Arg-e Bamارگ بم

Location: Arg-e Bam is located 200 km southeast of Kerman, in southeastern Iran, Kerman Province.

29°06’51.2″N 58°22’06.8″E

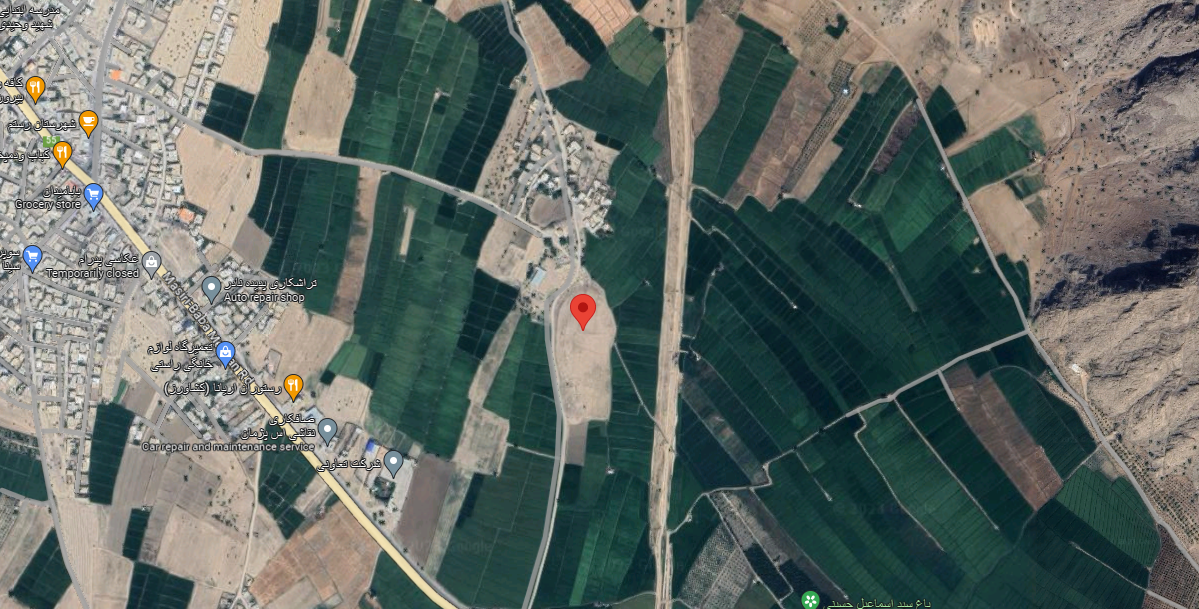

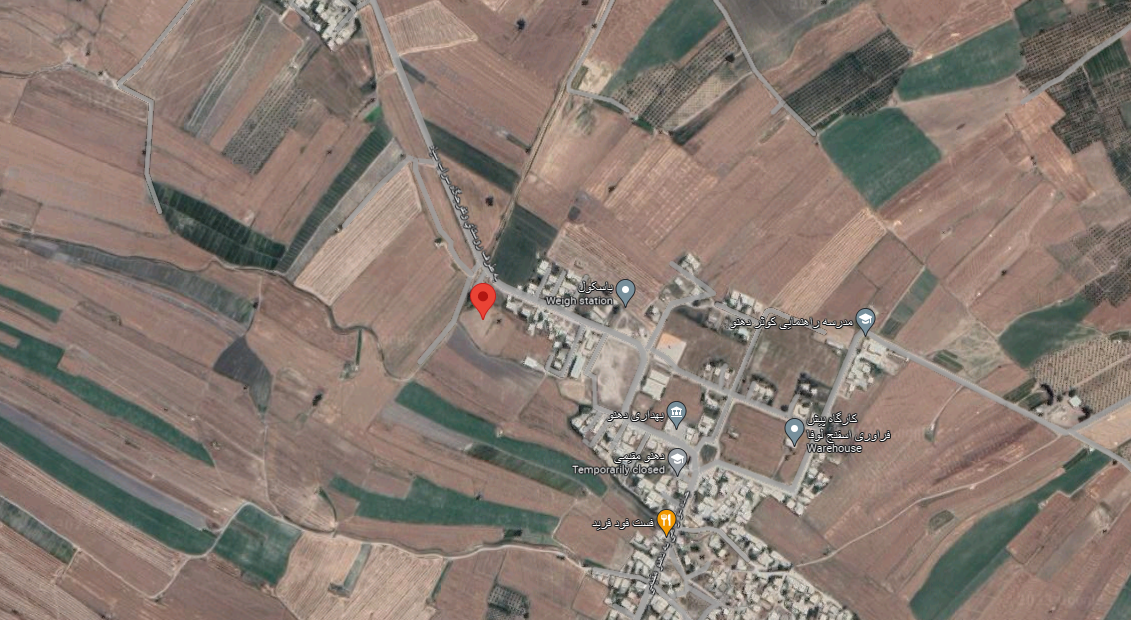

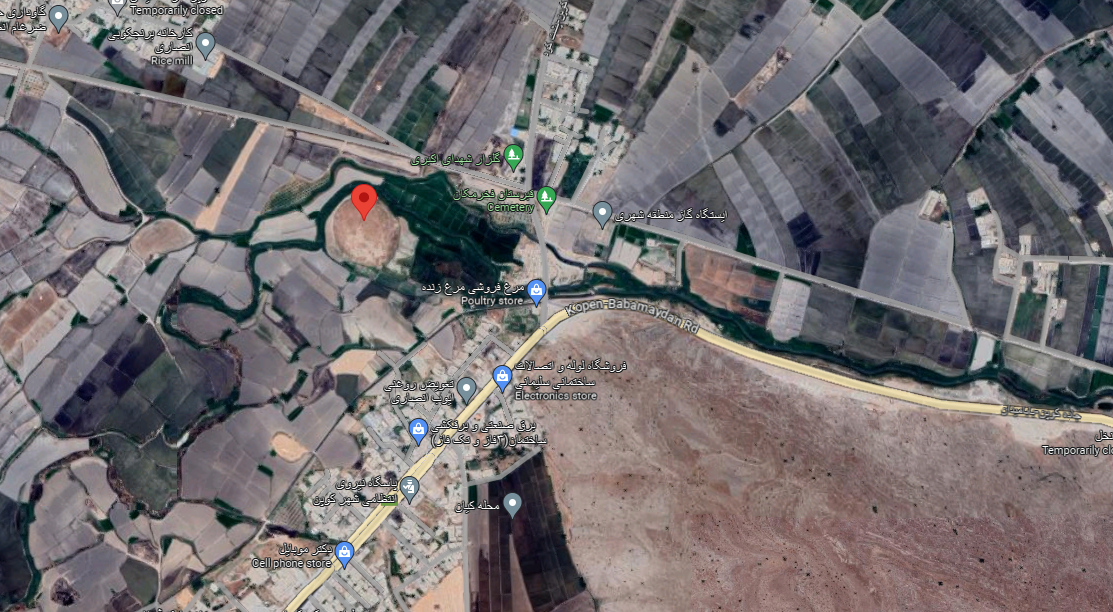

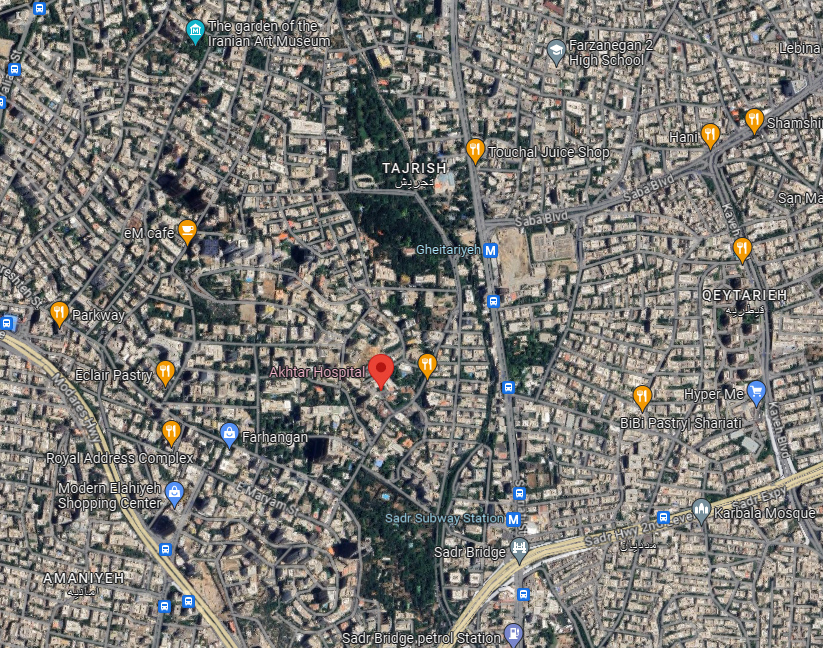

Map

Achaemenid, Sasanian, Islamic

History and description

Arg-e Bam or the Bam Citadel is situated in a desert environment on the southern edge of the Iranian Plateau. Bam is located 200 kilometers southeast of Kerman along the road that connects Kerman to Iranshahr on the Oman Sea. It lies only 120 kilometers north of Jiroft, renowned for its recent and noteworthy archaeological discoveries.

