Sangbastسنگ بست

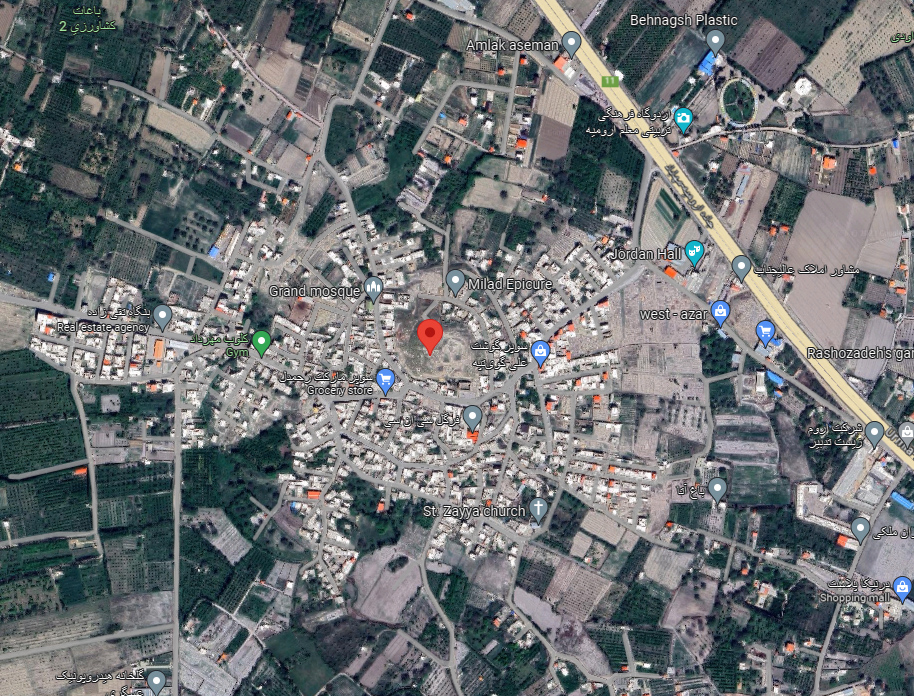

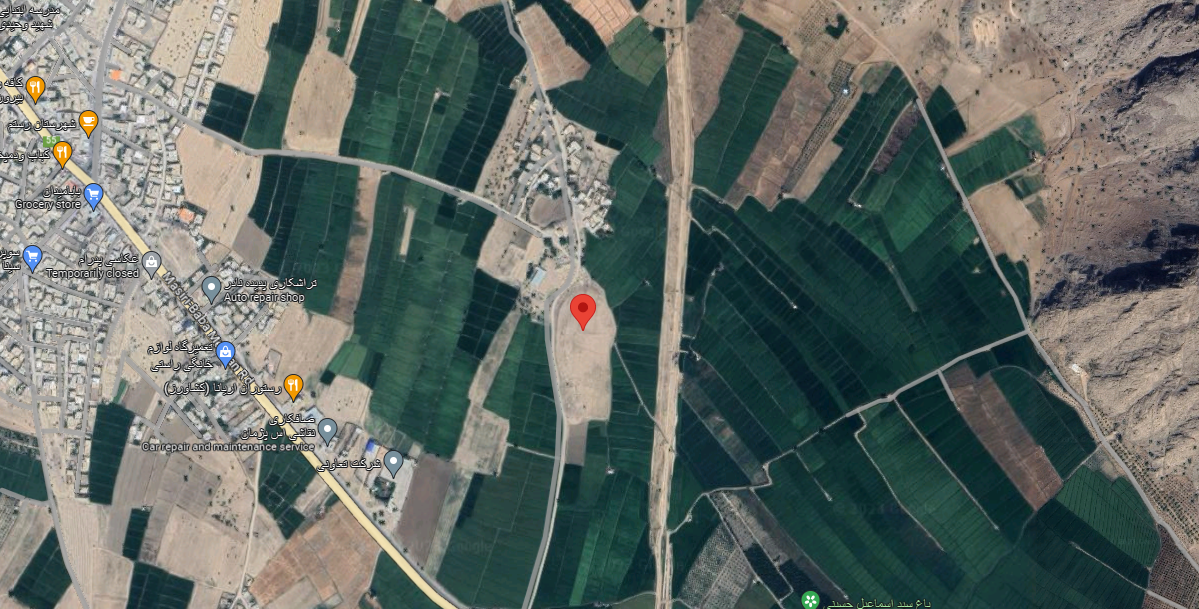

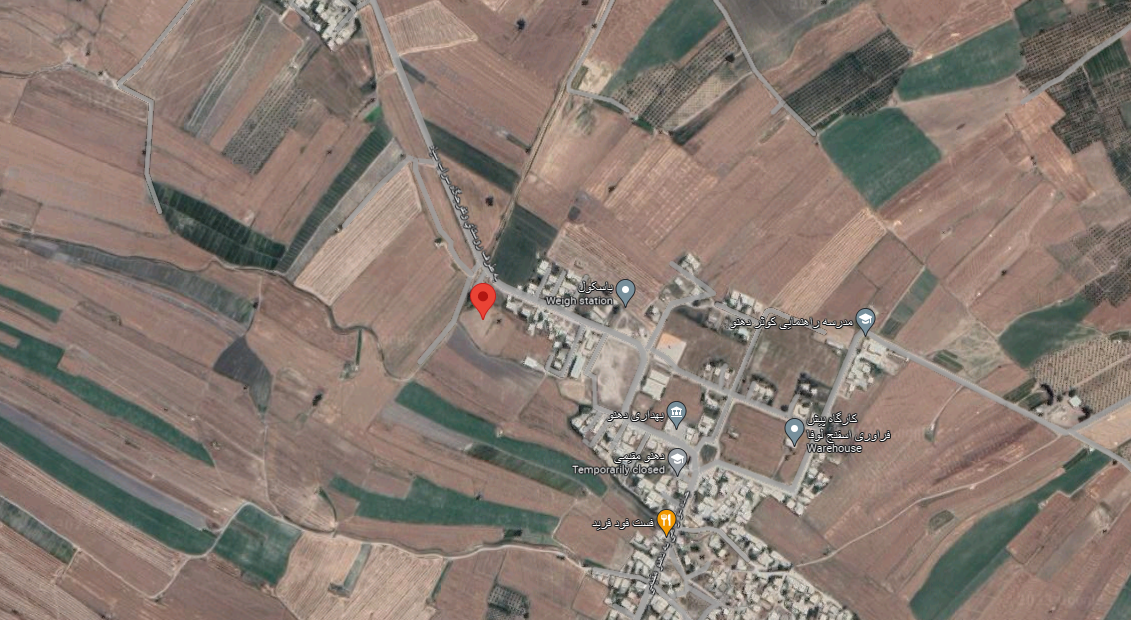

Location: Sangbast is located south of Mashhad, in northeastern Iran, Razavi Khorasan Province.

