Rōbāt Sharafرباط شرف

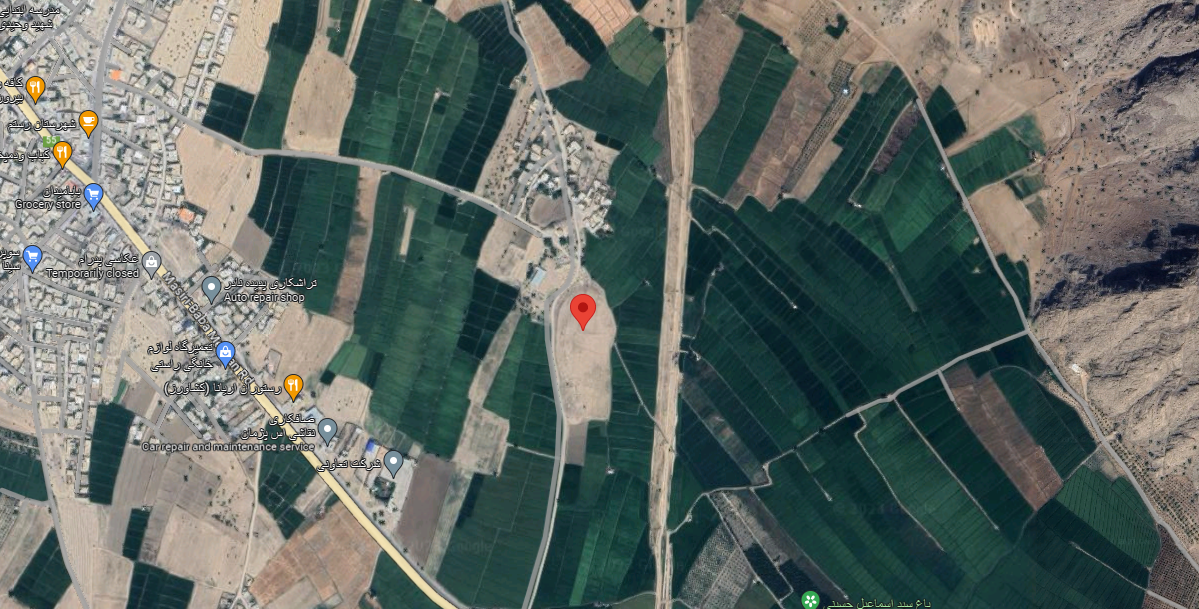

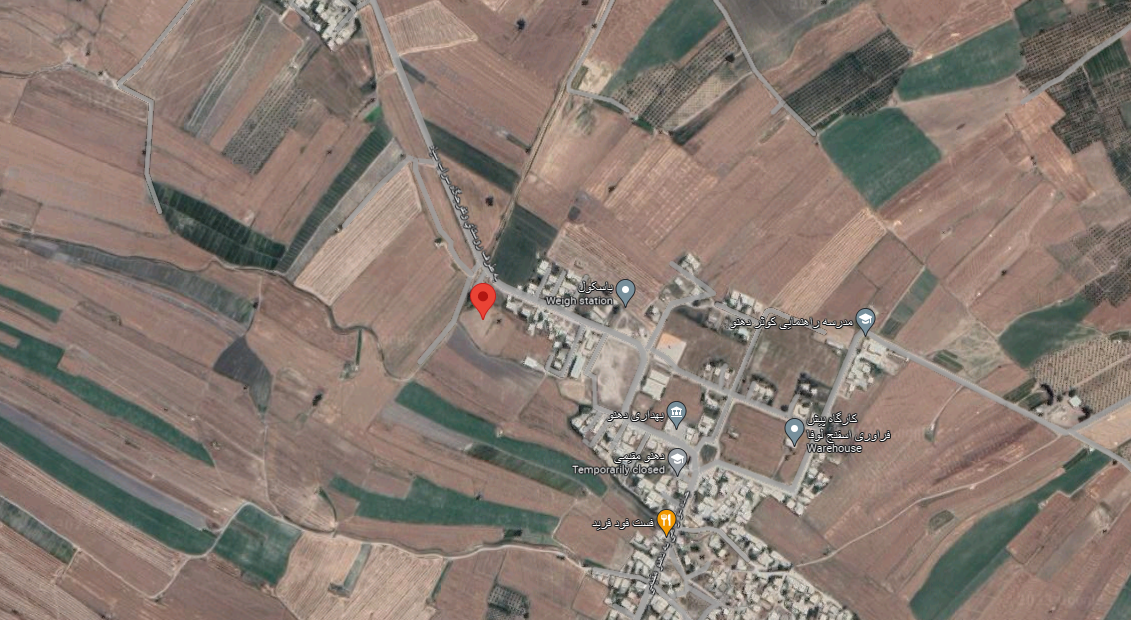

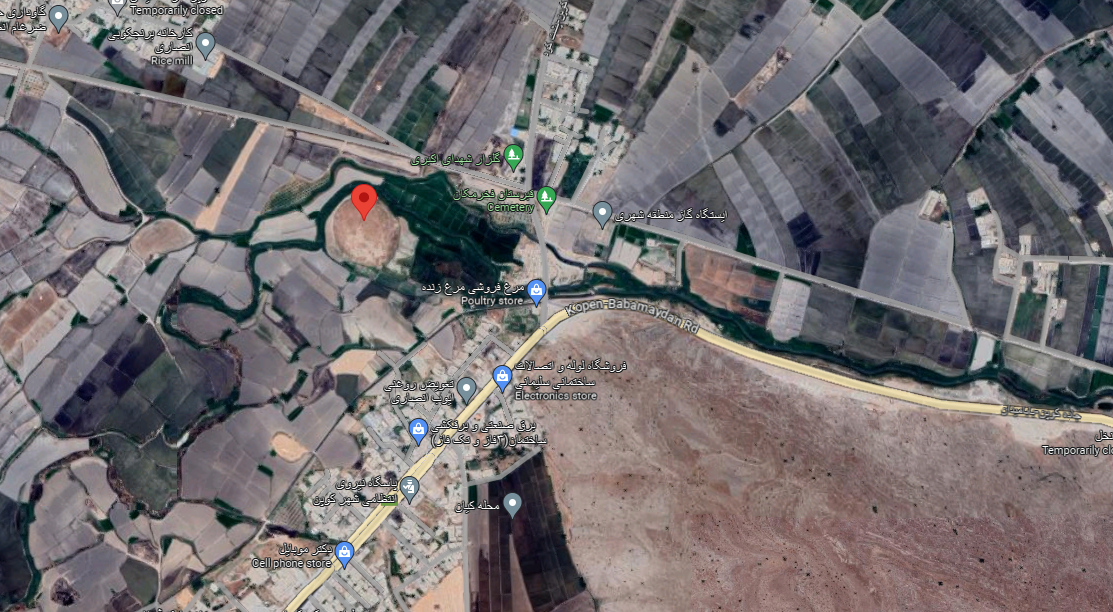

Location: Rōbāt Sharaf is 45 km northwest of Sarakhs, in northeastern Iran, Razavi Khorasan Province.

