Kashmar Towerبرج کاشمر

Location: The Kāshmar tower is located 40 km west of Kashmar, in northeastern Iran, Razavi Khorasan Province.

35°17’31.0″N 58°06’11.3″E

Historical Period

Islamic

History and description

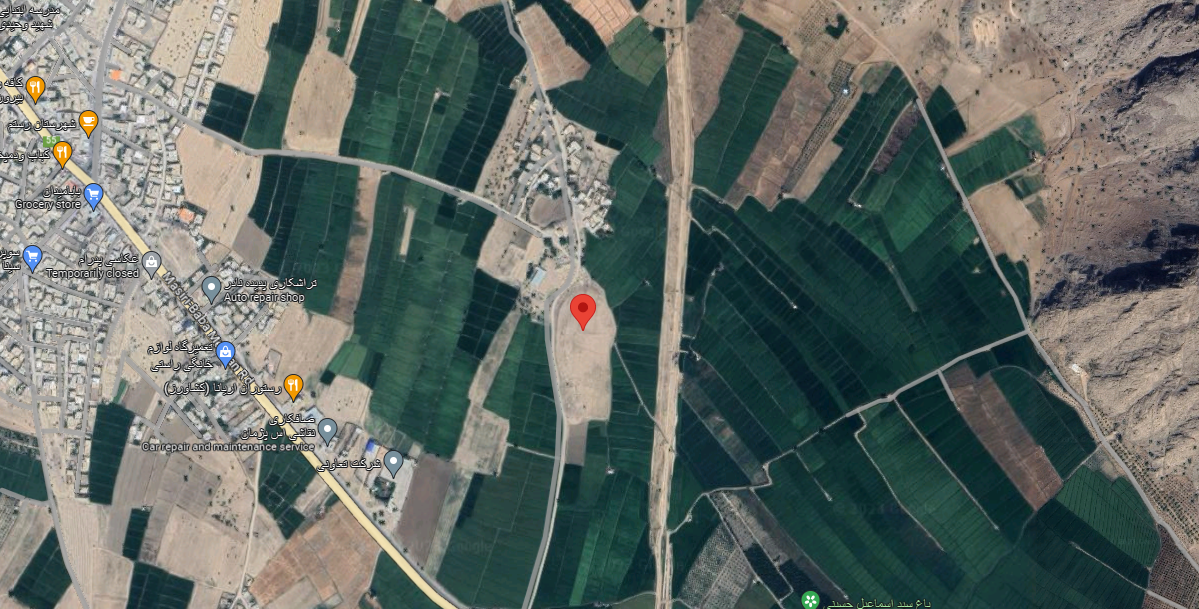

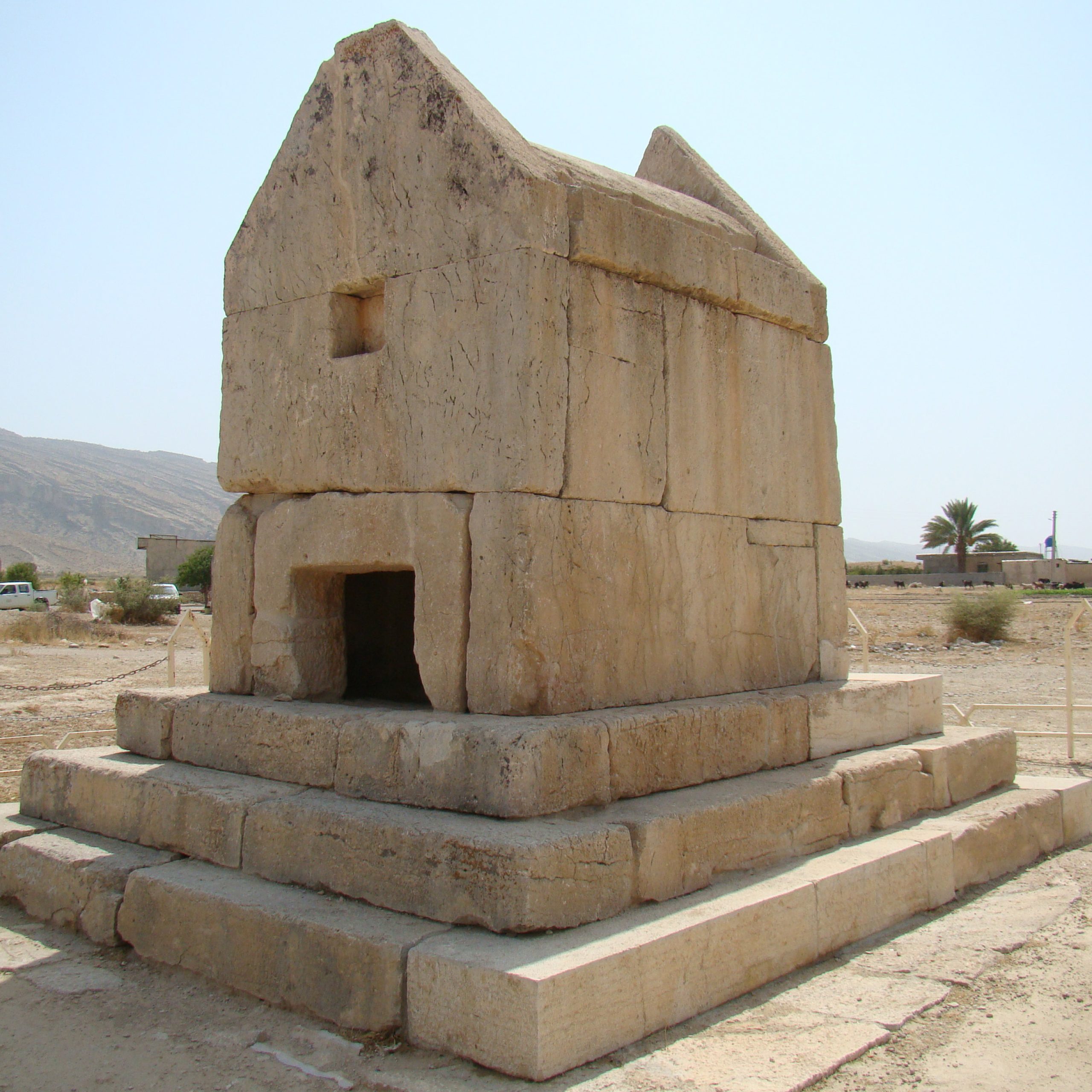

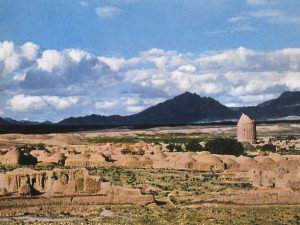

The Kāshmar tower is located in the village of Aliābād (fig. 1), 40 km west of Kāshmar, and is visible from 5 kilometers north of the Bardeskan–Kāshmar road. It stands atop the remnants of an old fortress known as Kooshk. Likely serving as a tomb, the structure is also called the Kāshmar tomb tower.

Kāshmar is often identified with the old Torshiz, the foundation of which is attributed to the legendary King Gūshtāsp, son of Lōhrāsb. Hamdollah Mostowfi, while describing old Torshiz, refers to Kāshmar and its famous tree in his Nuzhat al-Qolūb (Hamdollah Mostowfi, The Geographical Part of Nuzhat al-Qolūb, p. 142):

Kashmar is a provincial town of this district, and here, of old, was a cypress tree, taller than any other in all the rest of the world. It was planted, it is said, by Jamasp the Wise, and more than once in the Shah Namah, the Cypress of Kashmar is mentioned, as for instance in the couplet:

And a branch of cypress from Paradise, they brought

Which he planted before the gate of Kashmar

According to Abolfazl Beyhaghi, the renowned eleventh-century historian, drawing on the accounts of Tha‘ālibī of Nishapur, Gōshtāsp, after converting to the Zoroastrian faith, ordered the planting of this cypress tree. Centuries later, Caliph al-Mutawakkil commanded it be cut down and transported to Baghdad for use in the construction of Ja‘fariyya. However, when the Kāshmar Cypress reached a stage one day’s journey from Ja‘fariyya, al-Mutawakkil’s servants assassinated him in December 861 A.D., and he never got to see the tree. The “Kāshmar Cypress was 1,405 years old at the time it was cut down.” In 1272, Marco Polo, while traveling past Kāshmar on his way to China, was told that this was the “region of the cypress tree.” The legend has since been found credible among scholars of ancient Iran. Avraham Valentine Williams Jackson, in his biography of Zarathustra, writes (Jackson, Zoroaster, p. 80):