35°59’33.1″N 59°46’43.1″E

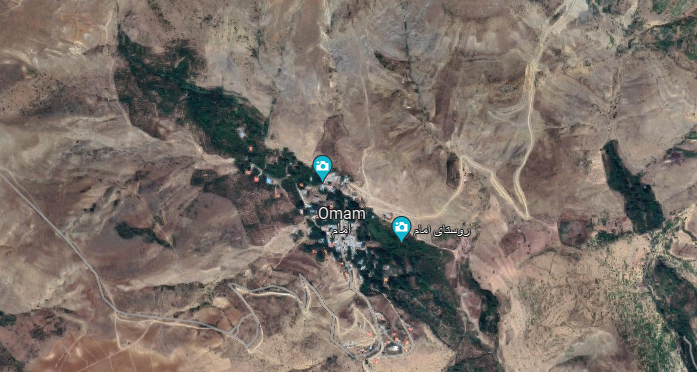

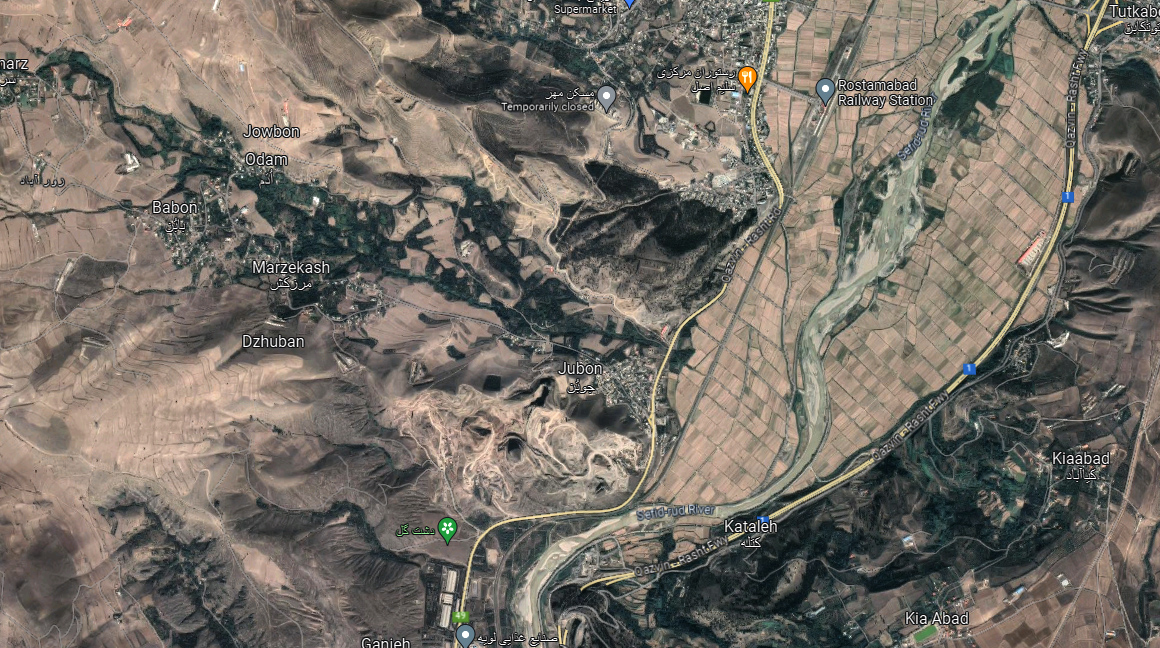

Map

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

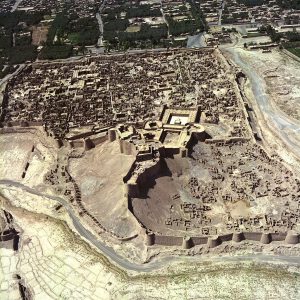

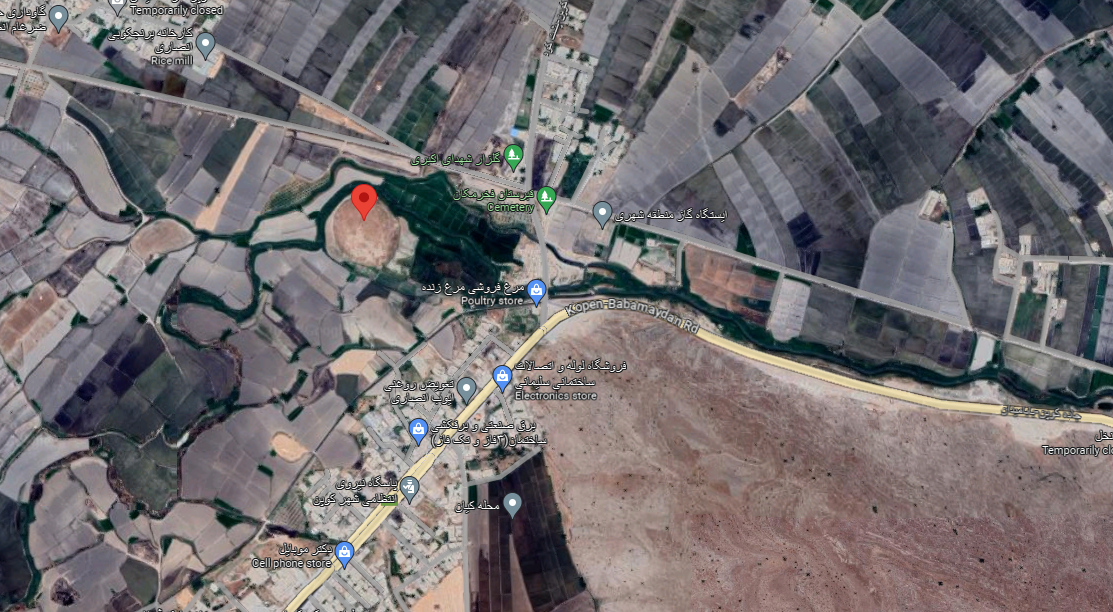

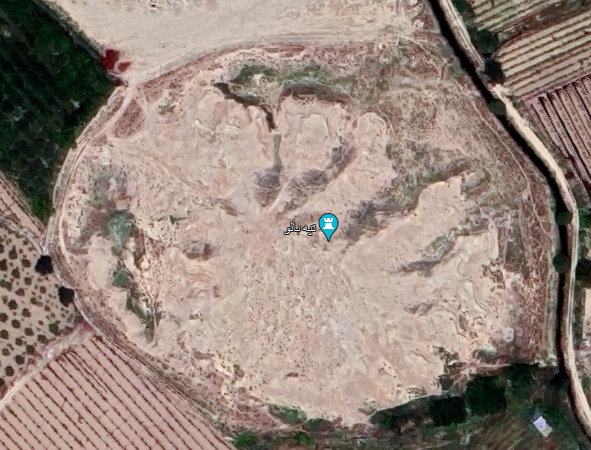

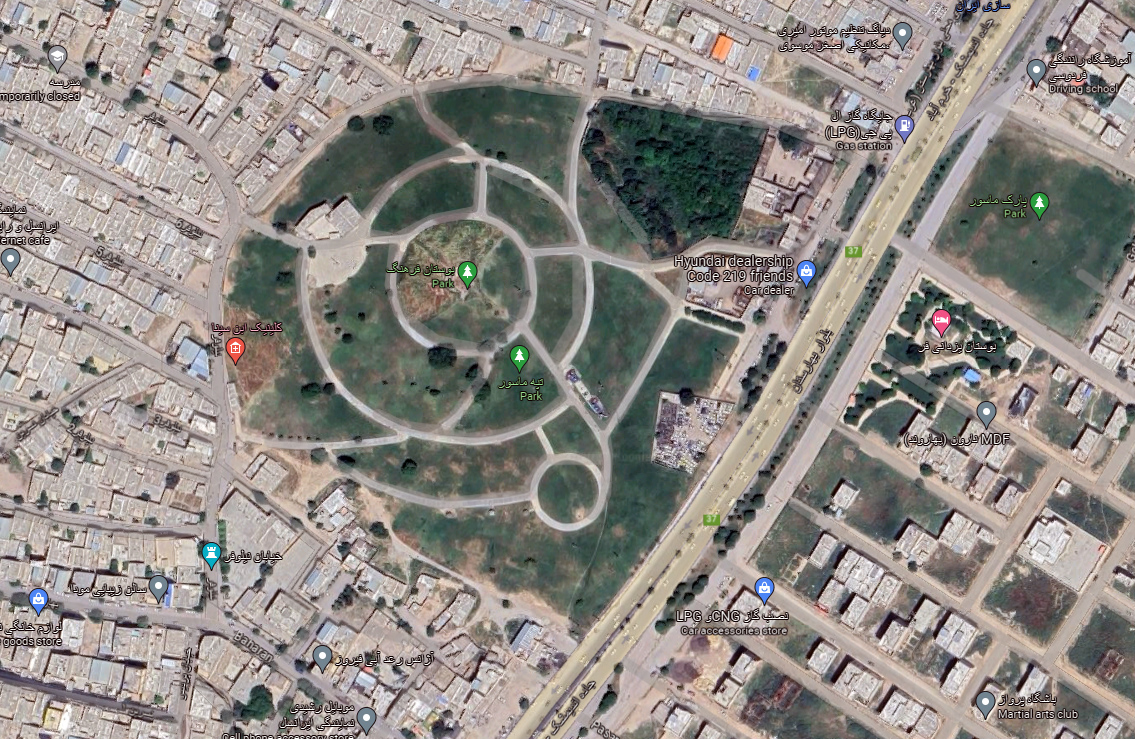

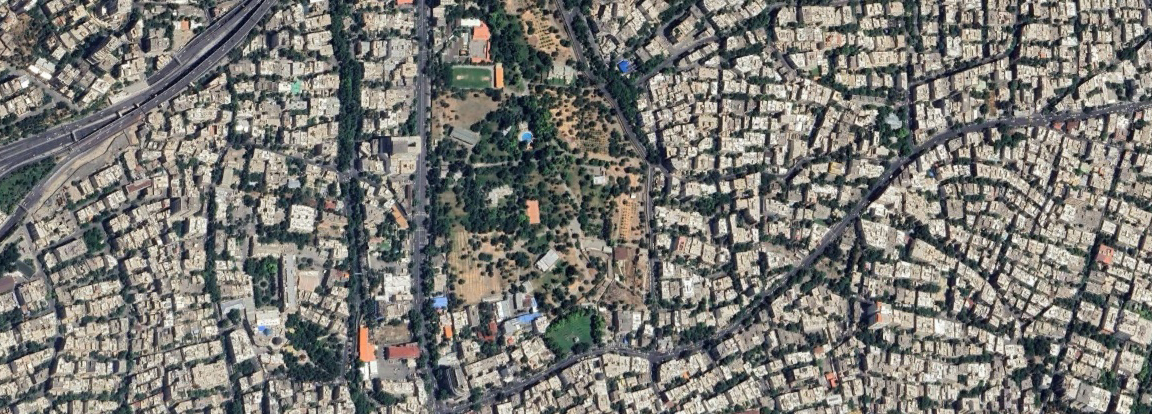

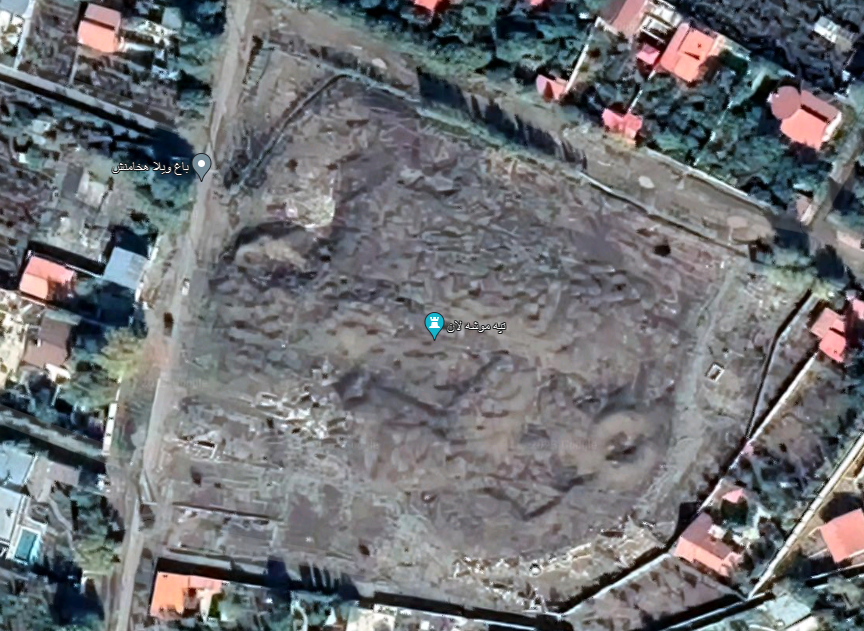

The ruins of Sangbast are situated approximately 49 km south of Mashhad, along the east-west road between Herat and Nishapur. The remains consist of two areas (fig. 1): a large east-west rectangle that measures 400 x 250 m approximately in size, and another one, 300 x 160 m. The former walls of the site can still be seen today as undulating brick formations and piles of rubble rising from the terrain. These remains allow the original layout of the entire complex to be discerned, as shown in the plan. The first rectangle displays the layout of a walled city with ruined buildings inside the city wall. This area represents a new city that was mostly constructed after the Mongol invasion due to population growth and was fortified with defensive walls. It likely flourished between the late thirteenth and seventeenth centuries. By the 1800s, the city had declined and its population either dispersed or moved into the nearby caravanserai. The second area appears earlier in date and consists of two courtyards − an oblong one and a square one − surrounded by chambers, covering a total of 5 hectares.