36°15’57.2″N 60°39’19.4″E

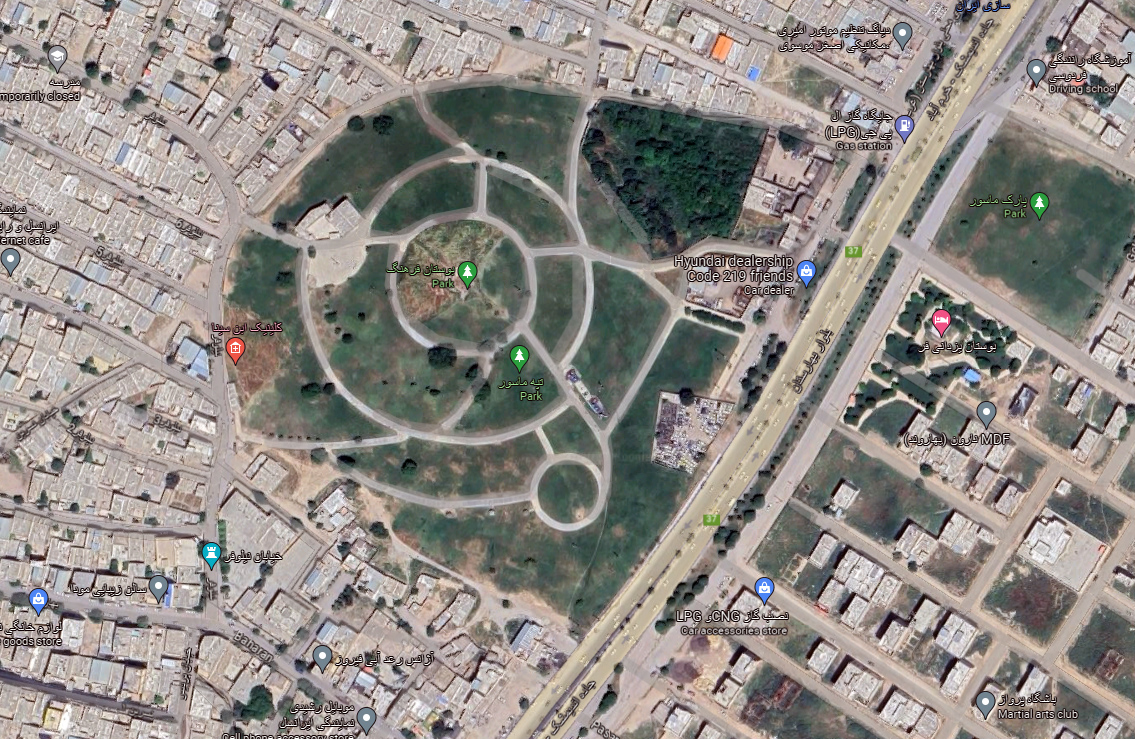

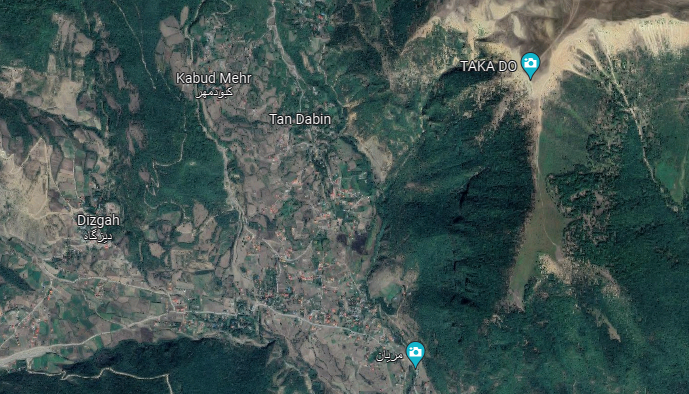

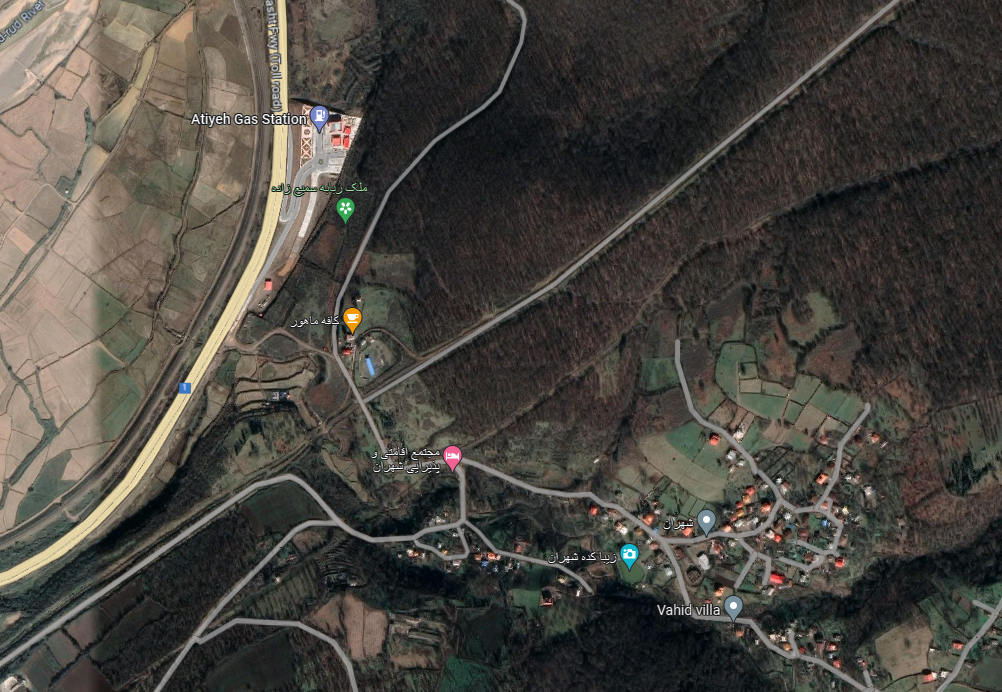

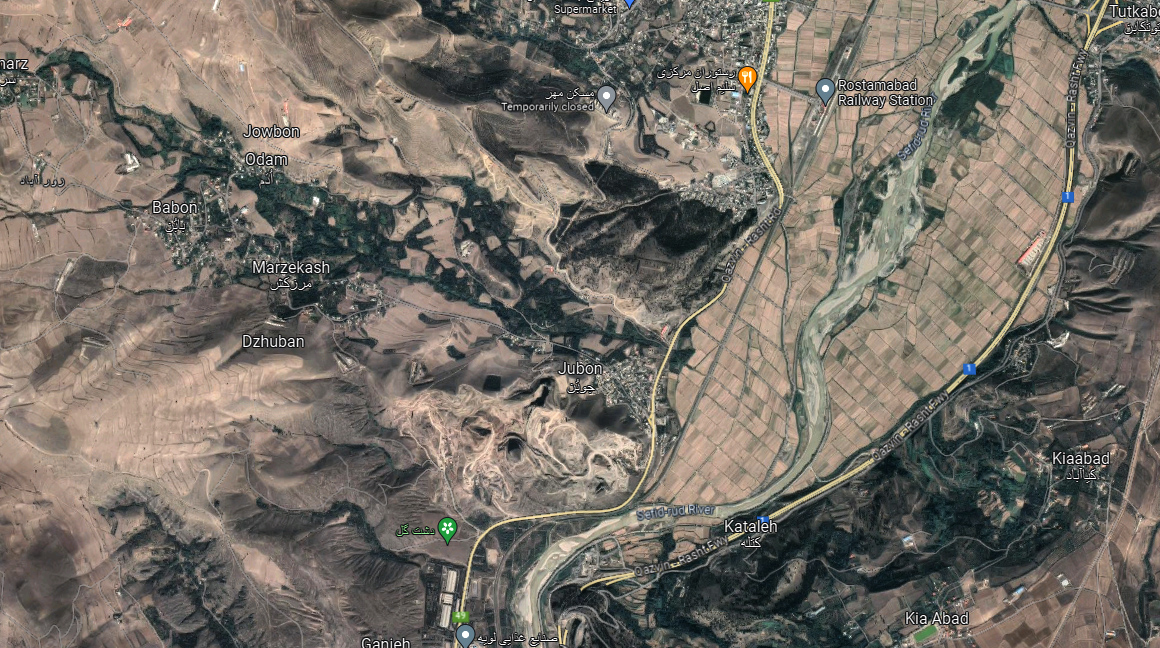

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

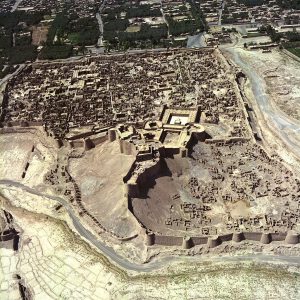

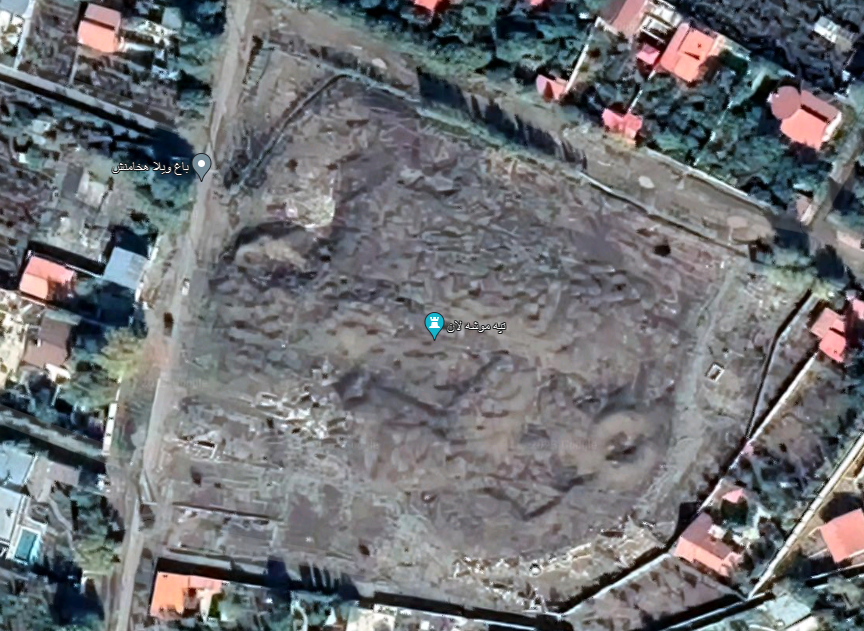

Rōbāt Sharaf is 45 km southwest of Sarakhs. The caravanserai's location appears to be one of the most ill-chosen places to settle, yet in earlier times, it lay along the route from Nishapur to Merv—the great highway of Khorasan (fig. 1). Along this road, which crossed a desolate region, it was essential for travelers, the ruler’s envoys, and even the Sultan himself to find safe places to rest each night. Rōbāt Sharaf was one such caravanserai.

