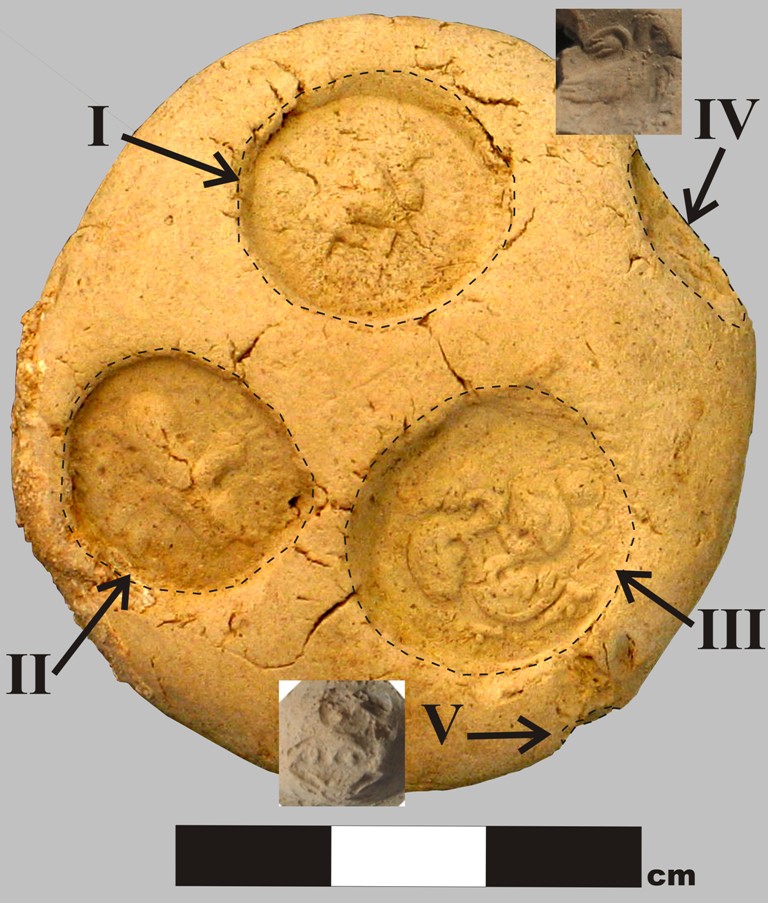

The excavated finds mainly consist of molded bricks (fig. 7), glazed tiles that once decorated the observatory’s buildings (fig. 8), plain pottery with impressions, fragments of glass vessels, sixteen eroded copper coins of the Ilkhānid period, and one Byzantine gold coin with the name and effigy of Michael V (r. 1071-1078).

Bibliography

Houtum-Schindler, A., “Reisen im nordwestlichen Persien 1880-82,” Gesellschaft für Erdkunde. Zeitschrift, Berlin, 1883, vol. 18, p. 328.

Kennedy, E. S., “A Letter of Jamshid al-Kāshi to His Father: Scientific Research and Personalities at a Fifteenth Century Court,” Orientalia, vol. 29, No. 2, 1960, pp. 191-213.

Minorsky, V., “Marāgha,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. 6, 2nd edition, Leiden, 1991, p. 501.

Mostowfi Qazvini, Hamdullah, The Geographical Part of the Nuzat-al-Qulūb, translated by G. Le Strange, London, 1919, p. 88.

Saliba,G., “Ṭusi, Nasir-al-Din ii. As Mathematician and Astronomer,” Encyclopedia Iranica Online, https://doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_981

Saliba, G., “The Role of Marāgha Observatory in the Development of Islamic Astronomy: a Scientific Revolution before the Renaissance,” Revue de Synthèse, vol. 108, 1987, pp. 361-73.

Sayili, A., “Khwajeh Nasir -al Din Tusi va rasadkhāne-ye Marāgha,” Majalle-ye Daneshkade-ye Adabiyat, vol. 3, No. 4, 1335/1956, pp. 58-72.

Sayili, A., The Observatory in Islam and Its Place in the General History of the Observatory, Ankara, 1960, pp. 189-223.

Vardjavand, P., “Rapport préliminaire sur les fouilles de l’observatoire de Marâqé,” Le Monde iranian et l’Islam, vol. 3, 1975, pp. 119-124.

Vardjavand, P., “Kashf-e majmū’e-ye elmi-ye rasadkhāne-ye Marāgha,” Honar va Mardom, No. 181, 1354/1976, pp. 2-15.

Vardjavand, P., “La découverte archéologique du complexe scientifique de l’observatoire de Maraqé,” in Akten des VII. internationalen Kongresses für iranische Kunst und Archäologie, München, 7.–10. September 1976, Berlin, 1979, pp. 527-536.

Vardjavand, P., Kavosh-e Rasadkhāneh-ye Marāgha, Tehran, 1366/1987.

Wilber, D. N., The Architecture of Islamic Iran. The Il Khānid Period, Westport, Connecticut, 1955, pp. 107-108.