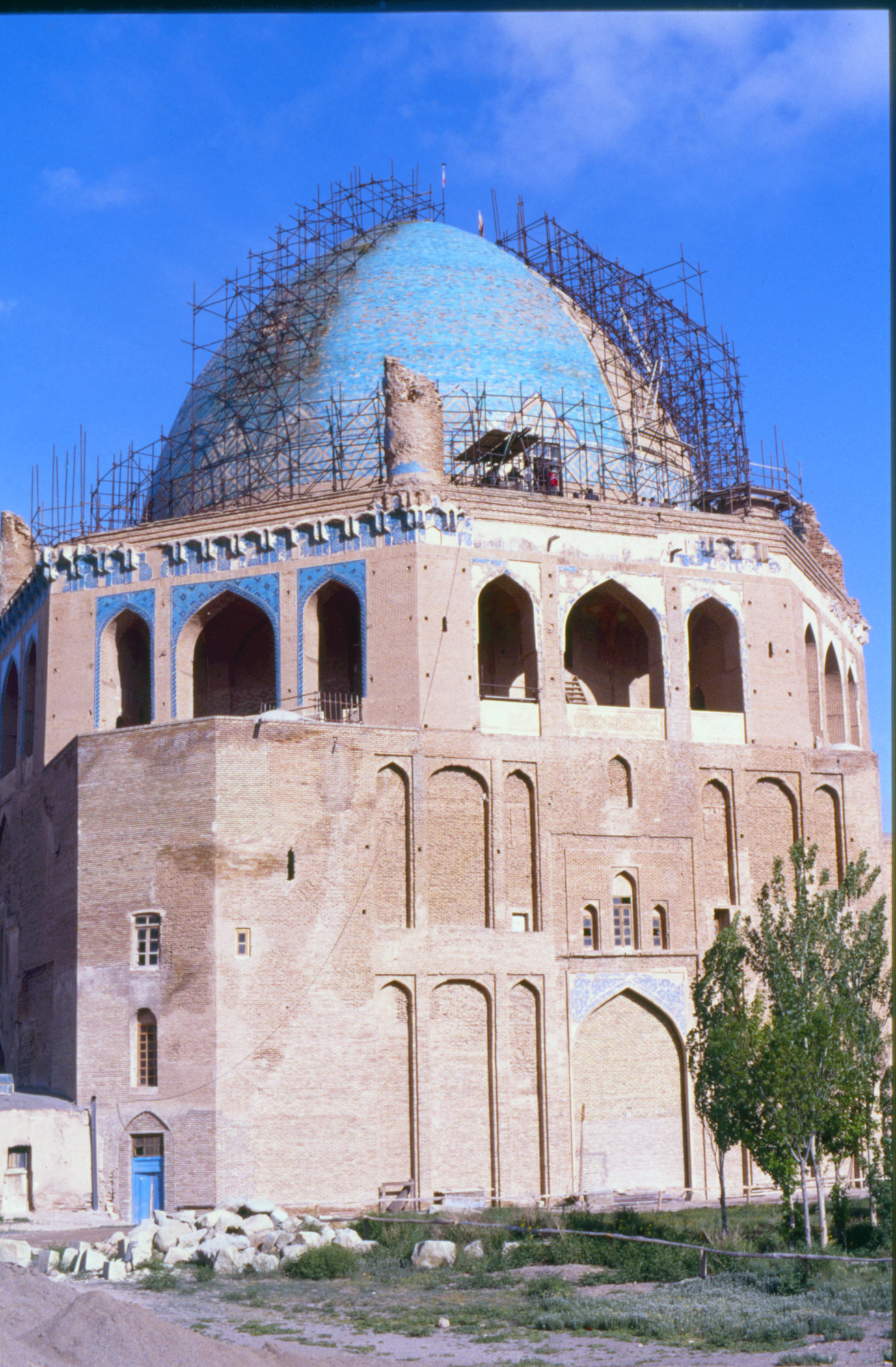

The two standing structures are a tomb tower and a minaret (fig. 2). The tomb tower and the nearby freestanding minaret were originally incorporated into a mosque. Recent archaeological excavations show that the mosque had a single eyvān (iwān) with thick and tall piers with prayer halls on either side. A pulpit in stone found in excavations was likely destroyed during the early Islamic centuries and replaced in the fourteenth century with a new pulpit made of brick and plaster. It appears that the Sangbast mosque underwent multiple renovations until the early Safavid period when it began to decline.