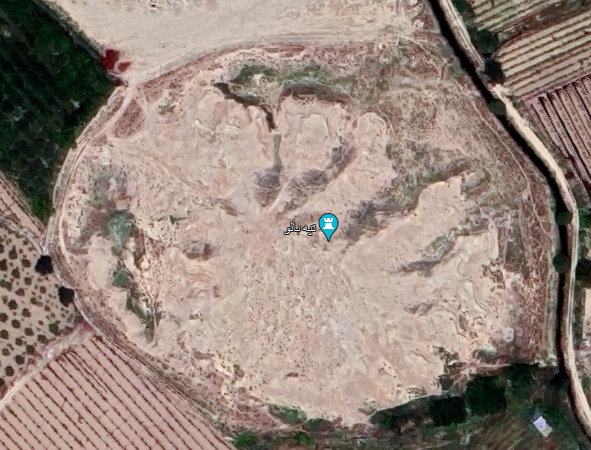

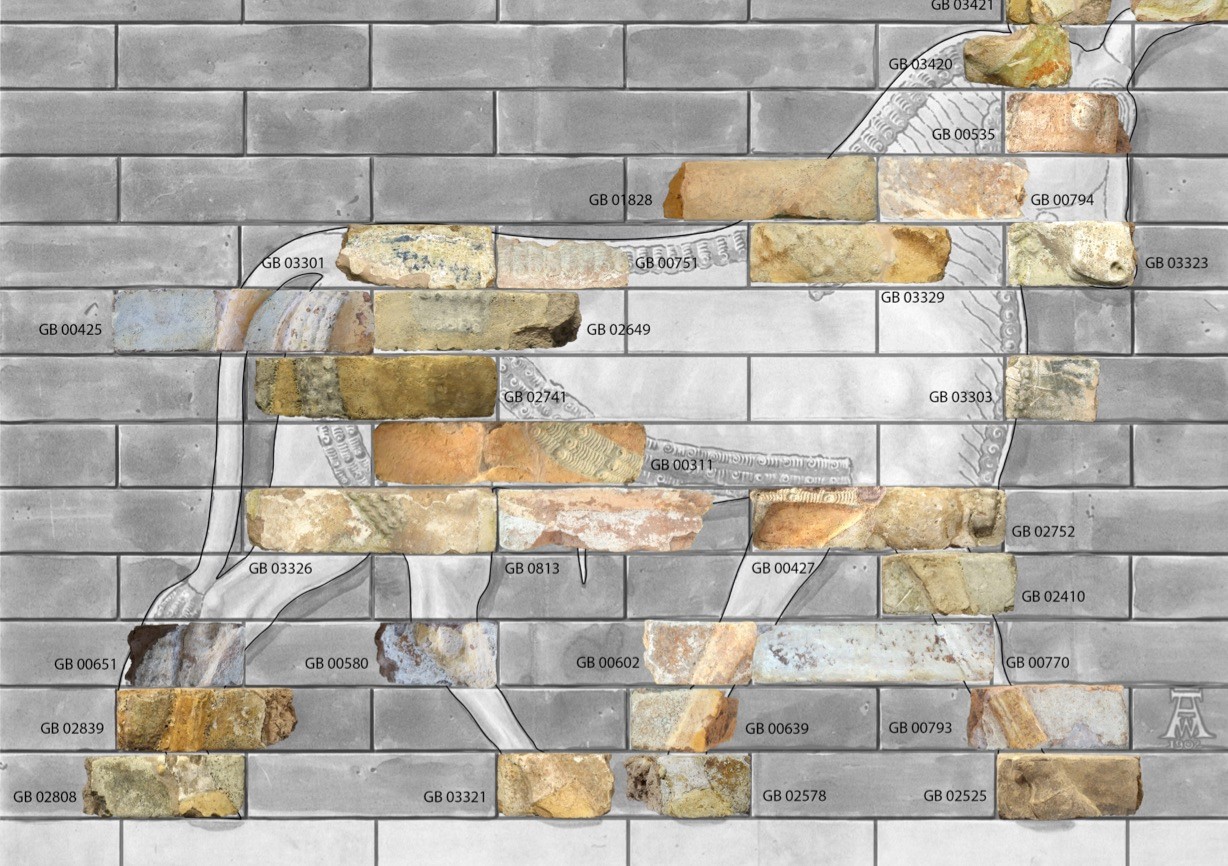

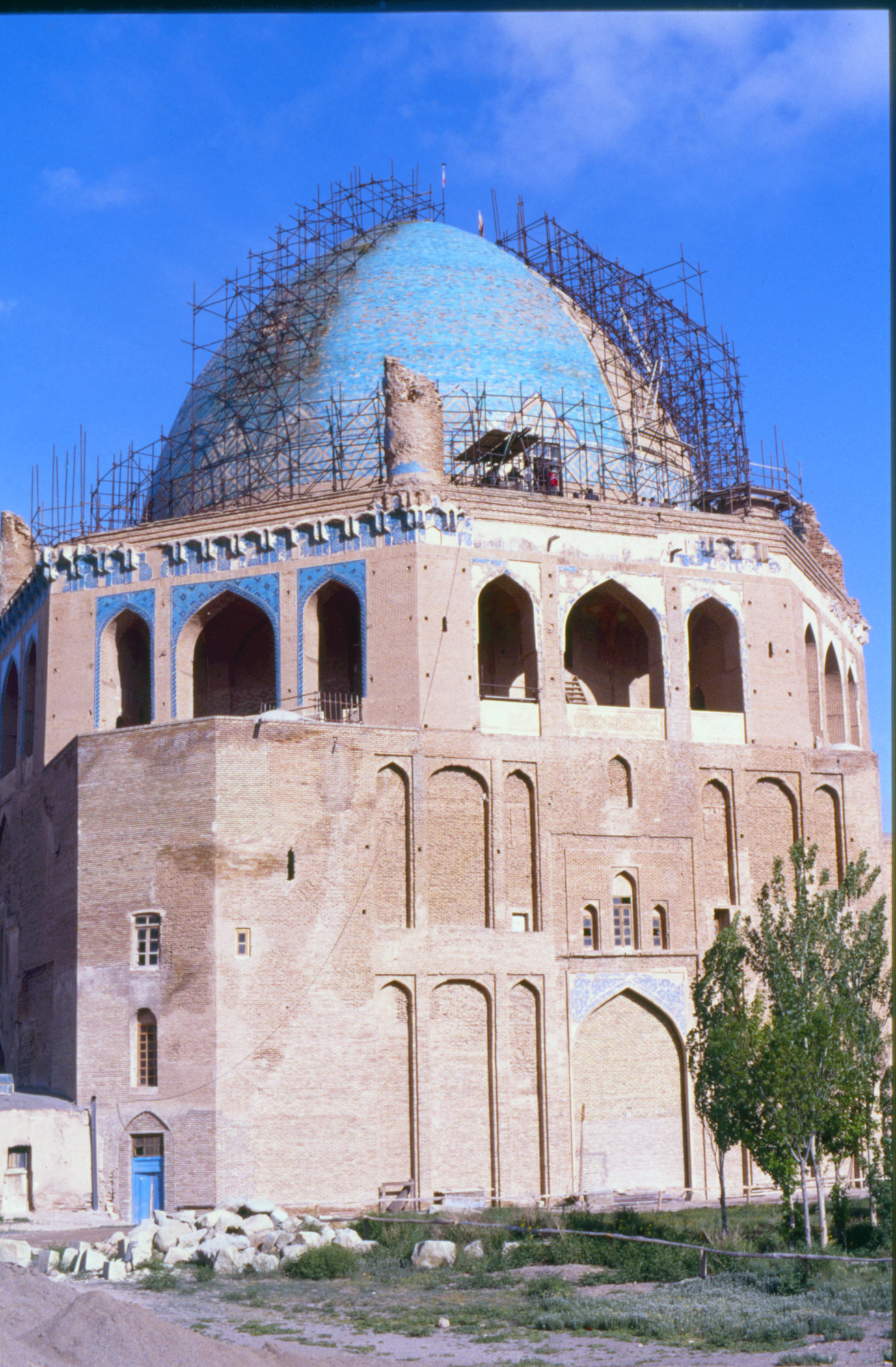

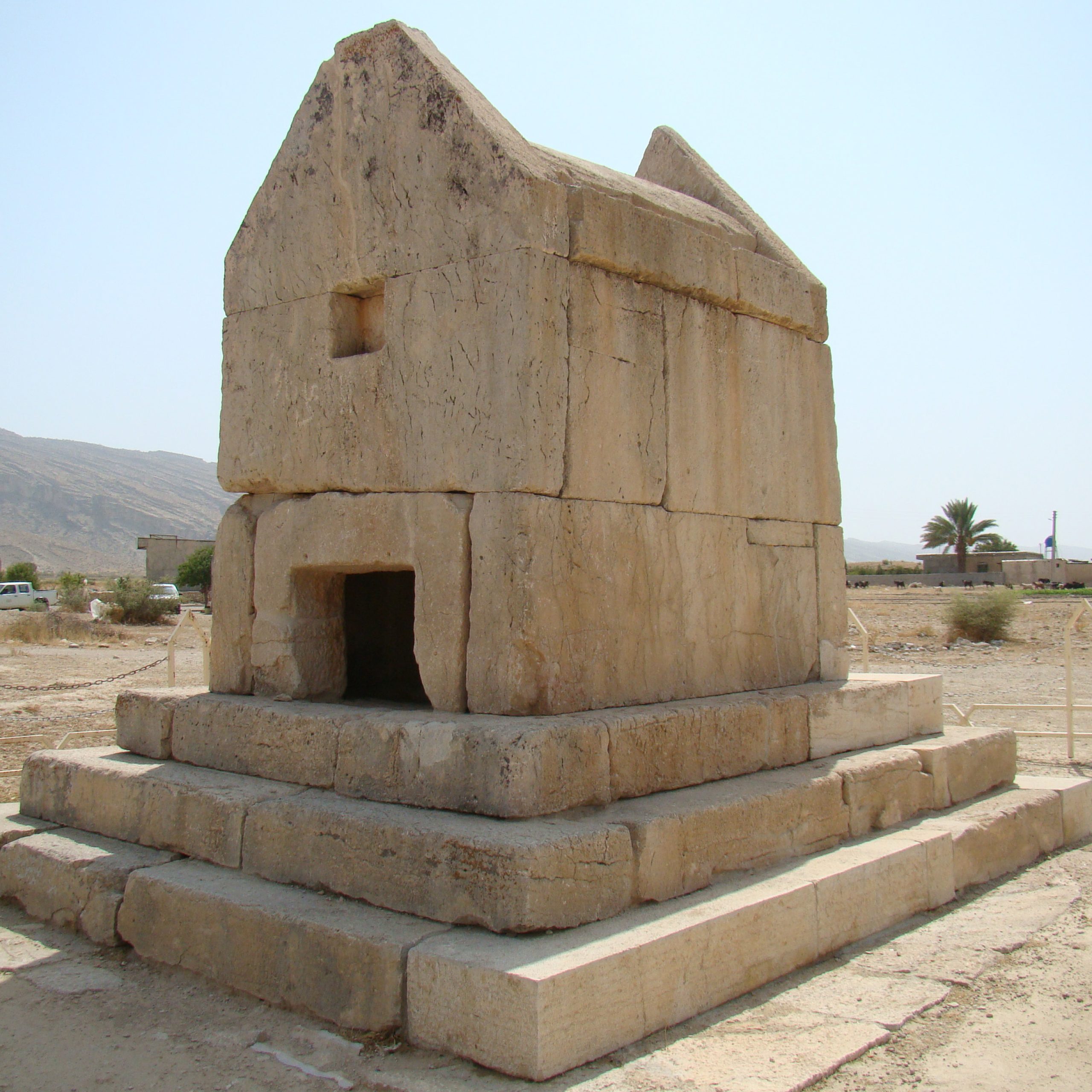

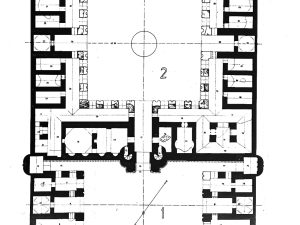

The caravanserai had a square detached courtyard once bordered by arcades, now destroyed (fig. 2); this part may have been used as stables. Beyond it lies a double-courtyard structure built of fired brick, with arcaded walkways surrounding the inner courtyard and four eyvāns (fig. 3). There are also eyvāns in the forecourt. Five-sided and round-cornered and tower structures, and projecting portal buildings on both the outer façade and the courtyard façade. The building covers approximately 4863 square meters. The caravanserai’s external dimensions are 98 x 62 m. The forecourt measures 12.50 x 19 m. The inner court is 31.50 x 17.50 m. The height of the enclosing wall was approximately 8.50 m, and the height of the outer portal building was about 13.50 m. The caravanserai’s main eyvāns were decorated with brickwork and stucco (fig. 4). There are inscribed areas on the portal of the forecourt and inner court.

The caravanserai had two mosques: one located in the corridor along the west side of the entrance to the first courtyard, and the other in the hallway west of the entrance to the second courtyard. The latter mosque possessed two mihrabs, both decorated with stucco.