In telling the story of Zoroaster and of Vishtaspa’s embracing the new Faith, the Shah Namah narrates how Zardusht planted a cypress-tree before the door of the fire-temple at Kishmar, in the district of Tarshiz in Khorassan or Bactria, as a memento of Vistaspa’s conversion, and had inscribed upon its trunk that ‘Gushtasp had accepted the Good Religion.’! Marvellous became the growth and age of this wonderful tree, the famous cypress of Kishmar (sarv-e Kishmar), as recounted by the Farhang-i Jahangiri, Dabistan, and other writings, …

A similar account is given by Herzfeld, who discusses the date when the cypress tree was cut to be transported to Baghdad, and compares it with similar foundations (Herzfeld, Zoroaster and His World, pp. 37-38):

This was a temple like the one in which the cypress was planted. Kishmar lies close enough to Tōsa, the residence of Vištaspa, for them to be regarded as the same. But the legends of the great “ataxš e Varhrān or dynastic fires” viz. the azar xvarah or fernabag on the rozita mountain, or the āzar burzēmihr of Rēvand, both quite near Tōsa and Nīshāpūr, ascribe their foundation likewise to Višaspa, and just as Shāhpuhr founded five, the grand vizier Mihrnarseh three fires ⸺among them a “fire of the cypress, sarwistān”⸺ Vištaspa may have founded more than one fire at the same time. Firdausi identifies the Burzēnmihr fire with that of Kishmar.

Today, old cypresses are found in Khorāsān, in places such as Forg, Birjand, and Qāen. The presence of old trees strongly supports the reliability of the tradition. Walther Hinz places the planting of the Kāshmar cypress by Zarathustra in front of the fire sanctuary in the year 588 B.C.