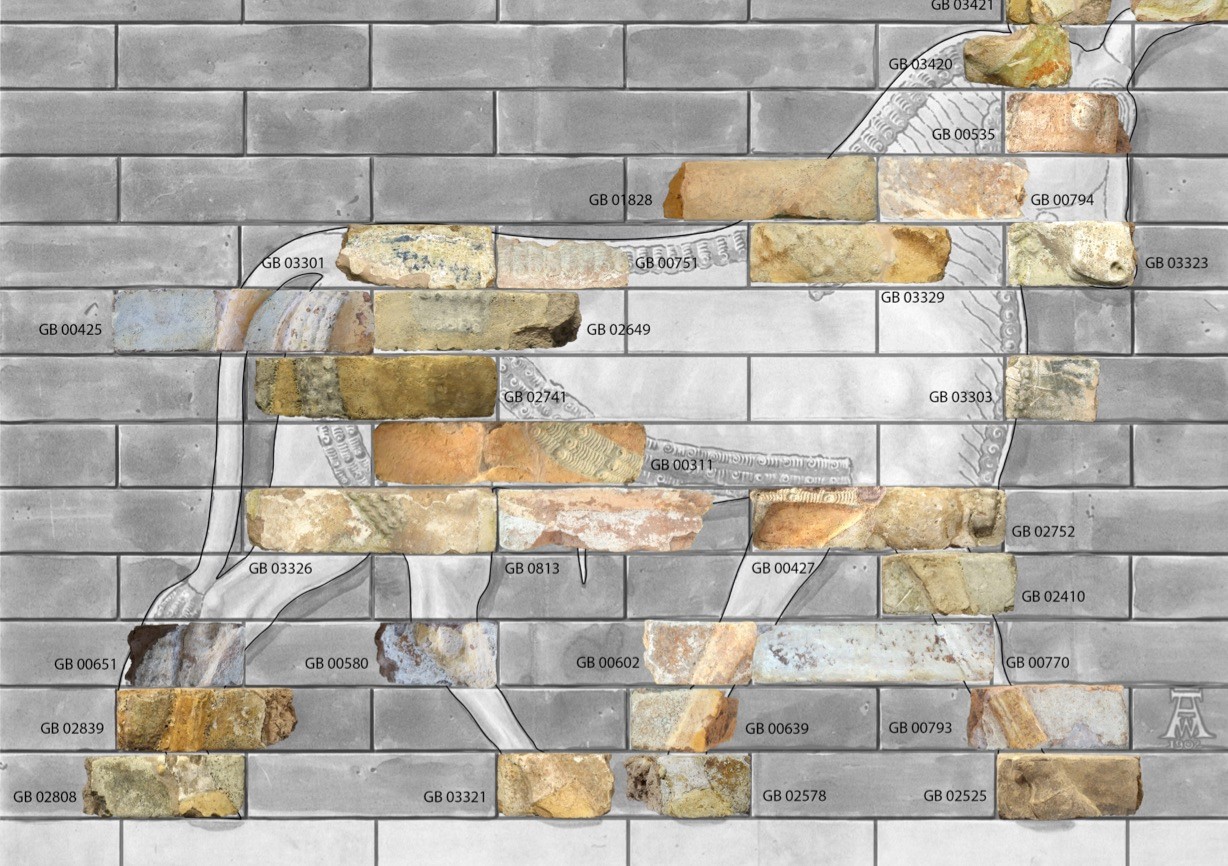

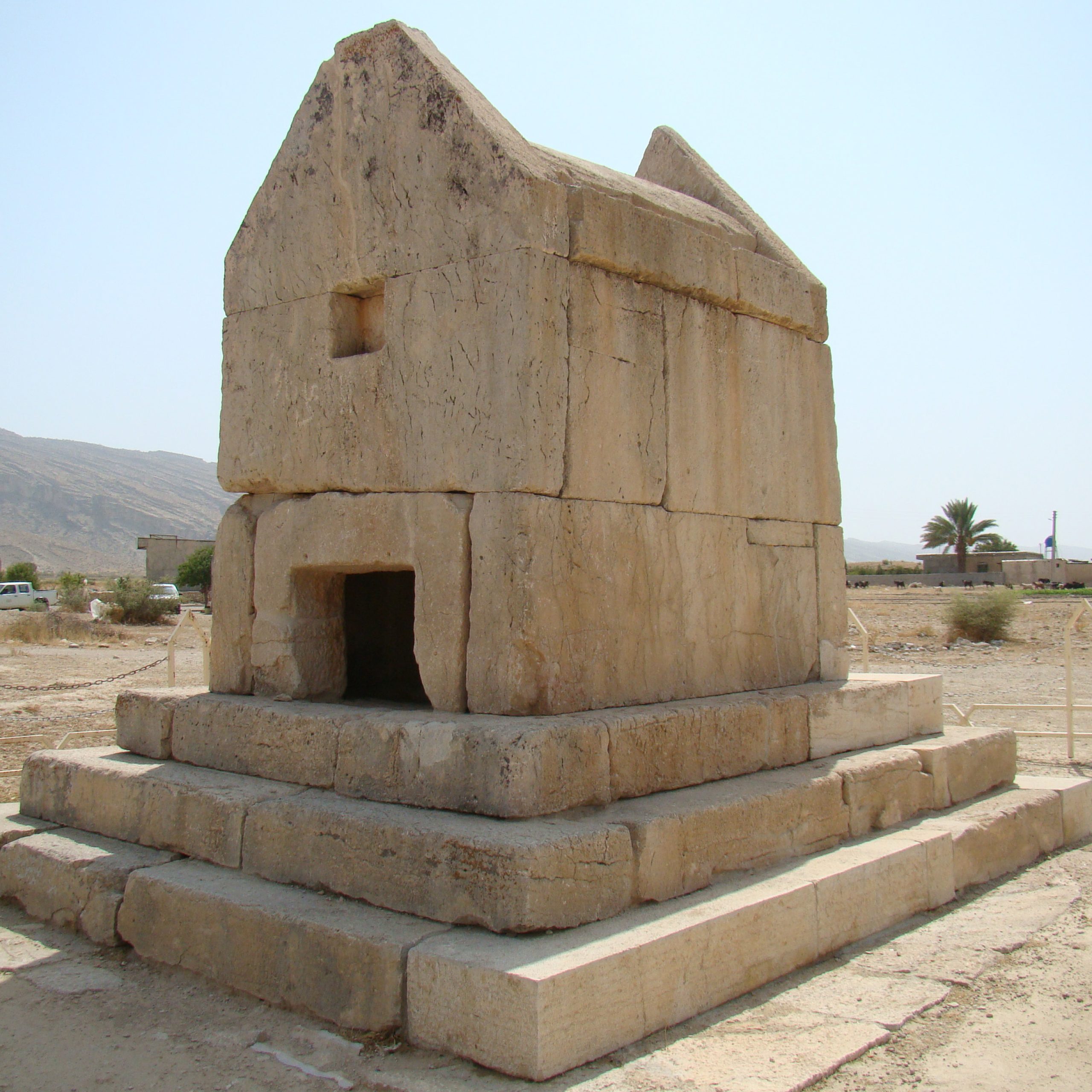

The first large surviving monument is a square brick structure with a side length of 12.50 meters, topped by a dome with thicker brick courses near its base. This design reflects an early understanding that tapering or reducing the thickness of a dome toward its crown enhances its structural strength. An Arabic inscription in kufic runs below the dome. The monument was likely a mausoleum and has been attributed to Arsalan Jazib, a military commander in the service of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna (r. 998 –1030).