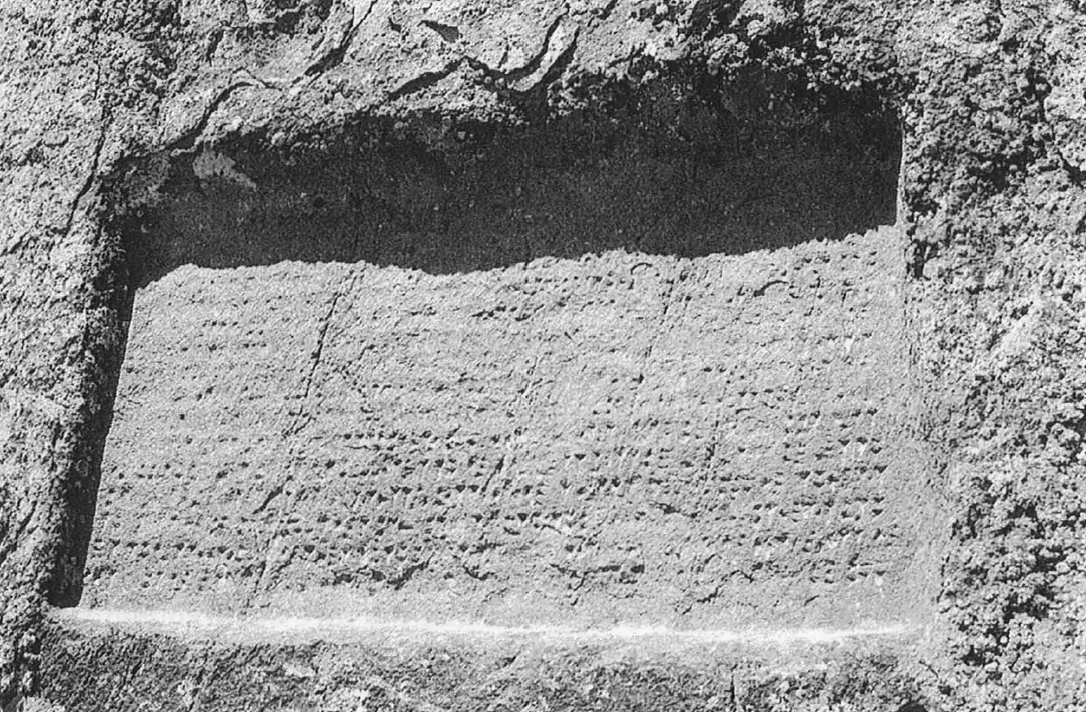

The earliest mention of the caravanserai, known as Rōbāt-e Abgineh, appears in Hamdullah Mostowfi’s Nūzhat al-Qōlūb, where he describes various routes connecting Nishapur to Merv. André Godard identifies Rōbāt Abgineh—meaning “crystal” or “diamond,” likely named so because of its beauty—with the present-day Rōbāt Sharaf. It is likely that at the time of its construction, more than two centuries before the composition of the Nuzhat al-Qulub, it bore yet another name. Another theory regarding the origin of the name comes from the Iranian archaeologist Mahmoud Rad, who was active in the 1930s. In a letter to Godard, Rad proposed that Sharaf may refer to the builder of the monument. He identified this figure as Sharaf al-Din Abū Ṭāher b. Saʿd al-Din b. ʿAli al-Qomi, a powerful governor of Merv who held office for forty years and was appointed vizier to Sultan Sanjar in 515 A.H./1121 A.D. Given the scale and significance of the structure, it is indeed plausible that it could only have been commissioned by a person of considerable influence. An inscription in Arabic ⸺ the only one in Thuluth script ⸺ placed under the arch of the north eyvān in the main courtyard dates the monument to 549 H./1154 A.D., during the reign of the Saljuq ruler, Sultan Sanjar. Restoration work in the 1970s suggests that the inscription was a later addition and that the structure may have been built earlier.

Another inscribed band on the main eyvān gives the name of the builder as Abu Mansur As’ad ibn Muhammad al-Ta’ifi al-Srakahsi.

Rōbāt Sharaf, like many other monuments in Khorasan, suffered from devastation brought by the Ghūzz Turkmens who invaded Saljuq territories in the years 1153-55 A.D. But, as the excavated documents show, the caravanserai was repaired and in use until the sixteenth century at the latest. Seventeen documents were found among a treasure trove at Rōbāt Sharaf. One of the most notable documents is a royal decree issued by Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid dynasty, dated 917 H./1512 A.D. This decree contains instructions regarding Zayn al-Din Ali Takallū, who held the position of dārūghā (governor) in Khorasan. Addressed to governors, emirs, officials, and leaders of various regions, it states that from the beginning of Nowruz, all ministers and administrators of Khorasan, who are part of the king's inner circle, will come under the direct authority of ‘Imad al-Mūlk (the governor). The decree also specifies that their estates will be considered royal properties.

Fig. 1. Rōbāt Sharaf in the 1940s (image: Godard, “Khorasan,” p. 8, fig. 1)

Fig. 2. Rōbāt Sharaf. View from the southeast (image: CreativeCommons).

Fig. 3. Rōbāt Sharaf. Plan of the caravanserai (image: Daneshdoost, “Rōbāt Sharaf,” plan, p. 13).

Fig. 4. Rōbāt Sharaf. Northern eyvān of the inner courtyard (image: H. Moradkhani).

Archaeological Exploration

Rōbāt Sharaf was first thoroughly examined and published by André Godard, then director of the Antiquities Service in Iran in 1949. In the 1970s and 1980s, Wolfram Kleiss and Mohammad-Yusef Kiani studied and recorded Rōbāt Sharaf in their survey of Iranian caravanserais. Yaqub Daneshdoost, the Iranian architect of historical monuments, carried out significant restoration work, involving controlled excavations, on behalf of the Iranian National Office for the Protection and Restoration of Historical Monuments carried out restoration work at Rōbāt-e Sharaf in 1971, 1975, and 1981. In 2023, Rōbāt Sharaf was inscribed on the World Heritage List of UNESCO.