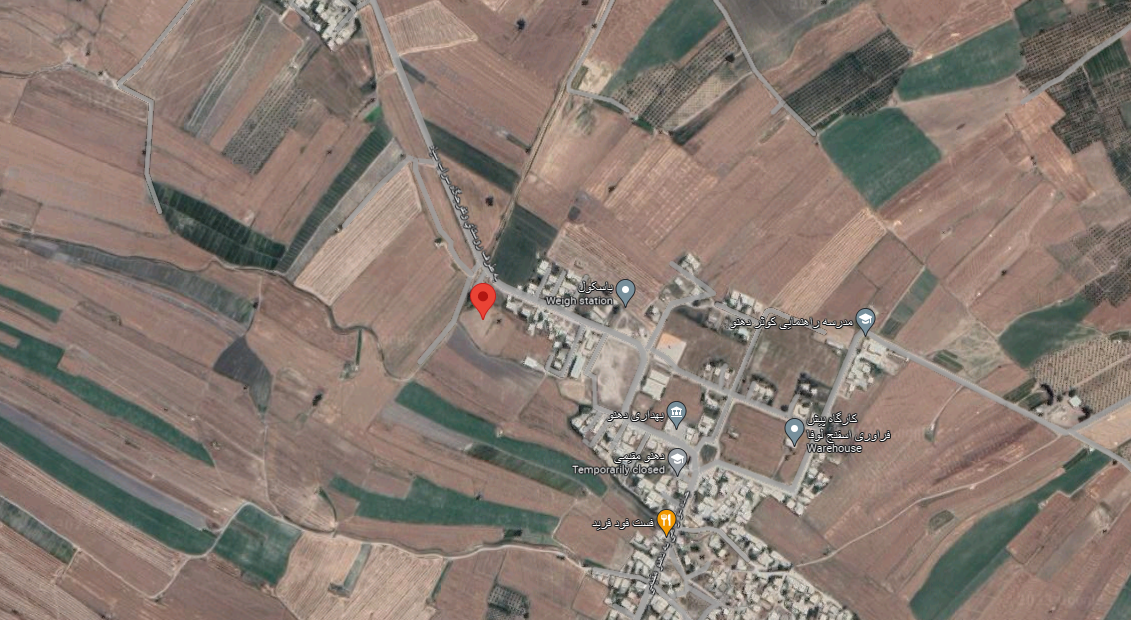

The tower stands 18 m. tall, with an exterior circumference of 42 m. and an interior circumference of 21 m (fig. 2). Its exterior features a conical brick covering, and the structure itself is double-layered: in addition to the outer conical roof, there is an inner, dome-shaped ceiling resembling a skullcap. The outer shell rises significantly higher—about 5 m. taller than the inner shell. A spiral staircase with approximately 50 steps winds between the two walls, leading up to the inner shell of the dome.