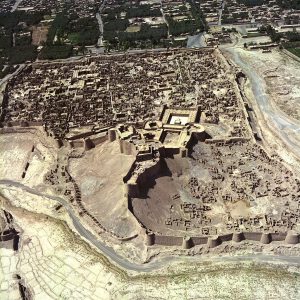

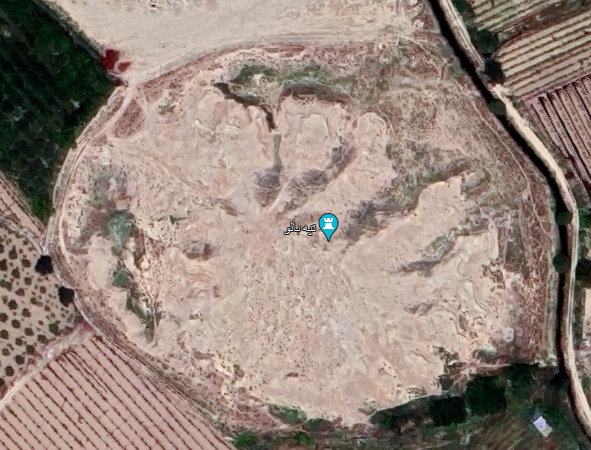

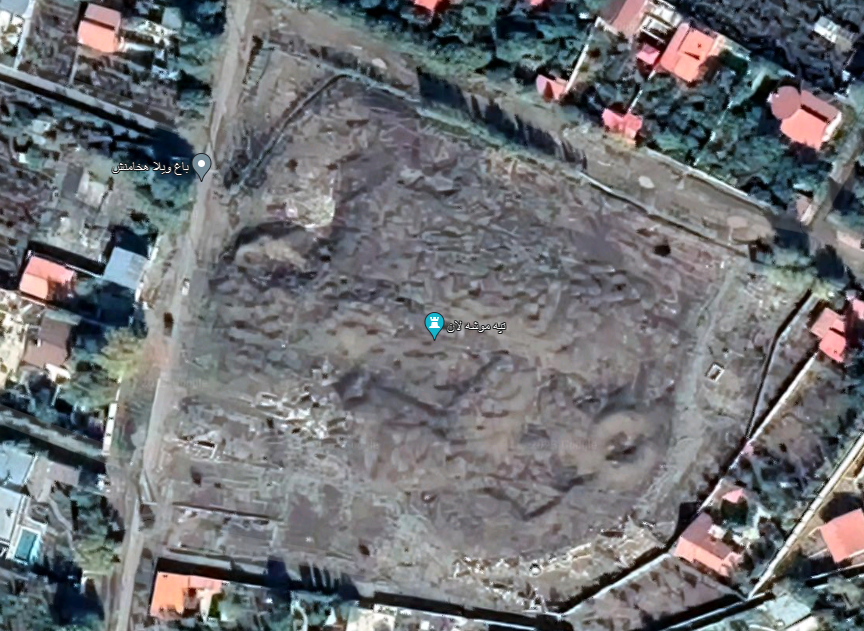

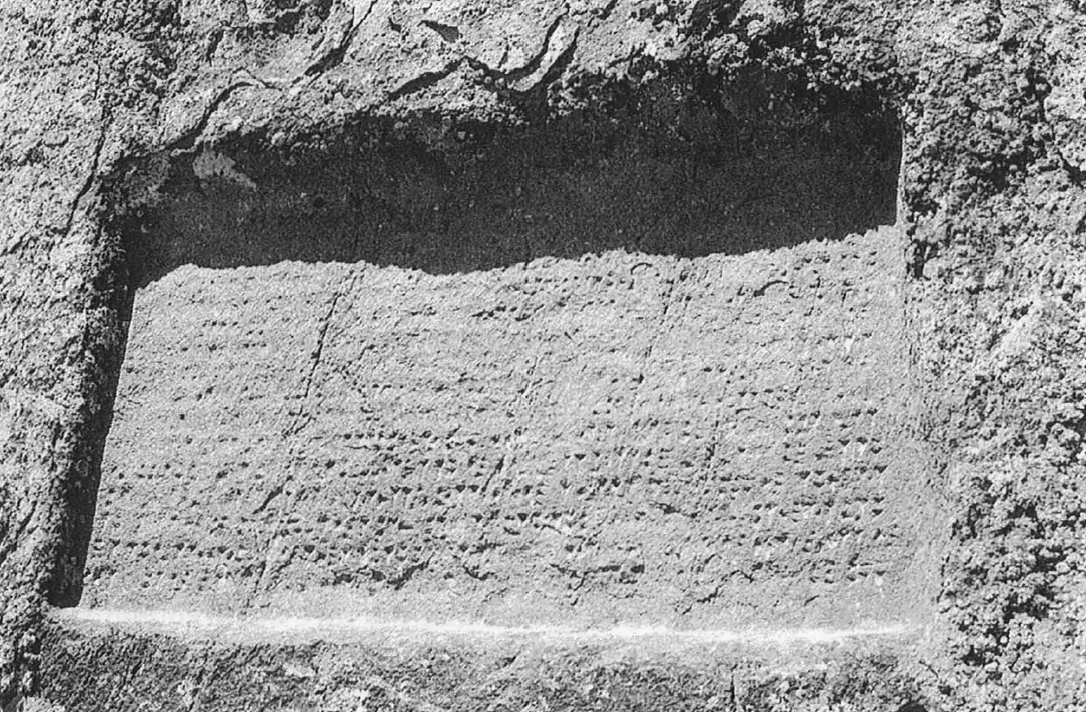

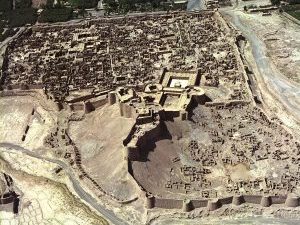

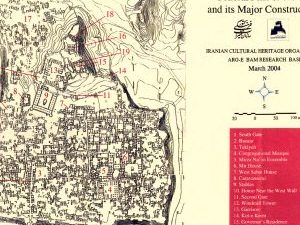

The fortified town was built on a natural rock, rising 45 meters above the surrounding area (fig. 1). The core of the layout of the town forms a rough rectangle, measuring approximately 430 meters in the south, about 390 meters in the north and northeast, 280 meters in the east, and 540 meters in the west, corresponding to the fortified enclosure with 38 watchtowers. To the north lies the Citadel, with its main gate located in the south. Additional gates include Kot-e Kerm (the Worm’s Gate), Shāhneshin, Qūrkhāneh, and Qolāmkhāneh. Surrounding the fortified enclosure is a moat spanning 10 to 15 meters in width.

An expansive icehouse is just outside the city wall, in the northeast of the Citadel. Additionally, a sizable watchtower stands on a rocky hill north of the current enclosure, connected to the old town wall through a narrow fortified corridor.