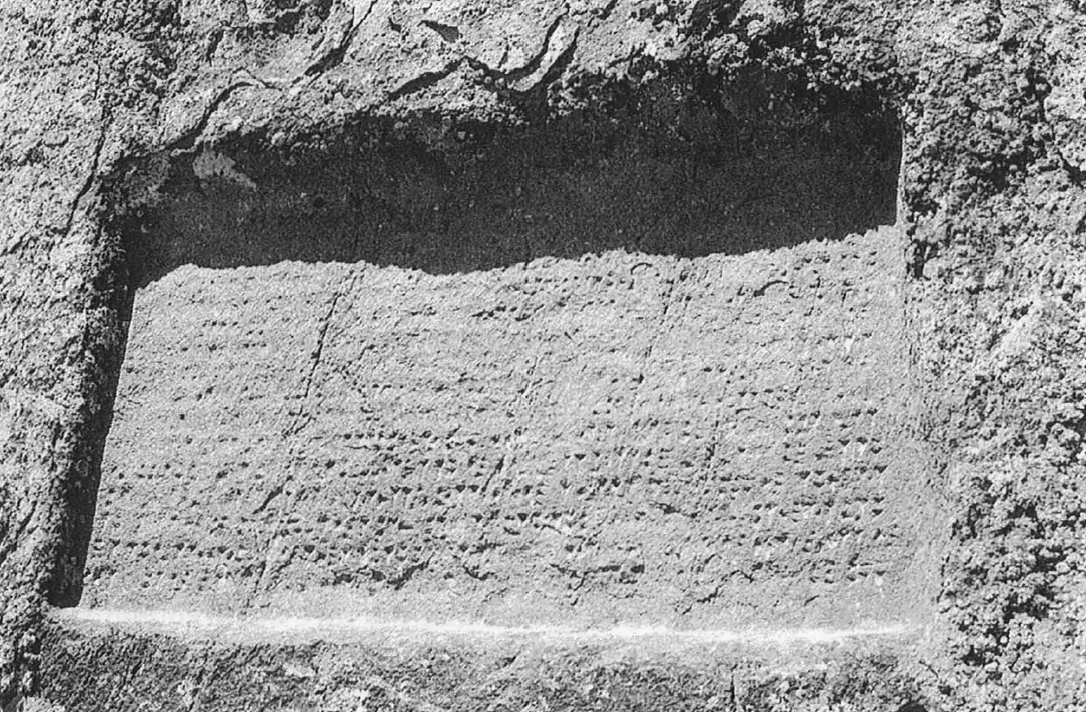

The still-standing minaret once flanked the gate leading to the first courtyard. The minaret is cylindrical and tapers as it rises to a height of 22 meters. There is a short inscription on the minaret executed in bricks of varying sizes, laid on the edge. They stand out in relief against a background of regular courses. The current state of conservation does not allow for a coherent reading of the entire text. A sketch attributed to Ernst Herzfeld reveals that it consists of a Koranic text followed by the name of the builder or brickmaker, a certain Ahmad Sarakhsi.

The association of the ruins with the name of Arslan Jazib, the governor of Tūs, is based on a passage in Tarikh-e Yamini, written by the historian Abu Nasr Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Jabbar al-'Utbi. This work chronicles events during the reign of Sebuktegin, the founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty, and part of the reign of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazna, up to A.D. 1020. Besides, a commentary on Tarikh Yamini by the eighteenth-century writer, Ahmad ibn Ali Manini, clearly attributes the ruins to Arsalan Jazib: in his book on Yamini’s history Fath al-Wahbi, while describing the events of the Ghaznavid era, wrote about the construction of this complex as follows (Manini, Sharh al-Yamīnī, pp. 311-312):

Arsalan Jazib was someone who was appointed by Sultan Mahmud as the governor of Tus for several years, and his achievements in that region are many. Among them are a caravanserai in the village of Sanjabast, a congregational mosque, and a khanqāh. Many buildings were constructed, and his shrine is located there.

It is said that when merchants were taking him to Ghazna, bandits attacked them, stole their goods, and left. They tied Arsalan to a rock. He made a vow before God to build a caravanserai there, bring out water, and turn the area into a safe and thriving place for travelers.

When he gained power and became the ruler of Tus, he fulfilled his vow and built this settlement in Sangbast. The name refers to the event that occurred when he was tied to the rock, and he also built water reservoirs and resting places there, dedicating the village to these structures.

Archaeological Exploration

In modern times, the first recorded visit of the ruins is by a Qajar prince, Abdul Mohammad Mirza Seyf al-Dowla, who passed through the region in 1880, and described the geographic location and routes leading to Mashhad: (Seyf al-Dowla, Safarnameh, p. 321):

On the journey from Mashhad to Herat, the first place is called Sangbast. Sangbast itself is not a populated place, except for a small number of peasants who reside in the Safavid caravanserai. Some ruins include minarets, but the area is otherwise uninhabited.

In 1893, Colonel Charles Edward Yates of the British Army visited the ruins on his way to Mashhad and described it as follows (Yates, Khurasan and Sistan, p. 39):

About a mile out of Bakirabad we passed a ruined brick robot and then the village of Sangbast, and away to the right of that again was a tall minaret and a dome, locally said to be the mausoleum of Ayaz the slave and minister of Mahmud of Ghazni, whose native place it was. The Tarikh-i-Yamini, however, states that the founder of the robat at Sangbast was Arsalan Jazib, Wali of Tus under Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (997-1028), whose mausoleum was also there. The probability, therefore, is that these are the remains of those buildings.

Later, Sir Percy Sykes visited the site in 1905 and gave a short description as follows (Sykes, “The Fifth Journey,” p. 577):

The interest of Sangbast centres in a ruined dome and a lofty column, both built of burnt brick. Round the top of the latter, which is in an almost perfect state of preservation, is a Kufic inscription, which was photographed. Eiaz, the vizier of Mahmud of Ghazni, who was contemporary with Alfred the Great, founded these buildings as a college and tomb for a saint named Mirza Abdul Kasim, his religious leader. Until the last generation, there were two of these columns.

Ernst Diez, who studied the ruins in 1913, best describes the standing structures and the nearby caravanserai. Diez’s publication remained the major source of studies for a long time in the absence of any further archaeological exploration of the site.