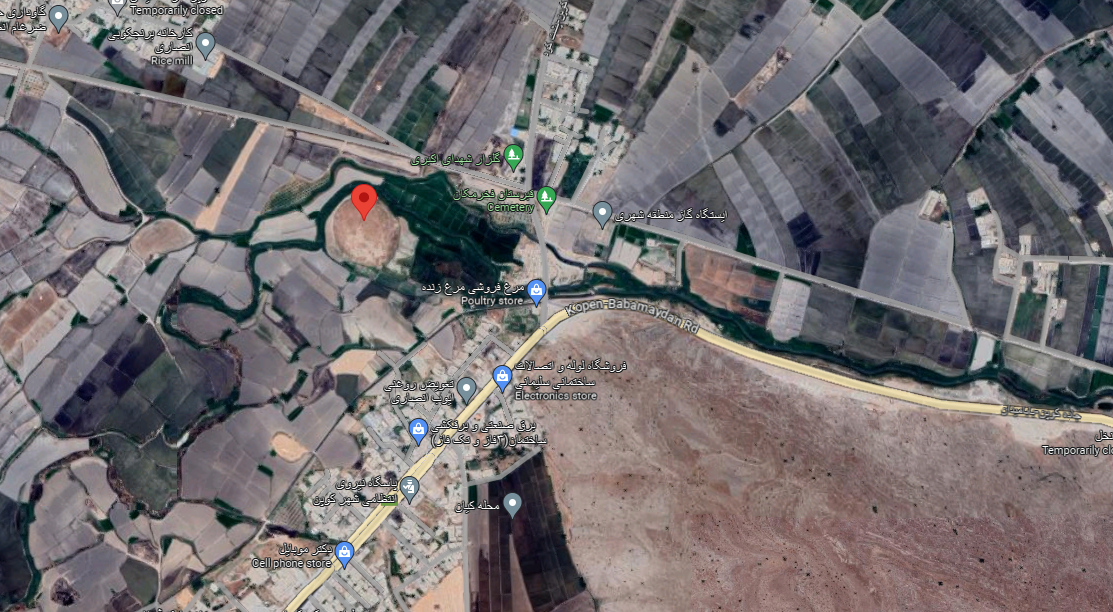

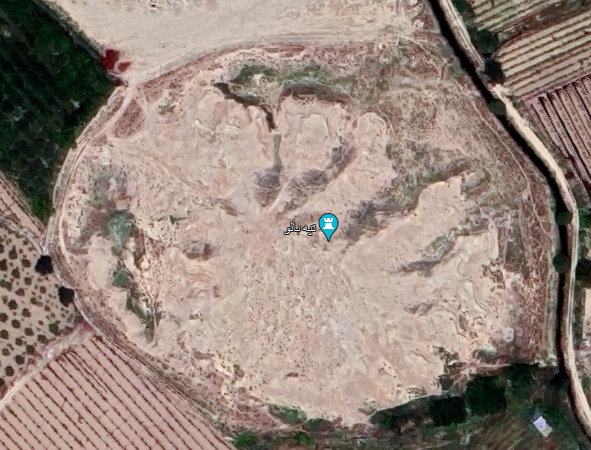

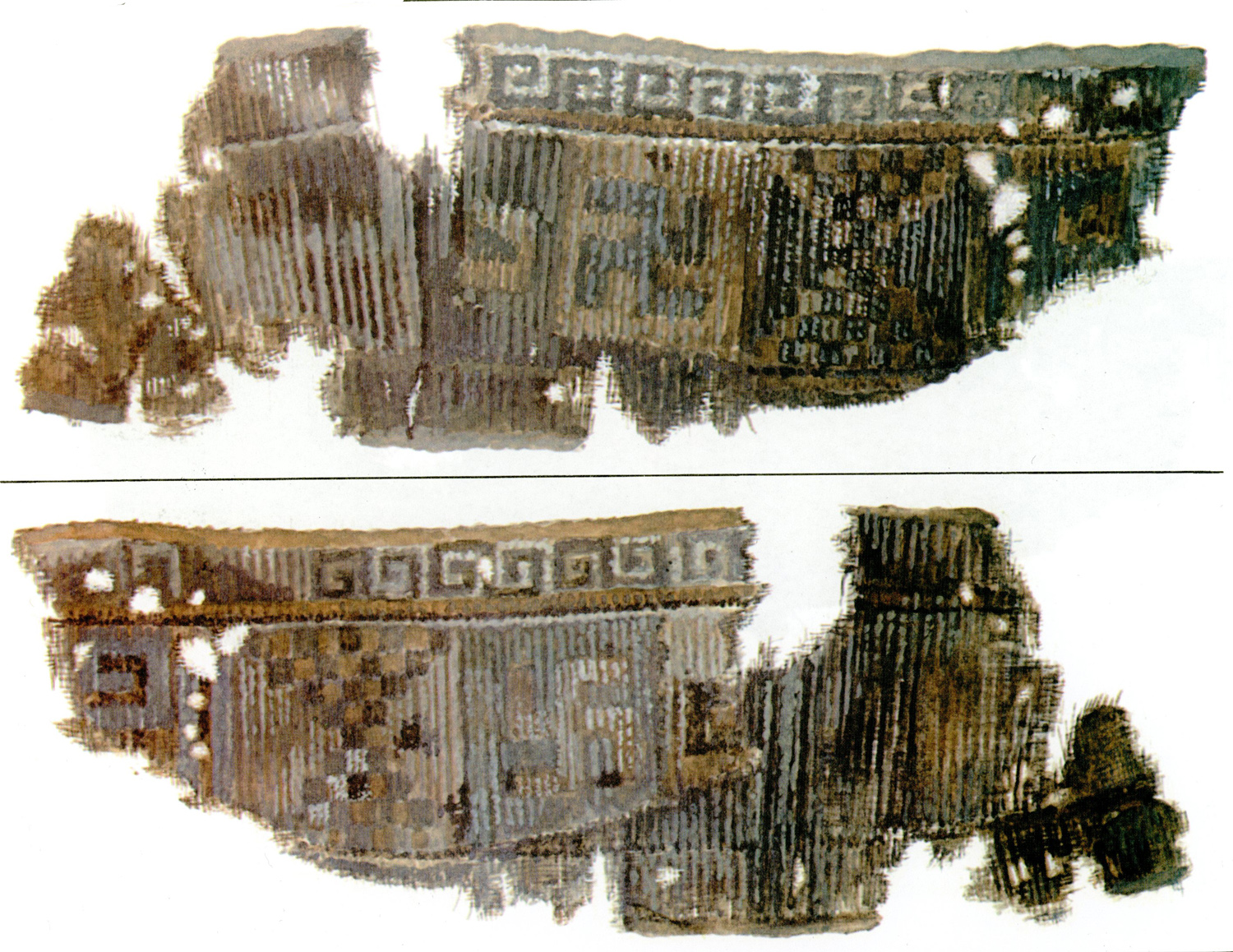

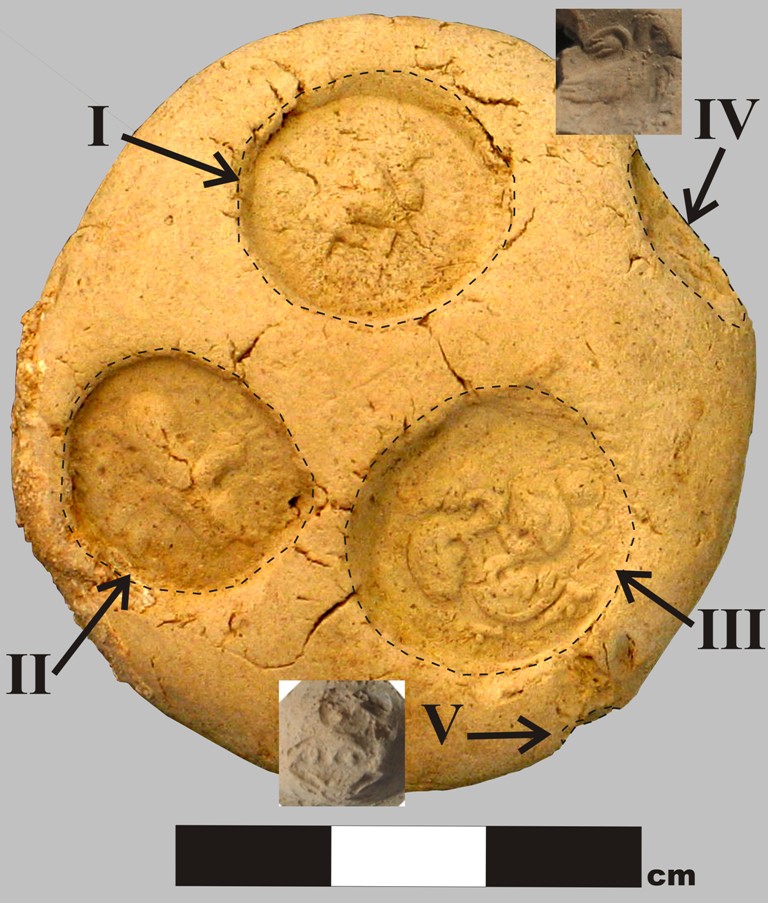

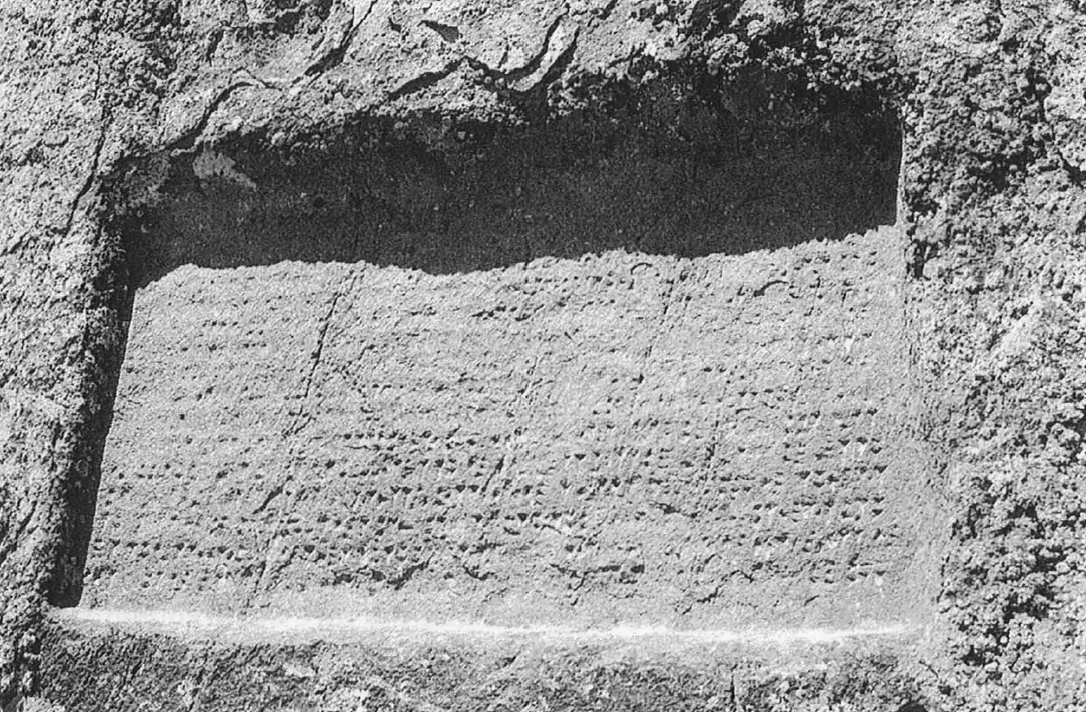

The building’s body consists of two sections: the lower section is dodecagonal, forming the foundation, while the upper section has 48 half-column flutes (fig. 3). There are also twelve diamond-shaped brick frames, adorned with geometric patterns of brick and turquoise-colored tiles that enhance their appearance. A largely destroyed and fragmented inscription, naming the monument’s builder, is placed below the dome. Openings are built into the tower’s walls for interior lighting. The interior of the