The town has two distinct areas (fig. 2): the citadel or the arg and the lower town. The Citadel, often referred to as Hākemneshin or Governor’s Quarter, is characterized by a complex organization, including eight structures. Among them are two structures enclosed by fortified walls, taking the form of two terraces in the southeastern part. The highest part of the Citadel is occupied by the Governor’s Residence and the Chāhārfasl Kiosk. The Governor’s Residence features a central courtyard with two eyvāns and rooms. This was the place where the English traveler Henry Pottinger was received in 1818. Subsequently, in the same location, Sir Percy Sykes, the indefatigable British agent in southeastern Persia, visited the governor of Bam in 1896. He provided a vivid description of the town and the Citadel as follows:

“From the roof of the building, we enjoyed a wonderful view. Looking back, Kuh-i-Hezar with its mantle of freshly fallen snow riveted our gaze, and on each side of the valley, the hills showed up against the turquoise sky, the Shah Sowaran range to the south forming another vision of beauty. Below us lay the date groves of Bam, and we could trace its river to the northeast; we also indistinctly saw the greenery of Narmashir.”

A four-side watchtower lies to the north side of the Governor’s Residence. It has been suggested that the tower served the purpose of transmitting signals using fire at night and smoke during the day to communicate with the surrounding countryside. As a result, it acquired the name “Fire Tower” (Atash-Khāneh).

The Governor’s Residence is equipped with a bathhouse and wells are located at the extreme north end of the rocky summit of the Citadel. On a lower level, there was the Garrison at the north side of the Stables, which was used as storage for artillery in the later periods. The Stables building is associated with the most renowned historical events in Bam. It was within these walls that the capture of Lotf-‘Ali Khān, the final Zand pretender to the Persian throne, occurred in late autumn of 1794. The Zand prince was delivered into the hands of his ruthless adversary, Aghā Mohammad Khān Qajar, who subjected him to torture and eventual death. Three wells on the southeast side of the Garrison provided water for the entire area. There is a second wall that separates the military sector and the residential quarters in the south. Guard rooms and a watchtower are situated on both sides of the entrance in this area.

There is a small caravanserai behind the Stables and includes a courtyard around which rooms were built. At the foot of the Citadel area lies the town itself with mud-brick houses, including a Jewish neighborhood known as the Sābāt-e Johudhā and the West Sābāt House. The latter consists of a relatively large house with a central courtyard flanked by two series of rooms on two floors. The building was one of the town’s prominent constructions severely damaged in the 2003 earthquake. In the heart of the town stood a grand structure known as the Mirzā Na’im architectural complex, commissioned and endowed by Haji Seyyed Mohammad, a prominent figure in Bam, likely towards the end of the Safavid period, c. 18th century. This complex comprised a tekiyeh (religious theater) and a madrasa (religious school). Located nearby was Bam’s congregational mosque, one of the oldest mosques ever constructed in Iran, mentioned the nine-century historian Moqqadasi. On the north side of the building, there existed a mihrab adorned with an inscription dating back to 1160 h./ 1747. The mosque featured a courtyard surrounded by three prayer halls and eyvāns. In the southeastern corner of the mosque, there is a well dug to provide water.

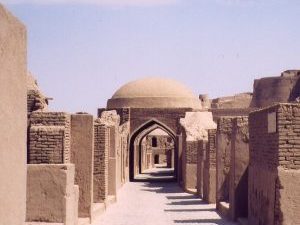

The Bazaar of Bam consists of a line of shops with intersections and paths (fig. 4). Extending from the south Main Gate to the upper part of the Arg, the dimensions of the shops and merchants' compartments vary between the southern and the northern ends within the Citadel. In the middle of the Bazaar, an intersection called Chāhārsūq once had a dome made of mud bricks. The entire alley of the Bazaar was once vaulted, reminiscent of the architectural style seen in other Persian bazaars. The town’s south gate lies at the southern end of the Bazaar’s main axis.