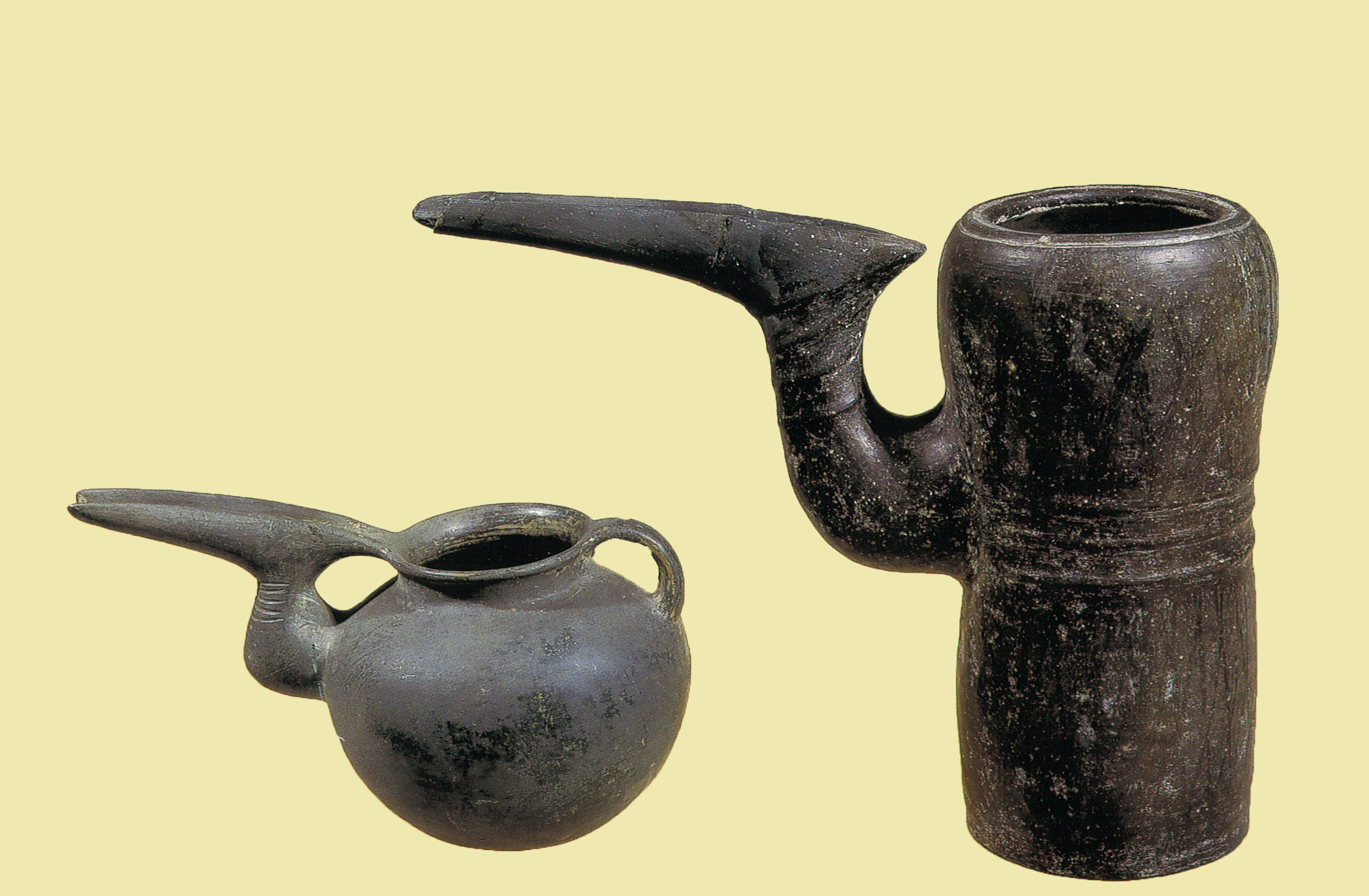

Finds

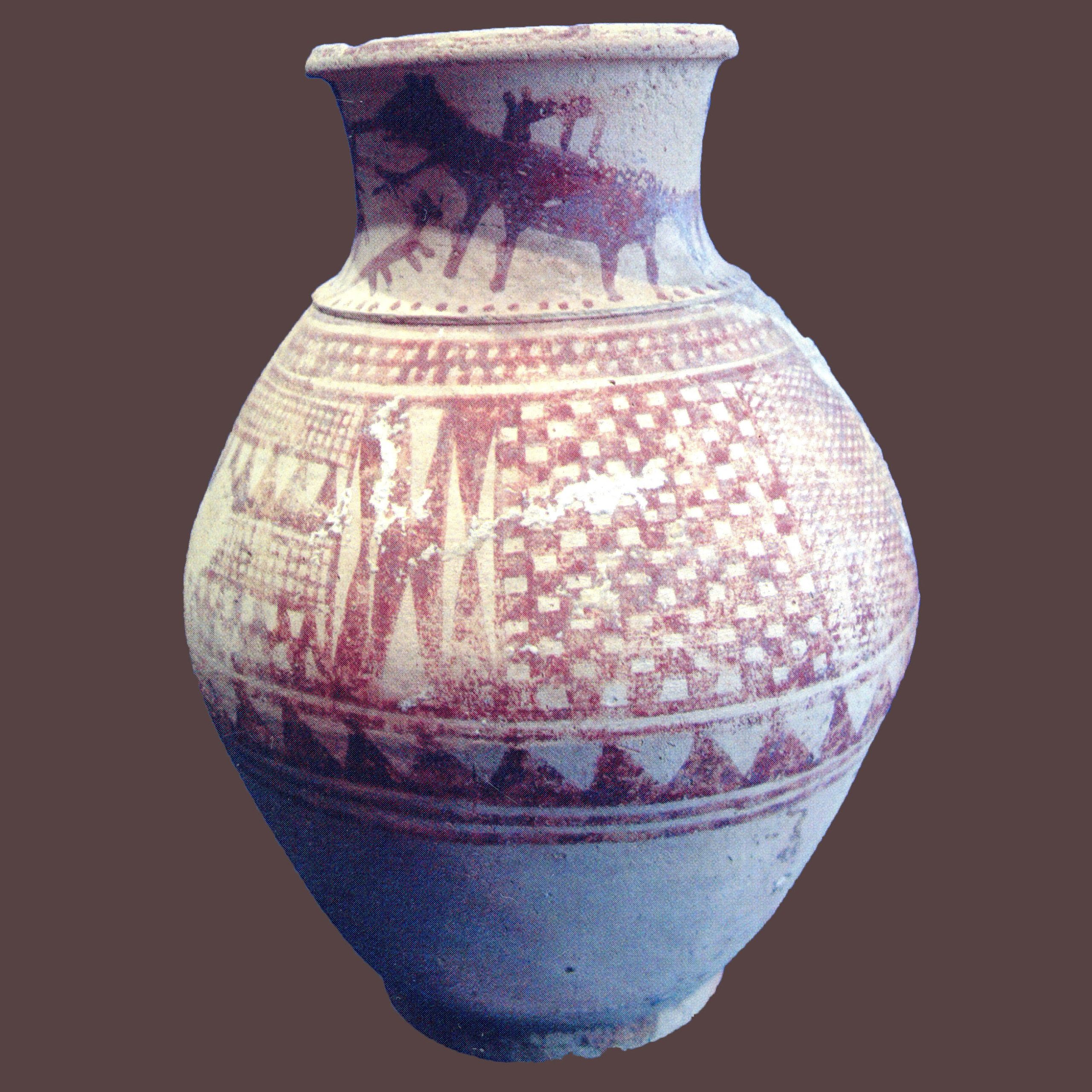

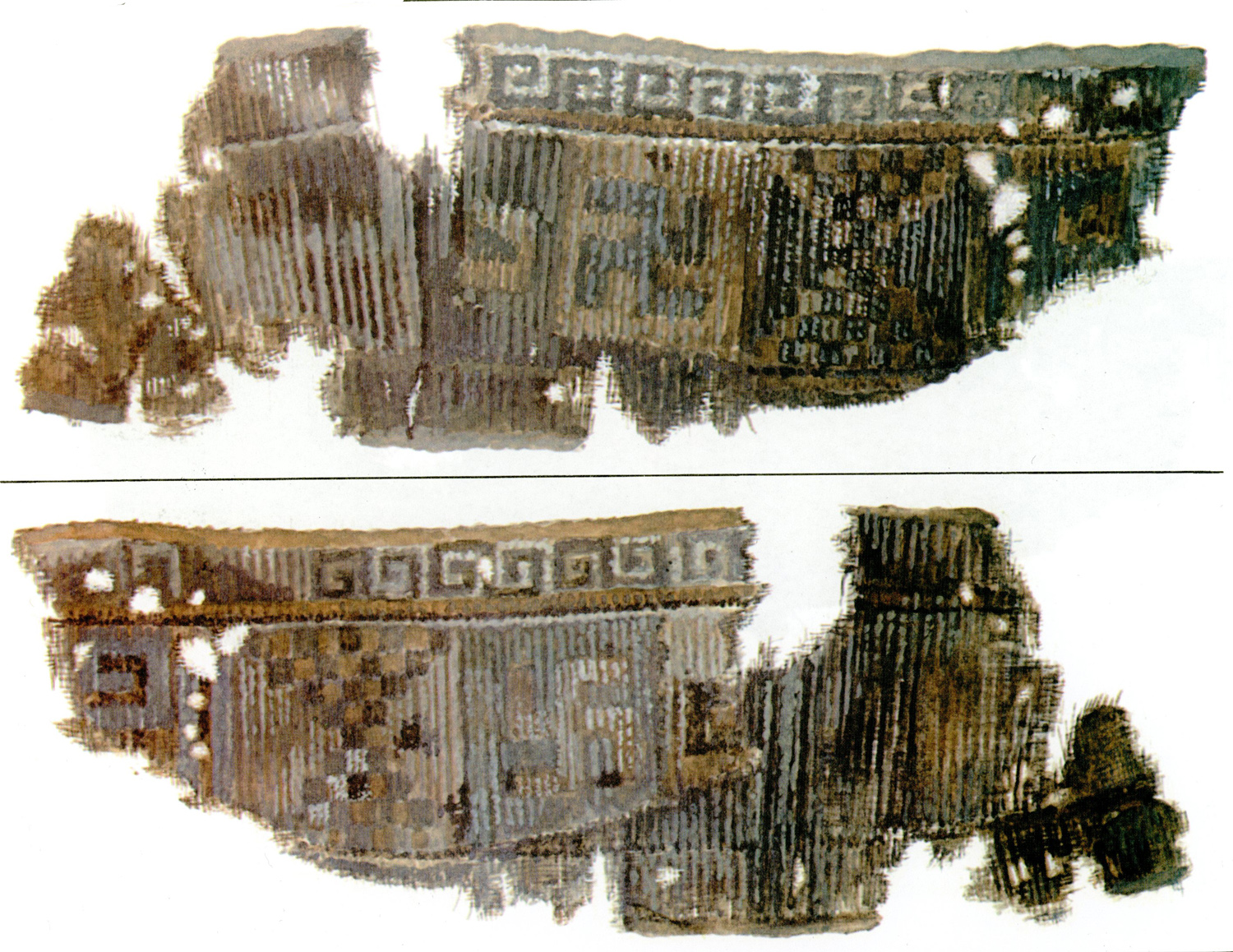

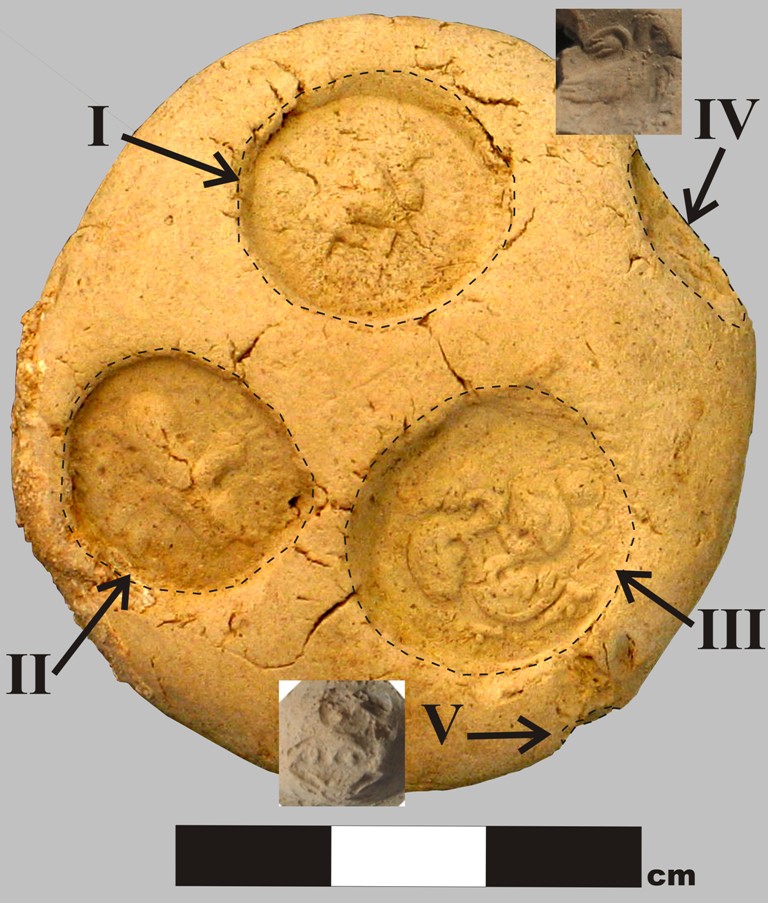

The excavated finds from Rōbāt Sharaf consist of glazed pottery, a lacquer wooden vessel, 57 metalware pieces in silver or copper, 16 scrolls, and 1 firman (royal decree).

Bibliography

Afshar, I., “Farmāni az dowre-ye safaviyeh,” Yādgārhā-ye Rōbāt-e Sharaf/Discoveries from Rōbāt-e Sharaf, edited by M. Y. Kiani, Tehran, 1360/1981, , pp. 54-64 (in Persian).

Daneshdoust, Y., “Rōbāt Sharaf,” Yādgārhā-e Rōbāt-ye Sharaf/Discoveries from Rōbāt-e Sharaf, edited by M. Y. Kiani, Tehran, 1360/1981, , pp. 1-39 (in Persian).

Fehervari, G., “Sōfālineha-ye Rōbāt Sharaf,” Yādgārhā-ye Rōbāt-e Sharaf/Discoveries from Rōbāt-e Sharaf, edited by M. Y. Kiani, Tehran, 1360/1981, , pp. 65-71 (in Persian).