building (fig. 4) has three levels, with the peak of the main dome reaching 31 meters above the floor. Its architecture resembles the Rādkan tower style, though no inscription remains except evidence that there was one at the entrance. This tower was built in the architectural style of the late 7th century AH, close to the Seljuk period.

Max van Berchem writes that the style of the lettering and the accompanying arabesque ornamentation suggest a date in the first half of the 7th century A.H./13th century A.D. Accordingly, the Kāshmar tower —whose builder remains unknown due to the absence of additional inscriptions— can be placed in roughly the same period as the Rādkān tower. The two structures share a remarkable resemblance in their overall form and articulation, including their profiles and the decorative treatment of the engaged columns on the cylindrical shaft. The Rādkān tomb tower seems to have served as a model for the Kāshmar tower. Judging by its style, this structure must be even later than the Mil-e Rādkān and therefore cannot be dated earlier than 700 H./ 1300 A.D.

Fig. 1. The Kāshmar tower in the village of Aliābād in the late 1950s (image: after Hinz, Zarathustra, color photograph)

Fig. 2. The Kāshmar tower (image: Creative Commons)

Fig. 3. The Kāshmar tower. Close-up of the fluted columns (image: Creative Commons)

Fig. 4. The Kāshmar tower. View of the interior and cupola (image: Creative Commons)