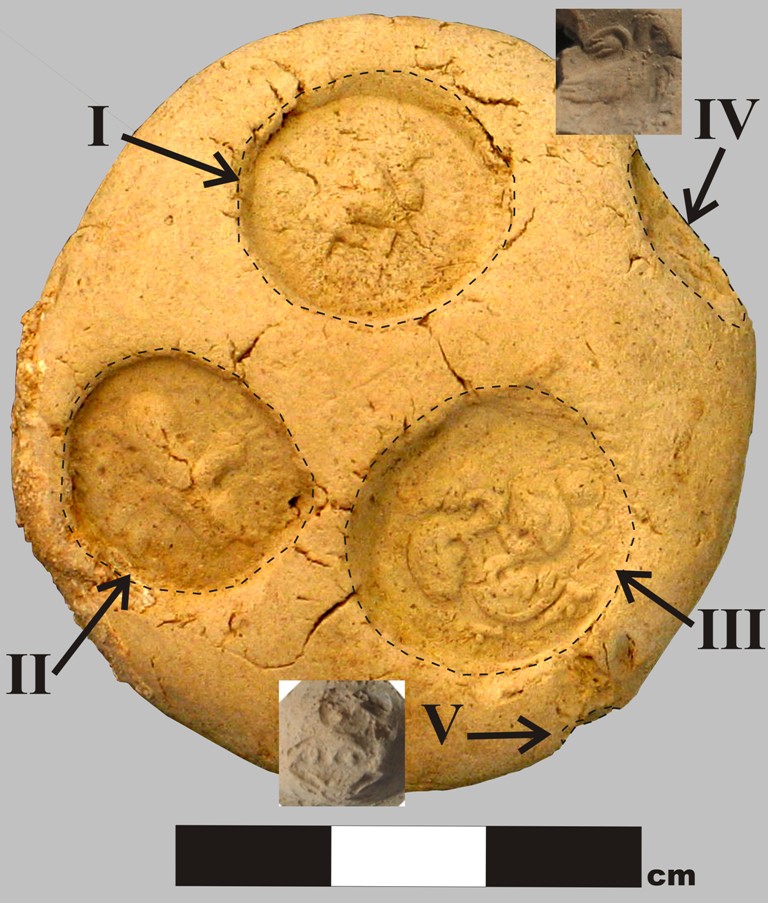

The origins of Bam is said to date to the Achaemenid period (6th to 4th century B.C.). However, given Bam’s strategic situation at the crossroads of significant trade routes and its silk and cotton products, the town’s heyday was between the 7th and the 11th centuries. In the region, life depended on underground irrigation canals known as qanāts, and Bam has preserved some of the earliest quanāts in Iran. Bam’s name is believed to be the ancient term Vahma, signifying prayer and glorification. However, an intriguing ancient folk belief suggests an alternate origin. According to this belief, the town earned its name, Bam, when Haftvad’s mystical Worm exploded, creating a distinctive sound in the 3rd century A.D. The story is related to the rise of Ardashir, the founder of the Sasanian Empire. In Kārnāmeh-ye Ardashir-e Bābakān, a Middle Persian text composed in praise of King Ardashir, it is reported that Ardashir was forced to fight Haftvād. The first historical mention of Bam occurred during the invasion of Iran by Muslim armies in the 7th century. Balāzuri, writing in the 9th century, attributes the conquest of Bam to a certain Mojash’e b. Mas’ud Salami. Tabari's account places this event in the year 30 h./651. Bam had been previously captured by Arab armies, but they were compelled to abandon the town due to a revolt by the local population. Outside the city wall, there are remains of an old mosque, known as the Mosque of Khvārej. According to Ibn Howqal (10th century), there were three mosques in Bam, one belonging to the Khavārej and another to the orthodox Muslims; the third one was situated within the fort. It is plausible that the Mosque of Khavārej and the preserved remains, including the wall, belonged to a single monument. The mud-brick shrine destroyed in the earthquake has been dated back to the late Safavid period and was constructed in mud brick.

The Muslims, led by ‘Abdollāh ibn Amer, achieved the final conquest of Bam in 31/650. Situated approximately 200 meters to the east of the Arg-e Bam, remnants of a shrine attributed to Amer can be found. Adjacent to the Shrine, there was a mosque, of which only a section of its thick wall, measuring 4 meters in height, remained until the earthquake, causing its collapse while leaving its foundations intact. Recent archaeological investigations uncovered traces of an ancient but lesser-known occupation in this area.