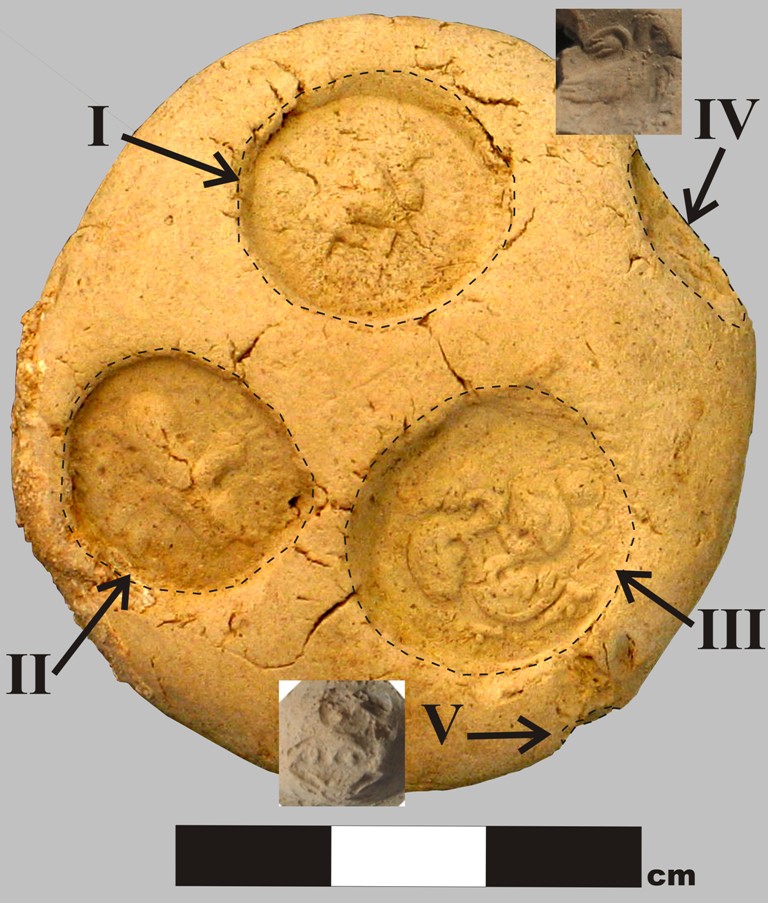

In 1973, Yaqub Daneshdoust and Hasan Rayati undertook emergency restoration work on the mausoleum and the minaret under the auspices of the Iranian National Office for the Restoration of Historical Monuments. In the late 1970s, Swiss photographer Georg Gerster captured the first color aerial views of the ruins. In 1978, French art historians Dominique and Janine Sourdel carried out a preliminary study of the inscriptions on behalf of the French National Center for Scientific Research. In 1999, Hossein Abbaszadeh, on behalf of the Khorasan Cultural Heritage Organization, conducted the first-ever preliminary archaeological survey aimed at delineating the boundaries of the historical city of Sangbast. This survey resulted in the discovery of two historical cemeteries located near the wall of the present-day Sangbast factory. Subsequently, the site became the focus of a master’s thesis research project conducted by Najmeh Mousa Tabar and Ahmad Salehi Kakhki. Additionally, a team of archaeologists, including Mohammad Mortezaie, Hossein Abbaszadeh, and Hayedeh Khamseh, carried out excavations in the mosque area. These efforts were undertaken on behalf of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research in collaboration with the University of Tehran.

Bibliography

Abbaszadeh, H., H. Khamseh, and M. Mortezaie, “Masjed-e tarikhi-ye Sangbast,” Faslnāme-ye Pazhuheshhā-ye Bāstānshenāsi-ye Iran, vol. 31, 1400/2021, pp. 289-306.

Diez, E., Die churasanische Baudenkmäler, pp. 52-55.

Manini, Ahmad ibn Ali, Sharḥ al-Yamīnī al-musamma bi-al-Fatḥ al-Wahbī ʻalá Tārīkh Abī Naṣr al-ʻUtbī, vol. 2, 1869, pp. 311-312.

Mousavi, A., “Bricks, Tiles and Domes: Sites and Monuments Dating from after AD 651,” in Ancient Iran from the Air, edited by D. Stronach and A. Mousavi, photographs by G. Gerster, Mainz, pp. 120-122, plates. 71 and 72.

Salehi Kakhki, A. and N. Mousatabar, “Pazhuheshi bar shenākht-e majmu’e-ye Arsalan Jazib dar dore-ye Ghaznavi dar Sangbast,” Pazhuheshhā-ye Tārikhi, Faculty of Letters and Humanities, University of Isfahan, vol. 16, 1391/2012, pp. 103-120.

Salehi Kakhki, A. and N. Mousatabar, “Bāznegari-ye plan va taz’ināt-e maqbare-ye Arsalan Jazib va Mil-e Ayaz dar dore-ye Ghaznavi,” Faslnāme-ye Honar va Tammadon-e Sharq, vol. 3, No. 9, 1394/2015, pp. 11-24.

Schroeder, E., “The Seljuk Period”, in A Survey of Persian Art, edited by Arthur Upham Pope and Phyllis Ackerman, vol. 3, Architecture, Its Ornament, City Plans, Gardens, 2nd ed., Tokyo, 1964, pp. 986-988.

Seyf al-Dowleh, Sultan Mohammad, Safarnameh, edited by A. Khodaparast, Tehran, 1364/1985.

Sourdel, D. and J. Sourdel-Thomine, “A propos des monuments de Sangbast,” Iran, vol. 17, 1979, pp. 109-114.

Sykes, P. M., “A Fifth Journey in Persia (Continued),” The Geographical Journal, vol. 28, No. 6, Dec. 1906, p. 577.

Yates, Ch. E., Khurasan and Sistan, London, 1900, p. 39.

Utbi, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Jabbar, The Kitabi-i-Yamini, historical memoirs of the Amír Sabaktagín, and the Sultán Mahmúd of Ghazna, early conquerors of Hindustan, and founders of the Ghaznavide dynasty, translated from the Persian version of the contemporary Arabic chronicle of al-Utbi, by James Reynolds, London, 1853.