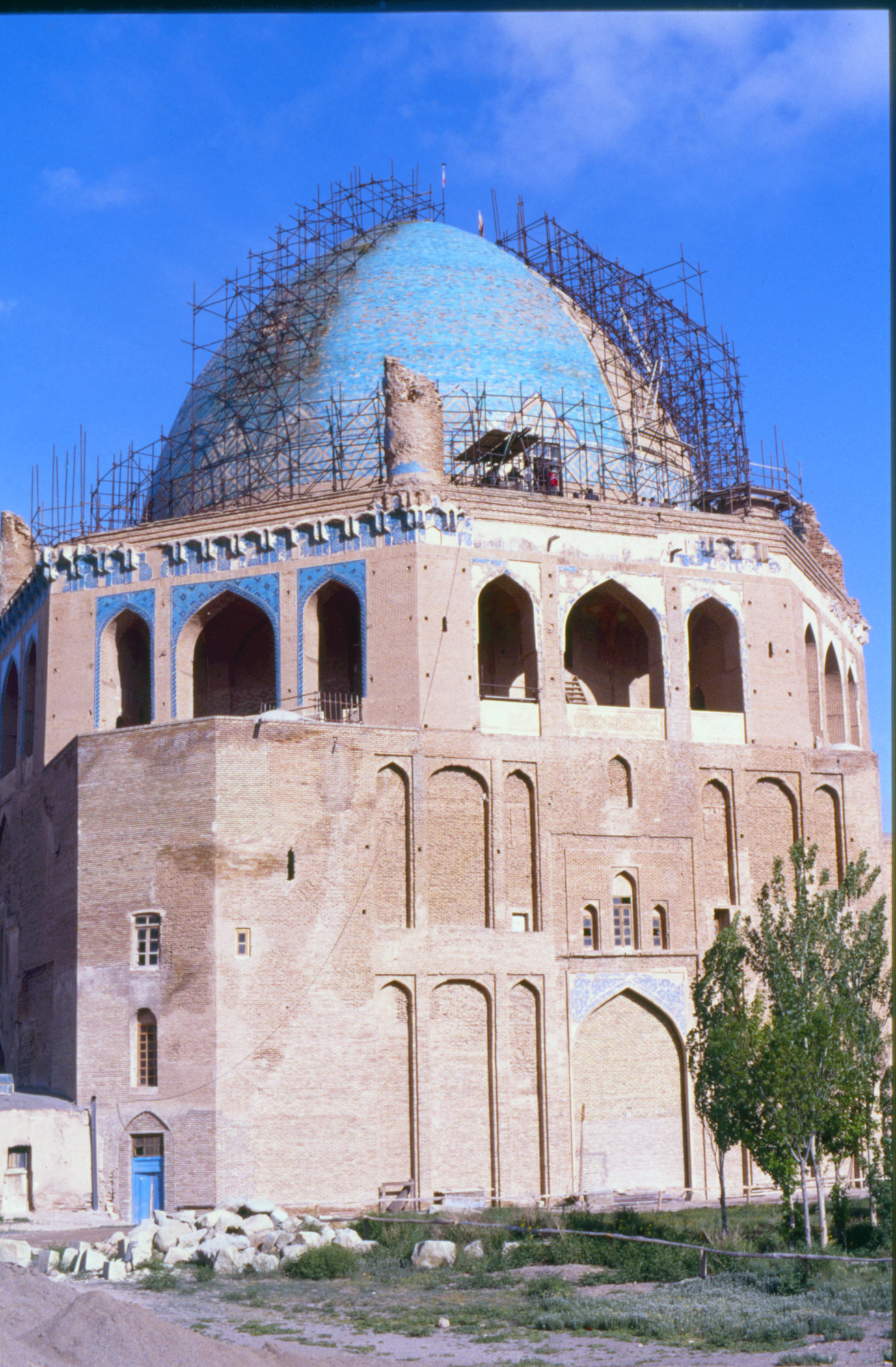

Archaeological Exploration

Due to Kāshmar’s location, set apart from the main Khorasan route leading to Mashhad, the tomb tower drew relatively little attention from travelers and visitors in the nineteenth century. In 1908, Major Percy Sykes (later Sir Percy Sykes) visited the monument and noted the presence of blue enameled bricks on the Kāshmar tower, which are characteristic of the 13th-century Mil-i Radkān. The only thorough study of the tomb-tower at Kāshmar is the one by Ernst Diez and Max van Berchem (for the fragmented inscription) in 1911. Before World War I, Henry Viollet took photographs of the monument (fig. 5). Ernst Herzfeld believed that the tomb tower is slightly later in date than that of Mil-e Rādkān near Qūchān, that is, after 680 A.H. /1281 A.D. Donald Wilber, without seeing the monument, agrees with Herzfeld’s dating. Following Syke’s observations of glazed terracotta in dark and light blue, Wilber compares the tower at Kāshmar with the mausoleum of Öljeitü at Soltāniyeh. The monument was the object of a serious restoration work and conservation project in the 1970s on behalf of the Iranian Office of Preservation and Conservation of Historical Monuments.

Bibliography

Beyhaqi, A., Tarikh-e Beyhaq, edited by A. Bahmanyar, Tehran, 1317/1938, p. 281.

Diez, E., Die Churasaniche Baudenmäler, Berlin, 1911, pp. 46-47, 109-110, pls. 6/2 and 9.

Hamdollah Mostowfi, The Geographical Part of The Nuzhat-al-qulub, by Hamd-allah Mustawfi of Qazwin in 740 (1340), translated by G. Le Strange, London, 1919, p. 142.

Herzfeld, E, Zoroaster and his World, vol. 1, London, 1947, pp. 19-20, 37-38.

Hinz, W., Zarathustra, Stuttgart, 1961, pp. 22-24.

Jackson, A. V. Williams, Zoroaster, the Prophet of Ancient Iran, New York, 1899, p. 80.

Sykes, P. M., “The Sixth Journey in Persia,” The Geographical Journal, vol. 37, No. 2, February 1911, p. 160.

Wilber, D. N., The Architecture of Islamic Iran: The Il Khanid Period, New York, 1969, pp. 120-121.