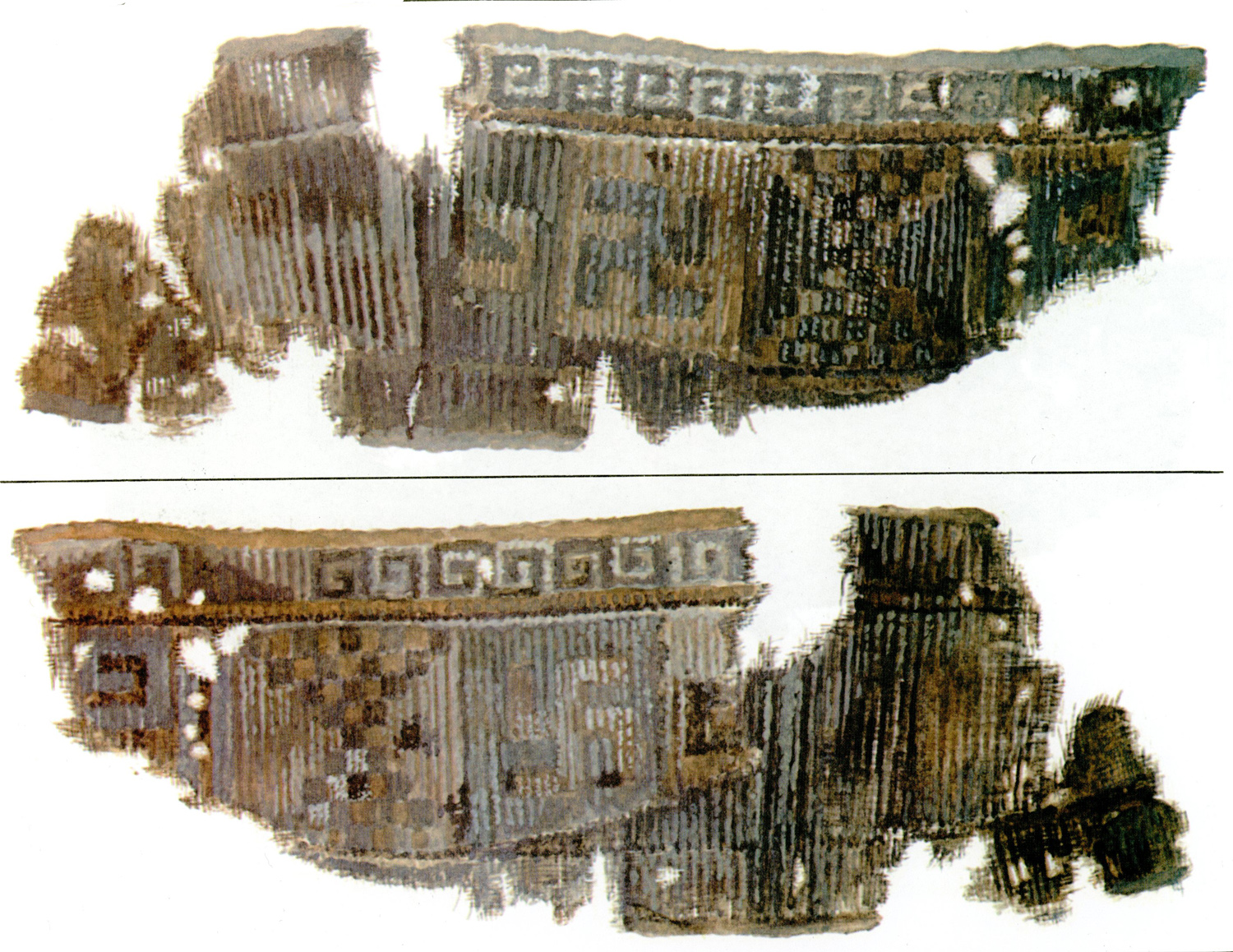

The most detailed description of Bam is left by Moqqadasi who writes that it is an important capital, pleasant and large, and that the inhabitants are skillful and clever. He mentions that “the clothes made here are known in various countries. The city is famous all over the Muslim world, a pride for the country. It is true that the common people here are weavers, and that the water does not taste good, nor is the climate pleasant. The city is fortified and has four gates.” Yāqut, writing in the 13th century, called Bam “an important, noble city, which belonged to the most distinguished cities of Kirman”. On its economic significance, he writes that “the inhabitants are able, most of them are weavers; the gowns from there are famous in all countries. The city has well-stocked bazaars.” During the 11th and 12th centuries, Bam witnessed internal conflicts under the rule of the Saljuqs. The region faced instability and desolation for a prolonged period, spanning thirty-four years until the year 609 h./1213 when entire southeastern Iran fell under the suzerainty of the Malek-e Zuzan. In Bam, the Malek-e Zuzan ordered the demolition of the city walls, aiming to eradicate any plans of insubordination among the local population. Under the Mongol Ilkhans, Bam was in the territory of the Atabeks of Fārs and Kerman who restored Bam's city wall and its citadel.

At the onset of the 15th century, the settlement outside the Citadel was replaced by a new one. A Timurid general seized control of Bam in 811 h./1408-09, and his army encouraged him to restore the Citadel and the town's walls. He complied and directed people to construct houses within the fort, urging them to relocate their residences there.