Fehervari, G. and M. Y. Kiani, “Felezzāt-e makshūfeh az Rōbāt Sharaf,” Yādgārhā-ye Rōbāt-e Sharaf/Discoveries from Rōbāt-e Sharaf, edited by M. Y. Kiani, Tehran, 1360/1981, , pp. 72-106 (in Persian).

Godard, A., “Khorasan,” Āthār-é Irān, vol. 4, 1949, pp. 7-75.

Kiani, M. Y., “Zarf-e lāki-ye Rōbāt Sharaf,” Yādgārhā-ye Rōbāt-e Sharaf/Discoveries from Rōbāt-e Sharaf, edited by M. Y. Kiani, Tehran, 1360/1981, pp. 40-53 (in Persian).

Kiani, M. Y., W. Kleiss, Iranian Caravanserais, vol. 3, Tehran, 1994, p. 370.

Kleiss, W., Karawanenbauten in Iran, vol. 6, Materialien zur iranischen Archäologie 8, Berlin, 2001, p. 42.

Mostowfi, Hamdullah, The Geographical Part of the Nuzhat-al-qulūb, composed by Hamd-Allāh Mustawfī of Qazwīn in 740 (1340), translated by Guy Le Strange, E. J W. Gibb Memorial series 23, Leyden-London, 1919, p. 169.