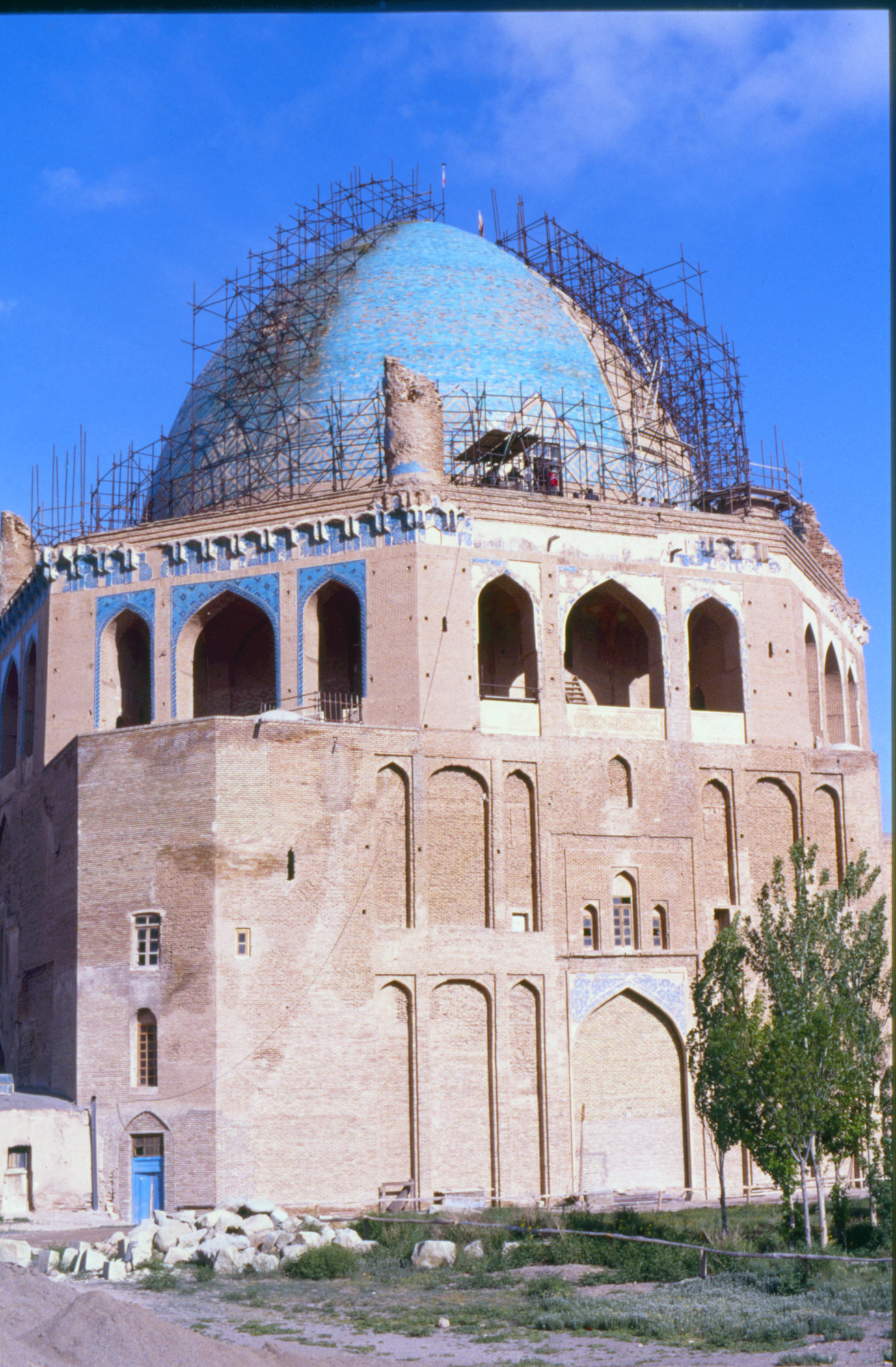

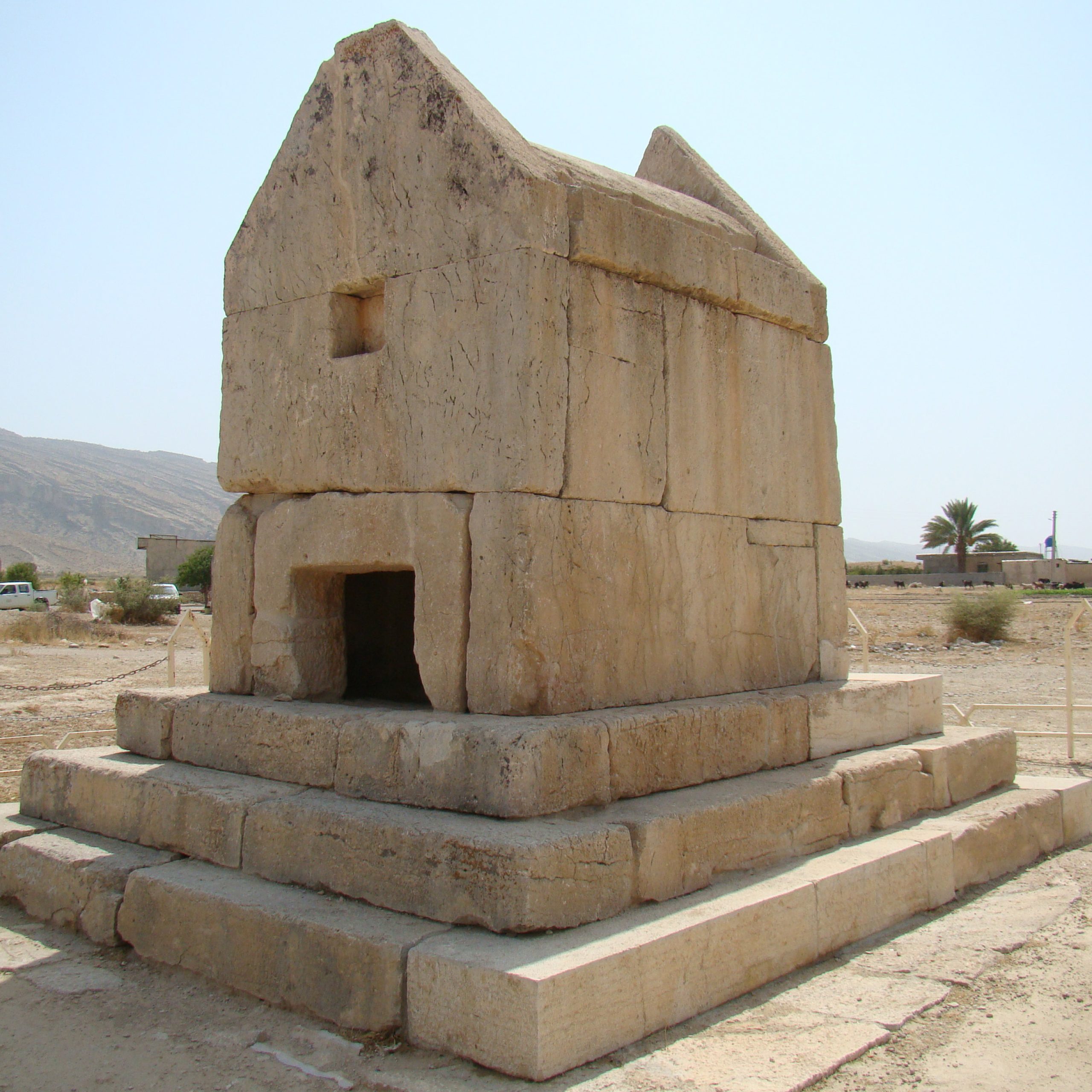

Under the Safavids (1500-1726), Bam served as a military and frontier fortress. Following its occupation by the Afghans, Bam gained strategic significance for the Gelzay tribe, situated in neighboring Narmānshir with the authorization of Nāder Shāh. The Gelzay tribe maintained favorable relations with the Zands, who held power in Shiraz during the second half of the 18th century. This connection likely played a role when Lotf-’Ali Khān, the last of the Zands, sought refuge with the Gelzay tribe after the fall of Kerman in 1794. A year later, the governor of Bam captured Lotf-Ali Khān and handed him over to Aqā Mohammad Khān, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, which ruled Iran until 1926. During the Qajar period, Kerman and Bam experienced a peaceful occupation in 1841 through forged documents orchestrated by Aghā Khān Mahallāti, the head of the Ismaïli sect and a former governor of Kerman. The ensuing unrest in Bam continued until 1855. With the restoration of peace, the town expanded beyond its walls, establishing a new settlement along the river, surrounded by gardens and date groves, approximately 1000 meters southwest of the fort. Bam experienced rapid expansion in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Despite losing its status as the governor's seat of Baluchestān in 1881, the governor, who typically lived in Bampur, favored the milder summer climate of Bam. The commercial activities in the Bazaar were still ongoing until the 1970s. By that time, most of the people had left the walled town to settle in the adjacent areas. Arg-e Bam was severely destroyed by a strong earthquake in 2003 (fig. 3).

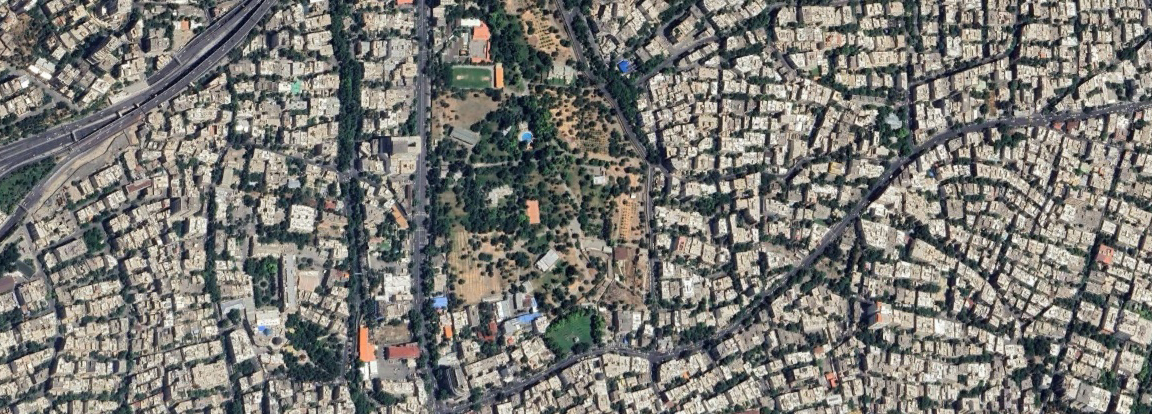

Fig. 1. Aerial view of Arg-e Bam from the north before its destruction in 2003 (image: C. Adle, courtesy of the Bam Research Base)

Fig. 2. General plan of the Arg-e Bam structures (image: C. Adle, courtesy of the Bam Research Base)

Fig. 3. Bam. View of the Upper Town and the Citadel from the Stables after the earthquake, in 2004

Fig. 4. View of the Bazaar before its destruction. The Citadel and its tower can be seen in the background, upper right (image: C. Adle, courtesy of the Bam Research Base)

Archaeological Exploration

In modern times, the English officer and traveler, Henry Pottinger, who passed through Bam in 1810 on his way to India, visited the Citadel and published the first substantial account of Bam in Europe. Then, in 1898, Sir Percy Sykes visited the Citadel and took the first photographs of its mud-brick structures. Following several insurgencies in the middle of the 19th century, Firuz Mirza (then governor of Kerman) led an army and besieged the Citadel. Sykes reported that the town had but 13,000 people and the Citadel was still in use by the governor’s troops. In 1958, the monument was placed on the National List of Historical Monuments of Iran and was protected from further destruction. The whole area of the old town and the Citadel itself underwent careful restorations and maintenance during the past forty years by the Iranian National Office for Conservation and Restoration of Historical Monuments until the massive destruction of the monument caused by the earthquake of December 2003. Bam is on the list of World Heritage Sites in Danger pending achievement of its desired state of conservation by 2010.

Bibliography

Adle, Ch., “Irrigation System in Bam: its birth and evolution from the prehistoric period up to modern times,” In Qanats of Bam, A Multidisciplinary Approach, edited by M. Honari, et al., UNESCO Tehran Cluster Office.

Bastani Parizi, E., “Bam: ii. Ruins of the old town,” Encyclopedia Iranica, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, © Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

De Planhol, X. “Bam: i. History and modern town,” Encyclopedia Iranica, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online, © Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York.

Gaube, H., Bam, Iranian Cities, New York, 1979, chapter 4.

Nurbakhsh, H., Arg-e Bam, typed manuscript, Kerman, 1335 H./1956.

Potinger, H., Travels in Beloochistan and Sinde, 1816, London.

Schwarz, P., Iran im Mittelalter nach den arabischen Geographen, vol. 3, Leipzig, 1912, pp. 236-238, reprinted, Hildsheim – New York, 1969.

Sykes, P. M., Ten Thousand Miles in Persia, 1902, London.